A Strategic Roadmap for the Wine Sector in the Setúbal Peninsula

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The COVID-19 Pandemic’s Impact on the Wine Industry and Consumer Behavior

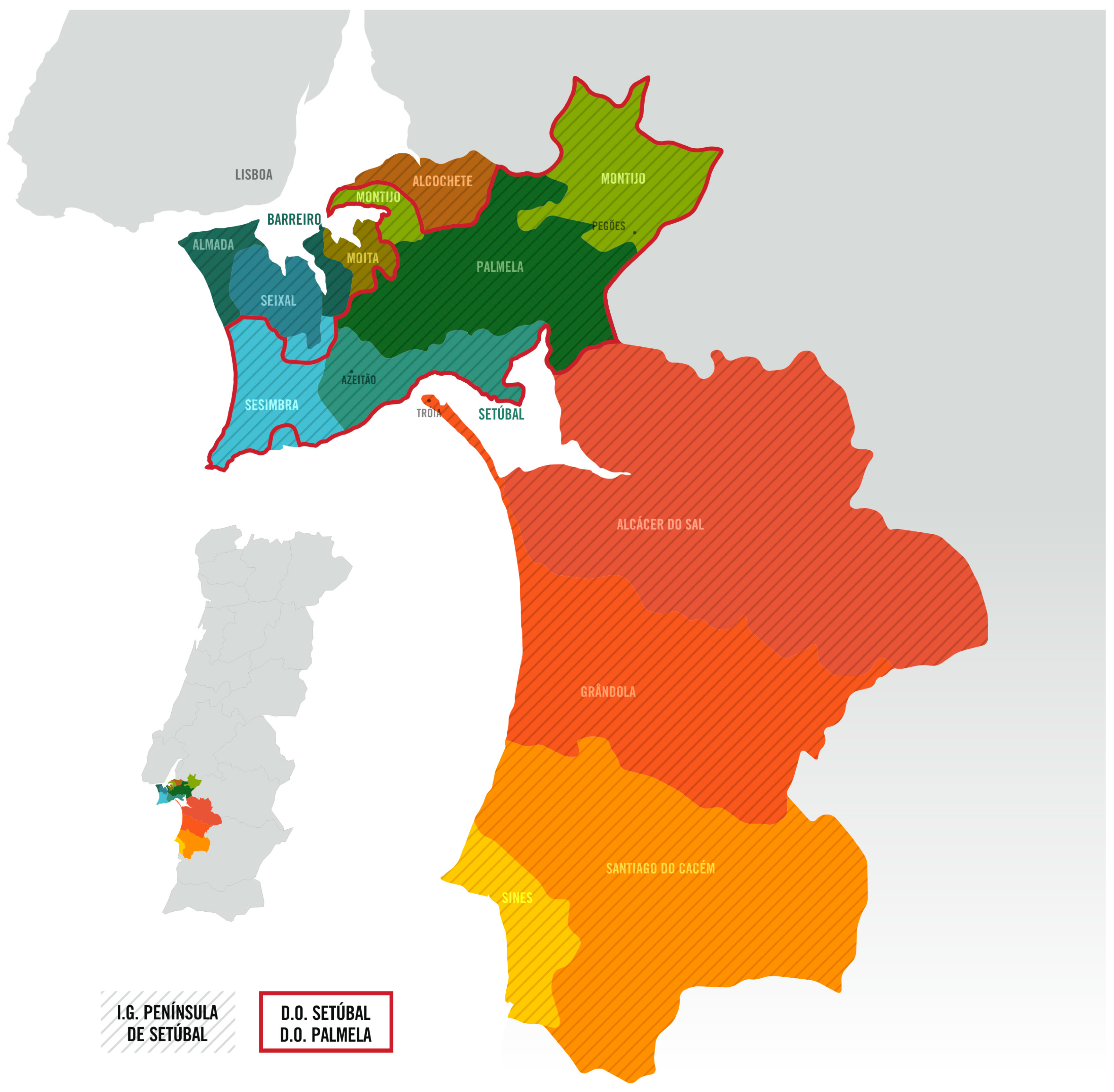

1.2. Setúbal Peninsula Wine Region

2. Methodology

- -

- How companies responded in terms of business models to recent challenges, particularly those stemming from the pandemic situation;

- -

- Identification of business-critical success factors;

- -

- Analysis of the main characteristics and resources of Portuguese competitors;

- -

- Identification of priority products and markets for Portuguese competitors;

- -

- Exploration of competitive advantages for development, considering the resources and characteristics of Portuguese competitors.

3. Strategic Roadmap for the Wine Sector in Setúbal Peninsula

3.1. Generic Competitiveness Conditions and Critical Success Factors

- -

- The greatest possible control or decrease in dependence on upstream activities (suppliers of raw materials and energy);

- -

- Use of less energy-consuming equipment;

- -

- Use of environmental control systems to adapt to environmental restrictions;

- -

- Product development (current or new), if a strategy of product extension is adopted (extending to possible entry into the most sophisticated international markets and the new segments associated with innovative products);

- -

- Reinforcing product quality and certification, which implies equipping the company with the necessary technical and technological competence (human resources and equipment);

- -

- Use of direct commercialization channels with adequate capacity for communication, customer service, response and technical assistance, which are associated with efficient logistics procedures encompassing the offer of different producers, increase the scale of operations and reduce transportation costs per traded bottle.

