1. Introduction

A micro-entrepreneur is an individual who starts and operates a very small business venture, typically with limited resources, capital, and staffing (e.g.,

Alshebami, 2025b). These businesses, known as micro-enterprises or micro-businesses, are generally characterized by having fewer than ten employees, often just one, and requiring minimal initial investment. Examples of micro-entrepreneurs include freelancers, home-based businesses, small-scale retailers, and rideshare drivers, among others (e.g.,

Tamvada, 2021, Chapter 1).

Micro-entrepreneurs play a vital role in economic development, especially in developing countries, by generating income, creating jobs, and fostering innovation at the grassroots level (e.g.,

Ruiz-Martínez & Quiroz-Rojas, 2022;

Jayachandran, 2021;

Ruiz-Martínez et al., 2021;

Meressa, 2020). In that sense, micro-entrepreneurship is considered a vehicle for empowering individuals and communities, which involves the intersection of gender, social capital, and entrepreneurship (

Crittenden & Crittenden, 2021;

Tamvada, 2021, Chapter 2). In recent years, digital platforms and mobile technologies have reshaped how micro-entrepreneurs operate, enabling broader market access and lowering barriers to entry (e.g.,

Pawełoszeka et al., 2023).

The challenges small businesses face during difficult times, such as economic downturns or crises, have often been overlooked in academic research, with most studies focusing on how large corporations respond to critical situations (e.g.,

Fairlie, 2020;

Childs et al., 2022;

Fuming et al., 2022;

Chapman Cook & Karau, 2023;

Fairlie et al., 2023;

Matikonis & Graham, 2024;

Scapini & Vergara, 2024;

Alshebami, 2025a,

2025b). In this sense, small businesses frequently encounter different forms of market uncertainty, and studies show that a proactive approach is key to adapting. By developing resilience, embracing innovation and agility, and building strong connections with customers and partners, small businesses can do more than just endure; they can convert adversity into advantage (e.g.,

Chapman Cook & Karau, 2023;

Alshebami, 2025a,

2025b).

Filling this significant gap in the literature, this study offers new evidence on how small businesses adapted to the COVID-19 pandemic by analyzing its impact on micro-entrepreneurial activities in Chile. In doing so, this study makes several key contributions. First, this research provides valuable insights into the Chilean context, where micro-enterprises play a significant role in the country’s economy, contributing to job creation and economic growth. Indeed, according to the Chile Internal Revenue Service, micro-firms accounted for 72% of all registered companies and 8% of permanent jobs in 2023. By focusing on Chilean micro-entrepreneurs, the study offers a geographically specific understanding of crisis adaptation.

Second, the novelty of this analysis lies in its comprehensive approach, considering a range of economic and social factors impacting micro-entrepreneurial activities. This includes crucial elements such as capital endowment, time allocated to domestic and caregiving duties, business location, and business formalization—factors often overlooked in broader studies.

Furthermore, by utilizing data from the 6th and 7th Micro-entrepreneurship Surveys (EME) conducted before and after the pandemic, this research offers a unique longitudinal perspective. This allows for an examination of trends before, during, and after the crisis, contributing to a deeper understanding of the long-term implications of global crises on micro-entrepreneurship.

Finally, the study’s findings offer practical implications by underscoring the importance of specific policy interventions. The research highlights the need for policies that address barriers to business formalization, gendered constraints, and support opportunity-driven entrepreneurship in the post-crisis economic recovery phase, among others.

Findings can be classified into three aspects. (i) Pandemic effects and digital substitution: During the pandemic, the study found a digitalization-formality trade-off in achieving sales growth. Specifically, sales were positively associated with intensive Internet usage, indicating that digital channels served as a low-cost substitute for formal compliance when administrative capacity was strained. Conversely, business registration and municipal permits did not necessarily contribute to more sales, suggesting that the benefits of formality were outweighed by its costs during the acute phase of the crisis. (ii) Formality’s enduring drivers and post-shock decline: The research isolates the factors that typically drive formality in this post-shock environment. Business formality was positively influenced by capital endowment and opportunity-driven entrepreneurship, confirming that formality remained complementary to growth strategies requiring investment. However, formality was negatively associated with time spent on unpaid work, highlighting a gendered constraint mechanism. Critically, formality levels decreased for both men and women post-pandemic, underscoring a lasting reluctance or inability to reintegrate into the formal system after the shock. (iii) Entrepreneurial motivation and trajectory: The analysis maps the trajectory of entrepreneurial motivation, noting that the crisis fueled a wave of necessity-driven businesses. As the economy recovered, the post-pandemic period saw renewed incentives for opportunity-driven entrepreneurs, whose growth orientation and higher capital drove the demand for the re-emerging complementarity of formal institutions.

This article is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents a conceptual framework for research hypothesis development.

Section 3 presents the data and refers to methodological aspects.

Section 4 and

Section 5 present and discuss the empirical findings, respectively.

Section 6 closes by summarizing the main conclusions, presenting policy implications, and suggesting future research topics.

