Translating Organizational Change into Entrepreneurial Identity—A Study of Energy Transition in a Large State-Owned Enterprise

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background of the Research

2.1. Energy Transition and Green Innovation

2.2. The Impact of External Change on Internal Identity

2.3. Green Innovation in State-Owned Enterprises

3. Materials and Methods

4. Analysis

4.1. Transformation and Change in the Organization

4.2. Innovating the Culture, Re-Inventing the Identity

“Maybe they (the operational areas) are the ones who see the rationale of making a change the least” … “theirs is an instant-by-instant business, with a very short view, because that’s the way it is […] none of them I think ever thought of saying: but in twenty years, are we still going to continue this kind of business in these terms?”(Interview with the top management 2020)

“no one says anymore: but why do we have to do this? who said that? It has become an established thing that we cannot not-react to and that we have to evolve”. … “we are used to evaluating what we do, but little the how”.(Employees interviews 2019)

“Everything was verticalized, it was easy to find the people in charge” [before] “the division of activities was well identified”. [After the changes] “we often found ourselves having to fix things by learning from mistakes”.(mid-managers interviews 2019)

“While there is a call for more resourcefulness, more entrepreneurship and innovativeness, there is a widespread perception among colleagues: paradoxically, we are verticalizing ourselves in decision-making processes.”(mid-managers interviews 2019)

“I see a bit of a difference in people who have had mobility and those who have not” … “it really helps young people who want to grow, but it puts a lot of pressure on middle management”.(Top management interviews 2020)

“No change is possible if the procedure is a cage as for evolution. One is locked in, literally, that is, if we have a system that punishes if you act contrary to procedure, it is obvious that no change will ever be made. And if it does come, it definitely comes in a completely dilated time frame compared to expectations”. … “The ‘Lean Simplify’ program has to go on the content, because if we keep writing the same things in fewer pages, we’re going to lengthen the lines on the page. I don’t think that’s what we’re at, I’m just saying that there are some things that are the ones that really lengthen the time for us: you have to look at whether you really have to do them all or maybe some of them can be deferred to later”.(Top management interviews 2020)

“There is a clear perception that each [initiative] taken individually is very important and very valuable; but then you risk fragmenting everyone’s efforts on too many things and this leads to a decrease in the benefit, in the perception of the benefit, by the end user […] in the end there is such a saturation that you launch the new initiative and one doesn’t even look at it anymore”.(mid-managers interviews 2019)

4.3. The Actions of Change

“I have always worked in this organization and I have to tell you that really, I have experienced a lot of changes. Even on my skin. But really extremely significant changes. In terms of business more significant than what we are experiencing today, there is no doubt about that, because this has been a company where logistics activities were a means, because the real business was buying, buying and selling gas, and it was transformed into a company where logistics activities were the end. The business with the gradual exit from the holding group. So, I experienced this change in the sense that in the year 2000, from scratch, we invented the job. That is, there was the blank sheet in 2000, and I assure you that this is a change”. One colleague shared the same view: “I am convinced, for goodness’ sake some experience behind me I have, that there is not a big difference between the changes we experienced 20 years ago and those we are experiencing now”.(Employees interviews 2019)

“An effort to make the old guard to see itself as the roots of the new, and to make people see how the new can only exist by maintaining what we have developed over so many years”.(Top management interviews 2020)

“This thing of giving things out has always bothered me a little bit” … “then we had to redo everything ourselves” … “I think the experience factor is coming a little bit to the back burner. You take it a little bit for granted, as if it’s easily acquired or replaced by a resource that maybe you take from the market and put it here”.(Employees interviews 2019)

“Those who are in the periphery, in the territory, and handle gas, know very well how dangerous gas is. At headquarters sometimes not”.(Employees interviews 2019)

“We are very good at managing contracts in (our country). We are able to manage the full cycle of a project, unpacking it, [… but] we are not structured for the private sector, we use the same procedures as the public sector, [… and] if we want to manage the private markets with the head of the public sector, forget it because we are to going anywhere” … “The company is not used to taking risks because our stock profile is a low-risk profile that rewards guaranteed profitability-it is a safe haven asset. You have to be careful about changing the risk profile because you risk losing investors along the way. It is a trade-off that is not easy to manage. It’s not that we are not able to take the risks: we deliberately don’t take the risks”.(Top management interviews 2020)

