An Organizational Framework for Microenterprises to Face Exogenous Shocks: A Viable System Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

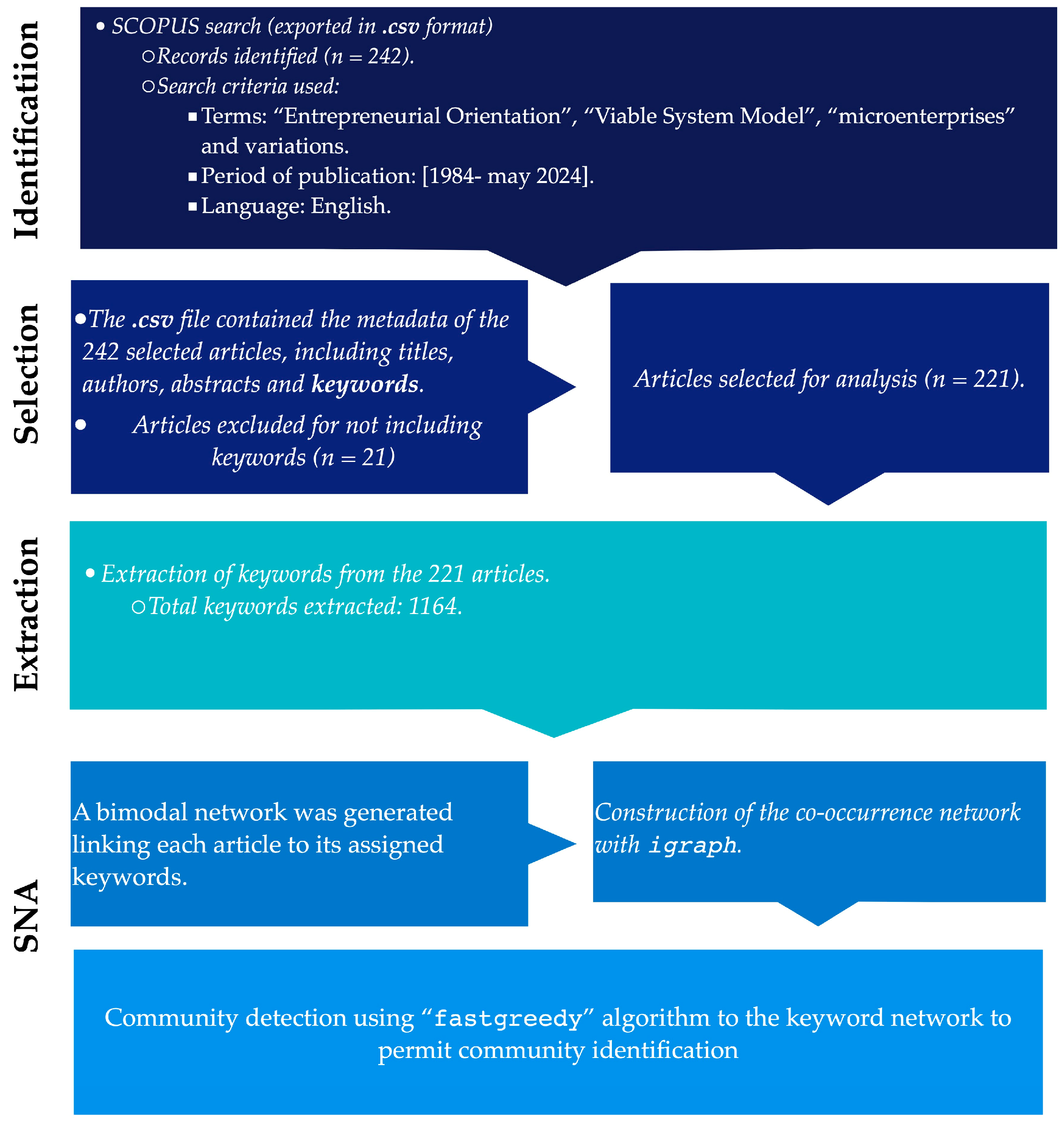

3. Methodology

- Keyword definition: The keyword analysis protocol focused on the contexts of EO, microenterprises, and the VSM.

- Search strategy: The following combinations were used to search titles, abstracts, and keywords: “entrepreneurial orientation factors and microbusiness performance” ((“entrepreneurial orientation AND factors” OR “entrepreneurial orientation dimensions” OR “entrepreneurial orientation AND factors” OR “entrepreneurial orientation factors” OR “entrepreneurial orientation AND innovation” OR “microbusiness entrepreneurial orientation”) AND (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“entrepreneurial AND orientation”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“system AND thinking”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“problem AND structuring AND methods”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“cybernetics”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“viable AND system AND model”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“microbusiness”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“exogenous shocks” OR “environmental disruptions” AND “organizational adaptation”))). The search focused on identifying the application of strategic factors of systems science, especially organizational cybernetics, to problems linked to the survival and institutionalization of microenterprises. In addition, the search strategy integrated the systems thinking ideas of Sánchez-García et al. (2020) and Romero-García et al. (2019).

- Inclusion criteria: publications with a systemic approach considering EO dimensions and their effects on SME performance, including investigations from around the world.

- Set period and published language: Our search strategy in SCOPUS yielded articles from 1984 to May 2024 published in English.

- After an initial examination of publication density pertinent to the research objectives, articles discussing aspects of non-business fundamentals were omitted, as these elements did not directly pertain to our examination of microenterprise survival from an organizational viewpoint.

