1. Introduction

Sustainable development presents a significant challenge due to variations in language and definitions depending on the ideological stance of sustainability advocates (

Mc Manus 1996). The term “sustainable development” has been criticized for its excessive use and lack of clarity by

Di Castri (

2000).

Structurally, the concept of sustainable development comprises two words: “sustainable” and “development.” Just as each of the two terms that form the idea of sustainable development, namely, “sustainable” and “development,” have been defined in various ways from different viewpoints, the concept of sustainable development has also been examined from multiple angles, resulting in numerous definitions of the concept (

Mensah 2019).

Sustainable development is traditionally defined as “economic development that meets the needs of current generations without sacrificing the needs of future generations” (

Unruh 2008). It defines commerce that preserves the natural world’s capacity to provide us with clean water, air, and vital natural resources in perpetuity while simultaneously achieving global equity through the elimination of poverty and the extreme disparities that currently exist on our planet (

Unruh 2008).

Achieving sustainable development is therefore a process that requires time and consensus-building, and the main aim of the process is to reconcile the twin goals of improving socio-economic conditions and enhancing environmental well-being.

In the public sector, sustainability is often linked to climate change and achieving environmental goals, such as those outlined in the Paris Agreement (

Edelmann and Virkar 2023).

Recent studies (

Holynska et al. 2023;

Burlacu et al. 2022;

Khalid et al. 2021;

Wretling and Balfors 2021) indicate that sustainability and sustainable development concepts are becoming more commonplace in the discipline of public administration (PA). The outcome is a natural consequence of the discipline’s focus on enhancing the positive impact of public interventions on society by strengthening the capacity of public institutions.

Sustainability is the capacity to maintain, support, and preserve something that is considered to be valuable (

Türke 2012).

In this regard, sustainability could play a vital role in contributing to administrative planning if it considers long-term planning, intergenerational equity, risk reduction, and resource conservation (

Burlacu et al. 2021).

One of the keys to redefining sustainable development is to extend its implications in the public sector and to analyze its impact on the public organizations and institutions that make up the public administration system. Thus, PA represents a crucial step towards affirming development models characterized by lasting sustainability (

Malandrino et al. 2019). This correlation is also supported by the UN 2030 Agenda (

United Nations 2024, p. 28), which includes PA as part of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), specifically SDG 16—Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions.

Since the meaning of sustainability for the public sector covers a broad plateau, such as the functioning of public organizations, public services, and policies, as well as the actions of stakeholders, including those of public bodies, national and international public structure efforts have led to numerous sets of sustainability indicators or the non-uniform use of instruments to measure these indicators.

The rigorous testing of claims about sustainable development is a challenge for public administration researchers. Thus, starting from the assumption that there is an important relationship between the concepts of sustainable development–sustainability of PA and the collaborative dimension of public administration (as an organization), the paper focuses on the case of Romanian PA, verifying this relationship through an exploratory study. The study evaluates the collaborative dimension indirectly by measuring organizational intelligence. This approach is supported by studies by

Sanderson et al. (

2001). Focusing on the pillars that lead to the development of an intelligent organization, the authors identify, on the one hand, the capacity of research to support learning processes, and on the other hand, the capacity to integrate research results obtained also through collaborative activities with other organizations. In this respect, and with reference to the current stage of development of the Romanian public administration, the paper aims to provide some answers to the following questions through empirical research:

- (i)

Do changes in mindset at the micro-organizational level and the implementation of these changes lead to a favorable organizational structure in terms of collaboration?

- (ii)

Do prerequisites exist for the development of organizational intelligence capable of understanding the dynamic, interdependent, and complex societal changes faced by the Romanian public administration, which can only be achieved through collaboration (with internal and the external organizational environment)?

To address these research questions, this article presents a case study that applies the

Lefter et al. (

2007) model from the specialized literature to measure organizational intelligence and draw conclusions about the sustainability of the targeted public organizations. This model can be applied to any type of organization, whether public or private. It includes items such as the organization’s strategic behavior, organizational climate, interdepartmental collaboration, interaction with the external environment, and the behavior and perception of its employees. The aim of evaluating with this model is to demonstrate that a public organization revealing sustainable development also implies a strong collaborative dimension.

The findings of this paper are expected to provide a new perspective on sustainable development in public administration by showing whether the dimension of collaboration could play a significant role in achieving sustainability goals.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Public Administration and Sustainable Development

We highlight two ways of linking sustainable development and public administration, proposed by

Renu Khator (

2007). In the first sense, sustainable development administration can mean administering sustainable development or finding strategies through which the ideal of sustainable development can be put to practice. This interpretation requires innovative research at all levels of government and in all walks of life. If the idea is to change our behavior and our priorities, we need integrative programs that can help us turn that idea into reality, an aspect that is also supported by

Sanderson et al. (

2001), as previously mentioned.

In the second sense, we can view sustainable development administration as a sub-field that focuses on sustaining the development of administration itself. In this context, research endeavors are needed to focus on the changing environment of PA and the strategies through which public administrators and public administrations can adapt to it (

Khator 2007).

We consider that our research is part of the second dimension of sustainability in PA because it is focused exactly on how the organizational structures that form the public administration system understand how to change in concordance with the environment to ensure sustainability. Based on these facts, we considered that the method of collaboration of these organizations that are forming the public administration system represent patterns of sustainable development. This statement is also supported by

Veryard (

2010, p. 17), who argues that the intelligence of a system is not a mere sum of the intelligence of its subsystems. In other words, in reference to the present study, organizational intelligence is not the sum of the intelligence of each resource at its disposal (employees, computers, etc.). The crucial element that transforms an organization into an intelligent public organization is its ability to collaborate (

Veryard 2010).

We also consider that PA as a field needs to be constantly reviewed and revised to maintain its vitality. PA is not a static field: The demands on the discipline have changed and will continue to change.

