1. Introduction

The corporate world has witnessed many scandals that have emerged due to misconduct in management or discreditable behavior by those in the C-suite. The ivory tower is no exception.

Mintz (

2022) cites scandals in several universities that experienced major financial costs. It was stated that at least USD 237 million at Penn State, USD 490 million at the University of Michigan, USD 500 million at Michigan State, USD 700 million at UCLA, and USD 852 million at USC were lost due to financial scandals. Of course, one cannot ignore the invisible costs (campus morale, reputation loss for academics and staff, bad press, etc.), which are just as important as the financial costs, and perhaps more damaging. The most recent US Gallup poll (see

Blake 2023) found that only 36 percent of Americans have “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in higher education, which is down by about 20 percent from the last eight years. The contributory factors for the increase in mistrust in higher education are attributable to the fact that it is increasingly difficult for the public sector to provide a level of funding to higher education sufficient to keep the system internationally competitive (

Weber and Bergen 2006, p. 7).

The challenges facing the higher education sector and the loss of trust in this sector have brought to light the issues of leadership roles and positions, and the lack of gender balance in the ivory tower. Some researchers (

Morley 2013;

Currie et al. 2002) call this environment “greedy work” due to the long working hours and lesser control over when the hours are worked. Cyprus was selected as the country to investigate the above topic because it is a country where HTIs had a “veritable boom in the last five years” (

Polykarpou 2022). However, despite efforts by the government to develop the sector, the country is ranked last in the latest

She Figures (

2021) with the worst Glass Ceiling Index on the issue of gender leadership in academia of the member states. Cypriots, traditionally placed a strong emphasis on education. The country is a member state of the European Union, with the second-highest higher education degree holders. Furthermore, a greater proportion of women (64.4%) are higher degree holders compared to men (49.2%) (

Polykarpou 2022).

Gender Equality is one of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (i.e., Goal 5) of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (

United Nations 2015) adopted by world leaders in 2015. Gender equality is also highlighted in the Gender Equality Strategy 2020-2025 which emphasizes that inclusive and diverse leadership is needed to bring forward new ideas and innovative approaches that better serve EU society (

European Commission 2020a). At the same time the European Commission has found that the under-representation of women in senior academic and decision-making positions in the EU is a significant issue hindering the growth of the European Research Area (ERA) (

European Commission 2020b). Women in leadership roles in HTIs are important for three reasons. Firstly, universities are called upon to become strategic actors and evolve from their traditional “top-down controlling position toward a more supportive and enabling function” (

Pruvot et al. 2023, p. 91). These traits of being less domineering and more supportive are feminine skills. Secondly, universities improve the quality of life of individuals and collective life as they are a breeding place for shaping future generations, and, thirdly, governments allocate millions of dollars annually to the public budgets of HTIs. Thus, those holding leadership positions in HTIs must have high ethical, moral fiber. However, when students at universities experience women academics holding lower ranking positions who do not take up leadership positions, this situation is normalized for them, and they expect that this is how society functions. Therefore, it follows that the stereotype that males are leaders will be mirrored in politics, business, and the executive.

Generally, to rise to leadership positions in HTIs, one needs to have tenure, i.e., be at the rank of full professor.

Maranto and Griffin (

2011) argue that the professoriate is a highly gendered occupation due to the tenure clock, child-bearing years, and caregiver responsibilities, which make it inhospitable for women to publish as much as their male counterparts and or undertake administrative roles. As illustrated by

Times Higher Education (

2024), women have been rising to leadership positions in the academia in Western universities; however there are many universities around the globe where leadership posts in academia are extremely gendered. In the same article (

Times Higher Education (

2024), in March 2024, a quarter of the top universities around the globe were headed by women, an increase of 82% in the last nine years. These universities are based in the United Kingdom, United States of America, Australia, Germany, Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, Finland, Italy, Hong Kong, and New Zealand. There are other countries; however, with minimal to no women holding top positions in universities.

Jones (

2024) found that, in the UK, while “women make up 54 percent of the higher education workforce and occupy 45 percent of academic positions, only 28 percent of academic leaders are women…The proportion of male staff on senior higher education contracts is nearly three times higher than for female staff. Of the vice-chancellors, 83 percent identify as male”. This ambiguity breeds further inequality, and as a result, students studying in such extremely gendered universities take it as a status quo.

To address the gender imbalance in leadership positions in academia, the paper investigates: (a) whether the HTIs are considered to be an extremely gendered organizational environment, (b) if women in HTIs have the leadership skills their male counterparts possess, and (c) what holds women back from applying for leadership positions in HTIs?

Our results have relevance at the micro level (i.e., for the institutions and people within) as well as at the macro level (for the sector and wider society). Utilizing the methodology developed by other researchers, the authors have established that HTIs have the characteristics of an extremely gendered organizational environment. This suggests that authorities, legislators, and regulators in the education sector, need to take steps to implement institutional changes to rectify the situation and smoothen the gender imbalance in HTIs. The importance of the second finding relates to the gender stereotypes which create biases in leadership perceptions. More specifically, the authors have found that while women academics possess some of the skills expected to be possessed by those holding leadership roles in academia, women possess different skills and traits to their male counterparts. Therefore, this finding provides the basis for the argument that by having gender balance in leadership positions in HTIs, all the skills and traits expected of academic leaders will be holistically covered by both genders. The third finding has established that women are held back from applying for leadership roles in their HTI due to: (a) family obligations, (b) lack of collegial support, (c) self-exclusion from leadership roles due to the boys-room alliance, (d) identity and gender-based barriers which create stereotypes and biases all adding to credence for the Glass Ceiling Index Gap as well as the vertical segregation (

