1. Introduction

Entrepreneurship is widely seen as a key driving force in any country’s economic growth, employment opportunities, and innovation. Moreover, entrepreneurship is generally considered the main driver of social innovation and economic growth of a country (

Holloway and Pimlott-Wilson 2021;

Talukder and Lakner 2023). That is true for Bangladesh as well. Bangladesh, a south Asian country, has a total population of 165.16 million, with 20% of that made up of young adults (age 15–24) (

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics 2022). It is worth noting that the overall unemployment rate in the country is experiencing a gradual increase. Specifically, the young unemployment rate in Bangladesh stands at 12.93% (

Statista n.d.a,

n.d.b). This problem highlights the fact that the people of Bangladesh, especially the younger generation, cannot depend exclusively on the government and corporations for employment but rather must start their own businesses to survive (

Shahriar et al. 2021). Since entrepreneurship is regarded as a key driver of economic growth, innovation, and job creation, it is one of the most popular alternative solutions for tackling unemployment issues. However, unemployment among Bangladeshi university graduates is a serious problem on a national scale (

Rahaman et al. 2020). So, there is a growing need for entrepreneurship in Bangladesh to address the issue of youth unemployment (

AI Saiqal et al. 2019). The government of Bangladesh is aiming to foster an entrepreneurial environment by offering financial support to the younger generation so that the country’s economy can grow overall (

Startup Bangladesh Limited n.d.). However, university graduates in Bangladesh believe it is better to work for the government or other organizations instead of starting their own businesses (

Karmoker et al. 2020). There has been a parallel rise in both the rate of unemployment and the number of university graduates in recent years (

Uddin et al. 2022). Unfortunately, the current job market is not ready to employ all the country’s university grads, which is leading to economic inequality (

Rahman et al. 2022). Hence, entrepreneurship and self-employment, in this context, can provide graduates with promising career paths that help to propel the socioeconomic development of the nation. A great deal of research has focused on the underlying factors of entrepreneurship intention and how it affects the development of an economy, especially in the case of youngsters (

Ogunsade et al. 2021).

The process of entrepreneurial activity begins with an individual’s entrepreneurial intention. For someone who wants to start a new venture, their entrepreneurial intentions are very important because it show the way they think, which guides their actions and decisions (

Bird 1988;

Krueger et al. 2000;

Shapero and Sokol 1982). Moreover, an entrepreneurial intention is a way of thinking that guides one’s focus, knowledge, and actions in the direction of a specific objective. It is the primary determinant of an individual’s actions that can motivate individuals to become entrepreneurs (

Ozaralli and Rivenburgh 2016). Still, practically every nation faces the problem of how to foster an entrepreneurial spirit and alter individual perceptions toward entrepreneurship (

Shah et al. 2020). Universities are key players in creating and growing an economy based on entrepreneurship (

Talukder et al. 2024). Furthermore, it is widely acknowledged that entrepreneurship education provided by the university plays a significant role in assisting students in comprehending and cultivating entrepreneurial intention (

Lv et al. 2021). Entrepreneurs with higher levels of education also have a better chance of making a positive impact on the local economy compared to those with lower levels of education (

Taatila 2010). On the other hand, important personality traits that influence students’ intentions to start their own enterprise include the need for achievement and a risk-taking propensity (

Brockhaus 1980;

Murray and McAdams 2007). Moreover, risk-taking propensity can change attitudes toward entrepreneurship (

Chanda and Unel 2021). A higher degree of entrepreneurial intention is associated with a higher risk tolerance (

Hmieleski and Corbett 2006). Individuals with a strong need for achievement are more likely to engage in creative and innovative activities, such as entrepreneurship, that entail an individual’s responsibility for task outcomes than those with a low need for achievement (

McClelland 1961). The factors that shape students’ intentions to start their own businesses should be understood. This is because decision-makers can learn what inspires youngsters to pursue entrepreneurial careers. Likewise, the improvement in the economy has encouraged researchers to focus on this aspect of entrepreneurship (

Rahman et al. 2017).

