The Dimensions of Entrepreneurial Orientation in Franchise Networks: Exploring the Role of Franchisee Associations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Franchise Networks

2.2. Franchisee Provenance—The Business Diversity Provided by Franchisees’ Varied Backgrounds

2.3. Franchising and Entrepreneurship

2.4. Franchisee Associations

3. Conceptual Framework

Entrepreneurial Orientation

4. Methods

4.1. Methodology

4.2. Case Description

4.3. Data Collection and Analysis

5. Findings

5.1. The Apparent Activation of the Dimensions of EO by MWAFMCA

5.1.1. The Big One Burger (1991–1997)

5.1.2. The Big One Burger and the Activation of the Dimensions of EO by MWAFMCA

5.1.3. Tender Roast-Chicken (2001–2004)

5.1.4. Tender Roast-Chicken and the Activation of the Dimensions of EO by MWAFMCA

5.1.5. Frozen Carbonated Beverages (2006–2022 and Beyond)

5.1.6. Frozen Carbonated Beverages Activation of the Dimensions of EO by MWAFMCA

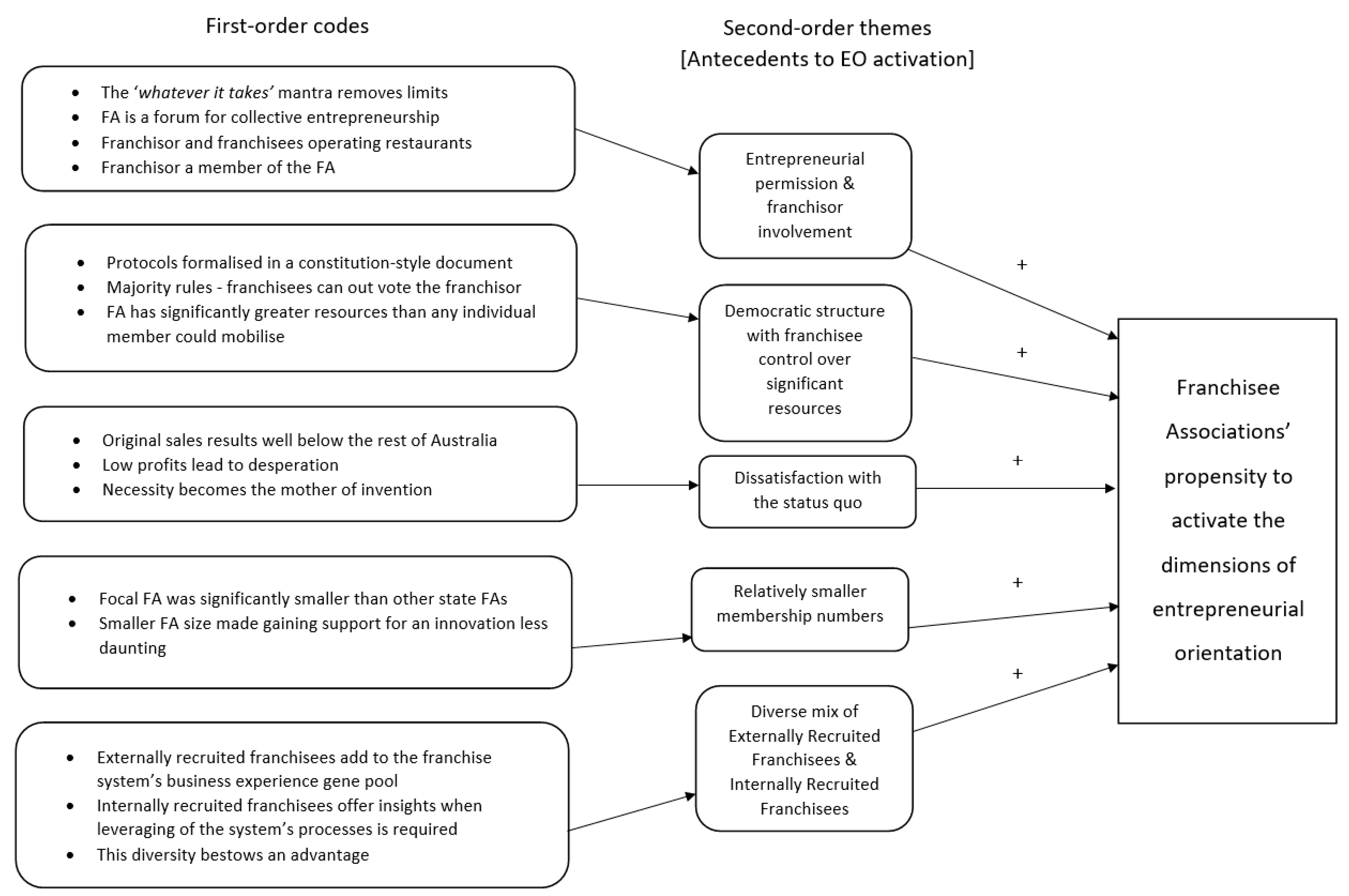

5.2. Antecedents of Franchisee Associations’ Propensity to Activate the Dimensions of EO

5.2.1. Entrepreneurial Permission and Franchisor Involvement

5.2.2. Democratic Structure with Franchisee Control over Significant Resources

5.2.3. Dissatisfaction with the Status Quo

5.2.4. Relatively Smaller Membership Numbers

5.2.5. Diverse mix of Externally Recruited Franchisees and Internally Recruited Franchisees

6. Discussion

6.1. Practical Implications

6.2. Research Contributions, Implications and Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alaydi, Sharif, Trevor Buck, and Yee Kwan Tang. 2021. Strategic responses to extreme institutional challenges: An MNE case study in the Palestinian mobile phone sector. International Business Review 30: 101806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsarini, Peter, Claire Lambert, and Marie Ryan. 2022. Why franchisors recruit franchisees from the ranks of their employees. Journal of Strategic Marketing 30: 180–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsarini, Peter, Claire Lambert, Maria Ryan, and Martin MacCarthy. 2021. Subjective knowledge, perceived risk, and information search when purchasing a franchise: A comparative exploration from Australia. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 14: 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, Jay. 1991. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management 17: 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baucus, David A., Melissa S. Baucus, and Sherrie E. Human. 1996. Consensus in franchise organizations: A cooperative arrangement among entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing 11: 359–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burawoy, Michael. 1998. The extended case method. Sociological Theory 16: 4–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, Shih-Yi. 2014. Franchisor resources, spousal resources, entrepreneurial orientation, and performance in a couple-owned franchise outlet. Management Decision 52: 916–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciambotti, Giacomo, Matteo Pedrini, Bob Doherty, and Mario Molteni. 2023. Unpacking social impact scaling strategies: Challenges and responses in African social enterprises as differentiated hybrid organizations. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research 29: 25–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Classic Clips 1990–2000. 2013. McDonald’s Commercial 1991 The Big One [Video]. YouTube. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UnIT71h3MM0 (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Covin, Jeffrey G., and Danny Miller. 2014. International entrepreneurial orientation: Conceptual considerations, research themes, measurement issues, and future research directions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 38: 11–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, Jeffrey G., and G. T. Lumpkin. 2011. Entrepreneurial orientation theory and research: Reflections on a needed construct. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 35: 855–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, Jeffrey G., and William J. Wales. 2018. Crafting high-impact entrepreneurial orientation research: Some suggested guidelines. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 43: 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumberland, Denise M. 2015. Advisory councils in franchising: Advancing a theory-based typology. Journal of Marketing Channels 22: 175–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dada, Olufunmilola, and Anna Watson. 2013. Entrepreneurial orientation and the franchise system. European Journal of Marketing 47: 790–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dada, Olufunmilola (Lola), Anna Watson, and David A. Kirby. 2012. Toward a model of franchisee entrepreneurship. International Small Business Journal 30: 559–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dada, Olufunmilola (Lola), Anna Watson, and David Kirby. 2015. Entrepreneurial tendencies in franchising: Evidence from the UK. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 22: 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandridge, Thomas C., and Cecilia M. Falbe. 1994. The influence of franchisees beyond their local domain. International Small Business Journal 12: 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, W. Gibb, and Alan L. Wilkins. 1991. Better stories, not better constructs, to generate better theory: A rejoinder to Eisenhardt. The Academy of Management Review 16: 613–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen M., and Melissa E. Graebner. 2007. Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal 50: 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geary, John, and Roberta Aguzzoli. 2016. Miners, politics and institutional caryatids: Accounting for the transfer of HRM practices in the Brazilian multinational enterprise. Journal of International Business Studies 47: 968–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillis, William, and Gary J. Castrogiovanni. 2012. The franchising business model: An entrepreneurial growth alternative. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 8: 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, Dennis A., Kevin G. Corley, and Aimee L. Hamilton. 2013. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research. Organizational Research Methods 16: 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunhagen, Marko, Robin B. Dipietro, Robert E. Stassen, and Lorelle Frazer. 2008. The effective delivery of franchisor services: A comparison of U.S. and German support practices for franchisees. Journal of Marketing Channels 15: 315–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, Greg, Arwen Bunce, and Laura Johnson. 2006. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 18: 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, Mathew, and Robert E. Morgan. 2007. Deconstructing the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and business performance at the embryonic stage of firm growth. Industrial Marketing Management 36: 651–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, Patrick J., and Sevgin Eroglu. 1999. Standardization and adaptation in business format franchising. Journal of Business Venturing 14: 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketchen, David J., R. Duane Ireland, and Charles C. Snow. 2007. Strategic entrepreneurship, collaborative innovation, and wealth creation. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 1: 371–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keynes, John Maynard. 1936. The General Theory of Employment Interest and Money. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Labuschagne, Adri. 2003. Qualitative research—Airy fairy or fundamental? The Qualitative Report 8: 100–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashley, Conrad, and Alison J. Morrison. 2000. Franchising Hospitality Services. Oxford: Butterworth/Heinmann. [Google Scholar]