- -

- Price: This is crucial, especially for higher volume and less sophisticated products and in markets with lower added value;

- -

- Image: Company and product visibility and notoriety can condition consumer choice due to greater brand recognition and possible national and international awards;

- -

- Quality: The most sophisticated markets want unique wines with unique characteristics. The remaining segments seek wines, which optimize the relationship between price and perceived quality;

- -

- Response capacity: In international markets and distribution, the scale of operations is essential, since it is important to respond not only in terms of quality but also in terms of quantity to cope with the higher volume of operations;

- -

- Relationship: The ability to respond to the evolution in market needs through a constant adaptation of supply to demand is also a factor highly valued by international markets and more sophisticated customer segments.

- -

- Process efficiency: To reduce the pressure on prices, companies seek to reduce their logistics costs and increase vineyard productivity through new processes in order to increase the scale of their production with the same resources;

- -

- Marketing communication: Attending international events to promote Portuguese wines to the final customers, obtaining awards and developing an attractive product image associated with its uniqueness and the characteristics of the markets are essential to give visibility and notoriety to Portuguese wines;

- -

- Technological innovation: Acquiring more advanced equipment and technology has enabled the consolidation of working procedures and contributed to greater activity, productivity and greater responsiveness, both in terms of the scale of operation and in terms of deadlines;

- -

- Product innovation: The sector’s traditional and unique practices, along with the diversity of grape varieties in the national territory, contribute to constant innovation of the wines produced and to providing access to more sophisticated markets, which are less sensitive to price through a relevant degree of differentiation compared to the main international competitors;

- -

- Market adequacy: Building sustainable partnership relations with the destination markets contributes to establishing trustful relationships and a better knowledge of the clients’ needs, increasing the cost of switching to possible alternative suppliers.

3.2. Critical Competitiveness Areas

- -

- The systematic search for better suppliers in terms of price and quality, possibly raising the opportunity to create central purchases to increase the negotiating power with the main material suppliers (such as glass, cardboard, labeling, etc.);

- -

- Use of less energy-consuming equipment;

- -

- Adequacy of installed capacity for the expected production volumes, avoiding, as much as possible, surpluses or under-capacity situations;

- -

- Establishing partnerships and business associations in order to reduce the costs of raw material acquisition and distribution of the final products in the destination markets;

- -

- Good planning, which allows the maximum use of existing resources (facilities, equipment and workforce), avoiding inactivity;

- -

- Correct placement of the installations and equipment in order to avoid unnecessary transportation of materials and components;

- -

- Good stock management (raw materials, components, work in progress and finished products) to avoid excesses (fixed assets costing money) or production disruptions due to lack of material.

- -

- Good planning and programming of the productive activity, which will contribute not only to better use of the resources but also to meeting deadlines and, through monitoring and control actions, to making possible adjustments;

- -

- Flexible production processes, which allow—at reduced costs—production changes and/or changes in production volumes.

- -

- The creation of unique wines through the use of traditional production techniques, the properties of national grape varieties, and the climatic and natural conditions of the territory;

- -

- Quality procedures (control, prevention, inspection, etc.), which enable obtaining improved quality standards and, essentially, a reduction in costs due to non-conformities;

- -

- Equipment and technological processes adjusted to the type of production, which avoid deficiencies and consequently lower the costs of waste and/or corrections;

- -

- Suitable product design for the characteristics of its use;

- -

- The use of materials and components of adequate quality to avoid deficiencies in the manufactured products.

- -

- Development of marketing tools in the various languages of the main export markets, which enhance the image of the company and the products produced and are aligned with the company’s commercial strategy;

- -

- Establishment of wine clubs for top-quality products, contributing to institutional notoriety;

- -

- Website development to promote the company and its products to markets and international customers, which are not geographically close;

- -

- Participating in competitions for prizes, which value and highlight the quality of the wines;

- -

- Achieving increasingly better grades in specialized wine magazines (e.g., Wine Spectator, The Wine Advocate, Wine Enthusiast) and prizes in leading international wine competitions;

- -

- Participation in fairs and events promoted by sector associations in order to boost relationships with partners and business in international markets;

- -

- Promoting meetings and visits of potential business partners, contributing to the development of close and trust-based relationships;

- -

- Establishing communication channels, which allow constant monitoring of customer needs, fostering a relational marketing strategy with the creation of communities with consumers and customer relationship management (CRM) with the main customers.

- -

- An adequate marketing and distribution structure close to the customers;

- -

- A technical staff conveniently prepared for the detection and solution of customer problems;

- -

- The ability to create a product range suited to customers’ changing needs over time.

- -

- What internationalization opportunities might be seized most easily?

- -

- What lessons can we learn from the pandemic, and what are the main challenges and opportunities emerging and their impact on business models and internal resources?

- -

- Is innovation important in achieving competitive advantages in terms of products and processes?

- -

- Given the technological innovations resulting from the pandemic and the new emerging markets, will e-commerce have greater relevance in the business models of Portuguese companies?

- -

- How are companies addressing and planning for the long term to ensure the sustainability of the activity and the environment?

