2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

The methodology used in the study on the entrepreneurial competencies of immigrant women in the Children’s Villages of the Lambayeque Region is characterized by a quantitative approach, with applied research and an explanatory pre-experimental scope, using a hypothetical inductive method.

The quantitative approach involves the collection and analysis of numerical data to identify patterns and relationships between variables, which is adequate to measure entrepreneurial competencies objectively and accurately. Applied research is oriented to the solution of specific practical problems, in this case to improve the entrepreneurial competencies of immigrant women in the Children’s Villages of the Lambayeque Region, providing useful information for the design of training and support programs.

The scope of the study is explanatory pre-experimental. This means that, although an experiment is conducted, there is no strict control group, which characterizes pre-experimental designs. The explanatory purpose of the study not only describes the entrepreneurial competencies but also seeks to explain the causal relationships between the different dimensions of these competencies and entrepreneurial success.

A hypothetical inductive method is used, which begins with the formulation of hypotheses based on previous observations and theories. From the data collected, the hypotheses are validated, allowing the construction of knowledge in an inductive manner. This method is suitable for exploratory and explanatory studies that seek to understand how and why certain phenomena occur.

A 55-question Likert scale was used, designed to measure nine dimensions of entrepreneurial competencies: search for opportunities and initiative, risk anticipation, persistence and confidence, self-demand and quality, search for support and information, search for control and excellence, purposefulness, compliance and responsibility, and foresight of the future. The measurement scale had 5 points, where 5 represented “always”, 4 “ almost always”, 3 “undecided”, 2 “almost never”, and 1 “never”.

Entrepreneurial competencies were classified into levels according to the score obtained: expert (80–100 points), advanced (50–79 points), intermediate (30–49 points), and basic (10–29 points). In addition, an observation sheet was used to measure women’s performance in entrepreneurial actions, complementing the Likert scale and providing qualitative data on entrepreneurial behavior in real situations.

The quantitative approach and the use of structured instruments allow an accurate and objective measurement of entrepreneurial competencies, facilitating statistical analysis and the identification of patterns and relationships. Applied research ensures that the findings have practical relevance, and the explanatory pre-experimental experimental design allows the exploration of causal relationships, although with limitations in generalization due to the lack of a rigorous control group. Finally, the hypothetical inductive method facilitates the construction of knowledge from empirical observations, in line with the objective of understanding and improving the entrepreneurial competencies of immigrant women in a specific context.

2.2. Data Collection

Data for this study were collected through an online survey, which was conducted over an 18-month period between 2021 and 2022. The surveys were directed to women entrepreneurs of Peruvian and Venezuelan nationality from the Children’s Village of the Lambayeque Region. The sample consisted of 79 women, 39 of Peruvian nationality (49.4%) and 40 of Venezuelan nationality (50.6%).

The profile of the participants was detailed according to their level of education and age. The ages were categorized into five groups: 20 to 24 years (6.3%), 25 to 29 years (19.0%), 30 to 34 years (16.5%), 35 to 39 years (24.1%), and over 40 years (34.2%); the diversity in age allows for a broad understanding of entrepreneurial competencies at different stages of life.

During the survey period, the women participated in workshops on Design Thinking, Model Canvas, customer service, pricing, and digital marketing.

The sample size was determined using the concept of “data saturation,” which refers to the point at which responses become repetitive and no new information is added as data collection continues. The researchers simultaneously performed the analysis and data collection to identify this saturation point.

Likewise, the sampling was intentional and was chosen because the participants were part of the SOS Children’s Villages canteens, a space dedicated to assisting children and women in vulnerable situations. This strategy provided efficient access to a group of Venezuelan and Peruvian immigrant women who shared similar experiences and needs. In addition, the availability of an existing database facilitated the identification and contact with participants, thus optimizing the research process.

The following specific criteria used in this study were essential to ensure the relevance and depth of the results: (a) Venezuelan and Peruvian immigrant women; (b) women who had attended the workshops of the SOS Children’s Villages of Lambayeque; (c) women who started a new business during the pandemic; (d) voluntary participation in the survey; and (e) full participation in the workshops. It was ensured that the sample was homogeneous and representative of a specific group with similar needs and experiences, which facilitated the understanding of the challenges and opportunities they face in the process of entrepreneurship in this research.