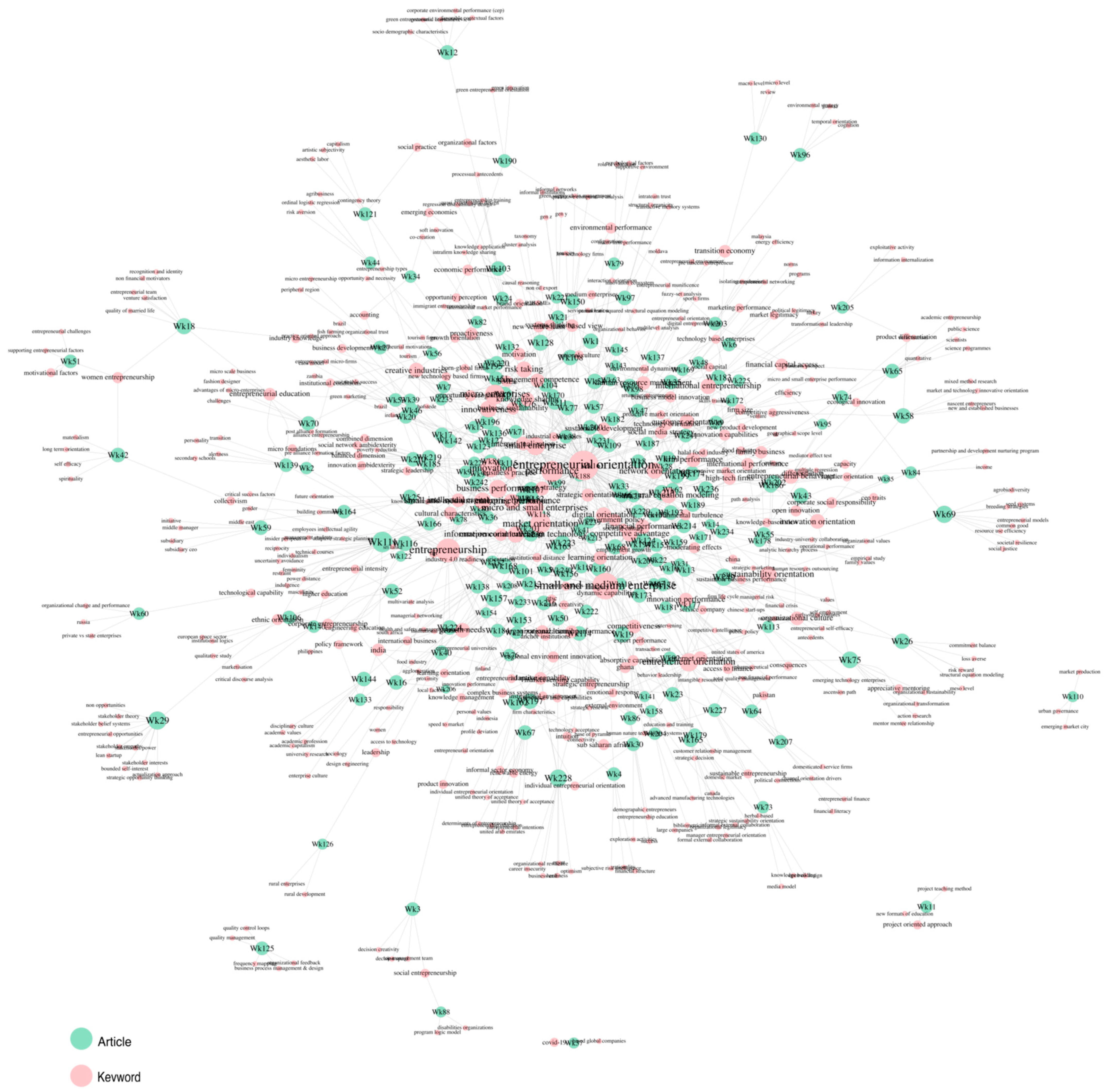

- Network Analysis: The analysis starts with a bipartite adjacency matrix with dimensions , where m is the number of articles, and n is the number of keywords.

- A relationship exists if an item i contains a keyword j, which is expressed as and 0 otherwise.

- The bipartite network is transformed into a one-mode network to generate the co-occurrence network . The product of is calculated, and indicates when particular words co-occur.

- Based on , we define , an undirected graph in which V is the number of vertices or codewords and E is the set of relations.

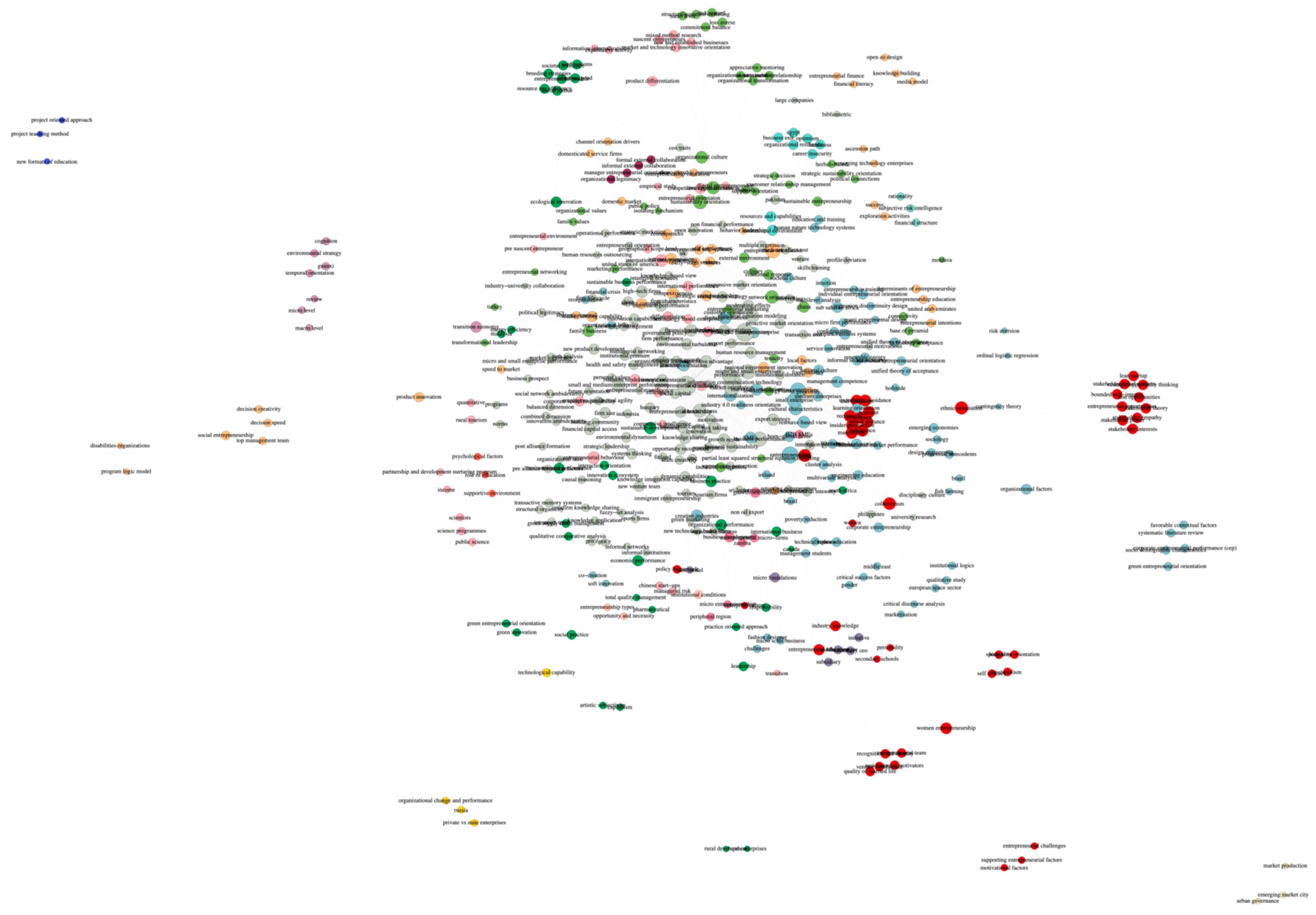

- Identification of EO factors: With the fast-greedy algorithm (Kolaczyk and Csárdi 2014), it is considered that each word starts in , and iterations lead to clustering to merge pairs of communities and to maximize the modularity . The recognized communities answer several critical questions related to OE and its application in microenterprises to cope with exogenous shocks:

- ◯

- 1. What key themes and concepts have been studied in the literature about EO and its impact on microenterprises?

- ◯

- 2. What are the main critical factors affecting microenterprises, and how do they relate to EO?

- ◯

- 3. Applicability of VSM: How can the identified EO factors be implemented through the VSM in a microenterprise context?

- It is worth mentioning that the SNA was implemented using the igraph package (Kolaczyk and Csárdi 2014) for R (Version 2024.09.1+394).