Entrepreneurial activities take time to flourish (

Zamrudi and Yulianti 2020). Furthermore, it involves the interaction of cognitive processes and behavioral attitudes with socioeconomic and cultural influences. Previous research has confirmed that persons with a strong and positive entrepreneurial intention (EI) have a high potential for entrepreneurship (

Ozaralli and Rivenburgh 2016;

Sampene et al. 2022). The relationship between the theory of planned behavior and entrepreneurial intention proposed by

Ajzen (

1991) assumes personal attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control as antecedents of entrepreneurial intention. In this study, researchers consider risk-taking propensity, entrepreneurship education support, and the need for achievement as antecedents of the theory of planned behavior model, as they influence attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. A high risk-taking propensity promotes positive attitudes toward entrepreneurship and increases confidence in handling uncertainties (

Hmieleski and Corbett 2006). On the other hand, entrepreneurship education has a positive impact on attitudes, fosters a supportive social environment, and increases confidence by providing skills and knowledge (

Ozaralli and Rivenburgh 2016). More importantly, a strong need for achievement drives individuals to reach difficult goals, promotes positive attitudes, and boosts self-efficacy (

Tessema Gerba 2012). These elements influence the TPB framework’s predictions about entrepreneurial intention.

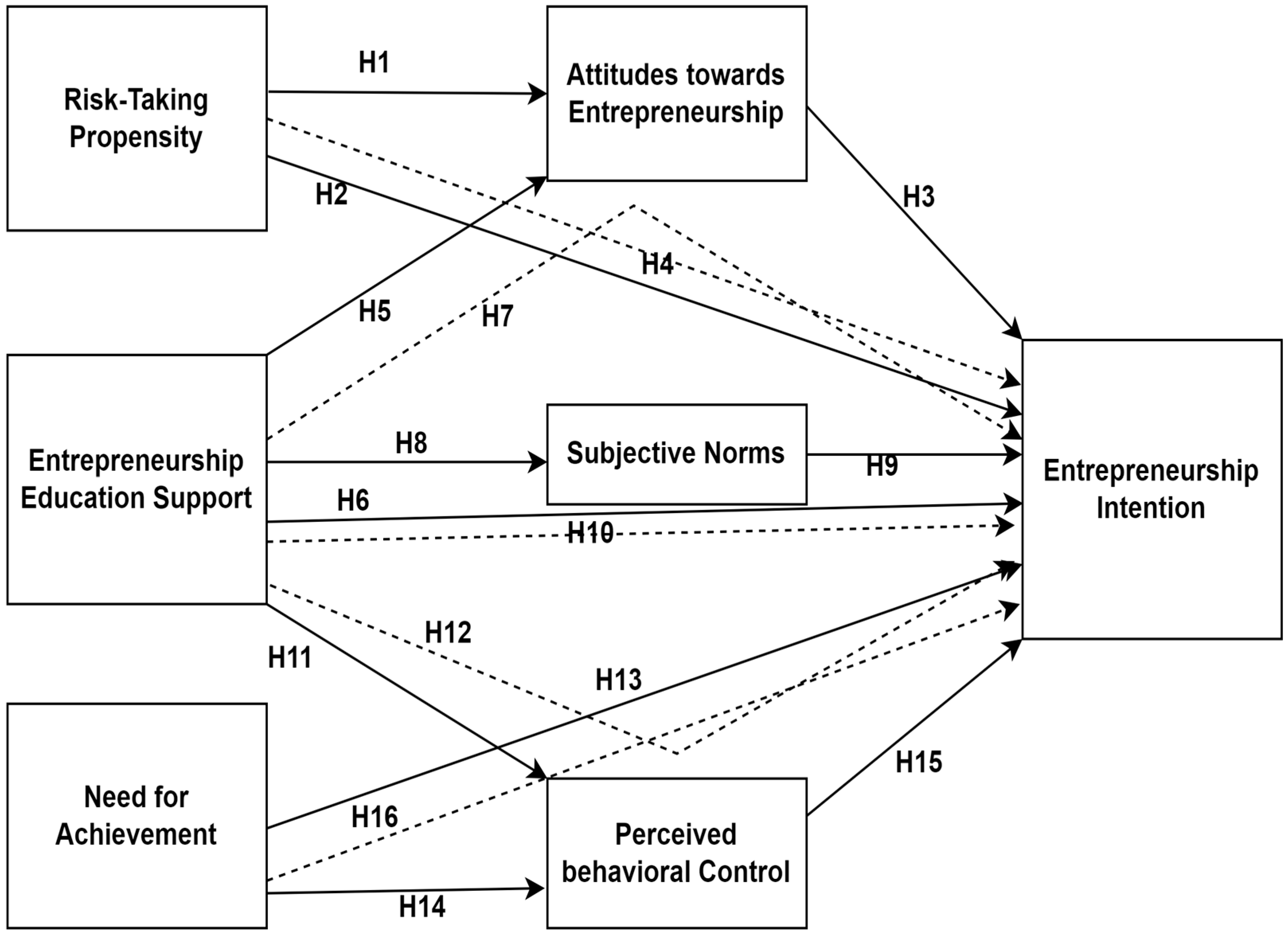

In the current study, the researchers investigated how a potential entrepreneur’s cognitive condition is influenced by risk-taking propensity (RTP), entrepreneurship education support (EES), and need for achievement (NFA) in relation to the intention to start a new business venture. Moreover, the researchers also investigated the mediating effect of attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control in the link between risk-taking propensity (RTP), entrepreneurship education support (EES), need for achievement (NFA), and entrepreneurship intention (EI). This study has three exploratory objectives: (1) to examine the relationship between the TPB and entrepreneurial intention from the perspective of university students in Bangladesh; (2) to demonstrate a modified model of the TPB, whether risk-taking propensities, entrepreneurial education support, and need for achievement are related to entrepreneurial intention; and (3) to provide evidence that the TPB is a useful construct for understanding the relationship of university students’ entrepreneurial intention (EI). With these broad goals in mind, researchers were able to examine the entrepreneurial mindset of university students of Bangladesh from personality traits (risk-taking propensity, need for achievement), entrepreneurship education support, and TPB perspective. This research aims to investigate these major questions.