The online questionnaire consisted of four sections: (a) name of the research, objective of the study, anonymity of participants and confidentiality of responses; (b) questionnaire instructions; (c) personal profile of participants; (d) Likert scale questions with multiple response options (always, almost always, sometimes, almost never, never). The questionnaire used was the Predominant Entrepreneurial Skills Self-Assessment Questionnaire of the German Agency for Technical Cooperation en 2003.

The questions formulated in the Self-Assessment of Predominant Entrepreneurial Skills of the German Agency for Technical Cooperation surround nine skills including initiative in the search for opportunities, anticipation of risk, persistence and confidence, self-demand and quality in activities, search for support and information, search for control and excellence, proactivity, compliance and responsibility, and foresight of the future.

The semi-structured questionnaires were validated by experts from the Universidad Tecnológica del Perú, who evaluated the clarity, presentation, suitability, appropriateness, and purpose of the items. To guarantee the anonymity of the participants, codes were used, and the participants were allowed to review and verify their responses.

The study followed the ethical guidelines established by MDPI for research involving human subjects and adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. The researchers explained that the study was for academic purposes, that participation was voluntary, and that participants could withdraw at any time. In addition, the confidentiality of the responses was assured and they were only accessible to the researchers.

2.3. Data Analysis

In this research, the inductive method was applied based on the survey and the observation sheet, which is appropriate in quantitative research with an inductive beginning or with vaguely defined topics, following a closed data collection method. Inductive survey and observation sheet analysis is a quantitative method. The advantages of this method include sensitivity to content, applicability to highly flexible research designs, and flexibility to analyze various types of quantitative data (

Hernández et al. 2014).

Compared to other analyses in quantitative research, the survey allows the researchers to describe and evaluate in detail the entrepreneurial competencies of the immigrant women of the Children’s Village of the Lambayeque Region. In addition, in this study, the observation sheet was applied to evaluate the products of each workshop, which is very important for its ability to capture the real and practical performance of the women in their enterprises.

The correlation analysis of the entrepreneurial capabilities followed the Preparation phase, which included the identification of the competencies for data collection and sampling. Before starting the analysis, the researchers read the data several times to familiarize themselves with it. Then, they defined the units of analysis, which were each of the competencies in relation to the age, nationality, and educational level of the participants.

The organization phase involved the collection and abstraction of the data and interpretation and verification of the representativeness of the sample data collected. At this stage, codes were identified from the data. The researchers compared the similarities and differences in content between the data in order to proceed to group them by dimension. After grouping, it was identified that the abstraction process should continue by grouping the subconcepts according to the similarities in the data according to the variables analyzed.

All these data were entered into an Excel database grouped by dimension abilities. Then, a matrix was created in SPSS, version 28, where first the arithmetic mean of each variable and dimension was calculated. Subsequently, they were grouped by level of achievement and then correlations of entrepreneurial skills with respect to nationality. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate the differences in entrepreneurial skills (such as opportunity seeking, risk anticipation, persistence, self-demand, etc.) between different groups of women, Logistic Regression Analysis was used to determine the factors influencing the probability of entrepreneurial success among the women studied, and finally, principal component analysis (PCA) was used to determine the factors influencing the probability of entrepreneurial success among the women studied between different groups of women, reduce the dimensionality of the data, and identify the underlying factors explaining entrepreneurial capabilities.

2.4. Entrepreneurial Competencies Model

The model of entrepreneurial competencies for Venezuelan and Peruvian immigrant women is based on the research hypotheses, with the general hypothesis as the central core. Here, entrepreneurial competence acts as the main axis, to which all entrepreneurial capabilities are linked, suggesting that these capabilities are essential components of entrepreneurial competence in these women. (See

Figure 1).

Specifically, hypothesis 1 analyzes, from the perspective of nationality, groups of competencies such as persistence and confidence (PC), risk anticipation (AR), and opportunity seeking and initiative (BOI), suggesting that nationality has a significant influence on these skills. This implies that cultural and contextual differences between nationalities may affect the development and expression of these entrepreneurial competencies.

