Abstract

This empirical study on employee perspectives of latent leader value orientations (LVOs), employee psychological job states, and work intentions deployed an online survey to 944 employees within global organizations. Empirical analysis using structural equation modeling confirmed that employee job state positive affect fully mediated relations between LVOs and employee work intentions more so than employee job state negative affect and cognitive-based and affective-based trust in leader. LVO1 (low self-concern and high other-orientation) triggered positive employee psychological job states of greater magnitude than LVO2 (high self-concern and high other-orientation). This finding offers new insight relating to the influence of high leader other-orientation on employee psychological experiences of work considering LVO2 had been reported as ideal. LVO3 (high self-concern and low other-orientation) had the strongest differential associations with employee psychological job states implying that leaders who are perceived by employees to be driven by high self-concern, even in the presence of low other-orientation, evoke strong negative employee psychological responses. Implications for theory and practical strategies to develop leader other-orientation in organizations are presented.

1. Introduction

Social value orientation (SVO; or social motive) is one’s preference for personal versus collective needs, interests, and outcomes in interdependent situations (McClintock 1972; Messick and McClintock 1968). SVOs are typically stable and comprise degrees of two individual motives: self-concern, an individual’s preference for personal power, and success, and a desire to achieve personal outcomes at the expense of the outcomes and needs of others (De Dreu and Carnevale 2003; Van Lange 1999); and other-orientation, a force which compels an individual to value others’ feelings, welfare, needs, and outcomes more so than valuing one’s own (De Dreu and Carnevale 2003; Van Lange 1999). Social dilemma researchers have identified two primary SVOs: A pro-self orientation (high self-concern and low other-orientation), defined as an individual’s preference to allocate a higher weight to one’s own needs and outcomes compared to those allocated to others in interdependent situations (De Dreu and Carnevale 2003; Van Lange 1999); and a pro-other (or pro-social) orientation (high self-concern and high other-orientation), typified by an individual’s preference to maximize equality between self and others’ needs and outcomes and the pursuit of fairness and harmony in interdependent situations (De Dreu and Carnevale 2003; Van Lange 1999).

Researchers have reported behavioral outcomes associated with pro-self and pro-other orientations. For example, recent meta-analyses (e.g., Andrighetto et al. 2020; Pletzer et al. 2018) revealed that pro-self and pro-other orientations have differential effects on cooperation in interdependent situations. A meta-analysis by De Dreu et al. (2000) involving 28 independent samples found that pro-social individuals engaged in problem solving, less contentious behavior, and achieved higher joint outcomes more so than did pro-self individuals. Grant and Mayer (2009) reported evidence that manager trustworthiness moderated relations between employee pro-other motives and performance. Nonetheless, calls to investigate individual motives in socially interdependent situations have been consistent. For example, Kollock (1998) commented that “different social value orientations are theoretically possible, but most work has concentrated on various linear combinations of individual’s concern for the outcomes for themselves and their partners” (p. 192). De Dreu (2006) called for research to “test the validity that very different and seemingly opposing models predict psychological processes and organizational behavior simultaneously when participants have high self-concern as well as high other-orientation, and that neither has any predictive validity when participants have low self-concern as well as low other-orientation” (p. 1250). Egan et al. (2019) observed that their methodology “did not allow for the understanding of the impact of self-concern and other-orientation in combination” (p. 334) and called for examination of this topic. This study responds to these calls.

1.1. Leader Social Value Orientation

Social psychological experiments (e.g., McClintock 1972; Messick and McClintock 1968; Van Lange 1999) have demonstrated linkages between an individual’s SVO and their thoughts, feelings, and behavior in interdependent settings. In the domain of leadership, De Cremer (2000) asserted that “Social value orientation may be used as an additional variable in examining how leaders acquire legitimacy, support and good relations” (p. 336). Aligning with these theoretical precedents, we propose that a leader’s SVO is a behavioral manifestation of a personal preference for the distribution of outcomes between self and interdependent others (e.g., employees). We contend that pro-self leaders demonstrate a greater concern for their aspirations and needs when allocating resources and making decisions to the detriment of others in interdependent situations. We also contend that pro-other leaders seek group collaboration and achievement when allocating resources and making decisions in the pursuit of collective objectives and simultaneously seek to fulfill their own aspirations and needs.