She Figures 2021).Therefore, this paper has established, for the first time, that HTIs are extremely gendered organizations. Unlike other research, this paper lays the foundational contention that women academics are not leaders, not because they do not possess the skills and traits expected of academic leaders, but because they do not possess the skills and traits of a stereotypical academic leader (i.e., a male). Finally, gender- and stereotype-based biases have been found, thus reinforcing and adding credence to the glass ceiling phenomenon. Therefore, by mapping the reasons behind the vertical segregation, the authors are in a better position to lay out policy recommendations to address the gender imbalance.

2. Literature Review

While women constitute a substantial proportion of the labor force, they are under-represented in top leadership positions (

Tuniy et al. 2023). Utilizing the upper echelons (

Hambrick and Mason 1984) and social role (

Eagly 1987) theories,

Kirsch (

2018) found that women possess different values from men, as women tend to be more compassionate, inclusive, and ethical in their decision-making. This finding is also supported by

Tuniy et al. (

2023), who found that women in top leadership positions have a more ethical orientation towards their employees than their male counterparts. Thus, they recommend that having gender balance and representation in corporate boards will result in positive outcomes for firms and society without compromising productivity. With that finding in mind, the current authors will investigate whether leadership in higher tertiary institutions (HTIs) is gender balanced, and if not, why not.

Katuna (

2019, p. 19), in her degendering leadership work summarizes the characteristics of effective leadership in academia. These characteristics incorporate “communality, shared governance, teamwork and proper rewards and acknowledgment for exceptional performance”. In addition, she mentions that leaders in academia need to value diversity, and leaders ought to have “a strong ego, not a big ego that incorporates sincere care for the institution” (

Katuna 2019, p. 20). Academics who aim to gain positions as deans, heads of department, members of university senates or university councils, or even become rectors (chancellors) or vice-rectors (vice-chancellors) ought to be able to understand and navigate toward change by acknowledging that his/her opinions and views may be different to the needs of the stakeholders, but be able to balance his/her views with those of others if he/she has to put his/her needs and ambitions after the needs of the institution (

Katuna 2019, p. 39) by leaving their egos behind. Katuna also highlights that “successful leaders demonstrate respect for their position, their predecessors, and future successors”), are good listeners and facilitate options for the communicator by being humble.

Katuna (

2019) notes that women are not well versed with teamwork and shared governance, but at the same time, notes that women can embody a selfless understanding and facilitate credit-sharing abilities, which illustrate teamwork abilities.

Dinh et al. (

2021, p. 996) have found that “academic staff and leaders perceive the notion of leadership in balanced contexts as a complex concept.” The same authors cite the work of

Bryman (

2007) and

Hoppe and Speck (

2003), who found that an academic leader needs to possess the following competencies: “honesty, integrity, credibility, fairness, a high level of energy, strong goal orientation, perseverance, excellent communication skills, and objective decision”, (

Dinh et al. 2021, p. 999), “team management skills, being able to gather people when stressed, have empathy, research credibility and reputation, as well as institutional reputation enhancement” (

Dinh et al. 2021, p. 1005). The same authors have advocated that for an academic to be “motivated” to become an academic leader, one needs to consider both the intrinsic values (personal growth, sense of responsibility, and authority) as well as the extrinsic ones (rewards, recognition, status, achieving more power, opportunity, and resources). It should be noted, however, that

Dinh et al. (

2021) failed to consider gender differences regarding motivators.

Women may need other motivators to encourage them to express their wish to become leaders due to stereotypes and androgenic working environments, as well as the challenges they encounter at work and in their private lives.

Hyatt (

2022) found that once an academic attains a tenure track (i.e., professoriate level in Cyprus), there is increased stress, burnout, and higher workloads due to increased administrative roles and research publication expectations which lead to emotional exhaustion (

Myry et al. 2020).

Watts and Robertson (

2011, p. 45) have found that women reported higher emotional exhaustion scores because they: juggle multiple roles at work and home, depleting their emotional reserves, work harder than men to maintain an empathic manner (

Bilge 2006), and are more likely than men to admit to distress or anxiety. Both

Mandrekar (

2023) and

Cochran (

2023) have found that women are more likely than men to leave their place of employment when they experience stress or burnout at work.

Mandrekar (

2023) also found that the drivers of burnout faced by women are: the juggling of their primary caregiver role, household manager responsibilities, and successful professional expectations.

Sullivan et al. (

2023) have reported that the burnout challenge women face has an impact on leadership inequality. The current paper will investigate the challenges and barriers women face in considering taking up leadership positions in HTIs.

As illustrated earlier, the leadership of three-quarters of the top universities, and, perhaps, a higher proportion of the rest of the universities globally, are androgenic.

Bryan et al. (

2021, p. 940) explain that in “extremely gendered” organizations, a gendered substructure maintains ‘masculine dominance’. Hence, this situation relegates women to a position of “peripheral inclusion in leadership roles”. Furthermore, organizations where the leadership role is held predominately by males, demonstrate a masculinity-conferring organization that excludes women from key leadership roles while superficially accepting women into roles that do not challenge the hierarchy and give a rapper stamp to the hegemonic masculinity. Some extremely gendered organizations already studied are sports organizations (

Bryan et al. 2021), the military (

Sasson-Levy 2011), and fire service (

Tyler et al. 2019).