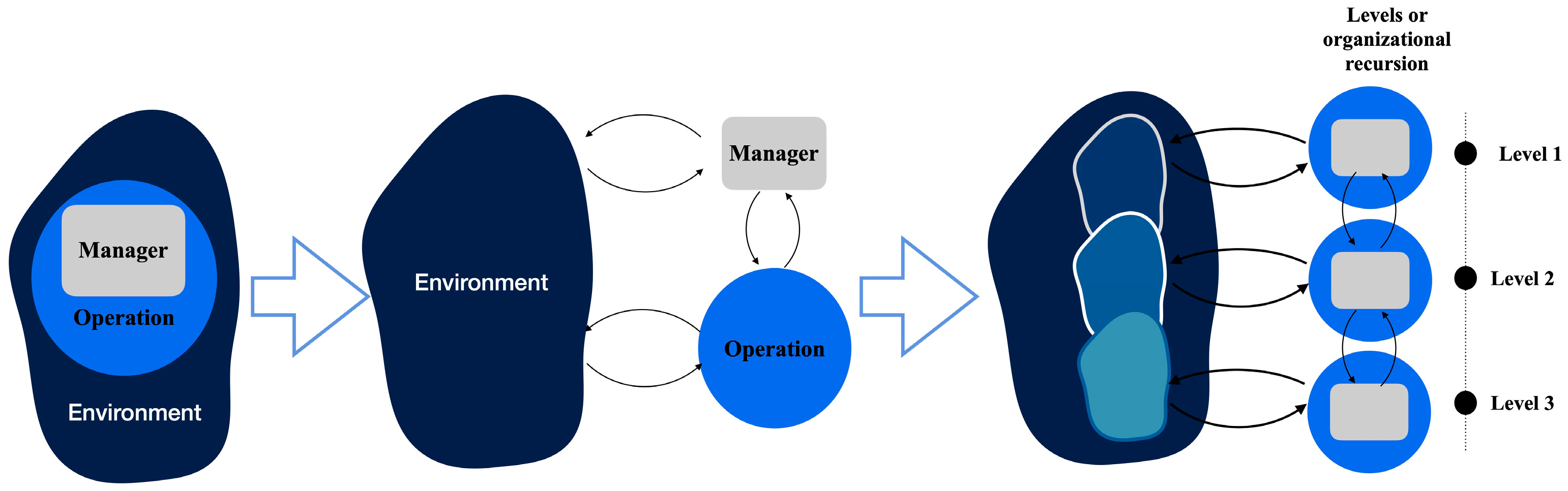

- Identify the purpose and recursive structure, also known as the unfolding complexity.

- Analyze the current business setting and provide institutionalization recommendations grounded in SNA.

- Distinguish the functions, critical activities, and essential SNA information requirements.

4. Results

- Performance: EO has been studied mainly for its influence on business performance, considering three dimensions: individual, team, and organizational (Covin and Slevin 1988; Rauch and Frese 2008). Research shows that EO can improve the company’s ability to adapt, be proactive, and innovate, which are essential characteristics in a volatile and competitive environment. Studies by Anderson and Eshima (2013), as well as Saeed, Yousafzai, and Engelen et al. (2014), highlight the relevance of organizational structure in maximizing the impact of OE on performance. This is particularly important for micro-firms, which often operate with limited resources and more informal structures than large firms.

- Innovation: This is one of the fundamental dimensions of EO and is associated with a firm’s ability to generate new ideas, products, or services that enable it to adapt to changing market demands. Hult et al. (2004) and Rhee et al. (2010) suggest that, while EO focuses on entrepreneurial attitudes, innovativeness is directly related to result-oriented behavior, which is crucial for the success of microenterprises in disruptive contexts. In this sense, proactivity and initiative within EO foster the ability of microenterprises to take advantage of emerging opportunities and mitigate risks (Najar and Dhaouadi 2020; Shahzad et al. 2022).

- Market orientation: This has been studied from two main perspectives: exploration and exploitation. Exploration focuses on a thorough knowledge of the customer and the competition. According to Slater and Narver (1995), it is essential to collect and analyze detailed information on market needs and competitors’ activities to adjust business strategies effectively. Conversely, exploitation involves the generation, dissemination, and response to market information throughout the organization (Hervé et al. 2020; Caemmerer and Hynes 2022). This process is critical for strategic adaptation and reaction to market dynamics, emphasizing how information is used to make decisions that promote sustainable competitive advantages.

- Sustainability orientation: This emerges as a critical component in this effort, involving companies adopting practices and strategies that ensure their future, considering not only economic performance but also social and environmental impacts. There are different approaches to studying this relationship. For example, some authors conclude that EO is a precursor to sustainability orientation, and that companies will strengthen their strategic commitment to sustainability as they consolidate their entrepreneurial commitment (Lumpkin and Dess 1996; Wales et al. 2015). Other authors such as Rodriguez Cano et al. (2004), Lopes de Sousa Jabbour et al. (2020) and Rodrigues et al. (2021) see a convergence of two dimensions, where sustainability practices are integrated into business strategies, thus impacting business performance. Thus, the company gains relevance in social aspects such as corporate social responsibility (CSR) (Silva et al. 2021; Arend 2024), green innovation (Rodriguez Cano et al. 2004), environmentally friendly technologies (Raju et al. 2011), operational efficiency by reducing waste, and improvements in both economic and non-economic performance (Elkington 1997), which influences value creation.

5. A Conceptual Model Based on a Microenterprise

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbade, Eduardo Botti, Giana de Vargas Mores, and Caroline Pauletto Spanhol. 2014. The Impact of Entrepreneurial Orientation on Sustainable Performance: Evidence of Msmes from Rio Grande do Sul. Revista de Gestão Social e Ambienta 8: 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheampong, George, Mahama Braimah, Daniel M. Quaye, and Samuel Kwasi Buame. 2014. Impact of Demographic Factors on Technological Orientations of BOP Entrepreneurs in Ghana. International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management 11: 1450037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AEO. 2024. Small Business Facts. Washington, DC: AEO. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, Umair, Soleman Mozammel, and Fazluz Zaman. 2020. Impact of ecological innovation, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial orientation on environmental performance and energy efficiency. International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy 10: 289–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Awlaqi, Mohammed Ali, Ammar Mohamed Aamer, and Nasser Habtoor. 2021. The effect of entrepreneurship training on entrepreneurial orientation: Evidence from a regression discontinuity design on micro-sized businesses. The International Journal of Management Education 19: 100267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Brian S., and Yoshihiro Eshima. 2013. The influence of firm age and intangible resources on the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and firm growth among Japanese SMEs. Journal of Business Venturing 28: 413–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansoff, H. Igor, Daniel Kipley, Alfred O. Lewis, Roxanne Helm-Stevens, and Rick Ansoff. 2019. Implanting Strategic Management. Cham: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Apfel, Dorothee, and Carsten Herbes. 2021. What Drives Senegalese SMEs to Adopt Renewable Energy Technologies? Applying an Extended UTAUT2 Model to a Developing Economy. Sustainability 13: 9332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arend, Richard J. 2024. The Advantages of Entrepreneurial Holism: A Possible Path to Better and More Sustainable Performance. Administrative Sciences 14: 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astuti, Rifelly Dewi, Adi Zakaria Afiff, and Tengku Ezni Balqiah. 2017. Which SMEs has the B est Marketing Performance? Paper presented at the European Conference On Innovation and Entrepreneurship, Paris, France, September 21–22; pp. 68–77. [Google Scholar]

- Bala, Bilash Kanti, Fatimah Mohamed Arshad, and Kusairi Mohd Noh. 2017. Systems Thinking: System Dynamics. Singapore: Springer, pp. 15–35. [Google Scholar]