4. Possible Business Development Guidelines

4.1. Products and Markets

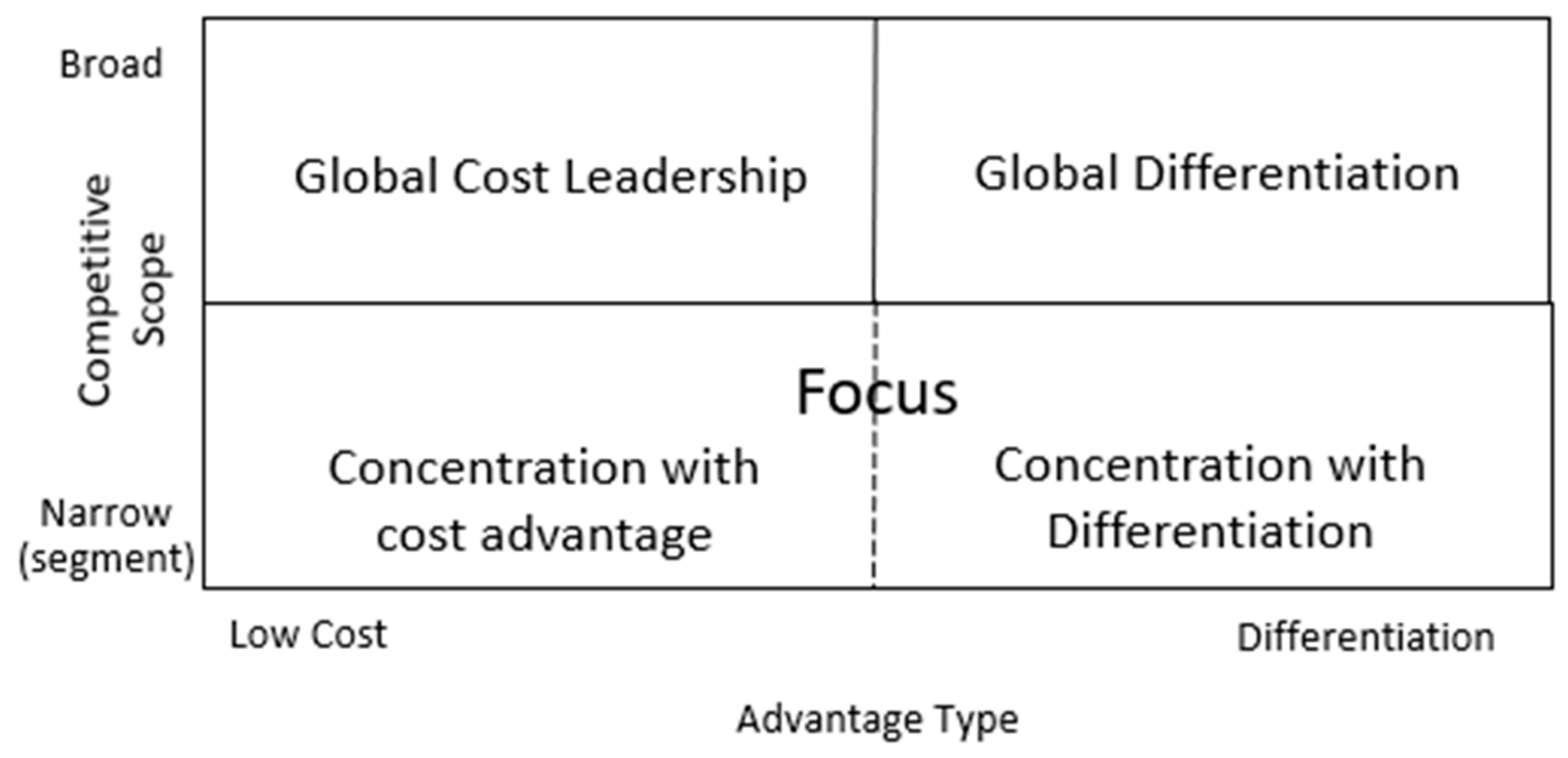

4.2. Types of Competitive Advantage

- Seek to achieve economies of scale and experience, which requires a greater effort to obtain market share;

- Have strict cost control in terms of suppliers, efficient use of equipment, employees and stocks;

- Strive for maximum product standardization;

- Implement process simplification.

- Possess and master the technologies, especially those associated with product development;

- Meet the delivery deadlines better than the competition;

- Make a permanent effort in promotion and publicity, aiming above all to create good notoriety and/or brand image.

5. Development of a Business Model

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aleffi, Chiara, Sabrina Tomasi, Concetta Ferrara, Cristina Santini, Gigliola Paviotti, Federica Baldoni, and Alessio Cavicchi. 2020. Universities and Wineries: Supporting Sustainable Development in Disadvantaged Rural Areas. Agriculture 10: 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, Sofia, Susana Mesquita, and Inês Carvalho. 2022. The COVID-19 impacts on the hospitality industry highlights from experts in portugal. Tourism and Hospitality Management 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansoff, H. Igor. 1984. Implanting Strategic Management. New York: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bibicioiu, Sorin, and Romeo Cătălin Creţu. 2013. Enotourism: A Niche Tendency within the Tourism Market. Scientific Papers Series Management, Economic Engineering in Agriculture and Rural Development 13. [Google Scholar]