Sustainable development is a pressing concern for public organizations and governments striving to strike a harmonious equilibrium between economic, social, and environmental objectives (

Rădulescu et al. 2023), particularly in turbulent contexts (

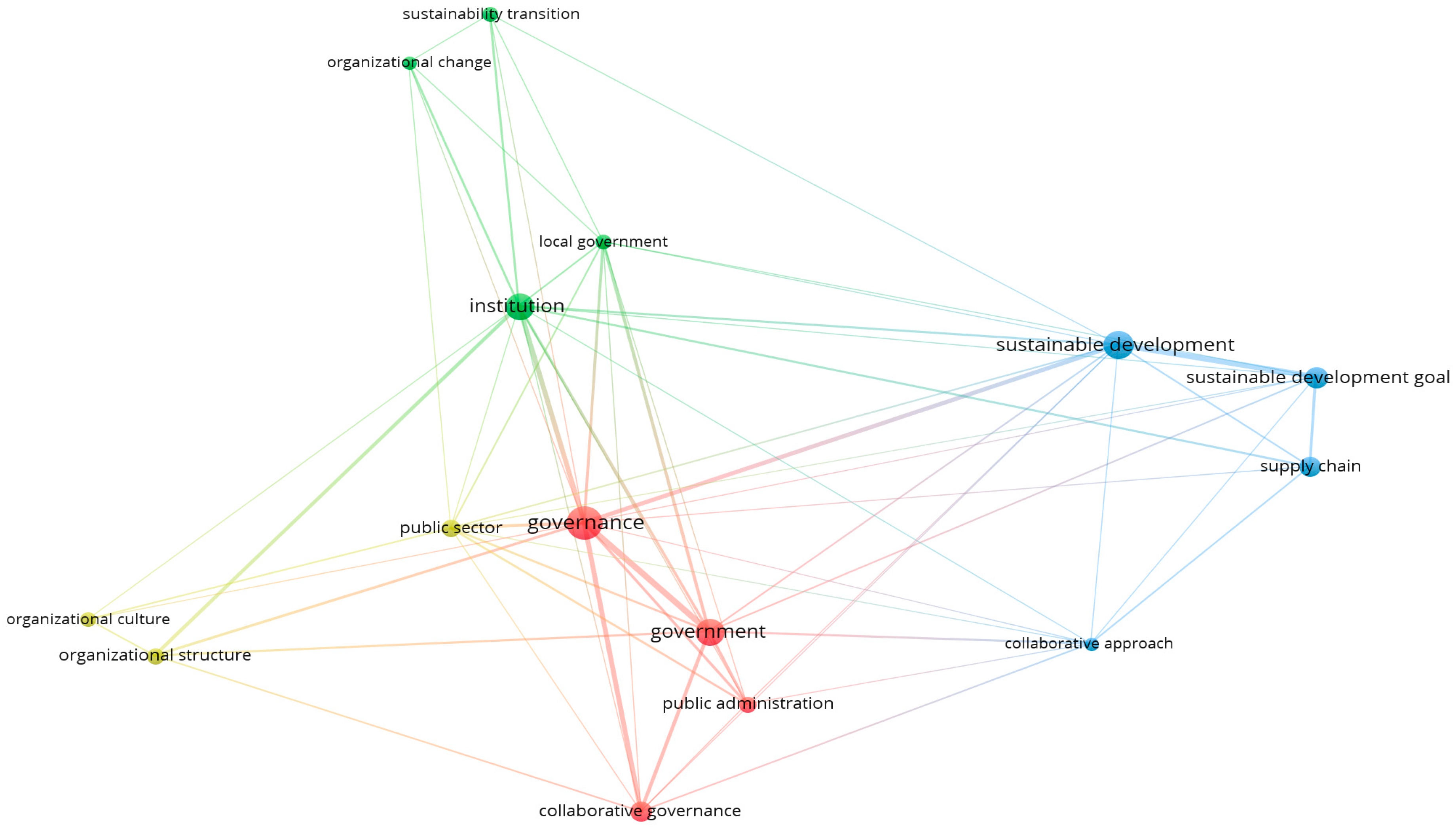

Hagelstam and Dias 2020), based on intelligent organizational development. For this reason, the most consistent theme to emerge from contemporary efforts to come to terms with sustainable development is the idea of integrating economic, social, and environmental considerations in decision-making across society. In the broadest sense, integration refers to all three pillars, to decisions made by individuals and by collectivities of all types and across all fields of societal endeavor. This is supported by the results of a bibliometric statistical analysis conducted using VOSviewer software in this work.

Analyzing visual representations emphasized the connections between concepts found in the Web of Science (WoS). The investigation uncovered features that demonstrate the substantial influence of the public administration and its approach to collaboration on sustainability and sustainable development, which translates into collaboration in the exercise of all institutional competences and in all areas of public policy.

Moreover, when the VOSviewer was applied to the Scopus database, it revealed that the extent that PA, as a dimension of sustainable development, relies on collaborative and decentralized networks and extensive practices of self- and co-governance, is essential to such societal integration (as also sustained by

Figure 2).

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 demonstrate that the literature in WoS and Scopus has given less attention to the concept of collaborative administration in relation to the trio of collaborative administration, sustainable administration/governance, and sustainable development.

Therefore, the added value of this article is to contribute to the advancement of knowledge on sustainable development and PA by conducting further research in this area with regard to the collaborative dimension.

2.2. New Organizational Culture of Public Administration: Collaboration

Globalization, European integration, decentralization, and integration of new technologies constitute challenges with which PA must cope and determine the adaptation of its structures to the evolution of the duties entrusted upon it by the political power, in relation to which administration from a historical perspective evolves in a direction favorable to the latter (

Alexandru 2008). These systemic changes are the result of transformations in the quality and quantity of human beings, as well as the stock of human knowledge, particularly as it applies to human control over nature, and the institutional framework that defines the deliberative incentive structure of a society (

Virtanen and Vakkuri 2015).

Public organizations should be resilient to these changes. This new capacity for in-depth understanding of the processes and mechanisms required to adapt an administration to social realities cannot be achieved and consolidated by means of changes in institutional or procedural arrangements alone, and all of them are included in the dimension of sustainable development.

However, the progress of this reform has not been complete and has been slowed down by the negative effects of the COVID-19 health crisis. For instance, in the EU, in this context, public administration is at the center of a new and comprehensive set of reforms and investments under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (

EU Council Regulation 2020)

1, with national objectives including increasing its sustainability through effective management, modern public services, and the expansion of information and communication technology.

