Abstract

This study explores the relationship between digital access, protection, and adoption in supporting technological entrepreneurship within national digital ecosystems. The study utilised PROCESS regression analysis on the Global Entrepreneurship Development Institute (GEDI)’s Digital Development Economy (DPE) Index 2020 dataset to examine selected digital factors’ direct and indirect effects on entrepreneurial activity across 116 countries. While the relationship between digital access, adoption, protection, and technological entrepreneurship has been established in previous research, this study provides global evidence to reinforce this connection. However, digital protection did not significantly moderate the effect of digital access. Notably, digital adoption emerged as a significant mediator, influencing the impacts of both access and protection on entrepreneurial outcomes. This study emphasises the importance of understanding the complex relationships between digital factors in cultivating a thriving entrepreneurial ecosystem, offering valuable insights for policymakers and practitioners seeking to stimulate technological innovation and economic growth.

1. Introduction

The rise of digital technologies has drastically transformed the entrepreneurial landscape, especially in the technology sector (Paul et al. 2023). The proliferation of digital platforms, tools, and services such as social media, e-commerce platforms, cloud computing services, content management systems, and communication and collaboration tools, among others, has provided new opportunities for technology entrepreneurs around the world to innovate, gain market access, and grow (Elia et al. 2020; Fernandes et al. 2022; Satalkina and Steiner 2020). However, the success of technological entrepreneurship is dependent not only on the availability of digital technologies but also on a supportive digital ecosystem that promotes innovation and growth (Fernandes et al. 2022; Zahra et al. 2023). The term digital ecosystem describes a complex, interconnected network encompassing actors, technologies, institutions, and processes that collectively create and deliver value through digital platforms and services (Elia et al. 2020). It includes hardware, software, data, networks, organisations, regulations, and user communities (Sussan and Acs 2017).

The extant literature (for instance, Bican and Brem 2020; Elia et al. 2020; Proksch et al. 2024; Sahut et al. 2021; Zhao and Weng 2024) extensively explores the link between digital factors and entrepreneurship. Some studies, such as Koomson et al. (2023) and Steininger (2019), focus on the value of digital access, emphasising how internet connectivity and tools enable entrepreneurs to launch and grow their ventures. Others delve into digital protection, highlighting the need for robust cybersecurity and intellectual property rights frameworks to foster digital entrepreneurship (Jiao et al. 2022; Zhao and Weng 2024). While a consensus exists on the significance of digital factors, there is no clarity on which of these elements exerts the greatest influence on entrepreneurship. Additionally, the optimal level of government intervention in promoting and regulating digital entrepreneurship remains a subject of debate, with some advocating for minimal intervention and others calling for more active support (Jiao et al. 2022; Zhao and Weng 2024). Moreover, many previous studies tended to overlook a comprehensive examination of the relationship between digital access, protection, and adoption, and their combined effects on technological entrepreneurship. The lack of understanding regarding the complex interplay of these factors and their relative contributions creates a significant research gap. This is particularly true in developing countries where the digital landscape is rapidly evolving and entrepreneurs face unique challenges and opportunities (Soluk et al. 2021).

Investigating this gap is crucial for enhancing our understanding of the digital ecosystem and its impact on technological entrepreneurship. By unravelling the connections between access, protection, and adoption, this research will contribute to a more nuanced and comprehensive theoretical framework for understanding the drivers of digital entrepreneurship. Moreover, the findings will inform policymakers, entrepreneurs, and investors in developing effective strategies to foster a thriving digital entrepreneurial ecosystem.

Against the above-mentioned background, this study addresses the following research questions:

- (a)

- To what extent do digital access, protection, and adoption individually and collectively influence the level of technological entrepreneurship in a country?

- (b)

- Does digital protection moderate the relationship between digital access and technological entrepreneurship, and if so, how?

- (c)

- What is the mediating role of digital adoption in the relationships between digital access, protection, and technological entrepreneurship?

The remainder of the paper is organised as follows: First, a literature review is provided. The research design and methodology are then presented, followed by the study’s results. The results are then discussed in detail, and implications for practice and theory are outlined. The paper ends with the conclusions and suggestions for future research.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. The Digital Revolution and Its Impact on Technological Entrepreneurship

The profound impact of the digital revolution on the entrepreneurial landscape in many parts of the world is widely recognised (Bican and Brem 2020; Elia et al. 2020; Steininger et al. 2022). Technological entrepreneurship, also known as digital entrepreneurship, which is characterised by the creation and growth of ventures that leverage digital technologies for innovative products or services, has emerged as a key driver of economic growth and societal advancement (Petti and Zhang 2011). Some empirical studies infer positive interlinkages between the robustness of an area’s digital ecosystem and the degree of entrepreneurial activity therein (Elia et al. 2020; Zahra et al. 2023). It is observed that digital technologies lower barriers to entry, democratise access to information and resources, and enable the creation of new business models (Bican and Brem 2020; Kraus et al. 2019; Steininger 2019). These, in turn, play pivotal roles in fostering innovation, driving economic growth, and creating employment opportunities (Zhao and Weng 2024). The present literature review delves into the multifaceted digital ecosystem and its impact on technological entrepreneurship, examining how the key components of the digital ecosystem influence the emergence, growth, and success of technology-driven ventures.

