Abstract

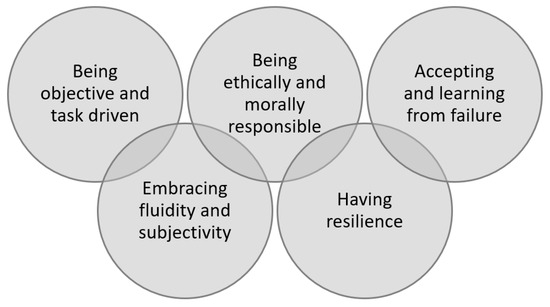

This research investigates how university students define and perceive success, an area that is increasingly important to ensuring that a university’s brand remains aligned to the expectations of future students. Over the next decade, university students will comprise members of Generation Z (Gen Z), and by recognizing this group of students’ preferences and aspirations, universities can tailor their branding, educational portfolio, and overall campus experiences to ensure that together they resonate and satisfy evolving needs and demands. Using data based on a sample of Gen Z undergraduate students undertaking their degrees at three case study UK post-1992 universities, this research adopted an exploratory, interpretivist methodology. Data collected from semi-structured interviews were analyzed using recursive abstraction to identify underlying patterns and trends within the data. The research identified five key themes that Gen Z are using to define success, and these are the following: (1) being objective and task-driven; (2) embracing fluidity and subjectivity; (3) being ethically and morally responsible; (4) having resilience; and (5) accepting and learning from failure. Recommendations were made for actions that universities should start to take to enable them to work toward achieving this.

1. Introduction

In today’s dynamic and metric-driven higher education landscape (Polkinghorne et al. 2017), in which universities are increasingly accountable for student outcomes and satisfaction, aligning institutional goals with student perceptions of success is crucial for fostering a supportive and enriching learning environment. Accordingly, understanding how success is perceived by the generation of potential new university students, known as Generation Z (Gen Z) (Dolot 2018), is crucial if universities are going to effectively project an aligned brand and meet the evolving needs and expectations of this key demographic (O’Sullivan et al. 2024).

Gen Z represents a departure from previous generations. Born between 1995 and 2012 (Singh 2014), Gen Z now represents approximately 70% of the United Kingdom (UK) undergraduate student body according to the Higher Education Statistics Agency (2024), and they think differently because they were immersed in digital technology while their brains were still developing (Seemiller and Grace 2018). Typical characteristics of this include shorter attention spans and the need to be continuously engaged. Research indicates that this Gen Z cohort of students responds to learning in new ways, and we therefore need to find different approaches to enable them to excel (Phillips and Trainor 2014).

Globalization and technological advancements are currently reshaping traditional mindsets and hierarchies across higher education (Woodard et al. 2011). Globalization is opening up higher education to increased competition from institutions from around the world (Lee and Stensaker 2021). For example, universities in the UK now must compete not just nationally, but also internationally for students, staff, research funding, and even reputation (Hall et al. 2018). As a result, the student body in the UK is now much more diverse, but this in turn means that students come from a wider range of countries and cultural backgrounds and so their expectations are more varied (Mercer-Mapstone and Bovill 2020). This diversity may be represented in many ways including through gender, ethnicity and/or socioeconomic backgrounds. These students may also be the first from their family (excluding siblings) who have received a university education (Coombs 2021, p. 9).

In terms of technological integration, advancements in technology have transformed teaching and learning in higher education (Criollo-C et al. 2021). Online learning platforms, digital resources, and multimedia tools have become integral parts of many courses, offering increased levels of both flexibility and accessibility to students (Marks and Thomas 2022). Research collaboration has also benefited from these technological developments as digital communication tools and shared databases are enabling researchers to work together irrespective of their geographical location (Hall et al. 2018; Haley et al. 2022).

However beneficial these changes may be, these evolutions also bring the risk of widening socioeconomic gaps as not all students have equal access to digital resources or opportunities, leading to disparities in educational outcomes for some (Selwyn 2010). As a result, this necessitates that universities, and other higher education providers, seek to foster higher levels of inclusivity and diversity to minimize the opportunities for potential disparities. Therefore, appealing to Gen Z requires universities to adapt to their new expectations and preferences, while staying true to their own core mission of providing a quality education combined with a series of life-enriching experiences.

By understanding and addressing the unique challenges of appealing to Gen Z, universities may be better positioned to attract, engage, and retain this crucial student demographic (Chapleo and O’Sullivan 2017; Chen 2022; Naheen and Elsharnouby 2024). Unpacking and understanding what Gen Z considers success to look like is therefore pivotal for several reasons, including the development of a stronger sense of identity and belonging, which will generate improved levels of both student satisfaction and retention.

Furthermore, by gaining insight into students’ definitions of success, universities may be more able to tailor their programs, services, and resources to meet the diverse needs and aspirations of their student body (Xiao et al. 2023; Khan and Hemsley-Brown 2021). This proactive approach may not only enhance student engagement and retention but may also contribute to overall institutional effectiveness and reputation (Lee et al. 2019; Kethüda 2023). Moreover, by incorporating student perspectives into their strategic planning and decision-making processes, universities may be able to foster a deeper culture of empowerment and continuous improvement. Universities that demonstrate an understanding of Gen Z’s concept of success will be able to enhance their brand image and so appeal to this key demographic by showcasing how their institution can specifically help this group of students to achieve their full potential (Gardiana et al. 2023; Schlesinger et al. 2023; Song et al. 2023).

Ultimately, by understanding what success means to their students, universities may be better able to fulfill their mission of nurturing future leaders, scholars, and global citizens. In essence, by understanding what Gen Z considers the concept of success to look like, higher education providers will be able to better serve their students, enhance their brand, and prepare their graduates for employment in a rapidly changing world.

2. Conceptualizing Success

Success is a subjective concept which holds a multitude of definitions depending upon the perspective of the individual (Weatherton and Schussler 2021). Its etymological origins trace back to Latin and it is derived from “successus”, which signifies an advance or happy outcome, stemming from ”succedere”, meaning to come after. In more recent times, “success” has since been associated with the accomplishment of desired ends and/or a favorable result.

In its literal term, success can denote “the accomplishment of an aim or a purpose” (Waite 2012) or “achieving the results wanted or hoped for” (McIntosh 2011). These definitions highlight the attainment of a positive outcome. However, in reality, the interpretation of success is multifaceted and varies significantly across people, cultures, and scenarios (Kuh et al. 2006).

Generally understood as the realization of goals or activities aimed at fulfillment, success is a dynamic construct (Baczko-Dombi and Wysmułek 2015). It involves setting and achieving positive goals. Success is therefore akin to a journey, not a destination, and is characterized by a continual re-adjustment, re-assessment, and re-measurement as goals may evolve over time, with newer aspirations replacing original ambitions (Müller and Turner 2010).

The perception of success is often influenced by individual experiences, the environment, and social constructs. Exploring and unpacking the factors that shape success offers valuable insights into society (Baczko-Dombi and Wysmułek 2015). Overall, success is an evolving concept, reflecting the dynamic nature of human endeavors and aspirations.

