1. Introduction

In coherence with this great practical relevance, research on entrepreneurship education also has grown rapidly (

Fellnhofer 2019). The majority of research focuses on the effects or impacts entrepreneurship education has (

Tiberius and Weyland 2023), such as establishing or increasing entrepreneurial attitudes (

Iyortsuun et al. 2021;

Fayolle and Gailly 2015), entrepreneurial motivation (

Oosterbeek et al. 2010), entrepreneurial intention or volition (

Bae et al. 2014;

Fayolle and Gailly 2015;

Maresch et al. 2016;

Piperopoulos and Dimov 2015;

Rauch and Hulsink 2015;

Zhang et al. 1987), and entrepreneurial competences or skills (

Aly et al. 2021;

Hahn et al. 2020;

Jardim 2021;

Oosterbeek et al. 2010). Among these, the literature has a strong focus on students’ entrepreneurial intention (

Tiberius and Weyland 2023). In other words: Does entrepreneurship education really foster entrepreneurship? As mentioned above, this is seen as its purpose or even raison d’être (

O’Connor 2013). Interestingly,

Bae et al. (

2014) found in their large-scale meta-analysis that there is a significant but only small positive correlation between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intention. This could mean different things: (a) entrepreneurship education is not very effective, (b) entrepreneurial intention is not the most appropriate variable to measure the success of entrepreneurship education, (c) entrepreneurship is not attractive enough for students compared to permanent employment, or (d) the way entrepreneurship education occurs can be improved.

While all these conclusions are feasible, we want to take the last possible notion as a starting point. This thought is in line with the fact that, opposing the strong “output” perspective of EE research mentioned above, the “inside” or process perspective of the way entrepreneurship education occurs receives comparably little attention (

Tiberius and Weyland 2023). In other words: the majority of research that focuses on EE’s impacts more or less treats EE as a homogenous good. However, it is obvious that any subject, such as languages, math, psychology, sciences, etc., can be taught in various ways. The same applies to entrepreneurship. This also addresses the practical relevance of our review: for schools and universities, it is not only relevant to provide any kind of EE but a high quality EE. To be able to evaluate the quality of entrepreneurship programs, it is necessary to take the specific pedagogy of EE into account. This requires knowledge about the curricular items that exist in EE.

To put the way entrepreneurship, as recognizing and acting upon business opportunities (

Filser et al. 2020;

Shane and Venkataraman 2000), is taught and learned in more concrete terms, we want to refer to the concept of the curriculum. While there is a lack of a commonly accepted definition of a curriculum (

Fraser and Bosanquet 2006), there is some consensus on its main dimensions: (0) audiences or target groups, (1) teaching objectives, (2) teaching contents, (3) teaching methods, and (4) assessment methods (

Alberti et al. 2004;

Fayolle and Gailly 2008;

Mwasalwiba 2010;

Tiberius et al. 2023). EE can have various audiences, from primary school (or even kindergarten) to university and even at graduate level, with different previous educational backgrounds. After determining the audience, the actual curricular development begins. Against this background, our research question is as follows: according to the EE literature, what are the (1) teaching objectives, (2) teaching contents, (3) teaching methods, and (4) assessment methods specifically used in entrepreneurship education? In particular, we wanted to collect specific items in these four curriculum dimensions, based on a systematic literature review.

Our literature review contributes to the literature by providing a comprehensive overview of all items in the four curriculum dimensions that have been discussed in entrepreneurship curriculum research so far, by distinguishing between items that directly refer to entrepreneurship and those that refer to business management or other subjects, and by giving an impression on the research intensities of these items. Our review complements previous but outdated reviews with slightly differing methodologies, such as the ones by

Maritz (

2017),

Maritz and Brown (

2013), and

Mwasalwiba (

2010). However, we include their findings in our analysis. This literature review also has practical implications.

2. Methodology

To answer our research question, we conducted a systematic literature review (

Kraus et al. 2020,

2022;

Tranfield et al. 2003). To search for relevant papers, we used the Web of Science (WoS) on 20th August 2023 and repeated the search on the 26th November 2023. The WoS is regarded as a leading database for scholarly literature (

Zhu and Liu 2020), with an especially high coverage of publications in the social sciences (

Norris and Oppenheim 2007;

Singh et al. 2021), which allows diverse filtering functions (

Martín-Martín et al. 2021). To find as many relevant articles as possible, our first attempt was to use the topic search. However, this led to too many results, of which the vast majority were not relevant. For example, the search for “objective*” AND “entrepreneurship education” led to 175 results. After screening the first 50 results without finding a single relevant publication, we decided to use a combined search of specific title terms and the topic term “entrepreneurship education”, as shown in

Table 1. The asterisk (*) was used to also include terms with a different ending (

Granados et al. 2011). Several of the papers appeared in more than one of the searches.