3. Data and Methodological Aspects

3.1. Data

This study is based on the 6th and 7th waves of the Micro-entrepreneurship Survey (EME), which are freely available at

http://www.economia.gob.cl/category/estudios-encuestas/encuestas-y-bases-de-datos (accessed on 10 November 2024). The EME has been jointly prepared by the Chilean Ministry of Economy, Development and Tourism and the National Institute of Statistics (INE) since 2013. To date, it is the main instrument for characterizing formal and informal micro-enterprises in the country, providing relevant data for the development and monitoring of public policies in this area. The EME is based on the National Employment Survey (ENE), is nationally and regionally representative, and analyses individuals who are self-employed or own a micro-enterprise with up to 10 employees. It is important to note that the EME does not follow the same group of individuals over time as a panel survey would.

Fieldwork for the sixth and seventh editions of the EME was conducted in May–August 2019 and May–August 2022, respectively. According to the 6th EME, in 2019 there were 2,057,903 micro-entrepreneurs, of which 53.1% were informal and 46.9% formal. Reasons frequently given for not carrying out the formalization procedures with Chile’s Internal Revenue Service (SII) were that the business was too small, or the activity was infrequent, and registration was not essential for the operation of the business. In 2019, 61.4% of respondents were men and 38.6% were women. Women had a higher prevalence of self-employment (89.9%) than men (81.3%).

In turn, in 2022 there were 1,977,426 micro-entrepreneurs, of which 41.7% were women and 59.3% men. About 41.7% of micro-entrepreneurs were formal, a figure slightly lower than that of 2019. Similarly to 2019, the prevalence of self-employment among women was higher, reaching 92.6% compared with 86.3% of men. As a result of COVID-19, there were 410,955 (20.8%) micro-entrepreneurs who started their activity. Of these, 207,586 were women and 203,369 were men, representing 25.8% and 17.3% of micro-enterprises owned by women and men, respectively.

3.2. Descriptive Statistics

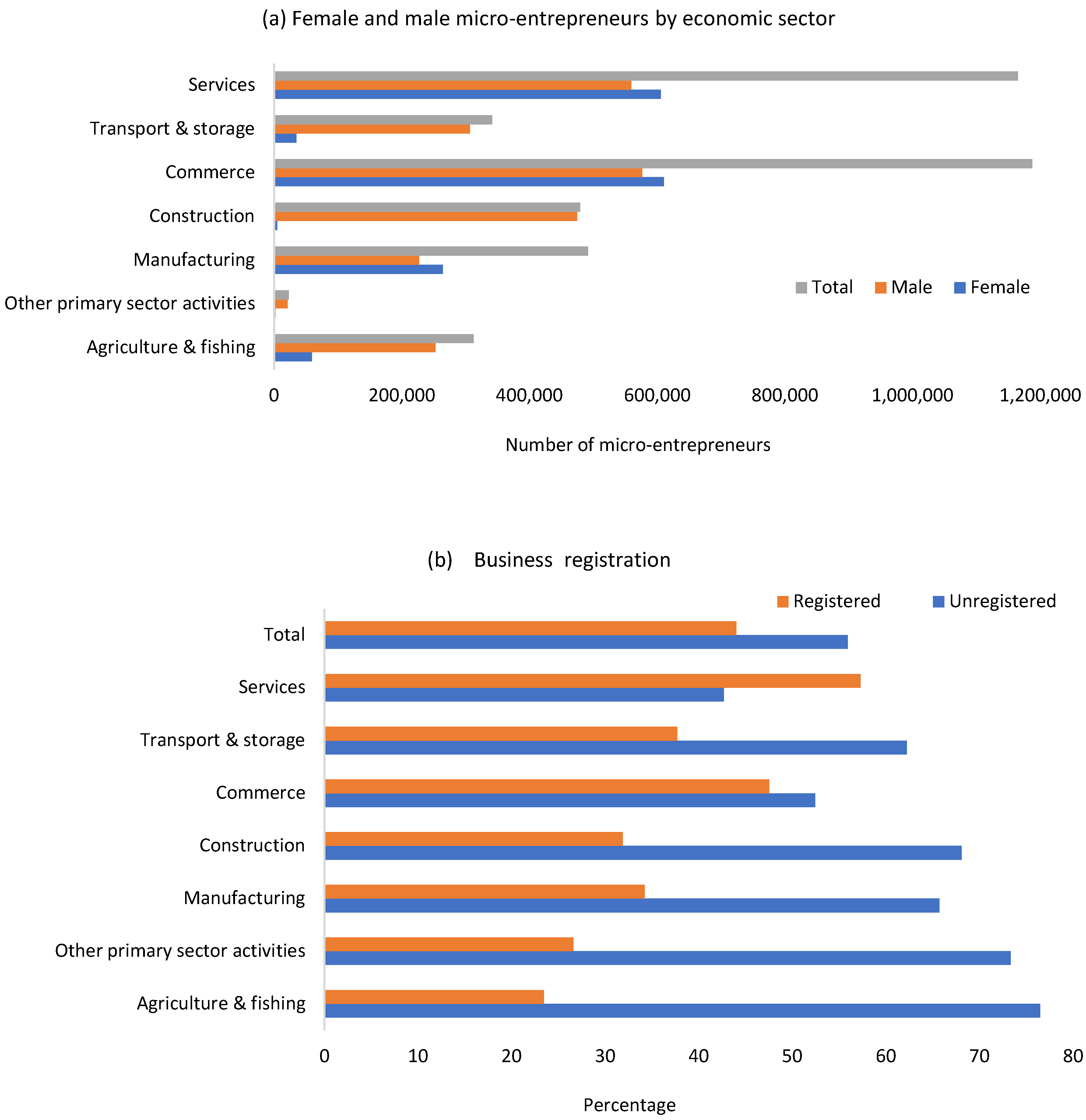

Figure 2a,b depict figures from the merged EMEs 6 and 7, while

Figure 3a–c depicts those from COVID-19-related questions contained in EME 7. As shown in

