Ethical Leadership and Emotional Exhaustion: The Impact of Moral Intensity and Affective Commitment

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Ethical Leadership and Emotional Exhaustion

1.2. Mediating Role of Affective Commitment

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Ethical Aspects

2.3. Measures

2.4. Aggregation Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Reliability Analysis

3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.3. Convergent and Discriminant Validity

3.4. Validity Analysis

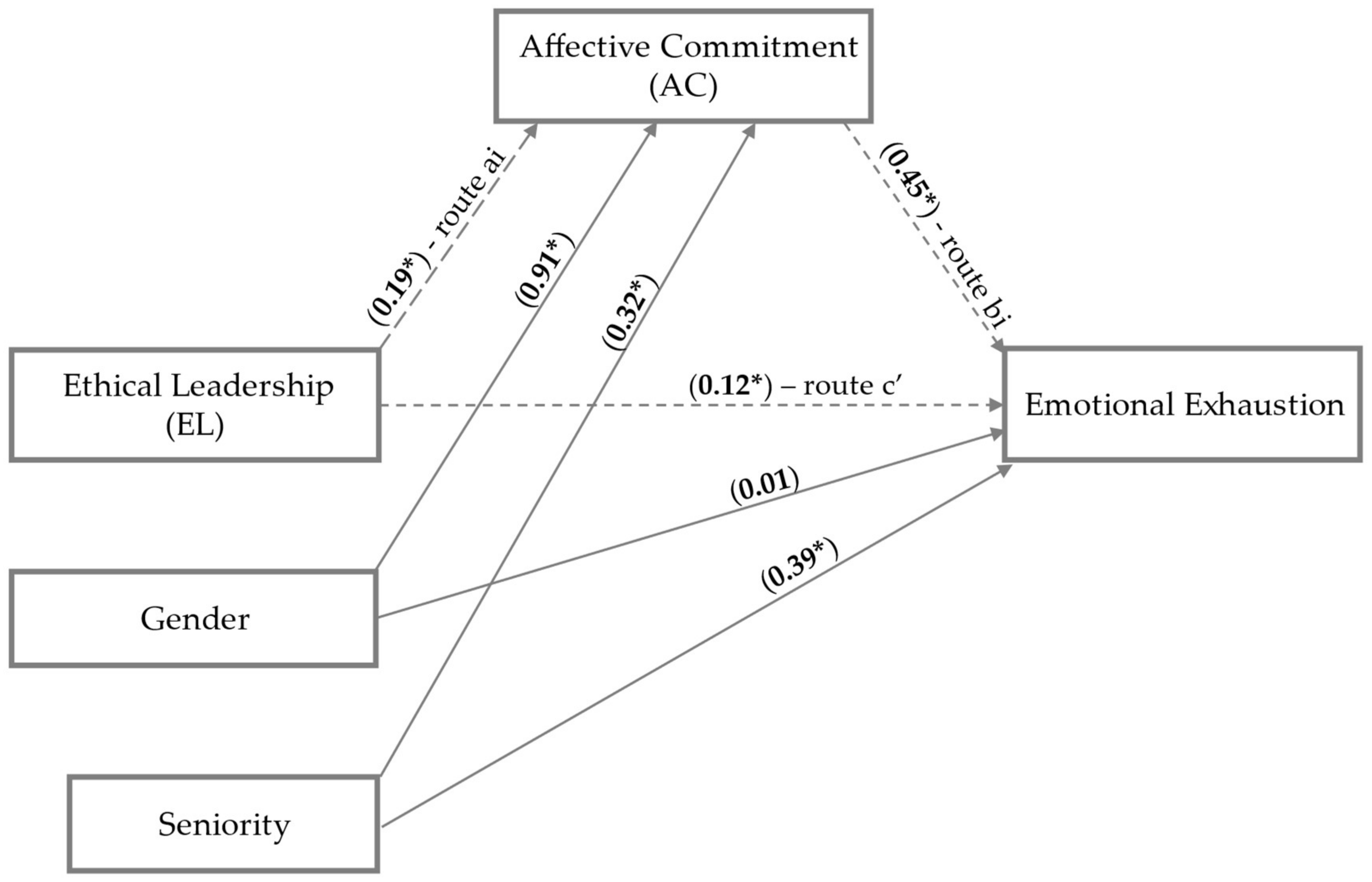

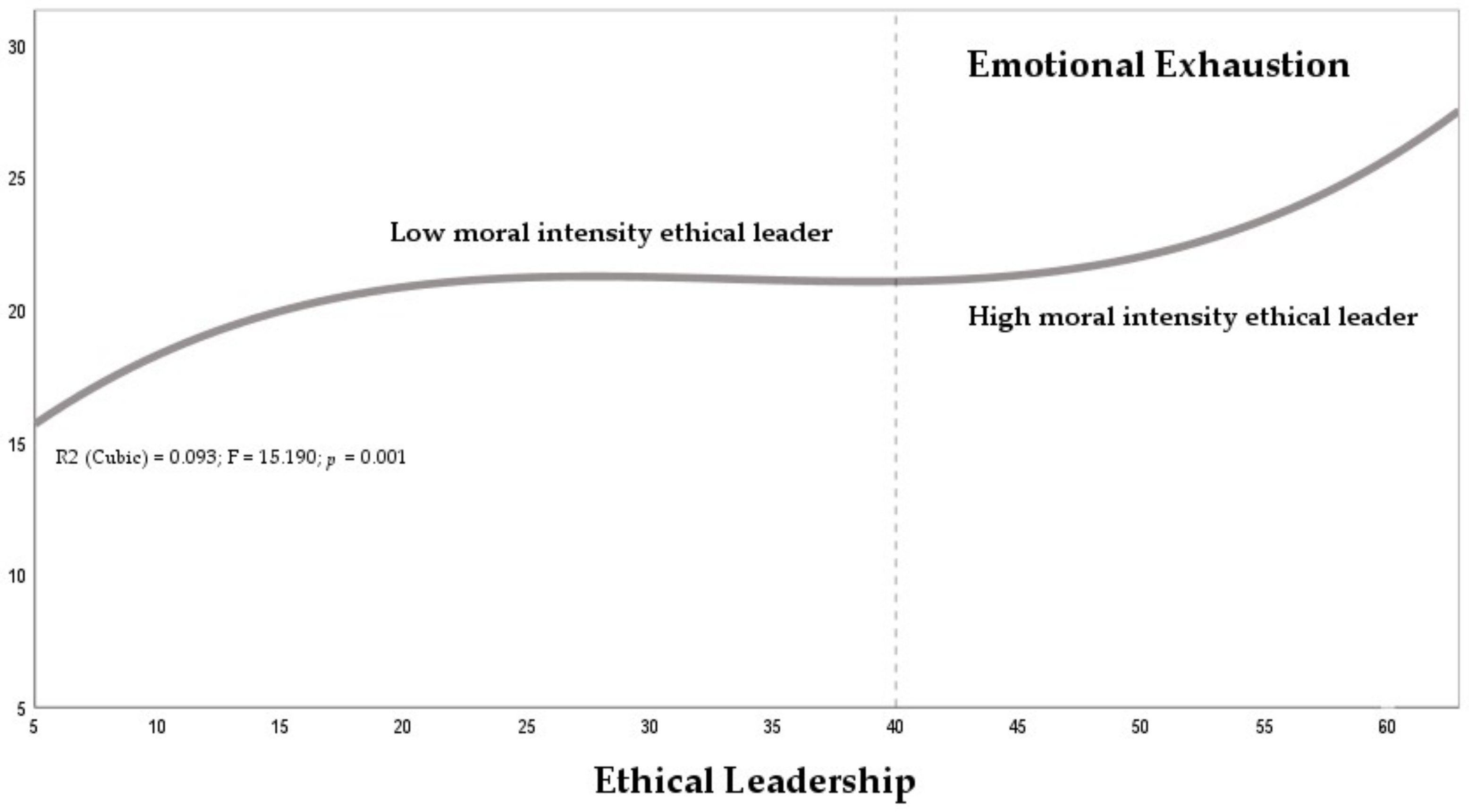

Hypothesis Testing

4. Discussion

Practical Implications and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aguinis, Herman, Jeffrey R. Edwards, and Kyle J. Bradley. 2017. Improving Our Understanding of Moderation and Mediation in Strategic Management Research. Organizational Research Methods 20: 665–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, Muhammad, Miao Qing, Jinsoo Hwang, and Hao Shi. 2019. Ethical Leadership, Affective Commitment, Work Engagement, and Creativity: Testing a Multiple Mediation Approach. Sustainability 11: 4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Albert. 1985. Model of Causality in Social Learning Theory. In Cognition and Psychotherapy. Boston: Springer, pp. 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonett, Douglas G., and Thomas A. Wright. 2015. Cronbach’s alpha reliability: Interval estimation, hypothesis testing, and sample size planning. Journal of Organizational Behavior 36: 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouraoui, Khadija, Sonia Bensemmane, Marc Ohana, and Marcello Russo. 2019. Corporate social responsibility and employees’ affective commitment. Management Decision 57: 152–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Michael E., and Linda K. Treviño. 2014. Do Role Models Matter? An Investigation of Role Modeling as an Antecedent of Perceived Ethical Leadership. Journal of Business Ethics 122: 587–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Michael E., Linda K. Treviño, and David A. Harrison. 2005. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 97: 117–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Shu-Cheng, and Shin-Guang Liang. 2013. When do subordinates’ emotion-regulation strategies matter? Abusive supervision, subordinates’ emotional exhaustion, and work withdrawal. The Leadership Quarterly 24: 125–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, Wynne W. 1998. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In Modern Methods for Business Research. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 295–358. [Google Scholar]