Due to the manageable sample size, we did not narrow down the search by applying further formal inclusion or exclusion criteria, such as document types, categories (scholarly disciplines), or languages. Rather, we screened all the papers’ titles and abstracts to check for their relevance to our research goal. In this process, papers were excluded when their content did not relate to our research question. In particular, a publication was excluded for one of the following reasons: (1) The publication did not address at least one specific item of the four curriculum dimensions. (2) The paper did not deal with entrepreneurship education in general but with specific sub-types, such as social entrepreneurship education (

McNally et al. 2020) or sustainable entrepreneurship education (

Hermann and Bossle 2020). (3) The search term had a different meaning in the article. For example, the outcome of EE can be either a formerly set teaching or learning objective or the (un)intended consequence, effect, or impact of EE. A large share of the impact-oriented papers focused on the impacts of EE not on the individual level of students but on the level of the economy or society, which was also not the focus of our review. The same applies to the three other curriculum dimensions. For example, the search term “method*” was mostly used for research methods. The term “assessment” was also used for evaluation of the entrepreneurship program, whereas our focus was on the assessment of the students’ learning performance. Additionally, the term appeared in specific research contexts, such as the “assessment” of textbooks (

Mason and Siqueira 2014). (4) One paper was excluded because it was written in Russian, which the authors do not understand. Subtracting double or multiple appearances and topical irrelevance, the total number of papers was 26 (

Table 2).

For data analysis, we extracted all statements relating to the four curriculum dimensions. Some of the identified codes were too vague to be included in further analysis and were removed accordingly. For example, in the methodology category,

Maritz and Brown (

2013) mentions traditional and non-traditional teaching methods, which are not specific methods but root categories. Using open coding (

Corbin and Strauss 2014;