RQ1. Is student EI influenced by RTP, EES, NFA, ATE, SN, and PBC?

RQ2. What roles do ATE, SN, and PBC play as mediators between students’ intentions to start their own business and the factors that influence RTP, EES, and NFA?

The study used the Partial Least Square Structural Equation Model (PLS-SEM) to test the proposed hypothesis. There are three major contributions to this research. First, this research expands upon the existing literature on EI, TPB, EES, and personality traits. Previous research has not specifically addressed personality traits, EES, TPB, and EI but has instead examined entrepreneurial intention in various settings (

Liñán and Chen 2009;

Munir et al. 2019;

Ng et al. 2021). However, this research shows that all TPB dimensions (except SN) have positive impacts on the EI of Bangladeshi university students. Second, we investigated the impact of three antecedents (risk-taking propensity, entrepreneurship education support, and need for achievement) on TPB dimensions and EI in Bangladeshi students, in contrast to previous studies that tended to focus on TPB and entrepreneurial intention (

Hossain et al. 2023,

2019;

Karmoker et al. 2020;

Rahaman et al. 2020a;

Rahman et al. 2022;

Ramadani et al. 2022;

Uddin et al. 2022;

Uddin and Bose 2012). Through this lens, we can emphasize how risk-taking propensity, entrepreneurship education support, and need for achievement can all contribute to explaining and shaping TPB dimensions, which in turn encourages entrepreneurship intention in Bangladeshi university students. Third, this research suggests a revised conceptual model for EI that incorporates the TPB dimensions and three additional variables as predictors. The findings can provide valuable insights to policymakers and universities that are committed to an entrepreneurial culture with useful strategies and directions. Researchers might start by looking into this question to find out what motivates and inspires young individuals to become entrepreneurs.

The layout of the article goes as follows: the literature review, hypotheses, and conceptual model are all shown in

Section 1. The sample, the method, and the data collection are all explained in

Section 2. The results can be found in

Section 3.

Section 4 focuses on the discussion, while

Section 5 presents limitations, future research avenues, and theoretical and managerial implications of the current study.