Figure 2a, men and women were concentrated in Commerce (1,187,689 micro-entrepreneurs in total) and Services (1,165,535 micro-entrepreneurs in total). As for business registration by sector,

Figure 2b shows that the highest rate of registration was in Services (57.3%) while the lowest rate was in Agriculture & Fishing (23.5%).

Figure 3a in turn shows that around 21% of businesses were started due to COVID-19. Among entrepreneurs who started for this reason,

Figure 3b shows that the most frequent motivation was necessity (70.8%) followed by opportunity (23.7%).

Figure 3c shows the main sources of financing for business expenses (i.e., raw materials, salaries, bills, among others) recorded by EME 7. As can be seen, personal savings and business income were the most important sources for men (16% and 79%, respectively) and women (19% and 76%, respectively). Other sources of financing available during the pandemic, such as emergency family income (IFE), government programs, and pension fund withdrawals, represented individually a negligible share (0.41%, 0.45%, and 0.58%, respectively, for the group of men and women).

3.3. Methodological Aspects

This study uses binary/multinomial logistic and quantile regression models and treatment-effects estimation for observational data—regression adjustment (RA) and nearest-neighbor matching (NNM). Treatment-effects estimation refers to the process of quantifying the causal impact of a treatment, intervention, or exposure on an outcome of interest in observational (non-randomized) data. Unlike randomized controlled trials, where treatment assignments are random, observational data often suffers from confounding and selection bias, making causal inference challenging (e.g.,

Stuart, 2010).

RA controls covariates’ influence by fitting separate outcome regressions for each treatment level. The average treatment effect (ATE) is then estimated as the difference between the averages of the predicted outcomes across all data points (e.g.,

Perraillon et al., 2020). NNM in turn estimates the missing potential outcome for each subject by averaging the outcomes of similar individuals who received the opposite treatment. Similarity is determined by a weighted function of the covariates. The treatment effect is the average difference between the observed and imputed potential outcomes for all individuals (

Stuart, 2010).

In essence, both RA and matching are powerful, indispensable tools for controlling observed confounding. They enhance the validity of causal inferences in observational studies by making treatment groups as comparable as possible on measurable factors, such as education and prior experience in the entrepreneurial context (EME), though they cannot address unobserved heterogeneity directly.

4. Empirical Findings

This section is organized into three distinct subsections.

