Abstract

In recent years, a new type of influencer has emerged in the field of social media marketing: virtual influencers. Though it is spreading fast, the trend is still new and, therefore, limited research has been conducted on the topic. This study aims to investigate the impact of virtual influencers on customers and whether there is a direct impact on human influencers due to the rise of virtual influencers in the industry. The study employed a questionnaire-based survey method to collect and analyse responses from a sample of 357 participants. The questions focus on trust, credibility, expertise, and contribution to purchase intention by the virtual influencers. The results indicate that customers are increasingly attracted to virtual influencers and that virtual influences are perceived as more trustworthy, credible, and relevant to customers’ preferences, leading to an increase in purchase intention. The study also discusses the implications of these findings for managers designing marketing campaigns.

1. Introduction

Virtual influencers, also known as AI-generated influencers or digital avatars, have been on the rise in the marketing industry. These computer-generated characters or digital models are designed to look and act like real people and have their social media profiles and post content that marketers, agencies, or studios create. Using virtual influencers has become an effective way for brands to connect with and engage with their customers on social media platforms (Brown and Hayes 2008). These virtual influencers have realistic characteristics and features like human personalities (Moustakas et al. 2020). The use of virtual influencers for promoting products on social media has become an intriguing trend. One of the primary reasons for their appeal is their perceived high level of reliability and predictability compared to human social media influencers. It is worth noting that human influencers can occasionally exhibit irrationality and bias, while virtual influencers are governed by underlying algorithms that can be fine-tuned to suit the needs of the brand. This, in turn, provides brands with greater control and authority over their sponsored content. Therefore, virtual influencers have emerged as a more cost-efficient alternative to human social media influencers (Thomas and Fowler 2020). However, little is known about the impact of virtual influencers on consumer behaviour, specifically in terms of perceived trust, purchase intent, and preference of the customers towards virtual or human influencers. Since influencer marketing studies are majorly focused on human influencers, little research has been published about virtual influencers’ effectiveness.

Virtual influences are system-made versions of social media influencers that can take any shape, style, or size after that matter-of-fact personality (Lewczyk 2021). Primarily, these virtual influencers are created using artificial intelligence technology, and there is much human effort involved to decide the looks, posts, and the way of interaction of these virtual influencers.

A noteworthy aspect of virtual influencers is their absence of physical limitations related to time and space. Unlike their human counterparts, they do not experience fatigue or require rest, are not subject to the ageing process, and do not face the inevitability of death (Matthews 2021). Virtual influencers can pursue their interests without incurring any real-life expenses, rendering them more cost-effective in the long run. Moreover, virtual influencers are not susceptible to the controversies or scandals that may plague their human counterparts, further solidifying their appeal to brands seeking a reliable and low-risk influencer marketing strategy. Companies’ utilisation of social media influencers has led to a rise in consumer purchase intention (Jiménez-Castillo and Sánchez-Fernández 2019). This phenomenon is attributed mainly to the influencers’ ability to engender trust and a sense of similarity with the target audience, thereby strengthening their impact on purchase intention. This is consistent with the findings of Jiménez-Castillo and Sánchez-Fernández (2019), who also investigated the positive impact of social media influencers on consumer purchase decisions.

In contrast, Hirschmann’s (2021) research on virtual influencers revealed that 60% of the respondents from Singapore did not perceive any influence on their purchase decisions by virtual influencers. Per the respondents’ opinions, human social media influencers significantly impacted their purchase decisions more than virtual influencers. This research aims to investigate and establish the relationship between the emergence of virtual influencers and consumer behaviour around them. Based on the author’s previous influencer research, an evolution from macro-influencers to micro- and nano-influencers to virtual influencers seems to happen. During a literature review exercise, it was found that this topic has been sparsely researched, and only a handful of studies are available. That gave the author impetus to work on the subject and contribute to the existing literature to benefit industry and fellow academicians.

1.1. Research Objectives

It is imperative to establish research objectives at the outset of a study to establish the purpose of the research and guide the researcher’s efforts throughout the investigation. As such, the research objectives outlined below are intended to shape and direct this study:

- RO1: To scrutinise the degree to which virtual influencers are perceived as trustworthy by consumers in the context of social media marketing.

- RO2: To explore the association between trust in virtual influencers and purchase intention among consumers.

- RO3: To identify the underlying factors that shape trust and purchase intention towards virtual influencers in social media marketing.

- RO4: To compare and contrast consumer preferences for virtual versus human influencers, focusing on their impact on trust and purchase intention.

Based on these research objectives, research methodology and data collection strategies have been framed and discussed in the upcoming sections.

1.2. Research Significance

This study aims to scrutinise the degree to which consumers perceive virtual influencers as trustworthy, explore the association between trust in virtual influencers and purchase intention, identify the key factors that shape trust and purchase intention towards virtual influencers, and compare consumer preferences for virtual versus human influencers. A mixed-methods approach was employed to achieve these objectives, consisting of an online survey with open and closed answers. The results of our research will yield significant insights into the influence of virtual influencers on consumer behaviour, with a particular focus on the extent to which they engender trust, influence purchase intention, and shape preferences for virtual versus human influencers. These findings will prove instrumental in guiding marketing strategies for brands that leverage virtual influencers. They will also make a valuable contribution to the academic literature on virtual influencers and their impact on consumers.

2. Literature Review, Terms, and Interpretations

To ensure clarity and precision in this study, it is necessary to define key terms used in the research. Some of the terms that will be actively used in this study include:

Purchase intention: In this study, purchase intention is defined as the probability or likelihood of a consumer making a purchase. As noted by Hsu et al. (2013), consumers frequently consult social media for guidance before making purchase decisions, increasing the likelihood of purchase. This trend can be attributed to social media influencers’ perceived trustworthiness and similarity to the target audience. Additionally, Jiménez-Castillo and Sánchez-Fernández (2019) have established a direct relationship between influencer–consumer relationships and purchase intention.

Brand trust: In the context of this study, trust pertains to the confidence consumers possess regarding a brand’s capability to deliver performance according to situational expectations. As stated by Chaudhuri and Holbrook (2001), brand trust plays a crucial role in fostering repeat customers and inculcating long-term usage and purchase loyalty. Trust represents a fundamental element in forging enduring customer relationships and is widely considered an indispensable component of any brand.

Customer engagement: Customer engagement is the degree of involvement and interaction with a brand and other community customers through messaging and content sharing on various platforms. This multidimensional construct includes affective, cognitive, and behavioural dimensions outlined by Vivek et al. (2012). Numerous scholars have conceptualised customer engagement, all of whom have recognised that it generates observable behavioural outcomes and predicts customer behaviour.

Virtual influencers: Virtual influencers are computer-generated virtual personalities created to amass a considerable following on social media platforms. Despite the common perception that AI entirely controls these influencers, there is always an element of human supervision and partial control involved. Despite their virtual nature, these influencers are perceived as authentic and credible brand ambassadors, comparable to social media influencers (Moustakas et al. 2020). Consequently, it is unsurprising that virtual influencers can influence their followers and customers, positively impacting brand outcomes.

Virtual influencers have emerged as a recent research subject due to their growing popularity. Kádeková and Holienčinová (2018) explored the potential of virtual influencers to attract customers and influence their purchasing decisions while also considering them as a sub-genre of traditional influencers. The authors concluded that virtual influencers have certain advantages, such as being controllable, adaptable, and able to align with campaign objectives. However, they also highlighted several underlying risks, including moral principles, transparency, credibility, and overall trustworthiness concerns. Consumers may question the authenticity of virtual influencers due to their lack of reality and limited cognitive abilities. Conversely, human influencers pose a risk due to their potential personal agendas. Thus, using influencers, whether virtual or human, involves a complex set of advantages and disadvantages that brands must carefully weigh.

