Standalone Valuation Method for Software-as-a-Service Operational Knowledge Derived from Human Intellectual Capital Qualitative Changes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. What Is Accounting Distortion?

2.2. Relationship between Digital Intangibles and Human Capital

2.3. Various Approaches to Digital Intangibles Valuation

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Approach

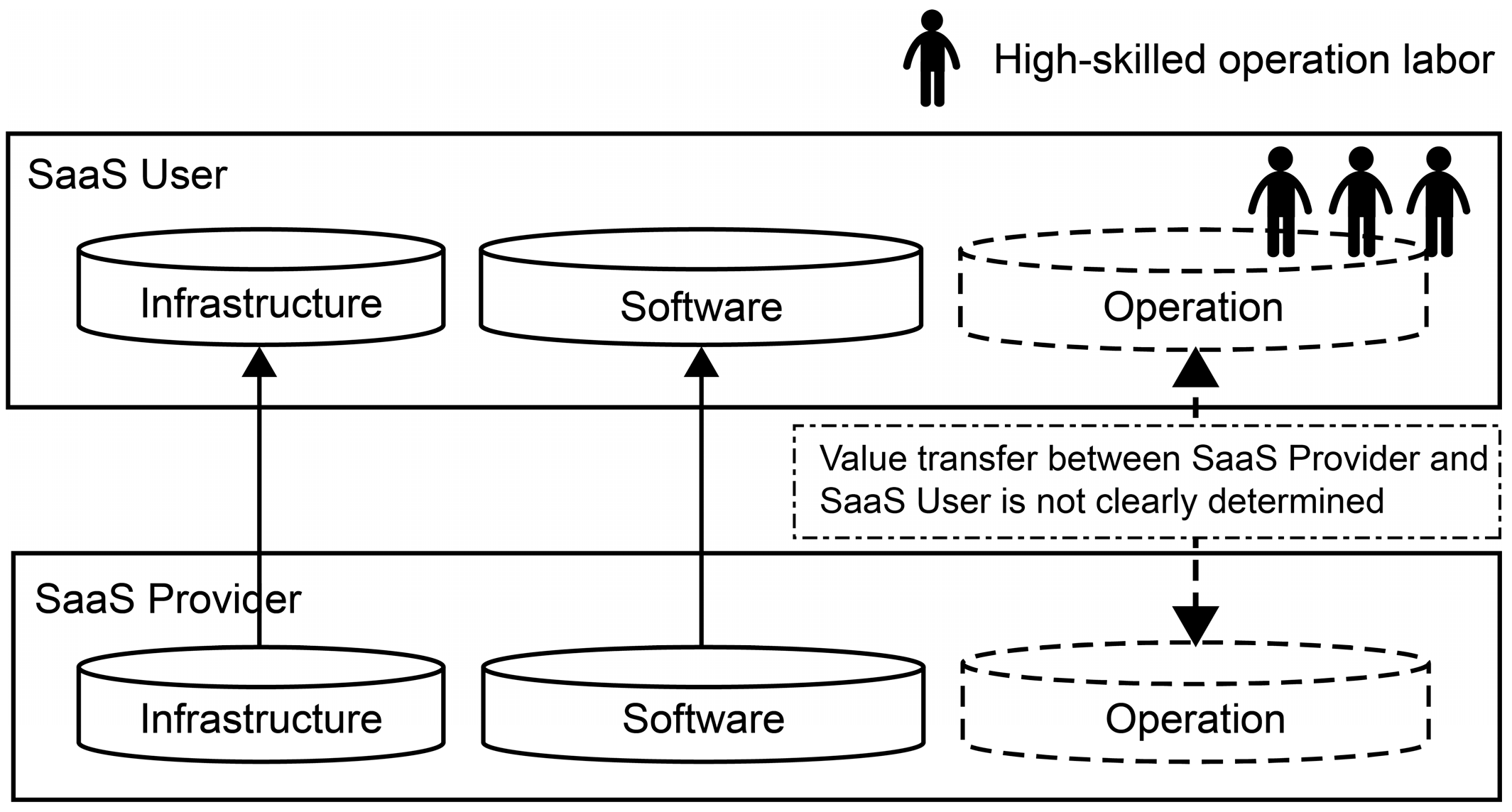

3.2. Assessment 1: Value Transfer between SaaS Sectors in the Japanese Digital Market

3.2.1. Purpose

3.2.2. Extraction Rule for SaaS-Advancing Companies

3.2.3. Digital Sectors to Which the 90 SaaS Companies Belong

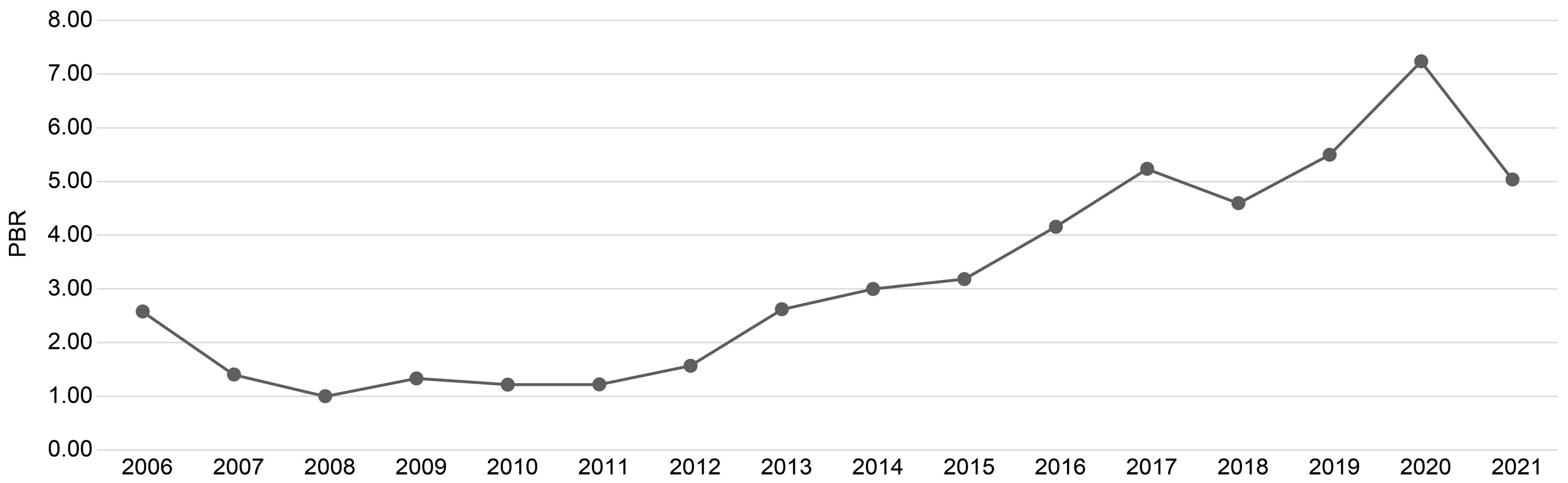

3.2.4. Setting a Benchmark

3.2.5. Standalone Value of Intangible Assets and Value Transfer between Digital Sectors

3.3. Assessment 2: Qualitative Changes in Capital Investment and Labor Investment

3.3.1. Purpose

3.3.2. Analysis Method

4. Results

4.1. Value Transfer Phenomenon between Digital Sectors

4.2. Calculation of the Value Transfer to SaaS Companies

4.3. Digital Service Productivity Investigation

- Case I: Do not recognize any intangible assets

- Output: Value added by tangible assets= Operating Income + Personnel Expenses + Rent + Taxes and Levies in Manufacturing, Selling, and General Administration Expenses + Parent Royalty + Depreciation

