Emotional Demands and Role Ambiguity Influence on Intentions to Quit: Does Trust in Management Matter?

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Does role ambiguity significantly influence employees’ intentions to quit?

- Does role ambiguity increase employees’ emotional demands?

- Do emotional demands mediate the relationship between role ambiguity and turnover intentions?

- Does trust in management moderate the link between role ambiguity and quitting intentions?

- Does trust in management moderate the link between role ambiguity and emotional demands?

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Job Demands-Resources Theory (JD-R Model)

2.2. Conceptual Review and Hypothesis Development

2.2.1. Emotional Demands

2.2.2. Trust in Management

2.2.3. Intentions to Quit

2.2.4. Role Ambiguity and Intentions to Quit

2.2.5. Role Ambiguity and Emotional Demands

2.2.6. The Mediating Role of Emotional Demands

2.2.7. Moderating Role of Trust in Management (TIM)

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sampling Procedure and Characteristics

3.2. Measures and Analytical Technique

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

4.2. Multicollinearity Test and Correlations

4.3. Data Screening

4.4. Assessing the Measurement Model

4.5. Discriminant Validity

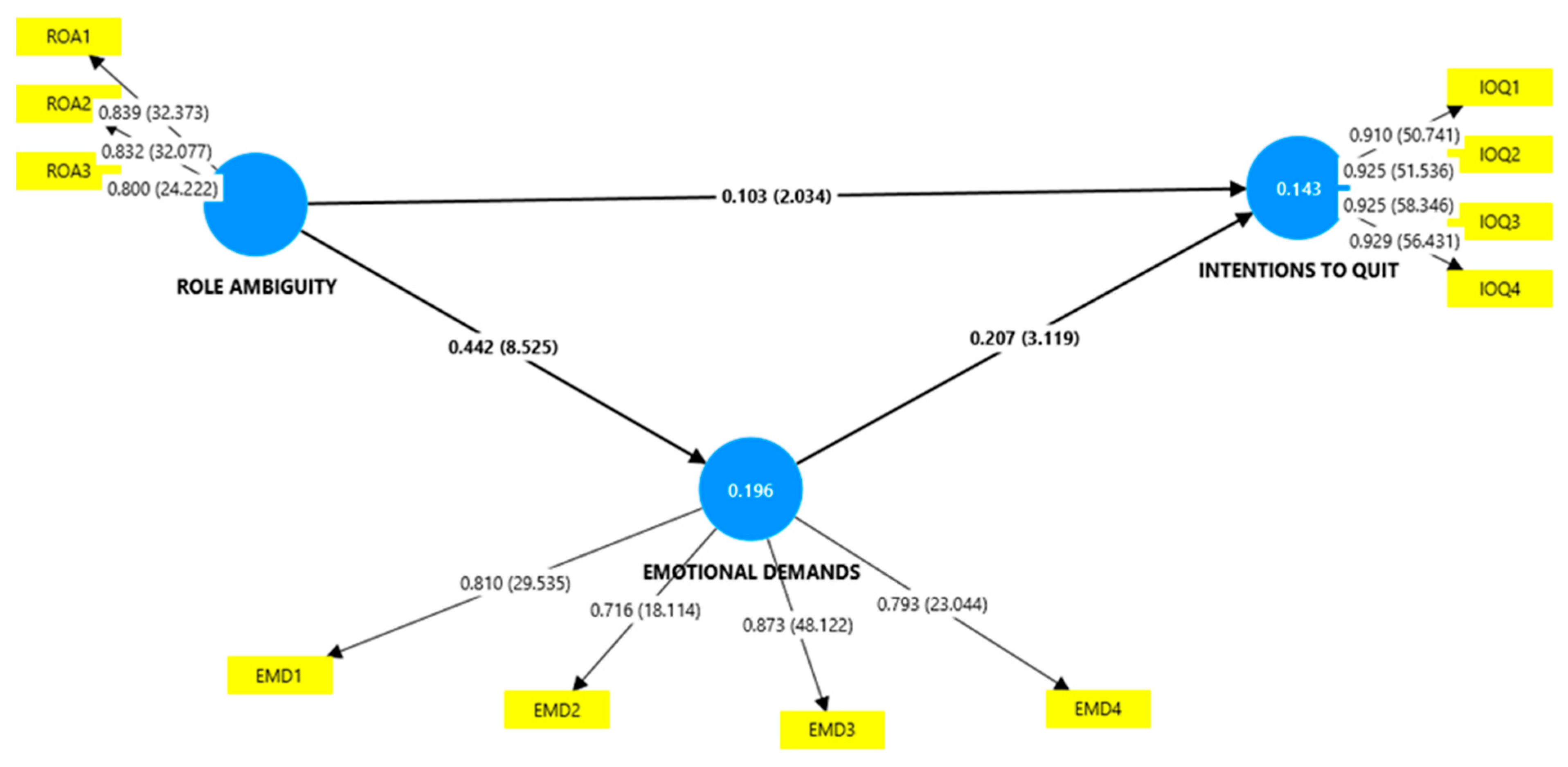

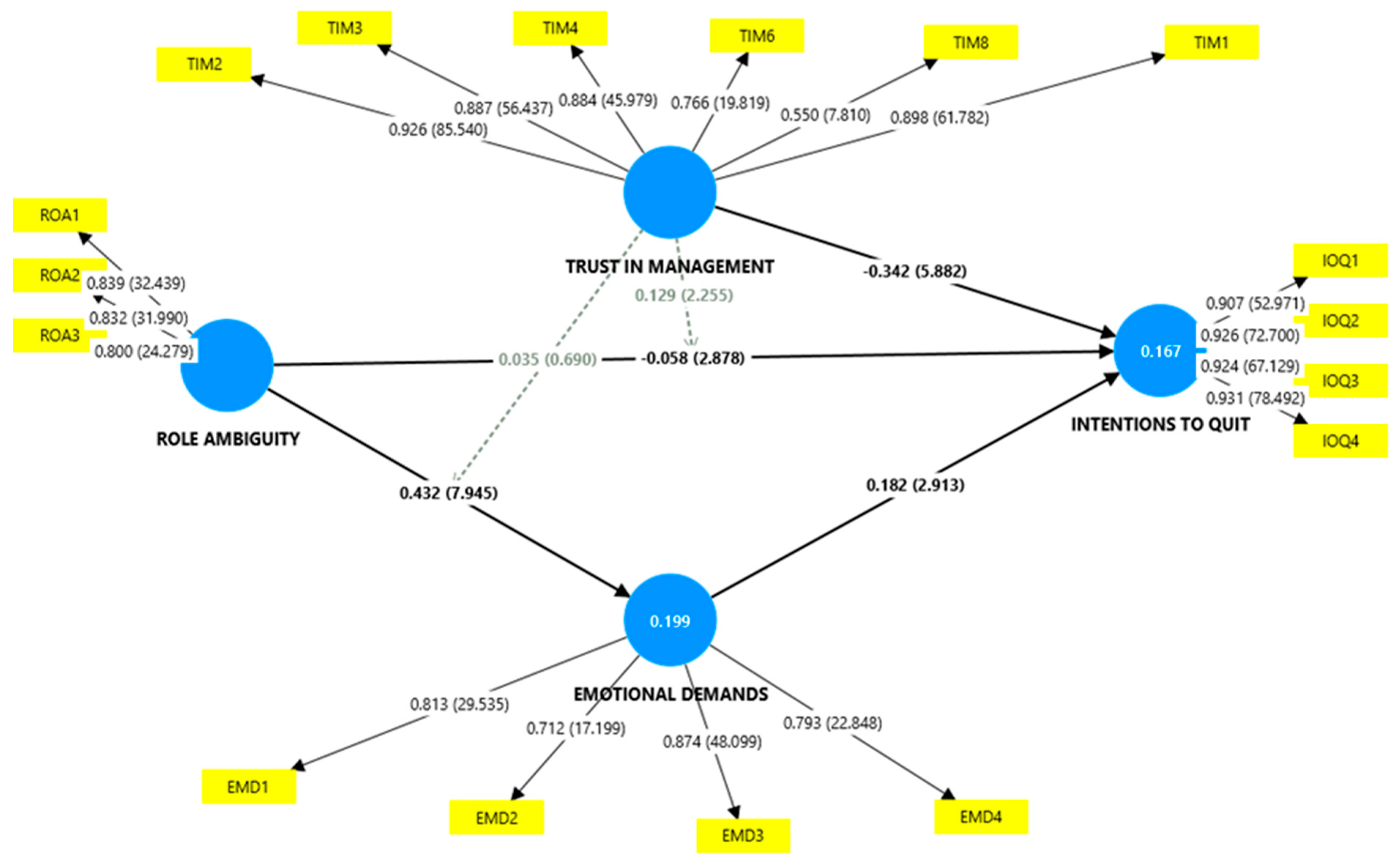

4.6. Assessing the Structural Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Discussion of Findings

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Managerial Implications

5.4. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Measurement Items

| Variables | Indicators |

| Emotional Demands (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004; Maxwell & Riley, 2017) | EMD |

