Gen Z Employee Adaptive Performance: The Role of Inclusive Leadership and Workplace Happiness

Abstract

1. Introduction

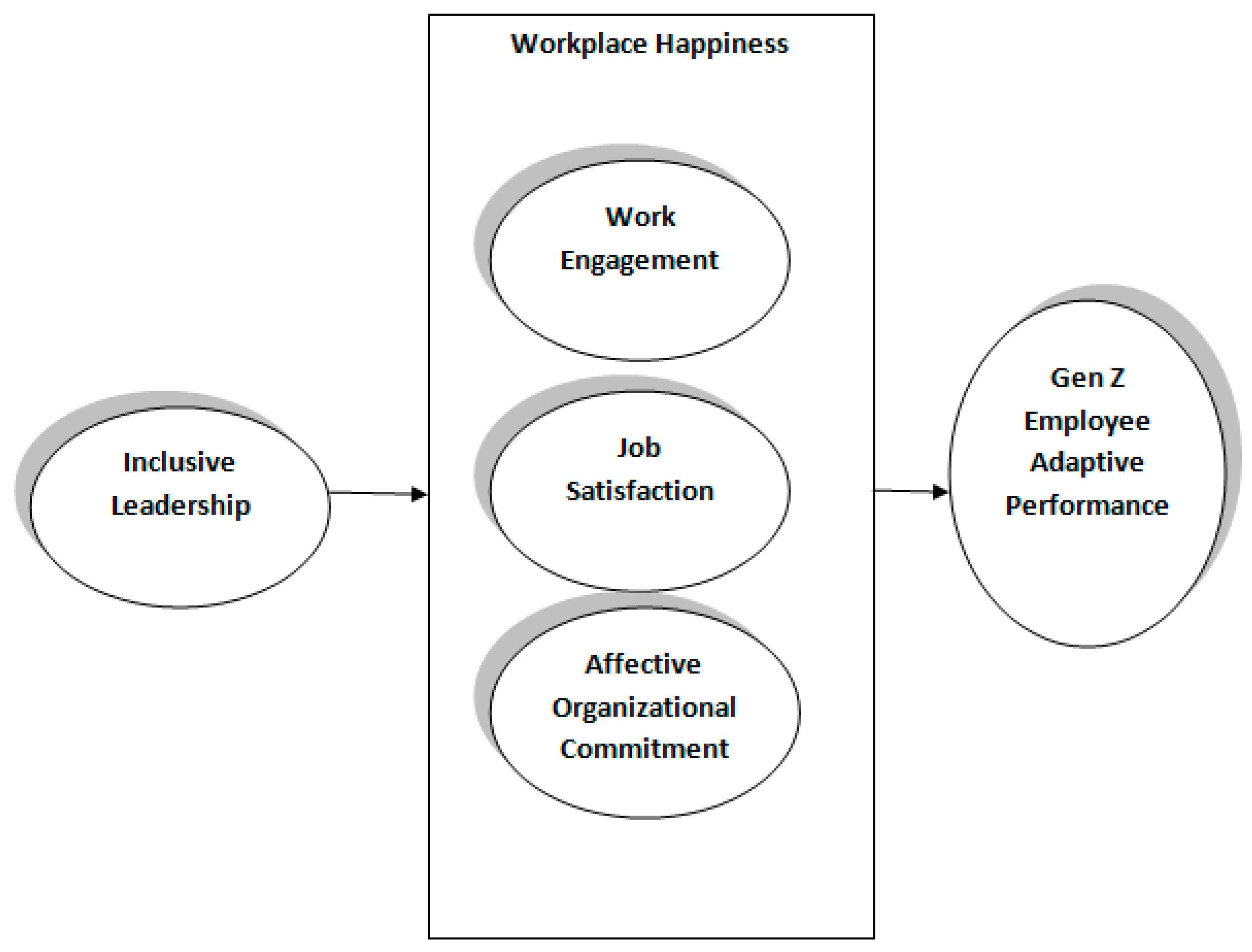

2. Inclusive Leadership and Adaptive Performance

3. The Mediating Role of Workplace Happiness

4. Results

4.1. Direct Effects

4.2. Mediation Effects

5. Methods

5.1. Procedure and Participants

5.2. Measures

6. Discussion

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adams, Byron, Christina Meyers, and Sekaja Lusanda. 2020. Positive Leadership: Relationships with Employee Inclusion, Discrimination, and Well-Being. Applied Psychology 69: 1145–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, Blake, Cassondra Batz-Barbarich, Haley Sterling, and Louis Tay. 2019. Outcomes of Meaningful Work: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Management Studies 56: 500–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashikali, Tanachia, Sandra Groeneveld, and Ben Kuipers. 2021. The Role of Inclusive Leadership in Supporting an Inclusive Climate in Diverse Public Sector Teams. Review of Public Personnel Administration 41: 497–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannay, Dheyaa Falih, Mohammed Jabbar Hadi, and Ahmed Abdullah Amanah. 2020. The Impact of Inclusive Leadership Behaviors on Innovative Workplace Behavior with an Emphasis on the Mediating Role of Work Engagement. Problems and Perspectives in Management 18: 479–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataineh, Mohammad Saleh Enaizan, Siti-Rohaida Mohamed Zainal, Rajendran Muthuveloo, Raheel Yasin, Joather Al Wali, and Mohamed Ibrahim Mugableh. 2022. Impact of Inclusive Leadership on Adaptive Performance: The Role of Innovative Work Behavior. International Journal of Business Science & Applied Management 17: 28–43. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, Peter. 1964. Exchange and Power in Social Life. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Bowling, Nathan, Steve Khazon, Rustin Meyer, and Carla Burrus. 2015. Situational Strength as a Moderator of the Relationship Between Job Satisfaction and Job Performance: A Meta-Analytic Examination. Journal of Business and Psychology 30: 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brokmeier, Luisa Leonie, Catherin Bosle, Joachim Fischer, and Raphael Herr. 2022. Associations Between Work Characteristics, Engaged Well-Being at Work, and Job Attitudes—Findings from a Longitudinal German Study. Safety and Health at Work 13: 213–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmeli, Abraham, Roni Reiter-Palmon, and Enbal Ziv. 2010. Inclusive Leadership and Employee Involvement in Creative Tasks in the Workplace: The Mediating Role of Psychological Safety. Creativity Research Journal 22: 250–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnevale, Joel, Lei Huang, Marcus Crede, Peter Harms, and Mary Uhl-Bien. 2017. Leading to Stimulate Employees’ Ideas: A Quantitative Review of Leader–Member Exchange, Employee Voice, Creativity, and Innovative Behavior. Applied Psychology: An International Review 66: 517–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenkci, Ada Tuna, Tuba Bircan, and Jeff Zimmerman. 2021. Inclusive Leadership and Work Engagement: The Mediating Role of Procedural Justice. Management Research Review 44: 158–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Lu, Fan Luo, Xiaomei Zhu, Xinjian Huang, and Yanhong Liu. 2020. Inclusive Leadership Promotes Challenge-Oriented Organizational Citizenship Behavior through the Mediation of Work Engagement and Moderation of Organizational Innovative Atmosphere. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 560594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Suk Bong, Thi Bich Hanh Tran, and Byung II Park. 2015. Inclusive Leadership and Work Engagement: Mediating Roles of Affective Organizational Commitment and Creativity. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal 43: 931–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Suk Bong, Thi Bich Hanh Tran, and Seung-Wan Kang. 2017. Inclusive Leadership and Employee Well-Being: The Mediating Role of Person-Job Fit. Journal of Happiness Studies 18: 1877–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csiszárik-Kocsír, Ágnes, and Mónika Garia-Fodor. 2018. Motivation Analysing and Preference System of Choosing a Workplace as Segmentation Criteria Based on a Country Wide Research Result Focus on Generation of Z. On-Line Journal Modelling the New Europe 27: 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, Kristin L., Bryan D. Edwards, Wm Camron Casper, and Kevin R. Gue. 2014. Employees’ Adaptability and Perceptions of Change-Related Uncertainty: Implications for Perceived Organizational Support, Job Satisfaction, and Performance. Journal of Business and Psychology 29: 269–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahleez, Khalid Abed, Mohammed Aboramadan, and Fadi Abdelfattah. 2023. Inclusive Leadership and Job Satisfaction in Omani Higher Education: The Mediation of Psychological Ownership and Employee Thriving. International Journal of Educational Management 37: 907–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLeon, Haley. 2023. How to Increase Employee Job Satisfaction. Available online: https://corporatetraining.usf.edu/blog/how-to-increase-employee-job-satisfaction (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Errida, Abdelouahab, and Bouchra Lotfi. 2021. The Determinants of Organizational Change Management Success: Literature Review and Case Study. International Journal of Engineering Business Management 13: 184797902110162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, Tasneem, Mehwish Majeed, and Syed Zulfiqar Ali Shah. 2021. A Moderating Mediation Model of the Antecedents of Being Driven to Work: The Role of Inclusive Leaders as Change Agents. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne des Sciences de L’administration 38: 257–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, Cynthia. 2010. Happiness at work. International Journal of Management Reviews 12: 384–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garba, Omale, Babalola Babalola, and Guo Liang. 2017. A Social Exchange Perspective on Why and When Ethical Leadership Foster Customer-Oriented Citizenship Behavior. International Journal of Hospitality Management 70: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, Paul, Eli Finkel, Grainne Fitzsimons, and Francesca Gino. 2017. The Energizing Nature of Work Engagement: Toward a New Need-Based Theory of Work Motivation. Research in Organizational Behavior 37: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, Mark, Andrew Neal, and Sharon Parker. 2007. A New Model of Work Role Performance: Positive Behavior in Uncertain and Interdependent Contexts. Academy of Management Journal 50: 327–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyekye, Seth Ayim, and Mohammad Haybatollahi. 2015. Organizational citizenship behaviour: An empirical investigation of the impact of age and job satisfaction on Ghanaian industrial workers. International Journal of Organizational Analysis 23: 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph, Rolph Anderson, Ronald Tatham, and William Black. 