Bryan et al. (

2021) explain that organizations that can be considered “extremely gendered” possess the following characteristics:

In the current study, the first research question to be investigated is to determine whether HTIs are extremely gendered based on the above characteristics.

As

Blackmore (

2017) argues, the authority to be a leader in academia has traditionally been seen to be legitimately unproblematic by a male. The same author argues that one needs to reconstruct the concept of leadership and consider the female part of this equation. In this, where one needs to hold a tenure position to be considered for a leadership position, males resist moving the needle (i.e., changing a situation to a noticeable degree) and do not promote women by encouraging top-down control. Not having women in committees and the Rectorate (Rector or Vice Rector) means that the ideas held by the males are not questioned. Such practice legitimizes the “problematic practices and processes and puts women at risk of harm” (

Bryan et al. 2021, p. 945).

Blackmore (

2017, p. 68) argues that many women, who have the qualifications and aptitude, prefer more democratic styles of organization and do not apply for leadership roles in education. The same author advocates that women tend not to have the aspiration, nor do they have the leadership skills displayed by their male counterparts. Blackmore found that, historically, leadership traits are those predominately held by males (e.g., aggressive, forceful, competitive, independent behavior). Women are expected, culturally, to display traits of ‘femininity’, being emotional, passive, dependent, nurturing, intuitive or submissive. Consequently, “women are perceived to be poor leaders”, which is a myth. In recent years,

Pang et al. (

2023) acknowledged that successful leaders are those who possess feminine characteristics of caring, empathy, and compassion. Thus, the view that women do not fit the leadership characteristics is yet another myth.

Blackmore (

2017, p. 123) also explains that currently, leadership is the ability to “act with others to do things that could not be done by an individual alone”, hence “leadership is a form of empowerment not dominance or control” (

Ferguson 1984, p. 206). These views have been supported recently by

Kristinsson et al. (

2024, p. 239), who found that “ethical leaders prioritize the well-being of their team members and aim to protect, assist, develop, and empower them”, skills and traits possessed by women.

Blackmore (

2017) goes on to debunk another myth that women lack self-esteem and fear success. This is an issue of self-sabotage (

Vennes 2023), a theory put forward by

Horner (

1972) and

Condry and Dyer (

1976). These authors argue that women “fear” success because they lack self-esteem, are passive, and non-aggressive. Thus, the notion of leadership which is dominant in educational administrations, has been socially and historically constructed in a way that connects so-called “masculine” characteristics to leadership (

Blackmore 2017, p. 65). Women do not want to be seen as non ‘feminine’, thus, they are more anxious than males to take up leadership roles in case they fail, or because they fear that being a leader means they will, be alienated, become lonely, and be in conflict (

Carlson 1972) with their colleagues. In addition to self-sabotage (

Vennes 2023), women themselves sabotage other women (

Brock 2008).

As Blackmore explains, the trait approach embeds gender stereotypes. It ignores the learned behavior where boys are taught how to be rational, logical, and objective to suppress their feelings, and are encouraged to be dominant in social situations. Whereas girls learn to cultivate emotions at the expense of rationality, be passive, and embed dependence in their roles. One may argue these are the dominant theories of the 1980s and 1990s, yet these are the years that women who are now in a position to be able to apply for leadership roles in HTIs grew up in. Thus, these are the learned traits and stereotypes.

Therefore, from the above literature, another research question can be drawn. Do women in HTIs possess the leadership skills their male counterparts possess?

One author went as far as to argue that women tend to fear success (

Sassen 1980). Whilst Blackmore has put forward a number of reasons why women do not put up their hand to take leadership roles, other researchers have a different view.

Maranto and Griffin (

2011, p. 144) argue that women in academia ‘face a chilly climate’, where they are excluded from leadership, marginalized, face organizational and occupational segregation, and face structural constraints in developing personal networks because “homophily strongly influences network formation”. Academia, traditionally, has been a “highly dominated and gender-segregated” profession (

Maranto and Griffin 2011, p. 140), with women academics facing fewer opportunities “to develop homophiles ties within a department” (

Maranto and Griffin 2011, p. 144); and have less desirable network contacts than men due to stereotypes and attributions (

Ibarra and Smith-Lovin 1997). When there is a persistent perceived inequitable treatment, women will consider themselves excluded. However, the same will not be conceptualized, as such, by men where women are the majority in a department. It has been found (

Williams 1992;

Maranto and Griffin 2011) that in women dominating departments, men tokens do not experience exclusion, on the contrary, men are positively treated. The chilly climate can exist or be perceived to exist due to unconscious or implicit gender biases (

EIGE 2022, p. 29) where “men often benefit from positive bias, as they are presumed to have higher levels of competence and performance than their women colleagues”. The “chilly climate” in higher education breeds work–life conflict, career inflexibility, gender-blind and gender-biased research, inequality as well as unfairness (

EIGE 2022). Thus, the “chilly climate” will ultimately lead to an unhealthy working environment with increased stress, burnout (

Hyatt 2022), toxicity (

Frost 2002), gender-based violence, bullying, and harassment. Under such circumstances, staff become mentally disengage (

Hollis 2015) and students become negative in their studies and the success of the university as well as its future is undermined (

Gillespie et al. 2001).