From this perspective, attention shifts to the existence of a common organizational culture that motivates employees and offers the transfer of knowledge, enhancing their competencies and capabilities and promoting the crosspollination of ideas. “Today’s organizations, especially in the public sector which is characterized by the problems of bureaucracy and resistance to change and innovation, need to develop a positive organizational culture and a high level of flexibility to achieve continuous improvement and quality and be innovative and adaptive to changes” (

Xanthopoulou et al. 2022). Building on this idea, this type of public organization reflects a high degree of organizational intelligence, as understood through this concept (

Albrecht 2002;

Yaghoubi et al. 2010): The capacity of an enterprise to mobilize all of its available brain power and to focus that brain power on achieving its mission is based on three directions: (1) connection—for attracting knowledge, (2) interaction—for sharing knowledge, and (3) structuring—for extracting meaning.

William Halal (

2006) considers that organizational intelligence has the characteristics of the human intelligence, and he stated that the problem-solving capacity of organizations is a function of more than one cognitive subsystem. The five organizational subsystems include (1) organizational structure (who is authorized to make what decisions), (2) organizational culture (values and norms that guide action), (3) stakeholder relationships (the extent to which information is exchanged between diverse groups), (4) knowledge management (the type and amount of knowledge available), and (5) strategic processes (how this information leads to understanding and action).

An essential aspect in this context is the evaluation of the collaboration performance among organizations in the ecosystem to identify potential earnings and promote sustainability (

Graça and Camarinha-Mat 2021).

As observed by

Martínez Avila et al. (

2021), “collaboration refers to any shared activity between two or more organizations, working together to create public value collectively, rather than individually.”

As

Mudacumura et al. (

2006) explain, collaboration is an important factor for sustainability in public administration, through which public sector entities can work together in the pursuit of developmental functions for governance.

A common cause of the problems that arise within public organizations is represented by the deficit of collaboration between human resources. For instance, institutional work constantly evaluates values and behavioral norms, modifying and shaping cultural–cognitive, taken-for-granted values related to collaboration between parties (

Aaltonen and Turkulainen 2022). The collaboration is therefore a key factor of organizations because it provides the information and the knowledge needed to overcome the challenges the public administration is facing.

This deficit can be mitigated through a motivational strategy or a strategy focused on the transmission of knowledge, but it provides only routine changes, a solution consisting of “an organizational design opting for decentralization and networking of distributed intelligence” (

Departamento de Justicia, Generalitat de Catalunya 2010). It should be noted that the topic of intelligent organization in local public administration (LPA) is not frequently addressed in the literature. However, to implement modern organizational concepts in LPA, it is necessary to focus on both internal and external relations. This includes building long-term relationships with external partners while also prioritizing internal relations (

Godlewska-Majkowska and Komor 2019).

To assess the social aspect of administrative sustainability from the perspective of its internal environment, an exploratory study was conducted at a representative sample of public institutions in Romania. The study revealed the level of collaboration achieved by the organizations in their activities.

3. Methodology

To correlate sustainable development with collaborative public administration, a literature review was conducted in the second part of this study using VOSviewer, version 1.6.20. The review provides a comprehensive overview of relevant research published in the WoS and Scopus databases.

VOSviewer is a software application designed to generate, display, and investigate bibliometric maps of scientific research. It facilitates the analysis of networked bibliometric data comprising citation connections between publications or journals, collaborative alliances between researchers, and the evolution of relationships between scientific concepts (

van Eck and Waltman 2011). The steps involved in using this software were as follows: data collection, which entailed gathering relevant literature from publications in WoS and Scopus between 2010 and 2023; data processing, which involved removing duplicates, correcting errors, and ensuring consistency; importing data into VOSviewer; network construction, which was carried out using the binary counting method with a minimum term occurrence of 10; and visualization of networks based on the relationships between sustainable development and public administration, as well as sustainable development, collaborative governance, and organizational culture.

As there is currently no universal set of indicators to measure the sustainability of public organizations, the research method used was the deductive–indirect method. The assessment of the degree of collaboration, as shown with the Halal model, is derived from the measurement of organizational intelligence, and the relationships between stakeholders are considered one of the five cognitive subsystems of organizational intelligence.

In turn, collaboration can negatively or positively influence the sustainability knowledge assets of organizations, as the process of building and sustaining that intangible asset is achieved through relationships with employees, suppliers, customers, competitors, clients, and the community in which the organization operates. From this collaboration arises the added value that is actually one of the facets of the functionality and sustainability of the interventions of the public entity (

Yaghoubi et al. 2010).

The empirical analysis conducted consisted of various steps. The initial step was to define the research object, which is the local public administration system. It is important to note that the focus of observation was on these authorities because they are responsible for developing and implementing local interventions that ensure sustainable development of the communities they represent.

In order to address the lack of information and to reduce the need for a larger research team, we administered an integrated questionnaire to a few selected local public administrations, in particular, municipalities. This approach enabled us to assess the level of collaboration within these entities and identify the boundaries of this collaboration in relation to evaluating the sustainable dimension of public administration.

To ensure a representative sample, we applied a set of study criteria. These included a general–functional criterion that considered the level of local development of the territorial–administrative unit (TAU), as well as a territorial criterion. Romania is divided into TAUs, including counties, municipalities, cities, and communes. Each county includes municipalities, cities, and communes. As of 2022, there are 41 counties, 319 cities (in 103 municipalities, including Bucharest Municipality, the capital of Romania), and 2862 communes (

INS 2024). We chose a homogeneous group of the most developed TAUs based on their quality of life, reflecting their sustainable development. Based on the causal relationship between sustainable development and sustainable public administration, we selected a homogeneous group (same category of TAUs) of the most developed TAUs from the perspective of sustainable development reflected by quality of life. Counties were eliminated because they have more categories of TAUs, and municipalities were chosen because they are more developed (including from a functional perspective) than cities and commons.

Thus, we selected one municipality from each of the eight regions of Romania, and with reference to the functional criterion, chose ones that have the most important functions and are the center of trade, economic, and demographic flows:

2 Bucharest, Timisoara, Cluj-Napoca, Craiova, Iasi, Brasov, Ploieşti, and Constanța.

The selection of the municipalities was based on the results of a survey conducted in the context of a regionalization and decentralization process initiated by the Government of Romania (

CONREG 2013) at the request of the authorities in all future development regions, and it showed that people from different areas of the country want these municipalities to become residence regions.

The online questionnaire for the exploratory analysis was administered in 2022. To answer the questions, a working group was established at the level of each local public authority in the selected municipalities. The group consisted of individuals holding middle management positions within each organization.

The questionnaire includes organizational intelligence indicators that consider the dimensions of sustainability in terms of the internal environment of the organization. It assesses the operation of public organizations, including leaders’ ability to communicate the organization’s objectives and stakeholder participation. It also evaluates public policies and services, as well as the actions of stakeholders, such as the effectiveness of services provided by the public body and the support provided by the organization for the civic commitment of employees and citizens.