- Input: Tangible assets and number of employeesVariable Y_Case I = Value added by tangible assets ÷ tangible assetsVariable X_Case I = Value added by tangible assets ÷ number of employees

- Case II: Recognize both tangible and intangible assets

- Output: Value added by both tangible and intangible assets= Operating Income + Personnel Expenses + Rent + Taxes and Levies in Manufacturing, Selling, and General Administration Expenses + (Net) Intangible Fixed Assets + (Net) Digital Intellectual property + Depreciation + Amortization

- Input: Capital assets and number of employeesVariable Y_Case II = Value added by both tangible and intangible assets ÷ capital assetsVariable X_Case II = Value added by both tangible and intangible assets ÷ number of employees

4.4. Capital and Labor Investment and Productivity Investigation

5. Discussions

5.1. HTVI Recognition Is Dependent on SaaS Providers and Users

5.2. Qualitative Changes in Human Capital and Accounting Distortions

6. Conclusions

- It is necessary to benchmark the PBR multiples of SaaS companies in the same sector.

- On the basis of this benchmark, we define a PBR multiple range for a target company’s competitors.

- We calculate the ⊿PBR range by subtracting the benchmark from the PBR multiple range.

- The net assets of the target company are multiplied by the ⊿PBR range to estimate its enterprise value.