2.2. Digital Access and Technological Entrepreneurship

Digital access, defined as the ability of individuals and businesses to utilise digital technologies such as the internet, mobile devices, and computers (Gomes and Lopes 2022), is widely recognised as a critical factor in technological entrepreneurship. Existing research indicates a strong correlation between digital access and entrepreneurial activity, particularly in the realm of digital innovation (Gigauri et al. 2023; Koomson et al. 2023; Lythreatis et al. 2022; Nguyen et al. 2024; Reddick et al. 2020; Soluk et al. 2021).

Specifically, increased internet penetration and broadband availability have been linked to a rise in entrepreneurial endeavours (Chen et al. 2018; Pipitwanichakarn and Wongtada 2020). Digital access provides entrepreneurs with a wealth of information, knowledge, and resources, fostering an environment conducive to innovation. Additionally, online platforms facilitate collaboration, knowledge sharing, and access to open-source tools, thereby accelerating the innovation process (Linzalone et al. 2020).

Furthermore, digital access enables entrepreneurs to reach a global audience with minimal initial investment (Watson et al. 2018). E-commerce platforms, social media, and digital marketing tools have democratised access to markets, allowing entrepreneurs to connect with customers, suppliers, and partners across geographical boundaries (Pereira et al. 2023). This expanded market reach can significantly boost sales, revenue, and overall business growth.

Moreover, digital access unlocks a plethora of growth opportunities for technological entrepreneurs. Cloud computing services offer scalable and cost-effective infrastructure (Li and Yao 2021), while digital payment systems facilitate seamless transactions, enabling entrepreneurs to tap into new markets and revenue streams (Ogunmuyiwa and Amida 2022).

However, barriers to digital access, particularly in developing countries and underserved communities, persist. These barriers include the high cost of internet access, lack of digital skills, and infrastructural gaps in rural and remote areas (Cumming et al. 2022; Liu et al. 2022; Morris et al. 2022; Zhao and Weng 2024). Such challenges create a digital divide, excluding a significant portion of potential entrepreneurs from the digital economy (Lythreatis et al. 2022). Despite these obstacles, the positive impact of digital access on technological entrepreneurship is evident. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1.

Digital access has a positive influence on technological entrepreneurship.

2.3. Digital Protection and Technological Entrepreneurship

Digital protection, which includes cybersecurity measures and intellectual property rights (IPRs) (GEDI 2020), is critical for creating a safe and trustworthy digital ecosystem. By safeguarding digital assets and intellectual property against unauthorised access, theft, and misuse, digital protection provides a foundation upon which entrepreneurs can confidently innovate (Chandna and Tiwari 2023; Pathak et al. 2013).

Empirical evidence suggests that digital protection and technological entrepreneurship are positively related. According to a European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) study (2021), stronger intellectual property rights protection in EU countries correlates with improved firm performance. Yang et al. (2014) found that robust IPR regimes promote innovation, especially in high-income economies. Hasani et al. (2023) revealed a positive relationship between cybersecurity technology adoption and organisational performance in UK SMEs.

However, while strong digital protection is generally beneficial, overly stringent measures can be problematic. Excessive protection may stifle innovation and competition by restricting entrepreneurs’ ability to expand on existing ideas and technologies (Gyedu et al. 2024). Pathak et al. (2013) caution that overly aggressive IPR enforcement can stifle creativity and technological entrepreneurship. Policymakers, therefore, must strike a delicate balance between protection and innovation to foster a conducive environment for technological entrepreneurship, thereby driving economic growth and technological advancement.

Given these considerations, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2.

Digital protection positively influences digital entrepreneurship.

2.4. Digital Adoption and Technological Entrepreneurship

Digital adoption describes the complex process through which individuals, businesses, and societies embrace and integrate digital technologies into their operations and strategies (Orser et al. 2019). This concept encompasses various dimensions, including technology usage, digital skill development, and organisational transformation (Lee et al. 2021). Previous research has consistently demonstrated a strong positive correlation between digital adoption and technological entrepreneurship, with some studies finding that entrepreneurs who effectively adopt digital technologies are more likely to experience enhanced entrepreneurial capabilities, increased productivity, and improved competitiveness (Berman et al. 2023; Holzmann and Gregori 2023; Paul et al. 2023; Steininger et al. 2022; Zhang et al. 2023). According to Zahra et al. (2023) businesses that adopt digital technologies are more likely to introduce innovative solutions and stay competitive in the market. Furthermore, digital tools such as e-commerce platforms, social media, and digital marketing strategies enable entrepreneurs to reach broader and more diverse markets, allowing businesses to connect with customers globally (Pereira et al. 2023). Likewise, digital technologies, through automation, cloud computing, and data analytics, also enable businesses to optimise their processes, reducing costs and improving productivity (Choi et al. 2016; Muhammad et al. 2018).

Despite these benefits, several barriers can hinder digital adoption. Mkansi (2022) found that access to funding and affordable technology solutions is crucial for promoting digital adoption among SMEs, who often struggle with limited financial resources. Similarly, Kergroach (2021) reports that a lack of digital skills remains a major obstacle, which indicates the importance of upskilling and reskilling the workforce to keep pace with technological advancements. Based on the findings from previous studies, it is hypothesised that:

H3.

Digital adoption has a positive influence on digital entrepreneurship.