Of the existing models in the literature for measuring organizational intelligence, in the research conducted herein the model by

Lefter et al. (

2007, pp. 42–44),was used, which includes 7 components and 49 items (see

Appendix A). The questionnaire can also be found in

Prejmerean and Vasilache (

2007), where it is applied to higher education institutions.

In the final stage of the methodology, quantitative and qualitative analyses were conducted on the recorded information (see

Appendix B). The results were discussed, and conclusions were formulated regarding the collaborative dimension and the sustainability of the analyzed public organizations.

4. Results

Prior to analyzing the studied dimensions, it is important to note that the collection of information presented certain difficulties. For instance, the questionnaire was only applicable in seven out of the eight selected municipalities (excluding Iași Municipality). Additionally, some questionnaires were only partially completed, which limited the extent to which certain aspects could be covered in this stage of the research. This limitation is also significant for this study.

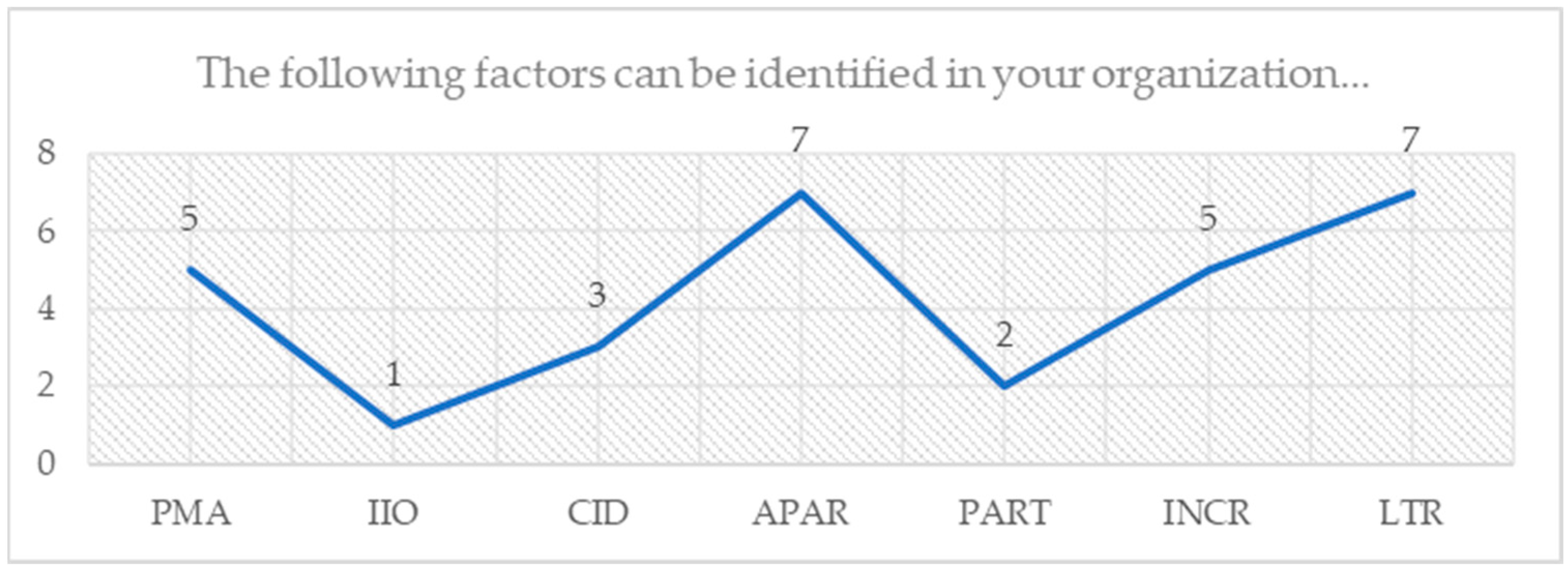

Regarding the first dimension, “strategic vision,” in

Figure 3, we see that apart from “environmental scanning” and “statement of direction,” three components fell on our scale from 0 to 7. The average was around 4, indicating an average level of achievement of these objectives in the selected sample of public organizations. The lowest scores obtained were those of the value proposition and the identification and promotion of leaders.

To the results of the evaluation of “joining the component members of the organization to a common fate” are presented in

Figure 4.

On the same scale from 0 to 7, it was observed that the relative maximum levels were reached by “sense of belonging” and “projected long-lasting relationship with the organization,” a result confirmed by the location of the two components “sharing plans and priorities between management and employees” and “employees’ belief in the organization’s success” around the mean value of the interval (0–7). The low value of the component “employee–management partnership,” a situation frequently encountered in Romanian public entities, draws implicit difficulties in understanding the organizational idea at all levels of the organization (“understanding of the organizational idea throughout the organization”).

