How Ethical Behavior Is Considered in Different Contexts: A Bibliometric Analysis of Global Research Trends

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Ethical Behavior

2.2. Bibliometric

3. Methodology

4. Results

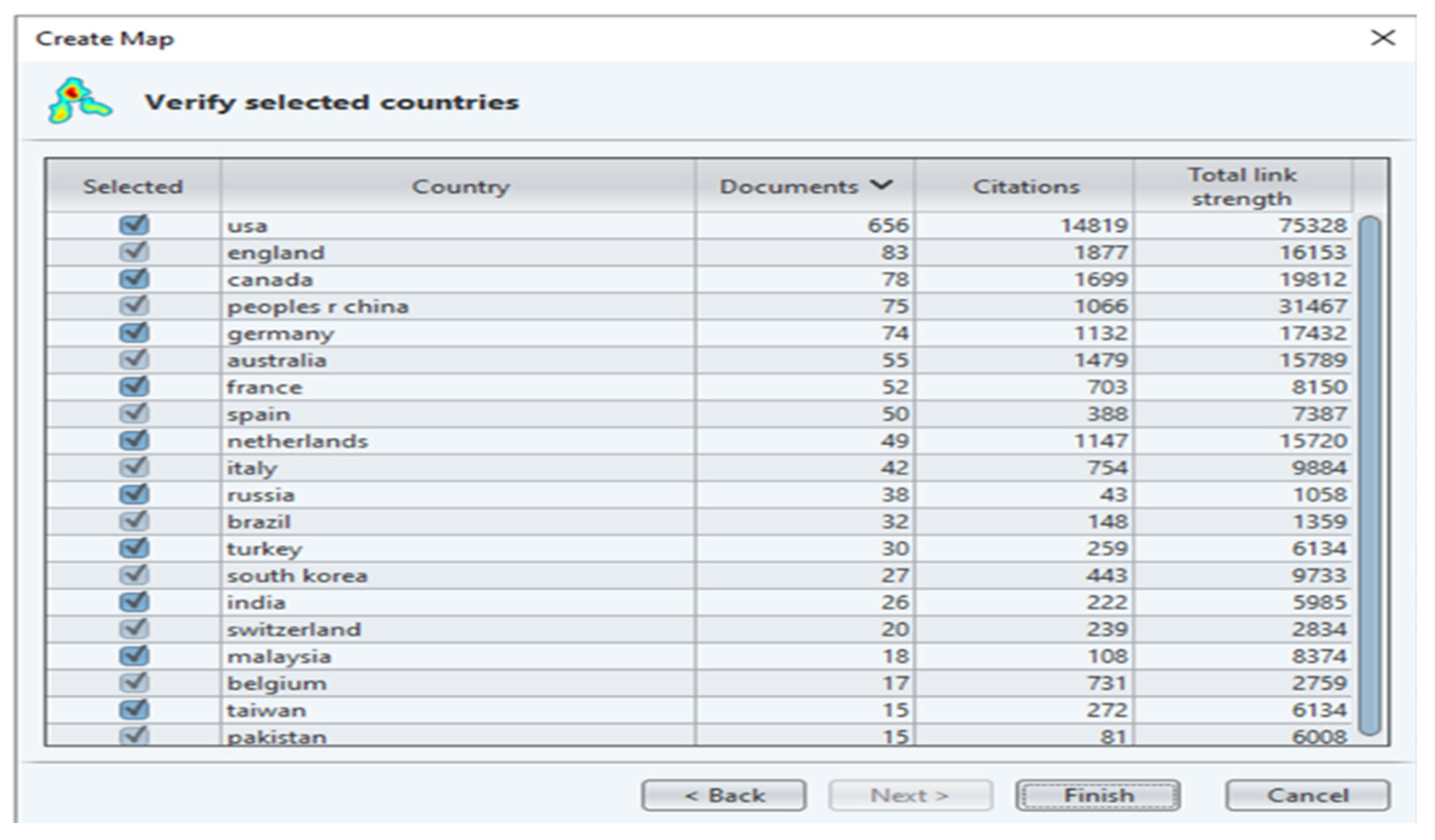

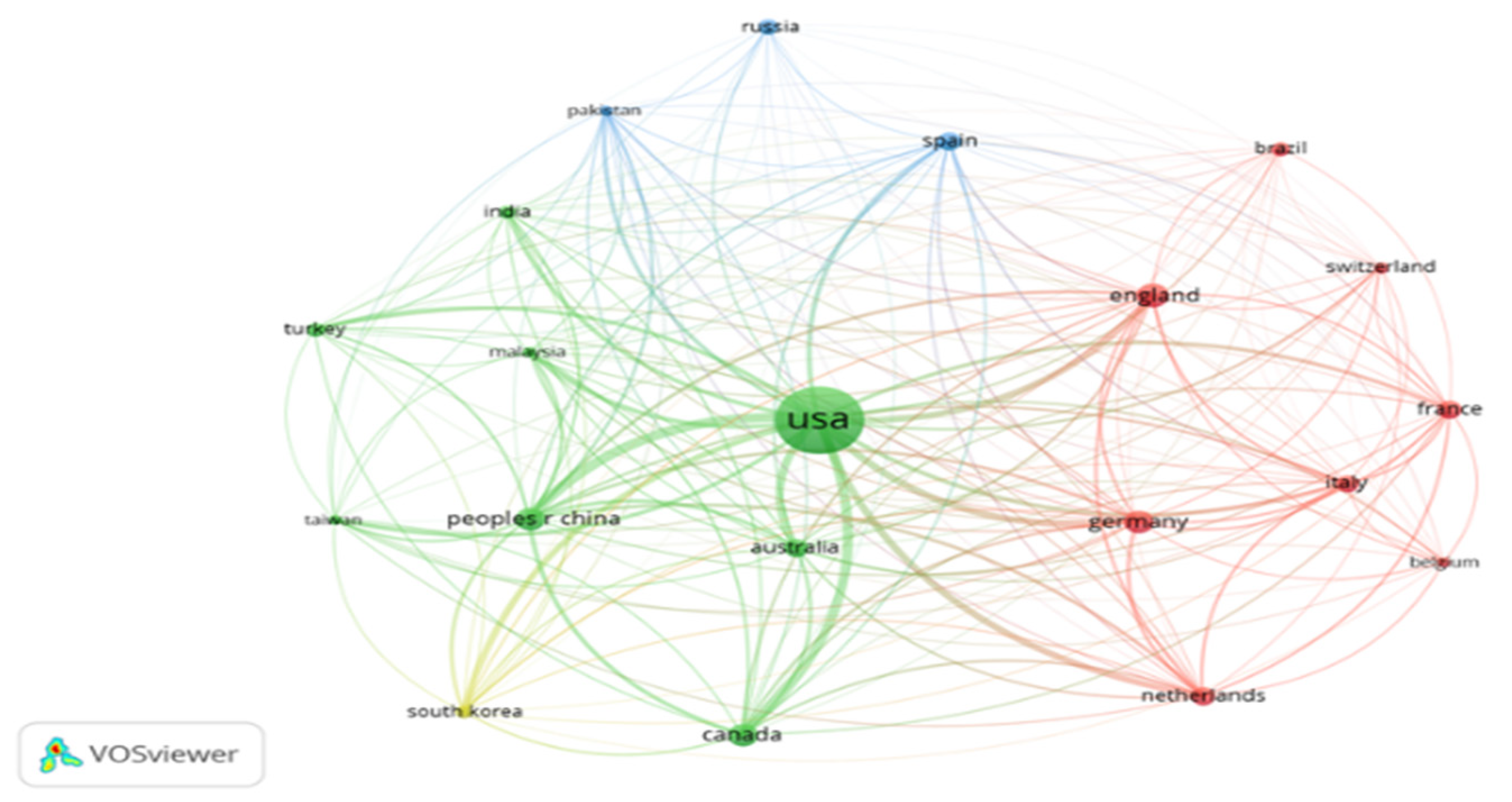

4.1. Countries and Their Concerns about Ethical Behavior

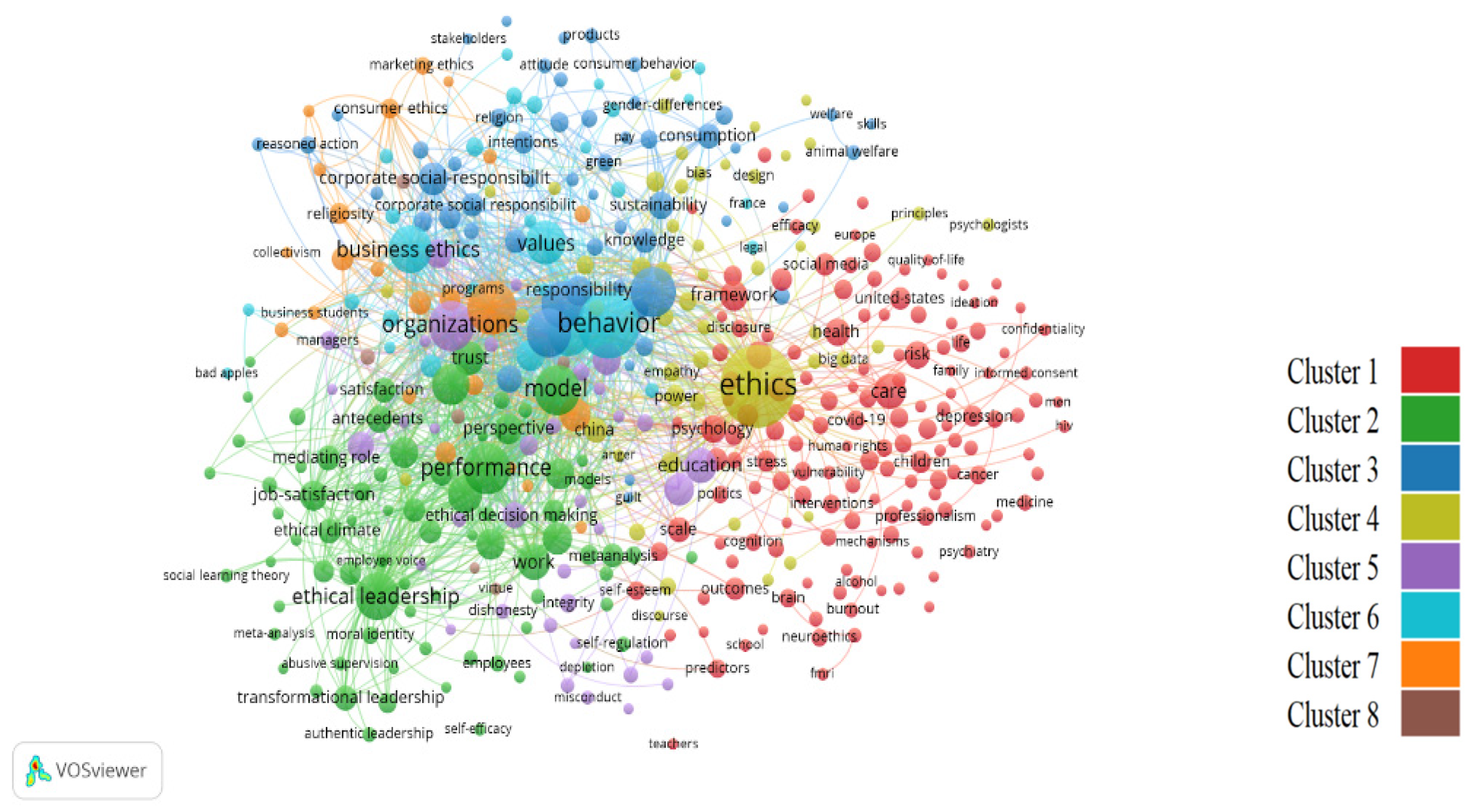

4.2. Key Themes in Research Terms

4.3. Bibliographic Coupling Analysis

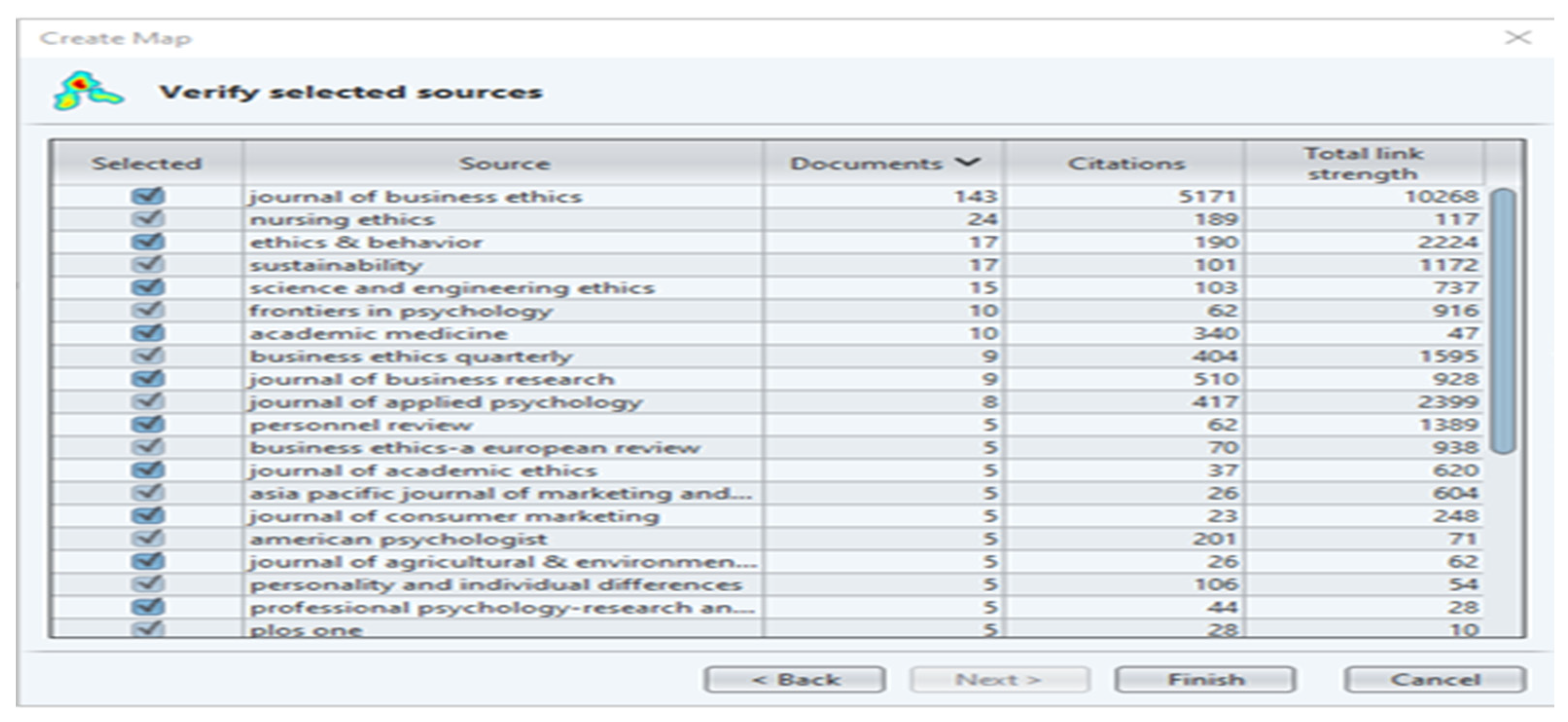

4.3.1. Journals

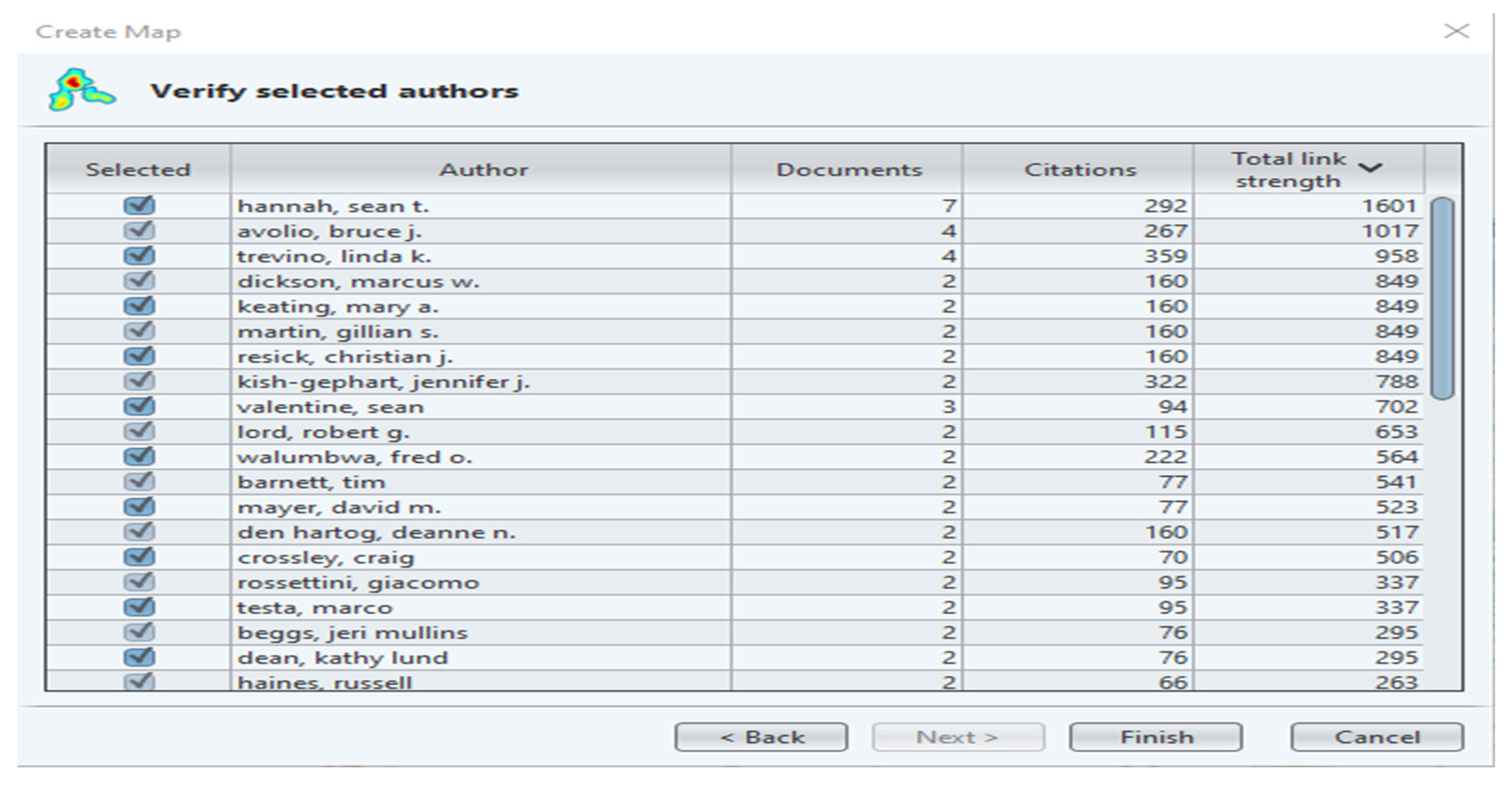

4.3.2. Authors

