Abstract

The aim of this article is to investigate two external flexible forms of employment—the leasing of workers through Temporary Work Agencies (TWAs) and the contracted workers employed through Business Service Providers (contractors). Undoubtedly, these two forms of employment are complex and often give rise to confusion. First, this article reviews the characteristics of these types of workers and the operation of these businesses. Second, it presents the results of a mixed method of empirical research (quantitative and qualitative) regarding contracted workers. Our sample was 365 contracted workers from the cities of Athens, Thessaloniki and Patras, Greece. In particular, quantitative research is conducted using a methodology called RDS (Respondent Driven Sampling) that is innovative in the field of labour economics and labour relations. Some significant findings of our qualitative research are used to improve, extend, and interpret the quantitative results. Our research proves that contracted workers, who are employed at the premises of the banks, are leased workers, and the contracting undertakings usually operate unlawfully as TWAs. Our research proves that Banks in Greece are using “pseudo-contracting” to circumvent the European Directive 2008/104/EC and the Greek Laws 4052/2012 and 4254/2014, both of which provide institutional protection to workers leased through TWAs. In more detail, the relevant European Directive and the Greek Law 4052/2012 provide salary equality and equal labour rights for the leased workers in Greece and the EU, when they share the same qualifications as the permanent employees of the user undertakings. The employers’ aim in adopting this policy is mainly to pay lower salaries to contracted workers, who in practice have the characteristics of leased workers.

1. Introduction

Non-standard forms of employment, also called “flexible” or “new forms” of employment, such as temporary employment, part-time employment, seasonal employment, project agreement, leasing through TWAs, and outsourcing are a worldwide rapidly expanding phenomenon that affects more than one-third of the worldwide workforce (ILO 2022b; Thomson and Hünefeld 2021; OECD 2019). Flexible or new forms of employment emerged in the 1980s and gained popularity during the acute financial crisis (2007), as well as during the recent pandemic COVID-19 that also hugely affected Europe and the USA. More specifically, in 2022, the EU-27 marked rates of 12.1% of temporary employment and 17.6% of part-time employment over total employment (Eurostat 2023).

Enterprises turn to flexible forms of employment when aiming to reduce labour costs and to increase their productivity and competitiveness (Forde and Slater 2005; Pavlopoulos 2015; Rompoti et al. 2022). More specifically, enterprises reduce their internally allocated range of tasks and assign part of or entire activities to external undertakings, thus expanding labour market segmentation and amplifying social inequalities among the employees (Forde and Slater 2005; Grimshaw et al. 2001). Such external undertakings are the Temporary Work Agencies and the Business Service Providers, which are both analysed in this article.

This article investigates two external flexible forms of employment, how they work, and the correlation between them. The first flexible form of employment is temporary employment through Temporary Work Agencies (hereinafter the “TWAs”), also known as “leasing” of workers through TWAs. The leasing of workers through TWAs consists of the temporary leasing of people to a second user-undertaking to cover special needs.

The second flexible form of employment consists in workers “contracted” through Business Service Providers (hereinafter the “contractors”) who undertake to complete projects or provide services through outsourcing. This article primarily aims to investigate a special category of flexible “contracted” workers whose place of work is not at the premises of the contractor undertaking but at the facilities of the user-undertaking who outsources the project (i.e., in-house outsourced workers).

“Outsourcing” is a business strategy according to which enterprises externally assign a service or a project to Business Service Providers (contractors). Enterprises resort to outsourcing agreements either with the aim to reduce their labour costs or to obtain higher flexibility and access to innovation and technology (Galanaki 2005; Kartaltzis 2004). The practice of workers providing their services at the premises of the enterprise is called “in-house outsourcing”, whereas when they provide their work at the premises of the contractor, this is called “out-house outsourcing”. According to our research, external assignment of projects as well as their completion at the premises of the assigning undertaking (i.e., in-house outsourcing) developed markedly in Greece during the periods of the financial crisis and the pandemic.

The basic research questions investigated in this paper are:

First, what are the basic characteristics and what is the institutional framework for the protection of workers leased through TWAs in Europe? What are the numbers of leased workers in Europe? (See the theoretical framework, Section 2).

Second, according to the literature, what are the top reasons for which employers-undertakings address to external businesses (such as TWAs and Business Service Providers)? How do Business Service Providers usually operate in Greece? (See the theoretical framework, Section 2).

Third, what is primarily the profile and what are the labour characteristics of contracted workers in the Banking sector, providing their services at the Banks’ premises (i.e., in-house outsourced workers)? Does this type of worker receive a lower salary and enjoy less labour rights compared to permanent employees in Greece? (See the theoretical framework and the results of the empirical primary research in the Banking sector, Section 2 and Section 4, respectively).

Fourth, do contracted workers employed as in-house outsourced staff in reality conceal the practice of leasing workers? If yes, what are the reasons for which this occurs in Greece? (See the theoretical framework and the results of the empirical primary research in the Banking sector, Section 2 and Section 4, respectively).

Fifth, according to the literature, what are the criteria to distinguish leasing through TWAs from pseudo-contracting1 that is arranged between undertakings and Business Service Providers? (See the theoretical framework and the results of the empirical primary research in the Banking sector, Section 2 and Section 4, respectively).

There are strong indications that this type of contracted workers (i.e., in-house outsourced) are, in reality, leased workers. In practice, this form of employment is a way to bypass the legislation regarding leased workers, pay lower wages, and curtail their rights and benefits compared to permanent employees.

These indications led us to set our main research assumptions.

First, that contracted workers employed at the premises of a user undertaking are actually leased workers, with the sole difference of being paid lower remunerations and having less labour rights compared to the permanent personnel of the user undertaking. Moreover, the contracted workers are employed for years at the under undertaking, covering constant and ongoing needs. Second, contracting companies usually operate illegally as TWAs.

This paper makes a significant contribution both on a theoretical and an empirical level. More specifically, we contribute to the literature by investigating the practice of leasing workers through TWAs and the main features of this practice. On an empirical level our contribution consists in the reference to quantitative indexes regarding the size of the category of leased workers in the EU member states. Another special category mentioned is the contracted workers through Business Service Providers (contracting undertakings). Such workers are placed at the premises of the undertakings that have assigned the project (in-house outsourced workers) and not at the premises of the contractors (out-house outsourced workers). More specifically, there is a common confusion around the difference between contracted workers employed for “in-house outsourcing” and those workers leased through TWAs. Our research in the Greek Banking sector points to the possibility that in-house outsourced workers are actually leased workers and that contracting companies usually operate unlawfully as TWAs. However, there are no available data from Eurostat on in-house outsourced workers, which would allow us to determine the actual size of such workers. In addition, literature references to contracted workers employed for “in-house outsourcing”, but actually covering up “leased” workers is extremely limited. In Greece, the relevant literature only contains the legal-institutional aspect (Zerdelis 2017; Leventis 2017) and our study is actually the first attempt internationally to conduct empirical research on the issue. More specifically, we studied the contracted workers providing their services at the premises of banks in Greece (i.e., in-house outsourced workers). It is worth noting that the difficulty to identify this population (i.e., in-house outsourced workers) led us to employ a methodology that is new in our field of work. This methodology is the Respondent Driven Sampling (RDS), used for the first time in the field of labour economics and labour relations. Finally, our primary research in the Banking Sector proves that contracted workers, who are employed at the premises of the banks are actually leased workers and the contracting undertakings often operate unlawfully as TWAs. Our research proves that the contracting companies and the Banks in Greece are using “pseudo-contracting” to circumvent the European Directive 2008/104/EC and the Greek Laws 4052/2012 and 4254/2014, both of which provide institutional protection to the workers leased through TWAs.