| “Does your work put you in emotionally disturbing situations?” | EMD1 |

| “Do you have to relate to other people’s personal problems as part of your work?” | EMD2 |

| “Is your work emotionally demanding?” | EMD3 |

| “Do you get emotionally involved in your work?” | EMD4 |

| Intention to Quit (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004) | IOQ |

| “I sometimes think about changing jobs” | IOQ1 |

| “I sometimes think about looking for work outside this organization” | IOQ2 |

| “I intend to change jobs in the coming year” | IOQ3 |

| “I intend to look for work outside this organization in the coming year” | IOQ4 |

| Trust in Management (Mayer & Davis, 1999; Chao et al., 2004) | TIM |

| “I trust top managers at my organization” | TIM1 |

| “I have confidence in the integrity of my top managers” | TIM2 |

| “I am confident that top managers can make the right decisions” | TIM3 |

| “Top managers have a strong sense of integrity” | TIM4 |

| “Top managers’ actions are inconsistent with words” | TIM5 |

| “Top managers’ behaviors are guided by correct principles” | TIM6 |

| “If I had my way, I wouldn’t let top management have any influence over issues that are important to me” | TIM7 |

| “I would be willing to let top management have complete control over my future in this organization” | TIM8 |

| “I really wish I had a good way to keep an eye on top management” | TIM9 |

| “I would be comfortable giving top management a task or problem which was critical to me, even if I could not monitor their actions” | TIM10 |

| Role Ambiguity (Acker, 2004; Rizzo et al., 1970) | ROA |

| “In my job, I often feel like different people are “pulling me in different directions” | ROA1 |

| “I have to deal with competing demands at work” | ROA2 |