Empirical research has delved into the fundamental factors influencing success and has highlighted elements such as hard work, quality education, and networking (Baczko-Dombi and Wysmułek 2015). Additionally, motivation is a crucial determinant of success (Goleman 1996). According to Korda (1977), a genuine desire to succeed is essential, necessitating the cultivation of a true passion for achievement. Korda’s research further enforces the significance of desire, resilience, determination, and opportune timing as prevalent drivers of success.

Success holds different meanings for different people. To some, it represents a highly coveted achievement, while for others, it embodies the feelings of happiness and satisfaction (Uusiautti 2013). Mainstream culture often shapes perceptions of success, with attributes such as power, wealth, and status being commonly associated with it (Gaubert and Louvet 2021). However, for many, true success lies in making a positive impact on the lives of others. Alternatively, some may find fulfillment in a life devoted to serving a higher purpose, such as devotion to their religion (Chua and Rubenfeld 2014). Regardless of the specific interpretation, Korda asserts that setting realistic goals and achieving them is fundamental to success (Korda 1977).

Gladwell (2008) asserts success is not exclusively due to individual merit, but often a product of the world in which people grew up. This suggests that opportunity plays a critical role in our expectations of success. Furthermore, Gladwell (2008) suggests success can arise from the steady accumulation of advantages: for example, when and where you were born, your parents’ careers, and the circumstances of your upbringing. Sociologist Robert Merton (1968) famously called this phenomenon the “Matthew Effect”, after the New Testament bible verse in the Gospel of Matthew. This verse suggests that those who are already successful are more likely to be given opportunities that lead to further success (Gladwell 2008). The “Matthew Effect” is an accumulated advantage in which “the rich get richer, and the poor get poorer” (Gladwell 2008, p. 30). Gladwell (2008, p. 67) also suggests that luck and success are correlated. “Success is not exceptional or mysterious. It is grounded in a web of advantages and inheritances, some deserved, some not, some earned, some just plain lucky”. Korda (1977) reinforces this for the American success story, saying that luck has always played a significant role.

Morality in the pursuit of success is also a recurring theme in the literature. The literature suggests that our attitudes relating to how successful a person is are established early on, and that measurement of how successful a person is can be influenced enormously by their behavior. Furthermore, a focus on ethical decision-making on the journey to success is considered to be important in some instances. Characteristics and traits such as self-awareness (Goleman 1996), self-presentation (Goleman 2007), and authenticity (Albreght 2006) have been recognized as impacting on the success experienced in our lives. Furthermore, Race (2019, p. 213) states that “confidence is perhaps the single most important pre-determinant of success”, i.e., the belief in our own ability to achieve is considered a key factor in enabling us to be successful.

For the most part, scholars represent a collective view that success is a positive achievement that offers great reward. While success cannot insulate us from emotional and physical danger, it is widely agreed upon that success is far more comfortable than failure (Uusiautti 2013). However, there is also a body of evidence that views success as being problematic and that believes once the initial thrill wears off, it can cause stress and anxiety. For some people, success can cause negative impacts such as distraction or paranoia (Kluth 2011).

Success, like failure, presents its own set of challenges. The renowned playwright Tennessee Williams experienced this firsthand when he found himself overwhelmed by the success of his play “The Glass Menagerie”, describing the security derived from it as both “a catastrophe” and “a kind of death” (Williams 2011), as it simultaneously removed the drive and desire to be successful, while also increasing the pressure of expectation from others who demanded that success to be continued. This sentiment is echoed by various individuals across different fields, including athletes, scientists, generals, entrepreneurs, performers, lottery winners, and politicians (Kluth 2011).

Anxiety surrounding success often stems from a lack of understanding of its origins and replicability. Doyle (1989) reported that many small businesses faltered after initial success due to a failure to comprehend the reasons behind their success and therefore how to sustain it. Indeed, success can be a double-edged sword as while it can lead to prosperity and influence, it can also strain relationships and erode trust. Success can therefore be both a blessing and a burden, with its advantages often accompanied by unforeseen challenges.

This paper reports on a research study that examined the dynamics of the perceptions of success as they relate to future university students from the population group defined as Gen Z. This research sought to discover if this group of future potential students had a different interpretation of success, and if so, if it could be distilled in such a way that universities could learn from this understanding and so adapt their branding, marketing, and educational delivery to reflect this new thinking and set of expectations.

3. Materials and Methods

This study was qualitative in nature and took the philosophical position of interpretivism, with an inductive approach, to allow the patterns and trends within the data to emerge (Bell et al. 2022). Interview questions were developed based upon an understanding of the phenomena being investigated, as detailed by O’Sullivan (2022), and were designed specifically to unlock the thoughts, views, beliefs and feelings of participants. Interview questions were informed by the literature review findings and were based around the following topic areas:

- Definitions of success;

- Variables of success;

- Examples of success;

- Feelings associated with success;

- Recognition derived from success;

- Interpretation of success.

The data were collected using semi-structured interviews and represent the personal perceptions and feelings of the participants involved in this study (Saunders et al. 2019). As such, the data are subjective in nature.

While semi-structured interviews can provide a degree of flexibility in terms of both delivery and depth, they can also be prone to the introduction of researcher bias as the thoughts, feelings, and experiences of the interviewer may impact upon how they deliver the agreed upon questions. As a result, the data collected, and the understanding derived from the data, can become skewed (Saunders et al. 2019). Furthermore, the level of probing undertaken with each participant, and/or the participant’s degree of comfortableness with the process, may vary considerably, thereby introducing further inconsistencies. To overcome these factors, qualitative researchers ignore the detail and look instead at the overarching patterns and trends revealed (Bell et al. 2022). While generalization is therefore quite limited, the insights provided are valuable in terms of understanding the broad contexts at play and the resulting implications.

The time horizon for this study was cross-sectional, as it formed a snapshot of participant perceptions at a single point in time. Participants in this study were students undertaking their level six (final undergraduate year) business management or marketing degrees at three different case study post-1992 universities in the UK. Specifically, all three case study universities were located in England, which has a different educational system to Scotland, Wales, or Northern Ireland. A purposive sampling technique was applied to ensure that participants included in this study would have a range of interesting and relevant perspectives to share. The sample was based exclusively upon UK final year undergraduate business, management, or marketing students attending one of three case study universities, and it included a mixture of males and females. All participants were within the Generation Z age category. Further details regarding the sampling process applied can be accessed in the work of O’Sullivan (2022).

Participation was on a voluntary basis and the data collected were recorded for accuracy, transcribed for analysis, and then anonymized (Table 1) to protect the identity of those involved. Each participant was provided with an information sheet prior to their involvement to ensure that they understood the process, risks, and purpose of this research study. Interviews were undertaken face to face at a time and location selected by each participant to ensure that they were comfortable with the interview setting. Together, these factors support the trustworthiness and validity of the data collected in terms of credibility, confirmability, and dependability (Lincoln and Guba 1988).

Table 1.