- Baldegger, Rico, Pascal Wild, and Patrick Schueffel. 2021. The Effects of Entrepreneurial Orientation in a Digital and International Setting. Leeds: Emerald Publishing Limited, pp. 145–74. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, Stafford. 1984. The viable system model: Its provenance, development, methodology and pathology. Journal of the Operational Research Society 35: 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, Stafford. 1985. Diagnosing the System for the Organization. London: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Borgatti, Stephen P., Ajay Mehra, Daniel J. Brass, and Giuseppe Labianca. 2009. Network Analysis in the Social Sciences. Science 323: 892–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgatti, Stephen P., Martin G. Everett, and Jeffrey C. Johnson. 2013. Analyzing Social Networks. London: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Bossmann, Ulrike, Beate Ditzen, and Jochen Schweitzer. 2016. Organizational stress and dilemma management in mid-level industrial executives: An exploratory study. Mental Health & Prevention 4: 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caemmerer, Barbara, and Niki Hynes. 2022. Antecedents and Consequences of Market Orientation in Micro Organisations: An Abstract. Cham: Springer, pp. 225–26. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso Castro, Pedro Pablo, and Angela Espinosa. 2019. Identification of organisational pathologies. Kybernetes 49: 285–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascio, Wayne F. 2019. Training trends: Macro, micro, and policy issues. Human Resource Management Review 29: 284–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, Abhirup. 2015. Organizational adaptation in an economic shock: The role of growth reconfiguration. Strategic Management Journal 36: 1717–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Yen-Chun, Po-Chien Li, and Kenneth R. Evans. 2012. Effects of interaction and entrepreneurial orientation on organizational performance: Insights into market driven and market driving. Industrial Marketing Management 41: 1019–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chienwattanasook, Krisada, and Kittisak Jermsittiparsert. 2019. Influence of entrepreneurial orientation and total quality management on organizational performance of pharmaceutical SMEs in Thailand with moderating role of organizational learning. Systematic Reviews in Pharmacy 10: 223–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, Jeffrey G., and Dennis P. Slevin. 1988. The influence of organization structure on the utility of an entrepreneurial top management style. Journal of Management Studies 25: 217–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabić, Marina, Nebojša Stojčić, Marijana Simić, Vojko Potocan, Marko Slavković, and Zlatko Nedelko. 2021. Intellectual agility and innovation in micro and small businesses: The mediating role of entrepreneurial leadership. Journal of Business Research 123: 683–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ruysscher, De Ruysscher Clara, Claes Claudia, Lee Tim, Fenming Cui, van Loon Jos, De Maeyer Jessica, and Schalock Robert. 2017. A Systems Approach to Social Entrepreneurship. Voluntas 28: 2530–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deslatte, Aaron, William L. Swann, and Richard C. Feiock. 2021. Performance, Satisfaction, or Loss Aversion? A Meso–Micro Assessment of Local Commitments to Sustainability Programs. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 31: 201–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis, Stefan. 2021. Social capital and entrepreneur resilience: Entrepreneur performance during violent protests in Togo. Strategic Management Journal 42: 1993–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, Naveen, Satish Kumar, Debmalya Mukherjee, Nitesh Pandey, and Weng Marc Lim. 2021. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research 133: 285–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dung, Luu Tien, and Huynh Thi Thuy Giang. 2022. The effect of international intrapreneurship on firm export performance with driving force of organizational factors. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 37: 2185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, John. 1997. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business. Oxford: Capstone. [Google Scholar]

- Elshourbagy, Heba M., and Hesham O. Dinana. 2018. The Effect of Entrepreneurial Market Orientation on Firm Performance. Paper presented at the 8th International Conference on Information Communication and Management, Singapore, July 17–19; New York: ACM, pp. 102–7. [Google Scholar]

- Engelen, Andreas, Harald Kube, Susanne Schmidt, and Tessa Christina Flatten. 2014. Entrepreneurial orientation in turbulent environments: The moderating role of absorptive capacity. Research Policy 43: 1353–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espejo, Raul, and Daniel Kuropatwa. 2011. Appreciating the complexity of organizational processes. Kybernetes 40: 454–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkas, Gergely. 2016. The Effects of Strategic Orientations and Perceived Environment on Firm Performance. Journal of Competitiveness 8: 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, Hermann, Christian Korunka, Manfred Lueger, and Josef Mugler. 2005. Entrepreneurial orientation and education in Austrian secondary schools. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 12: 259–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavetti, Giovanni. 2012. PERSPECTIVE—Toward a Behavioral Theory of Strategy. Organization Science 23: 267–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharajedaghi, Jamshid. 2011. Systems Thinking, Managing Chaos and Complexity. A Platform for Designing Business Architecture, 3rd ed. Cambridge, MA: Morgan Kaufmann. [Google Scholar]

- Gherhes, Cristian, Tim Vorley, and Chay Brooks. 2020. The “additional costs” of being peripheral: Developing a contextual understanding of micro-business growth constraints. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 28: 59–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurtoo, Anjula. 2009. Policy support for informal sector entrepreneurship: Micro-enterprises in India. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship 14: 181–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Hend, Abdelkader Ahmed, Rashed Alhaimer, and Marwa Abdelkader. 2021. Moderating role of gender in influencing enterprise performance in emerging economies: Evidence from Saudi Arabian SMEs sector. Problems and Perspectives in Management 19: 148–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervé, Annaële, Christophe Schmitt, and Rico Baldegger. 2020. Digitalization, Entrepreneurial Orientation; Internationalization of Micro-, Small-, and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Technology Innovation Management Review 10: 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildbrand, Sandra, and Shamim Bodhanya. 2015. Guidance on applying the viable system model. Kybernetes 44: 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hult, G. Tomas M., Robert F. Hurley, and Gary A. Knight. 2004. Innovativeness: Its antecedents and impact on business performance. Industrial Marketing Management 33: 429–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynes, Niki, and Barbara Caemmerer. 2017. The Market Orientation of Micro-Organizations: An Abstract. Cham: Springer, pp. 415–16. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, Kristin C., Karen M. Landay, Joshua R. Aaron, William C. McDowell, Louis D. Marino, and Patrick R. Geho. 2018. Entrepreneurial orientation (EO) and human resources outsourcing (HRO): A “HERO” combination for SME performance. Journal of Business Research 90: 134–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Michael. 2018. Strategic Environmental Assessment for Wetlands: Resilience Thinking. In The Wetland Book. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 2105–15. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Eijaz Ahmed, Mohammad Alamgir Hossain, Mohammed Abu Jahed, and Anna Lee Rowe. 2021. Poor resource capital of micro-entrepreneurs: The mediating role of entrepreneurial orientation. Management Research Review 44: 1366–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Junhee, Kibum Kwon, and Jeehyun Choi. 2024. Rethinking skill development in a VUCA world: Firm-specific skills developed through training and development in South Korea. Personnel Review 53: 657–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klammer, Adrian, Stefan Gueldenberg, Sascha Kraus, and Michele O’Dwyer. 2017. To change or not to change–antecedents and outcomes of strategic renewal in SMEs. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 13: 739–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolaczyk, Eric D., and Gábor Csárdi. 2014. Statistical Analysis of Network Data with R. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kusa, Rafał, Joanna Duda, and Marcin Suder. 2021. Explaining SME performance with fsQCA: The role of entrepreneurial orientation, entrepreneur motivation, and opportunity perception. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge 6: 234–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layton, Roger A., and Christine Domegan. 2021. The Next Normal for Marketing—The Dynamics of a Pandemic, Provisioning Systems, and the Changing Patterns of Daily Life. Australasian Marketing Journal 29: 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes de Sousa Jabbour, Ana Beatriz, Nelson Oly Ndubisi, and Bruno Michel Roman Pais Seles. 2020. Sustainable development in Asian manufacturing SMEs: Progress and directions. International Journal of Production Economics 225: 107567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G. Tom, and Gregory G. Dess. 1996. Clarifying the Entrepreneurial Orientation Construct and Linking It To Performance. Academy of Management Review 21: 135–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manninen, Anneli. 2021. Supporting innovation and growth of microenterprises in peripheral region. Paper presented at the European Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship, Online, September 16–17; pp. 1174–81. [Google Scholar]