2.5. Interplay of Digital Access, Protection, and Adoption

Despite ongoing research, significant gaps exist in understanding the complex interplay of digital access, protection, and adoption in fostering technological entrepreneurship. While each element is significant, there is uncertainty about their relative importance and interaction effects. Some studies prioritise access, claiming that it is essential for other factors (e.g., Pipitwanichakarn and Wongtada 2020; Li and Yao 2021). Others emphasise the importance of protection as a prerequisite for taking entrepreneurial risks (Martin et al. 2019; Deloitte 2013). More research is required to disentangle these relationships. Furthermore, the mechanisms by which these factors affect entrepreneurship are unclear. For example, while digital access broadens markets, its precise impacts on innovation and entrepreneurial behaviour remains unclear. More research is needed to identify the causal pathways. By addressing these gaps, a more nuanced understanding of the digital ecosystem and its impact on technological entrepreneurship is obtained. The subsections that follow propose specific mechanisms for how digital access, protection, and adoption interact with technological entrepreneurship.

2.5.1. Moderating Role of Digital Protection

Previous research has examined the impact of digital protection on the interplay between digital access, adoption, and entrepreneurship, revealing a complex landscape. Robust digital protection mechanisms appear to strengthen the link between digital access and adoption, while also creating a more favourable environment for technological entrepreneurship (Chen and Wu 2022; Chen et al. 2023). For instance, tailored cybersecurity solutions have been identified as critical for businesses to thrive in the digital age by protecting them from the negative effects of cyber threats (Anonymous 2022). Furthermore, intellectual property rights play an important role in reinforcing the relationship between information availability and technology entrepreneurship, emphasising the significance of legal frameworks in fostering innovation (Yeganegi et al. 2021).

However, the impact of digital protection varies, depending on the actor and the context. Michota (2013) emphasises that security concerns are a significant barrier for female entrepreneurs, highlighting the need for tailored digital protection strategies that take into account the unique challenges that different groups face. While website security and content have been shown to improve user experience and trust, thereby increasing adoption (Natarajan et al. 2012), the interaction of digital and institutional affordances can be complex. For example, Liu et al. (2023) discovered that intellectual property rights protection systems can harm the relationship between digital innovation adoption, innovation speed, and operating efficiency. To improve our understanding of digital protection’s multifaceted role, more research is needed to investigate its moderating effect in diverse contexts using a variety of methodologies and data sources.

Based on the existing literature and the potential mechanisms identified, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H4.

Digital protection moderates the positive relationship between digital access and digital adoption.

H5.

Digital protection moderates the positive relationship between digital adoption and digital entrepreneurship.

2.5.2. The Mediating Effect of Digital Adoption

The relationship between digital protection and entrepreneurial outcomes is multifaceted, extending beyond a simple direct correlation (Martin et al. 2019). Whilst a secure digital environment, fostered by robust cybersecurity measures and data privacy regulations, is conducive to entrepreneurship (Chandna and Tiwari 2023), it does not automatically guarantee success. Research often reveals a positive association between strong digital protection frameworks and increased entrepreneurial activity, particularly in technological sectors (Chandna and Tiwari 2023; Pathak et al. 2013; Shepherd and Majchrzak 2022), but this correlation does not necessarily imply causation. Other factors, including the ease of doing business, access to talent, market size, economic stability, education levels, access to capital, and cultural attitudes towards risk-taking, play significant roles in shaping entrepreneurial outcomes (Gawer 2022; Manimala et al. 2019; Sheriff and Muffatto 2015; Zahra et al. 2023; Zhang et al. 2023). For instance, some European countries with stringent data protection regulations have not experienced a proportional surge in digital entrepreneurship compared to countries with more relaxed regulations but dynamic entrepreneurial cultures (Deloitte 2013). This observation underscores that while digital protection is essential, it is not the sole determinant. A balanced approach to digital protection that fosters trust and security without stifling entrepreneurial creativity and agility is therefore crucial. Some studies underscore the complementary roles of some elements of the entrepreneurial ecosystems in translating the benefits of digital protection into tangible entrepreneurial success (De Bernardi et al. 2020; Cantner et al. 2021).

This study proposes that digital adoption through, inter alia, the use of digital tools and online presence, serves as a crucial mediating factor in the relationship between digital access and digital entrepreneurship. It posits that digital protection enhances digital access, which, in turn, fosters digital adoption. This adoption then enables entrepreneurs to confidently engage in online activities, reducing the risk of cyberattacks and data breaches while simultaneously expanding market reach. Data from Gomes and Lopes (2023) and Zhang et al. (2023) indicate a positive correlation between countries with high digital adoption rates and vibrant entrepreneurial ecosystems, particularly in the technology sector. Based on this, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H6.

Digital adoption mediates the relationship between digital access and digital entrepreneurship.

H7.

The mediating effect of digital adoption on the relationship between digital access and digital entrepreneurship is stronger in environments with robust digital protection measures.

3. Research Design and Methodology

This study uses a quantitative, cross-sectional research design to examine the relationships between digital access, protection, and adoption, as well as their effects on technological entrepreneurship. Secondary data were sourced from the GEDI Institute’s Digital Platform Economy (DPE) Index 2020 dataset, which covers 116 countries and tracks the growth of the digital platform economy. This dataset has a large sample size, allowing for cross-national comparisons and an investigation of complex interactions between the variables under consideration.

3.1. Measurement and Operationalisation of Variables

The study focuses on four main variables. These are described below.

- Digital access: This variable, measured by the DPE Index’s digital access sub-index, captures the extent to which individuals and businesses can utilise digital technologies (e.g., internet penetration, mobile phone usage, and broadband availability).