Moustakas et al. (2020) conducted a study similar to Kádeková and Holienčinová (2018), where they interviewed six digital media experts to gain insights and perspectives on the use of virtual influencers in marketing campaigns, as well as their potential advantages and disadvantages. The authors concur with Kádeková and Holienčinová (2018) that virtual influencers can be fully controlled, tailored to fit campaign objectives, and are not influenced by personal agendas. However, they add an ethical dimension to the debate, questioning the propriety of allowing people to form relationships with virtual influencers that are not real. The author further highlights that authenticity, transparency, and reliability may be questionable since virtual influencers are driven purely by commercial objectives. Moreover, the experts identified Generation Z and millennials as the most suitable target market for virtual influencers. The study also sheds light on the uncertainties surrounding the success of virtual influencers and the substantial investments required to create and ramp up the technology framework. Finally, the authors discuss parasocial relationships and their contribution to developing a stronger bond between avatars and humans.

This presents an opportunity to delve deeper into the theoretical foundations that could underpin the relationship between avatars and humans and their impact on purchase decisions. Some of the theories and concepts that emerged as intriguing during the literature review include:

- Source Credibility Theory is a theoretical framework that explains the relationship between communication persuasiveness and the credibility of the communication source. It was first studied by Hovland et al. (1953), who examined the audience’s attitude towards messages received from communicators. According to them, the communicator needs to have a persuasive effect on the receiver, which makes the communicator a credible source of information. They further suggested that the communicator’s credibility depended on two factors, namely, the trustworthiness and expertise of the communicator. The theory has also been used as a guiding tool to examine the concepts of parasocial relationships and opinion leadership in this research work.

- The Concept of Parasocial Relationships, first introduced by Horton and Wohl (1956), describes an imaginary relationship between the audience and a media persona through a mediated encounter. This subjective feeling of being part of a personal, reciprocal, and immediate social interaction with the media persona is a one-sided relationship in which the audience tends to imagine the media person as their friend. Chung and Cho (2017) have defined three attributes that incite parasocial relationships: friendship, understanding, and identification. Friendship includes intimacy and liking with the media person, understanding refers to the followers’ feelings towards the character, and identification refers to the adoption of similar interests, behaviours, and traits of the media person. Parasocial relationships have been studied concerning opinion leadership and the impact of virtual influencers on consumer behaviour.

- The Concept of Opinion Leadership, based on a two-step flow communication model, was first introduced by Lazarsfeld et al. (1944). According to this model, content from mass media is first consumed by opinion leaders who actively collect, interpret, and diffuse the information to the broader public. Interpersonal interactions play a crucial role in disseminating information from opinion leaders to mass consumers. These opinion leaders tend to reinforce their opinions through consensual validation with others.

- The Uncanny Valley Theory suggests that virtual influencers may evoke feelings of discomfort, unease, and mistrust among customers due to their unrealistic, nonhuman appearance. Studies have shown that human faces are generally perceived as more appealing and trustworthy than nonhuman faces. Arsenyan and Mirowska (2021) investigated the reactions of virtual influencer followers using the Uncanny Valley Theory and found more negative reactions among them compared to followers of animated or human influencers. Block and Lovegrove (2021) have argued that the persuasiveness of virtual influencers depends on their level of humanness, with more human-like virtual influencers having a more substantial impact on persuasion. Lu from MegaLu is a prime example of a virtual influencer who effectively uses her uncanniness and fascination to persuade her followers.

In contrast, Stein et al. (2022) examined viewers’ parasocial responses to the ontological nature of the influencer and found no advantage of humans over virtual online personas. However, the authors noted that the observations could have been influenced by the novelty effect, a bias stemming from the newness of the concept of virtual influencers. This effect may have resulted in respondents feeling intrigued by the depicted character, thus exhibiting a stronger inclination towards virtual influencers. The current study should be interpreted with this in mind, recognising that perceptions may have played a role in the recorded responses.

2.1. Role of Credibility

Each marketing campaign is designed to achieve a positive attitude towards the brand and advertisement. Past studies have focused on the influence of the personal attributes of the endorsers and their persuasiveness on the overall effectiveness of the campaigns. Hovland et al. (1953) commented that the receiver’s perception of the credibility of the source of information greatly influences the purchasing decision and the marketing campaign’s effectiveness. Several other researchers, including Lou and Yuan (2019) and Kapitan and Silvera (2016), have also mentioned the impact of attractiveness, trustworthiness, and expertise in the overall marketing campaign. They used experimentation with an athlete to conclude that, if the consumer has a positive perception of the athlete’s attractiveness, trustworthiness, and expertise, then it is highly likely that the consumer would try the product endorsed by the athlete at least once. Thus, a message’s effectiveness has been found to be more significant when the endorser’s credibility is higher.

2.2. Role of Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness, in the context of this study, is defined as the level of confidence and trust that the audience has in the endorser when they deliver the message, according to Amelina and Zhu (2016). Confidence is crucial in establishing trust between the communicator and the receiver. It is a necessary precursor to trust. For mutual trust to exist, the audience must perceive the message as authentic and unbiased. Chung and Cho (2017) also support this idea.

2.3. Impact of Expertise

The dimension of expertise refers to the extent to which an individual possesses the knowledge, skills, or experience to convey reliable information on a given topic (La Ferle and Choi 2005). When an audience is presented with a cue highlighting an endorser’s expertise, it enhances their perception of the endorser’s competence (Amelina and Zhu 2016). For instance, employing a soccer player as an endorser for cleats would promote the cleats as the player is considered an expert in the sport. A meta-analysis by Amos et al. (2008) revealed that expertise is critical in boosting an endorser’s persuasiveness. Numerous studies have shown that endorsers perceived as highly competent can influence consumers’ attitudes towards advertisements, brands, and purchase intentions. In light of these findings, research has examined consumers’ perceptions of a virtual influencer’s knowledge. The study suggests that virtual influencers may not be regarded as experts because brand managers must fabricate the qualities of the virtual influencer. Thus, it is vital to determine whether competence and trustworthiness are potential metrics for assessing virtual influencers. Understanding whether consumers evaluate virtual influencers based on expertise and trustworthiness is essential. It reveals the cognitive processes they employ to evaluate the endorsement, such as internalisation for expertise and trustworthiness and identification for attractiveness. Alboqami (2023) tried to analyse the high trust of consumers in VI and identified how source attractiveness (i.e., physical attractiveness and homophily), source credibility (i.e., expertise and authenticity), and congruence (i.e., influencer, customer, and product) form relevant patterns.

2.4. Purchase Intention

In studies examining the effectiveness of endorsers, purchase intention is often a key variable (McCormick 2016). Purchase intention refers to a consumer’s subjective evaluation of a product or service, following a broader assessment of its attributes (Balakrishnan et al. 2014), indicating the likelihood of making a purchase. The primary objective of a marketing campaign is often to persuade customers to use a product or service, leading to a decision to purchase. Advertisements act as a mechanism to transfer meanings from the endorser to the endorsed product, which consumers accept (McCracken 1989), as stated in the MTM. Several studies have demonstrated that virtual influencer endorsements will likely increase purchase intention. Therefore, the present study aims to expand upon and quantify these findings by exploring the parameters of trustworthiness, credibility, expertise, relevance, and impact on purchase intention. The questionnaire was designed to capture the respondents’ responses, paving the way for further analysis. However, the relevance of endorsement has not been extensively discussed in the reviewed studies. Thus, the current study’s contribution to the research community lies in exploring the impact of virtual influencers as endorsers, including their relevance as a critical parameter.