Participants in this study.

In accordance with ethical constraints, the analysis of each interview transcript was not undertaken until the relevant student had completed their course, and the researcher undertaking the analysis was not part of the teaching team for any of their final year modules.

The analysis itself was undertaken manually, which is the approach supported by Robson (2011), and the recursive abstraction method was applied (Polkinghorne and Taylor 2019). This is a six-step process designed to distill and collapse data in a series of repeated iterative cycles involving paraphrasing the original data, grouping the paraphrased data into themes, identifying appropriate codes within those themes, and then collapsing the codes repeatedly to reveal the emerging patterns and trends (Polkinghorne and Taylor 2021), which represent the final themes that emerge. Because of the nature of this process, and the recoding of the steps undertaken, it is both rigorous and repeatable (Polkinghorne et al. 2023). Examples of this approach being used for similar studies include by Stewart et al. (2023) and Shahid et al. (2023).

This research was undertaken with ethical approval from Bournemouth University (reference 14265).

4. Findings

From the recursive abstraction data analysis undertaken, the following five clearly defined themes emerged (Table 2), which will each now be considered in turn, with quotes from participants as illustrative examples:

Table 2.

Summary of participant responses.

- Being objective and task-driven;

- Embracing fluidity and subjectivity;

- Being ethically and morally responsible;

- Having resilience;

- Accepting and learning from failure.

4.1. Theme 1—Being Objective and Task-Driven

The data demonstrated success to be both objective and task-driven and that a fundamental characteristic of success is to be driven and motivated to triumph:

“If you set a particular objective, and you achieve that objective, or succeed it, then that is success.”(Participant C3S3)

“Have a sense of purpose, be objective based, and have a need to be driven, to want to achieve success.”(Participant C1S2)

It was recognized that while success flows between both professional and personal lives, achieving success in either context is emotional and related to how the participant felt about the result:

“Meeting these aims and making sure you are happy with the outcome.”(Participant C2S3)

The data also demonstrated many different drivers for objectives and tasks depending upon the overall goal. It was suggested that objectives and tasks can be very subjective and certainly be something considered at a personal level:

“One needs to decide for yourself. You’ve got to have an understanding of what success actually looks like to you.”(Participant C3S2)

The concept of having a sense of purpose, and a feeling of aspiration, were interplayed frequently. Examples of aspiration included a wide range of examples including feelings, locations, and achievements.

“Personal, domestic and emotional success [are often] integrated into your employment work aspirations.”(Participant C1S2)

Interviewees felt that these objectives needed to be considered and confirmed, put into place, and then worked toward as aspirations. All participants proposed that a fundamental consequence of success is achieving what you set out to achieve. This was presented as almost a defining term of success. It was felt that achieving something perceived to be “against the odds” makes the experience a surprise not only for the individual, but also for others around them.

“It’s a nice feeling when I can surprise people that I have achieved something they didn’t think I could.”(Participant C1S1)

Furthermore, it was highlighted that achieving what you set out to can also change your perception of your own character and ability.

“I’ve always thought of myself as being quite a quiet, shy person, and my success has made me realize that I’m not actually. It’s made me realize there is a lot [more that] I can achieve.”(Participant C1S2)

“Success also made me have increased confidence in my ability.”(Participant C1S3)

Achieving goals and objectives made interviewees feel good about themselves and take pride in their ability. This feeling of confidence was also reported as flowing into their wider personal lives.

“Achieving success in my career has impacted my confidence level in my personal life. It’s pushed me outside of my comfort zone. It has made me grow and be more confident.”(Participant C1S2)

While participants recognized that “luck” can impact upon success, it was not recognized as being an integral part, and the achievement of planned objectives superseded the randomness of luck.

“Luck happens in lots of areas that can contribute to success. Intrinsically, I don’t see [luck] as being part of the definition of success. [Luck] is not a significant contributor to success or failure.”(Participant C3S3)

Maintaining control of a situation was deemed important when being successful, and so luck should not be considered an antecedent of success, as the randomness created cannot be controlled.

“If success happens when you have no control whatsoever, it means that you haven’t done anything in that particular context to make it happen, because success is worked for.”(Participant C3S3)

4.2. Theme 2—Embracing Fluidity and Subjectivity

The research undertaken revealed that while the goals of success may change over a lifetime, the emotional feelings and euphoric response to achieving success remain more constant. Equally, the process of achieving success may be changeable and fluid too, and so individuals need to be able to accommodate such changes in terms of how they seek to achieve success and also how they know when they have been successful. Flexibility and adaptability are therefore required as the definition of success evolves with time.

“As things evolve, timescales may adjust. It’s a very fluid concept that changes, dependent on the context.”(Participant C2S1)

“A broad determinant for success therefore is the ability to reframe, be flexible, and view things differently along the way.”(Participant C2S2)

Participants agreed that the shape and definition of success often change from less tangible to more emotional outcomes. Interestingly, there appear to be a variety of different timeframes that can be applied to this change.

“When you’re younger you think about success as being money and based on what other people think. But when you get older, it’s more based on how you feel about yourself. And if you believe that money defines your success or not.”(Participant C1S1)

Participant C3S2 endorsed this by suggesting that in a younger life, success was more about material items. The data demonstrated a timeline, in that as time passes and one gets older, a shift happens and success tends to become more important at a personal level, and less about meeting the expectations of others. For many, success is therefore more about a sense of personal satisfaction. Furthermore, it was suggested that as this shift happens, the consequences of success may become easier to achieve due to expectations and demands on our lives easing as we grow older.

Participants described the entirely subjective nature of success. It was felt that only once you understand what success means to you as an individual, can you go on to put the steps in place to achieve a successful outcome.

“I think it’s all about how you feel about yourself. If you think you’ve done a good enough job, or if you think you could have done better.”(Participant C1S1)

Accepting the “small wins” was deemed as being important because defining success using very specific terms and relying on metrics is a route to disappointment when things do not turn out exactly as planned. The research indicated that a shift in our perceptions of success changes with our life journey and is mirrored with how we judge others’ success. In fact, the research showed there are many variables for achieving happiness and many different measurables. It was noted that academic success, money, or career development and seniority do not always result in an individual being happy, although others may use such achievements to benchmark themselves and so conclude that they are less successful in comparison.

The interpretation of success is also impacted by the context of achieving success. Participants recognized that success will be very different for individuals, depending on whether it is personal or professional success they are seeking. For example, success may be in a very commercial and superficial context as opposed to success in a socially rewarding enterprise. Furthermore, participants suggested that individuals need to be realistic about what success is for a given context. For example, making lots of money in a promising business context might be considered to be a success, but not losing money in a difficult and dynamic business context, in which resources are limited and commercially pressured at extreme levels, might actually be considered by many to be a bigger achievement.