Empirical scrutiny of leader SVOs is in a nascent stage of development. For example, De Cremer’s (2002) experiment concluded that pro-other leaders demonstrated greater charisma than pro-self leaders and the former were more likely to promote group cooperation. Van Dijk and De Cremer (2006) reported that pro-self leaders allocated a greater number of scarce resources to themselves than did pro-social leaders. Notwithstanding, Bolino and Grant (2016) concluded that “there has been a paucity of research on prosocial motives among teams, entrepreneurs, and leaders” (p. 22). Grant and Sumanth (2009) remarked, “We hope that researchers will examine whether particular combinations of prosocial motivation and trust cues [manager trustworthiness] result in different levels of performance. These mediating mechanisms should be examined” (p. 942). Haynes et al. (2015a) asserted that “A balance between self-interest and concern for others is likely the best approach for most managers” (p. 275). To the best of our knowledge, we believe few, if any, studies have empirically tested this proposition. The present investigation responds to these calls by analyzing the antecedent nature of leader SVOs and associations with outcome covariates.

1.2. Employee Perspectives of Leader Social Value Orientations

A deep vein of research has highlighted the essential role of followers in determining leader effectiveness (e.g., Atwater et al. 2009; Bass 2008; House 1971). Scholars have also demonstrated value in understanding others’ perceptions when assessing leader behavior and styles (e.g., Atwater et al. 1998; Harris and Schaubroeck 1988). In terms of perceptions of leader SVOs, Rubenstein et al. (2020) concluded “Although supervisors may be able to accurately introspect as to their own motives…there are differences between supervisors’ ratings of their own motives and newcomer [employee] perceptions of supervisor motives” (p. 15). Egan et al. (2017) stated that “measuring employees’ perceptions of leaders’ value-driven behavior is a largely unexplored and potentially beneficial methodology” (p. 21). Hence, we believe tapping the perceptions of those influenced by leadership (i.e., employees) will provide greater insight into the psychological effects that may arise from leaders’ SVOs in action. Given this is a largely unexplored methodology, it offers a novel perspective of leader-employee relationships.

1.3. Leader Social Value Orientations and Employee Psychological Responses

A core tenet of Cognitive Appraisal Theory (CAT; Lazarus 1991; Lazarus and Folkman 1984; Zajonc 1984) postulates that individuals mentally connect their past and present environmental experiences to their values, emotions, and expectations to form future intentions and coping behaviors (Lazarus 1991; Lazarus and Folkman 1984). Appraisals can be conceptualized in two phases. First, individuals cognitively appraise their environment, including events and interpersonal exchanges, and determine whether these stimuli have personal relevancy. Affect triggered by the appraisal then manifests in an evaluation of personal well-being (Lazarus and Folkman 1984). Second, individuals form intentions that lead to coping behaviors stemming from perceptions of the environment’s positive or negative impact on their personal well-being (Lazarus and Folkman 1984).

Roseman (1984) contended that different types of appraisals, e.g., the extent to which an event is (in)consistent with one’s motives, probability, agency, motivational states, and power, elicit different emotions. Zajonc (1984) concluded that “It is emotional reactions that categorize the environment into safe and dangerous classes of objects and events” (p. 122). Lazarus (1991) contended that when individuals describe an emotional experience, they do not always report a single emotion generated from a single event, rather, they cite a series of emotions organized around “appraisal patterns and core relational themes” (p. 819). Frijda (1993) argued that when a series of related subevents are the objects of appraisal, the appraiser remains in a state of “continuous emotional engagement”.

In organizations, leader effectiveness is, to a large extent, determined not only by a leader’s personal agency but by the perceptions, reactions, and behaviors of interdependent others, e.g., followers, coworkers, and superiors (Atwater et al. 2009; Bass 2008; House 1971). Applying CAT to the workplace, we propose that behavioral manifestations of a leader’s SVO are the object of employee appraisals. For example, an employee could appraise their leader to be continuously promoting their personal needs, preferences, and aims “through deception, strategic withholding of information, and spinning of information” (De Dreu et al. 2008, p. 26), and conclude their leader has a pro-self orientation. In contrast, an employee could appraise their leader to be always striving to maintain group harmony and consensus in the pursuit of collective goals whilst seeking to fulfill their personal ambitions and needs and conclude their leader demonstrates a pro-other orientation. In alignment with CAT, we suggest that as a result of employee appraisals of their leader’s SVO, the personal significance of the social exchange becomes clear when an employee senses that one’s well-being is at stake, e.g., “assaults on personal pride, violations of wishes and expectations, personal losses” (Lazarus and Folkman 1984, p. 272). Employee emotionality, and, in turn, the adoption of coping behaviors results. The present study examined employee perceptions of their leader’s SVOs and hypothesized associations with employee psychological states and employee work intentions. The constructs used to gauge employee psychological states in this study are discussed next.