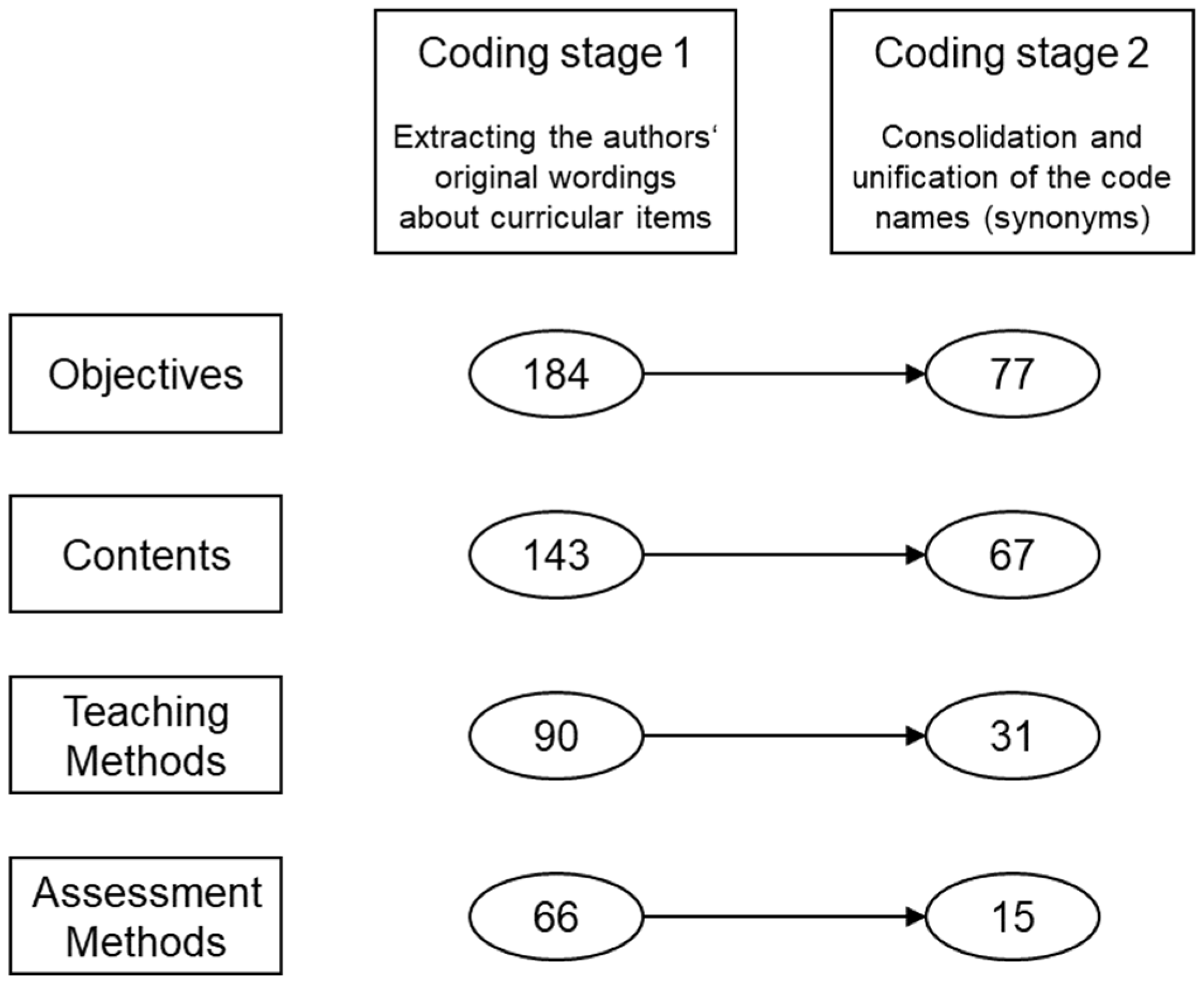

Miles et al. 2014), we collected 184 codes for objectives, 143 codes for contents, 90 codes for teaching methods, and 66 codes for assessments in the first coding stage. In the second stage, we consolidated and unified the code names. As a consequence, the number of codes could be reduced to 77 objectives, 67 contents, 31 teaching methods, and 15 assessment methods (

Figure 1).

When analyzing the data, we did not only count the codes but also how often they were mentioned. However, this is not intended to be interpreted statistically but to provide an impression of how intensely the items are discussed in entrepreneurship curriculum research (

Hannah and Lautsch 2011). A code was counted as one per article, regardless of how often it was mentioned in the article. Some numbers of mentions in the tables exceed the number of articles (26), because the summarized categories contained several codes.

3. Results

In the objective dimension, we found 77 codes, which were mentioned 185 times. The particular objective categories and the numbers of codes and mentions are summarized in

Table 3. The predominant objectives relate to the fields of entrepreneurship and business management, whereas only a few codes relate to other fields.

Following our research goal and in order not to go beyond the scope, we focus on the entrepreneurship-specific objectives, which are provided in greater detail in

Table 4. The conceptualizations of required entrepreneurial knowledge is somewhat weak. At its core, students should know the fundamentals of entrepreneurship, be able to define an entrepreneur, and know the stages of starting a new venture. In contrast, the literature strongly emphasizes entrepreneurial skills, which is in line with an understanding of entrepreneurship as a practice. Accordingly, acting and behaving in an entrepreneurial way requires a variety of entrepreneurial skills. Among them, entrepreneurial alertness, starting a new venture, and entrepreneurial financial skills were addressed most often. The entrepreneurial financial skills have several more sub-codes, such as being able to assess the financial feasibility of the venture, forecast the financial requirements of the new venture, choose the right financing approach, present a business idea to investors and persuade them, acquire the required funding, and plan and control the finances of the venture. Entrepreneurial attitudes are least frequently addressed as teaching and learning objectives. Here, the literature especially stresses that students should develop or increase an entrepreneurial intention and mindset. We did not include the socio-economic outcomes in

Table 3, as they do not relate to the program level directly but address outcomes beyond it, such as creating new jobs (mentioned once), creating an entrepreneurial culture in the university, or creating economic and social value (twice).

In the content dimension, we identified 67 codes mentioned 115 times.

Table 5 showcases the found content categories and the numbers of codes and mentions.

Again, following our research goal, we focus on the contents associated with entrepreneurship, which are listed in greater detail in

Table 6. The literature suggests that entrepreneurship students should become familiar with (unspecified) fundamentals of entrepreneurship. Another strong focus of the literature is on business opportunities and business ideas, where the students should learn how to recognize lucrative business opportunities and how to generate business ideas and assess their feasibility. Further strong foci are on creativity and innovation and the stages of the process of creating a startup.