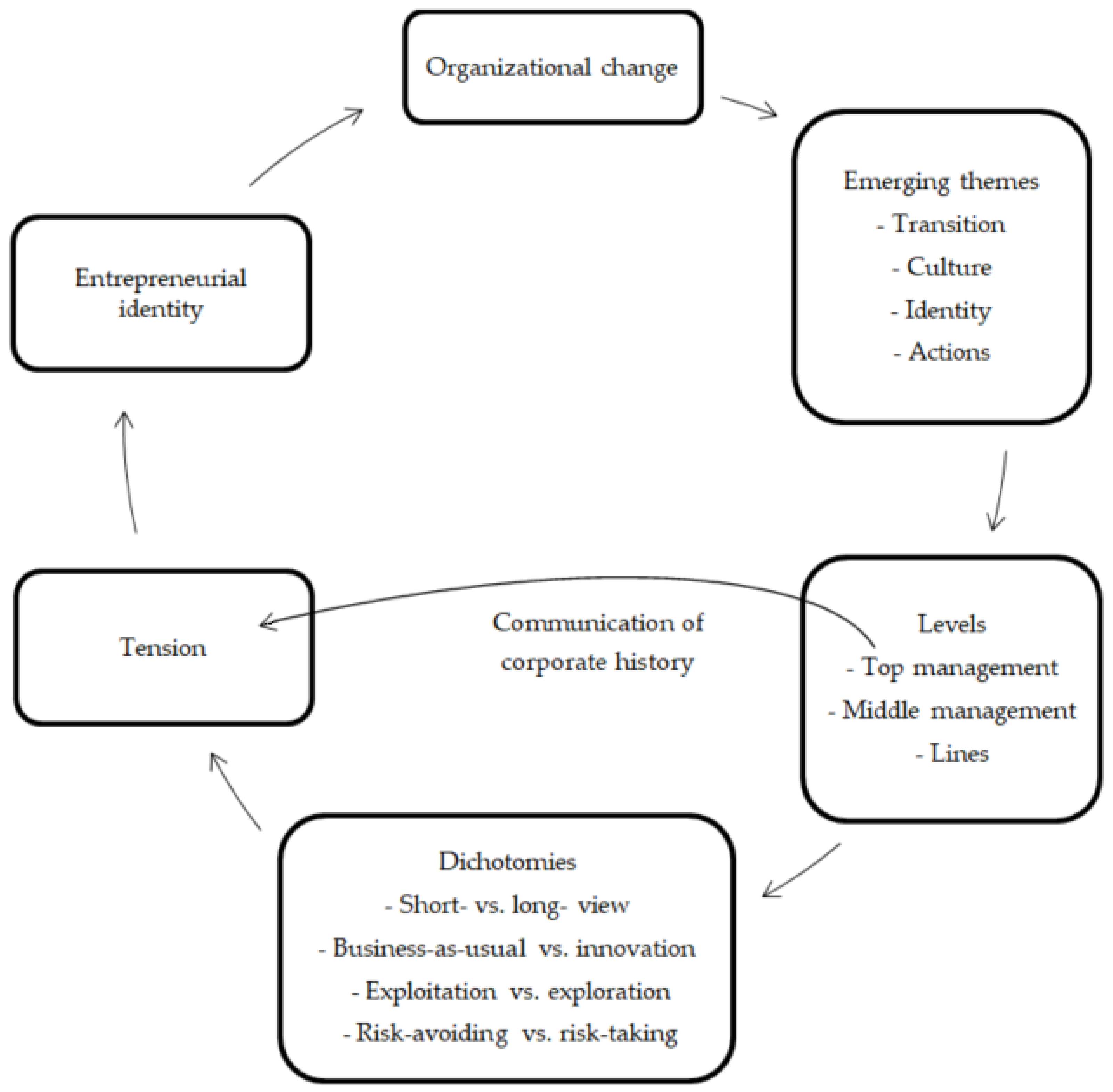

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Albert, Stuart, and David Whetten. 1985. Organizational identity. Research in Organizational Behavior 7: 263–95. [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich, Howard. 1999. Organizations Evolving. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Alolabi, Yousef Ahmad, Kartinah Ayupp, and Muneer Al Dwaikat. 2011. Issues and Implications of Readiness to Change. Administrative Sciences 11: 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvesson, Mats. 2003. Beyond neopositivists, romantics, and localists: A reflexive approach to interviews in organizational research. Academy of Management Review 28: 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amason, Allen C., and Ann C. Mooney. 2008. The Icarus paradox revisited: How strong performance sows the seeds of dysfunction in future strategic decision-making. Strategic Organization 6: 407–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apergis, Nicholas, and James E. Payne. 2011. On the causal dynamics between renewable and non-renewable energy consumption and economic growth in developed and developing countries. Energy Systems 2: 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argote, Linda. 2012. Organizational Learning: Creating, Retaining and Transferring Knowledge. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth, Blake E., Scott A. Johnson, Michael A. Hogg, and Deborah J. Terry. 2001. Which hat to wear. In Social Identity Processes in Organizational Contexts. Abingdon: Taylor and Francis, pp. 32–48. ISBN 9781317762836. [Google Scholar]