- Chughtai, Aamir, Marann Byrne, and Barbara Flood. 2015. Linking Ethical Leadership to Employee Well-Being: The Role of Trust in Supervisor. Journal of Business Ethics 128: 653–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Aaron, and Lilach Caspary. 2011. Individual Values, Organizational Commitment, and Participation in a Change: Israeli Teachers’ Approach to an Optional Educational Reform. Journal of Business and Psychology 26: 385–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, Russell, and Marie S. Mitchell. 2005. Social Exchange Theory: An Interdisciplinary Review. Journal of Management 31: 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Peng, Yanhui Mao, Yufan Shen, and Jianhong Ma. 2021. Moral Identity and Subjective Well-Being: The Mediating Role of Identity Commitment Quality. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 9795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cullinan, Charles, Dennis Bline, Robert Farrar, and Dana Lowe. 2008. Organization-Harm vs. Organization-Gain Ethical Issues: An Exploratory Examination of the Effects of Organizational Commitment. Journal of Business Ethics 80: 225–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hoogh, Annebel H. B., and Deanne N. Den Hartog. 2008. Ethical and despotic leadership, relationships with leader’s social responsibility, top management team effectiveness and subordinates’ optimism: A multi-method study. The Leadership Quarterly 19: 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekberg, Katie, Stuart Ekberg, Lara Weinglass, and Susan Danby. 2021. Pandemic morality-in-action: Accounting for social action during the COVID-19 pandemic. Discourse & Society 32: 666–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Jie, Yucheng Zhang, Xinmei Liu, Long Zhang, and Xiao Han. 2018. Just the Right Amount of Ethics Inspires Creativity: A Cross-Level Investigation of Ethical Leadership, Intrinsic Motivation, and Employee Creativity. Journal of Business Ethics 153: 645–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flatau-Harrison, Huw, Mark A. Griffin, and Marylène Gagné. 2021. Should We Agree to Disagree? The Multilevel Moderated Relationship Between Safety Climate Strength And Individual Safety Motivation. Journal of Business and Psychology 36: 679–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, Claes, and David F. Larcker. 1981. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research 18: 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Jingtao, Yijing Long, Qi He, and Yazhen Liu. 2020. Can ethical leadership improve employees’ well-being at work? Another side of ethical leadership based on organizational citizenship anxiety. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumis, Renata Rego Lins, Gustavo Adolpho Junqueira Amarante, Andréia de Fátima Nascimento, and José Mauro Vieira Junior. 2017. Moral distress and its contribution to the development of burnout syndrome among critical care providers. Annals of Intensive Care 7: 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, Marylène, and Edward L. Deci. 2005. Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior 26: 331–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, Tomás Félix, and Manuel Guillén. 2008. Organizational Commitment: A Proposal for a Wider Ethical Conceptualization of ‘Normative Commitment’. Journal of Business Ethics 78: 401–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guohao, Li, Sabeeh Pervaiz, and He Qi. 2021. Workplace Friendship is a Blessing in the Exploration of Supervisor Behavioral Integrity, Affective Commitment, and Employee Proactive Behavior—An Empirical Research from Service Industries of Pakistan. Psychology Research and Behavior Management 14: 1447–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, Joseph F., William C. Black, Barry J. Babin, Rolph E. Anderson, and Ronald L. Tatham. 2006. Multivariate Data Analysis. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Prentice Hall, vol. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2018. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs 85: 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, Stevan E., Jonathon R.B. Halbesleben, Jean-Pierre Neveu, and Mina Westman. 2018. Conservation of Resources in the Organizational Context: The Reality of Resources and Their Consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 5: 103–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoch, Julie E., and Steve W. J. Kozlowski. 