- Digital protection: This variable, operationalised through the DPE Index’s digital protection sub-index, assesses the strength of cybersecurity measures and intellectual property rights frameworks (e.g., cybersecurity readiness and intellectual property protection).

- Digital adoption: This variable, measured by the DPE Index’s digital adoption sub-index, reflects the degree to which digital technologies are integrated into business operations and strategies (e.g., use of digital tools and online presence).

- Technological entrepreneurship: This variable, calculated using the DPE Index’s technology entrepreneurship sub-index, measures the level of entrepreneurial activity in the technology sector (e.g., number of new technology ventures and investment in technology startups).

To account for potential confounding factors, the study includes one control variable, per capita gross domestic product (GDP), which is known to impact both digital development and entrepreneurial activity.

3.2. Statistical Analysis

To investigate the direct and indirect effects of digital access, protection, and adoption on technological entrepreneurship, PROCESS regression analysis is used (Hayes 2018). The software Smart PLS 4 by Ringle et al. (2024) was used for this purpose. PROCESS is essentially an extension of multiple regression analysis but is particularly well-suited for analysing moderating and mediating effects because it allows a thorough examination of the interactions between multiple predictors, mediators, and moderators. The analysis entails identifying the key variable, specifying the model, and lastly, model estimation. To ensure the robustness of the results, bootstrapping is used to estimate the indirect effects. Before the PROCESS analysis, descriptive statistics and Spearman’s correlation tests are used to improve understanding of the variables’ distributions and relationships.

3.3. Ethical Considerations

This study is based on publicly available secondary data from the GEDI Institute’s DPE Index 2020 dataset. As a result, no primary data were collected, and ethical approval was not required. Nonetheless, rigorous research ethics were followed by identifying the data source and ensuring accurate reporting and interpretation of the findings.

4. Results

Table 1 illustrates descriptive statistics for five key variables associated with the digital ecosystem and technological entrepreneurship in 116 countries: digital access, digital protection, digital adoption, per capita GDP, and technological entrepreneurship.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

The mean scores for digital access, protection, and adoption are virtually identical (36.23, 36.23, and 36.22, respectively). However, each shows significant variation across countries, with standard deviations ranging from 22.37 (adoption) to 28.81 (access). The wide range of per capita GDP (USD 702 to USD 116,936) reflects substantial economic disparities between countries, which are likely to influence digital capabilities and entrepreneurial activity. Technological entrepreneurship scores vary moderately (9.3 to 92.3).

These preliminary findings suggest potential interrelationships among digital access, protection, and adoption. The broad range of values for all variables highlights the diversity of the global digital landscape. The large standard deviation in per capita GDP highlights the significant economic disparities between countries, potentially affecting their digital capabilities and entrepreneurial endeavours.

This descriptive analysis lays the groundwork for understanding the distribution and variability of key variables. Further statistical analyses will examine the relationships between these factors to further comprehend the complex interplay within the digital ecosystem and the effects on technological entrepreneurship.

4.1. Normality Assessment

The Shapiro–Wilk test for multivariate normality was conducted to assess whether the data met the assumption of normality. The test yielded a statistically significant result (Shapiro–Wilk = 0.634, p < 0.001), indicating that the data significantly deviated from a multivariate normal distribution. The results are illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Assumption checks: Shapiro–Wilk test for multivariate normality.

4.2. Spearman’s Rank Correlation Analysis

Spearman’s rank correlation analysis was performed to assess the relationships between digital technology entrepreneurship, digital access, digital protection, digital adoption, and per capita GDP. The outcome is presented in Table 3. The results revealed significant positive correlations between all variables.

Table 3.

Spearman’s correlation test results.

Specifically, technological entrepreneurship demonstrated very strong positive correlations with digital access (rho = 0.897, p < 0.001), digital adoption (rho = 0.942, p < 0.001) and digital protection (rho = 0.909, p < 0.001). This suggests that countries with higher levels of digital access, digital adoption, and protection tend to exhibit greater levels of technological entrepreneurship.

Similarly, a very strong positive correlation was found between digital access and digital protection (rho = 0.890, p < 0.001), indicating that countries with greater digital access also tend to have stronger digital protection measures in place.

Furthermore, all four variables—technological entrepreneurship, digital access, digital adoption, and digital protection—exhibited very strong positive correlations with per capita GDP (2017) (rho = 0.873, 0.881, 0.901 and 0.886, respectively, all p < 0.001). This suggests that higher levels of economic growth are associated with greater digital access, increased digital adoption, stronger digital protection, and increased technological entrepreneurship.

These findings underscore the interconnected nature of these factors within the digital ecosystem. While a correlation does not imply causation, the strong positive relationships suggest that digital access, digital protection, and economic growth may play mutually reinforcing roles in fostering digital entrepreneurship. A further analysis was then conducted to determine the explanatory relationships between these variables and to identify potential mediating or moderating factors that may influence these relationships.

4.3. PROCESS Regression Analysis

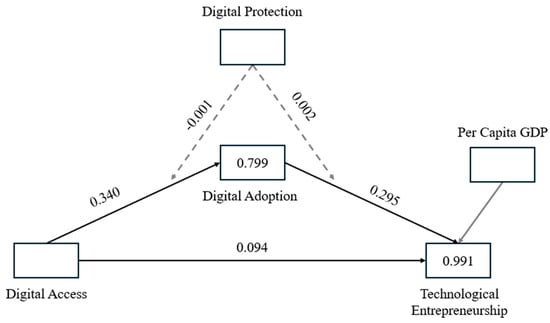

The computer software Smart PLS version 4 was used to run the PROCESS regression test. Figure 1 illustrates the relationships between digital access, digital adoption, digital protection, and technological entrepreneurship, with per capita GDP as a control variable.