“There needs to be compromise. [An outcome] might not actually be what you initially wanted, but it might still be a success.”(Participant C3S2)

4.3. Theme 3—Being Ethically and Morally Responsible

The data demonstrated that the way we view the shape of success can often be influenced by several factors, including our own individual philosophy and personal values. Demonstrating good morals, and standing by your values, was considered by many to be a consistent requirement for success. Interestingly, the proposition that upbringing may influence our core values Participant C2S1 was also floated, including in the following example:

“Being raised in a working-class family influenced my philosophy and outlook.”(Participant C2S1)

Together, such examples articulate success to be a complex and rounded construct, but ultimately one that is about people achieving what they want, and in a way that they want to achieve it, which may be why luck, as described in Theme 1, was not valued in terms of success as much as it might have been expected to be.

Witnessing people achieving success by demonstrating strong values and ethical commitment was considered motivating for others to do the same. Furthermore, it was recognized that a person’s circumstances can change throughout a lifetime, and such changes could be positive or negative. It was felt that this change in circumstances might impact upon how success is viewed, and in doing so, it might trigger a change.

“[A] significant shift in someone’s perception of what they think is important and therefore then how they define their own success.”(Participant C2S3)

The data revealed that peer recognition of success will vary depending on how ethically success was achieved, as it depends on the role the person or organization played in achieving said success. While the data demonstrated respect to be a consequence of success, participants were firm believers that success should be achieved ethically and morally in order to attract peer respect, and that the way success is achieved will also impact upon the level of recognition and respect encountered as a result.

“Those people that do achieve success through being trustworthy, authentic and empathetic, have a lot more respect for their successes.”(Participant C1S1)

“(It’s not about bragging about my success, it’s the feeling, the sharing that kind of experience and having people I know be proud of me.”(Participant C2S1)

Being acknowledged as a role model for others was considered a consequence of success, since role models can demonstrate what is achievable, but furthermore, role models should act as examples of encouragement and offer inspiration around ethical and sustainability issues, thereby making a positive impact to wider society.

4.4. Theme 4—Having Resilience

The data collected revealed that that the path to success can require considerable resilience due to the need to consistently overcome adversity and barriers. Influencing factors such as background, education, class, opportunity, and health were suggested in the data as potential barriers to success.

“You need to have a straight measurement of your success. Where you were, where you are now, and what you did to get there.”(Participant C2S3)

The data suggested that it is inevitable that both organizations and individuals will encounter challenges and undergo difficult periods. Accordingly, the notion of resilience was presented as an integral quality required not only to tolerate and overcome adverse conditions and situations, but to emerge stronger from them. The data presented resilience as being a willingness to change processes, and/or focus, in order to overcome a problem presented by the external environment. It is about accepting that the specific solution in question did not work but having strong enough beliefs in the direction of travel to try again in a different way. The data demonstrated that sometimes being resilient can also mean looking inward to evaluate our own behavior and possibly to identify the need to change.

“Change our own behavior to enable success.”(Participant C1S2)

“Your behavior influences how successful you are.”(Participant C2S1)

Participants noted this can be emotionally challenging and sometimes difficult to accept, but an important element to resilience. Furthermore, the data suggested that barriers can vary, but in the process of overcoming them, there are always levels of resilience, commitment, and motivation that need to be considered.

“Overcoming barriers to success is a reflection of a sustained effort; it can’t [just] happen overnight.”(Participant C2S1)

The data indicated the resilience required to achieve success often supports the drive for success and may in fact make it more focused. Participants felt that the more barriers there are on the way to success, the greater the achievement.

“If I know how hard they have worked to get there, and the barriers they have had to face, I think their success particularity stands out.”(Participant C2S1)

The data demonstrated that the quest for success is reliant on being sustained and planning, which often involves a tremendously high level of commitment and dedication. Moreover, often, success comes at the cost of compromising other aspects of life and certainly involves juggling a lot of different roles. The need to make personal sacrifices on the journey to success was recognized by many as being unavoidable.

4.5. Theme 5—Accepting and Learning from Failure

The data defined failure as occurring when a set objective is not achieved. While failure was clearly recognized as an experience that can dampen spirits, it was nevertheless also considered to be an inevitable part of achieving success, and witnessing failure often helped in the subsequent journey to a successful conclusion.

“You have to experienced failure in order to fully-appreciate success.”(Participant C1S3)

Participants reported that they considered failure to be an inevitable part of the journey to success. Furthermore, they commented that failure is often a two-step process (1) to identify the failures and then (2) to learn from them and make changes to minimize future failures.

“It’s the classic saying, you learn more things from failure than you do success, and you can’t expect to succeed first time round.”(Participant C3S3)

“Taking a step back, and questioning where it went wrong, enables us to change our behaviors.”(Participant C2S2)

“[I try to] stop and reflect and think where did I go wrong, or why did that not work.”(Participant C1S2)

However, understanding failure and learning from it was deemed to be fundamental, as learning from failed attempts encourages determination for future success. Being open-minded to new approaches was also deemed crucial. Additionally, it was suggested that extra respect can be gained if failure has been involved on the way to success, if the success was not anticipated. It was observed that success often depends up on bravery and risk-taking and that failed attempts can attract respect from stakeholders for these reasons.

The concept of feeling shame after a failed attempt was largely considered to be an outdated concept now, as demonstrated by the following participant statement:

“To learn from failure, and then to consider how you are going to change it, or how it changes you as a person, is crucial in order to be successful. Ultimately, you need to understand how you must adapt to the understanding of failure.”(Participant C3S3)

Respondents also felt that failure can strengthen resolve, paving the way to overcoming future hurdles. If everything is always easy, and success seemingly straightforward, then the first instance of failure can lead to a crisis of confidence, where previously held beliefs can be abandoned quickly in the scrabble for success. However, if failure has been experienced and embraced in the past, it provides a broader skillset for the individuals and/or organizations to work around the challenges. It can also make any subsequent success feel like an even bigger achievement. In this way, the success gained has been truly earned.

Unpacking and reflecting on failure were re-appearing themes due to potentially needing to change behavior in order to succeed. Not only did participants regard failure as necessary in the journey to success, but also, it was felt that the more failures experienced, the greater the feeling of reward when success is ultimately achieved.

“[Failure] makes the feeling of success even more euphoric as it feels more of an achievement.”(Participant C1S1)

5. Discussion

Fundamentally, this research echoes the wider literature findings (John and De Villiers 2022), emphasizing the need to understand what success means to an individual, as the concept of success varies significantly from person to person, which is a concept supported by the findings of Mourad et al. (2020).

There were multiple variables identified by the research sample for defining the concept of success. Participants reinforced the literature, identifying success to be broadly understood as the realization of an aim or activity directed toward its fulfillment, which supports the findings of Baczko-Dombi and Wysmułek (2015). The notion of success being entirely subjective was a common observation throughout the data. The data also presented success to be a task-driven activity which requires commitment and motivation for working toward a goal. This reinforces the findings from Korda (1977). Furthermore, the data supported the assertion that success is earned and that there is not any entitlement to it (Gladwell 2008).