2014. Leading virtual teams: Hierarchical leadership, structural supports, and shared team leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology 99: 390–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanzeb, Sadia, and Tasneem Fatima. 2018. How Workplace Ostracism Influences Interpersonal Deviance: The Mediating Role of Defensive Silence and Emotional Exhaustion. Journal of Business and Psychology 33: 779–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Lixin, and Matthew J. Johnson. 2018. Meaningful Work and Affective Commitment: A Moderated Mediation Model of Positive Work Reflection and Work Centrality. Journal of Business and Psychology 33: 545–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junça Silva, Ana, Alexandra Almeida, and Carla Rebelo. 2024. The effect of telework on emotional exhaustion and task performance via work overload: The moderating role of self-leadership. International Journal of Manpower 45: 398–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieserling, André. 2019. Blau 1964: Exchange and Power in Social Life. In Schlüsselwerke der Netzwerkforschung. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, pp. 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Hyewon, and Joo-Eon Jeon. 2018. Daily Emotional Labor, Negative Affect State, and Emotional Exhaustion: Cross-Level Moderators of Affective Commitment. Sustainability 10: 1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapalme, Matthew L., Felipe Rojas-Quiroga, Julio A. Pertuzé, Pilar Espinoza, Carolina Rojas-Córdova, and Juan Felipe Ananias. 2023. Emotion Regulation Can Build Resources: How Amplifying Positive Emotions Is Beneficial for Employees and Organizations. Journal of Business and Psychology 38: 539–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Chih-Jen, and Stanley Y. B. Huang. 2019. Double-edged effects of ethical leadership in the development of Greater China salespeople’s emotional exhaustion and long-term customer relationships. Chinese Management Studies 14: 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Hyewon, Saemi An, Ga Young Lim, and Young Woo Sohn. 2021. Ethical Leadership and Followers’ Emotional Exhaustion: Exploring the Roles of Three Types of Emotional Labor toward Leaders in South Korea. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 10862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Jin, Christina J. Resick, Joseph A. Allen, Andrea L. Davis, and Jennifer A. Taylor. 2024. Interplay between Safety Climate and Emotional Exhaustion: Effects on First Responders’ Safety Behavior and Wellbeing Over Time. Journal of Business and Psychology 39: 209–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemoine, G. James, Chad A. Hartnell, and Hannes Leroy. 2019. Taking Stock of Moral Approaches to Leadership: An Integrative Review of Ethical, Authentic, and Servant Leadership. Academy of Management Annals 13: 148–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Jian-Bin, Eva Yi Hung Lau, and Derwin King Chung Chan. 2023. Moral obligation to follow anti-COVID-19 measures strengthens the mental health cost of pandemic burnout. Journal of Affective Disorders 328: 341–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Weiwei, Zhiqing E. Zhou, and Xin-Xuan Che. 2019. Effect of Workplace Incivility on OCB Through Burnout: The Moderating Role of Affective Commitment. Journal of Business and Psychology 34: 657–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loi, Raymond, Long W. Lam, Hang Yue Ngo, and Sok-ian Cheong. 2015. Exchange mechanisms between ethical leadership and affective commitment. Journal of Managerial Psychology 30: 645–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukacik, Eden-Raye, and Joshua S. Bourdage. 2019. Exploring the Influence of Abusive and Ethical Leadership on Supervisor and Coworker-Targeted Impression Management. Journal of Business and Psychology 34: 771–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matherne, Curtis F., J. Kirk Ring, and Steven Farmer. 2018. Organizational Moral Identity Centrality: Relationships with Citizenship Behaviors and Unethical Prosocial Behaviors. Journal of Business and Psychology 33: 711–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, Lucy M., and Diane R. Edmondson. 