Figure 1.

Path diagram of the relationships between digital access, digital adoption, digital protection, and technological entrepreneurship. Source: Authors’ own work.

The details of the direct and indirect effects of the predictors on the independent variable are captured in Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6. The results of the analysis, summarised in Table 4, demonstrate significant direct effects of both digital access and protection on technological entrepreneurship across the 116 countries analysed. Specifically, digital access positively influences technological entrepreneurship (r = 0.094; p = 0.027). This finding suggests that improved digital access equips entrepreneurs with essential resources, facilitating the launch and growth of technology-driven ventures. Thus, the data provide support for hypothesis H1, which posits a positive relationship between digital access and technological entrepreneurship.

Table 4.

Direct path coefficients.

Table 5.

Control variables.

Table 6.

Specific indirect effects.

Furthermore, the data also substantiate hypothesis H2, confirming that digital protection positively influences digital entrepreneurship (r = 0.235; p = 0.005). The results also highlighted that digital protection did not significantly moderate the relationships between digital access and digital adoption (r = −0.01; p = 0.501), and digital adoption and technological entrepreneurship (r = 0.002; p = 0.132). Hypotheses 4 and 5 were therefore not supported by the data. It is worth noting that the control variable GDP per capita was not a significant predictor of technological entrepreneurship (see Table 5).

The control variable, per capita GDP, was not a significant predictor of technological entrepreneurship. The results are shown in Table 5.

The mediation analysis provides evidence in support of Hypothesis 6, confirming that digital adoption partially mediates the relationship between digital access and digital entrepreneurship (r = 0.1; p = 0.003). This suggests that the positive effect of digital access on digital entrepreneurship is partially channelled through increased digital adoption (see Table 6). However, Hypothesis 7, which posited that the mediating effect of digital adoption on the relationship between digital access and digital entrepreneurship is stronger in environments with robust digital protection measures, was not supported by the data (r 0.000; p = 0.525).

The R-square values (0.789 and 0.875) for digital adoption and (0.911 and 0.904) for technological entrepreneurship shown in Table 7 indicate that the hypothesised model accounted for approximately 79% of the variance in digital adoption and approximately 91% of the variance in technology entrepreneurship. This suggests that the included predictors (digital access, digital adoption, and digital protection) are strongly associated with both outcome variables. The findings of this study offer compelling evidence for the positive influence of digital access and protection on technological entrepreneurship.

Table 7.

R-square and adjusted R-square values.

Table 8 presents the f-square effect sizes for the relationships between digital access, protection, adoption, and technological entrepreneurship. In this context, f-square represents the effect size of a specific predictor variable (or a combination of variables in the case of interactions) on the dependent variable. It quantifies how much of the variance in the dependent variable (technological entrepreneurship in this case) is uniquely explained by the predictor variable. The interpretation of f-square values is as follows: 0.02 = small effect size; 0.15 = medium effect size; and 0.35 = large effect size.

Table 8.

F-square matrix.

The results indicated that digital adoption had the strongest unique contribution to explaining variance in technological entrepreneurship (f² = 0.506). Digital protection also had a large effect size on technological entrepreneurship (f² = 0.392). Digital access and the interaction of digital protection and adoption had a small effect size (f² = 0.064 and f² = 0.046, respectively).

5. Discussions of Findings

The findings of this study support and expand on the existing body of literature on the relationship between digital factors and technological entrepreneurship. These results support previous research (e.g., Gomes and Lopes 2022; Koomson et al. 2023; Lythreatis et al. 2022; Nguyen et al. 2024), confirming that digital access is a significant predictor of entrepreneurial activity. This finding emphasises the importance of internet connectivity and access to digital tools in empowering entrepreneurs to start and grow their businesses. While these findings underscore the critical roles of internet connectivity and digital tools, it is important to note that the impacts may vary across different regions and industries.

Furthermore, this study sheds new light on the nuanced relationship between digital protection and technological entrepreneurship. In line with the EUIPO (2021) study, this research found that stronger digital protection measures are associated with increased entrepreneurial activity. This finding infers that a secure digital environment, characterised by robust cybersecurity and well-defined intellectual property rights frameworks, is critical for fostering an environment of trust and confidence. This finding broadly supports the work of other studies in this area (e.g., Yang et al. 2014; Hasani et al. 2023) linking digital secure contexts to positive entrepreneurial outcomes. Such an environment encourages entrepreneurial risk-taking by mitigating the fear of intellectual property theft, cyberattacks, and data breaches. Moreover, strong digital protection measures can stimulate innovation by providing entrepreneurs with the confidence to invest in research and development.

Nevertheless, these results challenge some of the prevailing assumptions in the existing literature. Although all three variables were positively correlated with technological entrepreneurship, digital protection did not significantly moderate the relationship between digital access and technological entrepreneurship. The finding is somewhat surprising given the fact that other research (such as Chen and Wu 2022; Chen et al. 2023) demonstrates how digital protection strengthens the link between digital access and technological entrepreneurship. This finding implies that while digital protection is undoubtedly essential, its role in amplifying the impact of digital access on entrepreneurship may be more complex than previously thought.