- Mautner, Gerlinde. 2005. The Entrepreneurial University: A discursive profile of a higher education buzzword. Critical Discourse Studies 2: 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, Stefan, Christine Duller, and Manuel Königstorfer. 2022. How to Manage a Crisis: Entrepreneurial and Learning Orientation in Out-of-Court Reorganization. Journal of Small Business Strategy 32: 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengist, Wondimagegn, Teshome Soromessa, and Gudina Legese. 2020. Ecosystem services research in mountainous regions: A systematic literature review on current knowledge and research gaps. Science of The Total Environment 702: 134581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Danny. 1983. The Correlates of Entrepreneurship in Three Types of Firms. Management Science 29: 770–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin, Ainul Abdul, Hasliza Abdul Halim, and Noor Haslina Ahmad. 2015. Competitive Intelligence Among SMEs: Assessing the Role of Entrepreneurial Attitude Orientation on Innovation Performance. Cham: Springer, pp. 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mothibi, Nkosinathi Henry, Mmakgabo Justice Malebana, and Edward Malatse Rankhumise. 2024. Munificent Environment Factors Influencing Entrepreneurial Intention and Behaviour: The Moderating Role of Risk-Taking Propensity. Administrative Sciences 14: 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muangmee, Chaiyawit, Zdzisława Dacko-Pikiewicz, Nusanee Meekaewkunchorn, Nuttapon Kassakorn, and Bilal Khalid. 2021. Green Entrepreneurial Orientation and Green Innovation in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs). Social Sciences 10: 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad Auwal, Abdullahi, Zainalabidin Mohamed, Mad Nasir Shamsudin, Juwaidah Sharifuddin, and Fazlin Ali. 2020. External pressure influence on entrepreneurship performance of SMEs: A case study of Malaysian herbal industry. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship 32: 149–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najar, Tharwa, and Karima Dhaouadi. 2020. Chief Executive Officer’s traits and open innovation in small and medium enterprises: The mediating role of innovation climate. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 27: 607–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navakitkanok, Pornthep, Supavadee Aramvith, and Achara Chandrachai. 2020. Innovative Entrepreneurship Model for Agricultural Processing SMEs in Thailand’s Digital and Industries 4.0 Era. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal 26: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Nawi, Noorshella Che, Abdullah Al Mamun, Raja Rosnah Raja Daud, and Noorul Azwin Md Nasir. 2020. Strategic orientations and absorptive capacity on economic and environmental sustainability: A study among the batik small and medium enterprises in Malaysia. Sustainability 12: 8957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Ríos, Juan E., and Jacqueline Y. Sánchez-García. 2024. Determining the Factors to Improve Sustainable Performance in a Medium-Sized Organization. Sustainability 16: 6937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Ríos, Juan E., Jacqueline Y. Sánchez-García, and Adrian Ramirez-Nafarrate. 2023. Sustainable performance in tourism SMEs: A soft modeling approach. Journal of Modelling in Management 18: 1717–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Ríos, Juan E., Norman Aguilar-Gallegos, Jacqueline Y. Sánchez-García, and Pedro Pablo Cardoso-Castro. 2020. Systemic Design for Food Self-Sufficiency in Urban Areas. Sustainability 12: 7558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2023. OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook 2023. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Olorunshola, Damilola Temitope, and Temitayo Isaac Odeyemi. 2023. Virtue or vice? Public policies and Nigerian entrepreneurial venture performance. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 30: 100–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinton, Sarah, Ana Canhoto, Sebastian Molinillo, Rebecca Pera, and Tribikram Budhathoki. 2018. Conceptualising a digital orientation: Antecedents of supporting SME performance in the digital economy. Journal of Strategic Marketing 26: 427–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, P. S., Subhash C. Lonial, and Michael D. Crum. 2011. Market orientation in the context of SMEs: A conceptual framework. Journal of Business Research 64: 1320–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramoglou, Stratos, Stelios Zyglidopoulos, and Foteini Papadopoulou. 2023. Is There Opportunity Without Stakeholders? A Stakeholder Theory Critique and Development of Opportunity-Actualization. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 47: 113–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, Casper Claudi, and Erlend Nybakk. 2016. Growth drivers in low technology micro firms. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management 20: 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, Andreas, and Michael Frese. 2008. Entrepreneurial Orientation. In Handbook Utility Management. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 89–103. [Google Scholar]

- Rhee, Jaehoon, Taekyung Park, and Do Hyung Lee. 2010. Drivers of innovativeness and performance for innovative SMEs in South Korea: Mediation of learning orientation. Technovation 30: 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, Margarida, Mário Franco, Rui Silva, and Cidália Oliveira. 2021. Success Factors of SMEs: Empirical Study Guided by Dynamic Capabilities and Resources-Based View. Sustainability 13: 12301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez Cano, Cynthia, Francois A. Carrillat, and Fernando Jaramillo. 2004. A meta-analysis of the relationship between market orientation and business performance: Evidence from five continents. International Journal of Research in Marketing 21: 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-García, Leticia Elizabeth, Norman Aguilar-Gallegos, Oswaldo Morales-Matamoros, Isaías Badillo-Piña, and Ricardo Tejeida-Padilla. 2019. Urban tourism: A systems approach—State of the art. Tourism Review 74: 679–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruokonen, Mika, and Sami Saarenketo. 2009. The strategic orientations of rapidly internationalizing software companies. European Business Review 21: 17–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-García, J. Yvette, Juan E. Núñez-Ríos, and Carlos López-Hernández. 2020. Systemic complementarity, an integrative model of cooperation among small and medium-sized tourist enterprises in Mexico. International Journal of Business Innovation and Research 23: 354–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarreal, Emilina R., and Joan C. Reyes. 2019. Exploring the entrepreneurial and innovation orientation of central luzon entrepreneurs using the global entrepreneurship monitor data. DLSU Business and Economics Review 28: 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Satalkina, Liliya, Lukas Zenk, Kay Mühlmann, and Gerald Steiner. 2022. Beyond Simple: Entrepreneurship as a Driver for Societal Change. Cham: Springer, pp. 888–96. [Google Scholar]

- Sayal, Amber, and Saikat Banerjee. 2022. Factors influence performance of B2B SMEs of emerging economies: View of owner-manager. Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship 24: 112–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SBA (Small Business Administration). 2015. Am I a Small Business? Available online: https://www.sba.gov (accessed on 26 April 2015).

- SBA. 2024. Business Dynamics Statistics (BDS); Washington, DC: SBA.

- Schwaninger, Markus. 2015. Organizing for sustainability: A cybernetic concept for sustainable renewal. Kybernetes 44: 935–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheidgen, Katharina, Franziska Günzel-Jensen, and Simon L. Schmidt. 2024. Entrepreneurial Resourcefulness Throughout Crisis. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwaninger, Markus, and José Pérez Ríos. 2008. System dynamics and cybernetics: A synergetic pair. System Dynamics Review 24: 145–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seet, Pi-Shen, Noel Lindsay, and Fredric Kropp. 2021. Understanding early-stage firm performance: The explanatory role of individual and firm level factors. International Journal of Manpower 42: 260–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selsky, John W., and Joseph E. McCann. 2012. Managing Disruptive Change and Turbulence through Continuous Change Thinking and Scenarios. In Business Planning for Turbulent Times: Methods for Applying Scenarios, 2nd ed. Edited by Rafael Ramirez, John W. Selsky and Kees Van der Heijden. New York: Routledge, pp. 167–86. [Google Scholar]