| “My superiors often tell me to do two different things that can’t both be done” | ROA3 |

| “The tasks I am assigned at work rarely come into conflict with each other” | ROA4 |

| “The things I am told to do at work do not conflict with each other” | ROA5 |

| “In my job, I’m seldom/rarely placed in a situation where one job duty conflicts with other job duties” | ROA6 |

References

- Acker, G. M. (2004). The effect of organizational conditions (role conflict, role ambiguity, opportunities for professional development, and social support) on job satisfaction and intention to leave among social workers in mental health care. Community Mental Health Journal, 40, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albalawi, A. S., Naugton, S., Elayan, M. B., & Sleimi, M. T. (2019). Perceived organizational support, alternative job opportunity, organizational commitment, job satisfaction and turnover intention: A moderated-mediated model. Organizacija, 52(4), 310–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, D. R., Andersen, L. P., Gadegaard, C. A., Høgh, A., Prieur, A., & Lund, T. (2017). Burnout among Danish prison personnel: A question of quantitative and emotional demands. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 45(8), 824–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S. U., Yoon, J. H., & Won, J. U. (2023). Association between high emotional demand at work, burnout symptoms, and sleep disturbance among Korean workers: A cross-sectional mediation analysis. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 16688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2018). Multiple levels in job demands-resources theory: Implications for employee well-being and performance. In E. Diener, S. Oishi, & L. Tay (Eds.), Handbook of well-being (pp. 1–13). Noba Scholar. [Google Scholar]