On the other hand, H2 (Degree of Instruction) is connected with capabilities such as seeking support and information (BAI) and seeking control and excellence (BCE), indicating that the level of formal education influences people’s ability to seek resources and maintain high standards in their ventures.

Finally, age is related to competencies such as self-demand and quality (AC), persistence and confidence (PC), and opportunity seeking and initiative (BOI), suggesting that age, as an indicator of accumulated experience, may influence the strength of these specific competencies.

This model demonstrates that entrepreneurial competencies are interconnected and influenced by demographic factors such as nationality, educational attainment, and age. The general hypothesis covers all entrepreneurial competencies, while H1, H2, and H3 provide a more detailed view, exploring how these competencies may vary as a function of personal and contextual characteristics.

Overall, the model provides a comprehensive understanding of how various factors impact the development and manifestation of entrepreneurial competencies in Venezuelan and Peruvian immigrant women.

3. Results

In the correlation matrix,

Table 1 reveals that Venezuelan immigrant women have a significantly higher representation in the advanced and intermediate levels of competence compared to Peruvian women.

With respect to the level of education, there is a clear influence on the entrepreneurial competencies of immigrant women. Women with secondary education represent the largest group at all levels of competence, especially at the basic level with 66.7%. This suggests that secondary education provides a solid foundation for the development of entrepreneurial skills, although many of these women still need to advance to higher levels of proficiency. Women with completed higher and technical education also show good representation at the advanced and intermediate levels, highlighting the importance of postsecondary education in promoting entrepreneurial skills. However, women with incomplete primary or incomplete university education have a lower representation at the higher levels of proficiency, indicating that these women may face additional challenges in developing their entrepreneurial skills.

Age also plays a crucial role in entrepreneurial skills. Women aged 40 years and older and women aged 35–39 years have a significant representation at the advanced and intermediate levels. In particular, 37.1% of women aged 40 and older are at the advanced level and 45.5% are at the intermediate level, suggesting that experience and maturity can contribute positively to the development of entrepreneurial competencies. In contrast, younger women (20–24 years old) have a lower representation at all competency levels, with only 14.3% at the expert level and 4.5% at the advanced and intermediate levels. This could indicate a lack of experience or training opportunities for younger women compared to their older counterparts.

In summary, the results indicate that Venezuelan women in the Children’s Village in the Lambayeque region tend to have higher entrepreneurial competencies compared to Peruvian women. This is evident in multiple dimensions, such as opportunity seeking, risk anticipation, persistence, self-demand, and seeking external support and information. Differences in entrepreneurial skills can be attributed to cultural factors, previous training, and migratory experiences. These findings highlight the need to design specific support programs that strengthen the entrepreneurial competencies of Peruvian women and take advantage of the strengths of Venezuelan women to foster a more inclusive and equitable entrepreneurial environment.

Hypothesis test

H1. Entrepreneurial skills are significant with respect to the nationality of the immigrant women of the Children’s Village of the Lambayeque Region.

The analysis of

Table 2, regarding entrepreneurial skills according to nationality, reveals notable differences between Peruvian and Venezuelan women in several aspects. Regarding the search for opportunities and initiative, 41% of Peruvian women are at the advanced level, while 20.5% reach the expert level. On the other hand, 57.5% of Venezuelan women are at the advanced level, but only 10% are at the expert level. This indicates that Venezuelan women have a greater tendency to be at the advanced level compared to Peruvian women. Likewise, 23.1% of Peruvian women and 25% of Venezuelan women remain at the intermediate level, while 15.4% of Peruvian women and 7.5% of Venezuelan women remain at the basic level. This indicates that, although a significant proportion of both nationalities made progress, there is still a percentage that remains at the less advanced levels, especially among Peruvian women at the basic level.

In terms of risk anticipation, 35.9% of Peruvian women are at the intermediate level, with only 7.7% reaching the expert level. For Venezuelan women, on the other hand, 47.5% are at the intermediate level and 7.5% are at the expert level. Although both nationalities show a strong presence at the intermediate level, Venezuelans stand out slightly in this category. In addition, 28.2% of Peruvians and 22.5% of Venezuelans remain at the advanced and basic levels. This distribution suggests that although most of the participants advanced to higher levels, a considerable number are still at levels that indicate moderate or initial development in the ability to anticipate risks, with a relatively high proportion of Peruvians at the basic level.