Interviewees expressed that the concept of success is multifaceted and varies greatly among individuals due to differing understandings. Both the data and literature confirmed that success is a complex concept that undergoes change and evolution throughout the lifetime of an individual. Research undertaken by Xiao et al. (2023), and also by Eldegwy et al. (2023), considered university brands and identified complementary findings that supported the need to contest for students in an increasingly global marketplace. Furthermore, our perception of success is frequently influenced by our upbringing. Variables such as culture and the environment were identified as influential factors in shaping and impacting our views on success (Iashnova 2004). This again reinforces Gladwell (2008), who suggested that gender and education, as well as physical and emotional support from family, are important internal factors affecting success.

The analysis of the data illustrated success as a multifaceted and intricate concept, with autonomy and personal ownership being pivotal aspects. Participants emphasized the importance of feeling a sense of ownership over their own success, stating that it is fundamentally necessary to perceive it as being their own achievement. This aligns with recent studies on self-determination, which suggested that autonomy is crucial for individual wellbeing and intrinsic motivation (Ryan and Deci 2017). Additionally, participants highlighted resilience as a crucial factor contributing to success, reflecting contemporary research that identified resilience as being key to overcoming adversity and maintaining goal-directed behavior (Fletcher and Sarkar 2013).

Moreover, it was suggested that overcoming life’s obstacles to achieve success merits additional recognition and admiration. Participants observed that upbringing often shapes individuals’ exposure to opportunities, thereby influencing their potential for success. This echoes the sentiments of scholars such Gladwell (2008), who proposed that an individual’s success can stem from the gradual accumulation of advantages, including factors such as their birthplace, their parents’ occupations, and the circumstances of their upbringing. It also resonates with current perspectives on social capital, which emphasize that family background and early life experiences play a significant role in determining future success (Apfeld et al. 2022).

Subjectivity was deemed a fundamental characteristic of success by the participants. Consistent with the literature, they recognized that the shape of success changes during a lifetime, as well as expectations for success also evolving with age and circumstances. Research by Bostock (2014) supports this view, highlighting how success is interpreted differently across different life stages and is influenced by personal goals and social contexts. As expected, participants noted various interpretations of the rewards of success, including financially tangible rewards such luxury cars, holidays, and properties. However, more interesting was the recognition of emotional gratification such as happiness, positive wellbeing, and making a difference to something or someone. This is consistent with the finding that emotional and psychological fulfillment often outweigh material success in terms of life satisfaction (Steger et al. 2021).

Feeling a sense of happiness was deemed a clear reward of success, but participants focused also on experiencing a sense of pride. They noted that sometimes the reward of success is experiencing a sense of relief. This was tied in specifically with achieving milestones during their degree studies, which reinforces comments that success to them was inked to being task-driven. Recent studies on goal setting have demonstrated that task achievement fosters both pride and relief, particularly in academic contexts (Moeller et al. 2012; Martin and Collie 2016).

Peer perception of success was considered to be a key driver, along with experiences of feeling safe and secure within a family environment. Experiencing a sense of wellbeing were also commented on frequently by all participants. In fact, all interviewees suggested that impacting society, contributing to a greater good, and leaving a legacy for change were key consequences of success. This view aligns with research that highlighted how modern definitions of success increasingly include social responsibility and societal contributions (Jackson and Bridgstock 2018; Arroyave et al. 2021). Furthermore, participants articulated the importance of a sense of belonging as being an integral experience that plays a pivotal role within the concept of success, mirroring contemporary discussions about the role of social connectedness in achieving personal and professional success (Yatczak et al. 2021).

However, participants also noted that success was not always positive, and many shared the view that success is inherently competitive and can intensify with repeated experiences of achievement. Data collected revealed that success often involves comparing our achievements with those of our peers, which aligns to the research undertaken by Matthews and Kelemen (2024). However, the degree to which we engage in this comparison may often be significantly influenced by our background, and that background, including cultural factors, can play a role in shaping our perceptions of success itself (Markus and Kitayama 2014). As a result, there may be a discrepancy between societal expectations and personal motivations, leading people and organizations to pursue success in a manner incongruent with their own values and aspirations (Abdolrezapour et al. 2023). Consequently, achieving success in accordance with societal norms can leave a feeling of lack of fulfillment, despite external recognition of accomplishments (Andersson et al. 2019).

Interviewees further discussed the negative connotations associated with success. They provided examples from people’s lives in which achieving their goals left them feeling unfulfilled or lacking challenge, leading to a sense of boredom. Additionally, the journey to success was acknowledged as requiring compromise and personal sacrifice, often resulting in reduced social interaction, limited time with loved ones, and ultimately, burnout. Together, these factors can detrimentally impact upon mental wellbeing. Interestingly, this disconnect between perceived success and actual fulfillment was primarily observed in the context of professional success (Baumeister et al. 2016). Participants noted that individuals were more likely to misinterpret success when it was linked to money or professional status, only to realize that these factors did not always bring happiness. Conversely, there was no mention in the data of individuals achieving emotional or spiritual success in a personal context.

The data suggested that worthwhile success cannot be achieved in a short time because it can take a long time to establish and evolve, and then it needs to be evaluated over time.

“The vision between short term, and long term, is relevant for the individual or brand, as success is a long-term evaluation of your achievements over time.”(Participant C3S1)

Interviewees felt that this long-term focus demonstrates more resilience, and that it is important to build upon the long term because it was recognized that being resilient takes courage and can be difficult to achieve.

However, it was also suggested that while success is synonymous with longevity, it was felt that too much focus on the short term can lead to failure. Participants provided examples from their studies of needing to be determined to meet academic pressures such as deadlines and exam anxiety. They also reflected on times when they needed to develop their determination to receive challenging feedback on assignments, or even failing a unit through unsatisfactory performance.“You have strength, but the great difficulty is being able to cultivate that and to be resilient and to make these big strides.”(Participant C3S2)

Participants linked demonstrating competitiveness and resilience together, suggesting that success is a competitive concept that can push you to outperform others around you.

“For many it is about trying to do better than the people I’m comparing myself against.”(Participant C3S1)

When instances of underachievement happen, it was recognized that they can demand resilience to “take stock and brush yourself off”. Personal goal setting, and then making comparisons, was noted during data collection. Interviewees suggested that the nature of success is to be competitive by constantly pushing yourself to perform better.

Success in this sense can therefore instill a sense of endless challenge, which demands great resilience. Participants also reflected that a competitive streak experienced during the journey of success can be triggered by how our peers view us.“Once you achieve success it goes further and further. I feel like success has to do with the resetting of goals. So, once you achieve a goal, and you have success with that goal, you set another to have a new success.”(Participant C3S3)

“Often if people see you achieving your goals, they will see you as being successful.”(Participant C3S2)

Whatever the situation, all participants reflected that building and maintaining resilience is a fundamental skill needed for achieving success in any context. The research demonstrated that resilience in this context is when a person or organization is so committed not only to the end goal, but also the tactics that they are employing to overcome obstacles. To persevere with an activity when it does not look likely to lead to success requires commitment to both the end goal, and to the methods being used to get there. It can be a challenging experience, as it involves not abandoning those principles, but instead trying to change and/or remove the barriers to the goal being achieved. Inevitably, this often involves considerable personal sacrifice.