- Shaher, Adel Th Q, and Khairul Anuar Mohd Ali. 2020. The effect of entrepreneurial orientation on innovation performance: The mediation role of learning orientation on Kuwait SMEs. Management Science Letters 10: 3811–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, Khuram, Marco De Sisto, Muhammad Athar Rasheed, Sami U. Bajwa, Wei Liu, and Timothy Bartram. 2022. A sequential relationship between entrepreneurial orientation, human resource management practices, collective organisational engagement and innovation performance of small and medium enterprises. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship 40: 875–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Zhe, Ling Yuan, and Soo Hee Lee. 2022. Dynamic capabilities and entrepreneurial performance of Chinese start-ups: The mediating roles of managerial attitude towards risk and entrepreneurial behaviour. Asia Pacific Business Review 28: 354–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, Graça Miranda, Paulo J. Gomes, Helena Carvalho, and Vera Geraldes. 2021. Sustainable development in small and medium enterprises: The role of entrepreneurial orientation in supply chain management. Business Strategy and the Environment 30: 3804–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Ajay, Shashi Singh, and Kiran Singh. 2014. Engineering education and entrepreneurial attitudes among students: Ascertaining the efficacy of the indian educational system. Prabandhan: Indian Journal of Management 7: 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Slater, Stanley F., and John C. Narver. 1995. Market Orientation and the Learning Organization. Journal of Marketing 59: 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumiati, Sumiati. 2020. Integrating entrepreneurial intensity and adaptive strategic planning in enhancing innovation and business performance in Indonesian SMEs. Management Science Letters 10: 3941–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajeddini, Kayhan, Ulf Elg, and Myfanwy Trueman. 2013. Efficiency and effectiveness of small retailers: The role of customer and entrepreneurial orientation. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 20: 453–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleb, Nassim Nicholas. 2007. The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Talebi, Kambeiz, Arash Rezazadeh, and Amer Dehghan Najmabadi. 2015. SME alliance performance: The impacts of alliance entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial orientation, and intellectual capital. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business 24: 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wales, William, Johan Wiklund, and Alexander McKelvie. 2015. What about new entry? Examining the theorized role of new entry in the entrepreneurial orientation–performance relationship. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship 33: 351–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Xin, Zhe Zhang, and Ming Jia. 2024. Taming the black swan: CEO with military experience and organizational resilience. Asia Pacific Journal of Management. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, Radha, and Dharmendra Kumar. 2022. Linking non-financial motivators of women entrepreneurs with entrepreneurial satisfaction: A cluster analysis. World Review of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development 18: 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Song, Franziska B. Keller, and Lu Zheng. 2017. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Examples. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Ta-Kai, and Min-Ren Yan. 2019. Exploring the Enablers of Strategic Orientation for Technology-Driven Business Innovation Ecosystems. Sustainability 11: 5779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, Halil, and Serhat Saygin. 2011. Effects of owners’ leadership style on manufacturing family firms’ entrepreneurial orientation in the emerging economies: An emprical investigation in Turkey. European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences 32: 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, Sung-Joon, Hag-Min Kim, and Yea-Rim Lee. 2019. The effects of international entrepreneurial orientation and entrepreneurial activities on SMEs’ export performance. Journal of Korea Trade 23: 156–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Man, Saonee Sarker, and Suprateek Sarker. 2013. Drivers and export performance impacts of IT capability in ‘born-global’ firms: A cross-national study. Information Systems Journal 23: 419–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zokaei, Keivan. 2011. How Systems Thinking Provides a Framework for Change: A Case Study of Disabled Facilities Grant Service in Neath Port Talbot County Borough Council. In Systems Thinking: From Heresy to Practice. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 17–39. [Google Scholar]

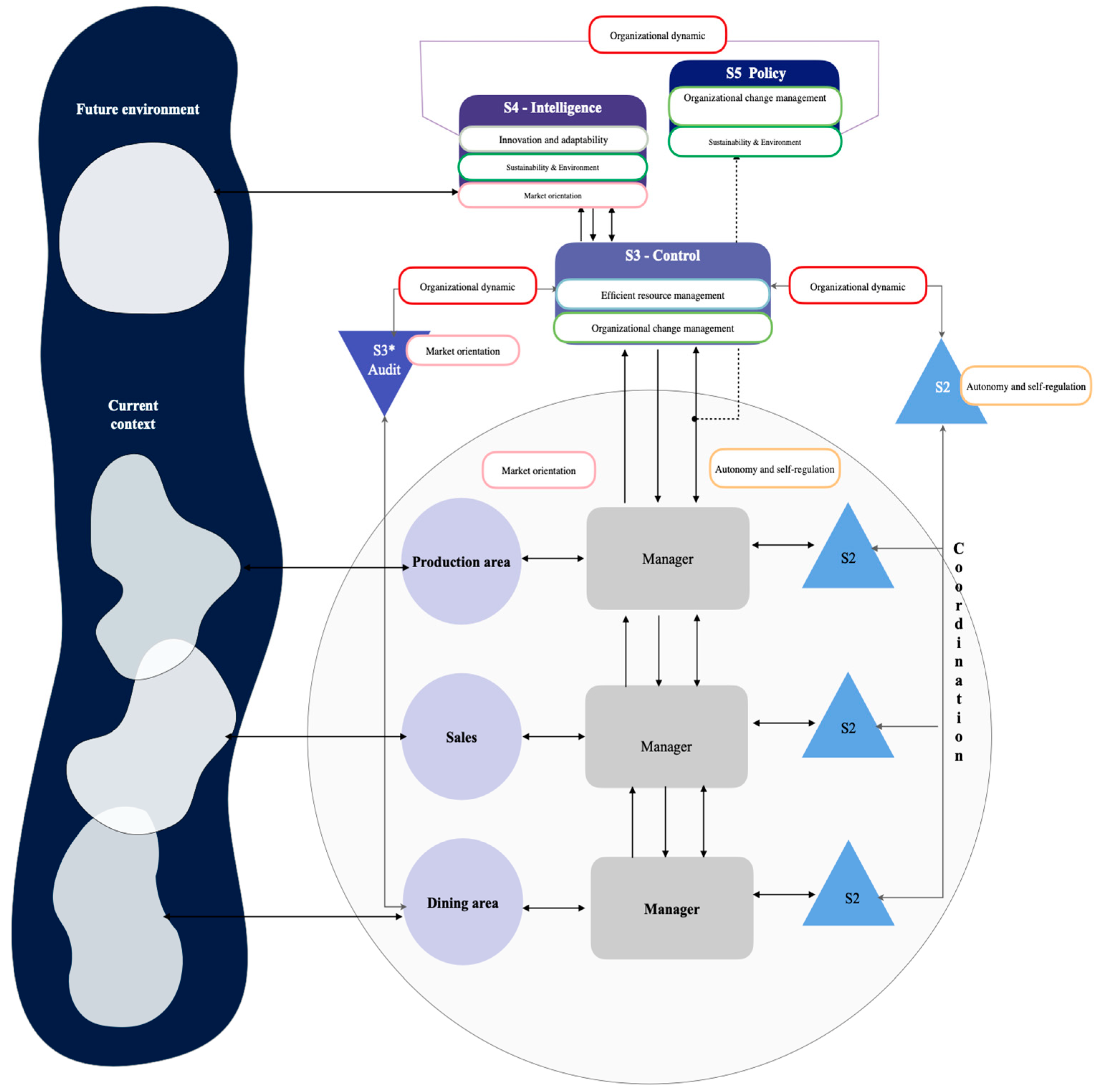

| Function | Objective |

|---|---|

| S1 | This subsystem supervises the daily operational activities and essential tasks for the functioning of the organization. As the first line of the organization, it focuses on the basic functions of production and customer service. |

| S2 | This subsystem focuses on coordination, enabling communication throughout the organization and ensuring the effective flow of information between operational and administrative departments. The greatest strength of S2 is the synchronization, conflict resolution, and culture of collaboration it brings to members and various departments. |

| S3 | Subsystem 3 focuses on the control and supervision of the performance of S1, ensuring alignment between operations and the organization’s standards and objectives. It encompasses goal setting, performance metric analysis, and a proactive approach to corrective actions for a stable and effective system. S3* |

| S4 | The fourth subsystem is intelligence, responsible for collecting, evaluating, and disseminating relevant information for the organization. It is imperative that S4 monitor the external environment for threats and opportunities while gathering internal data for informed decision-making, ensuring a smooth adaptation to strategic changes. |

| S5 | Subsystem 5 manages organizational policy, setting the overall direction, objectives, and strategy. It is responsible for defining policies, allocating resources, and carrying out long-term strategic planning while establishing the framework followed by the remaining subsystems to ensure that broader objectives are met. |

| Label | Nodes | Description |

|---|---|---|

Innovation and adaptability | 47 | This community emphasizes innovation and adaptation in supervisory roles within dynamic contexts—focusing on identifying strategic factors in business operations and making necessary adjustments in response to emerging trends (Kusa et al. 2021). Successful adaptations require business leadership that promotes rapid responses to changing circumstances through entrepreneurial intensity, which is based on focusing and acting around emerging opportunities (Sumiati 2020). Meeting increased demand requires efficient resource management, including the proper allocation of available resources. When the necessary resources are not available, human resource outsourcing can be used to acquire the necessary skills (Irwin et al. 2018). Successful adaptations entail an entrepreneurial leadership that encourages quick responses to changing circumstances via an entrepreneurial intensity resting on focus and action surrounding arising opportunities. An increase in demand calls for proper resource management (Shahzad et al. 2022) with the efficient and effective allocation of resources, and when unavailable, human resource outsourcing can acquire the desired skills. Strategic modifications are executed via a responsive market that facilitates competitive advantages. The decision involves risk-taking (Mothibi et al. 2024) in the forms of strategic marketing (Quinton et al. 2018), information communication technology (Baldegger et al. 2021), and alliance formation (Talebi et al. 2015). |