In terms of persistence and confidence, 41% of Peruvian women are at the basic level and 25.6% are at the advanced level, while 20.5% reached the expert level. In contrast, 35% of Venezuelan women are at the advanced level and only 15% are at the expert level. This suggests that Venezuelan women have greater persistence and confidence at the advanced level, while Peruvian women stand out at the extremes, both at the basic and expert levels. It is observed that 12.8% of Peruvian women and 22.5% of Venezuelan women remain at the intermediate level, while 41% of Peruvian women and 27.5% of Venezuelan women remain at the basic level. This result suggests that, after the workshops, a significant portion of the women, especially Peruvian women, continue to show a low level of persistence and confidence, which may require additional interventions to strengthen these capacities.

Self-demand and quality reflect that 28.2% of Peruvian women are experts, but 33.3% are at the basic level, 20.5% are at the advanced level, and only 17.9% are at the basic level. For Venezuelan women, on the other hand, 37.5% are at the intermediate level and 17.5% are at the expert level, similar to the intermediate and basic levels. Peruvian women, therefore, show higher self-demand at the expert level, while Venezuelan women predominate at the intermediate level. This pattern indicates that although the workshops have had a positive impact, there is still a significant portion remaining that require further development to reach higher levels of self-demand and quality.

In terms of seeking support and information, 46.2% of Peruvian women are at the intermediate level, with only 5.1% reaching the expert level. Venezuelan women, however, have 35% at the intermediate level and 10% at the expert level. Although both nationalities excel at the intermediate level, Venezuelan women show a greater inclination towards the expert level. While 28.5% of Peruvians and 25.0% of Venezuelans are at the advanced level, 20.5% of Peruvians and 30% of Venezuelans are at the basic level. This result suggests that although a good part of the participants have made progress, there is a persistent need to improve these skills, especially among Venezuelan women at the basic level.

The search for control and excellence reveals that 28.2% of Peruvian women are experts, 25.6% are at the intermediate level, and 23.1% are at the advanced and basic level. On the other hand, 45% of Venezuelan women are at the advanced level, 22.5% are at the expert and intermediate level, and 10.0% persist at the basic level. These results indicate that although Venezuelan women have made more progress compared to Peruvian women, a significant proportion of both nationalities still needs additional support to achieve greater control and excellence in their enterprises.

In terms of propositionality, 30.8% of Peruvian women are at the expert level, while 28.2% are at the advanced level. In contrast, 47.5% of the Venezuelan women are at the advanced level, with 25% at the expert level. Some 25.6% of Peruvian women and 22.5% of Venezuelan women remain at the intermediate level, while 15.4% of Peruvian women and 5% of Venezuelan women remain at the basic level. Although Venezuelan women tend to predominate at the advanced level, while Peruvian women are more represented at the expert level, there is still a minority that remains at the basic and intermediate levels, suggesting the need to continue strengthening these capabilities.

The capacity for compliance and responsibility shows that 35.9% of Peruvian women are at the intermediate level, with 28.2% at the expert level, 20.5% at the advanced level, and 15.4% at the basic level. Venezuelan women, on the other hand, have 42.5% at the intermediate level and 27.5% at the expert level, while 25.0% are at the advanced level and only 5.0% remain at the basic level. Both nationalities are strongly represented at the advanced level, although Venezuelan women have a slight advantage in this regard. This reflects that although the majority have achieved significant development in these areas, there is still a percentage of women, mostly Peruvian, who need further support to improve their capacity for compliance and accountability.

Finally, the future forecast reveals that 51.3% of Peruvian women are at the intermediate level, 25.6% are at the advanced level, with only 12.8% reaching the expert level, and 10.3% are at the basic level. Venezuelan women, on the other hand, have 40% at the intermediate level and 20% at the expert level, while 25% are at the advanced level and 15% are at the basic level. These results suggest that although Peruvian women have mostly progressed to the intermediate level, there is still a portion that require greater focus on developing their ability to foresee the future. Although Peruvian women predominate at the intermediate level, Venezuelan women show greater representation at the expert level.