The structure of the article is as follows. The second section contains a review of the literature on the phenomenon of leasing workers, an overview of the motives of the employers and the operation of the businesses, as well as of the features-indications for the distinction between pseudo-contracting and the actual practice of leasing workers. Our aim is to showcase the main characteristics of these flexible forms of employment in order to acquire deep comprehension and make the distinction. This can lead to workers in Europe avoiding the practice of “pseudo-contracting” in the future and being deceived by employers. The third part contains an analysis of the methodology employed to conduct the investigation. In addition, it analyses the challenges faced in order to identify the contracted workers (i.e., in-house outsourced workers). The fourth section presents the results of the empirical research in the Banking Sector in Greece. The profile of contracted workers is described, regarding their demographics and labour characteristics. The presentation of the criteria-characteristics of “pseudo-contracting” will help us prove, for the first time, that contracted workers actually cover up leased personnel, and that contracting and user enterprises usually conclude fictitious or pseudo contracts. The fifth section presents the conclusions and suggestions for further research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Leased and “Pseudo-Contracted” Workers in Greece and the EU

The leasing of workers through TWAs made its first appearance in the USA in the 1940s, in western European countries in the 1960s, and in the rest of the European countries during and after the 1990s (Voss et al. 2013; Papadimitriou 2007). An enterprise that leases personnel is called a “Temporary Work Agency” (TWA) or “Temporary Agency” or “Agency Work” or “Agency Employment” (ILO 2009, 2013). In Europe, the leasing of workers through TWAs is one of the most developing forms of employment (Hakansson and Isidorsson 2012; ILO 2009, 2013). In 2022, leased workers amounted to 2.6% of the total employed population in the EU-27 (Eurostat 2023).

The European Directive 2008/104/EC, after 30 years of tough negotiations, provides protection for those employed through TWAs in the EU. In Greece, the “leasing” of workers was officially recognized and delineated initially with Law 2956/2001 and later on with Law 4052/2012, which also incorporated the European Directive 2008/104/EC (2008). Thus, it is seen that the establishment of a framework for the protection of workers leased through TWAs was greatly delayed both on a Greek and an EU level (For details regarding Greece see Section 2.2 Labor Laws in Greece). Pursuant to the Private Employment Agencies Convention (ILO, Convention 181 on 19.6.97), the legal structure and operation of the Temporary Work Agencies, both in Europe and internationally, is established through a triangular relation (TWA-leased worker–user undertaking) (ILO 2009, 2022a).

The term “leasing” of personnel through TWAs means the temporary work, which is provided by the leased worker to a second user undertaking. In particular, the leased employee enters into a contract or dependent work relationship, full- or part-time, for a fixed or indefinite period with the TWA (direct employer)2, to provide their services not to the TWA itself, but temporarily3 to the user undertaking (indirect employer)4. The remunerations of leased workers, during their temporary placement with the indirect employer, are, as the law provides, those that would apply if the employees were hired for the same job position and with the same qualifications by the user undertaking, in accordance with the European Directive 2008/104/EC (European Directive 2008/104/EC 2008; Greek Laws 4052/2012 and 2956/2001) (For details regarding Greece see Section 2.2 Labor Laws in Greece). Therefore, the remunerations cannot be lower than the specified sector-level or professional or business-level Collective Agreements, which apply to the permanent employees of the indirect employer. It is worth noting that in the UK and Ireland, leased workers may also be under a “sui generis” agreement, meaning that apart from a contract with a TWA they may also be working as freelancers (Agrapidas 2006, 2013).

Although the EU has established a robust institutional framework for the protection of leased workers on the basis of the European Directive 2008/104/EC, this form of employment is correctly considered as one of the most vulnerable forms of work due to the segmentation of the labour market and the co-existence of two employers, i.e., the TWA and the user-undertaking (Fudge 2011; Doerflinger and Pulignano 2015). More specifically, although flexible forms of employment represent a large amount of manpower, they are considered to be among the most precarious. Temporary employment, leasing through TWAs, contracted workers, and non-standard forms of employment mainly include low level occupations, deprived of professional advancement, with low salaries and benefits, lack of education and training, and higher labour insecurity that gives rise to labour dissatisfaction and negative consequences on the worker’s mental and physical health (Ferreira and Gomes 2022; Thomson and Hünefeld 2021; Mitlacher 2008).

As mentioned above, the leasing of workers through TWAs is one of the most developing forms of employment and the relevant employment rates vary across Europe. In 2022, leased workers amounted to 2.6% of the total employed population in the EU-27 (Eurostat 2023). The countries with the highest rates of leased workers in 2022 were the Netherlands (5.2%), Spain (3.9%), Ireland (3.7%), Germany (3.3%), and Sweden (2.8%). At the other end of the scale, the countries with the lowest rates of leased workers were Belgium (1.9%), Portugal (1.4%), Italy (1.0%), Denmark, and Greece (0.6%) (Eurostat 2023). In Greece, there is reasonable suspicion that the numbers of leased workers are actually higher. A possible reason is that contracted workers employed at the premises of the user undertaking (i.e., in-house outsourced workers) are possibly workers who are actually leased. Consequently, if this is true, it is undoubtable that the number of leased workers is higher (Rompoti and Ioannides 2019, 2023).

According to the above, our basic research assumption is that a portion of the contracted workers through in-house outsourcing are actually leased employees and that they are remunerated less than the permanent personnel. More specifically, strong indications lead us to believe that the employers hire these contracted workers in order to circumvent the European Directive 2008/104/EC and the Greek laws. In particular, the European Directive and the Greek Laws provide equality between the leased workers through TWAs and the permanent employees for the period that the leased workers are assigned to the user undertaking. Thus, contracting companies often operate unlawfully as TWAs by concealing the leased personnel. We believe that it is possible that “virtual/pseudo contracting” is also the case in other EU countries, however there are no relevant empirical studies available (For details regarding Greece see Section 2.2 Labor Laws in Greece).

According to the literature, the main reason for which employer undertakings decide to lease workers through TWAs is to cover their short-term and emergency needs (Eichhorst et al. 2013; Autor 2008; Forde and Slater 2005). In addition, a significant incentive is the reduction of the labour cost, since this form of employment allows the user undertakings to avoid assuming any employer obligations and liabilities (e.g., hiring processes, salaries, withholding of contributions, etc.). In this way, the user-undertakings are not burdened with costly potential dismissals, which would apply had they been the direct employers (Eichhorst et al. 2013; Autor 2008). Another main reason for opting for this form of employment is the immediate and reliable spotting of flexible human resources, equipped with the appropriate qualifications, skills, and specialties, who provide expertise, new knowledge and innovative ideas to the user undertakings. Moreover, the latter may employ “knowledge economy” workers (Forde and Slater 2005). These are employees in high-expertise posts of the tertiary sector (provision of services, such as technical, administrative, and managerial professions, IT professions, etc.). Finally, the user-undertakings have the opportunity to assess the work quality and the skills of the workers leased before hiring them permanently to their businesses so as to avoid any financial or other risk in the future (Autor and Houseman 2010; Forde and Slater 2005).

The main incentives for enterprises to adopt the practice of outsourcing and use contracted workers are to reduce the labour costs, enhance flexibility and make use of more specialized human resources, who carry expertise and innovative ideas in their field (Costa 2001; Galanaki 2005). When outsourcing takes place within a group of companies, it is called “internal outsourcing”, while when used to external businesses, it is either “in-house outsourcing” or “out-house outsourcing”. “In-house outsourcing” means that in order to complete a task, the contracted workers must work at the premises of the project-assigning business (user undertaking), while “out-house outsourcing” means that the contracted workers complete the project at the facilities of the contractor. Outsourcing, especially “in-house outsourcing”, should not be confused with the leasing through TWAs, because although the two concepts share some common traits, they are actually very different. The basic difference between a worker leased through a TWA and a contracted worker is the temporary employment or leasing of the leased worker to a second undertaking (user business). On the contrary, the task of a contracted worker, either out-house outsourced or in-house outsourced, is to complete and deliver a project to the entity that has assigned it.