5. Discussion

In the current study, the researchers investigated how a student’s entrepreneurial cognitive condition is influenced by risk-taking propensity (RTP), entrepreneurship education support (EES), and need for achievement (NFA) in relation to the intention to start a new business venture in Bangladesh. Moreover, the researchers also investigated the mediating effect of the theory of planned behavior (TPB) in the link between risk-taking propensity (RTP), entrepreneurship education support (EES), need for achievement (NFA), and entrepreneurship intention (EI). Participants in the research were undergraduate and graduate students enrolled in public and private universities in Bangladesh. Following a discussion of the study’s contributions, the results indicate that TPB components (except subjective norms) and risk-taking propensity have a significant direct impact on the EI of the students in Bangladesh.

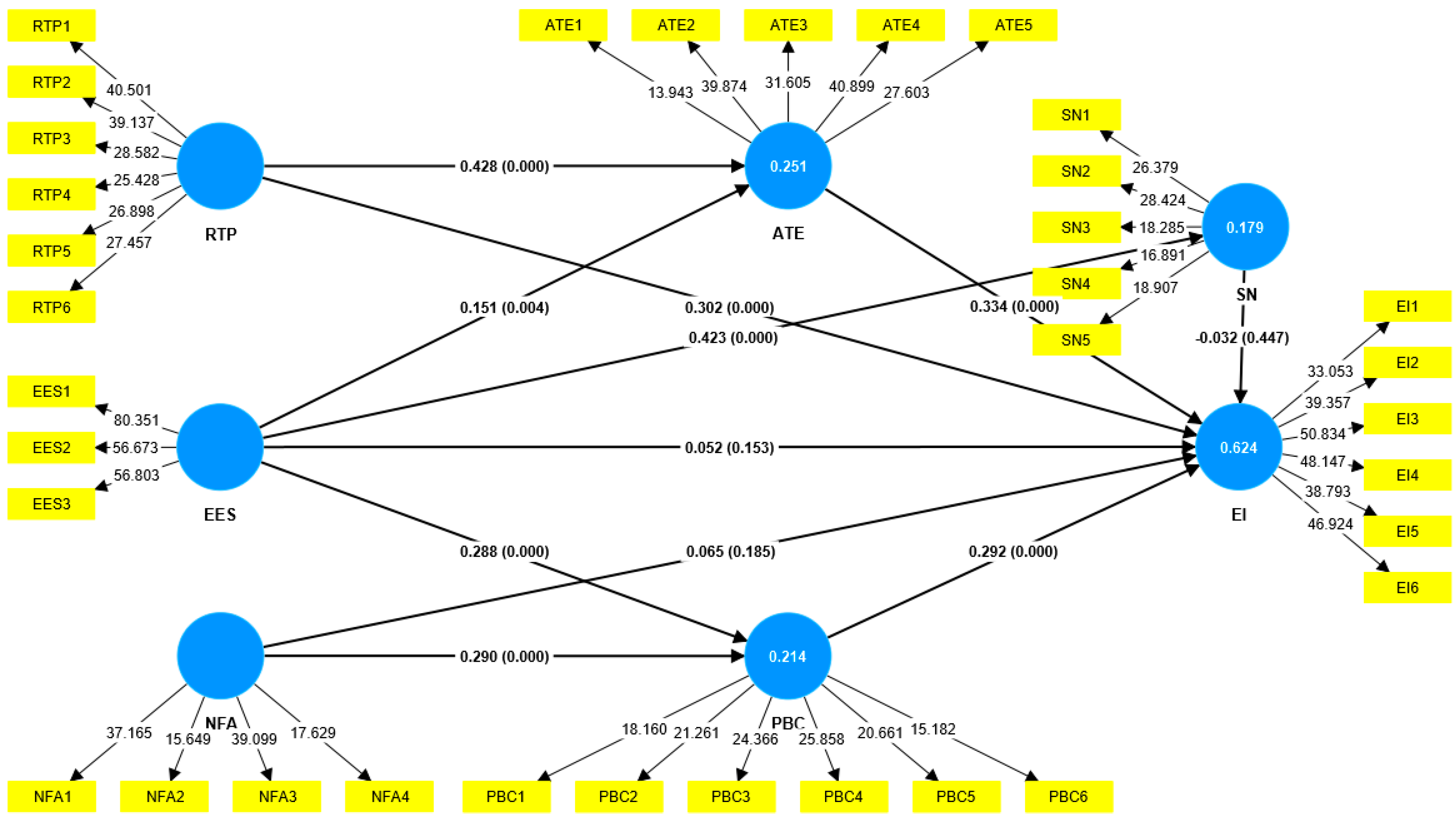

The main goal of this study was to find out if there was a direct link between RTP on ATE and EI. The results of the study show that there is a direct link between RTP on ATE and EI. Nevertheless, RTP had a more significant favorable effect on ATE (β = 0.292) than EI (β = 0.186). Our finding is supported by several previous studies (

Hossain et al. 2019;

Uddin and Bose 2012). It is clear that the individual who has a high risk-taking propensity has a more positive attitude toward entrepreneurship (

Ahmed et al. 2021). Importantly, ATE mediates the connection between RTP and EI, which is an indirect interaction between RTP and EI. Therefore, students’ risk-taking intentions increase their favorable attitudes toward entrepreneurship, which in turn boosts their intention to establish their own venture in Bangladesh. Previous research that suggests ATE moderated the relationship between RTP and EI is consistent with our results (

Farrukh et al. 2018;

Munir et al. 2019).

The subsequent objective of this research endeavor was to ascertain whether EES has a direct effect on EI, ATE, SN, and PBC. The study’s findings point to a direct link of EES with ATE, SN, and PBC. The effect of EES on SN (β = 0.423) was much stronger than those of ATE (β = 0.302) and PBC (β = 0.288). This result fits with what Yousaf et al. found in their study (

Qudsia Yousaf et al. 2022). The basic reasoning is that EES provides students with the skills and knowledge they need to focus on their career paths, cultivate positive attitudes and spirits toward starting new ventures, and acquire the necessary skills and abilities (

Kaur and Chawla 2023;

Nicolás et al. 2018). Moreover, people are more inclined to attribute positive social impacts and encouragement to their surroundings when it comes to entrepreneurial activity if they receive significant support for entrepreneurship education (