For women academics to be in a position to express their wish to apply for leadership roles as deans or rectors they will need to have a full professorship which is more likely to happen once they reach the age group of at least 50. That means these women grew up in the years when such gender stereotypes existed. Thus, following the above assertion and the literature review, another research question remains to be investigated. What holds back, or what are the barriers women face from applying for leadership positions in HTIs?

Blackmore (

2017) utilizing the Foucauldian approach by reworking social theory from a critical perspective constructs a feminist critique of leadership in education arguing that the invisibility of women in leadership positions in education has “permeated the everyday commonsense notion of leadership”.

Fildes (

1983) raises the issue of language, where in some languages the word leader is in the masculine form then it is expected or there is a stereotype that males are leaders. In Cyprus, a male-dominated society, the term leader tends to be used concerning males.

Blackmore (

2017) also argues that the organization theory has made women “invisible” or “deficient” as leaders.

Blackmore (

2017) explains that women generally are excluded from leadership roles even though men and women are equal, women tend to have the authority over children, thus women have less time than their male counterparts to teach, research, and undertake administrative duties. She also explains that theories and values are androcentric, like the Marxist theory, which argues that once women enter the paid workforce, then there will be equality, a myopic approach.

Even though

Bryan et al. (

2021) are referring to sports organizations as extremely gendered they mirror many universities where women are pushed into the sideline and are not allowed to step up or voice their interests and wish to hold leadership roles. Thus, the authors in this pioneering research for Cyprus are explaining that in extremely gendered HTIs, women are held back from seeking leadership positions, perpetuating hegemonic masculinity.

Tyler et al. (

2019, p. 1319) have advocated that to tackle gender inequality one needs to “recognize the foundational nature of the male dominance and hegemonic masculinity” within an industry. This is what the current authors will initially endeavor to investigate. When students study in such ‘extremely gendered universities, they normalize the patriarchal notions and stereotypes that existed in the 1980s and 1990s, thus, future generations will resist change. Furthermore, HTIs which enjoy a “strong cultural legitimacy for masculine dominance” will face accusations of sexual harassment, bullying, gender inequality, gender pay gap reporting, and so on.

5. Results

The demographic profile of the respondents highlights a balanced and predominantly female sample (66.3%), with a broad age range (mean = 43.4, SD = 10.58) and a significant proportion in committed relationships (69.2%). This diversity is crucial for understanding the nuanced factors that may impact the pursuit of leadership roles in academia, particularly from a gender equality perspective. Also, demographic data indicate a well-rounded representation of academic staff (55.6%) and administrative staff (44.4%) with a notable majority from public institutions (61.4%). This diversity enriches the analysis, as it enables the exploration of how different institutional settings and professional roles might impact the pursuit of leadership roles, particularly concerning gender equity in academia. The combined data from public and private institutions, as well as academic and administrative staff, will provide a holistic view of the factors that influence career advancement and leadership opportunities in HTI. The data also set the stage for analyzing how personal and professional life intersects with career advancement in academic settings.

Research Question 1: Are HTIs considered extremely gendered environments?

We have found the first characteristic of the extremely gendered environment noted by

Sasson-Levy (

2011); there is an essentially hierarchical conception of gender where 47% of the respondents believe that the overall culture in their university is that those in higher positions make decisions based on their views and ignore the impact of their decisions on the rest of the university community (including staff and students). At the time of writing, in Cyprus, there is only one female rector in one private university and one female vice-rector in one of the public universities in Cyprus, i.e., for a total of 39 leadership positions (i.e., one rector and two vice-rectors in each of the 13 universities), only 5% are women, illustrating an under-representation of women in power and leadership and fulfilling the characteristic of being an extremely gendered environment, as advocated by

Burton (

2015) and

Sartore and Cunningham (

2007). This finding also reinforces the characteristic of hegemonic masculinity (

Anderson 2009). Furthermore, whilst 70% of respondents do not hold the belief that leadership is a men’s role, stereotypes like family obligations (83%), lack of time (66%), professional burnout (53%), and mansplaining (37%) have an impact on women seeking leadership roles, supporting the sexist stereotype characteristic of extremely gendered environments as advocated by

Aicher and Sagas (

2009). Thus, the picture that emerges is of a male-dominated environment in HTIs that perpetuates itself, providing support for

Bryan et al.’s (

2021) work on extremely gendered environments.

Around 38% of the respondents are not currently holding nor did they hold (36%) any leadership roles in the university (i.e., councils, senates, rectorates, deanships, or department heads); thus, the majority of the respondents did hold or are holding some form of leadership role. An interesting finding yielded by the analysis is that males and females are represented across various positions within the academic hierarchy. The data for current positions held by academic staff reveal several gendered patterns that highlight disparities in the representation of males and females across different roles. Specifically, males (17.6%) are significantly more represented than females (10.4%) in positions of university senate members, suggesting barriers for women in accessing high-influence governance positions. In the position of vice-rector, no female respondents currently hold the position of vice-rector, while 2.9% of male respondents do, reflecting a gender gap in senior executive roles. Concerning dean and department chair positions, more males are deans (5.9% vs. 3.5% females) and department chairs (17.6% vs. 9.6% females), indicating limited advancement for women to top leadership roles. For the program coordinator position, a significant gender gap exists, with nearly half of male respondents (48.5%) serving as program coordinators compared to 28.7% of females. Overall, men are more likely to hold senior leadership positions like rector, vice-rector, and dean, while women are somewhat more represented in roles like deputy dean or department vice-chair.