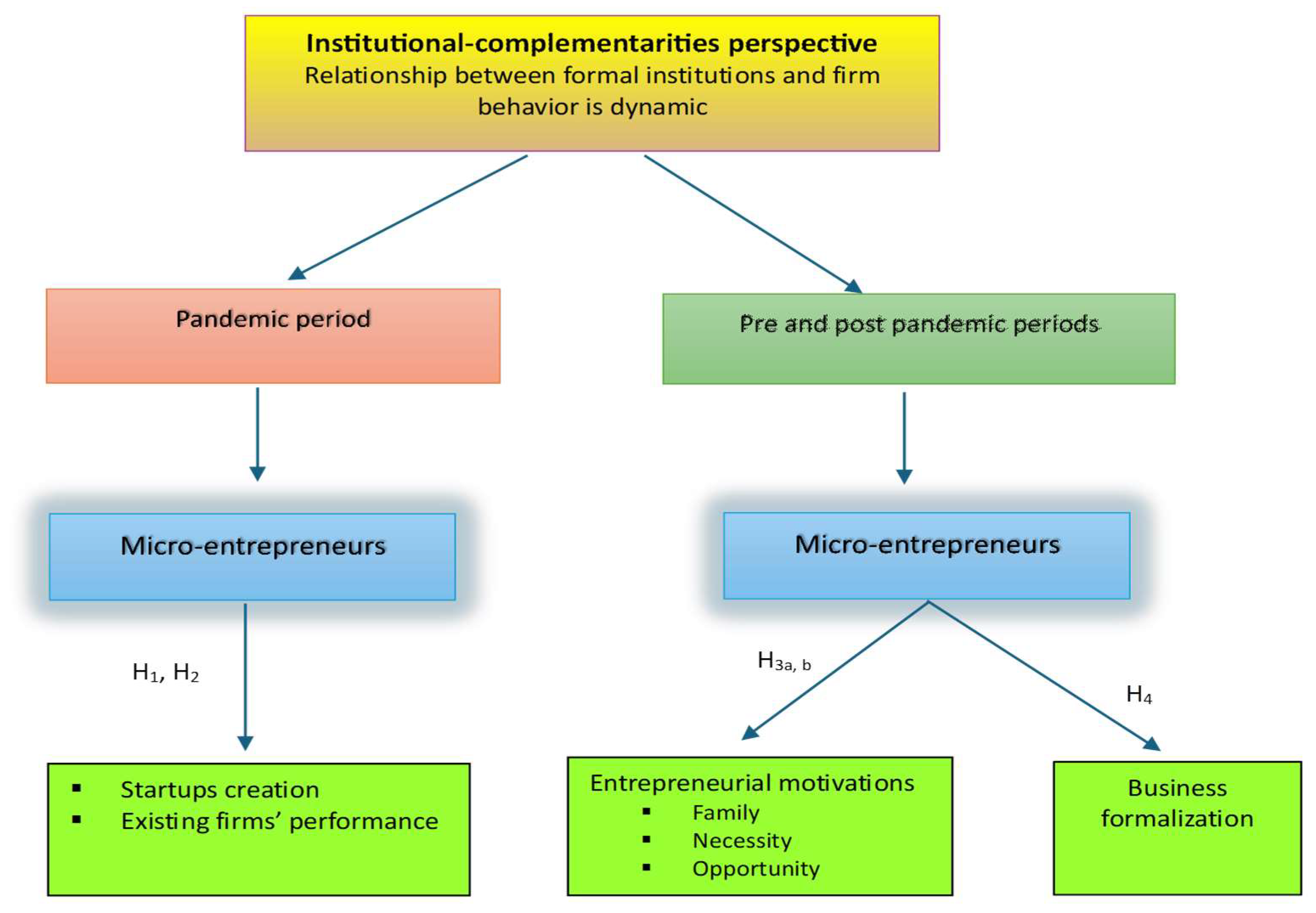

Section 4.1 is dedicated to testing hypotheses H

1 and H

2, utilizing binary logistic and quantile regression analyses on the COVID-19-related questions in EME7. Subsequently,

Section 4.2 and

Section 4.3 address the testing of H

3a, H

3b, and H

4, employing binary and multinomial logistic regression models, as well as RA and NNM methodologies, based on data from EMEs 6 and 7. All statistical models, which are fitted with Stata 19, consider EME expansion factors.

4.1. Business Entry and Increased Sales Due to COVID-19: Evidence from EME 7

4.1.1. Entry

Table 1 shows binary logistic regression models for the decision to start a business due to the pandemic for men, women, and both groups. The independent variables of interest are entrepreneurial motivation and gender. Control variables include demographics—age, education, breadwinner status, marital status, foreign citizenship, and capital wealth percentile; entrepreneurial experience, training for current economic activity, the ratio of unpaid to paid working hours, health and pension plans, and geographic region (e.g.,

Ruiz-Martínez & Quiroz-Rojas, 2022). Parameter estimates are expressed as odds ratios so that a given predictor variable is positively (negatively) associated with the dependent variable if its odds ratio is greater (less) than 1.

Regression results for men and women—columns (1) and (2)—show that new entrepreneurs were most likely young, single, educated, untrained, foreign-born, necessity driven, endowed with low levels of capital wealth, and non-breadwinners. Results for the full sample reported in column (3) also indicate that new entrepreneurs were less likely to be men. Indeed, the likelihood of starting a new business for a man was about 3 percentage points lower. This lends support to H1. From columns (1) through (3), it is apparent that individuals with a relatively higher share of unpaid working hours were pushed into entrepreneurship.

4.1.2. Sales

Table 2 reports logistic regression models for the likelihood that a business increased its sales due to the pandemic. The independent variables of interest are increased Internet usage, formal (registered) business, and age of the business. In addition to the control variables of

Table 1, business-related variables are considered: accounting usage, municipal permit, location (home-based), existence of personnel, and economic sector—services, where the baseline is selling goods/products. In this regard, EME treats goods and products interchangeably as one single category.

It is worth noting that the regression models of

Table 2 incorporate controls for education, training, and prior entrepreneurial experience, which measure entrepreneurial abilities. These abilities are in turn associated with capital accumulation and proficiency in Internet use. Taking these variables into consideration aims to mitigate potential omitted variable bias stemming from observable abilities. However, the influence of unobservable abilities remains a potential source of bias that is difficult to quantify.

As shown, more intensive Internet usage contributed to more sales. In the full sample, the likelihood of more sales for those businesses using the Internet more intensively increased by 5.5 percentage points.

1 Sales also increased with higher levels of capital wealth, help of staff members, accounting usage (men and full sample regressions), and working from home. In contrast, registering one’s business or running an established business reduced the odds of increasing sales (with marginal impacts of −1.7 and −5.5 percentage points, respectively, in the full sample); similarly, for obtaining a municipal permit (a marginal impact of −3.7 percentage points in the full sample). This evidence lends support to H

2. Furthermore, businesses offering services were less likely to increase their sales than those offering goods or products.