- Bowling, N. A., Khazon, S., Alarcon, G. M., Blackmore, C. E., Bragg, C. B., Hoepf, M. R., & Li, H. (2017). Building better measures of role ambiguity and role conflict: The validation of new role stressor scales. Work & Stress, 31(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenfetelli, R. T., & Bassellier, G. (2009). Interpretation of formative measurement in information systems research. MIS Quarterly, 33(4), 689–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cengiz, A., Yoder, L. H., & Danesh, V. (2021). A concept analysis of role ambiguity experienced by hospital nurses providing bedside nursing care. Nursing & Health Sciences, 23(4), 807–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, C. C., Ya-Ru, C., & Xin, K. (2004). Guanxi practices and trust in management: A procedural justice perspective. Organization Science, 15(2), 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-F., Lin, C. P., & Lien, G. Y. (2011). Modelling job stress as a mediating role in predicting turnover intention. Service Industries Journal, 31(8), 1327–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- De Beer, L. T., & Bianchi, R. (2017). Confirmatory factor analysis of the Maslach burnout Inventory. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 35(2), 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, D., & Belausteguigoitia, I. (2017). Reducing the harmful effect of role ambiguity on turnover intentions: The roles of innovation propensity, goodwill trust, and procedural justice. Personnel Review, 46(6), 1046–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T. K., & Henseler, J. (2015). Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Quarterly, 39(2), 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos Tome, J., & Van der Vaart, L. (2020). Work pressure, emotional demands and work performance among information technology professionals in South Africa: The role of exhaustion and depersonalisation. SA Journal of Human Resource Management/SA Tydskrif vir Menslikehulpbronbestuur, 18, a1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, J., Berthelsen, H., & Owen, M. (2020). Not all emotional demands are the same: Emotional demands from clients’ or co-workers’ relations have different associations with well-being in service workers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(21), 7738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfering, A., Grebner, S., Leitner, M., Hirschmüller, A., Kubosch, E. J., & Baur, H. (2017). Quantitative work demands, emotional demands, and cognitive stress symptoms in surgery nurses. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 22(5), 604–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statis-tics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisler, M., Berthelsen, H., & Hakanen, J. J. (2019). No job demand is an island—Interaction effects between emotional demands and other types of job demands. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, Y., Wen, Y., Chen, S. X., Liu, H., Si, W., Liu, Y., Wang, Y., Fu, R., Zhang, Y., & Dong, Z. (2014). When do salary and job level predict career satisfaction and turnover intention among Chinese managers? The role of perceived organizational career management and career anchor. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 23(4), 596–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Howard, M. C., & Nitzl, C. (2020). Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. Journal of Business Research, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., & Ray, S. (2021). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R: A workbook (p. 197). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hom, P. W., Lee, T. W., Shaw, J. D., & Hausknecht, J. P. (2017). One hundred years of employee turnover theory and research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(3), 530–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, R., & Olaleye, B. R. (2025). Relationship between workplace ostracism and job productivity: The mediating effect of emotional exhaustion and lack of motivation. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration, 17(1), 190–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ike, O. O., Ugwu, L. E., Ibeawuchi, K., Enwereuzor, I. K., Eze, I. C., Omeje, O., & Okonkwo, E. (2023). Expanded-multidimensional turnover intentions: Scale development and validation. BMC Psychology, 11(1), 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, A., Sengupta, S., Panda, M., Hati, L., Prikshat, V., Patel, P., & Mohyuddin, S. (2022). Teleworking: Role of psychological well-being and technostress in the relationship between trust in management and employee performance. International Journal of Manpower, 45(1), 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L., & Probst, T. M. (2019). The moderating effect of trust in management on consequences of job insecurity. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 40(2), 409–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkman, B. (2018). Concept analysis: Role ambiguity in senior nursing students. Nursing Forum, 53(2), 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karahan Kaplan, M., Bozkurt, G., Aksu, B. Ç., Bozkurt, S., Günsel, A., & Gencer Çelik, G. (2024). Do emotional demands and exhaustion affect work engagement? The mediating role of mindfulness. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1432328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khumalo, N., & Jackson, L. (2022, September 25–28). The link between perceived role conflict and employee attitudes in a public sector context: A moderated mediation model of trust in management and core self-evaluation. 2022 International Business Conference (p. 1336), Western Cape, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. (2005). Principles and practices of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Komodromos, M., Halkias, D., & Harkiolakis, N. (2019). Managers’ perceptions of trust in the workplace in times of strategic change: The cases of Cyprus, Greece and Romania. EuroMed Journal of Business, 14(1), 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y., & Eissenstat, S. J. (2018). A longitudinal examination of the causes and effects of burnout based on the job demands-resources model. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 18, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legood, A., van der Werff, L., Lee, A., & Den Hartog, D. (2020). A meta-analysis of the role of trust in the leadership-performance relationship. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 30(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Roux, R., & Cohen, T. (2016). Understanding the limitations to the right to strike in essential and public services in the SADC region. Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal/Potchefstroomse Elektroniese Regsblad, 19(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapetla, M., & Letete, E. (2020). Bureaucratic inefficiencies in the public sector of Lesotho: Implications for service delivery. African Journal of Public Administration, 12(3), 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Martini, M. (2024). The impact of job ambiguity and work stress as intervening variable on turnover intention among employees. Value Added: Majalah Ekonomi dan Bisnis, 20(2), 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, A., & Riley, P. (2017). Emotional demands, emotional labour and occupational outcomes in school principals: Modelling the relationships. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 45(3), 484–502. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, R. C., & Davis, J. H. (1999). The effect of the performance appraisal system on trust for management: A field quasi-experiment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(1), 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwakyusa, J. R., & Mcharo, E. W. (2024). Role ambiguity and role conflict effects on employees’ emotional exhaustion in healthcare services in Tanzania. Cogent Business & Management, 11(1), 2326237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naim, M. F., & Ozyilmaz, A. (2023). Flourishing-at-work and turnover intentions: Does trust in management moderate the relationship? Personnel Review, 52(7), 1878–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntoi, K., & Makoa, F. (2022). Public service delivery challenges in Lesotho: A governance perspective. African Journal of Governance and Development, 11(2), 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Olaleye, B. R., Babatunde, B. O., Lekunze, J. N., & Tella, A. R. (2023). Attaining organizational sustainability through competitive intelligence: The roles of organizational learning and resilience. Journal of Intelligence Studies in Business, 13(3), 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaleye, B. R., & Lekunze, J. N. (2023). Emotional intelligence and psychological resilience on workplace bullying and employee performance: A moderated-mediation perspective. Journal of Law and Sustainable Development, 12(1), e2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaleye, B. R., Lekunze, J. N., Sekhampu, T. J., Khumalo, N., & Ayeni, A. A. W. (2024). Leveraging innovation capability and organizational resilience for business sustainability among small and medium enterprises: A PLS-SEM approach. Sustainability, 16, 9201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridjal, S., & Muhammadin, A. (2023). Role ambiguity and work environment on turnover intention with work stress as moderation: Case study at bank Rakyat Indonesia. International Journal of Scientific Research and Management (IJSRM), 11(06), 4967–4976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, J. R., House, R. J., & Lirtzman, S. I. (1970). Role conflict and ambiguity in complex organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 15, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(3), 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Taris, T. W. (2014). A critical review of the job demands-resources model: Implications for improving work and health. In G. F. Bauer, & O. Hämmig (Eds.), Bridging occupational, organizational and public health: A transdisciplinary approach (pp. 43–68). Springer Science and Business Media. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S., Roesler, U., Kusserow, T., & Rau, R. (2014). Uncertainty in the workplace: Examining role ambiguity and role conflict, and their link to depression—A meta-analysis. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 23(1), 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Showail, S. J., McClean Parks, J., & Smith, F. L. (2013). Foreign workers in Saudi Arabia: A field study of role ambiguity, identification, information-seeking, organizational support and performance. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(21), 3957–3979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. C. (2011). Role ambiguity and role conflict in nurse case managers: An integrative review. Professional Case Management, 16(4), 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teh, P. L., Yong, C. C., & Lin, B. (2014). Multidimensional and mediating relationships between TQM, role conflict and role ambiguity: A role theory perspective. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 25(11–12), 1365–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, M. K., Jimmieson, N. L., & Bordia, P. (2020). Employees’ perceptions of their own and their supervisor’s emotion recognition skills moderate emotional demands on psychological strain. Stress and Health, 36(2), 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W., Mather, K., & Seifert, R. (2018). Job insecurity, employee anxiety, and commitment: The moderating role of collective trust in management. Journal of Trust Research, 8(2), 220–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winarno, A., Prasetio, A. P., Luturlean, B. S., & Wardhani, S. K. (2022). The link between perceived human resource practices, perceived organisational support and employee engagement: A mediation model for turnover intention. SA Journal of Human Resource Management/SA Tydskrif vir Menslikehulpbronbestuur, 20, a1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y. W., & Wong, Y. T. (2017). The effects of perceived organisational support and affective commitment on turnover intention: A test of two competing models. Journal of Chinese Human Resource Management, 8(1), 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2021). Public sector governance in Lesotho: Challenges and reform pathways. World Bank Group. [Google Scholar]