Drawing upon these concepts and theories, a comprehensive framework can be developed to understand the impact of virtual influencers on consumer behaviour. The source credibility theory asserts that the influencer must be perceived as credible and persuasive by the audience. The concept of parasocial interaction and opinion leadership is also relevant in the context of virtual influencers as they are based on the audience’s perception of the influencer’s trustworthiness and expertise. For instance, the audience must perceive the influencer as trustworthy for both parasocial relationships and opinion leadership to develop (Gerlich 2023). Similarly, the concept of expertise is linked to opinion leadership as it is based on attributes such as competence, knowledge, skills, and experience. However, opinion leadership cannot be considered in isolation, as the development of valid assertions by the influencer also depends on the formation of parasocial relationships. Therefore, the source credibility theory, parasocial interaction, and opinion leadership collectively constitute the framework for assessing the impact of virtual influencers on consumer behaviour.

2.5. Virtual Influencers

The influencer marketing industry has been undergoing continuous innovation, leading to the emergence of numerous virtual influencers. While these virtual influencers share human-like traits, they do not correspond to any human in the real world. Companies are generally discreet about the software or technology employed in creating virtual influencers. Typically, brands generate a 3D rendering of a character or avatar resembling an influencer or celebrity and subsequently use programming and software to animate the character and enable interactions with the environment or actual people. Brands leverage virtual influencers to create content and campaigns, distribute them across social media platforms, and engage their target audience.

The emergence of virtual influencers dates back to the early 1990s, when cartoon characters were first introduced. The first virtual celebrity and idols were launched in Japan, which paved the way for virtual YouTubers or V-tubers, fictional characters that create content and engage with audiences on YouTube. Kizuna AI, a popular V-tuber with over three million subscribers, is an example of the appeal of virtual influencers in influencer marketing. Li Miquela, launched in 2016, became a successful virtual influencer, inspiring the launch of several others. Virtual influencers have been found to be more attractive than real ones, leading to their increased popularity (Sands et al. 2022). Below is a list of the top brands with their virtual influencers and social media penetration. This list has been compiled from various social media pages and articles (Table 1).

Table 1.

Leading virtual influencers.

Anthropomorphising is a crucial characteristic shared by virtual influencers, referring to how much an image resembles a human. According to Miao et al. (2021), around 70% of publications suggest that anthropomorphic depiction is crucial in creating virtual characters, providing clues about their social lives. This is consistent with the uncanny valley theory, which states that an anthropomorphic virtual character is more likely to be perceived as trustworthy and credible. Moreover, consumers interact with human-like objects differently than they do with lifeless ones, as they tend to ascribe societal rules to them, despite being aware that they are interacting with a machine.

The impact of virtual influencers on consumers is multifaceted. By featuring virtual influencers in their campaigns, brands can expand their reach, increase visibility, and personalise the consumer experience. This approach provides an authentic message, creates an emotional connection, encourages engagement, and fosters relatability and trust, ultimately increasing brand loyalty. Virtual influencers offer greater flexibility in content creation than human influencers. They can be customised to fit the brand’s desired image and message for specific audiences, such as different cultures, genders, or age groups. Consumers are typically aware that virtual influencers are used in these campaigns, as brands clearly indicate their use through an introduction video or caption and through the virtual influencer’s visuals. Hashtags and other messaging strategies are also often used to educate audiences about the use of virtual influencers in these campaigns.

Notably, while some virtual influencers rely heavily on artificial intelligence, others still require human input. However, AI is expected to operate virtual influencers in the coming years fully. The various controlling entities involved in virtual influencers (whether human or AI) also present unique perspectives for researchers (Nowak and Fox 2018), which can influence how digital influencers are classified as bots or avatars. Typically, avatars are assumed to be AI-enabled and often perceived by consumers as possessing some level of intelligence, even though they may not be aware of the exact controlling entity behind the virtual influencer. Miao et al. (2021) have defined avatars as digital entities with anthropomorphic characteristics capable of interaction and controlled by either humans or software.

For many businesses, the influencer-related solution included robotics. Oliveira and Chimenti (2021) investigated how nonhuman influencers affected marketing communication and proposed five categories that might help management choices and future research on VIs: anthropomorphism/humanisation, attractiveness, authenticity, scalability, and controllability. This study also found more convergences than divergences across the virtual and actual worlds and between humans and nonhumans. The writers stated that attractiveness is inherent in influence, whereas having some genuine or perceived appeal, such as ability, beauty, style, humour, sensuality, or authority to draw attention is undoubtedly required. It is likely that qualities such as value creation, innovation, and exclusivity, among others, contribute to something appealing. This study identified an unattainable perfection in VIs and highlighted hazards to certain followers’ mental health because of unfeasible comparisons. A highly engaging story and an advanced visual, which provide feedback between attractiveness and scalability, are said to improve engagement in general further. A robust algorithm for a weak story does not appear to be perfect effectiveness, which raises the possibility of a link with a different category: authenticity.

Authenticity is related to reliability, dependability, and openness. It relates to the connection between the influencer and his fans, the narrative coherence of the influencer, and the link between the influencer and the marketers (Torres et al. 2019). According to Oliveira and Chimenti (2021), the plausibility of linear logic does not appear to be correlated with the authenticity and ethics of VIs. Arguments that virtual robots do not exist and cannot be authentic are often used when people are questioned. Multiple instances of exploitation motivated by apartheid have been documented. In a discussion like this, determining the profiles’ actual level of authenticity, if any, might be challenging. While important, the conversation about control, ownership, and authenticity seldom takes centre stage in VIs’ profiles and appears to lack maturity. The story’s strength appears to be one of the additional crucial factors. The author concluded that it is unclear what the precise value of authenticity is in the virtual world and what other factors (such as attractiveness, identification, value generation, etc.) might supplement or even supplant authenticity in online relationships with humans and nonhumans. In any event, the demand for control might be mistaken for authenticity (the more authentic, the more trustworthy/controllable), which calls for additional research.

De Brito Silva et al. (2022) conducted yet another investigation on the subject. They had made an effort to comprehend the influencer marketing method used by avatars that appeared to be human. The study’s primary goal was to comprehend how followers and avatars develop a relationship that lends credibility and authenticity. They contend that avatars are influential brand ambassadors who increase interaction through various tactics, from humanisation to robotisation and metaverse. According to each type of avatar, the authors found and studied the content and post forms that create higher and lower interaction. They concluded that, although being autonomous digital entities, avatar influencers serve as extensions and reflections of their followers’ identities inside a particular virtual world. Their life experiences and developed personas represent the general population who, consciously or subconsciously, decided to follow them as opinion leaders. The authors found that, although being controlled by a business, avatar influencers are powerful spokespersons with much potential for connecting with their audience. The lack of reality distinguishing avatar influencers from real people may limit the latter’s capacity to shape followers’ opinions and influence them. However, based on their findings, it would appear that, since avatars do not exist in the actual world, this makes them even more intriguing and alluring.

As a consequence, they may offer unique interactive experiences that pique people’s interest and enthusiasm. The authors recognised these qualities as components that make up the attractiveness sphere of avatars. These qualities include novelty and originality. The contents of approaching what is human, the evolution towards the human, or the transparency of her/his nonexistence in the world of atoms bring novelty and originality. De Brito Silva et al. (2022) also concluded that the congruence of their posts (with and without endorsement) with their lifestyle, personality, and narrative of their personal stories is the key to generating a connection between avatars and followers, conferring credibility and authenticity. Another theoretical contribution builds on the established spectrum of tactics, which spans from endorsing the nonhuman nature of the avatar to reinforcing it. Significantly, the choice of which tactic to employ relies on the reason why the avatar was created.