Autonomy and self-regulation | 34 | This community focuses on the challenges faced by organizations and how exploration activities lead to consequences (Seet et al. 2021), from which decisions for strategic renewal (Klammer et al. 2017) promote the idea that the components of an organization must have the capacity to operate independently; however, it is always aligned with the goals and needs of the organization. In the organizational self-regulation of SMEs, several fundamental factors arise: an orientation toward the Internet for the development of marketing tools for sustained competitiveness; financial literacy for informed decision-making and improving the likelihood of access to financing; and product innovation to develop and introduce innovative products in line with social entrepreneurship initiatives (De Ruysscher et al. 2017) to address current challenges. |

Sustainability and environment | 23 | The works linked in this group integrate ethical and sustainable principles into the innovation process with efforts to advance and instill the sustainable development (Silva et al. 2021) of ecological innovation and efficiency (Ahmed et al. 2020) to meet the present needs without compromising future generations. Working in conjunction, an innovation ecosystem (Yang and Yan 2019) generates a positive reinforcement effect between innovative activities and the market through collaboration, knowledge sharing, and ethical considerations. In return, green EO positively influences economic performance (Muangmee et al. 2021), evolving into sustainable business practices (Lopes de Sousa Jabbour et al. 2020) that consider their environmental and societal impacts. Such sustainable achievements are facilitated by instrumental contributions from visionary leadership (Dung and Giang 2022), ensuring operating principles, such as total quality management (Chienwattanasook and Jermsittiparsert 2019), align and satisfy proposed sustainability targets. |

Market orientation | 27 | The KWs in this group cover factors that foster systematic innovation through open-minded perspectives and awareness of the peripheral region (Manninen 2021), where market encroachment or expansion is initially observed. To gain competitive intelligence (Mohsin et al. 2015), information internationalization (Yoo et al. 2019) is utilized to expand systems and technologies when adapting to diverse marketplaces and their environments while simultaneously being exposed to tolerable levels of managerial risk (Shi et al. 2022) in decision-making. Results from this diversification are reflected through the development of a market and technology innovation orientation (Sarreal and Reyes 2019), which works along a growth orientation (Sayal and Banerjee 2022) that prioritizes expansion and development through the incorporation of disruptive factors, such as digital entrepreneurship (Hervé et al. 2020) and other development programs (Abbade et al. 2014). |

Organizational dynamic | 38 | Effective interaction between the parts of the enterprise is crucial. Exchange and interaction between the parts of the organization must be ensured through effective collaboration and communication that contribute to the viability of the enterprise. This KW series brings together publications focusing on the complex and changing patterns of social interactions, connections, and authority within an organization. An empowering organizational culture (Gurtoo 2009), along with an effective leadership style made up of industry knowledge (Navakitkanok et al. 2020) and insider perspectives (Dabić et al. 2021), can guide an organization through the development of a long-term orientation (Shaher and Ali 2020). Embedded in the culture are power and influence (Olorunshola and Odeyemi 2023) that foster a comfortable working environment that takes into consideration empathy and individual team member roles (Ramoglou et al. 2023). In return, high employee engagement (Frank et al. 2005; Yadav and Kumar 2022) nurtures motivation, enabling performance-increasing entrepreneurial behavior (Kusa et al. 2021). |

Organizational change management | 32 | New initiatives at different organizational levels support the promotion of employee autonomy to solve problems or improve processes without waiting for instructions. The nodes in this cluster relate to an organizational culture (Deslatte et al. 2021) open to transformational leadership (Yildirim and Saygin 2011) through an active awareness of the general external environment (Elshourbagy and Dinana 2018) and the effects of its public policies (Olorunshola and Odeyemi 2023) on the business ecosystem. Part of addressing ongoing changes is the evolution from a loss-averse mindset to a risk–reward approach (Deslatte et al. 2021), encouraging a strong innovation orientation (Nawi et al. 2020) and embracing technology acceptance (Acheampong et al. 2014) and its critical role in developing a sustainable strategic orientation (Muhammad Auwal et al. 2020). The effects encompass a customer orientation (Tajeddini et al. 2013; Rasmussen and Nybakk 2016) that integrates business marketing dimensions (Astuti et al. 2017), including customer relationship management systems (Hynes and Caemmerer 2017). |

Efficient resource management | 43 | The publications in this area relate to critical success factors (Hassan et al. 2021) that must be identified and adapted as needed by organizations. Strategic management theories, including the resource-based view of the firm (Zhang et al. 2013; Khan et al. 2021), consider available internal resources and capabilities when adjusting to a changing landscape. When faced with scarce resources, organizations must invest in proper entrepreneurship training (Al-Awlaqi et al. 2021), including technical courses (Singh et al. 2014) and competencies (Satalkina et al. 2022) that bring out and develop the individual EO (Apfel and Herbes 2021). Gained insights shape the behaviors and structures of markets through marketization (Mautner 2005) and a digital orientation (Quinton et al. 2018; Navakitkanok et al. 2020) to align strategies and practices with disruptive technologies. Through this process, a learning orientation triggers a reorganization (Farkas 2016; Navakitkanok et al. 2020; Mayr et al. 2022), promoting continuous learning and improvements in organizational behavior (Baldegger et al. 2021). |

| System | EO Fact | Performed by | Functional Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| System 1 Operation  | Autonomy and self-regulation | Production area | Quality control: meeting or exceeding labor expectations (raw material inspections, proper storage practices, hygiene standards, proper cooking procedures, portion controls, temperature monitoring, allergen controls) Efficiency: ensuring resources are utilized competently, minimizing waste, and maximizing output (standardized recipes and processes, prep work optimization, kitchen layout design, equipment utilization, batch cooking, cross-training staff, time management) Continuous improvement: providing feedback and metrics to enhance operations (employee engagement and development, process innovations, waste reduction, energy conservation, tech integration) Safety compliance: ensuring health and well-being of consumers and staff (hazard analysis and critical control points, sanitation procedures, allergen management, pest control, storage practices, safe equipment use, labeling and traceability) |

| Service and dining area | Service excellence: friendly, attentive, and personalized (warm greetings, accommodating needs and preferences) Product knowledge: well versed in offerings, cooking methods, and allergen information (menu-ingredient knowledge, preparation methods, specialty and signature items, nutritional information, new product introductions, food pairing recommendations) Communication skills: clear and courteous words (positive language, active listening, empathy, emotional intelligence, verbal and nonverbal skills, conflict resolution, customer recovery, telephone and written, team dynamics and cross-cultural communication) Problem resolution: handling complaints and dissatisfaction (de-escalate, empathize, offer solutions, resolve) Table management: server etiquette and meeting consumer needs without intrusiveness (reservation handling, seating assignments, guest recognition, waitlist management, host and server communication, table tracking systems, upselling opportunities, conflict resolution, experience enhancement) Attention to detail: accurate order-taking, attractive presentation, prompt service (completeness and accuracy check, hygiene and sanitation practices, allergens and dietary restrictions, quality control checks, customer interactions, inventory management, equipment maintenance) Empathy and cultural sensitivity: empathy training (diverse dietary requirements, customs, and communication; implicit bias; active listening; personal boundaries; intercultural language and communication) Cleanliness and Ambience: upholding standards in dining, restrooms, and customer service areas (sanitation procedures, cleaning schedules, food contact surfaces, pest control, waste management, emergency clean-up procedures, regular inspections and feedback) | ||