2020. Overcoming emotional exhaustion in a sales setting. Journal of Global Scholars of Marketing Science 30: 229–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, John P., Natalie J. Allen, and Catherine A. Smith. 1993. Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. Journal of Applied Psychology 78: 538–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Qing, Alexander Newman, Jia Yu, and Lin Xu. 2013. The Relationship Between Ethical Leadership and Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior: Linear or Curvilinear Effects? Journal of Business Ethics 116: 641–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Shenjiang, Chu-Ding Ling, and Xiao-Yun Xie. 2019. The Curvilinear Relationship Between Ethical Leadership and Team Creativity: The Moderating Role of Team Faultlines. Journal of Business Ethics 154: 229–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morata-Ramirez, Mª Ángeles, Francisco Holgado Tello, María Isabel Barbero-García, and Gonzalo Mendez. 2015. Análisis factorial confirmatorio. Recomendaciones sobre mínimos cuadrados no ponderados en función del error Tipo I de Ji-Cuadrado y RMSEA. Acción Psicológica 12: 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negiş Işik, Ayşe. 2020. Ethical leadership and school effectiveness: The mediating roles of affective commitment and job satisfaction. International Journal of Educational Leadership and Management 8: 60–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okpozo, Afokoghene Z., Tao Gong, Michelle Campbell Ennis, and Babafemi Adenuga. 2017. Investigating the impact of ethical leadership on aspects of burnout. Leadership & Organization Development Journal 38: 1128–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Jong Gyu, Weichun Zhu, Bora Kwon, and Hojin Bang. 2023. Ethical leadership and follower unethical pro-organizational behavior: Examining the dual influence mechanisms of affective and continuance commitments. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 34: 4313–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Páez, Iliana, and Elvira Salgado. 2016. When deeds speak, words are nothing: A study of ethical leadership in Colombia. Business Ethics: A European Review 25: 538–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prem, Roman, Bettina Kubicek, Stefan Diestel, and Christian Korunka. 2016. Regulatory job stressors and their within-person relationships with ego depletion: The roles of state anxiety, self-control effort, and job autonomy. Journal of Vocational Behavior 92: 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Flores, Fabio Anselmo. 2019. Fundamentos Epistémicos de la Investigación Cualitativa y Cuantitativa: Consensos y Disensos. Revista Digital de Investigación en Docencia Universitaria 13: 101–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, Carlos. 2023a. Curvilinear relationship between ethical leadership and creativity within the Colombian electricity sector. The mediating role of work autonomy, affective commitment, and intrinsic motivation. Revista iberoamericana de estudios de desarrollo = Iberoamerican Journal of Development Studies 12: 74–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, Carlos. 2023b. Teleworking and emotional exhaustion in the Colombian electricity sector: The mediating role of affective commitment and the moderating role of creativity. Intangible Capital 19: 207–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, Carlos. 2023c. Selfish Ethical Climate and Teleworking in the Colombian Electricity Sector. The Moderating Role of Ethical Leadership. Acta Colombiana de Psicología 26: 169–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, Carlos. 2023d. Ethical leadership and benevolent climate. The mediating effect of creative self-efficacy and the moderator of continuance commitment. Revista Galega de Economía 32: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, Carlos. 2023e. Ethical Leadership and Organizational Commitment. The Unexpected Role of Intrinsic Motivation. Revista Universidad y Empresa 25: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, Carlos, and Nury Milena Muriel-Morales. 2023. Liderazgo ético, motivación intrínseca y comportamiento creativo en el sector eléctrico colombiano. Revista Venezolana de Gerencia: RVG 28: 1648–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, Carlos, Elisenda Tarrats-Pons, and José Antonio Corral-Marfil. 2023. Effects of Intensity of Teleworking and Creative Demands on the Cynicism Dimension of Job Burnout. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, Carlos, José Antonio Corral-Marfil, and Elisenda Tarrats-Pons. 2024. Relationship between Personal Ethics and Burnout: The Unexpected Influence of Affective Commitment. Administrative Sciences 14: 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, Wilmar B., Michael Leiter, Cristina Maslach, and Susan E. Jackson. 1996. Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey. In The Maslach Burnout Inventory: Test Manual. Edited by C. Maslach, S.E. Jackson and M.P. Leiter. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Maie, Marlies Schümann, and Sylvie Vincent-Höper. 2021. A conservation of resources view of the relationship between transformational leadership and emotional exhaustion: The role of extra effort and psychological detachment. Work & Stress 35: 241–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stouten, Jeroen, Marius van Dijke, David M. Mayer, David De Cremer, and Martin C. Euwema. 2013. Can a leader be seen as too ethical? The curvilinear effects of ethical leadership. The Leadership Quarterly 24: 680–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Guiyao, Ho Kwong Kwan, Deyuan Zhang, and Zhou Zhu. 2016. Work–Family Effects of Servant Leadership: The Roles of Emotional Exhaustion and Personal Learning. Journal of Business Ethics 137: 285–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, Cristina, Guillermo A. Cañadas, Raimunda Aguayo, Rafael Fernández, and Emilia I. de la Fuente. 2014. Which occupational risk factors are associated with burnout in nursing? A meta-analytic study. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology 14: 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washburn, Nicholas. S., Kelly L. Simonton, Kevin Andrew R. Richards, and Ye Hoon Lee. 2022. Examining Role Stress, Emotional Intelligence, Emotional Exhaustion, and Affective Commitment Among Secondary Physical Educators. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 41: 669–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojdylo, Kamila, Nicola Baumann, and Julius Kuhl. 2017. The Firepower of Work Craving: When Self-Control Is Burning under the Rubble of Self-Regulation. PLoS ONE 12: e0169729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Conna. 2014. Does Ethical Leadership Lead to Happy Workers? A Study on the Impact of Ethical Leadership, Subjective Well-Being, and Life Happiness in the Chinese Culture. Journal of Business Ethics 123: 513–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurtkoru, E. Serra, and Nabiallah Ebrahimi. 2017. The relationship between affective commitment and unethical pro-organizational behavior: The role of moral disengagement. Research Journal of Business and Management 4: 287–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Hongdan, and Jiarui Jiang. 2022. Role stress, emotional exhaustion, and knowledge hiding: The joint moderating effects of network centrality and structural holes. Current Psychology 41: 8829–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Dianhan, L. Alan Witt, Eleanor Waite, Emily M. David, Marinus van Driel, Daniel P. McDonald, Kori R. Callison, and Loring J. Crepeau. 2015. Effects of ethical leadership on emotional exhaustion in high moral intensity situations. The Leadership Quarterly 26: 732–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Hao, and Jingyi Chen. 2021. How Does Psychological Empowerment Prevent Emotional Exhaustion? Psychological Safety and Organizational Embeddedness as Mediators. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Hao, Song Liu, Yuling He, and Xiaoye Qian. 2022. Linking ethical leadership to employees’ emotional exhaustion: A chain mediation model. Leadership & Organization Development Journal 43: 734–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Hao, Xinyi Sheng, Yulin He, and Xiaoye Qian. 2020. Ethical Leadership as the Reliever of Frontline Service Employees’ Emotional Exhaustion: A Moderated Mediation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Weichun, Linda K. Treviño, and Xiaoming Zheng. 2016. Ethical leaders and their followers: The transmission of moral identity and moral attentiveness. Business Ethics Quarterly 26: 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | N | M | SD | G | A | EL | AC | EE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (G) | 1 | 0.39 | 0.49 | |||||