In terms of entrepreneurial characteristics, individuals with education and training, not necessarily with entrepreneurial experience, foreign-born and young were more likely to see their sales increase during the pandemic. In contrast, those entrepreneurs who spent relatively more hours on housework and caregiving saw their chances of increased sales decrease. The regression model for the full sample suggests that men were more likely to increase their sales. In the case of marital and breadwinner status, their impact depended on the gender of the entrepreneur. For example, married women were more likely to increase their sales during the pandemic.

Table 3 complements the above evidence by reporting quantile regressions for logarithmic sales of men, women, and both groups. The advantage of quantile regressions is that they allow quantifying how the impact of covariates changes when moving from low to high sales levels (e.g.,

Hao & Naiman, 2007, Chapter 3). The quantiles considered are the 25th, 50th, and 75th. As reported in columns (1) through (3), business registration had a positive and increasing impact on men’s sales. This evidence goes in line with what was discussed in

Section 2.2.4, as to the potential benefits of business registration. However, this was not the case for women. For example, for the 50th and 75th quantiles, registration had no discernible impact on women’s log(sales).

In turn, the impact of personnel on log(sales) was consistently positive and increasing for men, women, and both groups. Interestingly, unpaid work hours negatively affected only the 25th quantile of log(sales) for men and women. Meanwhile, being a breadwinner encouraged sales, but only in the 25th quantile when men and women are analyzed separately, and in the 25th and 75th quantiles for the entire sample. Other covariates, such as municipal permit and Internet usage, were positively associated with log(sales), but their numerical magnitudes were not necessarily increasing with the log(sales) quantile.

4.2. Family-, Necessity- and Opportunity-Driven Micro-Entrepreneurs: Evidence from EME 6 & 7

Table 4 presents a multinomial logistic regression for entrepreneurial motivations—family tradition, necessity (baseline), and opportunity—for the combined surveys of 2019 and 2022. The sample of interest is relatively new entrepreneurs, who have been in business for 12 years or less. It is important to note that by combining both surveys, it is not possible to isolate a group of new micro-entrepreneurs only. Indeed, EME 6 allows the identification of micro-entrepreneurs who had been in business for nine years or less at the time of the survey, while EME 7 allows the identification of those who had been in business for two years or less, or 12 years or less at the time of the survey. These three groups are therefore considered to be relatively new micro-entrepreneurs.

The independent variables of interest are formal business, capital wealth, and a time fixed effect for the post-pandemic year of 2022 (where the baseline is 2019). Control variables include entrepreneur characteristics (gender, age, foreign citizenship, education), personnel, health and pension plans, time dedicated to domestic work and caregiving, regional and sector fixed effects. Parameter estimates are expressed as relative risk ratios, which can be interpreted as the change in the odds or relative risk of being in a particular category (e.g., motivation), relative to the baseline, for a one-unit change in a predictor variable when holding other predictor variables constant. As in a binary logistic model, a positive (negative) regression coefficient in a multinomial logistic model corresponds to a relative-risk (odds) ratio greater (less) than 1.

As shown in columns (1) and (2), family and opportunity-driven entrepreneurs were more likely to run formal (and staffed) businesses, relative to the baseline of necessity-driven entrepreneurs. (For example, the marginal impact of a formal business in the likelihood of observing a family- or opportunity-driven entrepreneur was 2.6 or 12.9 percentage points, respectively). Opportunity-driven entrepreneurs were likely to belong to the upper 33-percentile of capital wealth, and to be male, single, foreign-born, educated, with health and pension plans. Family-driven entrepreneurs shared most of these characteristics, except that they were more likely to be domestic citizens, less educated, and without access to a health plan. This evidence lends support to H3a.

The estimation results also suggest that the odds of opportunity-driven entrepreneurship increased in 2022, relative to necessity-driven entrepreneurship (with corresponding marginal impacts of 3.0 and −2.3 percentage points). This result is somehow expected because quarantine periods ended in 2021, so Chile’s economy fully opened the following year. This brought new business opportunities, as economic sectors took their path to recovery. Nevertheless, H3b receives partial support, as family entrepreneurship did not gain more share than necessity entrepreneurship after the pandemic. It is possible that, while family entrepreneurship is typically associated with long-term goals and, potentially greater resources, continued economic instability may have increased risk aversion among individuals and families. Furthermore, the pandemic could have depleted family savings or limited their resources, making it difficult to launch ventures that often require greater initial investment and planning.

4.3. Evolution of Formalization

Table 5, columns (1)–(3), presents logistic regression models for the likelihood of business registration for men, women, and both groups for the combined surveys of 2019 and 2022. As shown at the top of the table, formalization became less likely for men, women, and both groups in the post-pandemic period (with corresponding marginal impacts of −3.2, −2.4, and −2.9 percentage points). For example, the odds for women of registering their businesses fell by 21.3% in 2022 relative to 2019. These odds fell even more for men (28.6%). This evidence lends support to H

4.

From the three columns, it is consistently the case that business registration was positively associated with high levels of capital wealth, marriage, senior age, education, training, opportunity, Internet usage, pension/health plan access, and having staff, while it was inversely associated with business age and time devoted by their owners/managers to unpaid work. This evidence agrees with the findings of

Ruiz-Martínez and Quiroz-Rojas (

2022).