In summary, although the workshops have been effective in improving the entrepreneurial skills of the participants, there is still a considerable percentage of women who remain at the basic and intermediate levels. This analysis highlights the need to continue to provide additional support and resources to help these women advance to higher levels of entrepreneurial performance, especially in the skills of persistence, self-demand, and foresight.

He1. There are significant differences in the following abilities: search for opportunities and initiative, anticipation of risk, persistence and confidence, self-demand and quality with respect to the nationality of the immigrant women of the Children’s Villages of the Lambayeque Region.

The ANOVA analysis presented in

Table 3, which evaluates the entrepreneurial skills of the immigrant women of the Children’s Village of the Lambayeque Region, shows that there are no statistically significant differences between the groups evaluated in any of the skills analyzed.

These results as a whole indicate that, for all skills analyzed, the differences between groups of women are not strong enough to be considered statistically significant, suggesting that the observed variation in entrepreneurial skills is more attributable to within-group factors than to differences between the groups themselves.

He2. The success of self-management and quality, information seeking, and excellence in the Venezuelan immigrant women of the Children’s Village of the Lambayeque Region.

Table 4 shows the fit information of the models by various metrics, such as the AIC (Akaike’s Information Criterion), the log likelihood, and the chi-square. The AIC, which is a criterion for model selection, indicates that the final model has a value of 98.213, significantly lower than the model with the intersection alone (186.713). This suggests that the final model is a better fit to the data. Also, the chi-square associated with the final model is significant (

p < 0.05), which reinforces the suitability of the final model for predicting the success of the dependent variable.

Table 5 presents the pseudo R-squared values (Cox and Snell, Nagelkerke, and McFadden) that indicate the percentage of variance explained by the model. The Nagelkerke (R2 = 0.881R^2 = 0.881R2 = 0.881) and Cox and Snell (R2 = 0.808R^2 = 0.808R2 = 0.808) values suggest a model that explains a considerable percentage of the variance of the dependent variable. The McFadden value (R2 = 0.662R^2 = 0.662R2 = 0.662) also supports the robustness of the model, although generally is lower than the other two, which is typical in pseudo R-squares.

Table 6 presents the estimates of the logistic regression parameters that analyze the capabilities related to the entrepreneurship of Peruvian and Venezuelan migrant women. The coefficient of −72.832 with a significance of 0.979 is not statistically significant (sig. > 0.05), which implies that the intercept is not statistically significant to the model.

Regarding nationality 1 (Peruvian), the coefficient is −56.495, suggesting that there is no significant effect of this variable in the model. However, the Exp(B) value and the confidence interval is extremely high, suggesting numerical overflow. As for nationality 2 (Venezuelan), the coefficient is −67.403. However, the Exp(B) value and the confidence interval is extremely high, suggesting a numerical overflow.

As for the self-management and quality capability, the coefficient of 28.601 is extremely high, suggesting an extremely strong positive impact on the likelihood of entrepreneurial success. However, the value of Exp(B) and the ppp-value suggests that, despite the high coefficient, this factor is not statistically significant in this particular context.

In reference to the information search ability, the coefficient of 15.302 indicates a strong positive effect on the probability of success. However, the Exp(B) value and the confidence interval show a numerical overflow. This implies that those entrepreneurs who focus on information seeking are more likely to succeed, underscoring the importance of being well-informed in entrepreneurship. Likewise, in the capacity of search for control and excellence and search for opportunities and initiative, these show coefficients of 14.349 and 13.584, which are positive and high, which imply a positive association with entrepreneurial success. However, the Exp(B) value and the confidence interval show numerical overflow. This ability indicates that entrepreneurs who pursue excellence have a considerable advantage in achieving their entrepreneurial goals.

Finally, the self-management and quality capacity has a negative coefficient (−0.108), which is negative and high, which implies a positive association with entrepreneurial success. However, the Exp(B) value and the confidence interval present numerical overflow, suggesting an inverse relationship, although this is not significant.

In conclusion, the variables related to self-demand and quality, the search for opportunities, and control and excellence show high coefficients, suggesting that these factors play an important role in the ability of migrant women to prosper in their ventures. Despite data overflow problems, it can be inferred that these skills are essential for entrepreneurial success in both Peruvian and Venezuelan women. The analysis shows the resilience and determination of these women in contexts of adversity, characteristics that are reflected in their constant search for opportunities and their self-demand to achieve high standards. This is particularly relevant for migrant women, who face additional social and economic challenges in their entrepreneurial trajectories.