However, apart from the advantages for the businesses, literature only contains a few disadvantages of this practice. More specifically, there are indications that Businesses Service Providers (contractors) and users conclude “virtual or pseudo” project agreements (Zerdelis 2017; Leventis 2017; Rompoti and Ioannides 2019, 2023). Undoubtedly, such agreements benefit the user undertakings, providing higher flexibility and reduction of the labour costs. Especially in Greece, it is most probable that some employers aim to avoid the restrictions applicable for the case of leased workers, as set by Laws 4052/2012 and 4254/2014, as well as to avoid equal pay and other rights both for the leased and the permanent workers, as stipulated by Laws 4052/2012 and 4093/2012, which incorporate the European Directive 2008/104/EC into the national legislation (European Directive 2008/104/EC 2008; Law 4052/2012 2012; Law 4254/2014 2014; Law 4093/2012 2012) (For details regarding Greece see Section 2.2 Labor Laws in Greece). It should be noted that the salaries, insurance rights, and the rest of the working conditions of the contracted workers who either work at the facilities of the user undertaking (in-house outsourcing) or at places other than the user’s premises (out-house outsourcing) are set mainly in Greece in accordance with the National General Collective Labour Agreement (NGCLA). Therefore, the salaries are not determined by the sector-level or same-profession or business-level collective labour agreements that apply to the permanent employees of the user undertakings. Therefore, contracted workers do not have the right to salaries equal to those of the permanent employees of the user undertaking, whereas, as already mentioned, workers leased through TWAs do benefit from this right. Therefore, the contracted workers receive lower remuneration and benefits compared to the permanent employees of the user undertaking. (Details about Greece can be found in Section 2.2 Labour Laws in Greece). It is our opinion that this leads to dissatisfied contracted workers on an employment level, as they are deprived of the opportunity to pay equality and professional advancement in the user undertaking. On top of that, they feel great insecurity regarding their future in the job.

Τhe robust institutional framework of the European Directive 2008/104/EC on leased workers is bypassed through the emergence and development of other forms of employment, such as in-house outsourcing or the conclusion of “virtual or pseudo projects” between Business Service Providers and user undertakings (Rompoti and Ioannides 2019; Zerdelis 2017; Leventis 2017). Workers contracted through Business Service Providers and placed at the user undertaking to complete a project (in-house outsourced workers) are called in our research “pseudo-contracted” workers, as they have traits of leased workers through TWAs. More specifically, our research showed that contracting businesses in Greece usually undertake fake or “virtual” projects or pseudo-contracts and operate unlawfully as TWAs, thus concealing what is actually the leasing of workers (See details about Greece in Section 2.2 Labour Laws in Greece).

It is also worth noting that many groups of companies (usually multinational) operate a subsidiary Temporary Agency Work and operate a subsidiary Business Service Provider (contractor). This raises red flags, as it is a strong indication that contracting businesses often operate as TWAs and lease personnel.

It is evident that a “grey zone” is created between leasing personnel through TWAs and “pseudo” contracting that covers up illegally leased personnel, when the workers are employed at the premises of the user undertaking (Rompoti and Ioannides 2019, 2023; Zerdelis 2017; Leventis 2017).

In Greece, neither the legislators nor the jurisprudence have dealt in depth with the issue of pseudo-contracting, as has been the case in Germany. The German law on personnel leasing through TWAs was amended on “1 April 2017” incorporating provisions in order to fight illegal leasing of workers through virtual project agreements. More specifically, the German law imposes to TWAs and the user undertakings to explicitly identify their agreements as “personnel allocation agreements”, otherwise they are considered void, and the leasing of workers is illegal.

The main criterion for distinguishing the phenomenon of leased personnel through TWAs from “contracted” personnel is the exercise of the managerial right (e.g., instructions about the place, working time, etc.), stipulated by the European Directive 2008/104/EC, which sets the provisions on temporary work through TWAs. In particular, the managerial right over the employee contracted through a contracting enterprise is exercised by the contractor who bears the responsibility of the project, while in the case of employees leased through TWAs, it is the user undertaking who exercises this right (indirect employer).

In the absence of legislative provisions on illegal leasing of workers in many EU countries, the jurisprudence (courts) has set a list of criteria-characteristics to make the distinction between leasing of workers through TWAs and the “virtual” contracting that covers up leased workers.

According to the relevant literature (Greiner 2014; European Directive 2008/104/EC 2008; Ulber 2013; Schuren 2007; Ulrici 2017; Hamann 1995; Sansone 2011; Zerdelis 2017; Leventis 2017; Law 4052/2012 2012, etc.), the list of criteria-indications set by the jurisprudence, as well as the labour law incorporated into our questionnaire of primary research, are:

First, the use of employees by the user undertaking exercising the managerial right. Consequently, when the user undertaking exercises the managerial right, this is an indication of personnel leasing agreement through TWAs. Second, the use of equipment and materials of the user undertaking (e.g., computers, telephones, chairs, etc.). This criterion is indicative of personnel leasing agreement through TWAs. Third, the integration in or cooperation with the permanent staff of the user undertaking. This criterion is another indication of personnel leasing agreement through TWAs. Fourth, the way of determining the remuneration or remuneration per hour (e.g., remuneration per working hour). This criterion is indicative of personnel leasing agreement through TWAs. Fifth, the contract sets the number of employees as well as their required qualifications (e.g., knowledge, certificates of study, etc.). This is a criterion of personnel leasing agreement through TWAs. Sixth, the working hours are the same or almost the same as those of the permanent employees. Undoubtedly, this is indicative of personnel leasing agreement through TWAs. Seventh, the project agreement between the user undertaking and the contracting business mentions a general description of the project (e.g., secretarial or administrative support), and more clarifications are provided to the employees by the user undertaking. This criterion is an indication of “pseudo-contracting” agreement. As widely known, the phenomenon of leasing employees means that the user undertakings define what tasks the employees should fulfil. Eighth, when the duration of the project and the type of duties of the workers in the user undertaking concern constant and ongoing duties. Particularly, these duties were previously performed by the permanent personnel. These are indicative of a “pseudo-contracting” agreement as the project should have an expiry date and cover needs of a temporary nature. Ninth, the assignment and execution by the contracted staff of tasks that are irrelevant to the project they have been asked to complete. This is another indication of the “pseudo-contracting” agreement, as the user undertaking assigns to the workers other tasks or additional tasks than those originally described in their contract. Tenth, the Business Service Providers (contractors) do not have the appropriate organization, logistical infrastructure, or know-how to provide their services to many different sectors and different enterprises. This criterion is indicative of a “pseudo-contracting” agreement, since contracting businesses illegally operate as TWAs that simply lease personnel. Eleventh, in the event of any problem arising during the project, the workers are accountable to the user undertaking. This is indicative of a “pseudo-contracting” agreement, as the contracted workers are accountable to the contractors. Particularly, the responsibility regarding the deficiencies and defects of the project during its course or when it is completed is legally borne by the contracting enterprise.

The above criteria-indications were utilized in our primary empirical research by incorporating them in the questionnaire that served as our basic tool. To our knowledge, it is the first time on an international level that a distinction has been attempted between leasing workers through TWAs and “pseudo-contracting”, as there are no other empirical studies on this issue (see Appendix A).