Additionally, Sands et al. (2022) gave insight into customer reactions to AI influencers. Although their findings indicate that people view AI influencers as less reliable, they discovered that there is no distinction between an AI and a human influencer for some outcomes. They discovered that consumers express stronger word-of-mouth (WOM) intentions for an AI influencer and are equally likely to follow either form of influencer. They said there is no difference in how personalisation is viewed, implying that an AI influencer has the same capacity to tailor material or suggestions as a human influencer. They said that this is a result of customers’ growing familiarity with AI recommendation systems, such as Netflix, which are thought to be able to learn from behaviour and provide intelligent suggestions. It is possible that this feature has to be highlighted by AI influencer developers as a crucial competitive advantage. Their findings give marketers the green light to experiment and add virtual AI influencers as brand ambassadors to their current influencer marketing plans. This might be especially useful for efforts to spread WOM. They demonstrated how artificial intelligence (AI) influencers could have higher WOM, which supports the World Health Organization’s choice to work with AI influencer Knox Frost in a COVID-19 campaign. If the employment of AI influencers may increase the spread of WOM, there may be repercussions for similar campaigns or public service announcements. In keeping with the advantages of VI, Sands et al. (2022) added that a brand may quickly develop an endless number of micro-targeted or even completely personalised influencers thanks to AI influencers. At the extreme, influencer bots that are specifically tailored to each customer may be used to target them all. The hyper-personalised offerings made by these individualised influencers may consider the customers’ preferences and even present them with an idealised image of themselves.

3. Research Hypothesis

Based on the review of the existing literature and the underlying theories, it looks likely that influencers have a particular impact on customers’ purchase intention. The expert opinion of the influencers does help in greater customer conversion for the brands. The trustworthiness and credibility of the brand further fuel this. While this is true for human influencers, it is assumed that a similar impact is seen for virtual influencers. That forms the entire hypothesis of the study, which is being tested using various statistical tests, as mentioned in the upcoming methodology section. This led to the following general research hypothesis:

Hypotheses for the Virtual Influencers Questionnaire:

Hypothesis related to trust in virtual influencers:

H1:

Customers perceive virtual influencers as more trustworthy compared to human influencers.

Hypothesis related to reliability of information:

H2:

Customers perceive the information provided by virtual influencers to be more reliable compared to human influencers.

Hypothesis related to purchase intention:

H3:

Customers have a higher purchase intention for products or services endorsed by virtual influencers compared to human influencers.

Hypothesis related to consideration in purchase decisions:

H4:

Customers give more consideration to the opinions of virtual influencers when making purchasing decisions compared to human influencers.

Hypothesis related to relevancy of opinion:

H5:

Customers perceive virtual influencers’ opinions to be more relevant to their interests and lifestyle compared to human influencers.

Hypothesis related to expertise on the matter:

H6:

Customers perceive virtual influencers to have more expertise on the subject matter compared to human influencers.

The relevant questions linked to each hypothesis are as follows:

- H1:

- Question 5 (Trust in Virtual Influencers);

- H2:

- Question 6 (Reliability of Information–Virtual Influencers), Question 7 (Reliability of Information–Human Influencers);

- H3:

- Question 9 (Purchase Intention–Virtual Influencers), Question 10 (Purchase Intention–Human Influencers);

- H4:

- Question 11 (Consideration in Purchase–Virtual Influencers), Question 12 (Consideration in Purchase–Human Influencers);

- H5:

- Question 16 (Relevancy of Opinion–Virtual Influencers), Question 17 (Relevancy of Opinion–Human Influencers);

- H6:

- Question 8 (Expertise on Matter–Virtual Influencers), Question 13 (Expertise on Matter–Human Influencers).

4. Methodology

To examine the impact of virtual influencers on overall product selection and purchase intention, a mixed-methods approach (Williams 2007) was utilised, comprising an online survey with five-step Likert-based scales and a series of open-ended questions to capture underlying reasoning. The survey was distributed via paid social media advertising on Instagram, Facebook, and LinkedIn to attract a sample of consumers who have interacted with virtual and human influencers on social media, collecting data on trust, purchase intent, preference, and demographic information. It was a self-selection (volunteer) sampling based on the reach of the social media platforms. Quantitative analysis was conducted on the numerical data, using statistical techniques to obtain objective insight. The study aimed to quantify the effectiveness of virtual influencer endorsements and compare consumer preferences for virtual and human influencers. The research sought to identify the degree to which virtual influencers influence consumers and their relationship to the attributes of influencer marketing.

4.1. Design and Procedure

Due to the topic’s novelty, the limited literature availability allowed for innovative and thoughtful inferences. The author prioritised information from peer-reviewed journals; equal weight was given to ongoing research, theses, as well as newspaper and online articles. Past and current research studies were included and, when direct data were unavailable, partially relevant information was used.

A few variables have been shortlisted after the literature review: trustworthiness, reliability, purchase likelihood, consideration of opinion, opinion relevance, and overall subject matter expertise. An online questionnaire was promoted via Instagram, Facebook, and LinkedIn from January to February 2023 to gather data on these variables. The samples generated using the online platforms, thus, are self-selection (volunteer) samples. The survey consisted of multiple-choice questions, with a clear distinction between parameters related to virtual influencers and human influencers. Responses were captured using a 5-point Likert scale, aiming for easy decision making and user-friendliness. To mitigate the risk of ambiguity, the questions were formulated straightforwardly. The survey began with a section devoted to collecting demographic information from respondents, including age, gender, location, and education level. This was followed by a series of simple questions designed to elicit responses to the abovementioned parameters. In addition, specific more in-depth questions were included to capture respondents’ opinions on the topic, such as:

- –

- Why do you trust/not trust virtual influencers?

- –

- Why are you more or less likely to purchase a product or service that is endorsed by a virtual influencer?

- –

- What are the demographics of the virtual influencer you know?

- –

- What are the reasons for your satisfaction or dissatisfaction with virtual influencers?

4.2. Data Collection

The online survey received 613 responses, of which 357 were deemed complete and legitimate for analysis. The sample size for this research is based on these 357 responses. Respondents from 18 different countries participated in the survey, and their demographic and descriptive statistics are presented in the following section.

4.3. Data Analysis

The data collected from the online survey has undergone statistical analyses such as descriptive statistics, chi-squared tests, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) to examine the differences in trust, purchase intent, and preference towards virtual or human influencers (Henson 2015). Descriptive statistics provide an overview of the data using central tendency and variability measures. Subsequently, a chi-squared test has been conducted to examine the relationship between variables such as gender, geography, and education level and the reasons for being influenced. On the other hand, ANOVA has been used to compare the variances between human and virtual influencers concerning influence, purchase intention, trustworthiness, and similarity in taste and lifestyle.

Ordinal regression is another statistical analysis method conducted in this study (Liu and Koirala 2012) Ordinal regression is a statistical technique to model one or more independent variables with an ordinal dependent variable. This technique is used when the dependent variable is measured on an ordinal scale, meaning the values are ranked in a specific order. This analysis aims to predict the behaviour of dependent variables at the ordinal level using a set of independent variables. In this study, ordinal regression was performed on the dependent variable of choosing virtual influencers over human influencers, with the parameters of virtual influencers and the parameters of both virtual and human influencers used as independent variables. Control variables such as age, gender, and education were also included in the analysis. Another ordinal regression analysis used virtual influencer satisfaction levels as the dependent variable, with reliability, relevance, expertise, trust, consideration, and likelihood of purchase as independent variables. The control variables for this analysis were the same as in the previous analysis.

5. Analysis and Discussion

The next step in the research is to analyse the data collected through questionnaires. A total of 357 responses have been recorded as complete and legitimate for analysis. The first step in the analysis would be to examine data distribution based on demographic characteristics.

6. Demographic Analysis

To maintain the integrity and validity of the research, the questionnaire was not targeted at respondents from any particular country. The responses were received from a total of 357 participants with diverse backgrounds. It can be noted that countries such as Singapore, Japan, and the US are known for their high levels of internet and digital technology adoption. Additionally, these countries are home to some of the world’s most prestigious universities and academic institutions, which attract a large student population. Therefore, it is possible that the high response rate from these countries may be due to a combination of higher internet penetration and a higher concentration of students who are more likely to participate in online surveys.