Nguyen et al. 2022). Entrepreneurship education has a crucial effect on individuals’ perceived behavioral control, which eventually boosts their entrepreneurial intention (

Porfírio et al. 2023). Nevertheless, this study’s findings suggest that EES does not have a direct effect on students’ entrepreneurship intention. Our finding is supported by previous studies (

Maheshwari and Kha 2022). On the other hand, our results do not agree with the results reported by

Hossain et al. (

2019) and Kanur Chawla et al. 2023. ATE and PBC fully mediate the link between EES and EI. It can be argued that EES has an indirect impact on EI by enhancing an individual’s attitude toward entrepreneurship (ATE) and perceived behavioral control (PBC). Previous findings are also consistent with our findings (

Nguyen et al. 2022). However, the relationship between EES and EI cannot be mediated via SN. It shows that university students in Bangladesh are not influenced by their social circles when deciding to start their own businesses. This trend could be a result of young people being more encouraged to follow their own passions and follow their dreams in the workplace, which is contributing to a more individualistic family dynamic.

Looking for a direct association between NFA, EI, and PBC was another goal of this research. In this study, researchers found that NFA and PBC are directly related. Similar results have been found in other studies (

Karimi et al. 2017;

Volery et al. 2013), which suggest that individuals with a strong desire to succeed frequently have high levels of self-efficacy and confidence. This confidence strengthens their perceived behavioral control because they believe they have the abilities and resources to achieve their goals, increasing their overall sense of control. The researchers did not find any direct relationship between NFA and EI. The probable reason may be that high-achieving individuals may actively seek and respond to feedback. Here, perceived behavioral control may be the feedback loop in which ambitious people evaluate and alter their entrepreneurial intentions based on feedback. Our finding is inconsistent with research conducted in Nigeria, Ghana, Morocco, and India that found a positive relationship between need for achievement and entrepreneurship intention (

Bouarir et al. 2023;

Mahajan and Gupta 2018;

Nunfam et al. 2022;

Palladan and Ahmad 2021). However, if PBC acts as a full mediator, the connection between NFA and EI becomes significantly stronger. Our finding is similar to a study conducted in Turkey and Poland that found that the relationship between need for achievement and entrepreneurship intention is mediated by perceived behavioral control (

Bağış et al. 2023b). It may be that high-achieving people are self-confident. Since they believe they have the skills and resources to achieve their goals, this confidence boosts their perceived behavioral control and ultimately increases their entrepreneurial intention.