It is worth noting that the literature also includes a part of authors who question some of the above criteria-indications about the distinction between a genuine project agreement and the leasing of workers through TWAs (Baeck and Winzer 2015; Rieble and Vielmeier 2011; Hamann 1995).

Their arguments are mainly as follows: First, as far as the equipment that the contracting workers are using to complete their tasks, it is not necessarily provided by the contracting company, but it could be also become available through the user undertaking. Thus, the use of the equipment of the user undertaking does not mean that the role and character of the project agreement is altered and that a practice of covering up leased personnel is employed. Secondly, the permanent personnel of the user undertaking may well give instructions and supervise the contracted workers, without it raising doubts about the role of the project agreement. Third, the close collaboration between the contracted workers and the permanent staff of the user undertaking aiming to carry out a project does not necessarily conceal a practice of leasing workers. On the contrary, it could actually be a factual project agreement and the collaboration between contracted and permanent workers is a prerequisite for a successful outcome. Fourth, it is possible that the project agreement only lays out a general description of the project and that further instructions are provided at a later stage by the user undertaking; this should not question the role of the project agreement. Fifth, many project agreements set the remuneration based on the hours required for the completion of the project. This way of payment does not alter the nature of the project agreement and should not automatically lead to the assumption that this is a case of concealed leasing of workers.

2.2. Labor Laws in Greece

The institution of leasing workers through TWAs was officially recognized in Greece in 2001 with Law 2956/2001. Many EU member states had already recognized it many years ago (Papadimitriou 2007; Voss et al. 2013). The delay of recognition and legalization of this practice in Greece was due to the actions of Greek unions that argued that this form of employment should have been prohibited from the start (Zerdelis 2017; Stratoulis 2005). However, the embracing of this practice by employers and the fact that the lack of a legal framework was leading to the encroachment of the workers’ labour rights, led the national legislators, with the accordance of the unions, to recognize this practice in order to provide statutory protection of the leased workers. In more details, the conceptual and institutional content of the “leasing” of workers was initially delineated in Greece in 2001 with Law 2956/2001 (2001) (articles 20–26) and in 2003 with Law 3144/2003 (2003), as well as with subsequent amendments in 2010, 2012, and 2014 pursuant to the respective laws: Law 3846/2010 (2010), Law 3899/2010 (2010) and Law 4052/2012 (2012) (Articles 113–133), Law 4093/2012 (2012) and Law 4254/2014 (2014). Law 4052/2012 (2012), amended pursuant to Law 4093/2012 (2012) and Law 4254/2014 (2014), incorporate in the Greek legislation the regulations of the European Directive 2008/104/EC (2008) on the rights of workers “leased” though TWAs.

Law 4052/2012 (2012) specifically concerns the provision of a minimal legal protection regarding the “equation” of pays and of the basic labour and insurance rights between “leased” and permanent workers employed at the user undertaking for the same job position and with similar qualifications.

In addition, Law 4052/2012 (2012) and Law 4254/2014 (2014) contain stricter provisions on trade union rights and on the hygiene and safety of the leased workers, as well as stricter conditions regarding hiring and dismissing such workers.

Moreover, Law 4052/2012 (2012) provides that the length of assignment of a leased worker to the user undertaking cannot exceed a period of 36 months in Greece. In the event that this period is exceeded, the worker reserves the right to conclude an indefinite term employment contract with the user undertaking (Law 4052/2012 2012, article 117).

Moreover, Law 4093/2012 (2012) provides that 23 days must elapse for the renewal of the contract between the leased worker and the TWA; in the event that the worker continues working at the user undertaking after the expiry of their temporary placement with the user undertaking (max 36 months). In the event that the time-frame of 23 days has not elapsed, the worker reserves the right to conclude an indefinite term employment contract with the user undertaking (Law 4093/2012 2012, article 1).

To be noted that the maximum length of temporary placement of the leased workers with the user undertaking is set in the EU by each member-state individually and not pursuant to the European Directive 2008/104/EC (2008). However, the existence of different maximum periods set by the national states may turn void the efforts made with the provisions of the European Directive 2008/104/EC (2008) aiming to the protection of leased workers and of temporary employment offered through TWAs (Zerdelis 2017; European Directive 2008/104/EC 2008; Rompoti and Ioannides 2019, 2023).

Especially in Greece, it is noted that currently employers are attempting to circumvent the laws protecting leased workers through TWAs and they do so by reducing the demand of services through TWAs and increasing the demand though Business Service Providers or contracting businesses. This shift is due to the fact that employers now consider leasing workers to be an expensive form of employment, since the Greek legislation has incorporated European Directive 2008/104/EC (2008) that provides pay equality and equal work conditions and rights for leased and permanent staff, for the entire period that the leased workers provide their services at the premises of the user undertaking. Thus, employers try to circumvent the European Directive and they seem to have turned from the practice of leasing workers through TWAs to assigning services or projects to contracting businesses. The contracted workers then complete the project or service assigned either at the premises of the contractor (οut-house outsourced workers) or at the location of the user undertaking (in-house outsourced workers). Note that contracted workers in Greece do not receive the same remunerations and do not benefit from the same insurance rights as the permanent employees of the user undertaking that assigns the project. Pay inequality is not justified by a difference of educational background between the two categories of workers. Many times the contracted workers are more qualified than the permanent staff. Lower salaries and less rights mainly stem from the fact that contracted workers mainly sign in Greece the National General Collective Work agreement (lower thresholds of pays and less rights that use as a safety net for the entirety of workers), whereas the permanent staff sign the Sector-Level Collective Agreement (higher pays and more rights based on the sector of employment). Therefore, the existence of contracted workers circumvents, in our opinion, the legislative framework of the European Directive. There is no specific European Directive or legislation to protect contracted workers, as is the case for workers leased through TWAs, and they are only covered by the laws and the collective agreements that concern the overall working population.

The use of contracted workers at the premises of the user undertaking (in-house outsourced workers) for the fulfilment of a project often creates a grey zone between actual contracting, leasing of personnel through TWAs and virtual or pseudo-contracting, the latter concealing, in our opinion, the workers that have been unlawfully leased. In more details, when contracting companies in Greece place workers at the premises of the user undertaking for the completion of a project (in-house outsourced workers), they usually operate “unlawfully” as TWAs, covering up the “pseudo” or allegedly “contracted” workers, who are actually leased personnel. These workers are characterized as “pseudo-contracted” staff on the grounds that they share the same traits as the workers leased through TWAs. As already mentioned, the main feature of the Temporary Work Agencies is the temporary leasing of workers to the user undertakings (Rompoti and Ioannides 2019, 2023). This practice is what we call “pseudo-contracted workers”, since they mainly have the traits of leased workers and not of contracted ones. Therefore, the contracting companies do not mainly operate as businesses offering outsourcing services, but rather as TWAs.

Undoubtedly, the fact that permanent staff, workers leased through TWAs and contracted workers all work at the same location, renders even more difficult the distinction among them. As already stated, the main criterion to distinguish a leasing agreement from a contracting agreement is the exercise of the managerial right, also recognized by EU’s labour law.

More specifically, the contractor exercises the managerial right in the cases of contracted workers, and he is responsible for the completion of the project. On the other side, the managerial right over workers leased through TWAs is exercised by the user undertaking (indirect employer). Nevertheless, it is noted that, in practice, it is the user undertaking that exercises the managerial right over contracted workers, a fact that indicates that contracted workers show traits of leased workers (see Section 4.2 Results of the empirical research). There are, of course, several other main criteria-indications to distinguish the two forms of contracts, and they are used both in Greece and other EU member-states due to the lack of a specific legislation on the protection of contracted workers (See Literature review Section 2.1 and Section 2.2 and Section 4.2 Results of the empirical research).