- Augenstein, Karoline, and Alexandra Palzkill. 2016. The Dilemma of Incumbents in Sustainability Transitions: A Narrative Approach. Administrative Sciences 6: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awwad, Abdulkareem, Abdel Latef M. Anouze, and Nelson Oly Ndubisi. 2022. Green Customer and Supplier Integration for Competitive Advantage: The Mediation Effect of Sustainable Product Innovation. Sustainability 14: 10153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Han, Tangwei Teng, Xianzhong Cao, Shengpeng Wang, and Senlin Hu. 2022. The Threshold Effect of Knowledge Diversity on Urban Green Innovation Efficiency Using the Yangtze River Delta Region as an Example. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 10600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, Markus C., ed. 2008. Handbook of Organizational Routines. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bordoff, Jason, and L. Meghan O’Sullivan. 2022. Green Upheaval. Foreign Affairs. June 8. Available online: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/world/2021-11-30/geopolitics-energy-green-upheaval (accessed on 22 June 2023).

- Bortolotti, Bernardo, Veljko Fotak, and Brian Wolfe. 2019. Innovation and State Owned Enterprises. BAFFI CAREFIN Centre Research Paper No. 2018-72. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3150280 (accessed on 22 June 2023).

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2013. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2019. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 11: 589–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, Victoria Clarke, and Nicola Rance. 2014. How to use thematic analysis with interview data. In The Counselling & Psychotherapy Research Handbook. Edited by Andreas Vossler and Naomi Moller. London: Sage, pp. 183–97. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Andrew D., and Michael A. Lewis. 2011. Identities, discipline and routines. Organization Studies 32: 871–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellacci, Fulvio, and Christine Mee Lie. 2017. A taxonomy of green innovators: Empirical evidence from South Korea. Journal of Cleaner Production 143: 1036–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelo, Manuel, Catarina Delgado, Sónia Ferreira Gomes, and Teresa Cristina Pereira Eugénio. 2014. Factors influencing the assurance of sustainability reports in the context of the economic crisis in Portugal. Managerial Auditing Journal 29: 237–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Jinyong, Xiaochi Wang, Wan Shen, Yanyan Tan, Liviu Marian Matac, and Sarminah Samad. 2022. Environmental Uncertainty, Environmental Regulation and Enterprises’ Green Technological Innovation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 9781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Yu-Shan, Ching-Hsun Chang, and Yu-Hsien Lin. 2014. The Determinants of Green Radical and Incremental Innovation Performance: Green Shared Vision, Green Absorptive Capacity, and Green Organizational Ambidexterity. Sustainability 6: 7787–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Shuping, Lingjie Meng, and Weizhong Wang. 2022. The Impact of Environmental Regulation on Green Energy Technology Innovation—Evidence from China. Sustainability 14: 8501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corley, Kevin G., and Dennis A. Gioia. 2004. Identity ambiguity and change in the wake of a corporate spin-off. Administrative Science Quarterly 49: 173–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, John W. 2014. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Czarniawska, Barbara, and Guje Sevon, eds. 2005. Global Ideas. How Ideas, Objects and Practices Travel in the Global Economy. Copenhagen: Liber. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Zhao, Haodong Xu, Zhifeng Zhang, Yipin Lyu, Yuqi Lu, and Hongyan Duan. 2022. Whether Green Finance Improves Green Innovation of Listed Companies—Evidence from China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 10882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorfleitner, Gregor, Gerhard Halbritter, and Mai Nguyen. 2015. Measuring the level and risk of corporate responsibility—An empirical comparison of different esg rating approaches. Journal of Asset Management 16: 450–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, Juliet, and Robert Nash. 2017. Private benefits of public control: Evidence of political and economic benefits of state ownership. Journal of Corporate Finance 46: 232–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Yueping, and Huanhuan Wang. 2022. Green Innovation Sustainability: How Green Market Orientation and Absorptive Capacity Matter? Sustainability 14: 8192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, Robert G., Ioannis Ioannou, and George Serafeim. 2014. The impact of corporate sustainability on organizational processes and performance. Management Science 60: 2835–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Nick, and Sierk Ybema. 2010. Marketing identities: Shifting circles of identification in interorganizational relationships. Organization Studies 31: 279–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez, Rodrigo A., Valeria Espinoza, Roberto D. Ponce Oliva, Felipe Vásquez-Lavín, and Stefan Gelcich. 2021. Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis for Renewable Energies: Research Trends, Gaps and the Challenge of Improving Participation. Sustainability 13: 3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, Martha S. 2000. Organizational routines as a source of continuous change. Organization Science 11: 611–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, Martha S., and Anat Rafaeli. 2002. Organizational routines as sources of connections and understandings. Journal of Management Studies 9: 309–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, Martha S., and Brian T. Pentland. 2003. Reconceptualizing organizational routines as a source of flexibility and change. Administrative Science Quarterly 48: 94–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, Greg, Suresh Kotha, and Amrita Lahiri. 2016. Changing with the times: An integrated view of identity, legitimacy, and new venture life cycles. Academy of Management Review 41: 383–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Shanshan, Wenqi Li, Jiayi Meng, Jianfeng Shi, and Jianhua Zhu. 2023. A Study on the Impact Mechanism of Digitalization on Corporate Green Innovation. Sustainability 15: 6407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, William, and Andrew Brown. 2009. Working with Qualitative Data. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, Dennis A. 1998. From Individual to Organizational Identity. In Identity in Organizations: Building Theory through Conversations. Edited by D. A. Whetten and P. C. Godfrey. Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp. 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, Jessica, Jennifer Hadden, Thomas Hale, and Paasha Mahdavi. 