| Seniority (A) | 1 | 3.58 | 1.84 | 0.037 | ||||

| Ethical Leadership (EL) | 10 | 51.60 | 8.22 | −0.049 | −0.165 * | 0.830 | ||

| Affective Commitment (AC) | 6 | 29.81 | 3.82 | 0.082 | 0.073 | 0.291 * | 0.830 | |

| Emotional Exhaustion (EE) | 5 | 23.11 | 5.55 | 0.028 | 0.129 * | 0.372 * | 0.445 * | 0.810 |

| Goodness of Fit Measure | Acceptable Fit Levels | Results |

|---|---|---|

| CMIN (χ2) | χ2 (small) | 465.12 |

| χ2gl | <3 | 2.80 |

| RMSEA | <0.06 | 0.046 |

| SRMSR | <0.08 | 0.062 |

| GFI | >0.90 | 0.926 |

| IFI | >0.90 | 0.922 |

| CFI | >0.90 | 0.914 |

| NFI | >0.90 | 0.921 |

| ALPHA 1 | CR 2 | CFC 3 | AVE 4 | VD 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EL | 0.92 | >1.96 | 0.850 | 0.690 | 0.830 |

| AC | 0.86 | >1.96 | 0.830 | 0.690 | 0.830 |

| EE | 0.90 | >1.96 | 0.860 | 0.650 | 0.810 |

| Effect | Route | β | p | t | ES | LLCI | ULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (EL 1–AC 2): R = 0.331; R2 = 0.110; SE = 20.76; F = 18.200; p = 0.001 | ||||||||

| EL–AC | ai | 0.185 | 0.001 | 6.960 | 0.027 | 0.133 | 0.238 | |

| Gender–AC | - | 0.914 | 0.035 | 2.117 | 0.442 | 0.067 | 1.806 | |

| Seniority–AC | - | 0.325 | 0.006 | 2.743 | 0.119 | 0.093 | 0.560 | |

| Model 2 (EL–EE 3; AC–EE): R = 0.482; R2 = 0.232; SE = 23.91; F = 33.471; p = 0.001 | ||||||||

| AC–EE | bi | 0.453 | 0.001 | 8.687 | 0.051 | 0.343 | 0.543 | |

| EL–EE (Direct) | c’ | 0.116 | 0.001 | 3.860 | 0.030 | 0.057 | 0.175 | |

| EL–EE (Total) | c | 0.198 | 0.001 | 6.420 | 0.031 | 0.036 | 0.293 | |

| Gender–EE | - | 0.014 | 0.968 | 0.040 | 0.477 | −0.918 | 0.956 | |

| Seniority–EE | - | 0.394 | 0.002 | 3.059 | 0.129 | 0.141 | 0.647 | |

| Indirect Mediation Effect: β = 0.082, SE = 0.018, 95% CI [0.050, 0.121] | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santiago-Torner, C.; González-Carrasco, M.; Miranda Ayala, R.A. Ethical Leadership and Emotional Exhaustion: The Impact of Moral Intensity and Affective Commitment. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 233. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14090233

Santiago-Torner C, González-Carrasco M, Miranda Ayala RA. Ethical Leadership and Emotional Exhaustion: The Impact of Moral Intensity and Affective Commitment. Administrative Sciences. 2024; 14(9):233. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14090233

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantiago-Torner, Carlos, Mònica González-Carrasco, and Rafael Alberto Miranda Ayala. 2024. "Ethical Leadership and Emotional Exhaustion: The Impact of Moral Intensity and Affective Commitment" Administrative Sciences 14, no. 9: 233. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14090233

APA StyleSantiago-Torner, C., González-Carrasco, M., & Miranda Ayala, R. A. (2024). Ethical Leadership and Emotional Exhaustion: The Impact of Moral Intensity and Affective Commitment. Administrative Sciences, 14(9), 233. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14090233