- Yousaf, A., Sanders, K., & Abbas, Q. (2015). Organizational/occupational commitment and organizational/occupational turnover intentions: A happy marriage? Personnel Review, 44(4), 470–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapf, D., Kern, M., Tschan, F., Holman, D., & Semmer, N. K. (2021). Emotion work: A work psychology perspective. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 8(1), 139–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Wu, C., Yan, J., Liu, J., Wang, P., Hu, M., Liu, F., Qu, H., & Lang, H. (2023). The relationship between role ambiguity, emotional exhaustion and work alienation among Chinese nurses two years after COVID-19 pandemic: Across-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry, 23(1), 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q., Martinez, L. F., Ferreira, A. I., & Rodrigues, P. (2016). Supervisor support, role ambiguity and productivity associated with presenteeism: A longitudinal study. Journal of Business Research, 69(9), 3380–3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Categories | Freq (n = 290) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 130 | 44.8 |

| Female | 160 | 55.2 | |

| Age | Below 20 years | 13 | 4.5 |

| 20–29 years | 79 | 27.2 | |

| 30–39 years | 140 | 48.3 | |

| 40–49 years | 44 | 15.2 | |

| Above 50 years | 14 | 4.8 | |

| Highest Educational Level | College certificate | 24 | 8.3 |

| Diploma | 34 | 11.7 | |

| Degree | 176 | 60.7 | |

| Masters | 37 | 12.8 | |

| Others | 19 | 6.6 | |

| Ministry | Agriculture & Food Security | 69 | 23.8 |

| Communication, Science & Technology | 45 | 15.5 | |

| Development Planning | 27 | 9.3 | |

| Finance | 57 | 19.7 | |

| Small Business Development | 36 | 12.4 | |

| Tourism, Environment & Culture | 25 | 8.6 | |

| Trade & Industry | 31 | 10.7 | |

| Years of Operation | Below 5 years | 97 | 33.4 |

| 5–10 years | 80 | 27.6 | |

| 11–15 years | 67 | 23.1 | |

| 16–25 years | 32 | 11.0 | |

| Above 25 years | 14 | 4.8 | |

| Position | Non-Managerial | 115 | 39.7 |

| Supervisory/Front-Line Manager | 62 | 21.4 | |

| Middle Management Level | 64 | 22.1 | |

| Senior Management Level | 28 | 9.7 | |

| Others | 21 | 7.2 |

| Variables | EMD | IOQ | ROA | TIM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Demand (EMD) | - | 1.249 | - | - |