- Law Insider. 2023. Quick-Service Restaurants Definition. Available online: https://www.lawinsider.com/dictionary/quick-service-restaurants (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Lawrence, Benjamin, and Patrick J. Kaufmann. 2010. Franchisee associations: Strategic focus or response to franchisor opportunism. Journal of Marketing Channels 17: 137–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, Benjamin, and Patrick J. Kaufmann. 2011. Identity in franchise systems: The role of franchisee associations. Journal of Retailing 87: 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Yuan, Yongbin Zhao, Justin Tan, and Yi Liu. 2008. Moderating effects of entrepreneurial orientation on market orientation-performance linkage: Evidence from Chinese small firms. Journal of Small Business Management 46: 113–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G. T., and Gregory Dess. 1996. Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. The Academy of Management Review 21: 135–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G. T., and Gregory Dess. 2001. Linking two dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation to firm performance: The moderating role of environment and industry life cycle. Journal of Business Venturing 16: 429–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madanoglu, Melih, Gary J. Castrogiovanni, and Murat Kizildag. 2019. Franchising and firm risk among restaurants. International Journal of Hospitality Management 83: 236–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahasuar, Kiran. 2023. Strategic choices of an MNE in an emerging market: The case of Perfetti Van Melle. Journal of Strategic Marketing 31: 1012–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maze, Jonathan. 2021. Franchisees Are behind Some Iconic Menu Items. Available online: https://www.restaurantbusinessonline.com/financing/franchisees-are-behind-some-iconic-menu-items (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- McDonald’s Corporation. 2022. McDonald’s Reports Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2021 Results. January 27. Available online: https://corporate.mcdonalds.com/corpmcd/our-stories/article/Q4-2021-results.html (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Michael, Steven C. 2003. First mover advantage through franchising. Journal of Business Venturing 18: 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Chet C., Laura B. Cardinal, and William H. Glick. 1997. Retrospective reports in organizational research: A reexamination of recent evidence. Academy of Management Journal 40: 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Danny, and Isabelle Le Breton-Miller. 2017. Underdog entrepreneurs: A model of challenge-based entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 41: 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovanović, Bojan Morić, Mirjana Grčić Fabić, and Vjekoslav Bratić. 2023. Strategic Approach to Configurational Analysis of Entrepreneurial Orientation, Strategic Networking, and Sme Performance Within Emerging Markets of Selected Southeast European Countries. Administrative Sciences 13: 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumdžiev, Nada, and Josef Windsperger. 2011. The Structure of Decision Rights in Franchising Networks: A Property Rights Perspective. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 35: 449–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, Seth W. 1988a. An empirical look at franchising as an organizational form. The Journal of Business 61: 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, Seth W. 1988b. Franchising, brand name capital, and the entrepreneurial capacity problem. Strategic Management Journal 9: 105–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perryman, Alexa A., and James G. Combs. 2012. Who should own it? An agency-based explanation for multi-outlet ownership and co-location in plural form franchising. Strategic Management Journal 33: 368–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QSR Magazine. 2023. Ranked the Top 50 Fast-Food Chains in America. Available online: https://www.qsrmagazine.com/fast-food/ranked-top-50-fast-food-chains-america (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Quintal, Vanessa, and Ian Phau. 2014. Examining consumer risk perceptions of prototypical brands versus me-too brands. Journal of Promotion Management 20: 115–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, Hannah, and Max Roser. 2019. Meat and Dairy Production Our World in Data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/meat-production (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Sen, Sandipan, Katrina Savitskie, Raj V. Mahto, Sampath Kumar, and Dmitry Khanin. 2023. Strategic flexibility in small firms. Journal of Strategic Marketing 31: 1053–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergeeva, Natalya. 