The age of the respondents plays a critical role in analysing the responses to the questionnaire. Since virtual influencers are more popular among the millennial population, it is interesting to see the responses from millennial versus non-millennial populations. It is also essential to take the perspective of both male and female respondents towards virtual influencers to remove any gender biases. It was seen that roughly 50% of the population under scrutiny falls below the age of 45, with the other 50% comprising individuals above this age threshold. Additionally, a nearly balanced distribution of male and female respondents is observed, with 183 males and 174 females participating in the survey. Such a distribution negates the potential for bias or skewness towards a particular age or gender cohort, thereby rendering the collected data well dispersed across demographic variables.

Approximately 45% of the total respondents have attained a minimum of a graduate degree, signifying that they possess a basic understanding of consumer behaviour, preferences, and marketing concepts. Additionally, approximately 20% of respondents are high school graduates, yet belong to the millennial population who are well versed with the various social media platforms and the tactics used in social media marketing. Thus, the distribution of respondents across different education levels obviates any potential biases or skewness in the results attributable to differences in educational background.

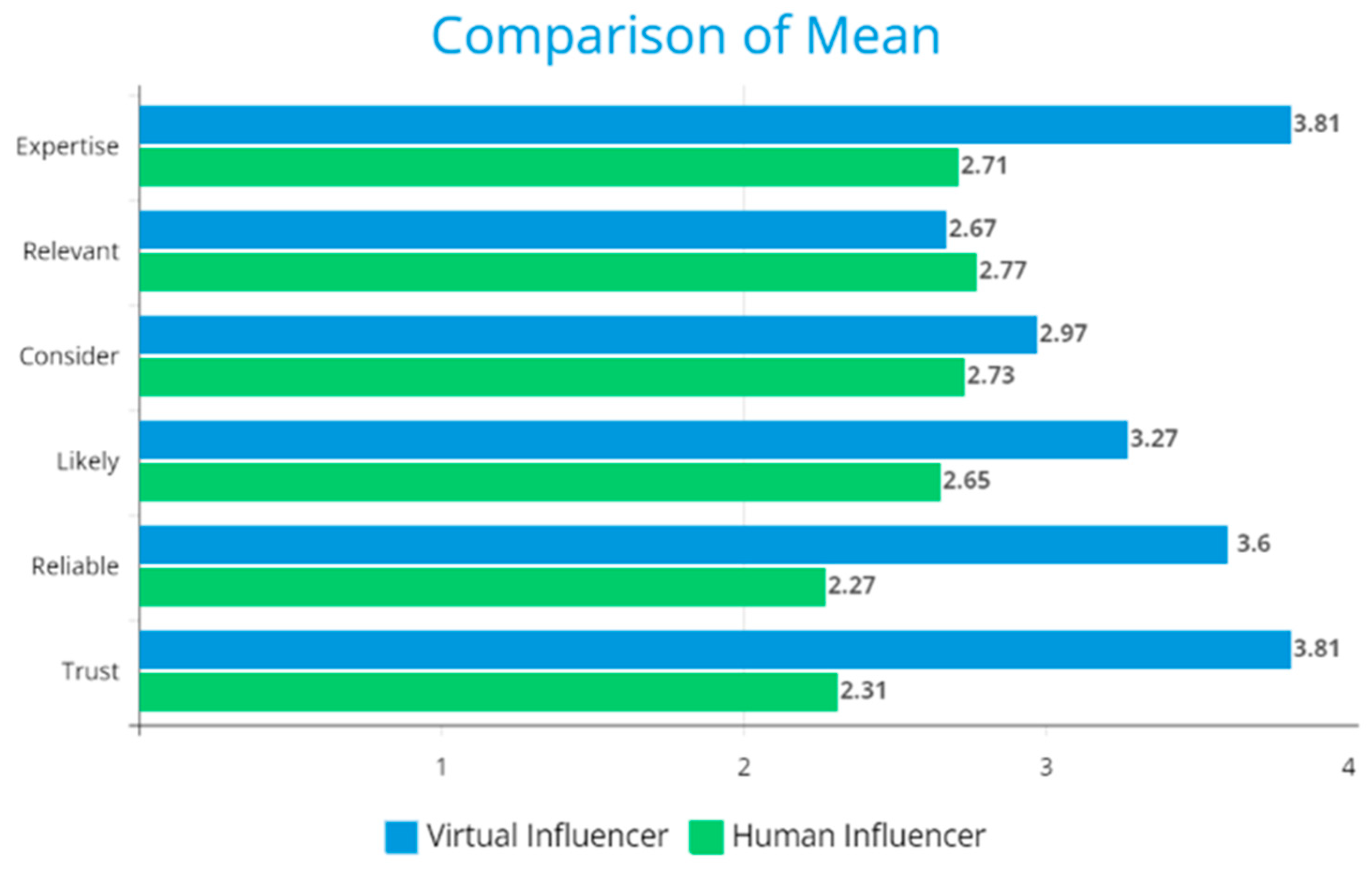

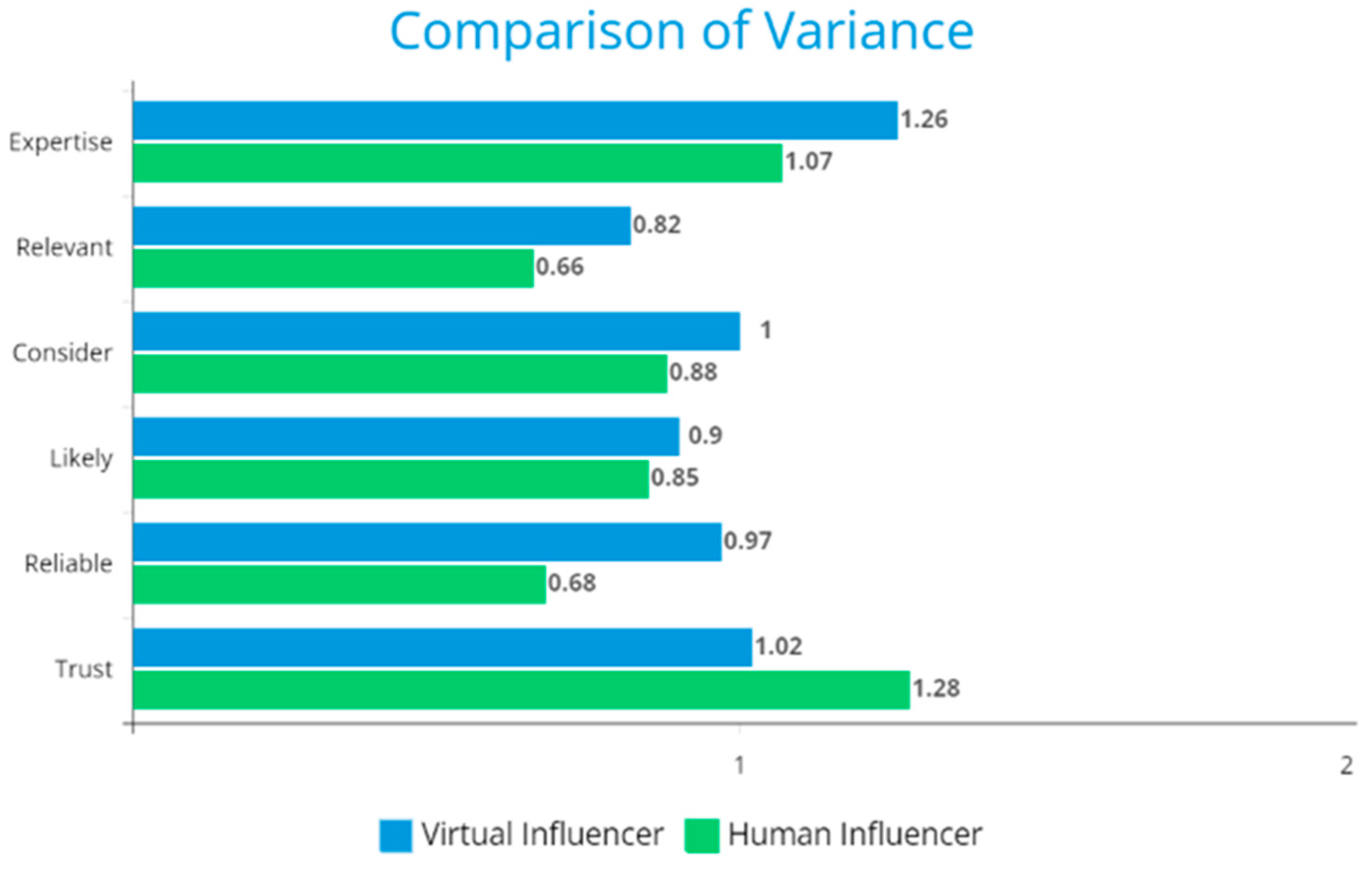

After concluding the demographic distribution analysis, the subsequent step involved performing a descriptive analysis. The descriptive analysis was conducted on specific questions of the questionnaire that do not contain subjective answers or demographic information. These questions were designed to capture the consumers’ preferences regarding various parameters for virtual and human influencers. The statistics are based on the responses provided in the form of a Likert scale, where a rating of 1 refers to the lowest and 5 refers to the maximum rating. The mean and variance statistics for various parameters have been tabulated below (Table 2).

Table 2.

Descriptive stats for human and virtual influencers.

The descriptive statistics (Figure 1 and Figure 2) show that the mean score for virtual influencers is higher than for human influencers across all parameters. This suggests that virtual influencers are gaining traction in social media marketing and are gradually gaining consumers’ trust. The mean scores for trust, reliability, and expertise on the subject are particularly encouraging, with scores ranging from 3 to 4. In contrast, the mean score for human influencers is below average across all parameters, with the lowest score for reliability. This may be because human influencers often endorse products based on their own commercial interests and marketing benefits rather than the quality of the product itself. Gerlich (2022) explored this argument in great detail. The low variance in responses for human influencers indicates rating them poorly consistently. The only parameter in which human influencers were rated higher was the relevancy of their opinions, but this may be due to the trending nature and fine-tuning of artificial intelligence engines.

Figure 1.

Comparison of mean.

Figure 2.

Comparison of variance.

6.1. Statistical Significance of the Sample Size

A sample must be representative of the population. A more significant than necessary sample size will be more accurate since it will be more representative of the population. Beyond a certain threshold, the accuracy gain will be marginal and will not be worth the time and money spent contacting further respondents. This is often determined numerically as the sample size needed in hypothesis testing research, with P for statistical significance set at 0.05, to be 80% certain of discovering a statistically significant result should the hypothesis be valid for the population. Some researchers power their experiments at 90% rather than 80%, and some choose a 0.01 significance level rather than a 0.05 threshold.

In this research study, a significance level of 95% has been the aim. The following formula has been used to calculate the significance of the population level with 357 participants and a 5% margin of error level:

Necessary Sample Size = [(z-score)2 * std dev * (1 − std dev)]/(margin of error)2

Assuming a population size of 100 million (internet users across the targeted nations), a targeted 95% confidence level (z-score—1.96), and a standard deviation of 0.5, the necessary sample size is 384. In our research, the sample size is 357; therefore, it can be safely stated that the significance level of the sample size is somewhere between 90% and 95%.

6.2. Perceptions and Behaviour