This resilience is essential for overcoming both personal and social barriers, such as discrimination, and can lead to broader societal impact and legacy-building, as observed in historical and contemporary examples of social change (Dawson and Daniel 2010). It can contribute to one of the broader elements of success identified elsewhere in the research—that of contributing to an impactful legacy. By changing the external environment to remove an obstacle, it is highly likely that resilience can pave the way for others to build upon the same success, leading to huge advances in society. The success of one person can lead to the success of others who follow in their footsteps. Examples from history found in the data include women securing the right to vote and the end of apartheid in South Africa. Such achievements were only made through individuals with extreme resilience, but their ultimate success is considered all the greater for the difficult path to achieving them.

The research suggested that failure is an inevitable component of success even if it ultimately leads to abandoning an approach altogether. Recent studies have emphasized that learning from failure is integral to future success, as it fosters resilience and adaptability (Illouz 2020). We can only learn something does not work at all if we try it, and even in that seemingly “ultimate” failure in which an undertaking is abandoned, there will still be principles that can be applied to inform future ventures in seemingly different sectors and/or applications. Failure, like success, is largely transferable. While success may occasionally be instantaneous and “easy”, such a pattern is unlikely to be repeated in an individual’s career, or in the story of a brand. Instead, success is almost always borne from what is learned in failed attempts. Even an “immediate” success in one arena is usually the result of failures elsewhere, with the learnings transferred into the new different context. This can best be accomplished by throwing off the historical shackles of shame associated with failure, and instead of seeing it as the end of a journey, viewing it as being a step along the way to future success. This shift in perception, viewing failure as a step toward success rather than a final endpoint, is increasingly recognized in both personal and professional domains (Ronnie and Philip 2021).

The data indicated the existence of both traditional and contemporary interpretations regarding the nature of success. Traditionally, success has been associated with concepts such as reputation, wealth, and power, reflecting outcomes that are highly valued in society. However, a shift has occurred in recent times, wherein the focus of success has transitioned toward notions of giving back to society and being a corporate citizen. This evolution in perspectives emphasizes the importance of the impact that individuals have on their surroundings, and on the legacy that they leave behind, which are both fundamental aspects of achieving success. Interviewees recognized the significance of making a positive contribution to society, highlighting the notion that success should be utilized for the greater good.

Over time, the criteria for assessing success have undergone a transformation, with religious considerations gradually giving way to more secular notions centered around mindfulness and societal awareness. Success is no longer solely perceived as a reward in the afterlife, but it is instead evaluated based on the enduring impact individuals have on their immediate environment and future generations. This shift underscores the importance of contributing to the greater good and leaving behind a meaningful legacy. Success is now characterized by the tangible benefits it brings to society, whether through problem-solving, job creation, or fostering social entrepreneurship to uplift marginalized groups. Furthermore, success is viewed as being a long-term endeavor, measured not just in immediate gains, but also in the enduring legacy that transcends generations. It is imperative that success be sustainable, and capable of being carried forward by future generations, ensuring its true societal impact and leaving a legacy for others to build upon.

The findings obtained from this study regarding Gen Z’s perspective on success (Figure 1), coupled with the varied viewpoints on the concept of success itself, can now be utilized to enhance the understanding and appreciation of success within a brand context. By examining interpretations of success in broader terms, these overarching findings can then be extrapolated and applied to brands and branding.

Figure 1.

Framework indicating Gen Z’s interpretation of success.

Taking these results into account, this research can inform the branding strategies of universities in several ways. For example, to satisfy the need to be driven by objectives and tasks, universities should define clear objectives and communicate them to students effectively. This will enable prospective students to identify and understand specific goals that they can achieve through their education. Marketing materials that highlight how previous students have achieved their goals and reflecting upon the resulting feelings of accomplishment will help to motivate prospective students. However, it is also important that success is recognized as being a subjective accomplishment, so these examples should be broad in scope, catering to different aspirations and career goals. They must also be authentic. This was clear from other studies as well including the work of universities in needing to promote flexibility in their courses so that students can see how their learning can be adapted to meet changing career goals and life circumstances. Instead of promoting a degree as little more than a training course for a specific career, universities should emphasize that the concept of success can evolve over time, and education can provide students with the flexibility to adapt to new circumstances and opportunities. Case studies should include graduates who went into unexpected careers or found new passions as a result of their time at university.

Given that for Gen Z, being ethically and morally responsible is an important factor, universities should emphasize their commitment to ethical practices and moral integrity to maximize their appeal to students who value ethics. Academics and graduates who have achieved ethical success should be celebrated to provide inspiration. Universities should also demonstrate external validation of their own ethical approach to demonstrate institutional behavior that matches these beliefs. For example, achievements recognized by such companies as Fairtrade, Athena Swan, Investors in People, and QS World University Rankings for Sustainability should indicate that the university operates ethically and responsibly as an organization.

Success is not a linear process, and pitfalls and setbacks are inevitable and indeed form a crucial part of the learning from which success is often born. Universities should therefore not shy away from sharing stories about students who overcome difficult situations through fear of putting off prospective students. Instead, such stories should be seen as an opportunity to inspire and reassure prospective students, and to highlight university support systems, and in doing so, it can be demonstrated how help will be available when required in the form of counselling, mentorship, and academic support. Equally, education should be presented as a long-term investment for the future, and that the resilience that Gen Z value is needed to reap the enduring benefits it will bring.

Universities should also encourage a growth mindset by demonstrating that they foster an environment in which failure is seen as an opportunity to learn. This can be achieved through testimonials and case studies and using academics and students as examples that provide insight and inspiration to others. Failure should be positioned as an inevitable part of innovation, and universities need to find ways of highlighting that they offer a supportive environment that helps students to reflect upon, and learn from, the failures that may occur, as it is from these lessons that they can ultimately succeed.

6. Conclusions

The core contribution of this research sought to gain an insight into interpretations and implications of the concept of success from a sample of final year undergraduate students in the context of a selection of comparable case study UK universities. The research unpacked how Gen Z perceive achievement. This is an essential activity for the modern-day university to explore, and understand, in order to project an aligned brand, and furthermore, effectively engage with its key demographic of future students. By recognizing Gen Z’s preferences and aspirations, institutions can tailor their branding, educational portfolio, and overall campus experiences to ensure that they resonate fully. By authentically embodying the key variables of success within their brand, universities may be able to enhance their offering and increase their appeal among Gen Z, ultimately fostering and embracing a stronger sense of connection, loyalty, and belonging within the university community.

6.1. A Vision for the Future of University Branding

The concept of success is a construct built on shifting sands; therefore, it is essential to unpack perceptions of what success means to key stakeholders in modern-day higher education, to appropriately align expectations with delivery. Enabling universities to deliver the appropriate skills for students to improve their employment opportunities will help to ensure that students can achieve their goals.