The above analysis underlines the need for a common European policy on labour relations through the enactment of EU directives and their incorporation in the national legislation of each member-state, though allowing part of the decision and policy making to the member-states.

The aim is to develop an institutionally robust European Social Model (ESM) that will promote social discourse, collective agreements and negotiation, pay equality for all workers, the European social policy, and social justice (Rompoti et al. 2022; Rompoti and Feronas 2017; Jakab 2022).

3. Materials and Methods

Discussion of the Difficulties in Identifying Contracted Workers: The Quantitative Research and the Development of Respondent Driven Sampling (RDS) Methodology

After identifying the target population of the research, namely the contracted employees (i.e., workers employed through in-house outsourcing), we had to outline our sampling strategy. Unfortunately, Eurostat provides no quantitative data on contracted workers employed at the premises of a user undertaking (i.e., in-house outsourced workers), thus we had to conduct our own primary research.

First, it would not be feasible to conduct this research at the premises of the business service providers (contractors), meaning the employers of these contracted workers. The reason is that in Greece there is no record of contracting businesses at the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, or at the Work Inspection services, so the number and identity of these contracting business remains largely unknown. Moreover, it is worth noting that the ILO makes no reference to the Business Service Providers (contractors), regarding their number or their exact details. On the contrary, the ILO refers to Private Temporary Employment Agencies that include the Temporary Work Agencies (TWAs) and the Private Work Agencies (IGEE in Greek). Therefore, accessing these workers through the Business Service Providers (contractors) was not an option. But even if the number and details of the contractors were known, it is likely that we would not be allowed to access their list of employees in order to obtain our sampling frame. It is a flexible form of employment on the “edge” of legality, and it would be hard to persuade the employers (contractors) to share such information with us.

As a second alternative we have sent emails to major Greek Banks that routinely use contracted workers (i.e., employees through in-house outsourcing), asking them to grant us access to these employees. These attempts proved fruitless as we received no reply regarding permission to access their premises. This was not to our surprise, since the user undertakings often make efforts to conceal the fact that they lease employees or assign services or projects to third companies. Their aim is to safeguard their corporate reputation and protect their “brand name” and profits. Therefore, it was more than certain that banks would be negative to offer any facilitation for this research. It is evident that it became impossible to access their premises or even the directories of the contracting companies and banks in order to conduct a random sampling survey regarding the contracted workers.

Based on the above, random sampling was ruled out, and we had to turn to an alternative methodology. Therefore, we relied on the Respondent Driven Sampling (RDS) method. RDS is widely used as a more effective method to find hidden or difficult to trace populations, linked through social networks. The RDS methodology is similar to snowball sampling. Both methods are used for hard-to-reach populations. However, the main difference is that RDS uses an appropriate mathematical processing for random sampling, thus ensuring that the sample is representative. Snowball sampling5 is a method in which the sample is collected due to the absence of a list for random sampling, and the sample is not representative of the population studied (non-probability sampling method).

Our research was conducted using the explanatory sequential mixed methods design, which combines quantitative and qualitative research. In the explanatory sequential mixed methods design, the qualitative research (open-ended survey questions) comes after the quantitative research (closed-ended survey questions). In more detail, the results of the qualitative research improve, extend, or interpret the initial quantitative results (see Creswell 2016; Morse and Niehaus 2009; Tashakkori and Teddlie 2011; Green 2007). This article mainly focuses on the results of the quantitative research. Wherever deemed appropriate, results of the qualitative research are also presented in order to extend or interpret our initial quantitative results.

The research on the “pseudo-contracted” workers was carried out from January to December 2019 (12 months) on a nationwide level. The questionnaire created contains many original questions (e.g., pseudo-contracting related questions), which make it largely original. Our sample was 365 contracted workers from the cities of Athens, Thessaloniki and Patras, Greece. Our sample included 272 women and 93 men.

As already mentioned above, the quantitative research was based on the Respondent Driven Sampling (RDS) methodology. Since 2011, more than 600 articles have been published using the RDS methodology (Leon et al. 2016). The RDS method is used when the number of the population being studied is not recorded or when it is too difficult for the researcher to access books or records, or complete lists of people constituting the given population, or to public services, in order to conduct a random sample survey. Therefore, it is used as a method to obtain representative samples for hidden or hard-to-reach populations, where researchers cannot use standard sampling methods (Leon et al. 2016; Magnani et al. 2005; Heckathorn 1997). RDS has been used in the fields of health, arts, and culture. The first study in which the RDS methodology was developed was by Heckathorn in 1997, in his attempt to identify needle drug users in several US States. RDS has been similarly used in conjunction with hard-to-reach populations such as immigrants, homeless, sex workers, jazz artists–musicians, patients with chronic diseases, and others.

Our survey for the collection of primary data was completed when we reached a total of 365 contracted employees of the Banking Sector from Athens, Thessaloniki and Patras, Greece. If we had carried out simple random sampling, then for a confidence interval of 95% and for an estimated population, according to the unions of these workers, of approximately 4000 people, the necessary minimum sample would have to be around 180 persons. According to Salganik (2006), in order not only unbiased but also efficient, RDS estimators should (usually, but not always) rely on a larger sample, which would result from multiplying the design effect by the sample size of simple random sampling. Although the design effect can even be below one, in most cases it is usually around 2. That is why we collected a sample of 365 persons.

Unfortunately, the fact that the category of contracted workers has not been studied before on an empirical level limits our discussion and comparison of our results with previous research. To the best of our knowledge, it is the first time on an international level that the RDS methodology has been employed with regard to contracted workers, exercising their duties at the premises of a user undertaking (i.e., in-house outsourced workers). Also, for the first time, the RDS methodology is applied in the fields of labour economics and labour relations.

According to the literature, there are three main steps to take in order to implement this methodology correctly. These steps have been followed in our research on pseudo-contracted workers in the banking sector (see Leon et al. 2016; Johnston et al. 2016; Gile et al. 2015; Heckathorn 2002; Heckathorn et al. 2001; Tyldum and Johnston 2014).

The first step is the seed selection. Research using the RDS methodology starts with a small number of seeds (3–15 individuals). The seeds must be different individuals and well networked in the field in question. However, the seeds do not have to be randomly selected. In our research with pseudo-contracted workers, the initial seeds were thirteen (13).

The second step includes the process of interviewing and recruiting people. Seeds are interviewed and are then given a predetermined number of coupons to recruit other people. These people belong to the same category as them (e.g., same profession) and are probably interested in participating in this research (Wave 1). Therefore, the RDS methodology is applied to people linked to each other (social network-colleagues). Following that, wave 1 recruits are interviewed and, in their turn, they recruit other interested parties (wave 2). In their turn, wave 2 recruits complete the interview and recruit other interested individuals (wave 3) and so on, until the required sample is achieved. In our research, 19 waves were created.

From the beginning of the research, researchers must scrutinize in detail the individuals as to who recruited whom. The basic idea behind the RDS methodology is that the seeds produce several random “sprouts” (i.e., new members in the sample). In particular, the sample should be large enough to maintain long referral chains (new sprouts) without repeating sample participants.

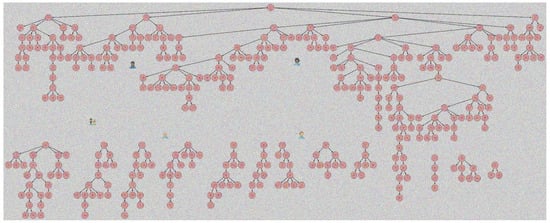

As a third step, researchers must ask the survey participants about the number of people of the hidden population that they know and interact with daily (e.g., workers in the same occupation). With this question, the researchers aim to learn the number of their social contacts–colleagues (social network). The figure related to this methodology is presented below (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The Methodology, RDS.