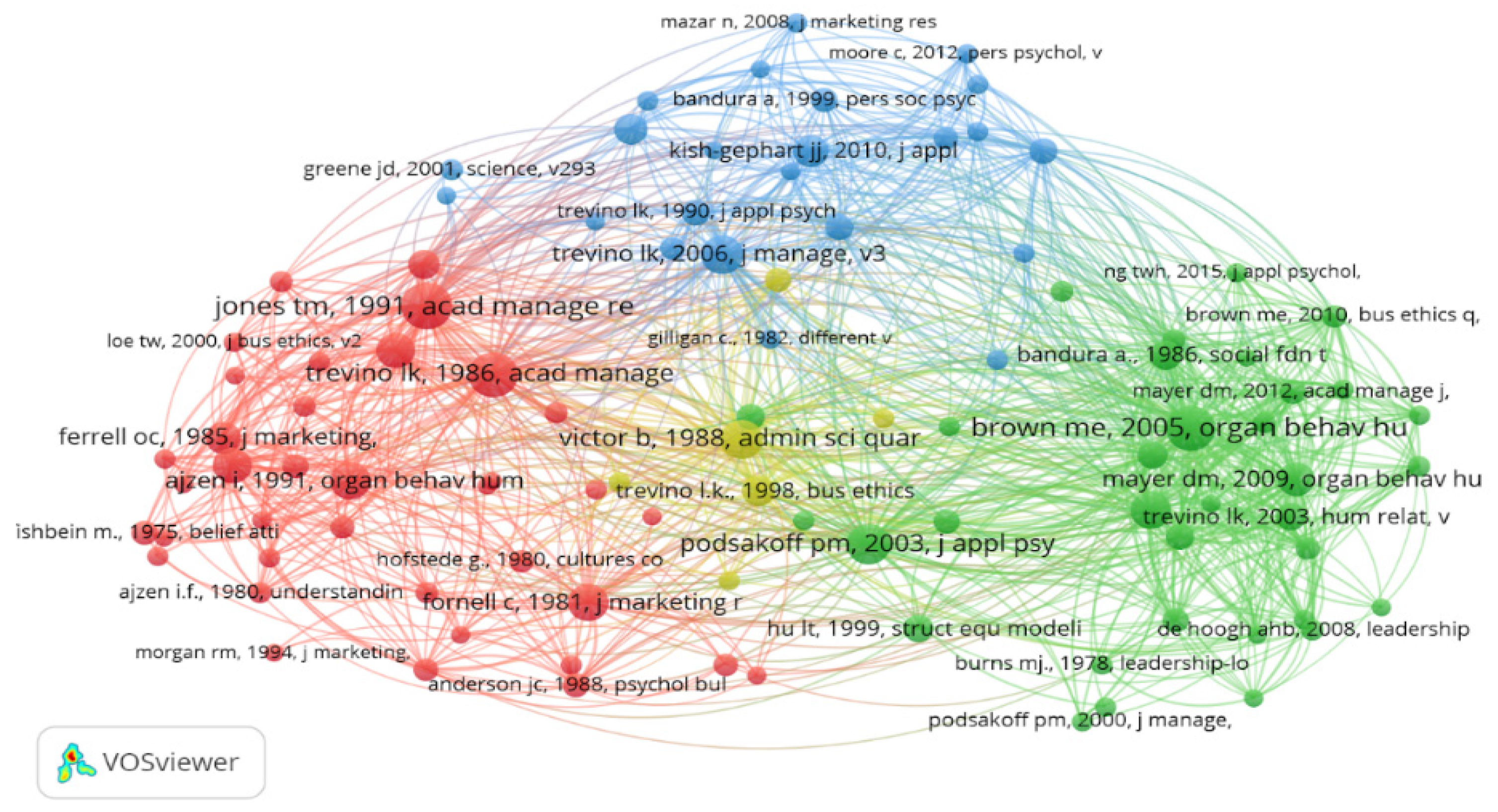

4.4. Co-Citation Analysis

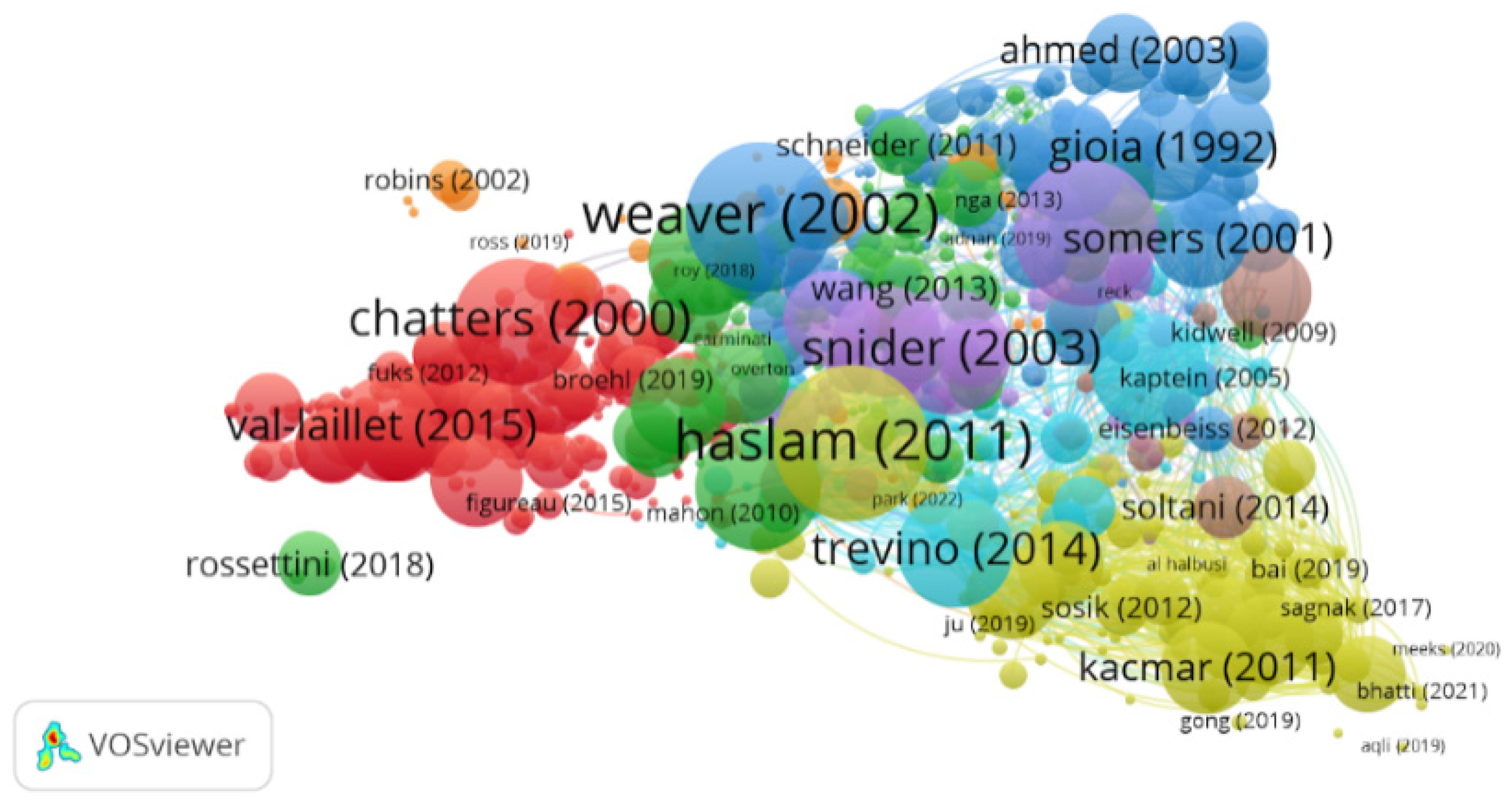

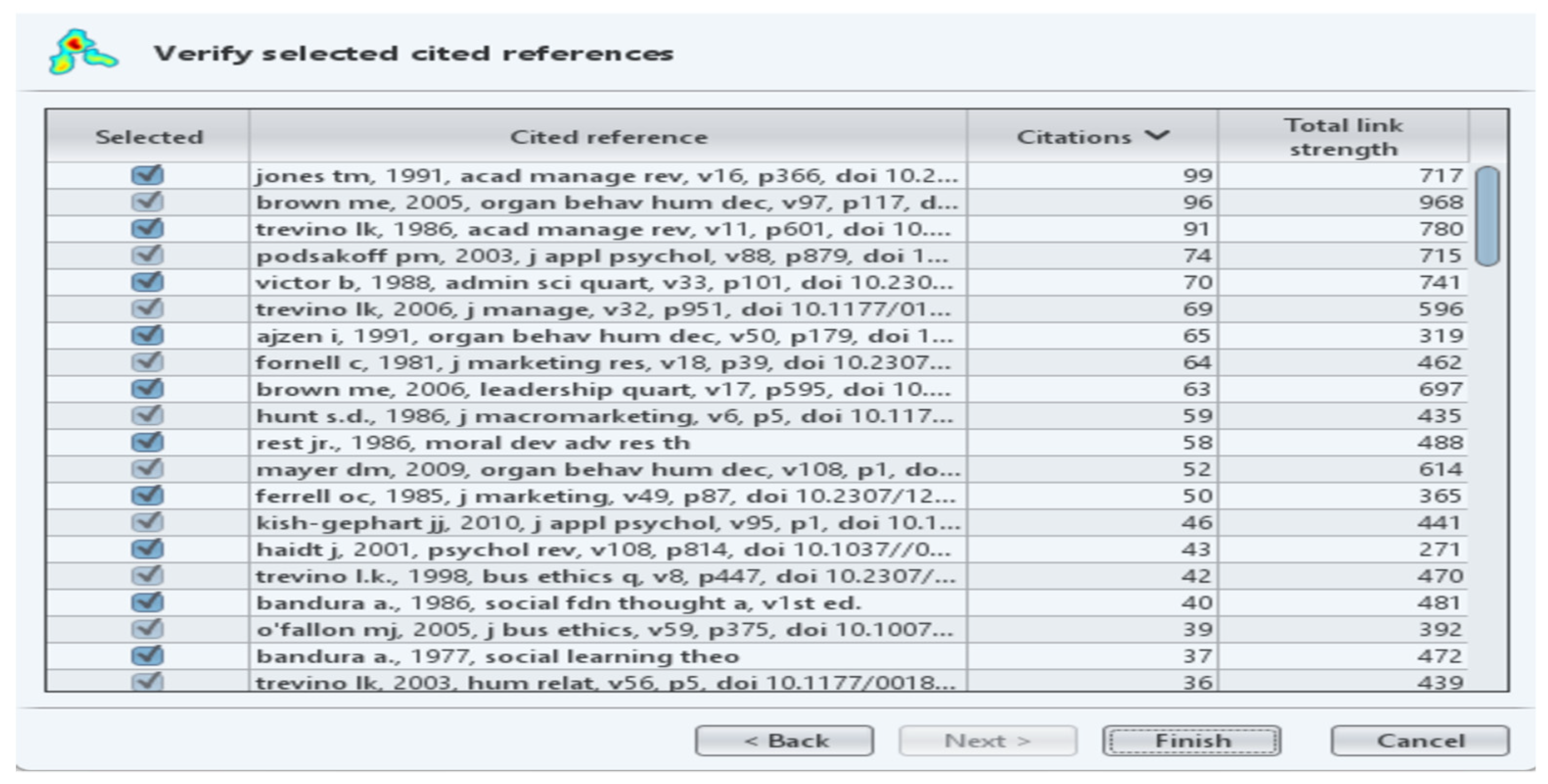

4.4.1. Publications

4.4.2. Journals

4.4.3. Authors

5. Discussion

5.1. Ethical Behavior in Consumption

5.2. Ethical Behavior in Leadership

5.2.1. Social Learning Theory (SLT)

5.2.2. Social Exchange Theory (SET)

Transformational Leadership

Authentic Leadership

Spiritual Leadership

5.3. Ethical Behavior in Business

- Focus on social responsibility;

- Emphasis on honesty and fairness;

- Focus on “Golden Rules”;

- Values that are consistent with a person’s behavior or religious beliefs;

- Obligations, responsibilities, and rights towards dedicated or enlightened work;

- Philosophy of good or bad;

- Ability to clarify issues in decision making;

- Focus on personal conscience;

- Systems or theories of justice that question the quality of one’s relationships;

- The relationship of the means to ends;

- Concern with integrity, what should be, habits, logic, and principles of Aristotle;

- Emphasis on virtue, leadership, confidentiality, judgment of others, putting God first, topicality, and publicity.