The research illustrates that Gen Z, and their viewpoints, are intricate and nuanced. Their opinions and perceptions are subject to change over time and can be influenced by external factors and cultural dynamics. Moreover, individuals’ tastes and preferences evolve and develop. The research highlights that Gen Z has distinct definitions of success compared to previous generations. While traditional markers of success, such as wealth and prestige, still hold some importance, the data indicated that Gen Z students often prioritize other factors such as personal fulfillment, social impact, and work–life balance. They seek careers that align with their passions and values, placing an emphasis on meaningful experiences over material gain. Therefore, universities need to recognize and cater to these evolving definitions of success to effectively engage with Gen Z students.

Moreover, this research suggests Gen Z students value authenticity and transparency from universities. They are adept at detecting insincerity and are more likely to support organizations that demonstrate genuine concern for social and environmental issues. Universities that authentically align their branding with values such as diversity, sustainability, and social responsibility are more likely to resonate with Gen Z students.

By understanding and embodying these values, universities will be able to cultivate a strong sense of trust and loyalty among Gen Z students, enhancing their own brand reputation and appeal in the process, and thereby attracting more students who align to these ideals. The authors therefore strongly urge universities to consider the recommendations of this paper relating to actions that they can be undertaking now, which will maximize the attractiveness of their educational offerings to prospective Gen Z students.

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

This investigation focused on three post-1992 universities in England, constituting a multiple case study approach. The outcomes offer insights into potential trends by employing recursive abstraction as the analytical method for data comprehension. However, it is essential to note that these patterns should not be conclusively regarded as being transferable, and caution is advised when extending them to other dissimilar universities, due to the restricted sample size and cultural specificity related to English post-1992 universities. Hence, the authors recommend further exploration to ascertain whether the conclusions drawn in this study can be replicated in a broader investigation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.O.; methodology, H.O.; formal analysis, H.O. and M.P.; investigation, H.O.; data curation, H.O.; writing—original draft preparation, H.O.; writing—review and editing, H.O., M.P. and M.O.; supervision, M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Bournemouth University (Approval Reference No. 14265 on 31 October 2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Until such a time as the data become publicly available, any requests to access the datasets used in this study should be directed to the corresponding author and will be considered on an individual basis. For more information regarding the PhD research project that formed the basis for this paper, please visit: https://eprints.bournemouth.ac.uk/37482/ accessed on 12 October 2024.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the readability of Table 1. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

References

- Abdolrezapour, Parisa, Sahar Jahanbakhsh Ganjeh, and Nasim Ghanbari. 2023. Self-efficacy and resilience as predictors of students’ academic motivation in online education. PLoS ONE 18: e0285984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albreght, Karl. 2006. Social Intelligence: The New Science of Success. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, Thomas, Mikael Cäker, Stefan Tengblad, and Mkael Wickelgren. 2019. Building traits for organizational resilience through balancing organizational structures. Scandinavian Journal of Management 35: 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apfeld, Brendan, Emanuel Coman, John Gerring, and Stephen Jessee. 2022. Education and social capital. Journal of Experimental Political Science 9: 162–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyave, Fabio, Ana Redondo, and Angels Dasí. 2021. Student commitment to social responsibility: Systematic literature review, conceptual model, and instrument. Intangible Capital 17: 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baczko-Dombi, Anna, and Ilona Wysmułek. 2015. Determinants of success in public opinion in Poland: Factors, directions and dynamics of change. Polish Sociological Review 191: 277–93. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, Roy, Kathleen Vohs, Jennifer Aaker, and Emily Garbinsky. 2016. Some key differences between a happy life and a meaningful life. In Positive Psychology in Search for Meaning. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Emma, Alan Bryman, and Bill Harley. 2022. Business Research Methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bostock, Jo. 2014. The Meaning of Success. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chapleo, Chris, and Helen O’Sullivan. 2017. Contemporary thought in Higher Education marketing. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education 27: 159–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Shu-Ching. 2022. University branding: Student experience, value perception, and consumption journey. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, Amy, and Jed Rubenfeld. 2014. The Triple Package: How Three Unlikely Traits Explain the Rise and Fall of Cultural Groups in America. New York: Penguin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coombs, Harriet. 2021. First-in-Family Students. Report 146. Oxford: Higher Education Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Criollo-C, Santiago, Andrea Guerrero-Arias, Ángel Jaramillo-Alcázar, and Sergio Luján-Mora. 2021. Mobile learning technologies for education: Benefits and pending issues. Applied Sciences 11: 4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, Patrick, and Lisa Daniel. 2010. Understanding social innovation: A provisional framework. International Journal of Technology Management 51: 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolot, Anna. 2018. The characteristics of Generation Z. E-Mentor 74: 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, Peter. 1989. Building successful brands: The strategic options. Journal of Marketing Management 5: 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldegwy, Ahmed, Tamar Elsharnouby, and Wael Kortam. 2023. Blue blood students of occupational dynasties and their university choice: The moderating role of parent–child occupational following. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, David, and Mustafa Sarkar. 2013. Psychological resilience: A review and critique of definitions, concepts, and theory. European Psychologist 18: 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiana, Marieti, Andre Rahmanto, and Ign Satyawan. 2023. International branding of higher education institutions towards world-class universities: Literature study in 2017–2022. Journal of Social and Political Sciences 6: 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaubert, Cécile, and Evra Louvet. 2021. Wealth, Power, Status: Role of Competence and System-Justifying Attitudes in the Rationalization of Social Disparities. Göttingen: Hogrefe Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Gladwell, Malcolm. 2008. Outliers: The Story of Success. New York: Little, Brown and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Goleman, Daniel. 1996. Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More than IQ. London: Arrow Books. [Google Scholar]

- Goleman, Daniel. 2007. Social Intelligence. London: Arrow Books. [Google Scholar]

- Haley, Aimee, Sintayehu Alemu, Zenawi Zerihun, and Liisa Uusimäki. 2022. Internationalisation through research collaboration. Educational Review 76: 675–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Timothy, Tonia Gray, Greg Downey, and Michael Singh. 2018. The Globalisation of Higher Education: Developing Internationalised Education Research and Practice. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Higher Education Statistics Agency. 2024. Higher Education Student Statistics: UK, 2022/23—Student Numbers and Characteristics. Available online: https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/students/whos-in-he (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Iashnova, O. 2004. New research on success in the teaching and upbringing of younger students. Russian Education & Society 46: 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Illouz, Eva. 2020. Resilience: The failure of success. In The Routledge International Handbook of Global Therapeutic Cultures. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Denise, and Ruth Bridgstock. 2018. Evidencing student success in the contemporary world-of-work: Renewing our thinking. Higher Education Research & Development 37: 984–98. [Google Scholar]

- John, Surej, and Rouxelle De Villiers. 2022. Factors affecting the success of marketing in higher education: A relationship marketing perspective. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kethüda, Önder. 2023. Positioning strategies and rankings in the HE: Congruence and contradictions. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education 33: 97–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Jashim, and Jane Hemsley-Brown. 2021. Student satisfaction: The role of expectations in mitigating the pain of paying fees. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education 34: 178–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluth, Andreas. 2011. Hannibal and Me: What History’s Greatest Military Strategist Can Teach Us about Success and Failure. New York: Riverhead Books. [Google Scholar]