2016. What makes an “innovation champion”? European Journal of Innovation Management 19: 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, Scott A., and Frank Hoy. 1996. Franchising: A gateway to cooperative entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing 11: 325–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoebridge, Neil. 2008. McDonald’s Chooks Everything into Mix. Australian Financial Review. Available online: https://www.afr.com/companies/media-and-marketing/mcdonalds-chooks-everything-into-mix-20081020-j8ftb (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Shriber, Sara. 2023. Fast-Food Chains That Rank Among Gen Z–Chick-Fil-A Is No.1. Available online: https://civicscience.com/fast-food-chains-that-rank-among-gen-z-chick-fil-a-is-no-1/#:~:text=For%20one%2C%20Gen%20Z%20is,%25%20of%20the%20Gen%20Pop) (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Siggelkow, Nicolaj. 2007. Persuasion with case studies. Academy of Management Journal 50: 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storholm, Gordan, and Eberhard Scheuing. 1994. Ethical implications of business format franchising. Journal of Business Ethics 13: 181–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Kate. 2015. Why the Most American Fast-Food Chain Is Using Australia as Its Testing Ground. Entrepreneur. Available online: https://www.entrepreneur.com/franchises/why-the-most-american-fast-food-chain-is-using-australia-as/251238 (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Teddlie, Charles, and Fen Yu. 2007. Mixed methods sampling: A typology with examples. Journal of Mixed Methods Research 1: 77–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadham, Helen, and Richard C. Warren. 2014. Telling organizational tales: The extended case method in practice. Organizational Research Methods 17: 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wales, William John. 2016. Entrepreneurial orientation: A review and synthesis of promising research directions. International Small Business Journal 34: 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wales, William J., Jeffrey Covin, and Erik Monsen. 2020. Entrepreneurial orientation: The necessity of a multilevel conceptualization. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 14: 639–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, Achim, Michael Auer, and Thomas Ritter. 2006. The impact of network capabilities and entrepreneurial orientation on university spin-off performance. Journal of Business Venturing 21: 541–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, Anna, Olufunmilola (Lola) Dada, Marko Grünhagen, and Melody Wollan. 2016. When do franchisors select entrepreneurial franchisees? an organizational identity perspective. Journal of Business Research 69: 5934–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, Anna, Olufunmilola (Lola) Dada, Owen Wright, and Rozenn Perrigot. 2019. Entrepreneurial orientation rhetoric in franchise organizations: The impact of national culture. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 43: 751–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, Catherine, Eriikka Paavilainen-Mäntymäki, Rebecca Piekkari, and Emmanuella Plakoyiannaki. 2022. Reconciling theory and context: How the case study can set a new agenda for international business research. Journal of International Business Studies 53: 4–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitbourn, Michaela. 2020. McDonald’s Sues Hungry Jack’s over Big Jack Burger. Sydney: The Sydney Morning Herald. Available online: https://www.smh.com.au/national/fast-feud-as-mcdonald-s-sues-hungry-jack-s-over-big-jack-burger-20200903-p55s0q.html (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Wiklund, Johan, and Dean A. Shepherd. 2011. Where to from here? EO-as-experimentation, failure, and distribution of outcomes. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 35: 925–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcik-Karpacz, Anna, Sascha Kraus, and Jaroslaw Karpacz. 2022. Examining the relationship between team-level entrepreneurial orientation and team performance. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research 28: 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Robert K. 2018. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, Woojin, Jaeyun Jeong, and Kyoung Won Park. 2021. Informal Network Structure and Knowledge Sharing in Organizations: An Empirical Study of a Korean Paint Manufacturing Company. Administrative Sciences 11: 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Woojin, Sang Ji Kim, and Jaeyong Song. 2016. Top Management Team Characteristics and Organizational Creativity. Review of Managerial Science 10: 757–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zardini, Alessandro, Lamin B. Ceesay, Cecilia Rossignoli, and Raj Mahto. 2023. Entrepreneurial business network and dynamic relational capabilities: A case study approach. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research 29: 328–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