1998. Multivariate Data Analysis. Upper Saddle River: Prentice-Hall International. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, Stevan, Jonathon Halbesleben, Jean-Pierre Neveu, and Mina Westman. 2018. Conservation of Resources in the Organizational Context: The Reality of Resources and Their Consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 5: 103–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobucci, Dawn. 2010. Structural Equations Modeling: Fit Indices, Sample Size, and Advanced Topics. Journal of Consumer Psychology 20: 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Nazmul. 2023. Managing Organizational Change in Responding to Global Crises. Global Business and Organizational Excellence 42: 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, Timothy, Carl Thoresen, Joyce Bono, and Gregory Patton. 2001. The Job Satisfaction–Job Performance Relationship: A Qualitative and Quantitative Review. Psychological Bulletin 127: 376–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judge, Timothy, Howard Weiss, John Kammeyer-Mueller, and Charles Hulin. 2017. Job Attitudes, Job Satisfaction, and Job Affect: A Century of Continuity and of Change. Journal of Applied Psychology 102: 356–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsaros, Kleanthis. 2022. Exploring the Inclusive Leadership and Employee Change Participation Relationship: The Role of Workplace Belongingness and Meaning-Making. Baltic Journal of Management 17: 158–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsaros, Kleanthis. 2024. Firm Performance in the Midst of the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Perceived Organizational Support during Change and Work Engagement. Employee Relations 46: 622–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsaros, Kleanthis, and Athanasios Tsirikas. 2022. Perceived Change Uncertainty and Behavioral Change Support: The Role of Positive Change Orientation. Journal of Organizational Change Management 35: 511–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, Bahar, and Osman Karatepe. 2020. Does Servant Leadership Better Explain Work Engagement, Career Satisfaction and Adaptive Performance than Authentic Leadership? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 32: 2075–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Minseo, and Terry A. Beehr. 2020. Empowering Leadership: Leading People to be Present through Affective Organizational Commitment? The International Journal of Human Resource Management 31: 2017–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kun, Agota, and Peter Gadanecz. 2022. Workplace Happiness, Well-Being and Their Relationship with Psychological Capital: A Study of Hungarian Teachers. Current Psychology 41: 185–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Huiqian, and Cheng Zhou. 2023. The Influence Mechanisms of Inclusive Leadership on Job Satisfaction: Evidence from Young University Employees in China. PLoS ONE 18: e0287678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luu, Trong Tuan. 2019. The Well-Being among Hospitability Employees with Disabilities: The Role of Disability Inclusive Benevolent Leadership. International Journal of Hospitality Management 80: 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, Robert, Michael Browne, and Hazuki Sugawara. 1996. Power Analysis and Determination of Sample Size for Covariance Structure Modeling. Psychological Methods 1: 130–49. [Google Scholar]