Values, Business Ethics, and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

5.4. Ethical Behavior in the Medical Context

5.4.1. Autonomy

5.4.2. Beneficence

5.4.3. Non-Maleficence

5.4.4. Fairness

5.5. Ethical Behaviour in Education

5.5.1. Violation of School/University Regulation

5.5.2. Selfishness

5.5.3. Cheating

5.5.4. Computer Ethics

5.6. Ethical Context in Organization

5.6.1. Context of Organizational Ethical Climate

5.6.2. Context of Organizational Ethical Culture

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Cluster | Author | Base | Concept |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1: Ethical Behavior in Organization and Business | Andreas Chatzidakis | Royal Holloway University | Ethical consumption |

| John Peloza | Kentucky University | Responsibility | |

| Sean Valentine | Louisiana Tech University | Ethical business, human management, and behavior in an organization | |

| Linda Treviño | Pennsylvania State University | Behavior in organizations and ethics, behavior in organizations and ethical business | |

| Gary R. Weaver | Delaware University | Moral awareness, ethical behavior in organizations | |

| Cluster 2: Ethical Behavior in Leadership | Bruce Avolio | Washington University | Ethical communication of leadership, strategic leadership from individual to global |

| Deanne N. Den Hartog | Amsterdam University | Leadership behavior in the organization, dynamic, international management | |

| Jennifer J. Kish-Gephart | Massachusetts—Amherst University | Behavioral ethics, diversity, social inequality, behavior, business ethics | |

| Fred O. Walumbwa | Arizona State University’s W.P. | Authentic leadership | |

| Cluster 3: Nervous, Deep Brain Stimulation, and Depression | Laura B. Dunn | Stanford University | Scientific and ethical issues related to deep brain stimulation for mood, behavioral, and thought disorders, ethics of schizophrenia, treatment of depression |

| Benjamin D. Greenberg | Brown University | Psychiatry, neuroscience, anxiety-related features, deep brain stimulation, treatment-resistant depression | |

| Joseph J. Fin | Rockefeller University, Weill Cornell Medical College | Consciousness disorders, deep brain stimulation, neurotechnology, neuroethics | |

| Thomas E. Schlaepfer | The Johns Hopkins University | Deep brain stimulation, depression, anxiety, neurobiology | |

| Cluster 4: Ethical Culture | Marcus Dickson Wayne | State University | Underlying leadership theories generalizing culture and multiculturalism, the influence of culture on leadership and organizations |

| Mary A. Keating | Trinity College Dublin | Multicultural management, ethics, human resource management | |

| Gillian S. Martin | College Dublin | Leadership culture change | |

| Christian Resick | Drexel University | Teamwork, personality, organizational culture and conformity, ethical leadership, and ethical-related organizational environment | |

| Cluster 5: Moral Psychology | Michael C. Gottieb and Mitchell M. Handelsman | The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center & University of Kansas | The Ethical Dilemma in Psychotherapy, Ethical Psychologist Training: A Self-Awareness Question for Effective Psychotherapists: Helping Good Psychotherapists Become Even Better, APA Handbook of Ethics in Psychology |

| Samuel L. Knapp | Dartmouth College | Physiological sustainability | |

| Cluster 6: Ethical issues in health care, especially concerned with the knowledge of nurses | Jang, In-sun | Sungshin Women’s University | Ethical decision-making model for nurses, nursing students, telehealth technology, research topics on family care between Korea and other countries |

| Park, Eun-jun | Sejong University | Nursing students, beliefs in knowledge and health, Korean nursing students, nurses’ organizational culture, health-related behavior |

| Cluster | Representative Author | Base | Concept |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1: Psychology, TPB, theory of the stages of moral development, the development of behavior in the context of makeup | Icek Ajzen | Massachusetts Amherst University | TPB |

| Shelby D. Hunt | Texas Technology University | Marketing research | |

| O.C. Ferrell | Auburn University | Ethical marketing, social responsibility | |

| Scott J. Vitell | Mississippi University | Business administration, social psychology, marketing, management | |

| Lawrence Kohlberg | Theory of the stages of moral development | ||

| AnusornSinghapakdi | Old Dominion University, Mississippi University | Marketing with subfields in consumer behavior and econometrics | |

| Cluster 2: Social cognitive theory, ethical behavior in leadership | Albert Bandura | Stanford University | Behaviorism and cognitive psychology, social learning theory originator, theoretical structure of self-efficacy |

| Michael E. Brown | Sam and Irene Black School of Business Penn State-Erie, The Behrend College | Behavioral leadership, ethics, ethical leadership, moral conflict | |

| David M. Mayer | Michigan University | Behavioral ethics, leadership ethics, organizational behavior | |

| Philip Podsakoff | Florida University | Citizen organization, behavioral organization, research methods leadership | |

| Cluster 3: Psychological, emotional, and unethical behavior | Francesca Gino | Harvard Business School | Unethical, dishonest behavior |

| Jonathan Haidt | NYU-Stern | Ethical psychology, political psychology, positive psychology, business ethics | |

| Ann E. Tenbrunsel | Notre Dame University | Psychology of ethical decision making and the ethical infrastructure in organizations, examining why employees, leaders, and students behave unethically, despite of their best intention | |

| Karl Aquino | British Columbia University | Ethics, forgiveness, victims, emotions. | |

| Cluster 4: Ethical behavior in business and organization | Theresa Jones | Ecological light pollution, chemical communication, immune function, history features, mating | |

| Linda Treviño | Pennsylvania State University | Organizational behavior and business ethics | |

| Gary R. Weaver | Delaware University | Behavioral ethics in organizations | |

| Bart Victor | Vanderbilt University | The organizational basis of an ethical work environment |

References

- Agrell, Anders, and Roland Gustafson. 1994. The Team Climate Inventory (TCI) and group innovation: A psychometric test on a Swedish sample of work groups. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 67: 143–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, Herman. 2011. Organizational responsibility: Doing good and doing well. In APA Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Edited by Sheldon Zedeck. Maintaining, Expanding, and Contracting the Organization. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, vol. 3, pp. 855–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Mohamed M., Kun Young Chung, and John W. Eichenseher. 2003. Business students’ perception of ethics and moral judgment: A cross-cultural study. Journal of Business Ethics 43: 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, Icek. 1991. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50: 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, Zafrul, Muzaffar Asad, Nasir Ali, and Azam Malik. 2022. Bibliometric analysis of research visualizations of knowledge aspects on burnout among teachers from 2012 to January 2022. Paper presented at the 2022 International Conference on Decision aid Sciences and Applications (DASA), Chiangrai, Thailand, March 23–25; pp. 126–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Library Association (ALA). 1983. ALA Glossary of Library and Information Science. Chicago: American Library Association. [Google Scholar]

- Aquino, Karl, and Americus Reed, II. 2002. The self-importance of moral identity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 83: 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arefeen, Sirajul, Mohammad E. Mohyuddin, and Mohammad Aktaruzzaman Khan. 2020. An exploration of unethical behavior attitude of tertiary level students of Bangladesh. Global Journal of Management and Business Research 20: 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arman, Saleh Md, and Cecilia Mark-Herbert. 2022. Ethical Pro-Environmental Self-Identity Practice: The Case of Second-Hand Products. Sustainability 14: 2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, Mary Beth, J. Edward Ketz, and Dwight Owsen. 2003. Ethics education in accounting: Moving toward ethical motivation and ethical behavior. Journal of Accounting Education 21: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaud, Anke, and Marshall Schminke. 2012. The ethical climate and context of organizations: A comprehensive model. Organization Science 23: 1767–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, Blake, Dennis A. Gioia, Sandra L. Robinson, and Linda K. Treviño. 2008. Re-viewing organizational corruption. Academy of Management Review 33: 670–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, Muhammad, Miao Qing, Jinsoo Hwang, and Hao Shi. 2019. Ethical leadership, affective commitment, work engagement, and creativity: Testing a multiple mediation approach. Sustainability 11: 4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, Hassan Danial, Sorinel Căpușneanu, Tasawar Javed, Ileana-Sorina Rakos, and Cristian-Marian Barbu. 2024. The mediating role of attitudes towards performing well between ethical leadership, technological innovation, and innovative performance. Administrative Sciences 14: 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, Bruce J., and William L. Gardner. 2005. Authentic leadership development: Getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. The Leadership Quarterly 16: 315–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, Bruce J., William L. Gardner, Fred O. Walumbwa, Fred Luthans, and Douglas R. May. 2004. Unlocking the mask: A look at the process by which authentic leaders impact follower attitudes and behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly 15: 801–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, Barry J., James S. Boles, and Donald P. Robin. 2000. Representing the perceived ethical work climate among marketing employees. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 28: 345–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Yuntao, Li Lin, and Joseph T. Liu. 2019. Leveraging the employee voice: A multi-level social learning perspective of ethical leadership. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 30: 1869–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Albert. 1977. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review 84: 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Albert. 1999. Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review 3: 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett, Tim, and Cheryl Vaicys. 2000. The moderating effect of individuals’ perceptions of ethical work climate on ethical judgments and behavioral intentions. Journal of Business Ethics 27: 351–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, Vincent. 1979. Moral Issues in Business. Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, Bernard M. 1985. Leadership and Performance Beyond Expectations. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Christopher W., and Linda J. Skitka. 2012. Corporate social responsibility as a source of employee satisfaction. Research in Organizational Behavior 32: 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, Vivianne, Inge van Nistelrooij, and Linus Vanlaere. 2017. The sensible health care professional: A care ethical perspective on the role of caregivers in emotionally turbulent practices. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy 20: 483–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, Tom L., and James F. Childress. 2001. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp, Tom L., and Norman E. Bowie. 1983. Ethical Theory and Business, 2nd ed. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudoin, Cathy A., Anna M. Cianci, Sean T. Hannah, and George T. Tsakumis. 2019. Bolstering managers’ resistance to temptation via the firm’s commitment to corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics 157: 303–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beciu, Silviu, Georgiana Armenița Arghiroiu, and Maria Bobeică. 2024. From Origins to Trends: A Bibliometric Examination of Ethical Food Consumption. Foods 13: 2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedi, Akanksha, Can M. Alpaslan, and Sandy Green. 2016. A meta-analytic review of ethical leadership outcomes and moderators. Journal of Business Ethics 139: 517–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benckendorff, Pierre, and Anita Zehrer. 2013. A network analysis of tourism research. Annals of Tourism Research 43: 121–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, Sabeen Hussain, Saifullah Khalid Kiyani, Scott B. Dust, and Ramsha Zakariya. 2021. The impact of ethical leadership on project success: The mediating role of trust and knowledge sharing. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business 14: 982–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bing, Mark N., H. Kristl Davison, Scott J. Vitell, Anthony P. Ammeter, Bart L. Garner, and Milorad M. Novicevic. 2012. An experimental investigation of an interactive model of academic cheating among business school students. Academy of Management Learning & Education 11: 28–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, Peter M. 1964. Exchange and Power in Social Life. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Broadus, Robert N. 1987. Toward a definition of “bibliometrics”. Scientometrics 12: 373–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Michael E., and Linda K. Treviño. 2006. Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. The leadership Quarterly 17: 595–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Michael E., and Marie S. Mitchell. 2010. Ethical and unethical leadership: Exploring new avenues for future research. Business Ethics Quarterly 20: 583–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Michael E., Linda K. Treviño, and David A. Harrison. 2005. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 97: 117–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunn, Douglas N., Steven B. Caudill, and Daniel M. Gropper. 1992. Crime in the classroom: An economic analysis of undergraduate student cheating behavior. The Journal of Economic Education 23: 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, James MacGregor. 1978. Leadership. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri, Mark Anthony. 2021. Strategic attributions of corporate social responsibility and environmental management: The business case for doing well by doing good! Sustainable Development 30: 409–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrington, Michal J., Ben Neville, and Robin Canniford. 2015. Unmanageable multiplicity: Consumer transformation towards moral self coherence. European Journal of Marketing 49: 1300–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, Archie B. 1991. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business Horizons 34: 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, Archie B. 2016. Carroll’s pyramid of CSR: Taking another look. International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility 1: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauffman, Elizabeth, S. Shirley Feldman, Lene Arnett Jensen, and Jeffrey Jensen Arnett. 2000. The (un) acceptability of violence against peers and dates. Journal of Adolescent Research 15: 652–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabowski, Brian R., Jeannette A. Mena, and Tracy L. Gonzalez-Padron. 2011. The structure of sustainability research in marketing, 1958–2008: A basis for future research opportunities. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 39: 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Yu-Wei, Mu-Hsuan Huang, and Chiao-Wen Lin. 2015. Evolution of research subjects in library and information science based on keyword, bibliographical coupling, and co-citation analyses. Scientometrics 105: 2071–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, Kenneth J., Richard Davis, Daniel Toy, and Lauren Wright. 2004. Academic integrity in the business school environment: I’ll get by with a little help from my friends. Journal of Marketing Education 26: 236–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatters, Linda M. 2000. Religion and health: Public health research and practice. Annual Review of Public Health 21: 335–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzidakis, Andreas, Pauline Maclaran, and Alan Bradshaw. 2012. Heterotopian space and the utopics of ethical and green consumption. Journal of Marketing Management 28: 494–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Wei-Fen, Xue Wang, Haiyan Gao, and Ying-Yi Hong. 2019. Understanding consumer ethics in China’s demographic shift and social reforms. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 31: 627–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Ziguang, Wing Lam, and Jian An Zhong. 2007. Leader-member exchange and member performance: A new look at individual-level negative feedback-seeking behavior and team-level empowerment climate. Journal of Applied Psychology 92: 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Erick H., and Joseph M. Pierre. 2015. The medical ethics of cognitive neuroenhancement. AIMS Neuroscience 2: 102–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Duncan, and Richie Unterberger. 2007. The Rough Guide to Shopping with a Conscience. New York: Rough Guides. [Google Scholar]