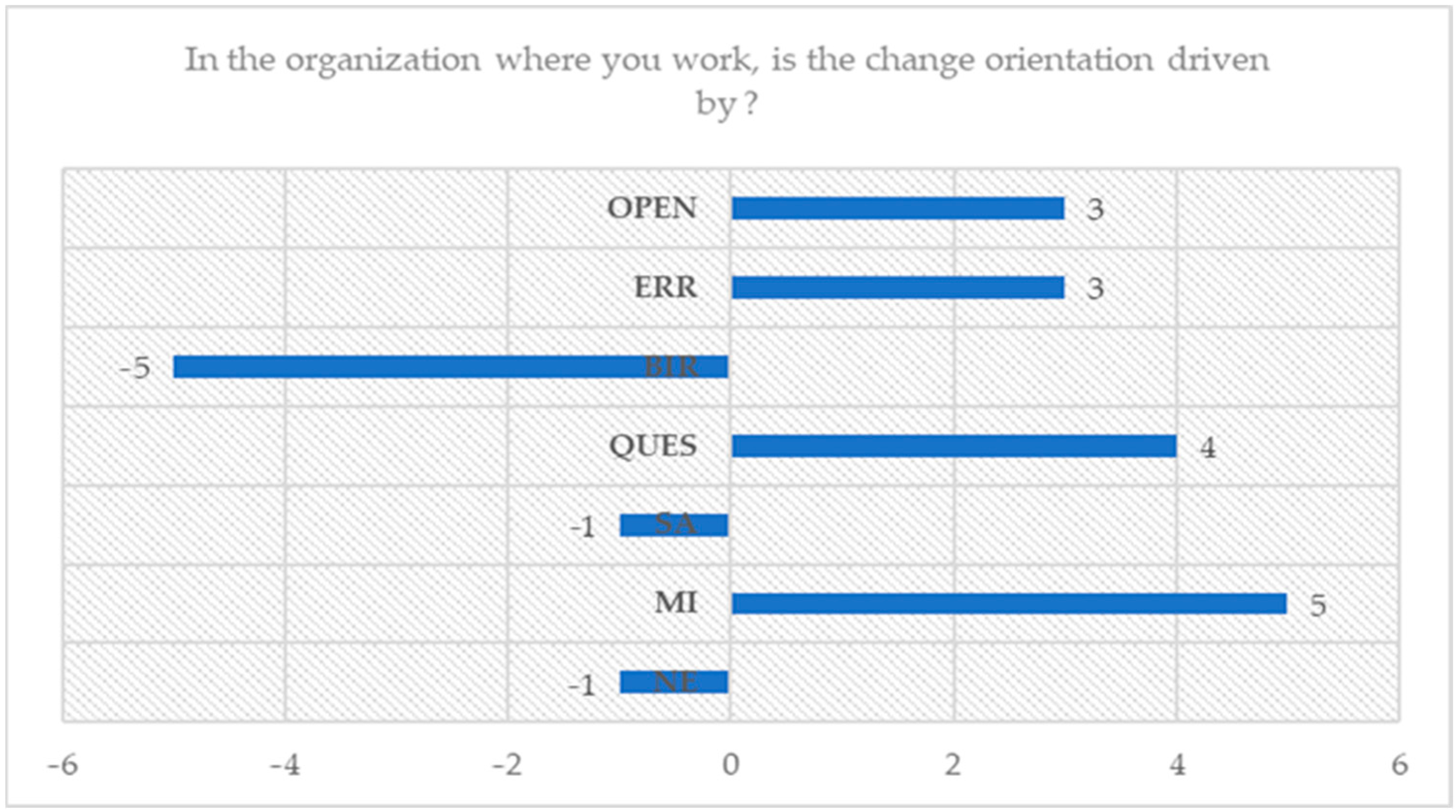

The evaluation of the component “orientation change” (

Figure 5) indicates that the maintenance of the principal factor in the public sector that opposes change in an organization, "bureaucracy," yielded a negative value near the maximum, followed closely by “lack of motivation of human resources” and “low supply of new services to citizens.” On the other hand, the other pro-change parameters were about average. The analysis of the values of these items shows that the process of orientation to change and innovation in the analyzed public organizations is being maintained in a latent state.

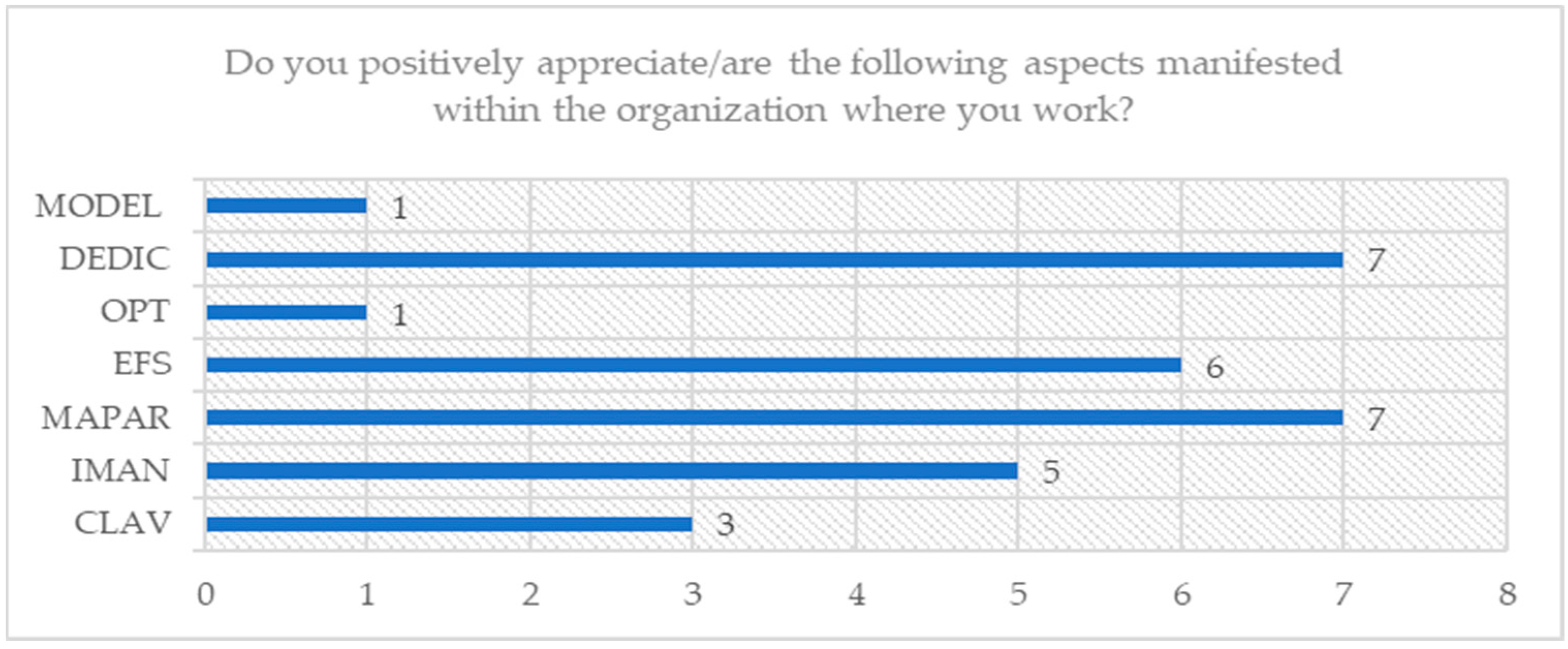

The evaluation (

Figure 6) of the fourth component of organizational intelligence, “heart and soul,” showed maximum values for “pride taken in belonging to the organization,” “willingness on the part of the employees to exert extra effort in building organizational success,” and “management commitment.” For the Romanian public sector, this represents an encouraging consolidation of the values of “conscience” and “commitment of human resources of local public administration,” something that has been difficult to achieve due to the long process of reform that has been and continues to be undertaken.