- Korda, Michael. 1977. Success! New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Kuh, George, Jillian Kinzie, Jennifer Buckley, Brian Bridges, and John Hayek. 2006. What Matters to Student Success: A Review of the Literature. Washington, DC: National Postsecondary Education Cooperative. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Jenny, and Bjørn Stensaker. 2021. Research on internationalisation and globalisation in Higher Education—Reflections on historical paths, current perspectives and future possibilities. European Journal of Education 56: 157–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Kam-Fong, Chin-Siang Ang, and Genevieve Dipolog. 2019. My first year in the university: Students’ expectations, perceptions and experiences. Journal of Social Science Research 14: 3134–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Yvonna, and Egon Guba. 1988. Criteria for Assessing Naturalistic Inquiries as Reports. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans, LA, USA, April 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, Benji, and Jacqueline Thomas. 2022. Adoption of virtual reality technology in Higher Education: An evaluation of five teaching semesters in a purpose-designed laboratory. Education and Information Technologies 27: 1287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markus, Hazel, and Shinobu Kitayama. 2014. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. In College Student Development and Academic Life. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 264–93. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Andre, and Rebecca Collie. 2016. The role of teacher–student relationships in unlocking students’ academic potential: Exploring motivation, engagement, resilience, adaptability, goals, and instruction. In Handbook of Social Influences in School Contexts. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 158–77. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, Michael, and Thomas Kelemen. 2024. To compare is human: A review of social comparison theory in organizational settings. Journal of Management, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, Colin, ed. 2011. Cambridge Essential English Dictionary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mercer-Mapstone, Lucy, and Catherine Bovill. 2020. Equity and diversity in institutional approaches to student–staff partnership schemes in Higher Education. Studies in Higher Education 45: 2541–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, Robert. 1968. The Matthew Effect in Science—The Reward and Communication Systems of Science are Considered. Science 159: 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeller, Aleidine, Janine Theiler, and Chaorong Wu. 2012. Goal setting and student achievement: A longitudinal study. The Modern Language Journal 96: 153–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourad, Maha, Hakim Meshreki, and Samer Sarofim. 2020. Brand equity in higher education: Comparative analysis. Studies in Higher Education 45: 209–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, Ralf, and Rodney Turner. 2010. Leadership competency profiles of successful project managers. International Journal of Project Management 28: 437–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naheen, Fahmida, and Tama Elsharnouby. 2024. You are what you communicate: On the relationships among university brand personality, identification, student participation, and citizenship behaviour. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education 34: 368–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, Helen. 2022. Antecedents, Nature and Consequences of Brand Success in Comparable Newer Universities. Ph.D. thesis, Bournemouth University, Poole, UK. [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan, Helen, Martyn Polkinghorne, Chris Chapleo, and Fiona Cownie. 2024. Contemporary Branding Strategies for Higher Education. Encyclopedia 4: 1292–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, Cynthia, and Joseph Trainor. 2014. Millennial students and the flipped classroom. Journal of Business and Educational Leadership 5: 102–12. [Google Scholar]

- Polkinghorne, Martyn, and Julia Taylor. 2019. Switching on the BBC: Using Recursive Abstraction to Undertake a Narrative Inquiry Based Investigation into the BBC’s Early Strategic Business and Management Issues. London: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Polkinghorne, Martyn, and Julia Taylor. 2021. Recursive Abstraction Method for Analysing Qualitative Data. In Encyclopedia of Tourism Management and Marketing. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 636–83. [Google Scholar]

- Polkinghorne, Martyn, Gelareh Roushan, and Julia Taylor. 2017. Considering the marketing of Higher Education: The role of student learning gain as a potential indicator of teaching quality. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education 27: 213–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polkinghorne, Martyn, Milena Bobeva, and Sidra Shahid. 2023. Managing Sustainable Projects: Analyzing Qualitative Interview Data Using the Recursive Abstraction Method. London: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Race, Paul. 2019. The Lecturer’s Toolkit: A Practical Guide to Assessment, Learning and Teaching. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, Colin. 2011. Real World Research. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Ronnie, Janoff-Bulman, and Brickman Philip. 2021. Expectations and what people learn from failure. In Expectations and Actions. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 207–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, Richard, and Edward Deci. 2017. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness. London: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, Mark, Philip Lewis, and Adrian Thornhill. 2019. Research Methods for Business Students. London: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Schlesinger, Walesska, Amparo Cervera-Taulet, and Walter Wymer. 2023. The influence of university brand image, satisfaction, and university identification on alumni WOM intentions. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education 33: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemiller, Corey, and Meghan Grace. 2018. Generation Z: A Century in the Making. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Selwyn, Neil. 2010. Looking beyond learning: Notes towards the critical study of educational technology. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 26: 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, Sidra, Martyn Polkinghorne, and Milena Bobeva. 2023. Supporting educational projects in Pakistan: Operationalizing UN Sustainable Development Goal 4. In SDGs in the Asia and Pacific Region. Implementing the UN Sustainable Development Goals—Regional Perspectives. Cham: Springer, pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, Anjali. 2014. Challenges and issues of generation Z. IOSR Journal of Business and Management 16: 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Bee, Kim Lee, Chee Liew, and Muthaloo Subramaniam. 2023. The role of social media engagement in building relationship quality and brand performance in higher education marketing. International Journal of Educational Management 37: 417–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, Michael, Patricia Frazier, Shigehiro Oishi, and Matthew Kaler. 2021. The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology 53: 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, Natalie, Martyn Polkinghorne, and Camila Devis-Rozental. 2023. Implications of COVID-19 on researcher development: Achievements, challenges and opportunities. In Agile Learning Environments Amid Disruption: Evaluating Academic Innovations in Higher Education During COVID-19. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 173–88. [Google Scholar]

- Uusiautti, Satu. 2013. On the positive connection between success and happiness. International Journal of Research Studies in Psychology 3: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Waite, Maurice, ed. 2012. Paperback Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weatherton, Maryrose, and Elisabeth Schussler. 2021. Success for all? A call to re-examine how student success is defined in higher education. CBE—Life Sciences Education 20: es3.1–es3.13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Tennessee. 2011. The Glass Menagerie. New York: New Directions Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Woodard, Howard, Sonya Shepherd, Mindy Crain-Dorough, and Michael Richardson. 2011. The globalization of Higher Education through the lens of technology and accountability. Journal of Educational Technology 8: 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Yaping, Nguyen Huong, Nguyen Nam, Phan Quyet, Cao Khanh, and Dao Anh. 2023. University brand: A systematic literature review. Heliyon 9: 102972. [Google Scholar]

- Yatczak, Jane, Teresa Mortier, and Heather Silander. 2021. A study exploring student thriving in professional programs: Expanding our understanding of student success. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice 21: 91–104. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).