This study underscores the critical mediating role of digital adoption in the relationship between digital access, protection, and technological entrepreneurship. The findings challenge the notion that simply providing access to digital technology and ensuring its security is insufficient to stimulate entrepreneurial activity. Instead, they emphasise the necessity of bridging the gap between access and utilisation. These findings support Kasim et al.’s (2024) discovery that technology adoption played a critical role in the relationship between entrepreneurship orientation and strategic entrepreneurship values among Malaysian Fintech organisations. This finding has important implications for policymakers and practitioners, including the need to cultivate a digital adoption-friendly environment while concurrently expanding access and enhancing protection.

Ultimately, this study complements the growing body of research on the digital ecosystem and its influence on technological entrepreneurship. It extends our understanding of the factors that drive technological innovation and economic growth by unravelling the complex relationships between digital access, protection, adoption, and entrepreneurial activity.

6. Conclusions

The findings of this study shed light on the dynamics of digital ecosystems and their impact on technological entrepreneurship. By unravelling the digital thread that connects access, protection, and adoption, the study provides a more nuanced understanding of how these factors interact to drive entrepreneurial success. These findings have several important implications for future policy and practice. Firstly, the study emphasises the importance of a supportive digital ecosystem in promoting technological entrepreneurship. The interconnected nature of digital access, protection, and adoption necessitates the formulation of comprehensive digital strategies.

Policymakers should prioritise enhancing digital infrastructure and lowering barriers to internet access, especially in underserved areas. Extending broadband connectivity and promoting low-cost internet services can significantly boost entrepreneurial activity. Furthermore, strong cybersecurity measures and intellectual property rights frameworks are required to create a safe environment that promotes innovation and investment. To avoid stifling entrepreneurial creativity, a delicate balance between protection and flexibility must be maintained.

Promoting digital adoption is equally important. Initiatives to improve digital skills and facilitate the adoption of digital technologies in businesses are critical. Providing training programmes and access to digital tools and cultivating a culture of continuous learning can help entrepreneurs leverage digital technologies for growth.

Finally, this study emphasises the unique challenges that countries with a low GDP face in terms of digital access, security, and adoption. As a result, a top policy priority in these areas should be to implement context-specific strategies that address infrastructure gaps, affordability concerns, and skill development needs. By doing so, policymakers can foster a more favourable environment for technological entrepreneurship in these regions.

7. Limitations and Areas for Future Research

Notwithstanding its contribution, the current study has a few limitations that should be acknowledged. The cross-sectional nature of the data precludes the establishment of definitive causal relationships. While the model controls for a variety of factors, there remains the possibility of omitted variable bias if other relevant variables are not included. Furthermore, the reliance on a single dataset may not fully capture the complex and multifaceted nature of the digital ecosystem.

Despite its limitations, this study provides valuable insights into the relationship between digital access and entrepreneurship. It is hoped that this research will stimulate further investigation into this important topic. Future research should employ longitudinal designs to examine the dynamic interplay between digital access and entrepreneurial outcomes over time. It is also crucial to incorporate a wider range of variables to enhance the robustness of the model and minimise potential biases. Additionally, future studies should consider utilising multiple datasets to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the digital landscape and its impact on entrepreneurial activities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.M.N. and R.S.; methodology, T.M.N.; software, T.M.N.; validation, T.M.N. and R.S.; formal analysis, T.M.N.; investigation, T.M.N.; resources, R.S.; data curation, T.M.N.; writing—original draft preparation, T.M.N.; writing—review and editing, R.S.; visualization, R.S.; project administration, T.M.N.; funding acquisition, R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by the University of South Africa.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data were extracted from the Digital Platform Economy Index 2020 and are available at https://thegedi.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/DPE-2020-Report-Final.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Anonymous. 2022. Digital defenses: The importance of cybersecurity in entrepreneurial ventures in the digital age. Strategic Direction 38: 24–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, Tal, David Stuckler, Daniel Schallmo, and Sascha Kraus. 2023. Drivers and success factors of digital entrepreneurship: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Journal of Small Business Management, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bican, Peter M., and Alexander Brem. 2020. Digital business model, digital transformation, digital entrepreneurship: Is there a sustainable “digital”? Sustainability 12: 5239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantner, Uwe, James A. Cunningham, Erik E. Lehmann, and Matthias Menter. 2021. Entrepreneurial ecosystems: A dynamic lifecycle model. Small Business Economics 57: 407–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandna, Vallari, and Praneet Tiwari. 2023. Cybersecurity and the new firm: Surviving online threats. Journal of Business Strategy 44: 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Qian, Yong Qi, and Guiyang Zhang. 2023. Digital economy, government intellectual property protection, and entrepreneurial activity in China. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Wen, and Ying Wu. 2022. Does intellectual property protection stimulate digital economy development? Journal of Applied Economics 25: 723–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Ying-Ju, Gizem Korpeoglu, Ersin Korpeoglu, Ozge Sahin, Christopher Tang, and Shihong Xiao. 2018. Innovative Online Platforms: Research Opportunities. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management 22: 430–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Tsan-Ming, Hing Kai Chan, and Xiaohang Yue. 2016. Recent developments in big data analytics for business operations and risk management. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics 47: 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, Douglas, Hisham Farag, Sofia Johan, and Danny McGowan. 2022. The digital credit divide: Marketplace lending and entrepreneurship. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 57: 2659–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bernardi, Paola, Danny Azucar, Paola De Bernardi, and Danny Azucar. 2020. Innovation and entrepreneurial ecosystems: Structure, boundaries, and dynamics. In Innovation in Food Ecosystems. Contributions to Management Science. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte. 2013. Economic Impact Assessment of the Proposed European General Data Protection Regulation. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/uk/Documents/about-deloitte/deloitte-uk-european-data-protection-tmt.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2019).