- Marques-Quinteiro, Pedro, Ricardo Vargas, Nicole Eifler, and Luís Curral. 2019. Employee Adaptive Performance and Job Satisfaction during Organizational Crisis: The Role of Self-Leadership. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 28: 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, Vineetha Sarju. 2023. Happiness a Driver for Innovation at the Workplace. In Understanding Happiness: An Explorative View. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, pp. 335–44. [Google Scholar]

- Matthysen, Megan, and Chantel Harris. 2018. The Relationship Between Readiness to Change and Work Engagement: A Case Study in an Accounting Firm Undergoing Change. SA Journal of Human Resource Management 16: 11. [Google Scholar]

- McAllister, Sean. 2024. How is Gen Z Changing the Workplace? Available online: https://www.zurich.com/en/media/magazine/2022/how-will-gen-z-change-the-future-of-work#:~:text=Born%20between%201995%20and%202009,attract%20and%20retain%20new%20talent (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- Mousa, Mohamed, Hiba Massoud, and Rami Ayoubi. 2020. Gender, Diversity Management Perceptions, Workplace Happiness and Organisational Citizenship Behavior. Employee Relations 42: 1249–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowday, Richard, Steers Richard, and Lyman Porter. 1979. The Measurement of Organizational Commitment. Journal of Vocational Behavior 14: 224–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujajati, Ester, Nadia Ferreira, and Melissa Du Plessis. 2024. Fostering Organisational Commitment: A Resilience Framework for Private-Sector Organisations in South Africa. Frontiers in Psychology 15: 1303866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuber, Lina, Colinda Englitz, Niklas Schulte, Boris Forthmann, and Heinz Holling. 2022. How Work Engagement Relates to Performance and Absenteeism: A Meta-Analysis. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 31: 292–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Thi Ngoc Linh. 2024. The Influence of Establishing a Happy Workplace Environment on Attracting Generation Z. Educational Administration: Theory and Practice 30: 2482–88. [Google Scholar]

- Nishii, Lisa, and Hannes Leroy. 2022. A Multi-Level Framework of Inclusive Leadership in Organizations. Group & Organization Management 47: 683–722. [Google Scholar]

- Obuobisa-Darko, Theresa. 2020. Ensuring Employee Task Performance: Role of Employee Engagement. Performance Improvement 59: 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2022. Employment Outlook 2022. Available online: https://oecd.org/employment-outlook/2022/ (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Okros, Alan. 2020. Generational Theory and Cohort Analysis, Management for Professionals. In Harnessing the Potential of Digital Post-Millennials in the Future Workplace. vols. 2. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland AG, pp. 33–51. [Google Scholar]