At last, the researchers examined the impact of ATE, SN, and PBC on EI. The findings point to a positive association between ATE and EI. Our result is also supported by previous studies that suggest that ATE consistently boosts EI (

Anjum et al. 2021;

Ellahi et al. 2021). In addition, PBC significantly improves EI. Our finding is similar to the previous research findings (

Contreras-Barraza et al. 2022;

Doanh 2021;

Ellahi et al. 2021;

Vasileiou et al. 2023). Researchers were surprised to find no significant effect between SN and EI. However, our findings are consistent with studies that failed to find a relationship between SN and EI (

Alzamel 2021;

Azim and Islam 2022;

Ng et al. 2021). This trend might be due to the increasing degree of individualism in modern families, as young people are increasingly driven to pursue their own interests and desires in their careers.

6. Contribution, Limitations, and Future Research

6.1. Theoretical Contribution

Insights from this study have broad significance for a range of stakeholders, such as educators, policy makers, and those working to shape the entrepreneurial ecosystem specifically for emerging countries. Moreover, this study’s results provide important information for designing interventions and programs to help university students in Bangladesh become more entrepreneurial. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in Bangladesh to look at the mediation effect of the TBP construct on the relationship between risk-taking propensity, entrepreneurial education support, and the need for achievement on EI. The findings of our empirical study show that in Bangladesh, ATE and PBC are crucial intermediaries between RTP, EES, and NFA in shaping students’ entrepreneurial intentions. This study concludes that university-based entrepreneurial education has the potential to significantly impact the next generation’s entrepreneurial endeavors by fostering the development of students’ positive attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived control behaviors. On the other hand, students’ entrepreneurial intentions can be better understood by looking at their personality features. Moreover, attitudes and intentions toward entrepreneurship are positively impacted by a risk-taking tendency characteristic.

Although the idea of entrepreneurship is well known, most of the research on the topic has focused on developed nations with well-established entrepreneurial ecosystems. Academics and practitioners in a rapidly developing economy can benefit from this study since it aims to cover a knowledge gap in the field of entrepreneurship intention, entrepreneurship education, personality variables, and the TPB context. A few studies have demonstrated that entrepreneurship education positively affects students’ intentions to start their own businesses (

Karmoker et al. 2020;

Mensah et al. 2021;

Porfírio et al. 2022;

Rahaman et al. 2020b;

Ramos et al. 2020), but only a small number of studies have examined the indirect relationship between EES and EI (

Entrialgo and Iglesias 2016;

Kaur and Chawla 2023;

Li et al. 2023;

Maheshwari and Kha 2022;

Nguyen et al. 2022;

Shah et al. 2020;

Uddin et al. 2022). Moreover, there has been no research conducted to investigate the impact of EES, RTP, or NFA on EI, particularly in the context of emerging countries. Thus, this study adds to the current body of knowledge by providing empirical evidence of the three antecedents of TPB in the setting of Bangladesh that mediate the indirect relationship between entrepreneurial educational support, risk-taking propensity, need for achievement, and entrepreneurial intention.