The interview process was conducted based on the principles of respect, ethics, and confidentiality towards the workers. In particular, in order to keep the identities of the participants confidential, questionnaires were coded and did not include their full names. Also, the employees themselves determined the day, time, and place that suited them best for the interview (usually close to their workplace). This practice, as well as sharing the results of the research with the participants, shows respect. It has to be said that this primary research has been a time-consuming and laborious process. Proper planning played an important role for the completion of the survey.

The results of the statistical analysis (quantitative research) that are presented in the next chapter were estimated with the help of the “RDS Analyst” statistical package, which is the appropriate software for processing data collected via the RDS method (Gile et al. 2015; Handcock et al. 2013). The values of variables presented below serve as estimators for the entire population, as they were derived using the RDS methodology. The results are supplemented, where necessary, with the relevant provisions of the labour law, as well as with the results of the qualitative research on the same sample of workers, according to the explanatory sequential mixed methods design.

More specifically, regarding the qualitative research, in-person interviews were conducted using open semi-structured questions. Semi-structured questions are useful in that they do not limit opinions–stances–perceptions of the respondents (Creswell 2016; Tsiolis 2014). The interviews for the qualitative research were initially conducted with the Chairperson of the union of contracted workers of the Association of Leased Personnel in the Banking Sector (SYDAPTT) in the years 2018–2019 (approximately 33 interviews). Interviews were conducted in Athens, at the union’s offices, and lasted approximately 40 min each time.

As far as the interviews with the contracted workers of the Banking sector are concerned (365 interviews, same as the sample of workers), they were conducted in 2019 using the explanatory sequential mixed methods design (quantitative and qualitative research). The interviews were conducted in person in Athens, Thessaloniki and Patras, were the respondents work. First, the workers answered the quantitative research questionnaire (closed questions) and the qualitative research questionnaire (open questions) followed, using the explanatory mixed methods design. Therefore, as far as the integration of quantitative and qualitative data on the workers are concerned, the quantitative research results were drawn first and were followed by those of the qualitative research. Consequently, our qualitative research about the workers in our study worked supplementarily to quantitative research in order to allow a better interpretation or the expansions of the results, where necessary. The total duration of each interview was 606 min. The duration for the closed questions (quantitative research) was 30–35 min and for the open questions (qualitative research) the duration was 25–30 min.

In the qualitative research, both in the interviews with the Chairman and the workers, the main tool was a recorder for the accurate recording of the discussions upon acquiring the respondents’ consent. Another significant tool was the notes we were taking during the interviews with respondents that did not consent to the recording of their interview. The processing of primary data from the qualitative research with the Chairman and the workers followed the stages described below.

First, preparation and organization of the primary data for analysis. Second, investigation and coding of the data. Third, coding for the creation of units per topic. Fourth, reference and interpretation of the qualitative findings. Fifth, validation of the accuracy of the findings (Creswell 2016). Data processing in the qualitative research was performed by the researchers and not using any software. The reasons for this approach were: First, the analysis contained a small database (e.g., less than 500 pages of transcriptions or field notes) and second, the researchers wished to remain close to the data, in direct contact with them and without the interference of a software. As Morison and Moir (1998) note, the researcher fully maintains the right to carry out research without using any computer software.

On the other hand, the statistical analysis in the quantitative research was conducted using the RDS Analyst software package.

This paper mainly focuses on the quantitative research due to the topic of the questionnaire studied.

4. Results of Empirical Field Research

4.1. Demographic, Work Characteristics, and Educational Level of Contracted Workers

This section describes the demographic and work characteristics of contracted workers who provide their services at the facilities of the banks (see Appendix A). Specifically, 365 workers constitute the sample in our research. In particular, these employees live permanently and work in the following cities: In Athens there was 86.7% (317), in Thessaloniki there was 7.8% (31), and in Patras there was 5.5% (17) of the sample. We chose the three largest cities of Greece, where businesses and more specifically banks assign part of or entire projects to external Business providers (i.e., outsourcing). Therefore, the largest part of these workers is concentrated in Athens, since it is the city where many and large contractors and client-undertakings operate.

We initially present the demographic and labour characteristics of the population under investigation, according to our research. As mentioned before, the numbers that will be presented below are estimators of the corresponding parameters of the population of the examined workers (and not of the sample) and derived with the help of the methodology used and the relevant statistical programme.

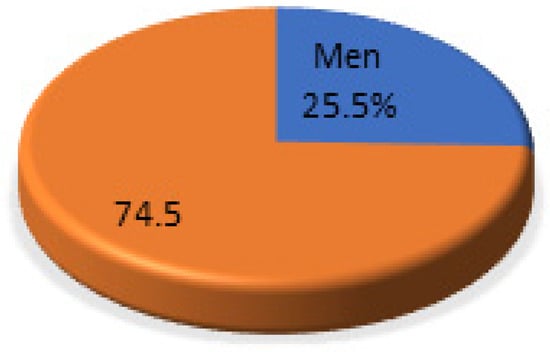

According to the data, the highest percentage of contracted workers in the banking sector are women, representing 74.5% (272) of the total (95% c.i.7: 67.0–81.8%) and only 25.5% (93) of the population are men (95% c.i.: 18.1–32.9%). See Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Percentages by gender of contracted workers in the Banking Sector, 2019. Source: Data from primary empirical research, microdata processed by the researchers.

The ages of contracted workers range from 23–59 years and their average age is 38 years old (Table 1).

Table 1.

Ages of contracted workers in deciles.

Regarding their marital status, the largest part of the population is single, 59.0% (95% c.i.: 52.0–66.1%), 30.4% are married (95% c.i.: 24.1–36.4%), and 10.6% of the population are divorced (95% c.i.: 6.6–14.5%). The mean value of the total number of members of the family/household of the population is 2.7 people and workers with children have an average of 1.7 children (Table 2).

Table 2.

Marital status of contracted workers.

Regarding their educational background, the highest rate of the population, 66.4%, are graduates of higher education/university, and 7.7% of them hold a master’s degree. However, 65.7% of this population is employed in a sector different than that of their studies (95% c.i. 58.7–72.7%). Overall, 20.0% of the population are high secondary school graduates, and 13.6% of the population are graduates of Vocational Educational Institutes/O.A.E.D. [Hellenic Manpower Organization] Schools. Those with higher education have an average duration of studies of 15.0 years (of which 9 years is obligatory). See Table 3.

Table 3.

Level of education of contracted workers.

It is worth noting that according to the interviews of the qualitative research with the workers, the fact that many times the contracted workers have a stronger educational background than permanent employees in the banking sector is again confirmed. However, they are paid less and are deprived of any career advancement compared to the permanent employees of the banking sector (qualitative research, part of the explanatory mixed methods design). For more details, see Section 4.2 Results of the quantitative research (paragraph on salaries, qualitative research, part of the explanatory mixed methods design). Moreover, the interview with the Chairman (qualitative research) confirms the pay inequality between the two categories of workers.

Regarding the nationality of contracted workers, our entire population (100% and the entire sample as well) consisted of Greek people. During the time that our research was conducted, the Banking sector in Greece was employing contracted workers only of Greek nationality, and this was also confirmed by the Chairman of the Association of Leased Personnel in the Banking sector during our interview with her (qualitative research).

The first significant finding of our research, mentioned in priority at this point, is that people in this form of employment do not see positively working through contractors, at an overwhelming rate of 98.8% (95% c.i.: 97.7–100%), and see this as positive only at the rate of 1.2% (Table 4).