Concerning the questions about past positions held, responses revealed that a higher percentage of males (26.5%) than females (12.2%) previously served as university senate members, reinforcing the trend of male dominance in key governance roles. Regarding the positions of vice-rector and dean, only males reported having been vice-rectors (1.5%), and more males were deans (11.8% vs. 0.9% females), highlighting the historical underrepresentation of women in top academic leadership. Finally, past positions as program coordinators were also more common among males (45.6%) than females (33.0%), indicating consistent gender disparities in these roles over time. These findings, which are in agreement with other researchers (

Bryan et al. 2021;

Anderson 2009), suggest that men are more frequently in leadership roles with greater decision-making power both currently and historically, pointing to the systemic barriers affecting women’s career progression in leadership positions in HTIs. To promote gender equity, universities should consider targeted interventions, such as leadership development and equitable hiring and promoting practices, to support women’s advancement to senior leadership positions.

Furthermore, 39% of the female and 46% of the male respondents expressed interest in holding any leadership roles in their university. The majority of both genders in public HTIs (males 76% and females 64%) are interested in holding leadership positions. In contrast, only a minority (women 36% and males 24%) of both males and females in private HTIs are interested in holding leadership positions. Thus, in public HTIs, it is more likely that males would be interested in holding leadership positions, while the reverse was found in private HTIs.

If one is discussing a gendered environment, gender-based discrimination cannot be ignored. Gender-based discrimination was a notable concern for 28.7% of respondents, reporting personal experiences of such discrimination within their HTI. Additionally, 29.3% had heard of such experiences from others, although they had not experienced it themselves. In contrast, 26.9% of respondents had neither experienced nor heard about gender-based discrimination. Thus, some form of gender-based discrimination is expected to be found in extremely gendered academic environments.

Based on the above findings and the characteristics of extremely gendered environments (

Bryan et al. 2021), the authors have concluded that the findings relating to the first research question add credence to the assertion that HTIs are extremely gendered environments.

Research Question 2: Do women in HTI possess the leadership skills their male counterparts possess?

To explore whether women in HTI possess leadership skills comparable to their male counterparts, respondents were asked to identify key traits necessary for leadership in the academic community and then to indicate which traits they considered more prominent in men and women within their university.