There low-support vectors of this component remain, namely, for “overall quality of work life as perceived by the employees,” “optimism regarding the future of employees’ careers in the organization,” and “perception of managers as role models.”

These aspects point to a delicate balance that is found in relation to the mutual relationship between human resources and the institution and the degree of commitment, which can quickly experience a significant decrease.

In

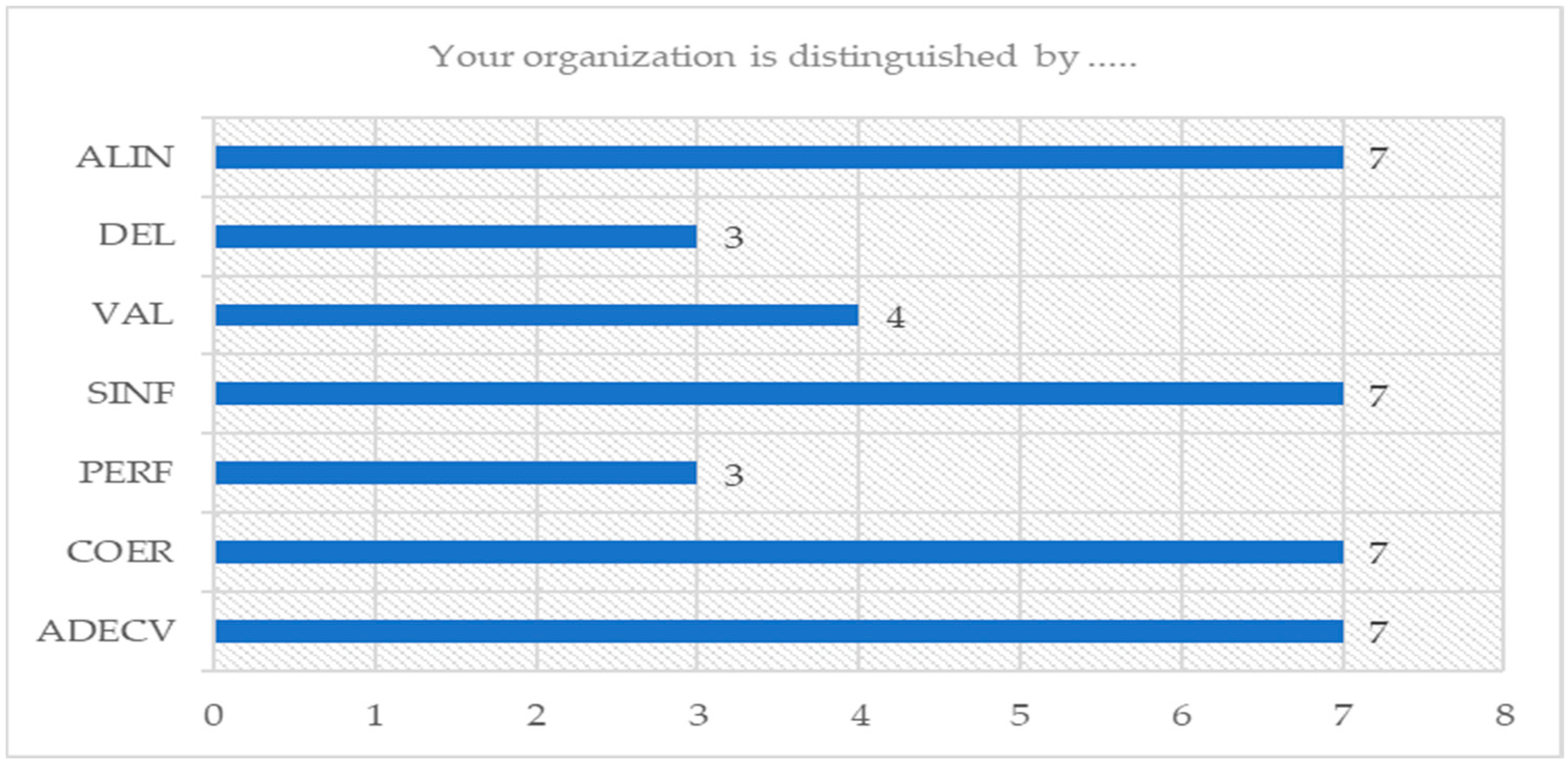

Figure 7, it can be seen that the main factors of alignment were those specific to public organizations whose organization and functioning are strictly regulated by formal and institutional rules, namely, “appropriateness of the organizational structure to the mission,” “making sense of rules and policies compared to priorities,” and “alignment of the department’s mission so as to facilitate cooperation.” These factors are also supported by the existence of a dimension that would allow public organizations to adapt to novelty and that is reflected by the maximum value recorded for the “information systems as facilitators” component. The other components remained close to the average value of the interval (0,7).

Figure 8 illustrates that knowledge dissemination within organizations can be challenging. Only two of the recorded mechanisms for dissemination achieved maximum values: “support from information systems for knowledge flows” and “support from continuous learning programs.”

However, this may be quite a formal rule due to the need to comply with regulations imposed by the law (mandatory continuous training of human resources in public administration and alignment with standards imposed by quality systems) and not by a new organizational culture and performance.

Although there is a tendency to approximate the organizational levels of management, such as the operational level, based on mutual recognition of the qualities of each level, this trend has failed to break down the traditional organizational boundaries that are felt in local government.