Table 4.

Do you want to work in a contacting business?

With regard to the contract signed by the examined category of workers with the contracting enterprises, 76.2% of the population (95% c.i.: 65.7–86.7%) are under an indefinite term contract and 23.8% (95% c.i.: 13.2–34.2%) have a fixed-term contract (Table 5).

Table 5.

Type of contract of contracted workers.

The entire population (100% and the entire sample as well) states that the employment contract they have signed with the contracting enterprise constitutes their main work. Their average length of employment is 10 years (mean: 122 months) for both full-time and part-time indefinite term contract workers and almost 4 years (mean: 46.6 months) for employees with fixed-term contracts, both full-time and part-time. The high percentage of contracted workers with indefinite term contracts is a strong indication, if not a proof, that these workers have been employed for years by the Banks, i.e., the user undertakings, covering established and permanent needs, and that these people are trapped in the phenomenon of “pseudo-contracting” (dead trap). At the same time, the constant renewal of fixed-term contracts for workers with this status leads these workers to feel more insecure, without giving them the possibility to enter an indefinite term contract.

4.2. Criteria for the Distinction of Leasing and “Pseudo” Contract Agreement and Wage Differences

In this section, an analysis is made of the eleven questions that were asked to the contracted employees of the Banking Sector (i.e., in-house outsourced workers), which were based on the eleven criteria–characteristics for the distinction of leasing through TWAs and pseudo project agreement through Business Service Providers (see Appendix A). The questions, as mentioned above, were derived from the relevant literature, the labour law, the legislation, as well as from the jurisprudence of countries that have no legislation to distinguish the leasing agreement (through a TWAS) from a project agreement (through Business Service Providers) (Greiner 2014; Ulber 2013; European Directive 2008/104/EC 2008; Law 4052/2012 2012; Zerdelis 2017; Leventis 2017).

The answers to these questions, according to our research, prove that the contracting businesses are performing pseudo-contracting, that they are operating “unlawfully” as TWAs, and that they are actually concealing leased workers.

According to the first criterion-question, about whether the managerial and supervisory right (e.g., instructions, orders, control of the project or service) is exercised by the user undertaking, our entire population of the contracted employees of the Banking Sector (100% and evidently the entire sample as well) state that the managerial right is exercised by the user undertakings (Banks) and not by the contracting businesses.

The EU legislation, via the European Directive and the Greek legislation, Law 4052/2012, which refer to temporary employment or leasing of personnel through TWAs, provide that the managerial right is exercised by the user undertaking (indirect employer) and not by the TWA (direct employer). This fact is an important proof that the contracting enterprises operate in reality as TWAs and that the banks conceal leased workers. It is worth noting that the exercise of the managerial right is considered as the fundamental and most important criterion for distinguishing the project contract from the assignment or lease contract of personnel.

Regarding the second criterion-question on whether the contracted workers use the equipment and the logistical infrastructure (e.g., computers, telephones, chairs, etc.) of the user undertaking to which they are assigned for the completion of the project or service, our entire population (100%) of the contracted staff in the banking sector claim that they use the equipment of the user undertaking. The fact that the equipment is provided by the company that assigns the project (the Bank) and not by the contracting enterprise, which is responsible for this project, is an additional proof of “pseudo-contracting”, which in practice conceals leased personnel.

Regarding the third criterion-question, about whether the contracted workers work together and in the same work groups with the permanent staff of the user undertaking (e.g., as with the supervisors or permanent workers) 99.9% answered positively (95% c.i.: 99.7–100%) and only 0.1% answered negatively. The fact that an employee works together with the permanent staff of the user undertaking is an additional proof of leased staff.

Regarding the fourth criterion-question, about whether the exclusive and dominant element for calculating the remuneration of contracted workers is their hours of work (duration) and not the ultimate completion of the project, our entire population (100%) of contracted workers in the banking sector answer positively. Particularly, they answer that the exclusive and dominant basis for the calculation of their remuneration is the hours of work (duration) and not the final completion of the project. Hourly pay is a proof that workers are leased.

Regarding the fifth criterion-question, about the project contract between the employer and the contractor, and on whether the user undertaking determines the number of workers to be employed in the project as well as the qualifications they must have, 57.5% answered that they do not know (95% c.i.: 50.6–64.4%) and 42.5% answer positively (95% c.i: 35.5–49.4%). This criterion-characteristic is an additional proof of “pseudo contracting”, which in practice conceals leased personnel.

According to the testimonies of the employees (taken during the qualitative research), it appears that the user undertakings determine both the number of employees to be employed, as well as what kind of qualifications the employees should have. However, there were several testimonies, according to which the user undertakings are often mainly interested in the number of employees and secondarily to their qualifications. User undertakings are more interested in having enough people to work and are less interested in their educational background (see Appendix C).

Regarding the sixth criterion-question, about whether the working hours are the same or almost the same with the working hours of the permanent staff of the user undertaking (e.g., as with the hours of permanent employees or supervisors, etc.), 95.7% of the population answers that their working hours are exactly the same as the working hours of the permanent staff of the user undertaking (95% c.i.: 92.5–98.8%) and only 4.3% answered negatively (95% c.i.: 1.2–7.4%). The fact that an employee works together with the permanent staff of the user undertaking for the same or almost the same working hours is another proof of leased staff.

The seventh criterion-question was about whether the contract of the contracted employees mentioned a general description of the project (e.g., administrative support, data entry, etc.) and whether they receive more instructions/orders for the service from the user undertaking. Our entire population (100%) answer that their contract states a general description of the project, and they received more detailed instructions from the user undertaking. In practice, when the employee’s contract mentions a general description of the work to be performed and they receive more information from the user undertaking, this is strong evidence of leasing employees.

With regard to the eighth criterion-question, about whether the duration of the project as well as the type of tasks covered by the contracted workers in the user undertaking concern permanent tasks, which are part of the main activity of the user undertaking and previously were performed by their permanent staff, our entire population (100%) of contracted workers in the banking sector replied that this is exactly the case. Therefore, all the employees agree that they cover permanent needs of the user undertaking, and previously these tasks were performed by the permanent staff. This is evidence of a pseudo-contracting agreement, as the project should have an expiry date.

According to the testimonies of the employees they have been working for years in the same job, with the same responsibilities. They are not aware of the exact project/service provision that has been agreed between the contracting enterprise and the user undertaking. These facts constitute further proof that the majority of the employees cover permanent needs in the user undertaking. The above conclusions derive from interviews during the qualitative research and are part of the explanatory sequential mixed methods that we have used in our study (see Appendix C).

As characteristically reported by employees:

Employee: “The contracting business I work for, renews project contracts with the Banks and their subsidiaries every year. However, the tasks assigned to us have been the same for many years. The only thing that changes is the name of the project”.(employee T., aged 37)

Employee: “We don’t know what the project is. For years, we sit at the same work station in the user undertaking and do the same things that the user undertaking assigns to us”.(employee M., aged 45)

Regarding the ninth criterion-question, about whether the user undertaking assigns to the contracted workers other tasks or additional work other than those initially assigned to them, and which are not described in detail in their contract, 89.2% of the workers answer positively (95% c.i.: 85.0–93.4%) and only 10.8% answer negatively (95% c.i.: 6.5–15.0%). Therefore, this is another proof that these people are “pseudo-contracted” workers, as contracted employees are informed about their duties from the start.