Table 6 presents further evidence in this regard. Specifically, panel (a), (i) through (iii), reports RA-based estimates of business registration rates for 2019 and 2022. In this case, the treatment corresponds to the post-pandemic period. Regression models for the control and treatment groups are based on the specification of

Table 5. From (i) through (iii), one sees that business registration fell by 1.7 percentage points in the full sample, and by 1.5 and 2.2 percentage points in the subgroups of men and women, respectively. For example, the estimated registration rate in the full sample for 2019 was 44.6%, with a 95% confidence interval of (43.4%, 45.8%), while that for 2022 was 42.9%, with a 95% confidence interval of (41.5%, 44.82%).

Panel (b) complements this evidence by presenting average treatment effects (ATEs) based on NNM. The covariates used to match individuals in the treatment and control groups are the same as those of the regression adjustment. As shown, the ATEs suggest that registration rates fell in the post-pandemic period by a greater extent than what regression adjustment predicted: 4.2, 4.6, and 5.0 percentage points in the full sample, men subgroup, and women subgroup, respectively. These estimates are closer to the figures observed in EME 6 & 7. For example, among women, business registration rate fell by 4.6 percentage points, from 41.32% to 36.75%, while that of men fell by 4.4 percentage points, from 45.39% to 40.96%, when comparing the samples of 2022 and 2019.

It should be noted that the estimates from both the RA and NNM approaches rely on the strong assumption of selection on observables. This means they only adjust for differences between the pre- and post-pandemic periods (treatment and control groups) that are captured by the covariates included in the models (i.e., the observable characteristics). Consequently, these methods do not account for potential differences due to unobservable factors (such as inherent risk tolerance, psychological impacts of the pandemic, or pre-existing unmeasured skills) that might simultaneously influence both the likelihood of being in the treatment period and the business registration rate. Therefore, the reported estimates should be interpreted as measures of association or conditional average effects, not necessarily as the true causal effect of the post-pandemic period if unobservable confounders are present.

In summary, H1 (economic necessity spurs female entrepreneurship), H2 (Internet use boosts sales for new micro-businesses), H3a (capital-endowed and registered businesses driven by family and opportunity), and H4 (post-pandemic decrease in new business registration) were empirically supported while H3b (post-pandemic rise in family- and opportunity-driven entrepreneurship) was only partially supported (because of no evidence of post-pandemic rise in family-driven entrepreneurship).