- Çollaku, Lum, Arbana Sahiti Ramushi, and Muhamet Aliu. 2024. Fraud intention and the relationship with selfishness: The mediating role of moral justification in the accounting profession. International Journal of Ethics and Systems, ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comoli, Maurizio, Patrizia Tettamanzi, and Michael Murgolo. 2023. Accounting for ‘ESG’ under Disruptions: A Systematic Literature Network Analysis. Sustainability 15: 6633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condon, Paul. 2019. Meditation in context: Factors that facilitate prosocial behavior. Current Opinion in Psychology 28: 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper-Martin, Elizabeth, and Morris B. Holbrook. 1993. Ethical consumption experiences and ethical space. Advances in Consumer Research 20: 113–18. [Google Scholar]

- Daradkeh, Mohammad. 2023. Navigating the complexity of entrepreneurial ethics: A Systematic review and future research agenda. Sustainability 15: 11099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasborough, Marie T., Sean T. Hannah, and Weichun Zhu. 2020. The generation and function of moral emotions in teams: An integrative review. Journal of Applied Psychology 105: 433–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hoogh, Annebel H. B., and Deanne N. Den Hartog. 2008. Ethical and despotic leadership, relationships with leader’s social responsibility, top management team effectiveness and subordinates’ optimism: A multi-method study. The Leadership Quarterly 19: 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Hoz-Correa, Andrea, Francisco Muñoz-Leiva, and Márta Bakucz. 2018. Past themes and future trends in medical tourism research: A co-word analysis. Tourism Management 65: 200–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeConinck, James B. 2011. The effects of ethical climate on organizational identification, supervisory trust, and turnover among salespeople. Journal of Business Research 64: 617–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nardo, Matteo, Anna Dalle Ore, Giuseppina Testa, Gail Annich, Edoardo Piervincenzi, Giorgio Zampini, Gabriella Bottari, Corrado Cecchetti, Antonio Amodeo, Roberto Lorusso, and et al. 2019. Principlism and personalism. Comparing two ethical models applied clinically in neonates undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support. Frontiers in Pediatrics 7: 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, Joerg, Sandra L. Robinson, Robert Folger, Robert A. Baron, and Martin Schulz. 2003. The impact of community violence and an organization’s procedural justice climate on workplace aggression. Academy of Management Journal 46: 317–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufresne, Ronald L. 2004. An action learning perspective on effective implementation of academic honor codes. Group & Organization Management 29: 201–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggan, Patrick S., Gail Geller, Lisa A. Cooper, and Mary Catherine Beach. 2006. The moral nature of patient-centeredness: Is it “just the right thing to do”. Patient Education and Counseling 62: 271–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellemers, Naomi, Stefano Pagliaro, Manuela Barreto, and Colin Wayne Leach. 2008. Is it better to be moral than smart? The effects of morality and competence norms on the decision to work at group status improvement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 95: 1397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelen, Bart. 2019. Ethical criteria for health-promoting nudges: A case-by-case analysis. The American Journal of Bioethics 19: 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erokhin, Vasilii, Kamel Mouloudj, Ahmed C. Bouarar, Smail Mouloudj, and Tianming Gao. 2024. Investigating Farmers’ Intentions to Reduce Water Waste through Water-Smart Farming Technologies. Sustainability 16: 4638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Guanhua, Zhenhua Lin, Yizhen Luo, Maohuai Chen, and Liping Li. 2019. Role of community health service programs in navigating the medical ethical slippery slope—A 10-year retrospective study among medical students from southern China. BMC Medical Education 19: 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, Karine Araújo, Larissa Almeida Flávio, and Lasara Fabrícia Rodrigues. 2018. Postponement: Bibliometric analysis and systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Logistics Systems and Management 30: 69–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, Odies C., and Larry G. Gresham. 1985. A contingency framework for understanding ethical decision making in marketing. Journal of Marketing 49: 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, R. H. George, and Michael A. Abelson. 1982. Climate: A reconceptualization and proposed model. Human Relations 35: 181–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, Martin, and Icek Ajzen. 1977. Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Philosophy and Rhetoric 10: 130–32. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, Claes, and David F. Larcker. 1981. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research 18: 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, William C. 1960. The growing concern over business responsibility. California Management Review 2: 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friend, Scott B., Fernando Jaramillo, and Jeff S. Johnson. 2020. Ethical climate at the frontline: A meta-analytic evaluation. Journal of Service Research 23: 116–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, Louis W. 2003. Toward a theory of spiritual leadership. The Leadership Quarterly 14: 693–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamarra, María Pilar, and Michele Girotto. 2022. Ethical behavior in leadership: A bibliometric review of the last three decades. Ethics & Behavior 32: 124–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatersleben, Birgitta, Niamh Murtagh, Megan Cherry, and Megan Watkins. 2019. Moral, wasteful, frugal, or thrifty? Identifying consumer identities to understand and manage pro-environmental behavior. Environment and Behavior 51: 24–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goebel, Sebastian, and Barbara E. Weißenberger. 2017. The relationship between informal controls, ethical work climates, and organizational performance. Journal of Business Ethics 141: 505–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, Melody A. 1994. Cheating at small colleges: An examination of student and faculty attitudes and behaviors. Journal of College Student Development 35: 255–60. [Google Scholar]