- Bruwer, Johan, Michael Coode, Anthony Saliba, and Frikkie Herbst. 2013. Wine Tourism Experience Effects of the Tasting Room on Consumer Brand Loyalty. Tourism Analysis 18: 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmer, Adam, Natalia Velikova, Jean Hertzman, Christine Bergman, Michael Wray, and Taricia LaPrevotte Pippert. 2020. An Inquiry Into the Pedagogy of the Sensory Perception Tasting Component of Wine Courses in the Time of COVID-19. Wine Business Journal 4: 96–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroquino, Javier, Nieves Garcia-Casarejos, and Pilar Gargallo. 2020. Classification of Spanish Wineries According to Their Adoption of Measures against Climate Change. Journal of Cleaner Production 244: 118874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, Katherine L., and Roger L. Burritt. 2013. Critical Environmental Concerns in Wine Production: An Integrative Review. Journal of Cleaner Production 53: 232–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commité Européen des Enterprises Vins. 2021. EU Wine Sector-CEEV. Available online: https://www.ceev.eu/about-the-eu-wine-sector/ (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- Compés, Raúl, Samuel Faria, Tânia Gonçalves, João Rebelo, Vicente Pinilla, and Katrin Simon Elorz. 2022. The Shock of Lockdown on the Spending on Wine in the Iberian Market: The Effects of Procurement and Consumption Patterns. British Food Journal 124: 1622–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, Matthew. 2020. Three Sticks Wines: Digital Marketing, Branding, and Hospitality During a Crisis. Wine Business Journal 4: 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeYoung, Hannah. 2020. Napa Green: Funding Nonprofit Social Ventures in Crisis. Wine Business Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development. 2022. Agri-Wine Prices. Available online: https://agridata.ec.europa.eu/extensions/DashboardWine/WinePrice.html (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- Duarte Alonso, Abel, Alessandro Bressan, Oanh Thi Kim Vu, Lan Thi Ha Do, Roberta Garibaldi, and Andrea Pozzi. 2022. How Consumers Relate to Wine during COVID-19—A Comparative, Two Nation Study. International Journal of Wine Business Research 34: 590–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, Magalie, Lara Agnoli, Jean Marie Cardebat, Raúl Compés, Benoit Faye, Bernd Frick, Davide Gaeta, Eric Giraud-Héraud, Eric Le Fur, Livat Florine, and et al. 2021. Did Wine Consumption Change during the Covid-19 Lockdown in France, Italy, Spain, and Portugal? Journal of Wine Economics 16: 131–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastham, Jane. 2022. Post-Covid-19 Developments in the Wine Tourism Sector. In Routledge Handbook of Wine Tourism. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2022. Agri-Food Data Portal—Agricultural Markets. Available online: https://agridata.ec.europa.eu/extensions/DataPortal/wine.html (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- European Commission, DG Agriculture, and Rural Development. 2020. Short Term Outlook for EU Agricultural Markets in 2020: Spring 2020. Luxembourg: European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament and Council. 2013. Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 December 2013. Available online: https://eurlex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32013R1308 (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- Eurostat. 2021. Key Figures on the European Food Chain—2021 Edition. Statistical Books. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-key-figures/-/ks-fk-21-001 (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- Ferrer, Juan R., María Carmen García-Cortijo, Vicente Pinilla, and Juan Sebastián Castillo-Valero. 2022. The Business Model and Sustainability in the Spanish Wine Sector. Journal of Cleaner Production 330: 129810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, Shana Sabbado. 2018. What Is Sustainability in the Wine World? A Cross-Country Analysis of Wine Sustainability Frameworks. Journal of Cleaner Production 172: 2301–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortune Business Insights. n.d. Wine Market Size, Share, Analysis and Industry Trends. Available online: https://www.fortunebusinessinsights.com/wine-market-102836 (accessed on 19 January 2024).

- Fountain, Joanna, Rory Hill, and Nicholas Cradock-Henry. 2022. Wine Tourism and the Global Pandemic Realizing Opportunities for New Wine Markets and Experiences. In Routledge Handbook of Wine Tourism. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco Avillez. 2014. A Agricultura Portuguesa - Caminhos Para Um Crescimento Sustentaável. AGRO.GES. Available online: https://www.agroges.pt/a-agricultura-portuguesa-caminhos-para-um-crescimento-sustentavel/ (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- Freire, Adriano. 1998. Estratégia—Sucesso Em Portugal. Lisboa: Verbo. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes-Fernández, Rosana, Javier Martínez-Falcó, Eduardo Sánchez-García, and Bartolomé Marco-Lajara. 2022. Does Ecological Agriculture Moderate the Relationship between Wine Tourism and Economic Performance? A Structural Equation Analysis Applied to the Ribera Del Duero Wine Context. Agriculture 12: 2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, Donald, Ross Dowling, Jack Carlsen, and Donald Anderson. 1999. Critical Success Factors for Wine Tourism. International Journal of Wine Marketing 11: 20–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C. Michael, and Liz Sharples. 2008. Food and Wine Festivals and Events Around the World: Development, Management and Markets. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Mark W., Clayton M. Christensen, and Henning Kagermann. 2008. Reinventing Your Business Model. Harvard Business Review 86: 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Jorge, Oriol, Adria Pons, Josep Rius, Carla Vintró, Jordi Mateo, and Jordi Vilaplana. 2020. Increasing Online Shop Revenues with Web Scraping: A Case Study for the Wine Sector. British Food Journal 122: 3383–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kshetri, Nir. 2018. 1 Blockchain’s Roles in Meeting Key Supply Chain Management Objectives. International Journal of Information Management 39: 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y. 2020. Wine Report 2020, Statista Consumer Market Outlook-Segment Report. Available online: https://www.statista.com/study/48818/wine-report/ (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- Miftari, Iliriana, Marija Cerjak, Marina Tomić Maksan, Drini Imami, and Vlora Prenaj. 2021. Consumer Ethnocentrism and Preference for Domestic Wine in Times of Covid-19. Studies in Agricultural Economics 123: 103–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério da Agricultura, do Desenvolvimento Rural e das Pescas (MADRP). 2007. Olivicultura—Diagnóstico Sectorial. Lisbon: Gabinete de Planeamento e Políticas. [Google Scholar]