In the method dimension, we found 31 codes, which were mentioned 76 times. An overview of the different types of learning methods mentioned in the literature (with their numbers of codes and mentions) is given in

Table 7.

Apart from several methods that can be used for many different subjects, we found entrepreneurship- and business-specific methods. The particular entrepreneurship-specific methods and the numbers of mentions are provided in

Table 8. We used the well-established categorization of teaching and learning methods, which distinguishes between teaching “about”, “for”, and “through” entrepreneurship: teaching about entrepreneurship is teacher-centered and, consequently, instruction-based; teaching for entrepreneurship is student-centered and relates to experiential learning, taking place in a risk-free classroom setting; teaching through entrepreneurship is also student-centered and relates to experiential learning, but requires real-life contexts facing real problems and risks (

Chaker and Jarraya 2021;

Jamieson 1984;

Mwasalwiba 2010;

Sirelkhatim and Gangi 2015). The teaching-about-entrepreneurship methods are not indicated separately in the entrepreneurship section, because they are basically methods that are not specific for entrepreneurship but can be used in other fields as well. Project work (either as individual or group work), start-up case studies, and counseling/mentoring are methods addressed most often in the literature. They relate to the teaching-for- or teaching-through-entrepreneurship approach, depending on the method’s application to a fictional or real venture, which was not specified in the papers. In comparison, teaching “through” entrepreneurship is much less discussed.

When coding the assessment methods, it became obvious that the literature deals with two different levels—the assessment of the students’ learning performance and the evaluation of the entrepreneurship programs. The overall results are shown in

Table 9.

Due to our pedagogic perspective on how entrepreneurship is taught and learned, our focus is on the student level. In this student assessment method dimension, we found 15 codes, which were mentioned 27 times. Among them, seven codes, mentioned 11 times, refer to entrepreneurship, with a particular focus on assessment methods that relate to experiential entrepreneurship education, i.e., teaching

for or

through entrepreneurship. For five codes, we were not able to distinguish between teaching

for or

through entrepreneurship, as the methods can be used for both fictional and real start-up projects. We did not sub-classify the general assessment methods that are applicable in other subjects as well because several of the codes found in the literature cannot be attributed to just one but various different assessment classifications. An exemplary classification of (general) assessment methods was provided by

Pittaway and Edwards (

2012), who distinguish between the following characteristics: (1) What is assessed? (2) How is it assessed? (3) When and where is it assessed? (4) Who is doing the assessing? (5) Is the assessment external or internal? (6) Is the assessment objective or subjective? (7) Is the assessment formative or summative? In correspondence with the question “Who is doing the assessing?,” the following can additionally be asked: (8) Who is being assessed—individual students or groups? None of these classifications could cover all the codes found in the literature; hence, using all classifications would have led to double entries; furthermore, the non-entrepreneurship-specific assessment methods do not address our research objective. Therefore, we dispensed with a separate classification.

In the program evaluation dimension, we found much more research, represented by 22 codes, mentioned 32 times, which we attributed to four categories: student, program, start-up, and societal characteristics.

The more detailed entrepreneurship-specific results are provided in

Table 10. On the student level, only seven codes could be found. Among them, business plans are mentioned most often (four times). On the program level, student characteristics show both the highest number of codes and mentions. Among them, four papers have suggested to measure the students’ entrepreneurial intention during or after participating in the program. Three papers wanted to measure entrepreneurial self-efficacy. If these measures are high (possibly in comparison to before participating in the program), the program can be considered as performing well. Entrepreneurial traits as another possible measure was only mentioned once and has to be seen critically, as traits are usually conceptualized as more or less immutable characteristics of an individual. Therefore, measuring traits before and after the program should deliver almost the same values, which makes them unsuitable as performance indicators. Also critical is entrepreneurial orientation, as it usually refers not to individuals but to firms (

Covin and Lumpkin 2011;

Rauch et al. 2009). It also is not very reasonable to assign this code to the start-up characteristics, as entrepreneurial orientation is conceptualized as a strategic orientation usually referring to established firms and not to start-ups, which have a high entrepreneurial orientation by definition. Among the start-up characteristics, the number of new ventures started by students or alumni was mentioned most often (three times).