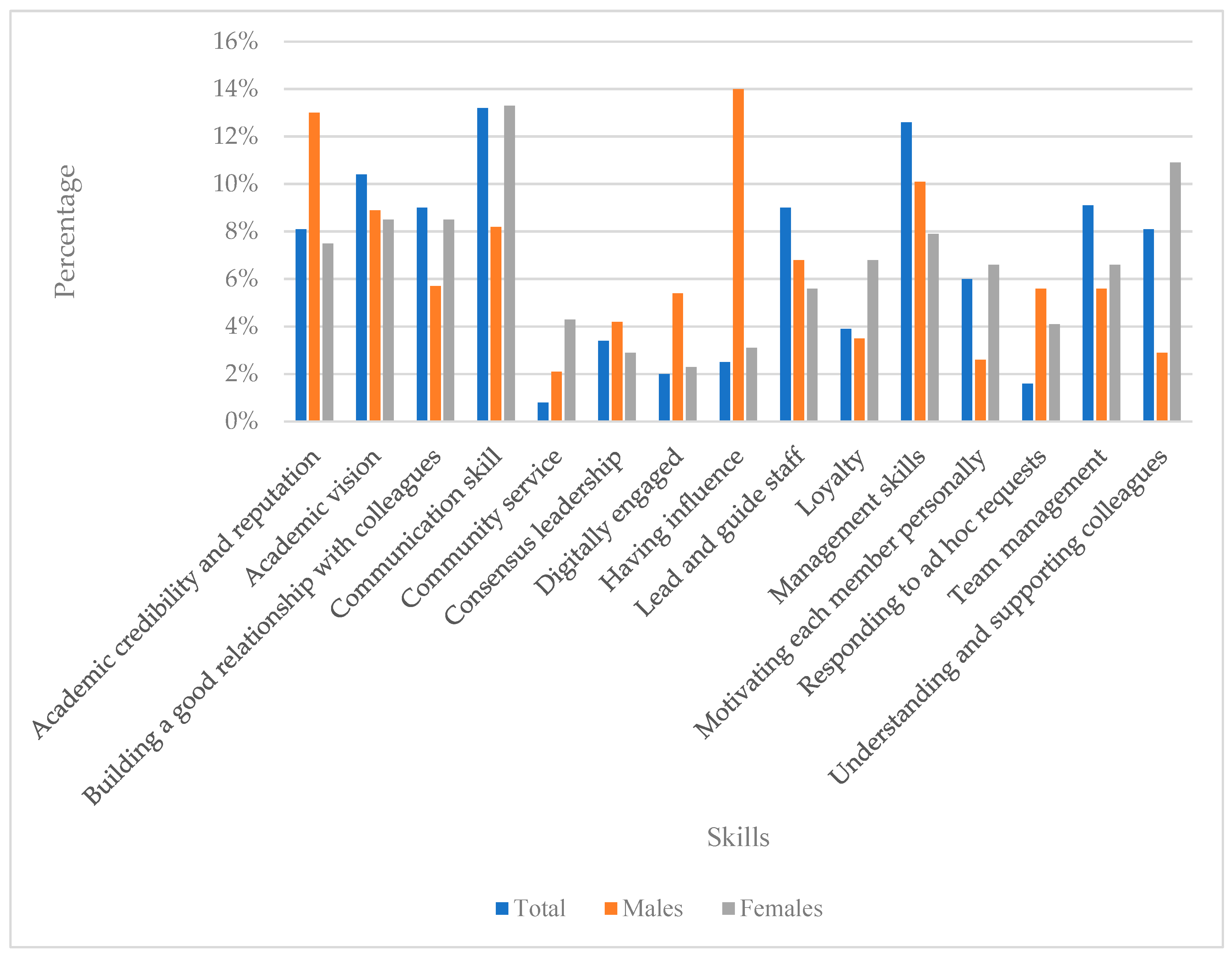

The respondents identified the following traits needed to be held by those in leadership roles in HTIs. The most frequently selected skills/traits included communication skills (13.2%), management skills (12.6%), academic vision (10.4%), team management skills (9.1%), and the ability to build good relationships with colleagues (9.0%). Academic credibility and reputation (8.2%) and understanding and supporting colleagues (8.2%) were also viewed as important.

Respondents identified the following skills/traits as being prominent in men from their HTIs: having influence (14.2%) and academic credibility and reputation (13.3%) were the most notable. Other skills/traits frequently associated with men included management skills (10.3%), academic vision (9%), and communication skills (8.3%).

Respondents identified the following skills/traits as being prominent in women in their higher institution: communication skills (13.5%), understanding and supporting colleagues (11.0%), and building good relationships with colleagues (8.6%). Academic vision (8.6%) and management skills (8.0%) were also considered prominent in women. The axis in

Figure 1 below represents the respondents’ selections.

In answering the research question above, with respect to whether women possess the leadership skills their male counterparts possess, it was found that different skills are upheld by the two genders. As indicated in the data and

Figure 1 (above), the six top skills (communication skills, management skills, academic vision, team management, building a good relationship with colleagues, understanding and supporting colleagues, and academic credibility and reputation) are expected to be held by those holding leadership positions in HTIs, and they are held equally by women and men. A greater proportion of males were found to hold management skills, academic vision, and academic credibility and reputation. In contrast, a greater proportion of women were found to possess traits such as communication skills, team management, and understanding and supporting colleagues.

The authors advocate that leadership in HTIs ought to be equally shared between the two genders to ensure that a broad range of skills is thus exhibited.

In comparing males and females that hold leadership roles in academic environments historically and currently, the following picture emerges. Most respondents (80%) believe that women and men are equally competent in leadership roles, even though males historically held such roles. It is also believed that women are currently assumed to be as good as men in such roles (67%) and both men and women are equally strong in networking (72%).

In responding to the research question above, we have found that women academics possess different leadership skills than their male counterparts. However, together, they hold the leadership skills expected of those holding such positions. The current authors advocate that leadership in academic institutions ought to be equally shared between the two genders to ensure that the requirement of a broad range of skills/traits is thus satisfied. Having an equal proportion of women and men in leadership positions will ensure that leadership skills and traits are covered, and that one gender does not overshadow the other.

Research question 3: What holds women back from applying for leadership roles in higher education?

The data reveal a complex web of factors that hold women back from applying for leadership positions in HTI. There are five such factors according to the respondents. Encouragement and support by the family are important for women to seek leadership roles in HTIs due to the excessive demands placed on the family, and individuals will need to maintain their academic status and research output as academics while holding such leadership positions. Most of the respondents (58%) reported feeling encouraged by their families to seek leadership roles. However, nearly 30% did not discuss leadership aspirations with their families, and 12% did not feel encouraged. A chi-square test of independence revealed a statistically significant association between gender and the responses to this question: χ2(2, N = 332) = 8.876, p = 0.012. Additionally, the contingency coefficient yielded a value of C = 0.161, p = 0.012, indicating a weak but significant association between gender and the response distribution across the categories of this question. The crosstabulation results indicate a variation in the distribution of responses between females and males. Specifically, we found that a higher percentage of females (63.8%) felt encouraged by their families to take leadership roles, compared to only 47.2% of males. A higher proportion of males (38.9%) than females (24.6%) did not discuss their intention to seek leadership positions with their families. This suggests that whilst women tend to discuss their intention to seek leadership positions in HTIs with their families and they do feel encouraged, they opt not to proceed. This may well be explained by the fact that the great majority of women (83.1%) felt that family obligations have an impact on them seeking leadership roles. On the other hand, only a small minority (17.8%) of males believe their family and obligations have an impact on them taking up leadership positions. This is underpinned by the male-dominating societal culture where family obligations are the primary responsibility of women.