He3. There are underlying patterns and structures in the entrepreneurial capacities of immigrant women in the Children’s Villages of the Lambayeque Region.

Table 7 indicates the communalities, which indicate the proportion of each variable that is explained by the extracted components. The communalities for the entrepreneurial capabilities range from 0.517 to 0.758, suggesting that the identified components explain a considerable part of the variability of each capability. Specifically, self-demand and quality (0.758), risk anticipation (0.673) and persistence and confidence (0.658) are the capabilities with the highest communality, indicating that they are well represented by the extracted components.

Table 8 shows the total variance explained by the two principal components extracted. The first component explains 45.777% of the total variance, while the second component explains an additional 11.886%, thus accumulating 57.663% of the total variance.

Table 9 presents two underlying components that summarize the most relevant factors of entrepreneurship skills among migrant women from SOS Children’s Villages in the Lambayeque Region.

Component 1: Self-management, confidence, and perseverance, with high loadings in variables such as persistence and confidence (0.184), self-demand and quality (0.184), and risk anticipation (0.175), seems to group factors related to the ability of these women to face challenges with determination, maintaining a proactive attitude in the face of uncertainty. These qualities are key to entrepreneurial success, especially in adverse contexts, such as that of migrant women, who frequently have to face situations of economic, social and personal instability. Perseverance and confidence in their abilities stand out as essential competencies for the creation and sustainability of their businesses, reflecting the ability to adapt to and overcome barriers.

Component 2: Compliance, responsibility, and excellence, with variables such as compliance and responsibility (0.483) and pursuit of control and excellence (0.362), is associated with a focus on order and discipline and the desire to achieve high-quality standards in their undertakings. Venezuelan and Peruvian migrant women who manage to develop these skills show a more structured entrepreneurial profile, oriented towards meeting goals and standards. This component could be linked to the formalization and professionalization of their activities, an important aspect for consolidating their enterprises in competitive and normatively demanding markets.

The combination of these two components suggests a balanced entrepreneurial profile, in which migrant women not only rely on their ability to overcome adversity with confidence and perseverance (Component 1) but also adopt a responsible and excellence-oriented attitude in the management of their projects (Component 2). This balance is essential to navigate the difficulties inherent to entrepreneurship in a migratory context, which requires both emotional resilience and planning and management skills.

In conclusion, Venezuelan and Peruvian migrant women have entrepreneurial skills that integrate both self-management and confidence in their own resources, as well as responsibility and a focus on excellence. This dual profile is crucial in migration contexts, where entrepreneurship can not only be a source of income but also a mechanism to rebuild their professional and personal identity. These capabilities allow them to face vulnerability and take advantage of opportunities in a hostile environment, which reinforces the importance of policies and support programs that enhance these skills in the entrepreneurial field.