To further understand the perception and behaviour of the respondents towards virtual influencers, an analysis was conducted on those who had no prior interaction with virtual influencers. An interaction for this study is defined as an active act of the participant, such as a comment on social media, a like, or any other activity with a virtual influencer or their accounts. Out of the 357 responses received, 124 indicated that they had no direct interaction with virtual influencers. Despite this lack of interaction, they still had perceptions about virtual influencers and their responses were based on those perceptions. The mean results of those 124 responses can be seen in Table 3.

Table 3.

Analysis of mean considering interaction with virtual influencers.

From the analysis, it is clear that, even though the respondents have not directly interacted with virtual influencers, they positively perceive them. This positive perception is reflected in the high mean scores of all the parameters, with some even surpassing the overall mean score. This indicates that virtual influencers are perceived positively, and these perceptions can significantly influence the customers’ trust, reliability, relevance, and expertise towards virtual influencers. Ultimately, these perceptions can impact the customers’ purchasing behaviour.

Upon a deeper analysis, it can be observed in Table 4 that the count of strongly disagree and strongly agree responses for almost all the parameters reflects highly positive perceptions held by the respondents. This trend is consistent across the parameters of trust, reliability, likelihood of purchase, consideration of opinion, relevancy of opinion, and overall expertise.

Table 4.

Extreme responses from participants who did not interact with virtual influencers yet.

Despite the lack of direct interaction, this phenomenon of positive perception towards virtual influencers warrants further investigation as a standalone research topic to delve deeper into customer behaviour and attitudes towards virtual influencers.

It is anticipated that the relevancy of opinion for virtual influencers will increase compared to human influencers once the engine fully synchronises with the target audience’s preferences. To verify the robustness of the findings, a chi-square independence test was conducted to assess whether the responses were associated with the sample’s demographic characteristics. The chi-square test of independence is a statistical tool that enables researchers to draw inferences about a population based on a representative sample (Tallarida and Murray 1987). It enables the detection of associations between two variables in the population, indicating that their responses may differ across various categories such as gender, age, and location.

H0:

Demographics and the theme for being influenced are not related in the population; the proportion of responses within the category is the same for all themes.

H1:

Demographics and the theme for being influenced are related in the population; the proportion of responses within the category is not the same for all themes.

The results of the chi-square test for demographic segmentation of responses are tabulated in Table 5.

Table 5.

Chi-square test for demographic segmentation.

As none of the p-values for the test were found to be less than 0.1, indicating that none of the values were significant at a 90% significance level, the null hypothesis cannot be rejected. Thus, it can be inferred that the responses across the population will be the same in each category, indicating that the current sample size is a reliable indicator of the population and the conducted tests are a valid representation of the overall preferences of the population. Moving forward, the next step in the methodology is to analyse variance (ANOVA), a statistical technique used to analyse the differences between two or more data groups. ANOVA tests whether the means of two or more groups are significantly different from each other. The hypotheses for the ANOVA test are:

H0:

The impact of parameters such as brand trust, expertise, relevancy of the suggestions, and the consideration of suggestions is the same for all influencers on purchase intention. There is no difference in the level of impact of these parameters for virtual and human influencers.

H1:

The impact of parameters such as brand trust, expertise, relevancy of the suggestions, and the consideration of suggestions is not the same for all influencers on purchase intention. There is a definite difference in the level of impact of these parameters for virtual and human influencers.

With this hypothesis in the backdrop, the ANOVA single-factor test (Haase 1983) has been conducted in Table 6.

Table 6.

ANOVA single-factor test.

As depicted in the table, the p-value for the analysis of variance between groups is close to zero, indicating a significant impact of parameters such as brand trust, expertise, relevancy of suggestions, and consideration of suggestions on overall purchase intention. Companies should prioritise developing and maintaining these parameters to gain a competitive advantage in social media marketing campaigns. Focusing on these parameters can result in successful social media marketing campaigns for companies. The empirical research shows that virtual influencers are rated higher on parameters such as trust, reliability, and expertise when compared to human influencers, and they have a greater impact on customers’ purchase intention.