- Niklas, Britta, Jean Marie Cardebat, Robin M. Back, Davide Gaeta, Vicente Pinilla, João Rebelo, Roberto Jara-Rojas, and Guenter Schamel. 2022. Wine Industry Perceptions and Reactions to the COVID-19 Crisis in the Old and New Worlds: Do BusinessModels Make a Difference? Agribusiness 38: 810–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osterwalder, Alexander, and Yves Pigneur. 2010. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers. In A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, Michael Quinn. 2015. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 4th ed. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, Michael E. 1980. Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors. Boston: Faculty & Research, Harvard Business School. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, Michael E. 1985. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance. New York City: The Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Profi Press. n.d. The Pandemic Has Significantly Disrupted the Wine Market. Available online: https://zemedelec.cz/pandemievyrazne-narusila-trh-s-vinem/ (accessed on 19 January 2024).

- Rebelo, João, Raúl Compés, Samuel Faria, Tânia Gonçalves, Vicente Pinilla, and Katrin Simón-Elorz. 2021. Covid-19 Lockdown and Wine Consumption Frequency in Portugal and Spain. Spanish Journal of Agricultural Research 19: e0105R. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmenti, Emanuele, Giuseppina Migliore, Caterina Patrizia Di Franco, and Valeria Borsellino. 2016. Is There Sustainable Entrepreneurship in the Wine Industry? Exploring Sicilian Wineries Participating in the SOStain Program. Wine Economics and Policy 5: 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, David. n.d. Doing Qualitative Research: A Practical Handbook, 3rd ed. New York: Sage Publications.

- Stake, Robert E. 2010. Qualitative Research: Studying How Things Work. In Acta Universitatis Agriculturae et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis. New York City: The Guilford Press, p. 53. [Google Scholar]

- Statista Market Forecast. 2022. Wine—Worldwide. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/cmo/alcoholic-drinks/wine/worldwide (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- Teece, David J. 2010. Business Models, Business Strategy and Innovation. Long Range Planning 43: 172–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugaglia, Adeline Alonso. 2019. Introduction: The Diversity of Organizational Patterns in the Wine Industry. In The Palgrave Handbook of Wine Industry Economics. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikström, Kim, Karlos Artto, Jaakko Kujala, and Jonas Söderlund. 2010. Business Models in Project Business. International Journal of Project Management 28: 832–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittwer, Glyn, and Kym Anderson. 2021. Covid-19 and Global Beverage Markets: Implications for Wine. Journal of Wine Economics 16: 117–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Robert. 2011. Qualitative Research From Start To Finish. New York City: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Robert K. 2003. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 3rd ed. New York: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

| Legal Structure of the Business | Number of Employees | In Operation Since (Year) | Business Model (Nationally) | Business Model (Internationally) | Age of the Main Manager |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Private Limited Company | 30–49 | 1950 | Self-distribution | In-house export team | Between 41 and 65 years old |

| Private Limited Company | 5–9 | 2008 | Self-distribution | Both | Over 25 and under 41 years old |

| Private Limited Company | 15–29 | 1996 | Both | Both | Over 25 and under 41 years old |

| Limited Liability Cooperative | 76–100 | 1958 | Self-distribution | In-house export team | Between 41 and 65 years old |

| Private Limited Company | 10–14 | 2017 | Both | Both | Between 41 and 65 years old |

| Private Limited Company | 5–9 | 1992 | Using national distributors | Both | Between 41 and 65 years old |

| Cooperative | 50–75 | 1955 | Using national distributors | Both | Between 41 and 65 years old |

| Private Limited Company | 1–4 | 2011 | Both | In-house export team | Between 41 and 65 years old |

| Sole Proprietorship via Shares (LLC) | 5–9 | 1999 | Both | Both | Between 41 and 65 years old |

| Public Limited Company | 15–29 | 1964 | Both | Both | Between 41 and 65 years old |

| Private Limited Company | 10–14 | 2008 | Self-distribution | Both | Between 41 and 65 years old |

| Private Limited Company | 1–4 | 1997 | Both | Using trading companies | Agents or brokers |

| Key Buying Factors | Key Competition Factors | Critical Success Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Prices | Process Efficiency | Prices |

| Response Capacity | Technological Innovation | Process Innovation |

| Image | Marketing Communication | Marketing Communication |

| Quality | Product Innovation | Product Differentiation |

| Relationship | Market Adequacy | Service Level |

| Wine Type | National Market | International Market | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intra EU | Extra EU | |||||

| Restaurants | Distribution | Restaurants | Distribution | Restaurants | Distribution | |

| Certified | ||||||

| Non-Certified | ||||||

| January–March | Variation 1st Qtr. 21/22 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2021 | 2022 | ||

| Volume Quota | |||||||||

| Restaurants | 29% | 30% | 31% | 32% | 20% | 17% | 6% | 26% | 20% |

| Distribution | 71% | 70% | 69% | 68% | 80% | 83% | 94% | 74% | −20% |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 0% |