1.3.1. Job State Affect

Scholars have contended that cognition and affect are “inextricably linked” when individuals perceive and respond to their organizational environment and both are critical in shaping responses to stimuli within it (Forgas and George 2001; Zajonc 1984). Affect experienced during appraisals are reflections of one’s evaluation of personal well-being (Lazarus and Folkman 1984) and include state affects (in-the-moment, short-term emotional experiences) and trait affects (stable emotional preferences that are a dimension of personality) (Watson and Tellegen 1985). In this study, to avoid blurring inferences with dispositional affect, we followed precedents in the literature and analyzed employee job state affect (cf. Zigarmi et al. 2012).

In the work environment, employee job state affect has been found to have differential impacts on employee behavioral outcomes including creativity (Madjar et al. 2002), job satisfaction (Connolly and Viswesvaran 2000), and performance (Damen et al. 2008). Few studies have empirically explored leader SVOs, follower emotions, and outcome variables (Agote et al. 2016; Chen et al. 2021). As such, key questions remain unanswered: Do employee perceptions of leader SVOs meaningfully relate to employee positive and/or negative job state affect? Does employee positive and/or negative job state affect perform explanatory mechanisms linking leader SVOs and employee work intentions? We sought to answer these questions.

1.3.2. Affect-Based Trust and Cognition-Based Trust in Leader

Interpersonal trust is a key psychological element that entwines leader–follower relationships (Dirks and Ferrin 2002; Fulmer and Gelfand 2012). In McAllister’s (1995) seminal work on cooperation in organizations, interpersonal trust is defined as “the extent to which a person is confident in, and willing to act on the basis of, the words, actions and decisions of another” (p. 25). McAllister (1995) identified two types of interpersonal trust: Affective trust, which encapsulates the emotional bonds between trustor and trustee where care and concern are reciprocated; and cognitive trust, which is grounded in tangible evidence of competence, reliability, and responsibility. This study adopted these definitions.

Various scholars reported that general trust in leaders mediated respective relations between other-orientated leadership styles such as transformational leadership and servant leadership and various outcomes, e.g., employee affective organizational commitment and job performance (Zhu et al. 2013), team psychological safety and team potency (Schaubroeck et al. 2011), and organizational citizenship behaviors (OCB; Nohe and Hertel 2017). Zigarmi et al.’s (2018) canonical analysis found that both logical and emotional forms of trust in leader “play a significant role in the formation of general trust” (p. 35). We note that Schaubroeck et al. (2011) opined that “Some studies have examined leadership antecedents of trust in the leader and others have examined the outcomes of such trust, there has been little consideration of the mediating role of trust in the leader” (p. 868). Gooty et al. (2010) identified that “The role of trust and emotions in leading and following is under-researched … less research attention has focused upon affective influences in trusting one’s leader” (p. 1000). The present study responds to these calls and those of others (e.g., Yang and Mossholder 2010; Zhu et al. 2013) by empirically examining the extent to which both employee affective and cognitive trust in leader may mediate relations between leader antecedents of trust and work intentions.