- Elia, Gianluca, Alessandro Margherita, and Giuseppina Passiante. 2020. Digital entrepreneurship ecosystem: How digital technologies and collective intelligence are reshaping the entrepreneurial process. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 150: 119791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUIPO. 2021. Intellectual Property Rights and Firm Performance in the European Union. Available online: https://euipo.europa.eu/tunnel-web/secure/webdav/guest/document_library/observatory/documents/reports/IPContributionStudy/IPR_firm_performance_in_EU/2021_IP_Rights_and_firm_performance_in_the_EU_en.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Fernandes, Cristina, João J. Ferreira, Pedro Mota Veiga, Sascha Kraus, and Marina Dabić. 2022. Digital entrepreneurship platforms: Mapping the field and looking towards a holistic approach. Technology in Society 70: 101979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawer, Annabelle. 2022. Digital platforms and ecosystems: Remarks on the dominant organizational forms of the digital age. Innovation: Organization and Management 24: 110–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GEDI. 2020. The Digital Platform Economy Index 2020. Available online: https://thegedi.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/DPE-2020-Report-Final.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Gigauri, Iza, Simona-Andreea Apostu, and Catalin Popescu. 2023. Digital transformation: Threats and opportunities for social entrepreneurship. In Two Faces of Digital Transformation: Technological Opportunities versus Social Threats. Bradford: Emerald Group Publishing Ltd., pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, Sofia, and João M. Lopes. 2022. ICT access and entrepreneurship in the open innovation dynamic context: Evidence from OECD countries. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 8: 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, Sofia, and João M. Lopes. 2023. The Transformational Impact of Digital Venture Ecosystems on Entrepreneurship in Europe. In Bleeding-Edge Entrepreneurship: Digitalization, Blockchains, Space, the Ocean, and Artificial Intelligence. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited, pp. 91–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyedu, Samuel, Heng Tang, Michael Verner Menyah, and George Duodu Kissi. 2024. The relationship between intellectual property rights, innovation, and economic development in the G20 and selected developing countries. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasani, Tahereh, Norman O’Reilly, Ali Dehghantanha, Davar Rezania, and Nadège Levallet. 2023. Evaluating the adoption of cybersecurity and its influence on organizational performance. SN Business & Economics 3: 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2018. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs 85: 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzmann, Patrick, and Patrick Gregori. 2023. The promise of digital technologies for sustainable entrepreneurship: A systematic literature review and research agenda. International Journal of Information Management 68: 102593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Hao, Lindong Wang, and Yang Shi. 2022. How does the institutional environment in the digital context affect technology entrepreneurship? The moderating roles of government digitalization and gender. Journal of Organizational Change Management 35: 1089–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasim, Raja Suzana Raja, Nurul Afiqah Zulazli, Wan Fariza Azima Che Azman, and Rooshihan Merican B. Abdul Rahim Merican. 2024. The mediating effect of technology adoption in the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and sustainable entrepreneurship values among Fintech organizations in Malaysia. International Journal of Religion 5: 476–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kergroach, Sandrine. 2021. SMEs Going Digital: Policy Challenges and Recommendations. OECD Going Digital Toolkit Notes, No. 15. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koomson, Isaac, Edward Martey, and Prince M. Etwire. 2023. Mobile money and entrepreneurship in East Africa: The mediating roles of digital savings and access to digital credit. Information Technology and People 36: 996–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, Sascha, Carolin Palmer, Norbert Kailer, Friedrich Lukas Kallinger, and Jonathan Spitzer. 2019. Digital entrepreneurship: A research agenda on new business models for the twenty-first century. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research 25: 353–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Yan Yin, Mohammad Falahat, and Bik Kai Sia. 2021. Drivers of digital adoption: A multiple case analysis among low and high-tech industries in Malaysia. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration 13: 80–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Jiahui, and Meifang Yao. 2021. New framework of digital entrepreneurship model based on artificial intelligence and cloud computing. Mobile Information Systems 2021: 3080160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linzalone, Roberto, Giovanni Schiuma, and Salvatore Ammirato. 2020. Connecting universities with entrepreneurship through digital learning platform: Functional requirements and education-based knowledge exchange activities. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research 26: 1525–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Sheng, Sierdjan Koster, and Xiuying Chen. 2022. Digital divide or dividend? The impact of digital finance on the migrants’ entrepreneurship in less developed regions of China. Cities 131: 103896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Yang, Jiuyu Dong, Liang Mei, and Rui Shen. 2023. Digital innovation and performance of manufacturing firms: An affordance perspective. Technovation 119: 102458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lythreatis, Sophie, Sanjay Kumar Singh, and Abdul-Nasser El-Kassar. 2022. The digital divide: A review and future research agenda. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 175: 121359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manimala, Mathew J., Princy Thomas, and P. K. Thomas. 2019. Perception of entrepreneurial ecosystem: Testing the actor–observer bias. Journal of Entrepreneurship 28: 316–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Nicholas, Christian Matt, Crispin Niebel, and Knut Blind. 2019. How data protection regulation affects startup innovation. Information Systems Frontiers 21: 1307–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michota, Alexandra. 2013. Digital security concerns and threats facing women entrepreneurs. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship 2: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkansi, Marcia. 