MWAFMCA Member FAMI Denotes Internally Recruited FAME Denotes Externally Recruited |

Years of Franchisee Association Membership | The Big One Burger (1991–1997) | Tender Roast-Chicken (2001–2003) | Frozen Carbonated Beverages (2006–Onward) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAMI#1 * | 23 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| FAMI#2 * | 19 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| FAMI#3 | 25 |  | ✓ | ✓✓ |

| FAMI#4 | 17 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| FAMI#5 | 9 | ✓ |  |  |

| FAMI#6 | 20 |  |  | ✓ |

| FAME#7 | 32 | ✓✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| FAME#8 * | 37 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| FAME#9 | 9 | ✓ | ✓✓ |  |

| FAME#10 | 4 | ✓ |  |  |

| FAME#11 | 7 | ✓ | ✓✓ |  |

| FAME#12 | 12 |  |  | ✓ |

= Not an MWAFMCA member at the time of this innovation. ✓✓ = MWAFMCA member and a key proponent of this innovation. Total MWAFMCA membership years = 214. Total years as MWAFMCA President = 19. * Denotes served as MWAFMCA President.

= Not an MWAFMCA member at the time of this innovation. ✓✓ = MWAFMCA member and a key proponent of this innovation. Total MWAFMCA membership years = 214. Total years as MWAFMCA President = 19. * Denotes served as MWAFMCA President.| Type of Data | Source | Quantity | Use in the Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary data | Semi-structured interviews | 12 interviews of 12 h 37 min total duration | Primary data source for addressing the two research questions |

| Secondary data | Business case-proposal (Tender Roast-chicken) | 43 pages (.pdf) | Provided support, corroboration, and triangulation of interviews |

| Franchising code of conduct (Marketing funds) | 3 pages (.pdf) | ||

| Letters of appreciation | 2 pages (.pdf) | ||

| Franchising overview booklet | 15 pages (.pdf) | ||

| Media releases | 14 pages (.pdf) | ||

| Media articles | 56 pages (.pdf) | ||

| Relevant location photos | 8 pages (.pdf) | ||

| Television commercials listing | 1 page (.pdf) | ||

| Franchisee training courses | 8 pages (.pdf) | ||

| Franchisee awards and artefacts | 5 pages (.pdf) |

| Dimensions of Entrepreneurial Orientation | The Big One Burger | Tender Roast-Chicken | Frozen Carbonated Beverages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Risk-taking | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Proactiveness | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Competitive aggression | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Autonomy | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Balsarini, P.; Lambert, C. The Dimensions of Entrepreneurial Orientation in Franchise Networks: Exploring the Role of Franchisee Associations. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14010002

Balsarini P, Lambert C. The Dimensions of Entrepreneurial Orientation in Franchise Networks: Exploring the Role of Franchisee Associations. Administrative Sciences. 2024; 14(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleBalsarini, Peter, and Claire Lambert. 2024. "The Dimensions of Entrepreneurial Orientation in Franchise Networks: Exploring the Role of Franchisee Associations" Administrative Sciences 14, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14010002

APA StyleBalsarini, P., & Lambert, C. (2024). The Dimensions of Entrepreneurial Orientation in Franchise Networks: Exploring the Role of Franchisee Associations. Administrative Sciences, 14(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14010002