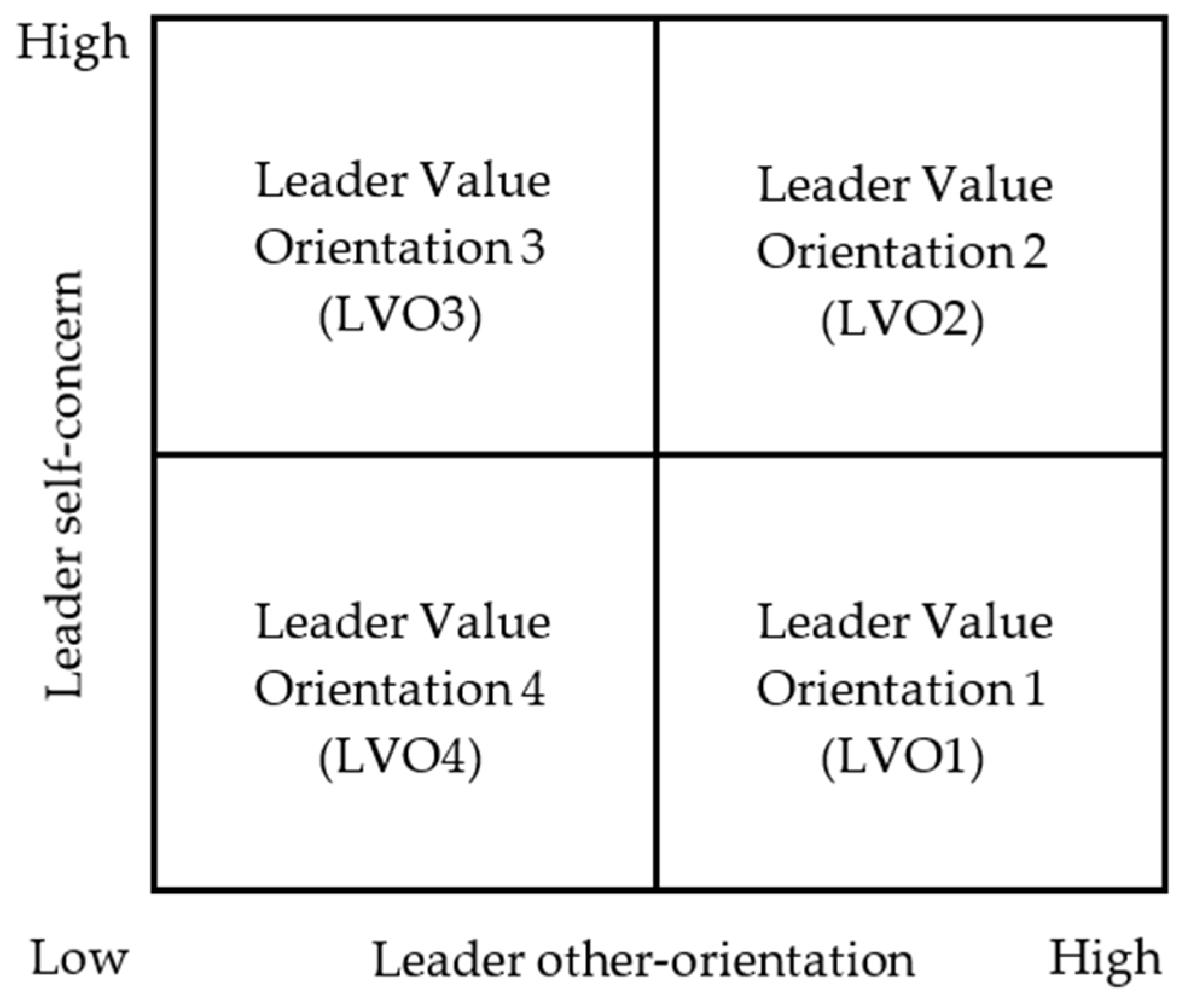

In terms of study design, we deployed an exploratory approach and extrapolated the theoretical underpinnings of SVOs to the domain of leadership. First, we established the validity of all focal constructs and analyzed relations between employee perceptions of leader self-concern and leader other-orientation (as individual constructs) and respective associations with endogenous constructs, i.e., employee positive and negative job state affect, employee affective and cognitive trust in leader, and work intentions. Second, we scrutinized employee perceptions of four dichotomized leader value orientations (LVOs; see Figure 1), i.e., LVO1 (low leader self-concern and high leader other-orientation), LVO2 (high leader self-concern and high leader other-orientation), LVO3 (high leader self-concern and low leader other-orientation), and LVO4 (low leader self-concern and low leader other-orientation), and respective associations with the endogenous constructs measured in step 1.

Figure 1.

Leader value orientations.

1.4. Study Purpose

Research has focused primarily on two SVOs: Pro-self (high self-concern and low other-orientation) and pro-other (high self-concern and high other-orientation). Notwithstanding, numerous scholars, e.g., De Dreu (2006), Grant and Sumanth (2009), and Egan et al. (2019), have appealed for an investigation of SVOs in the domain of leadership. This study responds to these appeals by proposing that leader self-concern and leader other-orientation combine to form four latent LVOs (see Figure 1). Furthermore, we acknowledge that a central theme in CAT relates to the role of cognition and affect in the quality of social exchange (Lazarus 1991; Lazarus and Folkman 1984; Zajonc 1984), e.g., between leader and follower. Accordingly, CAT formed the theoretical foundation of this study as we believe it to be an appropriate lens through which to examine employee appraisals of leader SVOs and impacts on the subjective psychological states and behavioral intentions of the appraiser.

This study’s overarching purpose was to empirically examine employee perspectives of their immediate leader’s SVO and hypothesized associations with employee psychological job states and employee work intentions. We chose to examine focal constructs exclusively from the perspective of the recipients of leadership, i.e., followers, because, without followers, leaders are not needed. As such, we sought to uncover a more nuanced understanding of the nature of employees’ psychological experience of work. We believe this to be a novel methodology and insights gained will contribute to addressing current limitations in the extant SVO and leadership literatures and the development of relevant nomological networks and theory building.