4. Discussion

This review aimed at identifying items for (1) teaching and learning objectives, (2) teaching and learning contents, (3) teaching methods, and (4) assessment methods specifically used in entrepreneurship education, from a research perspective, i.e., based on a systematic literature review.

The overall results show that, apart from entrepreneurship-specific curriculum items, items relating to business management play a prominent role. This shows that, from the perspective of EE research, both fields are strongly intertwined. When entrepreneurship is seen as new business venturing, it is obvious that, apart from the pre-founding and founding stage, start-ups are firms, and the knowledge and skills relevant for managing firms also applies to new or young firms. The idea that entrepreneurship is a mindset that goes beyond starting new companies and can be applied to non-business areas, such as social ventures (

Gupta et al. 2020;

Hota et al. 2020;

Kirby 2004;

Shahid and Alarifi 2021), is not yet strongly reflected in entrepreneurship curriculum research. Similarly, the potential use of entrepreneurship education for corporate entrepreneurship is still underrepresented (

Glinyanova et al. 2021;

Soares et al. 2021). Apart from business management, other fields that are incorporated to a limited extent include economics, law, and information technology. In line with our research goal, we will focus only on the entrepreneurship-specific items in the following.

In the objective dimension, the findings reveal a focus on entrepreneurial competences or skills, whereas entrepreneurial knowledge and attitudes received less attention. This corresponds to the idea that entrepreneurship is, first and foremost, an activity or behavior (

Gartner 1988;

Mueller et al. 2012) that must be mastered by prospective entrepreneurs. However, the identified competences still lack a systematic, which, for example, is provided by the EntreComp conceptual model, which differentiates three areas with several competences for each: “ideas and opportunities” (spotting opportunities, creativity, vision, valuing ideas, and ethical and sustainable thinking), “resources” (self-awareness and self-efficacy, motivation and perseverance, mobilizing resources, financial and economic literacy, and mobilizing others), and “into action” (taking the initiative, planning and management, coping with ambiguity, uncertainty, and risk, working with others, and learning through experience) (

Bacigalupo et al. 2016). Whereas coping with ambiguity, uncertainty, and risk is considered highly relevant for entrepreneurship, it is underrepresented in the EE curriculum literature. The consequences of external crises has not been addressed yet (

Drăgan et al. 2023). Interestingly, in the entrepreneurial knowledge category, knowing entrepreneurial theories and concepts is not explicitly mentioned. In the entrepreneurial attitude category, developing or increasing an entrepreneurial mindset (or passion or spirit) and intention was only mentioned by some papers. Future research may place more emphasis on these categories, as skilled behavior should be based on solid knowledge and is strongly influenced by attitudes.

In the content dimension, we found a comparably large number of codes, which were addressed by a relatively low number of articles each. The whole catalogue represents a broad and comprehensive entrepreneurship syllabus, in which no substantial contents are missing; its individual items have little support as many of them are only mentioned once or twice. This suggests a lack of a common canon of contents that should be taught. Future research should engage in a more holistic perspective in search for such a canon.

In the method dimension, we found several entrepreneurship-specific methods, which can all be considered as experiential methods. Experiential methods are seen as particularly suitable and effective for entrepreneurship education, as they relate to simulated or actual entrepreneurial activities and behaviors (

Awaysheh and Bonfiglio 2017;

Bell and Bell 2020;

Kirby 2004;

Lackéus 2020;

Morris and König 2020;

Motta and Galina 2023;

Smith et al. 2022). However, the number of codes was quite small, and these were mentioned by only a few articles each. Several further entrepreneurship-specific methods are missing, such as the lean startup approach, which has been mentioned in the content but not the method dimension. Due to its incremental and iterative procedure, the lean start-up approach can be seen as an alternative to writing a business plan, which tries to holistically plan a new venture over several years (

DeNoble and Zoller 2017;

Schultz 2022). Similarly, the iterative process of design thinking is considered useful for EE but is underrepresented in the literature (

Kremel and Wetter Edman 2019;

Rösch et al. 2023). In addition, entrepreneurship projects, regardless of whether they are conducted as individual vs. group work or by referring to a fictional vs. real case, could be further refined. This also applies to business incubators (

Albort-Morant and Oghazi 2016;

Deyanova et al. 2022;

Guerrero et al. 2020;

Grimaldi and Grandi 2005) and accelerators (

Dams et al. 2021;