Second, collegial support is an important factor in deciding to express an intention or interest in seeking leadership positions in HTIs. Unlike many other universities around the globe, in Cyprus, one needs to be elected to rectorate, council, senate, dean, vice dean, head/chair and deputy head/chair of department positions. Hence, an important determining factor is collegial support. It was found that the majority (68.8%) of those who expressed interest in leadership positions felt supported by both male and female colleagues. A chi-square test of independence was performed to examine the association between gender and respondents’ perceptions of collegial encouragement. The Pearson chi-square test indicated a significant association between gender and the perceptions of collegial encouragement: χ2(6, N = 332) = 14.873, p = 0.021. It is worth remarking that only 0.9% of women received collegial encouragement by men (compared to 2.8% of men receiving encouragement by men). Moreover, only 36.6% of women experienced backing from colleagues of both sexes, while 52.8% of men benefited from such dual-gender support. This suggests that the support network for women from both genders is often lacking, which can be a significant deterrent in seeking leadership roles. On the other hand, males are more likely to receive encouragement from both genders. Without strong collegial backing, women may feel isolated and less likely to pursue leadership opportunities. In investigating the drivers behind those findings, it was reported by some respondents (38%) that men in leadership roles build walls that are hard to overcome, and similarly, women sabotage women (39.8%).

Another factor influencing the decision to seek leadership roles is the sense of inclusiveness and the perception of fairness in decision-making. More than half of the respondents (53%) believe that those in leadership positions make decisions without considering the impact on the broader university community. This sense of exclusion from decision-making processes can contribute to feelings of disenfranchisement among women, leading them to believe that their input will be undervalued or ignored. This could deter them from seeking roles in which they fear they will not have a meaningful voice. The belief that leadership roles are accessible only to those with existing connections (52%) creates a challenge for women. This gatekeeping mentality reinforces an androgenic status quo that can be difficult for women to penetrate. Two-thirds of the respondents felt that decisions for leadership positions are attributable to factors other than merit, such as friendships, research collaborations, and men’s alliances, factors underpinning nepotism. Thus, when women believe that leadership roles are awarded based on factors, they have little control over, such as established friendships or “boys’ room alliances”, they may feel that their chances of being selected are slim, leading to self-exclusion from the application process. To overcome this barrier, and change the dominance of males, women need to be empowered and support each other rather than sabotaging one another.

The fourth factor is identity-based barriers which create concerns about biases related to the following: social status (31%), age (27%), political beliefs (27%), gender (23%), nationality (20%), sexual orientation (15%), and religious beliefs (11%). As illustrated with the above statistics, the majority of the respondents believe that leadership roles are accessible regardless of these factors; however, the sizeable minority who disagree reveals that biases and perceived discrimination create barriers. These perceptions can discourage women who identify with these marginalized groups from applying for leadership roles, as they may fear that their identity could negatively impact their chances of success. Thus, to redress these barriers, a motivator would be for the university to acknowledge the existence of marginalized groups and to take specific measures to address the imbalances that exist.

The fifth factor is gender-specific barriers: The widespread perception that women face more barriers than men in accessing leadership roles highlights the persistent gender inequality in HTIs. The overwhelming agreement that women face more barriers than men (67.7%) in accessing leadership roles underscores the prevalence of gender bias within HTIs. These barriers could include anything from lack of mentorship and gender stereotypes to the challenges of balancing work and family responsibilities. The perception of these barriers can be self-reinforcing, discouraging women from pursuing leadership roles because they believe the odds are stacked against them; thus, mentoring will enhance their skills. Given that women are tokens in leadership positions, this also means that there are limited role models, which create an additional challenge for women.

In responding to this question and utilizing the theories put forward by previously mentioned researchers, the authors have found that stereotypes, fear, and a chilly environment created barriers for women to express their interest in seeking leadership roles. For the third research question, a reliability analysis was conducted on eighteen questions related to the factors that impact women (eleven characteristics) and men (seven characteristics) in leadership roles to evaluate internal consistency. There are four characteristics not included for men; this was suggested by the external experts who reviewed the questionnaire at the pilot test because they do not apply to males. Both sets of items demonstrated good reliability, with Cronbach’s Alpha values of 0.84 for factors that impact women and 0.74 for factors that impact men. Then, two separate factor analyses were conducted on the items related to women and men. The factor analysis on the characteristics related to women extracted three components with eigenvalues greater than one, explaining a cumulative variance of 64.211%. The first component explained 39.761% of the variance. Varimax rotation resulted in a clearer separation of components. The first three questions loaded strongly on the first component (stereotype), the next three loaded strongly on a second component (fear), and the last five questions loaded on the third component (chilly climate). The factor analysis on the characteristics related to men extracted two components, explaining 59.917% of the variance. The first component explained 44.083% of the variance. After varimax rotation, the items generally loaded well on two components, with the first six items loading on the first component (stereotype and fear) and the last item showing strong loading on the second component (masculinity).

The factor analyses indicated distinct underlying factors within the items, with some items aligning more closely with certain components. This suggests that the items may be tapping into different dimensions of the constructs related to barriers and motivators for women in leadership roles in HTIs. These findings provide a robust basis for the further analysis and interpretation of data related to the third research question with respect to the factors influencing women’s participation in HTI leadership roles/positions.

As illustrated in

Table 1, it appears that women do not only need to overcome stereotypes that hold them back but also must overcome a number of factors that create fear for them, like a lack of belief in their own abilities, dissatisfaction because of a lack of professional credit, and toxic working environments. To a lesser extent, they also need to overcome chilly environments that exist due to the following beliefs: (a) that leadership is a man’s role, (b) that men who are already in leadership roles put up walls that are hard to overcome, (c) that women are ignored and marginalized, (d) that mansplaining occurs, and ( e) that women sabotage women.

In grouping the stereotypes and fears holding back men from leadership positions, it was found that family obligations, professional burnout, and lack of time are the main barriers. Unlike women, men have more self-confidence, do not need acknowledgment for their work, and do not fear toxicity. The fact that they believe that leadership is a man’s role reinforces the hegemonic masculinity theory in an extremely gendered HTI environment.