| Value Quota | |||||||||

| Restaurants | 54% | 56% | 55% | 56% | 39% | 34% | 13% | 48% | 35% |

| Distribution | 46% | 44% | 45% | 44% | 61% | 66% | 87% | 52% | −35% |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 0% |

| Region | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Certified wines (total) | 109,737,188 | 112,363,732 | 115,103,876 | 124,599,625 | 112,002,071 | 115,420,759 |

| Minho | 18,625,525 | 19,983,662 | 20,334,191 | 21,469,566 | 19,721,313 | 19,828,643 |

| Tras os montes | 539,211 | 687,664 | 429,621 | 392,807 | 274,448 | 283,167 |

| Douro | 11,753,648 | 13,623,943 | 13,143,932 | 12,900,583 | 12,304,512 | 13,632,325 |

| Beiras | 108,515 | 88,963 | 259,060 | 298,131 | 93,359 | 126,421 |

| Terras de cister | 33,870 | 27,242 | 23,820 | 29,584 | 54,417 | 31,020 |

| Beira atlantico | 1,062,653 | 762,668 | 1,066,136 | 883,932 | 522,329 | 376,644 |

| Terras do dão | 6,243,657 | 5,984,241 | 6,482,985 | 6,587,279 | 5,490,780 | 5,300,953 |

| Beira interior | 372,565 | 415,358 | 770,569 | 903,668 | 848,363 | 969,075 |

| Lisbon | 3,895,621 | 4,806,982 | 5,482,162 | 5,289,946 | 4,587,955 | 5,044,984 |

| Tejo | 4,845,416 | 5,201,550 | 5,167,240 | 10,234,310 | 8,944,478 | 8,605,083 |

| Setúbal peninsula | 14,042,265 | 14,810,295 | 17,624,800 | 20,081,558 | 20,605,445 | 21,792,324 |

| Alentejo | 47,928,070 | 45,576,684 | 43,835,850 | 45,113,270 | 38,329,383 | 39,213,524 |

| Algarve | 286,172 | 394,480 | 483,510 | 414,991 | 225,289 | 216,596 |

| Non-certified wines (total) | 147,163,289 | 155,031,652 | 148,990,336 | 153,690,291 | 138,726,043 | 133,221,786 |

| Imported | 3,046,159 | 3,186,089 | 4,597,781 | 8,165,902 | 8,380,755 | 9,317,916 |

| National | 144,117,130 | 151,845,563 | 144,392,555 | 145,524,389 | 130,345,288 | 123,903,870 |

| Wines sales (total) | 256,900,477 | 267,395,384 | 264,094,212 | 278,289,916 | 250,728,114 | 248,642,545 |

| Region/Distribution Channel | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | VAR% 2021/2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minho | 4.43 | 4.68 | 4.79 | 4.86 | 4.21 | 4.24 | −4.2% |

| Restaurants | 8.34 | 8.39 | 8.77 | 8.86 | 8.71 | 8.71 | 4.4% |

| Distribution | 3.11 | 3.18 | 3.27 | 3.29 | 3.27 | 3.33 | 7.1% |

| Douro | 7.13 | 7.73 | 8.49 | 9.61 | 8.26 | 8.23 | 15.5% |

| Restaurants | 13.14 | 14.01 | 15.71 | 16.52 | 16.82 | 16.09 | 22.4% |

| Distribution | 4.61 | 4.76 | 5.22 | 5.88 | 5.93 | 6.19 | 34.4% |

| Terras do dão | 5.40 | 5.18 | 4.76 | 4.95 | 4.47 | 4.49 | −16.7% |

| Restaurants | 8.55 | 10.99 | 8.41 | 8.14 | 7.90 | 7.68 | −10.1% |

| Distribution | 3.09 | 3.06 | 3.16 | 3.35 | 3.52 | 3.72 | 20.2% |

| Lisbon | 4.29 | 4.33 | 4.59 | 4.44 | 3.94 | 4.51 | 5.1% |

| Restaurants | 8.62 | 9.23 | 10.04 | 9.73 | 11.96 | 11.14 | 29.4% |

| Distribution | 2.97 | 3.09 | 3.34 | 3.39 | 3.41 | 3.53 | 18.8% |

| Tejo | 3.76 | 3.77 | 3.75 | 3.23 | 3.08 | 3.11 | −17.1% |

| Restaurants | 6.51 | 6.19 | 5.86 | 4.65 | 5.05 | 5.21 | −20.0% |

| Distribution | 2.59 | 2.66 | 2.84 | 2.40 | 2.46 | 2.53 | −2.4% |

| Setúbal peninsula | 3.50 | 3.62 | 3.66 | 3.81 | 3.44 | 3.58 | 2.3% |

| Restaurants | 9.46 | 9.83 | 9.87 | 9.56 | 8.99 | 9.56 | 1.1% |

| Distribution | 2.71 | 2.86 | 2.99 | 3.00 | 3.03 | 3.20 | 18.4% |

| Alentejo | 4.72 | 5.27 | 5.85 | 6.02 | 5.22 | 5.30 | 12.3% |

| Restaurants | 10.44 | 10.89 | 11.56 | 11.39 | 11.55 | 11.89 | 14.0% |

| Distribution | 3.22 | 3.53 | 3.79 | 3.96 | 4.04 | 4.23 | 31.4% |

| Total | 4.76 | 5.14 | 5.42 | 5.49 | 4.80 | 4.93 | 3.6% |

| Restaurants | 9.85 | 10.41 | 10.81 | 10.40 | 10.47 | 10.65 | 8.2% |

| Distribution | 3.21 | 3.42 | 3.59 | 3.66 | 3.73 | 3.92 | 22.0% |

| Intra + Extra EU | HL | Variation 2021/2020 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January–December | ||||||||