2021. Transition, hedge, or resist? Understanding political and economic behavior toward decarbonization in the oil and gas industry. Review of International Political Economy 2021: 1946708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinot, Jacob, Zina Barghouti, and Ricardo Chiva. 2022. Understanding Green Innovation: A Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 14: 5787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Anil K., Ken G. Smith, and Christina E. Shalley. 2006. The interplay between exploration and exploitation. Academy of Management Journal 49: 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, Julia, Andrew Inkpen, and Kannan Ramaswamy. 2022. The oil and gas industry: Finding the right stance in the energy transition sweepstakes. Journal of Business Strategy 43: 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Jiangtao, Ruyin Zheng, Hepu Deng, and Yinglei Zhou. 2019. Green supply chain collaborative innovation, absorptive capacity and innovation performance: Evidence from China. Journal of Cleaner Production 241: 118377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Hui, Youbin Zhu, Jian Wang, and Minglang Zhang. 2022. Will green financial policy help improve China’s environmental quality? the role of digital finance and green technology innovation. Environ. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 30: 10527–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Po-Hsuan, Hao Liang, and Pedro Matos. 2021. Leviathan Inc. And Corporate Environmental Engagement. Darden Business School Working Paper No. 2960832, ECGI—Finance Working Paper No. 526/2017. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2960832 (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- Imasiku, Katundu, Valerie Thomas, and Etienne Ntagwirumugara. 2019. Unraveling Green Information Technology Systems as a Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Game-Changer. Administrative Sciences 9: 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. 2021. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Edited by Masson-Delmotte Valérie, Panmao Zhai, Anna Pirani, Sarah L. Connors, Clotilde Péan, Sophie Berger, Nada Caud, Yang Chen, Leah Goldfarb, Melissa I. Gomis and et al. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe, Amy Myers, Zdenka Myslikova, Qi Qi, Fang Zhang, Soyoung Oh, and Jareer Elass. 2022. Green innovation of state-owned oil and gas enterprises in BRICS countries: A review of performance. Climate Policy 18: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Gareth R. 2013. Organizational Theory, Design, and Change. New York: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Landoni, Matteo. 2020. Knowledge creation in state-owned enterprises. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 53: 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Laurie. 2019. Organizational change. In Origins and Traditions of Organizational Communication. Edited by A. M. Nicoter. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 406–23. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Dayuan, Yini Zhao, Lu Zhang, Xiaohong Chen, and Cuicui Cao. 2018. Impact of quality management on green innovation. Journal Cleaning Production 170: 462–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Bin, and Lin Li. 2022. Urban green innovation efficiency and its influential factors: The Chinese evidence. Environment, Development and Sustainability 20: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, Dic, Ling Gao, and Yuchen Lin. 2022. State ownership and innovations: Lessons from the mixed-ownership reforms of China’s listed companies. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 60: 302–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Yusen, Muhammad Salman, and Zhengnan Lu. 2021. Heterogeneous impacts of environmental regulations and foreign direct investment on green innovation across different regions in China. Science of the Total Environment 759: 143744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüscher, Lotte S., and Marianne W. Lewis. 2008. Organizational change and managerial sensemaking: Working through paradox. Academy of Management Journal 51: 221–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Xiang, Young-Seok Ock, Fengpei Wu, and Zhenyang Zhang. 2022. The Effect of Internal Control on Green Innovation: Corporate Environmental Investment as a Mediator. Sustainability 14: 1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcel, Valérie. 2019. National oil companies of the future. Annales Des Mines—Responsabilité et Environnement 95: 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, James G. 1991. Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization Science 2: 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maris, Georgios, and Floros Flouros. 2021. The Green Deal, National Energy and Climate Plans in Europe: Member States’ Compliance and Strategies. Administrative Sciences 11: 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markard, Jochen, Bernhard Truffer, and Dieter M. Imboden. 2004. The impacts of market liberalization on innovation processes in the electricity sector. Energy & Environment 15: 201–14. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, G. S., M. A. Dias, and J. N. Vianna. 2020. Innovation in the electricity sector in the age of disruptive technologies and renewable energy sources: A bibliometric study from 1991 to 2019. International Journal of Advanced Engineering Research and Science (IJAERS) 7: 261–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matkovskaya, Yana S., Elena Vechkinzova, Yelena Petrenko, and Larissa Steblyakova. 2021. Problems of innovative development of oil companies: Actual state, forecast and directions for overcoming the prolonged innovation pause. Energies 14: 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Danny. 1992. The Icarus paradox: How exceptional companies bring about their own downfall. Business Horizons 35: 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladenova, Irena. 2022. Relation between Organizational Capacity for Change and Readiness for Change. Administrative Sciences 12: 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugenyi, Andrew Ronnie, Charles Karemera, Joshua Wesana, and Michaël Dooms. 2022. Institutionalization of Organizational Change Outcomes in Development Cooperation Projects: The Mediating Role of Internal Stakeholder Change-Related Beliefs. Administrative Sciences 12: 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasim, Saboohi, and Sushil. 2011. Revisiting Organizational Change: Exploring the Paradox of Managing Continuity and Change. Journal of Change Management 11: 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolini, Davide. 2010. Medical innovation as a process of translation: A case from the field of telemedicine. British Journal of Management 21: 1011–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2018. Ownership and Governance of State-Owned Enterprises: A Compendium of National Practices. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/corporate/ownership-and-governance-of-state-owned-enterprises-a-compendium-of-national-practices.htm (accessed on 19 March 2023).