- Finally, it is important to perform β correction and value transfer rate allocation specific to the sector to which the target company belongs to ensure accurate valuation. By following these steps, a more precise valuation of a target company in the SaaS sector can be achieved.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmad, Nadim, and Paul Schreyer. 2016. Are GDP and Productivity Measures up to the Challenges of the Digital Economy? International Productivity Monitor 30: 4. [Google Scholar]

- Amiri, Ali. 2022. The Application Grouping Problem in Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) Networks. Information Technology and Management 23: 125–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbia, Giuseppe, Chiara Ghiringhelli, and Antonietta Mira. 2019. Estimation of Spatial Econometric Linear Models with Large Datasets: How Big Can Spatial Big Data Be? Regional Science and Urban Economics 76: 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badshah, Sher, Arif Ali Khan, and Bilal Khan. 2020. Towards Process Improvement in DevOps: A Systematic Literature Review. Paper presented at the Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering, Karlskrona, Sweden, June 15–16; pp. 427–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clohessy, Trevor, Thomas Acton, and Lorraine Morgan. 2020. The SaaS Payoff: Measuring the Business Value of Provisioning Software-as-a-Service Technologies. In Measuring the Business Value of Cloud Computing. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emvalomatis, Grigorios. 2017. Is Productivity Diverging in the EU? Evidence from 11 Member States. Empirical Economics 53: 1171–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, Christopher, Mark Graham, Laura Mann, Timothy Waema, and Nicolas Friederici. 2018. Digital Control in Value Chains: Challenges of Connectivity for East African Firms. Economic Geography 94: 68–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensen, Alexander R., and John Qi Dong. 2020. Hierarchical Business Value of Information Technology: Toward a Digital Innovation Value Chain. Information and Management 57: 103209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, Greg W., and Craig Kerr. 2019. Virtual Money Illusion and the Fundamental Value of Non-Fiat Anonymous Digital Payment Methods: Coining a (Bit of) Theory to Describe and Measure the Bitcoin Phenomenon. International Advances in Economic Research 25: 151–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, Hartini. 2011. Accounting for Intangible Assets, Firm Life Cycle and the Value Relevance of Intangible Assets. Doctoral dissertation, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Kourentzes, Nikolaos, and Fotios Petropoulos. 2016. Forecasting with Multivariate temporal aggregation: The Case of Promotional Modelling. International Journal of Production Economics 181: 145–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labaye, Eric, and Jaana Remes. 2015. Digital Technologies and the Global Economy’s Productivity Imperative. Digiworld Economic Journal 100: 47. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Cheng Y. 2011. The impact of accounting distortions on performance and growth measures. SSRN Electronic Journal. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1428202 (accessed on 7 April 2011). [CrossRef]

- OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2018. Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation-Economic Impact Assessment: Inclusive Framework on BEPS. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Shanshan. 2017. Harmfulness and Preventive Measures of Accounting Information Distortion. In 3rd International Conference on Economics, Social Science, Arts, Education and Management Engineering (ESSAEME 2017). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Atlantis Press, pp. 1113–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Qu, Jason, Ric Simes, and John O’Mahony. 2017. How do Digital Technologies Drive Economic Growth? Economic Record 93: 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, R. Srinivasa, K. R. Jayasimha, and Rajendra V. Nargundkar. 2020. Impact of Software as a Service (Saas) on Software Acquisition Process. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing 35: 757–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remes, Jaana, Jan Mischke, and Mekala Krishnan. 2018. Solving the Productivity Puzzle: The Role of Demand and the Promise of Digitization. International Productivity Monitor 35: 28–51. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, Adam, and Erik Brynjolfsson. 2016. Valuing Information Technology Related Intangible Assets. MIS Quarterly 40: 83–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsson, Johan, and Mats Magnusson. 2018. Collaboration Challenges in Digital Service Innovation Projects. International Journal of Automation Technology 12: 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriram, Srinivasaraghavan, Pradeep K. Chintagunta, and Ramya Neelamegham. 2006. Effects of Brand Preference, Product Attributes, and Marketing Mix Variables in Technology Product Markets. Marketing Science 25: 440–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ark, Bart. 2016. The Productivity Paradox of the New Digital Economy. International Productivity Monitor 31: 3. [Google Scholar]