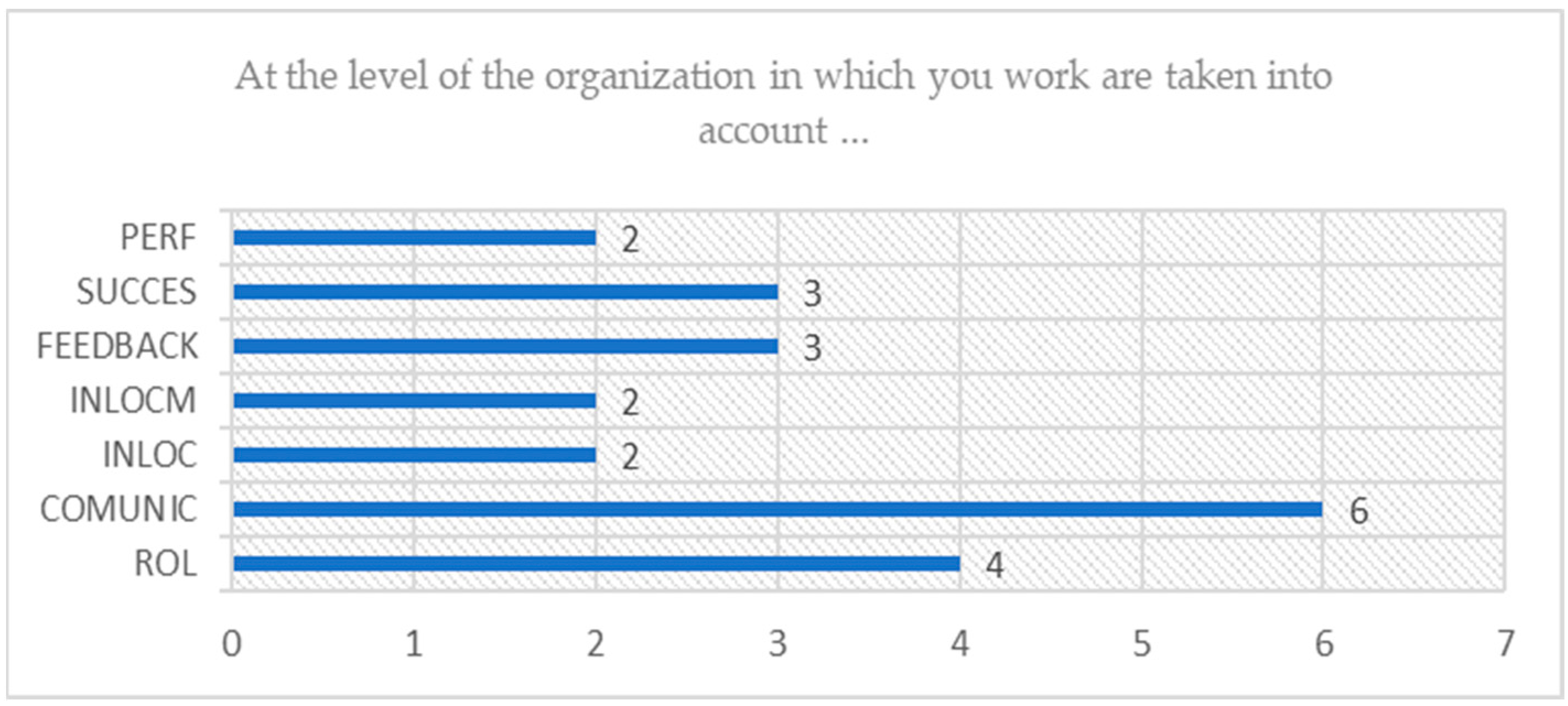

The evaluation of the last component of organizational intelligence, “performance pressure,” indicates the existence of a significant demand in terms of the level of performance that human resources need to achieve in these organizations, but a medium level of understanding of the role and responsibilities in organizations from its members was observed.

“Employees’ perception that their individual performance contributes to the organization’s success” was low, as was “employees’ perception that career success is influenced by performance.”

Methods of improving organizational activity by replacing non-performing staff regardless of the organizational level have not been applied, which is evidenced by the slow progress in the implementation of reforms regarding the management of civil servants and the civil service.

It can be remarked on that the organizational network is not operating at optimum values (

Figure 9). The recorded items of this component reflect the need to redesign the management of the whole system (informational, organizational methodological, and decision-making).

The results of the research confirm for the analyzed Romanian PA the crystallization of an organizational design that opts for decentralization and networking of distributed intelligence that does not operate in ideal parameters to ensure a satisfactory level of sustainability of its interventions in organizations and society.

Organizational behavior reflects disrupted interdependencies between the dimensions of sustainability in terms of the internal environment of the organization: the functioning of organizations, policies, and the services provided by the actions of stakeholders.

Despite the existence of well-trained human resources, which continue the tradition of loyalty, dedication, and high professionalism specific to the activity of public authorities, the state of inflexibility and excessive bureaucracy in the face of change and innovation processes barriers is perpetuated, which is reflected in the low level of cooperation between organizational levels and in general between the relations of stakeholders.

The difficulty with ensuring a sustainable and favorable porous functioning of organizational borders is due to the manifestation of a spirit of task preservation in the top management of these entities, which is reflected by the poor judgement of the partnership between the management and the operational level, the perception of managers as role models, the delegation of authority, the motivation of employees to complete their tasks, etc.

5. Discussion

The aim of this article was to assess the significance of collaborative public administration in promoting sustainable development. In the absence of an established model for the analysis of collaborative administration, the measurement of collaboration as an organizational model was based on the measurement of organizational intelligence.

The case study provides empirical evidence of the influence of organizational intelligence and, hence, collaboration, on institutional sustainability. Overall, the findings confirm that organizational intelligence is negatively influenced by, among other things, the inflexibility and excessive bureaucracy typical of public administration, the gap between strategic and operational management, low levels of participative management, low levels of staff motivation, compliance with the rules at the expense of results-oriented management, and low levels of understanding of individual contribution to organizational progress.

However, to comprehend the links between organizational intelligence and the collaborative dimension, the questionnaire responses were categorized in

Table 1 as strengths (item value ≥ 5) and weaknesses (item value < 5) based on a set of defining benchmarks for each type of organization (management, collaborative dimension, internal processes and organization, human resources, and organizational climate).

Table 1 illustrates that the group of seven local authorities was characterized by strong strategic management but weak and inconsistent leadership with limited ability to drive change despite a desire to improve (TEND = 4). The internal environment showed a low level of cooperation (PART = 2; CID = 3; FEEDBACK = 3; POR = −2) and an incomplete appreciation of staff knowledge (TACIT = 4), which may explain the limited delegation of authority (DEL = 3).

The collaborative dimension relies on human resources that are loyal to the organization and dedicated to its mission and that have a sense of vocation. However, weak leadership can contribute to a breakdown in relations between managers and employees, resulting in a less favorable organizational climate and demotivated staff.

Bureaucracy is a common feature of public organizations in the target group. Although employees are aware of their goals, their accountability is low in case of failure. The organization is not perceived as a unified whole, and despite coherent internal processes that encourage innovation, employees fail to add value.