| Market orientation | Sales | Upselling and Cross-selling: enhancing customer experience and expanding their preferences (understanding needs, recommendations, add-ons and upgrades, highlighting value propositions, complimentary alternatives and substitutions, loyalty programs, gift cards, positive phrasing, suggestive and descriptive language, incentives and rewards) Customer relationships: connecting with consumers via personalization for a loyal base (understanding customer needs, empathetic communication, trust establishment, conflict resolution and de-escalation, service mindset, personalized service, customer feedback and reviews, customer retention) | |

| System 2 Coordination  | Autonomy and self-regulation | Supervisor | Efficiency: save time and resources (insider techniques, continuous learning and development, online training modules and simulations, cross-training, standardized training materials) Quality control: employees receive accurate, consistent learning, resulting in effective performance (customer satisfaction, real-time feedback and skills assessments, training programs, observation-coaching, documentation and record-keeping) Cost management: ensure effective use of raw materials and time (internal resources, cross-training, portion control) Safety and compliance: informing and ensuring employee welfare (food safety training, personal protective equipment, emergency response, chemical handling, accident prevention, refresher training) Environmental: striving to reduce carbon footprint by adopting eco-friendly practices (recycling and waste reduction, energy and water conservation, cleaning and disposal practices) Menu knowledge: effective consumer communication (ingredient and preparation process expertise; portion size and plating; taste and flavor profiles; food and beverage pairing; seasonal dish, specials, and signature dish proficiency; cross-selling and upselling techniques; mock service and role-playing) Equipment operation/maintenance: safe and efficient use of appliances and instruments (familiarization, safety procedures, operating instructions, cleaning/sanitating/maintenance schedule, troubleshooting, preventive maintenance, knife handling/sharpening, regulatory compliance standards) Customer service: excellent service creates positive guest experiences (greeting patrons, effective communication, personalized service, handling customer suggestions-complaints, tableside manners, menu knowledge, time management, health and safety protocols, follow-up and thank you) Cultural sensitivity and inclusion: respectful and considerate of diverse cultures, backgrounds, and identities (diversity training, bias awareness, language and communication training, religious observances, disability awareness and accessibility, conflict resolution) Emergency response: employee and guest safety in situation emergencies (fire safety, first aid, evacuation procedures, emergency evacuation, chemical and hazardous materials, power outage, active shooter, documentation and record-keeping) |

| System 3 Control  | Organizational change management | Chef | Policy: enforcing company policies and procedures related to food safety, hygiene standards, and operational protocols Workflow mapping: staff scheduling, task assignments, and workflow management (employee performance, feedback, resolution of arising issues) Emergency response: implementation of procedures to coordinate evacuation and ensure safety (fires, medical, security incidents) Conflict resolution: self-regulation of staff to maintain harmonious work environment to uphold business reputation |

| Efficient resource management | Stress management: to improve integration and decision-making under pressure (stress management, deep breathing exercises, calm and focused during busy periods) Inventory management: inventory levels and controlling food costs (monitoring, placing orders, procedures to minimize waste, prevent shortages, overstocking) Quality assurance: enforcing quality standards for food preparation, presentation, and service (regular inspections and compliance audits, company standards) Product testing and sampling: to ensure that established standards and expectations are met (assess quality, consistency, and taste of offerings) | ||

| System 3* Audit | Autonomy and self-regulation | Chef and Supervisor | Food safety monitoring: regular inspections of food handling (temperature control, storage, preparation, HACCP and FDA guidelines) Sanitation and hygiene compliance (health regulations, equipment cleanliness, utensils, food preparation areas, personal hygiene practices) Allergen management: item labels to prevent cross-contamination (peanuts, dairy, gluten, shellfish) |

| System 4 Intelligence  | Market orientation | Chef and CEO—Manager | Forecasting and demand planning: to minimize waste, reduce stockouts, and meet customer demands (historical data, predictive analytics, seasonal trends, inventory optimization) Menu optimization: data analysis to maximize profitability and customer satisfaction (menu optimization, pricing strategies, promotional activities, bestselling items, underperforming dishes, menu innovation, profit maximization) Customer personalization: segmenting customers to reach target audiences and drive customer loyalty (demographics, purchasing behavior, preferences, promotions, menu recommendations) Supply chain management: to help businesses optimize operations (supplier performance, procurement costs, supplier term negotiations, inventory levels, lead times, risk mitigation) Operational efficiency: to identify process inefficiencies, staffing, and resource allocation (streamline operations, cost reduction, productivity enhancement) |

| Innovation and adaptability | CEO—Manager | Data collection and integration: obtaining data from various sources to create a comprehensive business view (point of sale, customer relationship management, inventory management, online reviews) Data analysis and reporting: to inform strategic decisions (trends, patterns, insights, reports, dashboard visualization) Performance monitoring: key performance indicators to identify improvement areas and track business goals progress (sales, revenue, profit margins, inventory levels) Compliance and risk management: risk identification, compliance tracking methods, corrective action, implementation, and liability mitigation Strategic planning and decision-making: to enable executives to make informed decisions based on data-driven insights (strategic planning initiatives, expansion opportunities, investment decisions) | |

| System 5 Policy  | Organizational dynamic/ Organizational change management | Strategic direction: review of mission, vision, long-term objectives, and formulation of organizational strategies Leadership: making decisions that impact the direction, growth, and success of the organization Financial management: ensuring sustainability and profitability through financial planning, budgeting, and resource allocation Business development: identifying opportunities for growth and expansion into new markets and partnerships Operational Oversight: monitoring and evaluating departmental and functional area performance Quality assurance: establishing and maintaining standards for continuous improvement and customer satisfaction Human resource management: attracting, retaining, and developing talented employees through recruitment, training, and performance management Risk management: identifying and mitigating operational, reputational, and financial risks | |

| Sustainability and environment | CEO—Manager | Stakeholder relations: creating and maintaining networks to build trust and organizational support Regulatory compliance: compliance with laws, regulations, food safety standards, and labor practices Learning culture: fostering a culture of continuous learning and responsiveness to market dynamics Corporate social responsibility: commitment to social and environmental leadership through sustainable practices and community engagement |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Suarez Ambriz, D.; Sánchez-Garcia, J.Y.; Núñez-Ríos, J.E. An Organizational Framework for Microenterprises to Face Exogenous Shocks: A Viable System Approach. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 315. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14120315

Suarez Ambriz D, Sánchez-Garcia JY, Núñez-Ríos JE. An Organizational Framework for Microenterprises to Face Exogenous Shocks: A Viable System Approach. Administrative Sciences. 2024; 14(12):315. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14120315

Chicago/Turabian StyleSuarez Ambriz, Denny, Jacqueline Y. Sánchez-Garcia, and Juan E. Núñez-Ríos. 2024. "An Organizational Framework for Microenterprises to Face Exogenous Shocks: A Viable System Approach" Administrative Sciences 14, no. 12: 315. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14120315

APA StyleSuarez Ambriz, D., Sánchez-Garcia, J. Y., & Núñez-Ríos, J. E. (2024). An Organizational Framework for Microenterprises to Face Exogenous Shocks: A Viable System Approach. Administrative Sciences, 14(12), 315. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14120315