The last step of the methodology is to conduct an ordinal regression. Three ordinal regressions have been carried out as a part of the analysis:

- Regression 1

Dependent variable: consumers prefer virtual influencers over human influencers;

Independent variable: parameters of virtual influencers—trust, reliability, relevance, expertise, the likelihood of purchase, and consideration of opinion;

Control variable: age, gender, and education.

H0:

The virtual influencer parameters have no impact on people’s choice of virtual influencers over human influencers.

H1:

The virtual influencer parameters impact people’s choice of virtual influencers over human influencers.

Table 7.

Model fitting (I).

Table 8.

Goodness of fit (I).

Table 9.

Pseudo R-square (I).

Based on the results presented in Table 7, it can be observed that the P value for model fitting parameters is 0.014, which is less than the critical value of 0.05, indicating the statistical significance of the model fitting parameters. Thus, the null hypothesis can be rejected, and it can be inferred that the independent variables, such as trust, reliability, etc., for virtual influencers significantly impact consumers’ choice of virtual influencers over human influencers. This hypothesis is further supported by the Pearson value of goodness of fit (Table 8), which is greater than 0.05, suggesting that the data set is significant, and the independent variables contribute to the final output of the dependent variable. Moreover, the table of pseudo R-square (Table 9) highlights the proportion of the variance explained by the independent variables on the dependent variable in the regression model. Notably, the values of these parameters are less than 0.7, indicating that the proportion of variation can be explained. Hence, this model is considered a good fit for the purpose.

- Regression 2

Dependent variable: consumers prefer virtual influencers over human influencers;

Independent variable: parameters of virtual and human influencers—trust, reliability, relevance, expertise, the likelihood of purchase, and consideration of opinion;

Control variable: age, gender, and education.

H0:

The virtual and human influencer parameters have no impact on people’s choice of virtual influencers over human influencers.

H1:

The virtual and human influencer parameters impact people’s choice of virtual influencers over human influencers.

Based on the similar arguments, it can be inferred that the results (Table 10, Table 11 and Table 12) are significant and, hence, the null hypothesis can be rejected.

Table 10.

Model fitting (II).

Table 11.

Goodness of fit (II).

Table 12.

Pseudo R-square (II).

Another regression has been performed on testing the role of virtual influencer parameters on the overall virtual-influencer-related satisfaction level of the consumers.

- Regression 3

Dependent variable: satisfaction level of consumers with virtual influencer experience;

Independent variable: parameters of virtual influencers—trust, reliability, relevance, expertise, the likelihood of purchase, and consideration of opinion;

Control variable: age, gender, and education.

H0:

The virtual influencer parameters do not impact people’s satisfaction level with virtual influencers’ experience.

H1:

The virtual influencer parameters impact people’s satisfaction level with virtual influencers’ experience.

The obtained results from the conducted tests (Table 13, Table 14 and Table 15) provide significant evidence to reject the null hypothesis. It can be inferred that virtual influencer parameters such as trust, reliability, relevance, and expertise have a considerable impact on consumer behaviour, leading to an increased preference for virtual influencers over human influencers. Moreover, these parameters significantly influence customer satisfaction levels following their interactions with virtual influencers. However, it should be noted that these findings are based solely on the perceptions of a small sample population, and, thus, generalization to a wider population should be performed with caution. Nevertheless, the observed trend of consumers exhibiting more trust in virtual influencers than human influencers calls for further investigation and research.

Table 13.

Model fitting (III).

Table 14.

Goodness of fit (III).

Table 15.

Pseudo R-square (III).

7. Conclusions

7.1. General Conclusions

This study investigated virtual influencers’ impact on customer behaviour, perceived trustworthiness, and preference over human influencers. The findings reveal that virtual influencers are preferred over human influencers, and factors such as trust, reliability, relevance, and expertise significantly contribute to their acceptance and preference. Moreover, these factors also influence customers’ opinions, considerations, and likelihood of purchase. The results of the descriptive statistics show that virtual influencers’ trust and expertise received the highest score, indicating that customers have faith in their opinions and believe in their expertise. All general research hypotheses but one (relevancy of opinion) were confirmed. This is to an extent contrary to the findings of Franke et al. (2023), whose study showed that consumers find it difficult to identify virtual influencers as such and that they still have more positive attitudes toward human endorsers in advertising campaigns.

The results of our study raise new questions: why do consumers trust a virtual influencer more when they assume that artificial intelligence runs the virtual influencer? This may lead to the assumption that a large number of consumers trust machines more than humans. This would be worrying. Although this study could not identify the underlying reasons for these findings, it can serve as a roadmap for future research in this field.

7.2. Contributions to Literature

This research demonstrates that virtual influencers are preferred over human influencers and are perceived as highly credible. This is likely due to the lack of biases in virtual influencer behaviour, as they are controlled by the brands they represent or by the assumption that virtual influencers are independent of human interference. The study also found that customers engage with virtual influencers at varying levels and can connect with them both intellectually and emotionally. These interactions positively impact purchase intentions and contribute to the consideration set of choices. The level of interaction and emotional connectedness with virtual influencers emphasises that users prioritise their relationship with influencers over their functionality. The study also suggests that virtual influencers directly impact purchase intention when the trust and credibility between consumers and influencers are established. Through parasocial interactions, customers can form solid social relationships with virtual influencers, contributing to the company’s brand value. The continuous engagement and interaction between virtual influencers and customers allow artificial intelligence engines to adapt quickly to customer preferences, increasing the credibility and trustworthiness of virtual influencers. The lack of time restrictions on virtual influencers’ availability for interaction further contributes to their engagement level with customers. Human influencers are found to be lagging behind virtual influencers in terms of customer response due to their inability to match the level of engagement and emotional connectedness that virtual influencers can provide. Additionally, the study raises the question of why consumers lose trust in human influencers, which opens the path to further research in behavioural sciences and influencer marketing.

7.3. Practical Contributions

The study has several practical contributions and managerial implications for brands and marketers.

Firstly, virtual influencers can replace human influencers adequately in marketing campaigns to increase customers’ purchase intention. Although creating credibility and trustworthiness for virtual influencers can initially be challenging, they can significantly enhance purchase intentions once established.

Secondly, virtual influencers are adaptable and flexible in defining characteristics, which is impossible with human influencers, leading to opportunities for identification and internalisation among target audiences.

Thirdly, virtual influencers can create more profound and long-lasting connections with customers, reducing brand endorsement costs in the long run and maintaining message continuity.

Finally, virtual influencers’ flexibility in programming and training artificial intelligence engines allows them to adapt to changing customer behaviours, which shortens time to market campaigns and enables companies to cater to the changing needs of their customers.

Virtual influencers, with higher credibility and trustworthiness than human influencers, are the future of influencer marketing and can increase purchase intention and overall brand awareness for companies. Therefore, companies must adapt to the changing marketing environment by utilising virtual influencers effectively.

7.4. Limitations

This study combines consumer perception and actions, making it challenging to generalise the behaviour and outcomes of the study without a sufficient sample size that represents all sectors and groups within society. Unfortunately, the sample size of 357 responses is limited and may over-represent a single group. The choice of self-selection (volunteer) sampling could have led to a biased sample as people tend not to respond to adverts, unless they have a strong interest/view to share or a motivation to take part and, therefore, are more likely to respond with demand characteristics. Additionally, the study was conducted in English, limiting the participants from non-English-speaking countries.

7.5. Future Research Roadmap

Future research should consider a global data-based study to gather perceptions from a large population not concentrated in a geographic location or sect. In addition, industry perspectives should be considered, and a set of influencer-specific studies should be conducted to see if the results can be generalised for all virtual influencers or only a few prominent and famous ones. Lastly, it would be helpful to analyse the impact of virtual influencer contributing factors, including interaction styles, humaneness, uncanniness, and overall look and feel. As mentioned above, the question of how human influencers can overcome the loss of trust might lead to further research.