However, the premises of adequate collaboration in the internal organizational environment leading to an increase in the level of organizational intelligence by facilitating cooperation (ALIN = 7) and adequate information flow (SINF = 7) are ensured. Added to these strengths is good communication between top management and employees, but this seems rather one-way (top-down) regarding objectives and expectations, plans and priorities, and the facilitation of the dissemination of knowledge.

Therefore, by referring to the questionnaire items that recorded low values and, at the same time, answering the first research question, the findings confirm that these negative effects can be counteracted by improving organizational management and leadership, thus increasing the sustainability of the targeted public institutions.

Mainly, the mindset at the cognitive level can be changed (especially the mentality of top management), change management and organizational innovation can be promoted, and internal communication can be promoted as a tool for institutional integration, which can be achieved through measures to modernize public organizations and make them capable of meeting the demands of ensuring their sustainability. In addition, there is a need for continuous evaluation of organizational performance, which is closely linked to individual performance, and for separate evaluation of the two.

Therefore, in relation to the research questions, it can be empirically confirmed that changes in mindset at the cognitive level and the implementation of these changes lead to the development of administrative collaboration.

Table 2 summarizes the unitary answers (value of item = 6 or 7) found for the analyzed public organizations regarding the second research question.

For the “change orientation” dimension, no item registered a common direction (item value ≥ 6) for the analyzed public institutions. Therefore, the common “package” for the seven local public administrations analyzed includes management commitment, good strategic planning and organization, policy coherence (aligned with sustainable development), and a dedicated and high-performing professional body.

The success of increasing the organizational intelligence and sustainability of these organizations lies in their management, particularly at the top level. Once consolidated, the management can develop the collaborative dimension, motivate the staff, and reduce bureaucracy.

These unitary results only partially support the second research question, since, according to the methodology used for the case study, they cannot be extrapolated for the entire Romanian public administration system. However, the seven large administrative centers represent significant TAUs, including the capital of Romania, and serve as sustainable development hubs for a vast territorial area of influence. Therefore, in terms of change management principles, models, practices, and standards, the selected target group for the case study should extend at least to the local public administrations in the area of influence.

Considering that an intelligent organization should be created to improve its ability to respond to changes in the environment as well as strengthen partnerships and collaborations with other entities (

Hovland 2003;

Godlewska-Majkowska and Komor 2019), it follows that the reform measures can multiply good practices at the level of some public institutions and thus ensure the premises for the development of the organizational intelligence of public institutions. However, this is not only achieved through collaboration: The collaborative dimension also facilitates the development of this intelligence.

Correlating the research results with the theoretical part, we observed that the model for measuring organizational intelligence using Lefter et al.’s model was not sufficient to measure the direct causality of the relationship between sustainable development–institutional sustainability–collaborative dimension. By referring to the good results obtained in the communities they represent, we deduced that, although these public organizations had a reduced collaborative dimension, this was partially compensated for by the effort and dedication of the employees. The model proposed by Lefter et al. includes operational dimensions that aid in identifying institutional measures that, if implemented, can strengthen this relationship. The main measure of this type is the development of mindsets at the cognitive level (especially at the top management level). However, this change cannot be achieved in a very short time but rather, according to the exploratory study, is the result of the accumulation over a longer period of time of certain PA reform/modernization measures.

Despite the notable strengths of this research, there are some limitations. To begin with, it should be noted that “organizational intelligence” is a complex term that covers a wide range of dimensions, levels, and aspects. As such, it poses challenges when attempting to measure and statistically analyze the concept. The sample size of this study is insufficient to draw general conclusions regarding the level of sustainability of the whole public administration system, especially in terms of collaboration. In addition, the use of an online questionnaire led to certain obstacles such as lack of control over the respondents’ environment and incomplete questionnaires.

6. Conclusions

Sustainable development is a complex, overly fluid, and contested concept (

Beren 2007) with no universally accepted definition.

However, the contribution of the literature in the field of public administration, as revealed by our bibliometric research, outlines the interdependence of this concept with other concepts of interest, and this article advances a new research direction in the sense of explaining the relationship between sustainable development–institutional sustainability–collaborative dimension on operational items and how it concerns the concept of organizational intelligence.

With this paper, we tried to bring a new perspective to the debate on sustainable development by analyzing a micro-dimension of public administration—more precisely, the collaborative dimension—considering both the internal and external environment of an organization. We started from the theoretically validated premise that the collaboration between organizational units (local authorities) of the public administration system is an important step towards achieving the objective of sustainable development.

The exploratory study carried out partially confirms the presumptions of the paper.

For the first research question, it is important to note that mindset changes at the employee level can be significant. However, the most important change must occur at the top management level to ensure leadership capable of consistently developing the collaborative dimension regardless of whether the organizational context is favorable or unfavorable. It is not enough to simply state the organization’s priorities and objectives through one-way communication. With the benefit of a professional and dedicated human resource, top management needs to give wider recognition to the contribution and skills of employees, including through delegation of authority, which will ensure a higher level of motivation.

Concerning the second research question, the case study uncovered that several pillars of organizational intelligence were particularly robust for the seven local authorities. These include strategic planning, organization and capacity, and commitment and engagement of human resources. On the other hand, other pillars were affected by weak leadership and a collaborative dimension that was not complete either within the organizations or with other entities from the external organizational environment. Even if the public organizations selected for the target group were real vectors of change for the administrations in their (territorial) area of influence as well, institutional development at the level of the whole administrative system requires broader measures to modernize this system and to coagulate this organizational intelligence of each public institution.

In summary, the research also highlighted some key factors for strengthening the sustainability of PA. In addition to the collaborative dimension, other key factors include reducing bureaucracy, operational alignment of objectives, cognitive mindset (especially at top management level), linking organizational and individual performance, and innovation.

As a general conclusion, the research results in relation to the two research questions show that the collaborative dimension requires future research directions for the development of a specific model to clearly establish a direct causality in the relationship between sustainable development–institutional sustainability–collaborative dimension, possibly by adding other organizational dimensions and items to the design model proposed by Lefter et al. for organizational intelligence and/or by using other research methods.

Since the exploratory study allowed for the identification of positive action plans that accelerate the consolidation of the sustainability of public administration and its actions and, implicitly, sustainable development, the authors plan to extend the study to at least 41 municipalities from 41 counties in Romania, considering the country’s administrative structure.

The conclusions of this article will be the subject of future research, the results of which will contribute to strengthening the overall picture of the sustainability of the analyzed organizations in particular and Romanian public administration in general.