Considering implications for organizational practice, we draw attention to the following. During the last two decades, organizational development and management consultants (e.g., Chiu and Salerno 2019; Dinwoodie et al. 2015) and scholars have posited that global organizational competitiveness relies to a large extent upon an organization’s commitment to continuous learning (Moldoveanu and Narayandas 2019), innovation (Darwish et al. 2020), and transformational renewal and change (Parker 2016). We suggest that at least three groups of constituents, i.e., leaders, employees, and Human Resource Development (HRD) practitioners, perform critical roles in strategies needed to respond to these challenges. Key leader competencies must include the self-regulation and management of emotions, stimulating creativity in others, and leading people through the implementation of organizational change whilst maintaining employee engagement. Moreover, leaders need to overtly communicate to employees that leadership is a dynamic process and mutual success relies on each party’s willingness to bring their whole self to work each day in a spirit of collaboration. Of equal importance is the ability and willingness of employees to regulate and manage their emotions, identify and seek out psychological needs satisfaction, challenge the status quo, provide candid feedback, and willingly collaborate with leaders and peers alike. Employees may perceive some of these behaviors to be personally risky and leaders’ communication styles can convey contrasting messages relating to consequences stemming from employee interpersonal risk taking (Newman et al. 2017). Additionally, workplace climates characterized by the absence of perceived negative consequences of personally risky behaviors do not emerge quickly or innately (Eva et al. 2019).

To combat these headwinds, we believe that HRD practitioners need to remain steadfast in their pursuit of the key purpose of HRD, i.e., shaping, articulating, and amplifying organizational cultures through “strategic decision making related to workforce training, professional and leadership development, organizational change and knowledge management” (Kuchinke 2010, p. 576). Not least amongst these responsibilities is the development of workplaces that are permeated with thoughtfully calibrated leadership behaviors, which are less about self-focused leaders pursuing personal agendas and aggrandizement and more about leaders’ willingness to share wisdom, demonstrate sensitivity to the emotional and motivational dimensions of followers, and focus on the developmental and performance-oriented needs of others. Scholars have suggested that building the capability to systematically develop these behaviors at scale, amongst globally dispersed populations, is challenging (Anderson and Sun 2017). To assist in the arrestment of this challenge, this study offers organizational stakeholders perspicacity relating to the degree and direction in which employee perceptions of leader SVOs may activate employee psychological states and impact on employee work intentions. Such knowledge will assist stakeholders in operationalizing practical strategies to create humanistic and business-oriented outcomes.

Following this, we present a review of academic literature relevant to leader social value orientations, job state affect, affective and cognitive forms of trust in leaders, and work intentions and rationale for hypothesized relations. Study method, results, implications for organizational practice, limitations, and directions for future research are discussed.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Social Value Orientation

The social psychological theory of SVO (McClintock 1972; Messick and McClintock 1968) postulates that “individuals differ in their approaches, judgments, and responses regarding others with whom they are interdependent” (Van Lange 1999, p. 337). In a quest to achieve personal success at the expense of others’ success the motivational impetus of self-concern is displayed in egoistic and competitive behaviors (Schilling 2009; Schmid et al. 2019). Other-orientation drives an individual to pursue joint inputs and outcomes and collective success (De Dreu et al. 2008). These preferences influence how individuals make decisions and behave in interdependent situations (Van Lange 1999).

Leadership driven by high self-concern has been found to have deleterious effects on interdependent others (De Cremer 2002, 2006; Haynes et al. 2015a, 2015b) including reduced employee affective commitment and increased counterproductive behavior (Mao et al. 2019) and decreased pro-social behavior in teams (Liu et al. 2017). Other-orientated leadership has been positively associated with increased cooperation by interdependent others (De Cremer 2002), employee positive affect, need fulfillment, job satisfaction, and OCB (Bolino and Grant 2016). Marinova and Park’s (2014) meta-analysis of the impacts of other-orientated leadership included 151 effect sizes and uncovered support for it in individual (trust in leader, leadership effectiveness, positive organizational support, fairness, job satisfaction, OCB), group (justice climate and performance, group deviance), and organization (organizational effectiveness) domains.