Considering the above, it is likely that a generalisation of all the dimensions discussed in this research could be achieved.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of SBS Swiss Business School (2 September 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Due to privacy restrictions some data is not available. Other data can be requested from the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Alboqami, Hassan. 2023. Trust me, I’m an influencer!—Causal recipes for customer trust in artificial intelligence influencers in the retail industry. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 72: 103242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amelina, Dinna, and Yu-Qian Zhu. 2016. Investigating effectiveness of source credibility elements on social commerce endorsement: The case of Instagram in Indonesia. In PACIS 2016 Proceedings. pp. 232–41. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/pacis2016/232 (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Amos, Clinton, Gary Holmes, and David Strutton. 2008. Exploring the relationship between celebrity endorser effects and advertising effectiveness: A quantitative synthesis of effect size. International Journal of Advertising 27: 209–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenyan, Jbid, and Agata Mirowska. 2021. Almost Human? A Comparative Case Study on the Social Media Presence of Virtual Influencers. International Journal of Human Computer Studies 155: 102694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, Bamini K. P. D., Mohd Irwan Dahnil, and Wong Jiunn Yi. 2014. The impact of social media marketing medium toward purchase intention and brand loyalty among generation Y. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 148: 177–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, Elena, and Rob Lovegrove. 2021. Discordant Storytelling, ‘Honest Fakery’, Identity Peddling: How Uncanny CGI Characters Are Jamming Public Relations and Influencer Practices. Public Relations Inquiry 10: 265–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Duncan, and Nick Hayes. 2008. Influencer Marketing. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri, Arjun, and Morris B. Holbrook. 2001. The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of loyalty. Journal of Marketing 65: 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Siyoung, and Hichang Cho. 2017. Fostering parasocial relationships with celebrities on social media: Implications for celebrity endorsement. Psychology & Marketing 34: 481–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Brito Silva, Marianny Jessica, Lorena de Oliveira Ramos Delfino, Kaetana Alves Cerqueira, and Patrícia de Oliveira Campos. 2022. Avatar marketing: A study on the engagement and authenticity of virtual influencers on Instagram. Social Network Analysis and Mining 12: 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, Claudia, Andrea Groeppel-Klein, and Katrin Müller. 2023. Consumers’ responses to virtual influencers as advertising endorsers: Novel and effective or uncanny and deceiving? Journal of Advertising 52: 523–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlich, Michael. 2022. Micro-influencer marketing during the COVID-19 pandemic: New vistas or the end of an era? Journal of Digital & Social Media Marketing 9: 337–53. [Google Scholar]

- Gerlich, Michael. 2023. The Power of Personal Connections in Micro-Influencer Marketing: A Study on Consumer Behaviour and the Impact of Micro-Influencers. Transnational Marketing Journal 11: 131–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, Richard F. 1983. Classical and partial eta square in multifactor ANOVA designs. Educational and Psychological Measurement 43: 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henson, R. N. 2015. Analysis of variance (ANOVA). In Brain Mapping: An Encyclopedic Reference. Amsterdam: Elsevier, vol. 1, pp. 477–81. Available online: https://www.mrc-cbu.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/www/sites/3/2015/03/Henson_EN_15_ANOVA.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Hirschmann, Ralf. 2021. Virtual Influencers’ Impact on Purchasing Decisions Singapore 2020. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1103884/singapore-impact-of-virtual-influencerson-purchasing-decision/ (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Horton, Donald, and R. Richard Wohl. 1956. Mass communication and para-social interaction. Psychiatry: Journal for the Study of Interpersonal Processes 19: 215–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovland, Carl Iver, Irving Lester Janis, and Harold H. Kelley. 1953. Communication and Persuasion. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, Chin-Lung, Judy Chuan-Chuan Lin, and Hsiu-Sen Chiang. 2013. The effects of blogger recommendations on customers’ online shopping intentions. Internet Research 23: 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Castillo, David, and Raquel Sánchez-Fernández. 2019. The role of digital influencers in brand recommendation: Examining their impact on engagement, expected value and purchase intention. International Journal of Information Management 49: 366–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kádeková, Zdenka, and Maria Holienčinová. 2018. Influencer marketing as a modern phenomenon creating a new frontier of virtual opportunities. Communication Today 9: 90–105. [Google Scholar]

- Kapitan, Sommer, and David H. Silvera. 2016. From digital media influencers to celebrity endorsers: Attributions drive endorser effectiveness. Marketing Letters 27: 553–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Ferle, Carrie, and Sejung Marina Choi. 2005. The importance of perceived endorser credibility in South Korean advertising. Journal of Current Issue and Research in Advertising 27: 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarsfeld, Paul F., Bernard Berelson, and Hazel Gaudet. 1944. The People’s Choice. New York: Duell, Sloan & Pearce. [Google Scholar]

- Lewczyk, Maria. 2021. Why Brands Should Work with Virtual Influencers. Available online: https://www.virtualhumans.org/article/why-brands-should-work-with-virtual-influencers (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Liu, Xing, and Hari Koirala. 2012. Ordinal regression analysis: Using generalized ordinal logistic regression models to estimate educational data. Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods 11: 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Chen, and Shupei Yuan. 2019. Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. Journal of Interactive Advertising 19: 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, Anisa. 2021. Virtual(ly) Black Influencers Prove Racial Capital Is Virtual Too. Available online: https://medium.com/swlh/virtual-ly-black-influencers-proveracial-capital-is-virtual-too-7d94f484141a (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- McCormick, Karla. 2016. Celebrity endorsements: Influence of a product-endorser match on Millennials attitudes and purchase intentions. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 32: 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCracken, Grant. 1989. Who is the celebrity endorser? Cultural foundations of the endorsement process? Journal of Consumer Research 16: 310–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Fred, Irina V. Kozlenkova, Haizhong Wang, Tao Xie, and Robert W. Palmatier. 2021. An emerging theory of avatar marketing. Journal of Marketing 86: 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustakas, Evangelos, Nishtha Lamba, Dina Mahmoud, and C. Ranganathan. 2020. Blurring lines between fiction and reality: Perspectives of experts on marketing effectiveness of virtual influencers. Paper presented at International Conference on Cyber Security and Protection of Digital Services, Cyber Security, Dublin, Ireland, June 15–19; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, Kristine L., and Jesse Fox. 2018. Avatars and Computer Mediated Communication: A Review of the Definitions, Uses, and Effects of Digital Representations. Review of Communication Research 6: 30–53. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-55777-7 (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Oliveira, Antonio, and Paula Chimenti. 2021. Humanized Robots: A Proposition of Categories to Understand Virtual Influencers. Australasian Journal of Information Systems 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sands, Sean, Colin L. Campbell, Kirk Plangger, and Carla Ferraro. 2022. Unreal Influence: Leveraging AI in Influencer Marketing. European Journal of Marketing 56: 1721–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, Jan-Philipp, Priska Linda Breves, and Nora Anders. 2022. Parasocial interactions with real and virtual influencers: The role of perceived similarity and human-likeness. New Media & Society. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallarida, Ronald J., and Rodney B. Murray. 1987. Chi-square test. Manual of Pharmacologic Calculations: With Computer Programs, 140–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, Veronica L., and Kendra Fowler. 2020. Close encounters of the AI kind: Use of AI influencers as brand endorsers. Journal of Advertising 50: 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, Pedro, Mário Augusto, and Marta Matos. 2019. Antecedents and outcomes of digital influencer endorsement: An exploratory study. Psychol Mark 36: 1267–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivek, Shiri D., Sharon E. Beatty, and Robert M. Morgan. 2012. Customer engagement: Exploring customer relationships beyond purchase. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 20: 122–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Carrie. 2007. Research Methods. Journal of Business & Economics Research (JBER) 5: 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).