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | ||

| Certified Wine | 928,490 | 981,167 | 1,105,731 | 1,118,730 | 1,155,086 | 1,351,796 | 1,429,605 | 5.8% |

| Wine with Denomination of Origin (DO) | 517,656 | 550,863 | 596,491 | 618,225 | 606,058 | 688,890 | 712,533 | 3.4% |

| Wine with Geographical Identification (IG) | 410,834 | 430,304 | 509,241 | 500,505 | 549,028 | 662,906 | 717,072 | 8.2% |

| Wine (ex-table) | 1,128,260 | 1,070,522 | 1,154,685 | 1,138,946 | 1,102,411 | 1,089,173 | 1,107,916 | 1.7% |

| Wine | 1,085,056 | 1,031,731 | 1,121,370 | 1,067,887 | 1,044,513 | 1,028,243 | 1,054,210 | 2.5% |

| Wine with Grape Variety Indication | 43,203 | 38,792 | 33,315 | 71,059 | 57,898 | 60,931 | 53,707 | −11.9% |

| Liqueur Wine with Protected Denomination of Origin (DOP)/Protected Geographical Identification (IGP) | 701,527 | 678,884 | 677,690 | 646,923 | 657,908 | 657,029 | 691,440 | 5.2% |

| Porto | 671,981 | 651,340 | 640,027 | 607,327 | 617,049 | 611,902 | 652,120 | 6.6% |

| Madeira | 24,294 | 21,521 | 28,246 | 28,135 | 27,052 | 23,827 | 25,885 | 8.6% |

| Others | 5252 | 6023 | 9417 | 11,461 | 13,807 | 21,300 | 13,434 | −36.9% |

| Liqueur Wine without DOP/IGP | 8583 | 9487 | 3120 | 3471 | 3011 | 2603 | 3921 | 50.7% |

| Sparkling Wines | 13,205 | 17,557 | 13,948 | 22,361 | 17,577 | 20,965 | 18,199 | −13.2% |

| Other Wines and Musts | 18,123 | 21,889 | 26,395 | 27,768 | 27,217 | 29,819 | 35,222 | 18.1% |

| Total | 2,798,189 | 2,779,505 | 2,981,569 | 2,958,198 | 2,963,210 | 3,151,384 | 3,286,303 | 4.3% |

| Total Intra EU | 1,402,522 | 1,646,785 | 1,678,630 | 1,687,863 | 1,567,970 | 1,411,747 | 1,506,129 | 6.7% |

| Total Extra EU | 1,395,667 | 1,132,719 | 1,302,940 | 1,270,335 | 1,395,240 | 1,739,637 | 1,780,173 | 2.3% |

| Destination | HL | Variation 2021/2020 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January–December | ||||||||

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | ||

| Africa | 744,080 | 383,543 | 468,250 | 425,928 | 495,335 | 447,609 | 456,921 | 2.1% |

| America | 378,452 | 419,664 | 497,364 | 525,433 | 572,320 | 660,942 | 690,730 | 4.5% |

| Asia | 122,023 | 130,183 | 161,784 | 135,504 | 124,429 | 94,860 | 112,960 | 19.1% |

| European community | 1,402,522 | 1,646,785 | 1,678,630 | 1,687,863 | 1,567,970 | 1,411,747 | 1,506,129 | 6.7% |

| Non-community Europe | 139,362 | 184,952 | 159,232 | 165,944 | 182,494 | 516,242 | 502,602 | −2.6% |

| Oceania | 8759 | 10,928 | 11,873 | 13,726 | 16,706 | 18,701 | 15,096 | −19.3% |

| Other destinations | 2991 | 3450 | 4435 | 3800 | 3956 | 1283 | 1864 | 45.4% |

| Total | 2,798,189 | 2,779,505 | 2,981,569 | 2,958,198 | 2,963,210 | 3,151,384 | 3,286,303 | 4.3% |

| Block/Macro Area | Component | Synthetic Description |

|---|---|---|

| Offer (What?) | Value Proposition (VP) | Describes the set of products and services, which create value for a specific customer segment. |

| Client (Who?) | Customer Segments (CS) | Various groups of people or organizations, which a company aims to reach. |

| Channels (CN) | Describes how a company communicates and tries to influence its customer segments to deliver a value proposition. | |

| Customer Relationship (RC) | Describes the types of relationships a company establishes with specific customer segments. | |

| Infrastructure (How?) | Key Resources (KR) | Describes the most important assets for the functioning of the business model. |

| Key Activities (KA) | Describes the most important things a company must do to make its business model work. | |

| Key Partnerships (KP) | Describes the network of suppliers and partners, which make the business model work. | |

| Financial Viability (How much?) | Cost Structure (CS) | Describes all the resources involved in operating a business model, as well as their cost. |

| Income Flow (IF) | Represents the money, which a company generates from each customer segment. |