When considering self-concern and other-orientation in combination, researchers have distinguished two primary SVOs: Pro-self orientation, which manifests in individuals who seek to maximize their own outcomes with little or no regard for those of others; and pro-social orientation, which drives individuals to maximize outcomes for self and others (De Dreu 2006; De Dreu et al. 2008; Van Lange 1999). These SVOs help explain differences in individual motivations and behaviors in interdependent situations such as negotiation (De Dreu et al. 2000), conflict (Pruitt and Rubin 1986; Thomas 1992), leadership (Blake and Mouton 1964), and power (McClelland 1970; Winter 1973). For instance, considering leader preferences for the use of power, McClelland (1970) and Winter (1973) conceptualized interactions between self-serving (personalized) and other-serving (socialized) forms. Leaders with high personalized power motivation and low socialized power motivation seek recognition and adulation and coerce others. Leaders who are low in personalized power motivation and high in socialized power motivation work towards improving the welfare of others, e.g., providing educational opportunities or healthcare benefits. Leaders high in both power motivations are simultaneously motivated by a desire to benefit others and by the prestige and benefits associated with their position. Leaders who are low in both types of power motivation are not sustained by outcomes stemming from their influence because they perceive them as being personally unimportant. Such conceptualizations of power, together with organizational models of negotiation, conflict, and leadership, contribute to the theoretical foundation adopted in this study, i.e., leaders vary in their self-concern and independently in their other-orientation.

In terms of leaders demonstrating an amalgam of self-concern and other-orientation motives through their behavior, Haynes et al. (2015b) stated that “the most effective leaders find the tipping point between self-interest and concern for others, and carefully manage that balance over time” (p. 275). Bolino and Grant (2016) argued that “High prosocial motivation coupled with high self-concern appears to generate the most sustainable contribution” (p. 17). Overall, however, empirical investigations into the extent to which pro-self and pro-other orientations (or any other combination of self-concern and other-orientation) demonstrate in leaders are few. Thus, while controlling for gender, organization tenure, and organization level, we propose that employee perceptions of:

Hypothesis 1a.

Leader other-orientation is negatively and moderately related to leader self-concern.

Hypothesis 1b.

Leader value orientations (LVO1, LVO2, LVO3, and LVO4) are negatively related.

2.2. Leader Self-Concern, Leader Other-Orientation, and Job State Affect

An individual’s appraisal of their environment, i.e., persons, objects, and situations, comprises cognitive and affective elements (Lazarus 1991; Lazarus and Folkman 1984; Zajonc 1984). Job state affect describes the (un)conscious emotions generated during primary appraisals of one’s workplace and perceived differential impacts on the appraiser’s sense of well-being (Lazarus and Folkman 1984). The type, quality, direction, and intensity of job state affect depends on the meaning and perceived personal implications derived from the appraisal (Lazarus and Folkman 1984).

Two dominant dimensions of state affect are positive affect demonstrated by emotions such as happiness, enthusiasm, and energy, and negative affect displayed by emotions such as sadness, fear, and nervousness. Watson and Tellegen (1985) developed the Positive Affect and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS), a two-factor model consisting of state affective dimensions. The majority of organizational studies measuring state affect used the PANAS to measure positive/negative activation (Thompson 2007). Aligning with this precedent, we deployed the International Positive and Negative Affect Schedule–Short Form (I-PANAS-SF; Thompson 2007) to measure job state positive and negative affect because we believe employee appraisals of LVOs are likely to trigger different valenced employee emotions.

Researchers established that broadly other-focused leadership behaviors, e.g., transformational leadership (see Connelly and Ruark 2010) and supervisor-focused justice behaviors (see Colquitt et al. 2013) are positively related to employee state affect. In contrast, relations between self-focused leadership and employee state positive affect have typically been negative. For example, Schmid et al. (2019) found that exploitative leadership was negatively related to employee affective organizational commitment and positively related to employee stress and burnout. Zigarmi and Roberts (2012) found that manager self-concern and manager other-orientation were differentially associated with positive and negative affect. We agree with these and other authors (e.g., De Cremer 2006; Grant 2012) who argued that leaders perceived to have high other-orientation are sensitive to the emotional dimensions of followers and invest their time in fostering relationships with them and engender employee job state positive affect. We concur with scholars (e.g., Haynes et al. 2015a, 2015b; Mao et al. 2019) who contended that leaders high in self-concern use power to promote their own aims and subordinate those of others and are likely to activate employee job state negative affect. In alignment with these precedents, we propose that while controlling for gender, organization tenure, and organization level, that employee perceptions of:

Hypothesis 2a.

Leader other-orientation is positively related to positive affect and negatively related to negative affect.

Hypothesis 2b.

Leader self-concern is positively related to negative affect and negatively related to positive affect.