Seet et al. 2018) as methods for entrepreneurship education. As the entrepreneurship process can be subdivided into numerous partial tasks, these could also be used as entrepreneurial subprojects. For example, students could work on brand name and logo development, business idea development (

Secundo et al. 2023), business model development (

Bolzani and Luppi 2021;

Hasche and Linton 2021;

Snihur et al. 2021), company registration, entrepreneurial marketing (

Amjad et al. 2020;

Thanasi-Boçe 2020), (minimum viable) product/service development (

White and Kennedy 2022;

Wu and Chen 2021), etc. Apart from subdividing the whole entrepreneurship process into partial projects, a more demanding approach, for both students and instructors, is to undergo the whole process from idea to market. For simpler business ideas, such as a t-shirt shop, this could be realized in one semester or a year, whereas more complex ideas may take much longer, especially when they refer to real, rather than fictional, cases (teaching-

through-entrepreneurship). Again, the low numbers suggest a strong potential for enhanced curricular research on teaching methods in entrepreneurship education.

In the assessment dimension, a similar picture can be observed: both the number of assessment methods and the number of times they were addressed by individual papers were low. In principle, the experiential teaching methods can also be used for assessment purposes—either by assessing the students’ performance during the process (formative assessment) or by focusing on the results the students elaborated (summative assessment). As the literature does not seem to have realized this potential sufficiently, future research should examine the validity of experiential teaching arrangements as assessment methods and investigate the advantageousness of formative or summative assessments.

As with all research, our study comes with several limitations. First, the literature review is based on (only) 26 papers, which represents the current stock of research. This relatively low number shows that research in the subfield of entrepreneurship curricula still plays a subordinate role in the otherwise extensive research on entrepreneurship education (

Fellnhofer 2019;

Tiberius and Weyland 2023). While the research interest may rise in the future, the current state of research may be biased simply due to the low sample size and selected priorities of individual authors.

Second, we only used English search terms, because this is the main scholarly language and because of our own language limitations. Therefore, interesting articles in other languages could not be included (e.g.,

Castro 2017). As a consequence, a western bias can occur, which does not take into account EE in developing or emerging countries or the perspective of immigrant entrepreneurs in developed countries (

Khaw et al. 2023).

Third, we did not apply a quality threshold for the literature sample, because we did not want to diminish it any further. Some scholars might argue that articles published in journals with low average citations per article, i.e., with a low average impact or relevance, should be avoided. However, the individual citation numbers of specific articles are more important than the average citation numbers of journals—most articles are cited much more often or less often than the average citation numbers of the journal they were published in. Additionally, we did not find any further signs that clearly indicated that they should be excluded when we reviewed the articles. After all, our goal was to identify as many curriculum items as possible, and no item that we found was unreasonable.

Fourth, our findings represent only the research perspective and not the teaching practice perspective on entrepreneurship curricula, as they are based on a systematic literature review. Previous EE research could have focused on specific curriculum items due to individual research interests or the intellectual support of these items, whereas teaching practice might look different. To assess the reality of entrepreneurship education, analyses of existing curricula have to be conducted (

Seikkula-Leino 2011;

Tiberius et al. 2023). In addition, future research should also address ways to improve EE from educators’ and entrepreneurs’ perspectives.

Despite these limitations, our review contributes to entrepreneurship education research and especially to entrepreneurship curriculum research in several ways. First, it provides a comprehensive overview of all entrepreneurship curriculum items in the four dimensions of objectives, contents, teaching methods, and assessment methods that have been subject to curricular research so far. Whereas the individual items that have been identified through this review cannot be considered novel or unexpected, their compilation represents the current state of research.

Second, this review distinguishes between genuinely entrepreneurship-specific items and those related to business management, which are often not clearly separated. Third, even though the law of large numbers does not apply to our review, the numbers for how often the items were mentioned provides an impression on the (mainly low) research intensity in the curriculum dimensions. In particular, it shows room for improvement, especially in the teaching method and assessment method dimensions.

The findings also have practical implications. The compilation of curriculum items can be used by entrepreneurship educators and curriculum designers for entrepreneurship programs. As mentioned before, entrepreneurship programs need to be evaluated on a regular basis. For this, it is necessary not only to measure the impact of EE (outcome perspective) but also the pedagogy of EE itself (inside or process perspective) based on used curriculum items and the students’ approval.