- Oreg, Shaul, Alexandra Michel, and Rune Todnem By. 2023. The Psychology of Organizational Change: New Insights on the Antecedents and Consequences on The Individual’s Responses To Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Sohee, and Sunyoung Park. 2019. Employee Adaptive Performance and Its Antecedents: Review and Synthesis. Human Resource Development Review 18: 294–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Jian, Mingze Li, Zhen Wang, and Yuying Lin. 2021. Transformational Leadership and Employees’ Reactions to Organizational Change: Evidence from a Meta-Analysis. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 57: 369–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichler, Shaun, Chiranjeev Kohli, and Neil Granitz. 2021. DITTO for Gen Z: A Framework for Leveraging the Uniqueness of the New Generation. Business Horizons 64: 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, Philip, Scott MacKenzie, Jeong-Yeon Lee, and Nathan Podsakoff. 2003. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology 88: 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Lei, Bing Liu, Xin Wei, and Yanghong Hu. 2019. Impact of Inclusive Leadership on Employee Innovative Behavior: Perceived Organizational Support as a Mediator. PLoS ONE 14: e0212091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qing, Miao, Muhammad Asif, Abid Hussain, and Arif Jameel. 2019. Exploring the Impact of Ethical Leadership on Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment in Public Sector Organizations: The Mediating Role of Psychological Empowerment. Review of Managerial Science 11: 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureos. 2024. 20+ Gen Z Statistics for Employers. Available online: https://www.qureos.com/hiring-guide/gen-z-statistics#what-is-generation-z (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Qurrahtulain, Khan, Tayyaba Bashir, Iftikhar Hussain, Shakeel Ahmed, and Aamir Nisar. 2022. Impact of Inclusive Leadership on Adaptive Performance with the Mediation of Vigor at Work and Moderation of Internal Locus of Control. Journal of Public Affairs 22: e2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, Sahar, Ishfaq Ahmed, and Gulnaz Shahzadi. 2022. Linking Workplace Spirituality and Adaptive Performance through a Serial Mediation of Job Satisfaction and Emotional Labor Strategies. Management Research Review 45: 1354–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randel, Amy E., Benjamin M. Galvin, Lynn M. Shore, Karen Holcombe Ehrhart, Beth G. Chung, Michelle A. Dean, and Uma Kedharnath. 2018. Inclusive Leadership: Realizing Positive Outcomes through Belongingness and Being Valued for Uniqueness. Human Resource Management Review 28: 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, Bruce Louis, Jeffrey LePine, and Eean Crawford. 2010. Job Engagement: Antecedents and Effects on Job Performance. Academy of Management Journal 53: 617–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, Pablo, Claudio Aqueveque, and Ignacio J. Duran. 2019. Do Employees Value Strategic Csr? A Tale of Affective Organizational Commitment and its Underlying Mechanisms. Business Ethics: A European Review 28: 459–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, Wilmar, Marisa Salanova, Vicente González Romá, and Arnold Bakker. 2002. The Measurement of Engagement and Burnout: A Two Sample Confirmatory Factor Analytic Approach. Journal of Happiness Studies 3: 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaumberg, Rebecca, and Francis Flynn. 2017. Clarifying the Link between Job Satisfaction and Absenteeism: The Role of Guilt Proneness. Journal of Applied Psychology 102: 982–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Naman, and Vinod Singh. 2016. Effect of Workplace Incivility on Job Satisfaction and Turnover Intentions in India. South Asian Journal of Global Business Research 5: 234–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, Lynn, and Beth Chung. 2022. Inclusive Leadership: How Leaders Sustain Or Discourage Work Group Inclusion. Group & Organization Management 47: 723–54. [Google Scholar]

- Shore, Lynn M., Jeanette N. Cleveland, and Diana Sanchez. 2018. Inclusive Workplaces: A Review and Model. Human Resource Management Review 28: 176–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sony, Michael, and Nandakumar Mekoth. 2016. The Relationship between Emotional Intelligence, Frontline Employee Adaptability, Job Satisfaction and Job Performance. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 30: 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, Paul. 1997. Job Satisfaction: Application, Assessment, Cause and Consequences. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Stater, Keely Jones, and Mark Stater. 2019. Is It “Just Work”? The Impact of Work Rewards on Job Satisfaction and Turnover Intent in the Nonprofit, For-Profit, and Public Sectors. The American Review of Public Administration 49: 495–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, Daniel, Nick Hobson, Jon M. Jachimowicz, and Ashley Whillans. 2021. How Companies Can Improve Employee Engagement Right Now. Available online: https://hbr.org/2021/10/how-companies-can-improve-employee-engagement-right-now (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Stone-Romero, Eugene, and Patrick Rosopa. 2008. The Relative Validity of Inferences about Mediation as a Function of Research Design Characteristics. Organizational Research Methods 11: 326–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, Karoline, Mark A. Griffin, Sharon K. Parker, and Claire M. Mason. 2015. Building and Sustaining Proactive Behaviors: The Role of Adaptivity and Job Satisfaction. Journal of Business and Psychology 30: 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umrani, Waheed Ali, Alexandre Anatolievich Bachkirov, Asif Nawaz, Umair Ahmed, and Munwar Hussain Pahi. 2024. Inclusive Leadership, Employee Performance and Well-Being: An Empirical Study. Leadership & Organization Development Journal 45: 231–50. [Google Scholar]