Hypothesis 2c.

LVO1 is positively related to positive affect and negatively related to negative affect.

Hypothesis 2d.

LVO2 is positively related to positive affect and negatively related to negative affect.

Hypothesis 2e.

LVO3 is positively related to negative affect and negatively related to positive affect.

2.3. Leader Self-Concern, Leader Other-Orientation, and Trust

Fulmer and Gelfand (2012) drew attention to the importance of delineating the referent or “target of the trust (i.e., the trustee)” (p. 1170). For example, when considering one-on-one relationships, the target or referent of trust could be a leader, peer, or colleague and each could be associated with “divergent antecedents and consequences due to changing relational dynamics across referents” (Fulmer and Gelfand 2012, p. 1170). Given this study’s purpose, this section is focused on potential differential associations between employee appraisals of LVOs (as trust referents) and employee trust in leader.

Research has highlighted that leadership behaviors and styles have strong and positive associations with measures of employee trust in the leader. For instance, Dirks and Ferrin’s (2002) meta-analysis involving 106 independent samples revealed that transformational leadership, transactional leadership, and justice measures had positive associations with cognitive trust and overall trust in leader. Others reported that narcissistic leadership (Yao et al. 2019) and destructive leadership (Schyns and Schilling 2013) were negatively associated with employee trust in leader. Schaubroeck et al. (2011) and Zhu et al. (2013) concluded that the antecedents to, and consequences of, affective trust and cognitive trust are distinct. Our review of the SVO and leadership literature did not uncover any studies that investigated associations between leader self-concern, leader other-orientation (individually or in combination), and emotional and logical forms of trust in leader.

We propose that it is likely that leaders perceived by employees to be high in leader other-orientation will foster employee affect-based trust due to their demonstrable concern for the welfare and needs of employees thereby strengthening emotional bonds between the parties. These same leaders will likely engender employee cognition-based trust due to their demonstration of personal competence, acts of integrity, and displays of reliability and dependability. We suggest that leaders who are solely focused on their personal needs and seek to maintain a competitive advantage at the expense of human and social capital (Haynes et al. 2015b) will elicit negative associations with both employee affective and cognitive trust in leader. Thus, while controlling for gender, organization tenure, and organization level, we propose that employee perceptions of:

Hypothesis 3a.

Leader other-orientation is positively related to affect-based trust and cognition-based trust.

Hypothesis 3b.

Leader self-concern is negatively related to affect-based trust and cognition-based trust.

Hypothesis 3c.

LVO1 is positively related to affect-based trust and cognition-based trust.

Hypothesis 3d.

LVO2 is positively related to affect-based trust and cognition-based trust.

Hypothesis 3e.

LVO3 is negatively related to affect-based trust and cognition-based trust.

2.4. Affect and Intentions

According to CAT, emotions relating to perceived positive or negative impacts on personal well-being are triggered when individuals appraise events, situations, or people (Lazarus 1991). Secondary appraisals relating to the “options and prospects for coping” (Lazarus 1991, p. 827) then take form. Gollwitzer (1999) defined intentions as mental representations of potential actions and coping behaviors an individual might deploy to regulate emotional appraisals. Intentions can be categorized in two groups: End goals and behavioral means that will enable goal fulfillment (Webb and Sheeran 2006). Meta analyses (e.g., Webb and Sheeran 2006) have reported evidence that intentions are reliable predictors of actual behavior. Accordingly, in this study we used Nimon and Zigarmi’s (2015) measures of five work intentions (i.e., intent to engage in discretionary effort, intent to perform at higher-than-average levels, intent to endorse the organization as a positive place of work, intent to stay with the organization, and intent to engage in OCB) to gauge employee behavioral intentions associated with employee appraisal of their leader.

Meta analytical studies within the job attitudes literature (e.g., Ng and Sorensen 2009; Thoresen et al. 2003) found positive correlations between positive affect and job satisfaction, affective commitment, job significance, and job autonomy, and positive correlations between negative affect and emotional exhaustion, job stress, depersonalization, work overload, and turnover intentions. Scholars (e.g., Egan et al. 2019; Zigarmi and Roberts 2012) reported differential associations between positive affect, negative affect, and employee work intentions, respectively, and that positive affect had stronger effects on employee work intentions compared to those emanating from negative affect. Thus, while controlling for gender, organization tenure, and organization level, we propose that employee perceptions of:

Hypothesis 4a.

Positive affect is positively related to work intentions.

Hypothesis 4b.

Negative affect is negatively related to work intentions.

Hypothesis 4c.