- Visconti, Roberto Moro. 2020. The Valuation of Digital Intangibles: Technology, Marketing and Internet. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, Valerie, Gail Bowkett, and Isabelle Duchaine. 2018. All Companies are Technology Companies: Preparing Canadians with the Skills for a Digital Future. Canadian Public Policy 44: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zéghal, Daniel, and Anis Maaloul. 2011. The Accounting Treatment of Intangibles—A Critical Review of the Literature. Accounting Forum 35: 262–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Digital Sector | #SaaS@2020 | p (F ≤ f) | p (T ≤ t) | #Non-SaaS@2020 | p (F ≤ f) | p (T ≤ t) | #Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infrastructure Services | 12 | 29.3% | 0.093 ‡ | 0.483 †1 | 29 | 70.7% | 0.471 ‡ | 0.483 †7 | 41 |

| 13.3% | 4.8% | ||||||||

| BPO Services | 3 | 5.2% | 0.000 ‡ | 0.000 †2 | 55 | 94.8% | 0.396 ‡ | 0.436 †8 | 58 |

| 3.3% | 9.1% | ||||||||

| System Development | 16 | 8.2% | 0.034 ‡ | 0.001 †3 | 179 | 91.8% | 0.422 ‡ | 0.440 †9 | 195 |

| 17.8% | 29.5% | ||||||||

| Software Services | 43 | 22% | 0.011 ‡ | 0.000 †4 | 152 | 78% | 0.221 ‡ | 0.279 †10 | 195 |

| 47.8% | 25.1% | ||||||||

| Specialized Information Media | 9 | 5.4% | 0.000 ‡ | 0.000 †5 | 157 | 94.6% | 0.357 ‡ | 0.305 †11 | 166 |

| 10% | 25.9% | ||||||||

| Media Advertising Services | 7 | 17% | 0.074 ‡ | 0.065 †6 | 34 | 83% | 0.478 ‡ | 0.409 †12 | 41 |

| 7.8% | 5.6% | ||||||||

| #Total | 90 | 100% | 606 | 100% | 696 | ||||

| Population | TOPIX β@2020 (a) | PBR@2020 (b) | SaaS Intangible Value after Correction (c = b/a) | Intangible Allocation (d = c × Intra-sector Ratio) | Intangible Allocation (e = c × Ratio within Benchmark) | Value Transfer (Gross) (f = d − e) | Value Transfer % (f/F) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top 90 SaaS Companies | 90 | 1.16 | 7.23 | 6.23 (C) | NA | 6.23 (100%) | 2.82 (F = C−D) | |

| Infrastructure Services | 41 | 1.35 | 5.70 | 4.22 | 1.24 (29.3%) | 0.83 (13.3%) | 0.41 | 14.5% |

| BPO Services | 58 | 1.23 | 3.00 | 2.44 | 0.13 (5.2%) | 0.20 (3.3%) | ⊿0.07 | ⊿2.48% |

| System Development | 195 | 1.01 | 2.42 | 2.40 | 0.20 (8.2%) | 1.11 (17.8%) | ⊿0.91 | ⊿32.3% |

| Software Services | 195 | 1.04 | 4.90 | 4.71 | 1.04 (22%) | 2.98 (47.8%) | ⊿1.94 | ⊿68.8% |

| Specialized Information Media | 166 | 1.41 | 4.15 | 2.94 | 0.15 (5.4%) | 0.62 (10%) | ⊿0.47 | ⊿16.7% |

| Media Advertising Services | 41 | 0.97 | 3.73 | 3.85 | 0.65 (17%) | 0.49 (7.8%) | 0.16 | 5.6% |

| All Six Digital Sectors | 696 | 1.15 | 3.82 | 3.32 | 3.41 (D) | NA | ⊿2.82 | ⊿100% |

| Coefficient of X 2005–2012 | Coefficient of X 2013–2020 | Digital Sector | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Category 1 | Positive | Negative | System Development †, Software Services † |

| Category 2 | Negative | Positive | Infrastructure Services ‡, BPO Services † |

| Category 3 | Positive | Positive | Specialized Information Media †, Media Advertising Services ‡ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sakuma, S.; Furutani, T. Standalone Valuation Method for Software-as-a-Service Operational Knowledge Derived from Human Intellectual Capital Qualitative Changes. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14040071

Sakuma S, Furutani T. Standalone Valuation Method for Software-as-a-Service Operational Knowledge Derived from Human Intellectual Capital Qualitative Changes. Administrative Sciences. 2024; 14(4):71. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14040071

Chicago/Turabian StyleSakuma, Suguru, and Tomoyuki Furutani. 2024. "Standalone Valuation Method for Software-as-a-Service Operational Knowledge Derived from Human Intellectual Capital Qualitative Changes" Administrative Sciences 14, no. 4: 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14040071

APA StyleSakuma, S., & Furutani, T. (2024). Standalone Valuation Method for Software-as-a-Service Operational Knowledge Derived from Human Intellectual Capital Qualitative Changes. Administrative Sciences, 14(4), 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14040071