- UNCTAD. 2021. Digital Economy Report 2021, Cross-Border Data Flows and Development: For Whom the Data Flow. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/der2021_en.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Vakira, Elton, Ngoni CourageShereni, Chantelle Ncube, and Njabulo Ndlovu. 2023. The Effect of Inclusive Leadership on Employee Engagement, Mediated by Psychological Safety in the Hospitality Industry. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights 6: 819–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakola, Maria, Paraskevas Petrou, and Kleanthis Katsaros. 2021. Work Engagement and Job Crafting as Conditions of Ambivalent Employees’ Adaptation to Organizational Change. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 57: 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vito, Rosemary, Alice Schmidt Hanbidge, and Laura Brunskill. 2023. Leadership and Organizational Challenges, Opportunities, Resilience, and Supports during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance 47: 83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Jacob, Jihye Oh, Jiwon Park, and Woocheol Kim. 2020. The Relationship between Work Engagement and Work-Life Balance in Organizations: A Review of the Empirical Research. Human Resource Development Review 19: 240–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Hao, Zhao Lijing, and Yixuan Zhao. 2020. Inclusive Leadership and Taking-Charge Behavior: Roles of Psychological Safety and Thriving at Work. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Junting, Mudaser Javaid, Shudi Liao, Myeongcheol Choi, and Hann Earl Kim. 2024. How and When Humble Leadership Influences Employee Adaptive Performance? The Roles of Self-Determination and Employee Attributions. Leadership & Organization Development Journal 45: 377–96. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Mean | SD | Alpha | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | E.Gender (C) | 1.25 | 0.32 | - | ||||||||

| 2. | E.AgeGroup (C) | 1.65 | 0.78 | 0.62 * | - | |||||||

| 3. | E.Education (C) | 2.15 | 0.61 | 0.52 * | −0.42 * | - | ||||||

| 4. | Inclusive leadership (E) | 3.98 | 1.02 | 0.82 | 0.45 ** | 0.21 | 0.08 | - | ||||

| 5. | Work engagement (E) | 3.64 | 1.11 | 0.88 | 0.65 | 0.77 | 0.37 | 0.78 ** | - | |||

| 6. | Job satisfaction (E) | 3.22 | 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.32 | 0.71 * | 0.85 | 0.64 * | 0.78 * | - | ||

| 7. | Affective organizational commitment (E) | 3.01 | 0.87 | 0.78 | 0.78 * | 0.65 | 0.45 * | 0.66 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.51 * | - | |

| 8. | Adaptive performance (S) | 3.44 | 0.68 | 0.91 | 0.32 | 0.58 | 0.78 | 0.85 ** | 0.08 * | 0.22 * | 0.01 * | - |

| Variables | AP | WE | JS | AOC | AP | AP | AP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Constant) | 1.45 | 1.14 | 0.11 | 2.14 | 0.25 | 1.27 | 2.71 |

| Inclusive leadership (IL) | 0.79 ** | 0.89 ** | 0.78 ** | 0.08 * | |||

| Work engagement (WE) | 0.42 ** | ||||||

| Job satisfaction (JS) | 0.36 ** | ||||||

| Affective organizational commitment (AOC) | 0.22 * | ||||||

| Gender | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.12 | −0.18 | 0.04 | −0.05 |

| Age | 0.05 * | 0.25 | −0.88 | −0.38 | 0.05 | 0.24 | −0.51 |

| Education | 0.25 ** | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.32 | 0.31 | 0.22 | 0.59 |

| R2 | 0.45 ** | 0.36 * | 0.41 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.38 * | 0.36 ** | 0.24 * |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.54 | 0.42 | 0.48 | 0.31 | 0.36 | 0.41 | 0.28 |

| Model Fit | Mediated Model | Cutoff Point | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normed Chi-Square, χ2/d.f. | 1.777 | <3 | Qing et al. (2019) |

| Standardized Root-Mean-Square Residual (SRMR) | 0.002 | <0.05 | Iacobucci (2010) |

| Goodness of Fitindex (GFI) | 0.989 | >0.95 | Hair et al. (1998) |

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | 0.988 | >0.95 | Hair et al. (1998) |

| Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) | 0.050 | <0.06 | Iacobucci (2010) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Katsaros, K.K. Gen Z Employee Adaptive Performance: The Role of Inclusive Leadership and Workplace Happiness. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14080163

Katsaros KK. Gen Z Employee Adaptive Performance: The Role of Inclusive Leadership and Workplace Happiness. Administrative Sciences. 2024; 14(8):163. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14080163

Chicago/Turabian StyleKatsaros, Kleanthis K. 2024. "Gen Z Employee Adaptive Performance: The Role of Inclusive Leadership and Workplace Happiness" Administrative Sciences 14, no. 8: 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14080163

APA StyleKatsaros, K. K. (2024). Gen Z Employee Adaptive Performance: The Role of Inclusive Leadership and Workplace Happiness. Administrative Sciences, 14(8), 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14080163