- OECD. 2020. OECD Business and Finance Outlook 2020:2020: Sustainable and Resilient Finance, 6. State-Owned Enterprises, Sustainable Finance and Resilience. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmigiani, Anne, and Jennifer Howard-Grenville. 2011. Routines revisited: Exploring the capabilities and practice perspectives. Academy of Management Annals 5: 413–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PwC. 2015. State-Owned Enterprises—Catalysts for Public Value Creation? Available online: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/psrc/publications/assets/pwc-state-owned-enterprise-psrc.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Raisch, Sebastian, and Julian Birkinshaw. 2008. Organizational ambidexterity: Antecedents, outcomes, and moderators. Journal of Management 34: 375–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, Roberto Leonardo, Mariarosaria Lombardi, Pasquale Giungato, and Caterina Tricase. 2020. Trends in Scientific Literature on Energy Return Ratio of Renewable Energy Sources for Supporting Policymakers. Administrative Sciences 10: 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rerup, Claus, and Martha S. Feldman. 2011. Routines as a source of change in organizational schemata: The role of trial-and-error learning. Academy of Management Journal 54: 577–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, Dariusz, Iryna Bashynska, Olena Pavlova, Kostiantyn Pavlov, Nelia Chorna, and Roman Chornyi. 2023. Investment and Innovation Activity of Renewable Energy Sources in the Electric Power Industry in the South-Eastern Region of Ukraine. Energies 16: 2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, Jörgen. 2005. How do we justify knowledge produced within interpretive approaches? Organizational Research Methods 8: 41–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, Jorgen, and Axel Targama. 2007. Managing Understanding in Organizations. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Sellitto, Miguel Afonso, Clarissa Gracioli Camfield, and Shqipe Buzuku. 2020. Green innovation and competitive advantages in a furniture industrial cluster: A survey and structural model. Sustainable Production and Consumption 23: 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shani, A. B., Susan Albers Mohrman, William A. Pasmore, Bengt Stymne, and Niclas Adler, eds. 2007. Handbook of Collaborative Management Research. New York: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Wendy K., and Marianne W. Lewis. 2011. Toward a theory of paradox: A dynamic equilibrium model of organizing. Academy of Management Review 36: 381–403. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Yongbo, and Hui Sun. 2021. Green Innovation Strategy and Ambidextrous Green Innovation: The Mediating Effects of Green Supply Chain Integration. Sustainability 13: 4876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takalo, Salim Karimi, Hossein Sayyadi Tooranloo, and Zahra Shahabaldini Parizi. 2021. Green innovation: A systematic literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production 279: 122474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, Gareth, Nikki Hayfield, Virginia Braun, and Victoria Clarke. 2017. “Thematic analysis”. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2nd ed. Edited by C. Willig and W. S. Rogers. London: SAGE, pp. 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Tonurist, Piret, and Erkki Karo. 2016. State owned enterprises as instruments of innovation policy. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics 87: 623–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Yu, and Weiku Wu. 2021. How does green innovation improve enterprises’ competitive advantage? The role of organizational learning. Sustainable Production and Consumption 26: 504–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Ping, Hua Bu, and Fengqin Liu. 2022a. Internal Control and Enterprise Green Innovation. Energies 15: 2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yanyu, Qinghua You, and Yuanbo Qiao. 2022b. Political genes drive innovation: Political endorsements and low-quality innovation. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 60: 407–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, Klaus, and Mary Ann Glynn. 2006. Making sense with institutions: Context, thought and action in Karl Weick’s theory. Organization Studies 27: 1639–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, Karl E. 1995. Sensemaking in Organizations. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Sa, and Zejun Li. 2021. The Impact of Innovation Activities, Foreign Direct Investment on Improved Green Productivity: Evidence From Developing Countries. Frontiers in Environmental Science 9: 635261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, Salman, Adnan Khan, Maryam Farooq, and Muhammad Irfan. 2022. Integrating green business strategies and green competencies to enhance green innovation: Evidence from manufacturing firms of Pakistan. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 29: 39500–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Ji Yeon, and Taewoo Roh. 2019. Open for Green Innovation: From the Perspective of Green Process and Green Consumer Innovation. Sustainability 11: 3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Yuxue, Xiang Su, and Shuangliang Yao. 2022. Can green finance promote green innovation? The moderating effect of environmental regulation. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 29: 74540–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Jijian, Guang Yang, Xuhui Ding, and Jie Qin. 2022. Can green bonds empower green technology innovation of enterprises? Environmental Science and Pollution Research 9: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Guangyou, Jieyu Zhu, and Sumei Luo. 2022. The impact of fintech innovation on green growth in China: Mediating effect of green finance. Ecological Economics 193: 107308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Theme | Transition |