Addressing these challenges for women requires a multifaceted approach. This should include fostering a more inclusive and supportive culture, ensuring transparency and fairness in decision making, and actively encouraging and mentoring women (

Roth et al. 2024) to pursue leadership roles. Only by tackling these barriers head on can HTIs move toward true gender equality in leadership.

7. Discussion

Generally, leadership positions in HTIs tend to be held by men (

SHRM 2023). In this original contribution paper, the authors have supported

Bryan et al.’s (

2021) theory of extremely gendered environment in HTIs and the preservation of hegemonic masculinity (

Anderson 2009) with women being underrepresented in leadership positions. Another significant finding, which is in agreement with

Kirsch (

2018), is that women possess different leadership traits to their male colleagues; however, the current authors have found that both genders jointly hold the traits expected of those holding leadership positions in HTIs. Thus, leadership positions in HTIs should be shared by both genders and at least there should be an equal representation of both genders in the higher echelons of HTIs to ensure adequate representation of the skills required for such duties. Finally, the authors have found the barriers holding women back from seeking leadership roles are not only sexist stereotypes (

Aicher and Sagas 2009) but a combination of endogenic and exogenic fears (

Condry and Dyer 1976;

Sassen 1980), as well as the chilly climate created by their male counterparts (

Blackmore 2017) and sabotage by their female counterparts (

Brock 2008). However, a picture that emerged is that of nepotism, where those males in leadership choose to build walls to protect their position and not allow women to penetrate the higher echelons of HTIs.

Katuna (

2019) highlights that leaders “learn how to lead; they are not born knowing how to lead” (p. 63). As suggested by

Margolis and Romero (

1998), leadership is gained via socialization through education; peer groups (

McFarland and Thomas (

2006)) and mentoring (

Katuna (

2019)).

Roth et al. (

2024) also suggested mentoring and using role models as a plan to move the needle toward having more women in leadership positions in HTIs. However, to have role models and offer mentoring, one needs to have a pool of women and or men willing to devote time and energy towards mentoring. Academics work in a very competitive environment of publishing or perishing, thus devoting time and effort outside teaching, researching, and publishing is not their priority. As

Tsoukas’s (

2024) argued, being a leader is a sacrifice, not a privilege, sighting many leaders from Navalny to Martin Luther King. Are male leaders willing to sacrifice the time they have to research and publish for the benefit of their students and colleagues by devoting time to mentoring? Would women be as willing to do the same when they gain leadership positions in academia? Of course, HTIs can identify individuals who inspire with their behavior or individuals for whom women in HTIs have great admiration and create the pool of mentors. However, it is suggested that firstly HTIs ought to offer management training (

Astin and Astin 2000;

Morley 2013) to all staff approaching tenure to transform the academic leadership discipline (

Astin and Astin 2000) to one with an emphasis on human relations along with empowerment (

Kekale 2005). Secondly, once one makes it to a tenure position the HTIs ought to expect those individuals to devote part of their time to mentoring and guiding younger female academics and less time to publishing papers.

In agreement with some authors (

Gersick et al. 2000, p. 1027) “women and men live in different relational environments in academia” and as illustrated by EIGE, very little progress has been made in Cyprus to close the tenure gap between men and women (

Valian 1998, p. 234). Thus, the first policy implication put forward by the authors is to reconstruct female leadership by including women in the patriarchal discourse with the use of quotas. It is suggested that

Directive 2022/2381 (

European Parliament and Council 2022) should be extended to cover HTIs. The second suggestion made is that organizations (e.g., European Women Rectors Association (EWORA) and Athena Swan) empowering women to lead in academia ought to organize frequent workshops and conferences to raise awareness and build capacity on the issues of gender balance in leadership in academia, as well as to offer mentoring to senior academics wishing to take up leadership roles. Thirdly, mentoring at an individual level ought to be encouraged both at micro (institutional level) and macro levels (national or international levels), with women themselves seeking the opportunities to network with other women whether in their discipline or profession, to rise to the level they wish to reach. By ensuring a gender balance in leadership positions, there will be a maximization of leadership styles and traits, avoidance of rigid universalism, and a more equitable and ethical working environment.

Finally, having more women in leadership not only safeguards diversity but also navigates towards a more ethical environment, as women are considered by some authors (

Beu et al. 2003;

Dawson 1997;

Mason and Mudrack 1996;

Smith and Oakley 1997) to behave more ethically. This is in agreement with

Kennedy et al. (

2017) who hypothesized that women internalize morality into their identities more strongly than men, and

Kristinsson et al. (

2024), who found that the “female gender roles align closely with the ethical leadership role” (p. 240). Furthermore,

Maulidi et al. (

2023) have found that females are less likely to commit fraud, corruption or approve illegal or unethical behavior (

Torgler and Valev 2010), thus, the nepotism, toxicity, and other negative working environment conditions reported earlier by the authors will be addressed. It was not the authors’ intention to study the relationship of gender and ethics but merely to indicate that by navigating towards a gender-balanced leadership in HTIs, women who are considered to be more ethically oriented (

Mason and Mudrack 1996) than males ought to have the opportunity to lead if they so wish, thus encouraging their colleagues and students to follow their lead and behave in an ethical manner (

Brown and Treviño 2006;

De Roeck and Farooq 2018).