- Gram-Hanssen, Kirsten. 2021. Conceptualising ethical consumption within theories of practice. Journal of Consumer Culture 21: 432–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, Joshua D., Brian Sommerville, Leigh E. Nystrom, John M. Darley, and Jonathan D. Cohen. 2001. An fMRI investigation of emotional engagement in moral judgment. Science 293: 2105–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenleaf, Robert K. 2002. Servant Leadership: A Journey into the Nature of Legitimate Power and Greatness. Mahwah: Paulist Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory-Smith, Diana, Danae Manika, and Pelin Demirel. 2017. Green intentions under the blue flag: Exploring differences in EU consumers’ willingness to pay more for environmentally-friendly products. Business Ethics: A European Review 26: 205–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobler, Sonja, and Anton Grobler. 2021. Ethical leadership, person-organizational fit, and productive energy: A South African sectoral comparative study. Ethics & Behavior 31: 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidt, Jonathan. 2001. The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological Review 108: 814–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haines, Russell, and Lori N. K. Leonard. 2007. Individual characteristics and ethical decision-making in an IT context. Industrial Management & Data Systems 107: 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, Trevor S., Matthew J. Mayhew, Cynthia J. Finelli, and Donald D. Carpenter. 2007. The Theory of Planned Behavior as a Model of Academic Dishonesty in Engineering and Humanities Undergraduates. Ethics & Behavior 17: 255–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, Rob, Terry Newholm, and Deirdre Shaw. 2005. The Ethical Consumer. New York: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, Paul, Mark J. Martinko, and Nancy Borkowski. 2017. Justifying deviant behavior: The role of attributions and moral emotions. Journal of Business Ethics 141: 779–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Louise M., Edward Shiu, and Deirdre Shaw. 2016. Who says there is an intention–behaviour gap? Assessing the empirical evidence of an intention–behaviour gap in ethical consumption. Journal of Business Ethics 136: 219–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirth-Goebel, Tabea Franziska, and Barbara E. Weißenberger. 2019. Management accountants and ethical dilemmas: How to promote ethical intention? Journal of Management Control 30: 287–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, David A., and Barbara Mark. 2006. An investigation of the relationship between safety climate and medication errors as well as other nurse and patient outcomes. Personnel Psychology 59: 847–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Eun-Sil, and Hyo-Yeon Shin. 2010. Ethical consumption and related variables of college students. Korean Journal of Family Management 13: 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Yeon Geum, and Insook Song. 2008. A study of cases of ethical consumption in the analysis of purchasing motives of environmentally-friendly agriculture products. Journal of Consumption Culture 11: 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Wen-yeh, Ching-Yun Huang, and Alan J. Dubinsky. 2014. The impact of guanxi on ethical perceptions: The case of Taiwanese salespeople. Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing 21: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, Shelby D., and Scott Vitell. 1986. A general theory of marketing ethics. Journal of Macromarketing 6: 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husser, Jocelyn, Jean-Marc Andre, and Véronique Lespinet-Najib. 2019. The impact of locus of control, moral intensity, and the microsocial ethical environment on purchasing-related ethical reasoning. Journal of Business Ethics 154: 243–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Kevin J., Joé T. Martineau, Saouré Kouamé, Gokhan Turgut, and Serge Poisson-de-Haro. 2018. On the unethical use of privileged information in strategic decision-making: The effects of peers’ ethicality, perceived cohesion, and team performance. Journal of Business Ethics 152: 917–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Olivia, and Veena Chattaraman. 2019. Conceptualization and measurement of millennial’s social signaling and self-signaling for socially responsible consumption. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 18: 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Thomas M. 1991. Ethical decision making by individuals in organizations: An issue-contingent model. Academy of Management Review 16: 366–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacmar, Kacmar, K. Michele, Daniel G. Bachrach, Kenneth J. Harris, and Suzanne Zivnuska. 2011. Fostering good citizenship through ethical leadership: Exploring the moderating role of gender and organizational politics. Journal of Applied Psychology 96: 633–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Jee-Won, and Young Namkung. 2018. The effect of corporate social responsibility on brand equity and the moderating role of ethical consumerism: The case of Starbucks. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research 42: 1130–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanungo, Rabindra N. 2001. Ethical values of transactional and transformational leaders. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences 18: 257–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautish, Pradeep, Justin Paul, and Rajesh Sharma. 2019. The moderating influence of environmental consciousness and recycling intentions on green purchase behavior. Journal of Cleaner Production 228: 1425–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keck, Natalija, Steffen R. Giessner, Niels Van Quaquebeke, and Erica Kruijff. 2020. When do followers perceive their leaders as ethical? A relational models perspective of normatively appropriate conduct. Journal of Business Ethics 164: 477–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, Paul, Simon J. Marshall, Hannah Badland, Jacqueline Kerr, Melody Oliver, Aiden R. Doherty, and Charlie Foster. 2013. An ethical framework for automated, wearable cameras in health behavior research. American journal of Preventive Medicine 44: 314–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelman, Herbert C., and V. Lee Hamilton. 1989. Crimes of Obedience: Toward a Social Psychology of Authority and Responsibility. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kerse, Gökhan. 2021. A leader indeed is a leader in deed: The relationship of ethical leadership, person–organization fit, organizational trust, and extra-role service behavior. Journal of Management & Organization 27: 601–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Hyelin Lina, Yinyoung Rhou, Muzaffer Uysal, and Nakyung Kwon. 2017. An examination of the links between corporate social responsibility (CSR) and its internal consequences. International Journal of Hospitality Management 61: 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Junghwan, and Mei-Po Kwan. 2021. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people’s mobility: A longitudinal study of the US from March to September of 2020. Journal of Transport Geography 93: 103039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Jungsun Sunny, Hak Jun Song, and Choong-Ki Lee. 2016. Effects of corporate social responsibility and internal marketing on organizational commitment and turnover intentions. International Journal of Hospitality Management 55: 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsch, Roxanne E., Corrine R. Balit, Franco A. Carnevale, Jos M. Latour, and Victor Larcher. 2018. Ethical, cultural, social, and individual considerations prior to transition to limitation or withdrawal of life-sustaining therapies. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine 19: 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirsch, Roxanne, and David Munson. 2018. Ethical and end of life considerations for neonates requiring ECMO support. Seminars in Perinatology 42: 129–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, Katherine J., and Joann Speer Sorra. 1996. The challenge of innovation implementation. Academy of Management Review 21: 1055–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlberg, Lawrence. 1976. Moral stages and moralization: The cognitive-development approach. In Moral Development and Behavior: Theory and Research and Social Issues. Edited by Thomas Lickona. New York: Holt, Rienhart, and Winston, pp. 31–53. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlberg, Lawrence. 1981. The Philosophy of Moral Development: Moral Stages and the Idea of Justice. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Köseoglu, Mehmet Ali, Yasin Sehitoglu, Gary Ross, and John A. Parnell. 2016. The evolution of business ethics research in the realm of tourism and hospitality: A bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 28: 1598–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laratta, Rosario. 2011. Ethical climate and accountability in nonprofit organizations: A comparative study between Japan and the UK. Public Management Review 13: 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, Dana J. 2007. The four principles of biomedical ethics: A foundation for current bioethical debate. Journal of Chiropractic Humanities 14: 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, Xi Y., Jie Sun, and Billy Bai. 2017. Bibliometrics of social media research: A co-citation and co-word analysis. International Journal of Hospitality Management 66: 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Phillip V. 1985. Defining ‘business ethics’: Like nailing jello to a wall. Journal of Business Ethics 4: 377–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Hui, and Deborah E. Rupp. 2005. The impact of justice climate and justice orientation on work outcomes: A cross-level multifoci framework. Journal of Applied Psychology 90: 242–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Yongdan, Matthew Tingchi Liu, Andrea Pérez, Wilco Chan, Jesús Collado, and Ziying Mo. 2020. The importance of knowledge and trust for ethical fashion consumption. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 33: 1154–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, Fred, and Bruce J. Avolio. 2003. Authentic leadership: A positive developmental approach. In Positive Organizational Scholarship. Edited by Kim S. Cameron, Jane E. Dutton and Robert E. Quinn. San Francisco: Barrett-Koehler, pp. 241–61. [Google Scholar]

- Machlup, Fritz, and Una Mansfield. 1983. Cultural Diversity in Studies of Information. In The Study of Information: Interdisciplinary Messages. Edited by F. Machlup and U. Mansfield. New York: John Wiley and Sons, pp. 3–59. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Sean R., Jennifer J. Kish-Gephart, and James R. Detert. 2014. Blind forces: Ethical infrastructures and moral disengagement in organizations. Organizational Psychology Review 4: 295–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas-Tur, Alicia, Norat Roig-Tierno, Shikhar Sarin, Christophe Haon, Trina Sego, Mustapha Belkhouja, Alan Porter, and José M. Merigó. 2021. Co-citation, bibliographic coupling and leading authors, institutions and countries in the 50 years of Technological Forecasting and Social Change. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 165: 120487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, Douglas R., Young K. Chang, and Ruodan Shao. 2015. Does ethical membership matter? Moral identification and its organizational implications. Journal of Applied Psychology 100: 681–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, David M. 2014. A review of the literature on ethical climate and culture. In The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Climate and Culture. Edited by Benjamin Schneider and Karen M. Barbera. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 415–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, David M., Maribeth Kuenzi, Rebecca Greenbaum, Mary Bardes, and Rommel (Bombie) Salvador. 2009. How low does ethical leadership flow? Test of a trickle-down model. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 108: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazar, Nina, On Amir, and Dan Ariely. 2008. The dishonesty of honest people: A theory of self-concept maintenance. Journal of Marketing Research 45: 633–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCain, Katherine W. 1990. Mapping authors in intellectual space: A technical overview. Journal of the American Society for Information Science (1986–1996) 41: 433–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, Joseph W. 1963. Factors Affecting the Growth of Manufacturing Firms. Seattle: University of Washington, Bureau of Business Research. [Google Scholar]

- McKay, Patrick F., Derek R. Avery, and Mark A. Morris. 2009. “A tale of two climates: Diversity climate from subordinates” and managers’ perspectives and their role in store unit sales performance. Personnel Psychology 62: 767–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurtry, Kim. 2001. E-cheating: Combating a 21st Century challenge. T.H.E. Journal 29: 36–38. [Google Scholar]