5. Discussion

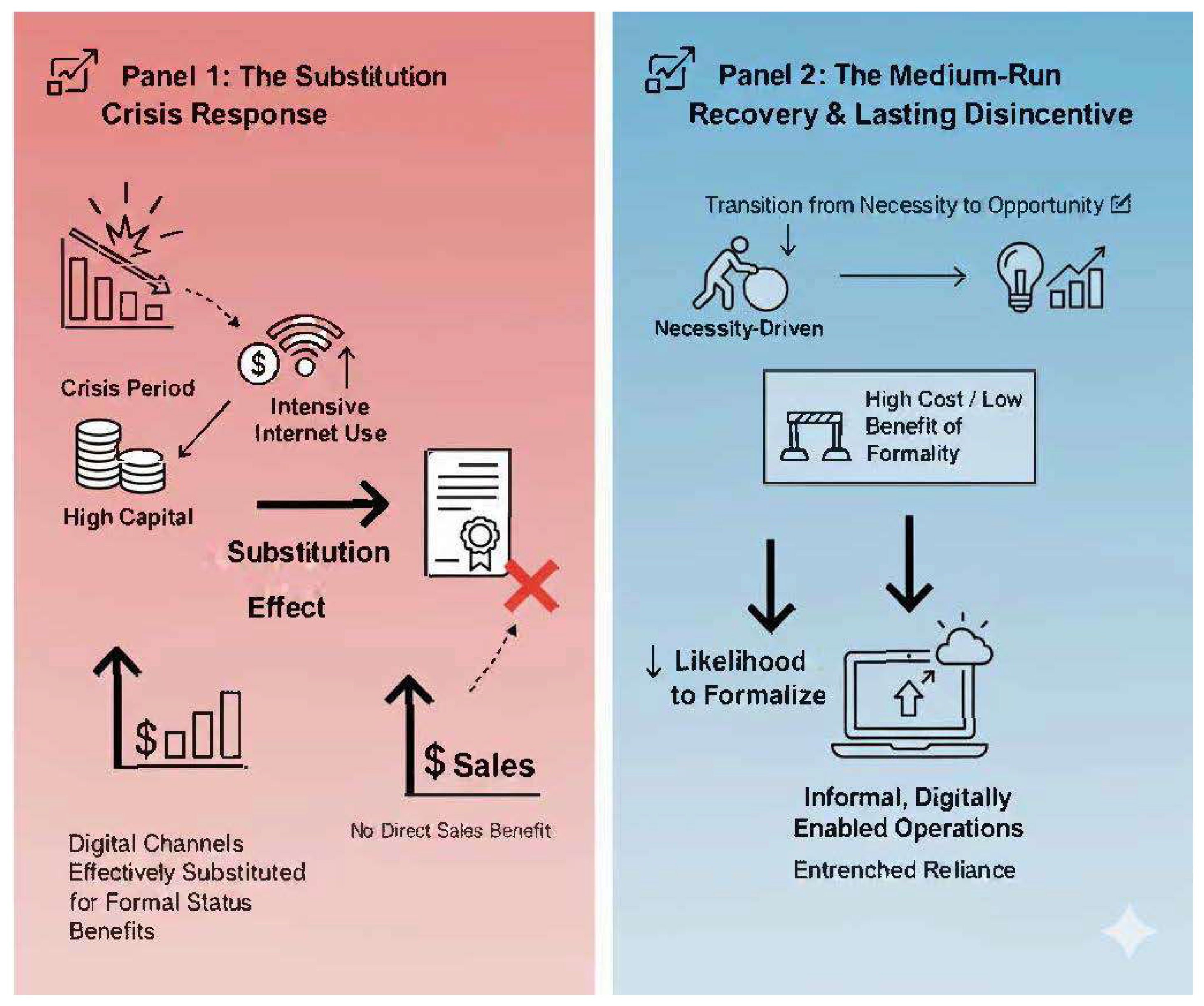

The pandemic-induced crisis triggered a short-run substitution mechanism, where the high fixed and variable costs of formality (like registration and permits) became binding. This was evidenced by new micro-entrepreneurs being predominantly necessity-driven (

Brixiová et al., 2020), characterized by low capital wealth and untrained status (

Estrin et al., 2024). These businesses achieved success by substituting slow formal processes with intensive Internet usage, which was a significant driver of sales growth (

Pawełoszeka et al., 2023;

Sagala & Őri, 2024;

Alshebami, 2025b). This survivalist nature (

Alshebami, 2025a) resulted in the counterintuitive finding that formal business registration was inversely associated with increased sales for the overall cohort, aligning with evidence from some emerging economies (

Jayachandran, 2021). The positive impact of capital wealth, staff, and accounting usage on sales, however, underscores the enduring value of traditional resources and managerial practices.

As economies transitioned into recovery, a distinct medium-run pattern in entrepreneurial motivation emerged. Opportunity-driven entrepreneurship, which is associated with better-resourced individuals—male, educated, higher capital wealth (

Estrin et al., 2024), gained share following the end of lockdowns. This rise signals the normalization of economic activity and the exploitation of new opportunities. However, this growth was not mirrored by family-driven entrepreneurship, which did not gain more share than necessity-driven ventures, thus challenging the notion that familial-resource-based entrepreneurship would necessarily thrive in the post-crisis environment (

Calabrò et al., 2021). Finally, the overall decline in business formalization in the post-pandemic period (

Alshebami, 2025a) suggests that many entrepreneurs preferred to retain the flexibility and lower costs of informality, indicating sustained uncertainty or insufficient incentives for formalization. A visual representation of these findings is presented in

Figure 4.

The above discussion highlights a clear gendered constraint mechanism where unpaid care time depressed formalization and lower-quantile sales. The necessity-driven profile was disproportionately female and burdened by a relatively higher share of unpaid working hours—a global trend exacerbated during the pandemic (

Ruiz-Martínez & Quiroz-Rojas, 2022;

Kan et al., 2022). This domestic resource-drain limited business growth, evidenced by the negative impact of unpaid work hours on sales at the 25th percentile for both genders. The resulting gender disparity showed that registration had a positive impact on sales only for men at higher quantiles, while having no discernible impact for women, who were likely concentrated in more informal, local business models tied to their constrained resources and domestic responsibilities (

Ruiz-Martínez & Quiroz-Rojas, 2022;

Brieger et al., 2023).

Nevertheless, one should bear in mind that this study is confined to two distinct periods: the short-run substitution mechanism triggered by the pandemic crisis and the medium-run pattern that emerged during the economic recovery. This temporal limitation means the findings may not apply to the long-term, post-recovery entrepreneurial landscape. The sustained effects of the shift to informality or the ultimate success rates of necessity- vs. opportunity-driven ventures over a longer horizon remain unaddressed. Furthermore, the study may be limited in its ability to disaggregate or prove the direct, structural mechanisms by which domestic burden translates into lower business formalization and depressed sales, beyond the simple correlation with unpaid hours.

6. Conclusions

Micro-entrepreneurship serves as a foundational element of the Chilean economy, fostering employment and contributing significantly to economic development. This article explored the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on micro-entrepreneurial activity within Chile, with particular emphasis on critical determinants such as business formality, capital endowment, educational attainment, and skills. The integration of a pre-pandemic analytical period enriched the study’s depth, facilitating a temporal comparison of entrepreneurial motivations and formalization trends. This methodological approach proved instrumental in isolating pandemic-specific effects from antecedent patterns.

Concurrently, evidence from other economies indicates that small- and medium-sized enterprises encountered substantial financial strain during the pandemic, thereby curtailing their capacity for investment in innovative initiatives (e.g.,

Bartik et al., 2020;

Fairlie, 2020;

Kuckertz et al., 2020;

Fairlie et al., 2023;

Alshebami, 2025b). Notably, U.S. data shows that small businesses were more likely to permanently close than larger enterprises during the nascent stages of the pandemic (

Fairlie et al., 2023). In turn a comprehensive study of small businesses for eight Latin American countries showed that the pandemic had large negative impacts on employment and beliefs regarding the future, and that government policy had limited impact for small and informal firms (

Guerrero-Amezaga et al., 2022).