2022. E-business adoption costs and strategies for retail micro businesses. Electronic Commerce Research 22: 1153–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, Jonathan, Wyn Morris, and Robert Bowen. 2022. Implications of the digital divide on rural SME resilience. Journal of Rural Studies 89: 369–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, Tayyab, Muhammad Tahir Munir, Muhammad Zubair Munir, and Muhammad Waleed Zafar. 2018. Elevating business operations: The transformative power of cloud computing. International Journal of Computer Science and Technology 2: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan, Vivek S., Satyanarayana Parayitam, and Tejinder Sharma. 2012. The relationship between web quality and user satisfaction: The moderating effects of security and content. International Journal of Business Excellence 5: 52–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Thu Thuy, Thi Ngoc Hoai Tran, Thi Huyen My Do, Thi Khanh Linh Dinh, Thi Uyen Nhi Nguyen, and Tran Minh Khue Dang. 2024. Digital literacy, online security behaviors and E-payment intention. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 10: 100292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunmuyiwa, Michael, and Olasunkanmi Amida. 2022. The nexus between electronic payment system and entrepreneurial activities in rural areas of Ogun State, Nigeria. Przedsiębiorczość-Edukacja 18: 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orser, Barbara, Allan Riding, and Yanhong Li. 2019. Technology adoption and gender-inclusive entrepreneurship education and training. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship 11: 273–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, Saurav, Emanuel Xavier-Oliveira, and André O. Laplume. 2013. Influence of intellectual property, foreign investment, and technological adoption on technology entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Research 66: 2090–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, Justin, Ibrahim Alhassan, Nasser Binsaif, and Prakash Singh. 2023. Digital entrepreneurship research: A systematic review. Journal of Business Research 156: 113507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, Leandro, Yuliya Tovstolyak, Renato Lopes da Costa, Álvaro Dias, and Rui Gonçalves. 2023. Internationalisation business strategy via e-commerce. International Journal of Business and Systems Research 17: 225–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petti, Claudio, and Shujun Zhang. 2011. Factors influencing technological entrepreneurship capabilities: Towards an integrated research framework for Chinese enterprises. Journal of Technology Management in China 6: 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipitwanichakarn, Tanikan, and Nittaya Wongtada. 2020. The role online review on mobile commerce adoption: An inclusive growth context. Journal of Asia Business Studies 14: 759–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proksch, Dorian, Anna Frieda Rosin, Stephan Stubner, and Andreas Pinkwart. 2024. The influence of a digital strategy on the digitalization of new ventures: The mediating effect of digital capabilities and digital culture. Journal of Small Business Management 62: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddick, Christopher G., Roger Enriquez, Richard J. Harris, and Bonita Sharma. 2020. Determinants of broadband access and affordability: An analysis of a community survey on the digital divide. Cities 106: 102904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringle, Christian M., Sven Wende, and Jan-Michael Becker. 2024. SmartPLS 4. Bönningstedt: SmartPLS. Available online: https://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- Sahut, Jean-Michel, Luca Iandoli, and Frédéric Teulon. 2021. The age of digital entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics 56: 1159–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satalkina, Liliya, and Gerald Steiner. 2020. Digital entrepreneurship and its role in innovation systems: A systematic literature review as a basis for future research avenues for sustainable transitions. Sustainability 12: 2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, Dean A., and Ann Majchrzak. 2022. Machines augmenting entrepreneurs: Opportunities (and threats) at the Nexus of artificial intelligence and entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing 37: 106227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheriff, Michael, and Moreno Muffatto. 2015. The present state of entrepreneurship ecosystems in selected countries in Africa. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies 6: 17–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soluk, Jonas, Nadine Kammerlander, and Solomon Darwin. 2021. Digital entrepreneurship in developing countries: The role of institutional voids. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 170: 120876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steininger, Dennis M. 2019. Linking information systems and entrepreneurship: A review and agenda for IT-associated and digital entrepreneurship research. Information Systems Journal 29: 363–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steininger, Dennis M., M. Kathryn Brohman, and Jörn H. Block. 2022. Digital entrepreneurship: What is new if anything? Business and Information Systems Engineering 641: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussan, Fiona, and Zoltan J. Acs. 2017. The digital entrepreneurial ecosystem. Small Business Economics 49: 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, George F. IV, Scott Weaven, Helen Perkins, Deepak Sardana, and Robert W. Palmatier. 2018. International market entry strategies: Relational, digital, and hybrid approaches. Journal of International Marketing 26: 30–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Chih-Hai, Yi-Ju Huang, and Hsuan-Yu Lin. 2014. Do stronger intellectual property rights induce more innovations? A cross-country analysis. Hitotsubashi Journal of Economics 55: 167–88. [Google Scholar]

- Yeganegi, Sepideh, André O. Laplume, and Parshotam Dass. 2021. The role of information availability: A longitudinal analysis of technology entrepreneurship. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 170: 120910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, Shaker A., Wan Liu, and Steven Si. 2023. How digital technology promotes entrepreneurship in ecosystems. Technovation 119: 102457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Jianhong, Désirée van Gorp, and Henk Kievit. 2023. Digital technology and national entrepreneurship: An ecosystem perspective. Journal of Technology Transfer 48: 1077–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Xiaoyang, and Zongyuan Weng. 2024. Digital dividend or divide: The digital economy and urban entrepreneurial activity. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences 93: 101857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).