- Mihelič, Katarina Katja, and Barbara Culiberg. 2014. Turning a blind eye: A study of peer reporting in a business school setting. Ethics & Behavior 24: 364–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, Marie S., Scott J. Reynolds, and Linda K. Treviño. 2020. The study of behavioral ethics within organizations: A special issue introduction. Personnel Psychology 73: 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohi Ud Din, Qaiser, and Li Zhang. 2023. Unveiling the mechanisms through which leader integrity shapes ethical leadership behavior: Theory of planned behavior perspective. Behavioral Sciences 13: 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, Celia, David M. Mayer, Flora F. T. Chiang, Craig Crossley, Matthew J. Karlesky, and Thomas A. Birtch. 2019. Leaders matter morally: The role of ethical leadership in shaping employee moral cognition and misconduct. Journal of Applied Psychology 104: 123–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouloudj, Kamel, and Ahmed Chemseddine Bouarar. 2023. Investigating predictors of medical students’ intentions to engagement in volunteering during the health crisis. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies 14: 205–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouloudj, Kamel, Anuli Njoku, Dachel Martínez Asanza, Ahmed Chemseddine Bouarar, Marian A. Evans, Smail Mouloudj, and Achouak Bouarar. 2023. Modeling Predictors of Medication Waste Reduction Intention in Algeria: Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20: 6584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulki, Jay Prakash, Fernando Jaramillo, Shavin Malhotra, and William B. Locander. 2012. Reluctant employees and felt stress: The moderating impact of manager decisiveness. Journal of Business Research 65: 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumford, Michael D., Ginamarie M Scott, Blaine Gaddis, and Jill M Strange. 2002. Leading creative people: Orchestrating expertise and relationships. The Leadership Quarterly 13: 705–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murrell, Vicki S. 2014. The failure of medical education to develop moral reasoning in medical students. International Journal of Medical Education 5: 219–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathanson, Craig, Delroy L. Paulhus, and Kevin M. Williams. 2006. Predictors of a behavioral measure of scholastic cheating: Personality and competence but not demographics. Contemporary Educational Psychology 31: 97–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nga, Joyce K. H., and Evelyn W. S. Lum. 2013. An investigation into unethical behavior intentions among undergraduate students: A Malaysian study. Journal of Academic Ethics 11: 45–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoku, Anuli, Kamel Mouloudj, Ahmed Chemseddine Bouarar, Marian A. Evans, Dachel Martínez Asanza, Smail Mouloudj, and Achouak Bouarar. 2024. Intentions to create green start-ups for collection of unwanted drugs: An empirical study. Sustainability 16: 2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, Yoon Goo, and Se Young Kim. 2024. Factors of hospital ethical climate among hospital nurses in Korea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Healthcare 12: 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onesti, Gianni. 2023. Exploring the impact of leadership styles, ethical behavior, and organizational identification on workers’ well-being. Administrative Sciences 13: 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellano, Anabel, Carmen Valor, and Emilio Chuvieco. 2020. The Influence of Religion on Sustainable Consumption: A Systematic Review and Future Research Agenda. Sustainability 12: 7901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overall, Jeffrey, and Steven Gedeon. 2023. Rational Egoism virtue-based ethical beliefs and subjective happiness: An empirical investigation. Philosophy of Management 22: 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Yue, and John R. Sparks. 2012. Predictors, consequence, and measurement of ethical judgments: Review and meta-analysis. Journal of Business Research 65: 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepper, Miriam, Tim Jackson, and David Uzzell. 2009. An examination of the values that motivate socially conscious and frugal consumer behaviours. International Journal of Consumer Studies 33: 126–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovskaya, Irina, and Fazli Haleem. 2021. Socially responsible consumption in Russia: Testing the theory of planned behavior and the moderating role of trust. Business Ethics, the Environment & Responsibility 30: 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolo, Ronald F., Rebecca Greenbaum, Deanne N. den Hartog, and Robert Folger. 2010. The relationship between ethical leadership and core job characteristics. Journal of Organizational Behavior 31: 259–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, Philip M., Scott B. MacKenzie, Jeong-Yeon Lee, and Nathan P. Podsakoff. 2003. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology 88: 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, William Gray. 1981. Introduction to bibliometrics. Library Trends 30: 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Rasool, Shahid, Roberto Cerchione, and Jari Salo. 2020. Assessing ethical consumer behavior for sustainable development: The mediating role of brand attachment. Sustainable Development 28: 1620–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reave, Laura. 2005. Spiritual values and practices related to leadership effectiveness. The Leadership Quarterly 16: 655–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resick, Christian J., Gillian S. Martin, Mary A. Keating, Marcus W. Dickson, Ho Kwong Kwan, and Chunyan Peng. 2011. What ethical leadership means to me: Asian, American, and European perspectives. Journal of Business Ethics 101: 435–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rest, James R. 1986. Moral Development: Advances in Research and Theory. New York: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Rey-Martí, Andrea, Domingo Ribeiro-Soriano, and Daniel Palacios-Marqués. 2016. A bibliometric analysis of social entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Research 69: 1651–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, Hettie A., and Robert J. Vandenberg. 2005. Integrating managerial perceptions and transformational leadership into a work-unit level model of employee involvement. Journal of Organizational Behavior 26: 561–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, James A. 1993. Sex differences in socially responsible consumers’ behavior. Psychological Reports 73: 139–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, Christopher J. 2008. An analysis of 10 years of business ethics research in strategic management journal: 1996–2005. Journal of Business Ethics 80: 745–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Rad, Carlos. J., and Encarnacion Ramos-Hidalgo. 2018. Spirituality, consumer ethics, and sustainability: The mediating role of moral identity. Journal of Consumer Marketing 35: 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romani, Simona, Silvia Grappi, and Richard P. Bagozzi. 2016. Corporate socially responsible initiatives and their effects on consumption of green products. Journal of Business Ethics 135: 253–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, Michael W. 2005. Typing, doing, and being: Sexuality and the Internet. Journal of Sex Research 42: 342–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, Achinto, Alexander Newman, Heather Round, and Sukanto Bhattacharya. 2024. Ethical culture in organizations: A review and agenda for future research. Business Ethics Quarterly 34: 97–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runes, Dagobert D. 1964. Dictionary of Philosophy. Patterson: Littlefields, Adams and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Saini, Supreet. 2013. Academic ethics at the undergraduate level: Case study from the formative years of the institute. Journal of Academic Ethics 11: 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-González, Irene, Irene Gil-Saura, and María Eugenia Ruiz-Molina. 2020. Ethically Minded Consumer Behavior, Retailers’ Commitment to Sustainable Development, and Store Equity in Hypermarkets. Sustainability 12: 8041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schminke, Marshall, Anke Arnaud, and Maribeth Kuenzi. 2007. The power of ethical work climates. Organizational Dynamics 36: 171–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwepker, Charles H., Jr. 2001. Ethical climate’s relationship to job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and turnover intention in the salesforce. Journal of Business Research 54: 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şendağ, Serkan, Mesut Duran, and M. Robert Fraser. 2012. Surveying the extent of involvement in online academic dishonesty (e-dishonesty) related practices among university students and the rationale students provide: One university’s experience. Computers in Human Behavior 28: 849–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapira-Lishchinsky, Orly, and Zehava Rosenblatt. 2010. School ethical climate and teachers’ voluntary absence. Journal of Educational Administration 48: 164–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhapakdi, Anusorn. 1993. Ethical perceptions of marketers: The interaction effects of Machiavellianism and organizational ethical culture. Journal of Business Ethics 12: 407–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Samantha, and Angela Paladino. 2010. Eating clean and green? Investigating consumer motivations towards the purchase of organic food. Australasian Marketing Journal 18: 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snider, Jamie, Ronald Paul Hill, and Diane Martin. 2003. Corporate social responsibility in the 21st century: A view from the world’s most successful firms. Journal of Business Ethics 48: 175–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler-Costa, Rebeca, Pablo Lafarga-Ostáriz, Marta Mauri-Medrano, and Antonio-José Moreno-Guerrero. 2021. Netiquette: Ethic, Education, and Behavior on Internet—A Systematic Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soltani, Bahram. 2014. The anatomy of corporate fraud: A comparative analysis of high profile American and European corporate scandals. Journal of Business Ethics 120: 251–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starr, Martha A. 2009. The social economics of ethical consumption: Theoretical considerations and empirical evidence. The Journal of Socio-Economics 38: 916–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, Paul C., Thomas Dietz, and Gregory A. Guagnano. 1995. The new ecological paradigm in social-psychological context. Environment and Behavior 27: 723–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Hsin-Ning, and Pei-Chun Lee. 2010. Mapping knowledge structure by keyword co-occurrence: A first look at journal papers in Technology Foresight. Scientometrics 85: 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumanth, John J., and Sean T. Hannah. 2014. An Integration and Exploration of Ethical and Authentic Leadership Antecedents. In Advances in Authentic and Ethical Leadership. Edited by Linda L. Neider and Chester A. Schriesheim. Charlotte: Information Age Publishing, pp. 25–74. [Google Scholar]

- Tafolli, Festim, and Sonja Grabner-Kräuter. 2020. Employee perceptions of corporate social responsibility and organizational corruption: Empirical evidence from Kosovo. Corporate Governance 20: 1349–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenbrunsel, Ann E., and Kristin Smith-Crowe. 2008. 13 ethical decision making: Where we’ve been and where we’re going. Academy of Management Annals 2: 545–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño, Linda Klebe. 1986. Ethical decision making in organizations: A person-situation interactionist model. Academy of Management Review 11: 601–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño, Linda Klebe, and Gary R. Weaver. 2001. Organizational justice and ethics program “follow-through”: Influences on employees’ harmful and helpful behavior. Business Ethics Quarterly 11: 651–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño, Linda Klebe, and Katherine A. Nelson. 2021. Managing Business Ethics: Straight Talk about How to Do it Right. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Treviño, Linda Klebe, and Michael Brown. 2004. Managing to be ethical: Debunking five business ethics myths. Academy of Management Perspectives 18: 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño, Linda Klebe, and Stuart A. Youngblood. 1990. Bad apples in bad barrels: A causal analysis of ethical decision-making behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology 75: 378–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño, Linda Klebe, Gary R. Weaver, and Scott J. Reynolds. 2006. Behavioral ethics in organizations: A review. Journal of Management 32: 951–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño, Linda Klebe, Kenneth D. Butterfield, and Donald L. McCabe. 1998. The ethical context in organizations: Influences on employee attitudes and behaviors. Business Ethics Quarterly 8: 447–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño, Linda Klebe, Laura Pincus Hartman, and Michael Brown. 2000. Moral person and moral manager: How executives develop a reputation for ethical leadership. California Management Review 42: 128–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño, Linda Klebe, Michael Brown, and Laura Pincus Hartman. 2003. A qualitative investigation of perceived executive ethical leadership: Perceptions from inside and outside the executive suite. Human Relations 56: 5–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño, Linda Klebe, Niki A. Den Nieuwenboer, and Jennifer J. Kish-Gephart. 2014. (Un) ethical behavior in organizations. Annual Review of Psychology 65: 635–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, Feng-Chiao, Yu-Tsung Huang, Luan-Yin Chang, and Jin-Town Wang. 2008. Pyogenic liver abscess as endemic disease, Taiwan. Emerging Infectious Diseases 14: 1592–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalikis, John, and David J. Fritzsche. 2013. Business Ethics: A Literature Review with a Focus on Marketing Ethics. In Citation Classics from the Journal of Business Ethics. Edited by Alex C. Michalos and Deborah C. Poff. Advances in Business Ethics Research. Dordrecht: Springer, vol. 2, pp. 337–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ülkü, Tugay, and Musa Said Döven. 2021. The Moderator role of ethical climate upon the effect between health personnel’s Machiavellian tendencies and whistleblowing intention: The case of Eskişehir. Is AhlakıDergisi 14: 125–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, Jean, and Attila Szabo. 2003. Academic offences and e-learning: Individual propensities in cheating. British Journal of Educational Technology 34: 467–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uusitalo, Outi, and Reetta Oksanen. 2004. Ethical consumerism: A view from Finland. International Journal of Consumer Studies 28: 214–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, Sean, and Tim Barnett. 2007. Perceived organizational ethics and the ethical decisions of sales and marketing personnel. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management 27: 373–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Val-Laillet, David, Esther Aarts, Bernhard M. Weber, Marco M. D. Ferrari, Valentina Quaresima, Luke Edward Stoeckel, Miguel Alonso-Alonso, Michel Albert Audette, Charles Henri Malbert, and Eric M. Stice. 2015. Neuroimaging and neuromodulation approaches to study eating behavior and prevent and treat eating disorders and obesity. NeuroImage: Clinical 8: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallaster, Christine, Sascha Kraus, José M. Merigó Lindahl, and Annika Nielsen. 2019. Ethics and entrepreneurship: A bibliometric study and literature review. Journal of Business Research 99: 226–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, Nees, and Ludo Waltman. 2010. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 84: 523–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Quaquebeke, Niels, Jan U. Becker, Niko Goretzki, and Christian Barrot. 2019. Perceived ethical leadership affects customer purchasing intentions beyond ethical marketing in advertising due to moral identity self-congruence concerns. Journal of Business Ethics 156: 357–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardaman, James M., Maria B. Gondo, and David G. Allen. 2014. Ethical climate and pro-social rule breaking in the workplace. Human Resource Management Review 24: 108–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, Bart, and John B. Cullen. 1988. The organizational bases of ethical work climates. Administrative Science Quarterly 33: 101–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitell, Scott J., Robert Allen King, Katharine Howie, Jean-François Toti, Lumina Albert, Encarnación Ramos Hidalgo, and Omneya Yacout. 2016. Spirituality, moral identity, and consumer ethics: A multi-cultural study. Journal of Business Ethics 139: 147–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vošner, Helena Blažun, Samo Bobek, Simona Sternad Zabukovšek, and Peter Kokol. 2017. Openness and information technology: A bibliometric analysis of literature production. Kybernetes 46: 750–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, Margaret Urban. 2007. Moral Understandings: A Feminist Study in Ethics. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Yau-De, and Hui-Hsien Hsieh. 2012. Toward a better understanding of the link between ethical climate and job satisfaction: A multilevel analysis. Journal of Business Ethics 105: 535–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wartick, Steven L., and Philip L. Cochran. 1985. The evolution of the corporate social performance model. Academy of ManagementReview 10: 758–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegmann, Alex, and Michael R. Waldmann. 2014. Transfer effects between moral dilemmas: A causal model theory. Cognition 131: 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, Donna J. 1991. Corporate social performance revisited. Academy of Management Review 16: 691–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, Rambalak. 2016. Altruistic or egoistic: Which value promotes organic food consumption among young consumers? A study in the context of a developing nation. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 33: 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yardley, Jennifer, Melanie Domenech Rodríguez, Scott C. Bates, and Johnathan Nelson. 2009. True confessions?: Alumni’s retrospective reports on undergraduate cheating behaviors. Ethics & Behavior 19: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Nan, Tung-Boon Kueh, Lisong Hou, Yongxin Liu, and Hang Yu. 2020. A bibliometric analysis of corporate social responsibility in sustainable development. Journal of Cleaner Production 272: 122679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukl, Gary. 2006. Leadership in Organizations, 6th ed. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Zandi, GholamReza, Imran Shahzad, Muhammad Farrukh, and Sebastian Kot. 2020. Supporting Role of Society and Firms to COVID-19 Management among Medical Practitioners. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 7961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zemigala, Marcin. 2019. Tendencies in research on sustainable development in management sciences. Journal of Cleaner Production 218: 796–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Guangxi, Jianan Zhong, and Muammer Ozer. 2020. Status threat and ethical leadership: A power-dependence perspective. Journal of Business Ethics 161: 665–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Qian, Bee Lan Oo, and Benson Teck Heng Lim. 2019. Drivers, motivations, and barriers to the implementation of corporate social responsibility practices by construction enterprises: A review. Journal of Cleaner Production 210: 563–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohar, Dov. 2010. Thirty years of safety climate research: Reflections and future directions. Accident Analysis & Prevention 42: 1517–22. [Google Scholar]