|---|---|

| Lines | Reaction and evolution |

| Middle managers | Learning process |

| Top managers | Perspective |

| Dichotomy | Short- vs. long-view |

| Theme | Culture |

|---|---|

| Lines | Hierarchical |

| Middle managers | Process-oriented |

| Top managers | Entrepreneurial |

| Dichotomy | Business-as-usual vs. innovation |

| Theme | Identity |

|---|---|

| Lines | Expertise |

| Middle managers | Fragmentation |

| Top managers | Evolution |

| Dichotomy | Exploitation vs. exploration |

| Theme | Actions |

|---|---|

| Lines | Discipline-oriented |

| Middle managers | Success-oriented |

| Top managers | Opportunity-oriented |

| Dichotomy | Risk-avoiding vs. risk-taking |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Landoni, M. Translating Organizational Change into Entrepreneurial Identity—A Study of Energy Transition in a Large State-Owned Enterprise. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13070160

Landoni M. Translating Organizational Change into Entrepreneurial Identity—A Study of Energy Transition in a Large State-Owned Enterprise. Administrative Sciences. 2023; 13(7):160. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13070160

Chicago/Turabian StyleLandoni, Matteo. 2023. "Translating Organizational Change into Entrepreneurial Identity—A Study of Energy Transition in a Large State-Owned Enterprise" Administrative Sciences 13, no. 7: 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13070160

APA StyleLandoni, M. (2023). Translating Organizational Change into Entrepreneurial Identity—A Study of Energy Transition in a Large State-Owned Enterprise. Administrative Sciences, 13(7), 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13070160