6.1. Main Findings and Contributions

During the pandemic, increased sales correlated with higher levels of capital wealth, help from staff members, more intensive Internet usage, accounting usage, and working from home. In contrast, registering, obtaining a municipal permit, or running an established business reduced the odds of increasing sales. Furthermore, businesses offering services were less likely to increase their sales than those offering goods or products.

On the other hand, the role of domestic and caregiving responsibilities, especially during the pandemic, underscored the gendered nature of business constraints. For example, the number of unpaid hours had a greater negative impact on the likelihood of formalization for businesses led by women than for those led by men. Moreover, the decline in business formality after the pandemic, observed among both men and women, suggests a possible shift towards informal economic activities as people sought faster and less bureaucratic ways to adapt to the crisis. This trend may have been driven by increased barriers to formalization during the pandemic (e.g., administrative closures, financial constraints) and the need to generate immediate income.

In summary, this study contributed to existing literature by filling a notable research gap. Instead of focusing on large, established businesses, it provided an in-depth, longitudinal analysis of micro-entrepreneurs, a segment of the economy that is often overlooked but crucial for economic vitality in emerging economies. The research is particularly valuable because it offers geographically specific insights from Chile, a context that is not only understudied but also serves as a compelling case study for understanding how smaller economies respond to global crises.

By employing a novel and comprehensive analytical approach, the study moved beyond traditional economic models. It not only quantified the impact of various business strategies during the pandemic but also uncovered counterintuitive findings, such as the fact that business formality could hinder, rather than help, sales growth. This methodological design allowed the research to provide a more nuanced understanding of the factors that truly contribute to a micro-enterprise’s resilience. The focus on both informal and formal businesses, and its ability to track their evolution over time, provided a rich, data-driven narrative that challenged conventional wisdom and offered new directions for policy and future research.

6.2. Policy Implications

By implementing a combination of the following policies, governments can aim to foster a more resilient, inclusive, and growth-oriented micro-entrepreneurial sector, addressing both the immediate challenges highlighted by the pandemic and the longer-term structural issues.

- (i)

Policies to support sales growth and digitalization

Digitalization support programs: Implement initiatives that provide financial and technical assistance for micro-businesses to enhance their online presence. This could include subsidies for website development, e-commerce platform integration, digital marketing training, and access to affordable Internet services.

Capital injection and access to finance: Create accessible micro-loan or grant programs with simplified application processes to provide crucial capital for inventory, technology upgrades, and marketing efforts.

Promote the adoption of basic business tools: Offer training and subsidized access to user-friendly accounting software and digital management tools. This can help businesses better track finances, manage inventory, and make informed decisions.

Facilitate business networks and collaboration: Encourage the formation of online and offline networks that allow micro-businesses to share knowledge, resources, and potentially collaborate on marketing or distribution.

- (ii)

Policies addressing barriers to formalization

Streamlined registration and permitting processes: Simplify the processes for business registration and municipal permits by reducing bureaucratic hurdles and associated costs.

Temporary suspension or reduction in formalization fees: Consider temporary measures to waive or significantly reduce registration and permit fees, particularly for micro-businesses, to incentivize formalization during economic recovery.

Support for established businesses: Implement measures to alleviate the challenges faced by established businesses during crises. This could include tax breaks, access to credit lines, or tailored advisory services to help them adapt and avoid informalization.

- (iii)

Policies addressing gendered constraints

Caregiving support and flexible work arrangements: Explore policies that support working parents and caregivers, particularly women entrepreneurs. This could include subsidized childcare options, promotion of flexible work arrangements, and awareness campaigns to encourage a more equitable distribution of domestic responsibilities.

Targeted financial and training programs for women: Design specific programs that provide financial resources, business training, and mentorship tailored to the unique challenges faced by women entrepreneurs.

In that sense, Chile government’s National Support and Care Policy 2025–2030 aims at improving the well-being of caregivers and those in need of care. This is achieved through a 2025–2026 Action Plan with 100 measures developed jointly by various public agencies. In turn, the universal nursery project seeks to guarantee access to a nursery for all workers with children less than two years of age, regardless of their employment status.

- (iv)

Overall policy considerations

Data collection and monitoring: Implement robust data collection mechanisms to track the performance and challenges of micro-businesses, disaggregated by gender and formality status.

Coordination across government agencies: Ensure effective coordination between different government agencies involved in business registration, support programs, and social welfare to create a cohesive and supportive ecosystem for micro-entrepreneurs.

6.3. Future Research

A follow-up analysis could explore whether the decline in formality persisted after the pandemic or whether entrepreneurs returned to formality. Such an analysis could also investigate how the pandemic affected micro-enterprises in different industries, highlighting the different recovery pathways and challenges. Another aspect to consider would be the long-term effect of the pandemic on micro-enterprise activity, focusing on whether businesses that started out of necessity turned into opportunity-driven ventures.