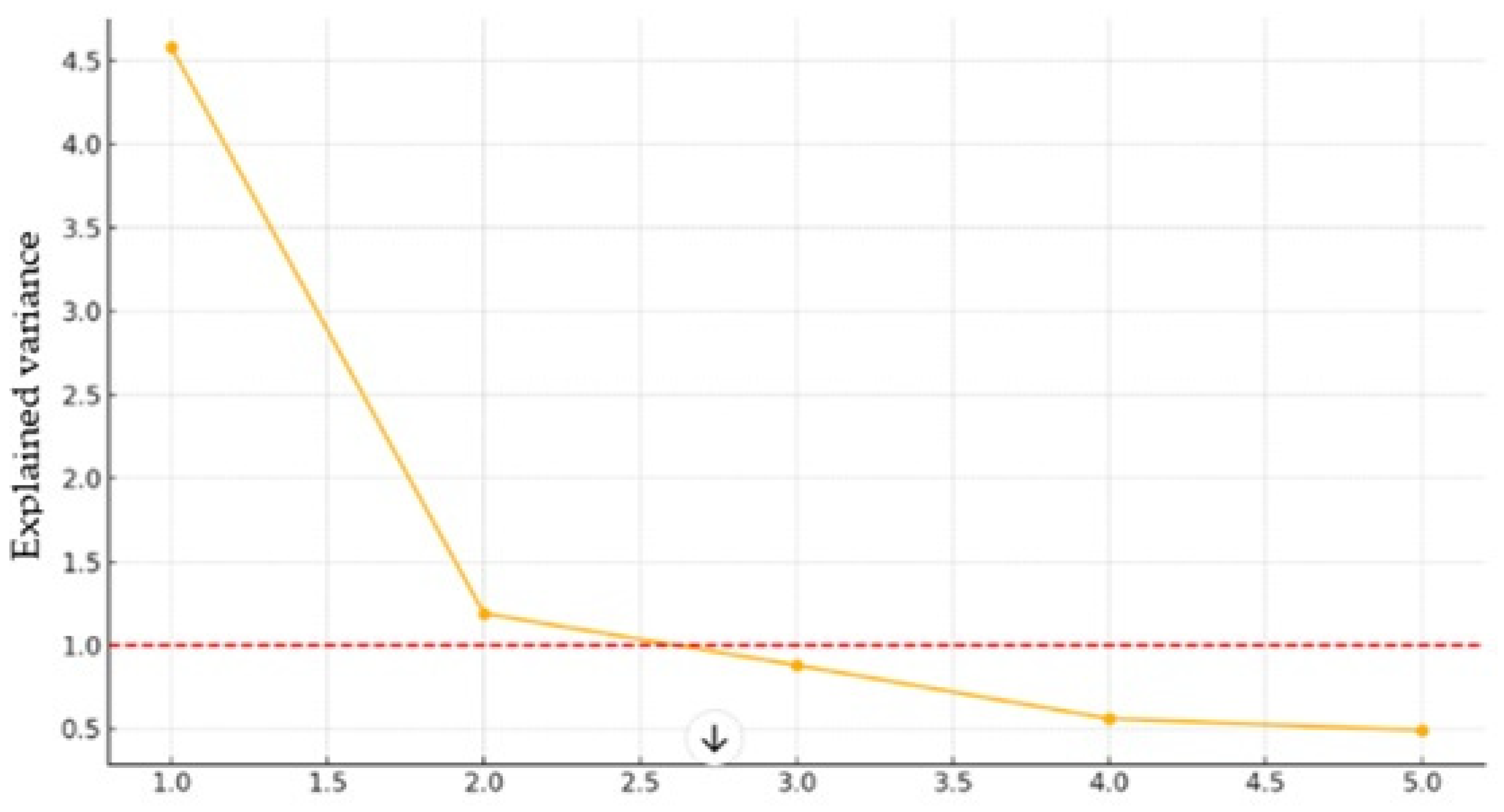

The

Figure 2 suggests that the first two dimensions capture most of the relevant information on entrepreneurial capabilities, while the other components add very little additional information. The sedimentation figure justifies the retention of these two principal components, which explain approximately 57.663% of the total variance, simplifying the analysis and facilitating the interpretation of the data without losing critical information. This provides a clear picture of how the entrepreneurial competencies cluster and underscores the importance of the principal components, offering valuable guidance for the development of training programs targeting immigrant women.

A scatter plot, in the context of PCA, typically shows the projection of the data in the space defined by the first two principal components. This helps to visualize how immigrant women are grouped according to their entrepreneurial competencies. Patterns can be observed here, such as the formation of two clusters, indicating similarities and differences in the assessed competencies of immigrant women: For Component 1, women have high scores in competencies related to initiative and quality. For Component 2, women have moderate scores in competencies related to control and responsibility. This suggests that there are two dominant profiles in terms of entrepreneurial competencies. Training and support strategy initiatives can be tailored to address the specific needs of immigrant women.

The

Figure 3 suggests a clear differentiation between immigrant women who have high levels of entrepreneurial skills (expert and advanced) and those with more basic skills (intermediate and basic). The former seem to be better represented by components that capture more advanced and specific skills, while the latter are associated with a more general or incipient skill profile. This distribution can provide a guide for targeted training programs, depending on the level of capacity of immigrant women, and underscores the need for differentiated strategies that address the specific needs of each group.