6.2. Practical Implications

The study findings have several practical implications for educational institutions, policymakers, and the government. A positive relationship exists between entrepreneurial education and attitudes toward entrepreneurship, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Therefore, the curriculum needs to be more business-oriented and practical in higher education programs. One way for universities to boost their students’ entrepreneurial spirit is by providing them with entrepreneurial education courses. However, universities should develop entrepreneurship education curriculums that are tailored to the cultural attributes of different countries, considering their specific settings and the requirements of their industries. To help students gain a more practical and relevant understanding of entrepreneurship, it could be helpful to incorporate real-world initiatives, mentorship opportunities, and practical experiences into the curriculum. Moreover, universities should provide students with hands-on experience in business startup and management to inspire them to pursue entrepreneurship as a career path. Students have a better chance of becoming entrepreneurs as they gain expertise in business and how to start their own companies (

Shi et al. 2019). It is important to note that students’ personal attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control are impacted by entrepreneurial education support. If universities organize business pitch competitions and other activities that apply what students learn to real-world situations, it will inspire students to become entrepreneurs and improve their attitudes toward entrepreneurship. That is why it is important for students to have the opportunity to work on research or spin-off initiatives while attending university. It is emphasized by

Liao et al. (

2022) that an entrepreneurial mindset is shaped through entrepreneurial education, and it is a key factor in motivating entrepreneurial intention. Universities should, therefore, provide students with the opportunities to launch their own businesses through business centers and incubators. Moreover, higher education institutions must work with industry to influence young people’s entrepreneurial intents and help them improve their skills and expertise. It is possible to enhance subjective norms by fostering a favorable perception of the function of entrepreneurship among all individuals. It is also important for policymakers to acknowledge that entrepreneurship is a key driver of economic growth and development. They should work to cultivate positive attitudes toward entrepreneurship, which can help spread knowledge about entrepreneurial orientation in a comprehensive way and create a thriving ecosystem for entrepreneurship. The study’s results can help policymakers measure and foster an entrepreneurial ecosystem that is more conducive to success.

6.3. Conclusion, Limitations, and Future Research

Economic growth and development are largely determined by a country’s entrepreneurial activities. Simply said, entrepreneurship has the potential to improve a nation’s economy by increasing employment opportunities. The aim of the study was to investigate how entrepreneurship education and personality traits have created an effect on the entrepreneurship intention of university students in Bangladesh and how the theory of planned behavior (TPB) mediates in this relationship. Results indicate that TPB components (except subjective norms) and risk-taking propensity have a significant direct impact on the EI of the students of Bangladesh.

Universities should be more focused on entrepreneurship education for the students. At the same time, universities should include modern entrepreneurship education learning in their curriculum that can boost the student’s entrepreneurship intention by creating a positive attitude toward entrepreneurship. Graduates who participate in entrepreneurial education programs have a better chance of becoming employers rather than employees, which would be an enormous boost to the nation’s long-term economic and social growth. Additionally, by teaching young people to be entrepreneurs, society can turn educated people from a social liability into a social asset that can make significant contributions to achieving inclusive and sustainable development goals. The government should support the universities to provide adequate funds for the proper implementation of the EE program.

In addition, our study sheds light on the specific educational, cultural, and social circumstances of Bangladesh, laying the groundwork for more precise interventions and policies. University students have the power to change the world, so it is critical that they should be part of an entrepreneurial ecosystem that encourages innovation, risk taking, and the integration of valuable entrepreneurship education. Our research has broad ramifications, and it is clear that entrepreneurship education programs trying to inspire university students to start their own businesses need to take all of these factors into account. Addressing risk perceptions, improving entrepreneurship education programs, and tapping into the natural desire for success can all help to create a more suitable atmosphere for the development of entrepreneurial aspirations. Moving forward, stakeholders, legislators, and educators should work together to develop and implement policies that will empower and inspire the next generation of entrepreneurs. This will facilitate the development of a more dynamic and robust entrepreneurial ecosystem. The findings of this study pave the way for more in-depth investigations and concrete programs to help universities unleash the entrepreneurial spirit of their students.

In addition to the contribution, this study raised several issues that need to be addressed in future studies. Two personality traits (risk-taking propensity and need for achievement) and entrepreneurial education support have been the exclusive focus of this study. However, other elements such as proactive personality, perceived creativity, moral obligation, and the environment of doing business may also influence students’ entrepreneurship intention. To further explore the relationship between these factors, it is recommended to employ a mixed-method or longitudinal strategy, as this study was quantitative in nature. Moreover, future research should focus on students from higher secondary levels to measure their entrepreneurship intention. Furthermore, future research can employ a multi-group analysis to compare students with and without work or entrepreneurial experience.