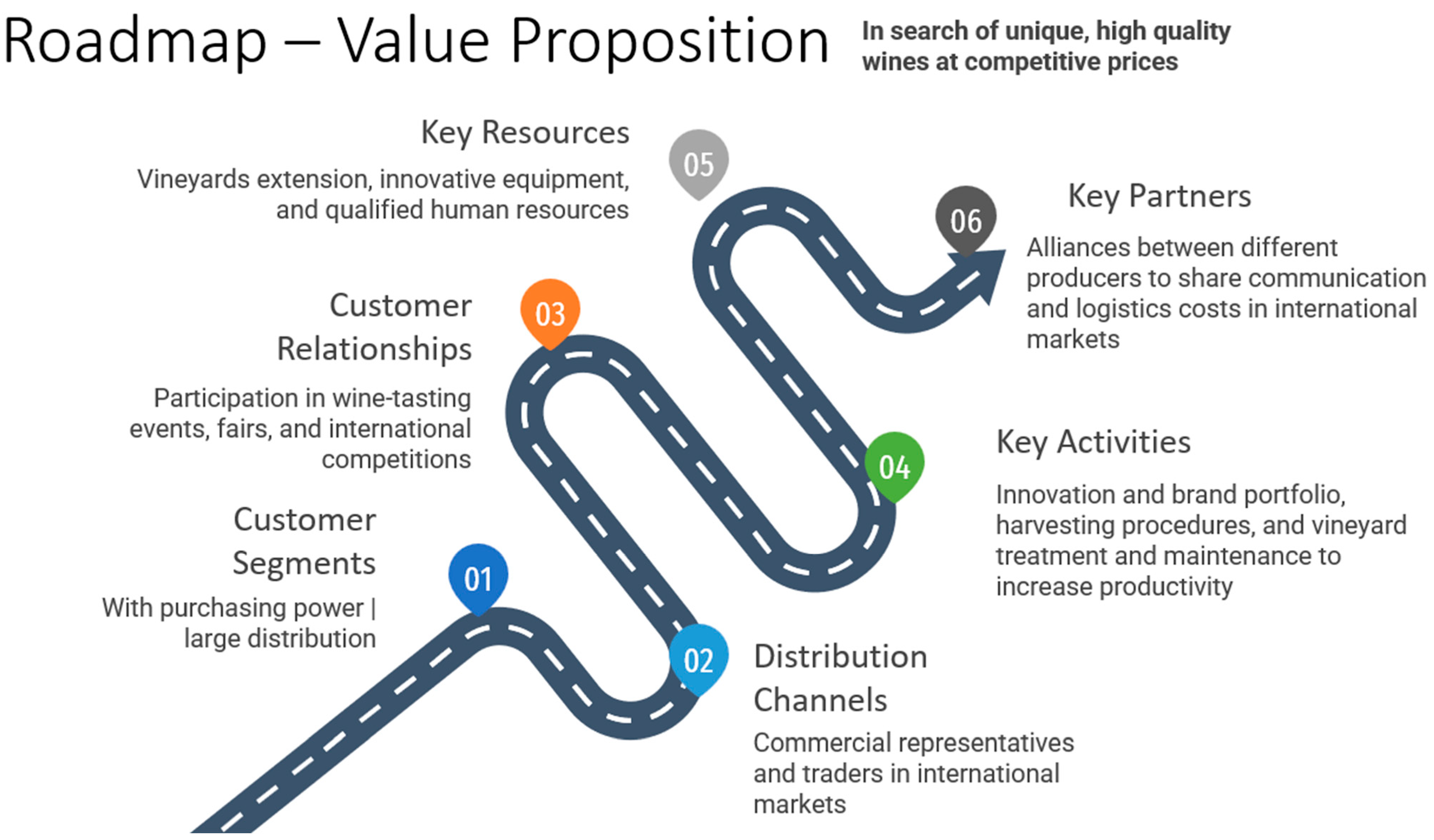

| Block/Macro Area | Component | Main Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Offer (What?) | Value Proposition | Unique, high-quality wines at competitive prices. |

| Client (Who?) | Customer Segments | Final customers—consumers with purchasing power—large distribution. |

| Channels | Commercial representatives and traders in international markets. | |

| Customer Relationship | Participation in wine-tasting events, fairs and international competitions. | |

| Infrastructure (How?) | Key Resources | Vineyard extension, innovative equipment and qualified human resources. |

| Key Activities | Innovation and brand portfolio, harvesting procedures and vineyard treatment and maintenance to increase productivity. | |

| Key Partners | Alliances between different producers to share communication and logistics costs in international markets. | |

| Financial Viability (How much?) | Cost Structure | Vineyard treatment equipment and human resources. |

| Revenue Streams | The scale of operations and high margins based on higher selling prices related to the unique quality of the wines. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Costa, T.; Teixeira, N.; Cravidão, M.; Galvão, R.; Nunes, S.; Mares, P. A Strategic Roadmap for the Wine Sector in the Setúbal Peninsula. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14040077

Costa T, Teixeira N, Cravidão M, Galvão R, Nunes S, Mares P. A Strategic Roadmap for the Wine Sector in the Setúbal Peninsula. Administrative Sciences. 2024; 14(4):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14040077

Chicago/Turabian StyleCosta, Teresa, Nuno Teixeira, Mário Cravidão, Rosa Galvão, Sandra Nunes, and Pedro Mares. 2024. "A Strategic Roadmap for the Wine Sector in the Setúbal Peninsula" Administrative Sciences 14, no. 4: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14040077

APA StyleCosta, T., Teixeira, N., Cravidão, M., Galvão, R., Nunes, S., & Mares, P. (2024). A Strategic Roadmap for the Wine Sector in the Setúbal Peninsula. Administrative Sciences, 14(4), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14040077