Regarding the tenth criterion-question, i.e., whether the contracted workers believe that the contracting enterprise they work for lacks the necessary organization, logistical infrastructure and know-how to carry out projects in different companies and across different sectors, 99.6% answered negatively, i.e., that a company is not possible to have a suitable workforce in all specialties, for all companies and in all sectors (95% c.i.: 98.9–100%) and only 0.4% of the population answers that they do not know. Therefore, the answers to this question provide, in our opinion, a proof that employees are “pseudo-contracted”, as in practice the contracting businesses simply operate to lease workers and not to provide services, given that they do not have the necessary organization, logistical infrastructure, and know-how to carry out projects in different companies and in different sectors.

Regarding the eleventh criterion-question, which asks whom the contracted workers report to in the event that a problem arises during or upon completion of the project, 99.7% of the population said they report to the user undertaking (95% c.i.: 99.1–100%), and only 0.3% answered that they report to the contracting business. According to the criteria provided in the jurisprudence and labour law, when the employees report to the user company and not to the contractor regarding the progress or completion of the project, then this indicates that the personnel is leased. Also, it is worth underlining that according to the law, the responsibility for the deficiencies and possible problems arising in a project or service should be assumed by the contracting enterprise when there is no pseudo-contracting (Table 6). See Appendix A.

Table 6.

Criteria for the distinction of leasing and “pseudo” contract agreement.

It is also worth mentioning that 59.2% (95% c.i.: 51.9–66.4%) of the population has received training, even at a superficial level, from the user undertaking. The latter proves that on the one hand their real employer is the bank and on the other hand that the contracting enterprise and the bank enter into “pseudo contracts” (Table 7).

Table 7.

Training program of contracted employees.

According to the criteria set in the literature and our empirical research, we think that it is strongly indicated that contracted workers in the Banking Sector in Greece are pseudo-contracted and leased workers. It is also proven that the contracting enterprises, that provide services for the banking sector, enter into “pseudo” project contracts and essentially operate as TWAs.

Another interesting finding of our empirical study is that the net monthly remuneration for full-time contracted (who now can be called pseudo-contracted) workers, working at the premises of the banks for the year 2019, was 728.06 € (under either an indefinite or fixed term contract), including all the additional amounts (benefits, continuous service, overtime, shifts, etc.). The average working hours were 7.5 h/day, and the average employment was 9 years. As far as the part-time contracted workers are concerned, the monthly salary was 494.24 € (under either an indefinite or fixed term contract). The working hours were an average 5 h/day, and the mean duration of employment was 6.5 years (See Table 8 and Figure 3).

Table 8.

Net monthly salary of contracted employees of the Banking Sector *.

Figure 3.

Net monthly salary of contracted employees of the Banking Sector.

In order to make a payroll comparison between “pseudo-contracted” and permanent bank employees (including both forms the benefits, continuity and additional pays for shifts, overtime etc.), a separate survey was needed, with random sampling among the permanent bank employees. This has been a research restraint, however at this period this was not one of our priority research objectives. However, taking into account the sector-level collective agreement of Bank Employees for the year 2019, a permanent worker is entitled to a base salary of 945.00 €/month (payroll scale 0, no work experience, plus benefits, etc.) and up to 1.149.00 €/month (payroll scale 33, with work experience plus benefits, etc.).

The minimum salary provided by law for a “pseudo-contracted” employee in 2019 is 650 €/month, when single, without work experience, whereas a permanent employee with the specialty of bank employee, based on the sector-level agreement of bank employees, at the 0 payroll scale is paid 945 €/month, which means a 45% difference between the two types of employees. However, one should take into account the benefits of permanent employees that play an important role, increase the base salary, and determine the legal salary. These benefits concern previous years of employment (state), marriage benefit, children benefit, etc. Consequently, the payroll differences between the contracted and the “pseudo-contracted” workers and the permanent employees are much higher.

According to our research, both the Chairman of the Association of Leased Personnel in the Banking Sector (SYDAPTT) and the workers that we have interviewed during the qualitative part of the research claimed that the difference in the salary between the pseudo-contracted and the permanent personnel is approximately double or even more (see Appendix B and Appendix C).

Pay inequality between pseudo-contacted and permanent employees is not related to the educational background of the workers. On the contrary, contracted workers are often more qualified than the permanent employees. The main cause for this discrepancy is the form of employment itself. The wages of the contracted workers are determined based on the national general collective labour agreement, whereas those of the permanent personnel are set based on the sector-level collective labour agreement.

These claims, in combination with the differences in wages among the permanent personnel (based on the minimum wage provided by the sector-level collective agreement) and “pseudo-contracted” workers (based on the national minimum wage provided by law), clearly explain the reason why the above enterprises (banks and contractors) choose to bypass the law on workers leased through TWAs.

The reduction of the cost of wages is only one of the financial benefits the banks gain through this practice. Other gains for the banks stem from avoiding increased insurance contributions and benefits in kind (which are numerous for permanent bank employees), not to mention the limited trade union power of the “pseudo-contracted” workers.

5. Conclusions

Flexible forms of employment constitute a reality in the modern days and are expected to gain more and more ground in the near future in Europe.

This article studied and compared two flexible forms of employment. First, the leased workers through TWAs, and secondly, the contracted workers that are employed at the premises of the Banks (i.e., in-house outsourced workers). Employers use these forms of employment mainly as a way to reduce labour cost, increase flexibility, and raise productivity and competitiveness.

In this paper, our aim was to showcase the main characteristics of these flexible forms of employment in order to acquire deep comprehension and make the distinction. This can help workers in Europe avoid the practice of “pseudo-contracting” and being deceived by employers.

One of the key findings of the empirical research is that these workers turned out to be “pseudo-contracted” and, in reality, leased workers, and that the contracting enterprises usually operate illegally as TWAs, bypassing the European Directive and Greek laws. Another important conclusion of this research is that the remuneration inequalities between “pseudo-contracted” and permanent workers are high. Consequently, our research assumptions were confirmed.

The main characteristic of the leased workers through TWAs is the employer dualism. However, in practice, the results of our research showed that even in the phenomenon of contracting there are two “informal” employers. Specifically, there is one actual and one “virtual” employer. The official employer, i.e., the contracting enterprise is “virtual” and the user undertakings-Banks appear to be the real employer, given that they exercise managerial and supervisory rights over contracted employees.

In our opinion, it is very clear that the criteria-characteristics set by the theoretical literature, the laws, and the jurisprudence, which have been incorporated in the questionnaire of our research, provide a strong indication of “pseudo-contracting”.

The largest part of “pseudo-contracted” workers was identified in Athens, followed by smaller numbers in Thessaloniki and Patras, since most contractors and user undertakings operate in Athens.

The highest percentage of “pseudo-contracted” workers are women, single, university graduates, with an average age of thirty-eight, and the majority of the “pseudo-contracted” population works in a sector other than that of their specialization. The vast majority of the population have signed indefinite term contracts, however fixed-term contracts also exist. The average employment time of employees with indefinite term contract is ten years and of employees with fixed-term contract renewals almost four years. The “pseudo-contracted” employees, both under indefinite and fixed-term contracts, cover permanent needs of the user undertaking and the majority of this population does not switch to permanent staff of the Banks, but remains “trapped” in the “pseudo-contracting” phenomenon.

The practice of “in-house outsourcing” in the Greek banking sector applied by the employers leads to the avoidance of hiring permanent personnel or leasing personnel through the TWAs, where wage and work equality is provided between the leased and permanent employees based on Law 4052/2012. The use of pseudo-contracted workers leads to lower wages and less worker rights by avoiding relevant legislation and ultimately creates two categories of workers (permanent and pseudo-contracted workers) within enterprises, who, while working in the same workplace and collaborating, have completely different employment conditions and rights. This method of employing external workers undoubtedly amplifies labour market segmentation. It creates two types of employees in the same workplace, increasing the profitability of businesses at the expense of labour rights and in a way that violates the provisions of the law.