| Objectives | Method |

|---|---|

| Country | Bibliographic coupling |

| Keyword | Co-occurrence |

| Publication | Bibliographic coupling and Co-citation |

| Journal | Bibliographic coupling and Co-citation |

| Author | Bibliographic coupling and Co-citation |

| Cluster (Number of Keywords) | The Theme of Research about Ethical Behavior in the Context | Context | Keywords |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (146) | Concerns about health problems | Medical | Care; health; depression; cancer; medicine; stress; quality-of-life; risk; burnout; children; COVID-19; vulnerability; care; human-rights; psychology, life, family; HIV; suicide; bioethics; health-care; nurse |

| 2 (75) | Management work of leaders | Leadership | Performance; ethical leadership; model; ethical decision-making; job-satisfaction; ethical climate; employee voice; work; transformational leadership; abusive supervision |

| 3 (54) | Consumer behavior toward products of a socially responsible firm | Consumption | Corporate social-responsibility; corporate social responsibility; planned behavior; consumers; intentions; consumption; green; consumer behavior; product; welfare; welfare animal; responsibility; sustainability |

| 4 (51) | Understand the process of making an ethical decision | Ethical decisionmaking | Ethics; judgment; decision making; power; empathy; morality; emotion; dilemmas; psychologists, dynamics, intuition, negotiation, willingness |

| 5 (37) | Student’s behavior in education | Academic | Education; students; organization; managers; depletion; misconduct; integrity; cheating; academic dishonesty; unethical behavior |

| 6 (30) | Activities in corporate (business, management) | Corporate | Behavior; business ethics; codes; management; entrepreneurship; work climate; financial performance; human resource management; stakeholder theory |

| 7 (23) | The concept of factors mentioned when marketing | Marketing | Marketing ethics; consumer ethics; religiosity; collectivism; decision-making; idealism; social responsibility; culture; strategy |

| 8 (6) | Spirituality and virtue affect ethical behavior in Indian firms | Spiritual | Firms; India; philosophy; spirituality; virtue; workplace spirituality |

| Journal | Country | Publications | SJR 2021 | Quartile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Journal of Business Ethics (1982) | Netherlands | 143 | 2.44 | Q1 |

| Journal of Applied Psychology (1917) | UK | 24 | 6.45 | Q1 |

| Ethics and Behavior (1991) | USA | 17 | 0.44 | Q2 |

| Sustainability (2009) | Switzerland | 17 | 0.66 | Q1 |

| Science and Engineering Ethics (1995) | Netherlands | 15 | 1.07 | Q1 |

| Frontiers in Psychology (2010) | Switzerland | 10 | 0.87 | Q1 |

| Academic Medicine (1964) | USA | 10 | 1.66 | Q1 |

| Business Ethics Quarterly (1996) | UK | 9 | 1.54 | Q1 |

| Journal of Business Research (1973) | USA | 9 | 2.32 | Q1 |

| Personnel Review (1971) | UK | 5 | 0.89 | Q2 |

| Business Ethics (1992) | UK | 5 | 0.93 | Q1 |

| Cluster | Representative Research |

|---|---|

| Cluster 1 (37 publications) Ethical Decision Making | Ajzen (1991); Ferrell and Gresham (1985); Fornell and Larcker (1981); Fornell and Larcker (1981); Hunt and Vitell (1986); Jones (1991); Rest (1986); Treviño (1986); Fishbein and Ajzen (1977) |

| Cluster 2 (34 publications) Ethical Leadership | Brown et al. (2005); Brown and Treviño (2006); Mayer et al. (2009); Treviño et al. (2003); Treviño et al. (2000); Piccolo et al. (2010); Brown and Mitchell (2010); Bedi et al. (2016); De Hoogh and Den Hartog (2008) |

| Cluster 3 (23 publications) Ethical Judgment, Moral Development, and Ethical Behavior in an Organization | Aquino and Reed (2002); Bandura (1999); Greene et al. (2001); Haidt (2001); Mazar et al. (2008); Treviño and Youngblood (1990); Treviño et al. (2006); Tenbrunsel and Smith-Crowe (2008) |

| Cluster 4 (6 publications) Ethical Climate | Victor and Cullen (1988); Treviño et al. (1998); Schwepker (2001) |

| Journal | Country | Citation | SJR 2021 | Quartile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Journal of Business Ethics (1982) | Netherlands | 4775 | 2.44 | Q1 |

| Journal of Applied Psychology (1917) | USA | 1326 | 6.45 | Q1 |

| Academy of Management Review (1978) | USA | 1006 | 7.62 | Q1 |

| Academy of Management Journal (1975) | USA | 908 | 10.87 | Q1 |

| Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (1965) | USA | 895 | 3.7 | Q1 |

| Leadership Quarterly (1990) | USA | 639 | 4.91 | Q1 |

| Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes (1985) | USA | 577 | 2.83 | Q1 |

| Journal of Business Research (1973) | USA | 538 | 2.32 | Q1 |

| Journal of Management (1975) | USA | 525 | 2.12 | Q1 |

| Journal of Marketing (1969) | USA | 522 | 7.46 | Q1 |

| Science (1880) | USA | 375 | 14.59 | Q1 |

| Business Ethics (1992) | UK | 358 | 0.93 | Q1 |

| A. Bibliographic Coupling Analysis | B. Co-Citation Analysis | C. Key Context |

|---|---|---|

| Cluster 2 (131 Publications) Ethical Behavior in Consumption | Cluster 1 (37 publications) Ethical Decision Making | Consumption |

| Cluster 4 (119 Publications) Ethical Behavior in Leadership | Cluster 2 (34 publications) Ethical Leadership | Leadership |

| Cluster 3 (129 Publications) Moral Development, Ethical Perception, Moral Judgment, and Ethical Decision Making | Cluster 3 (23 publications) Ethical Judgment, Moral Development, and Ethical Behavior in Organizations | Business |

| Cluster 5 (78 Publications) Ethical Behavior in Business: Corporate Social Responsibility | ||

| Cluster 6 (64 Publications) (Un)Ethical Behavior in Organizational Contexts | Cluster 4 (6 publications) Ethical Climate | Organization |

| Cluster 8 (16 Publications) Ethical Climate in Organizational Contexts | ||

| Cluster 1 (435 publications) Medical Contexts | Medical | |

| Cluster 7 (27 Publications) (Un)Ethical Behavior in Educational Contexts | Education |

| Main Concept | Explanation | Authors |

|---|---|---|

| Altruistic consumption | Customers choose forms of consumption that are not environmentally friendly | Smith and Paladino (2010); Yadav (2016) |

| Exchanging behavior | Using the ethical values of the exchange product | Husser et al. (2019); Van Quaquebeke et al. (2019) |

| Fair trade (FT) practice | These include (1) willingness to pay more, (2) guidance by universalism, benevolence, self-direction and stimulation, (3) self-identity, (4) emphasis on brand fair trade in products, and (5) cultural influences | Gram-Hanssen (2021); Gregory-Smith et al. (2017) |

| Frugal consumption | Customers are less interested in shopping, more physical repair and product reuse, longer product life | Gregory-Smith et al. (2017); Gatersleben et al. (2019) |

| Green consumption | Customers drive communities and practices at the national level, which forces manufacturers to adhere to environmentally friendly products | Stern et al. (1995); Gregory-Smith et al. (2017) |

| Socially conscious consumption behavior | Consider equity between environmental issues (e.g., use of used products), health (e.g., building low-waste communities) and social issues (e.g., donate unused products) | Pepper et al. (2009); Romani et al. (2016) |

| Socially responsible consumption behavior | These include buying behavior (e.g., buying used products), non-buying behavior (e.g., discouraging purchasing products using raw materials), and post-purchase behavior (e.g., sell fully functional used products at lower market prices) | Johnson and Chattaraman (2019); Kang and Namkung (2018) |

| Spiritual and moral consumption | Consumer spiritual practices promote ethical consumption | Orellano et al. (2020); Vitell et al. (2016) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vu Lan Oanh, L.; Tettamanzi, P.; Tien Minh, D.; Comoli, M.; Mouloudj, K.; Murgolo, M.; Dang Thu Hien, M. How Ethical Behavior Is Considered in Different Contexts: A Bibliometric Analysis of Global Research Trends. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14090200

Vu Lan Oanh L, Tettamanzi P, Tien Minh D, Comoli M, Mouloudj K, Murgolo M, Dang Thu Hien M. How Ethical Behavior Is Considered in Different Contexts: A Bibliometric Analysis of Global Research Trends. Administrative Sciences. 2024; 14(9):200. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14090200

Chicago/Turabian StyleVu Lan Oanh, Le, Patrizia Tettamanzi, Dinh Tien Minh, Maurizio Comoli, Kamel Mouloudj, Michael Murgolo, and Mai Dang Thu Hien. 2024. "How Ethical Behavior Is Considered in Different Contexts: A Bibliometric Analysis of Global Research Trends" Administrative Sciences 14, no. 9: 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14090200

APA StyleVu Lan Oanh, L., Tettamanzi, P., Tien Minh, D., Comoli, M., Mouloudj, K., Murgolo, M., & Dang Thu Hien, M. (2024). How Ethical Behavior Is Considered in Different Contexts: A Bibliometric Analysis of Global Research Trends. Administrative Sciences, 14(9), 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14090200