| Intentions to Quit (IOQ) | - | - | - | - |

| Role Ambiguity (ROA) | 1.047 | 1.281 | - | - |

| Trust in Management (TIM) | 1.055 | 1.058 | - | - |

| Indicators | Values | Threshold Criteria | Rating |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) | 0.062 | Below 0.08 | Good fit |

| Normed Fit Index (NFI) | 0.901 | Value close to 1 | Good fit |

| Chi-Square (χ2) | 11,072.795 | Good fit |

| Variables | Loadings (λ) | CA | Rho_A | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Demands | 0.813 | 0.832 | 0.876 | 0.640 | |

| EMD1 | 0.813 *** | ||||

| EMD2 | 0.712 *** | ||||

| EMD3 | 0.874 *** | ||||

| EMD4 | 0.793 *** | ||||

| Intention to Quit | 0.941 | 0.942 | 0.958 | 0.850 | |

| IOQ1 | 0.907 *** | ||||

| IOQ2 | 0.926 *** | ||||

| IOQ3 | 0.924 *** | ||||

| IOQ4 | 0.931 *** | ||||

| Trust in Management | 0.905 | 0.944 | 0.928 | 0.687 | |

| TIM1 | 0.898 *** | ||||

| TIM2 | 0.926 *** | ||||

| TIM3 | 0.887 *** | ||||

| TIM4 | 0.884 *** | ||||

| TIM5 | - | ||||

| TIM6 | 0.766 *** | ||||

| TIM7 | - | ||||

| TIM8 | 0.550 *** | ||||

| TIM9 | - | ||||

| TIM10 | - | ||||

| Role Ambiguity | 0.763 | 0.767 | 0.864 | 0.678 | |

| ROA1 | 0.839 *** | ||||

| ROA2 | 0.832 *** | ||||

| ROA3 | 0.800 *** | ||||

| ROA4 | - | ||||

| ROA5 | - | ||||

| ROA6 | - |

| Variables | EMD | IOQ | ROA | TIM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Demand (EMD) | a 0.800 | b 0.228 | 0.554 | 0.155 |

| Intentions to Quit (IOQ) | 0.208 | 0.922 | 0.117 | 0.357 |

| Role Ambiguity (ROA) | 0.443 | 0.095 | 0.824 | 0.249 |

| Trust in Management (TIM) | −0.137 | −0.342 | −0.212 | 0.829 |

| Hypotheses | Std. Beta | Std. Error | t-Value | p-Value | F2 | R2 | Decision | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | 0.103 | 0.036 | 2.034 | 0.003 | 0.163 | 0.143 | S | |

| H2 | 0.442 | 0.054 | 8.525 | 0.000 | 0.223 | 0.196 | S | |

| Indirect Effects (mediation and moderation) | ||||||||

| H3 | 0.079 | 0.030 | 2.659 | 0.008 | Full Mediation | S | ||

| H4 | 0.129 | 0.057 | 2.255 | 0.024 | 0.025 | S | ||

| H5 | 0.035 | 0.051 | 0.690 | 0.490 | 0.002 | NS | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khumalo, N.; Olaleye, B.R. Emotional Demands and Role Ambiguity Influence on Intentions to Quit: Does Trust in Management Matter? Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 424. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110424

Khumalo N, Olaleye BR. Emotional Demands and Role Ambiguity Influence on Intentions to Quit: Does Trust in Management Matter? Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(11):424. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110424

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhumalo, Ntseliseng, and Banji Rildwan Olaleye. 2025. "Emotional Demands and Role Ambiguity Influence on Intentions to Quit: Does Trust in Management Matter?" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 11: 424. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110424

APA StyleKhumalo, N., & Olaleye, B. R. (2025). Emotional Demands and Role Ambiguity Influence on Intentions to Quit: Does Trust in Management Matter? Administrative Sciences, 15(11), 424. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110424