Positive affect is more strongly related to work intentions than is negative affect.

2.5. Trust and Intentions

General measures of trust in leader have been found to predict positive job attitudes including follower risk taking, task performance, and OCB (Colquitt et al. 2007; Nohe and Hertel 2017) and been inversely related to job attitudes such as counterproductive work behavior (Colquitt et al. 2007). Considering relations between employee logical and emotional forms of trust in leader and outcome variables, Dirks and Ferrin’s (2002) reported positive associations with organizational commitment, OCB, job performance, and job satisfaction, respectively, and both were negatively associated with intent to quit. Schaubroeck et al. (2011) reported independent effects stemming from employee affect-based and cognition-based trust in leader and team potency and team psychological safety, respectively. Zigarmi et al. (2018) revealed that affective and cognitive trust-based canonical functions accounted for 35% and 85% of the explained variance in work intentions, respectively. By extension, while controlling for gender, organization tenure, and organization level, we propose that employee perceptions of:

Hypothesis 4d.

Affect-based trust in leader and cognition-based trust in leader are positively related to work intentions, respectively.

2.6. Leader Self-Concern, Leader Other-Orientation, Affect, and Intentions

Cognitive assessment, emotions, and coping strategies are key elements of the appraisal theory (Lazarus 1991; Lazarus and Folkman 1984). Emotions infuse experience with valence and, as such, color the outcome of the appraisal process (Forgas and George 2001). Scholars have reported that emotional states such as employee state affect mediate relations between leadership behaviors and employee outcome measures including follower task performance (Colquitt et al. 2013), job satisfaction (Lambert et al. 2012), and OCB (Chen et al. 2021). Manager self-concern and manager other-orientation were found to have indirect effects on work intentions via employee state affect (Zigarmi and Roberts 2012). Thus, we propose that while controlling for gender, organization tenure, and organization level, that employee perceptions of:

Hypothesis 5a.

Leader other-orientation and leader self-concern will indirectly and completely impact work intentions through positive and negative affect.

Hypothesis 5b.

LVOs will indirectly and completely impact work intentions through positive affect and through negative affect.

2.7. Leader Self-Concern, Leader Other-Orientation, Trust, and Intentions

Follower trust in leader is a significant mediator of relations between other-oriented leadership styles (e.g., transformational leadership, servant leadership) and employee behavioral outcomes. For example, Nohe and Hertel’s (2017) meta-analysis involving 761 independent samples revealed that employee trust in leader partially mediated positive relations between transformational leadership and OCB. Miao et al. (2014) reported that affective and cognitive trust in leader fully mediated relations between servant leadership and organizational commitment, respectively. Lu et al. (2019) found that the indirect effect of servant leadership on employee surface/deep acting via affective trust was stronger than the indirect effect via cognitive trust. Overall, empirical analysis of the explanatory mechanisms that employee logical and emotional forms of trust in leader may play in relations between leader self-concern, leader other-orientation, and employee work intentions, respectively, is underdeveloped. Thus, the following hypotheses are primarily exploratory. While controlling for gender, organization tenure, and organization level, employee perceptions of:

Hypothesis 5c.

Leader other-orientation and leader self-concern will indirectly and completely impact work intentions through affect-based and cognition-based trust.

Hypothesis 5d.

LVOs will indirectly and completely impact work intentions through affect-based and cognition-based trust.

3. Method

3.1. Participants

The study sample was generated from a USA-based management training and development organization’s marketing database. Approximately 25,000 employees in organizations within private, government, and non-profit sectors received an email invitation to participate in an online survey, a data collection vehicle deemed appropriate because it could tap a global population and promoted respondent anonymity (Dillman et al. 2009). Participation was voluntary, no incentives were offered, informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study, and they could abandon the survey at any time. In total, 2045 surveys were completed. Data were screened for missing data, unengaged respondents, univariate and multivariate outliers, and normality. The final sample was 944. All data were examined using SPSS (version 28.0) and AMOS (version 28.0). The sample consisted of 38% male and 62% female; 12% were under 40 years of age, 65% were between 40 and 59 years, and 23% were over 60 years; 33% were individual contributors and 67% were leaders. For organizational experience, 45% had 5 or fewer years, 41% had between 6 and 19 years, and 14% had 20 or more years. Furthermore, 72% were located in the USA/Canada, 13% in EMEA, 11% in APAC, and 4% in Latin/South America.

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Self-Concern and Other-Orientation

Scales for self-concern and other-orientation (De Dreu and Nauta 2009) measured employee cognitive perceptions of their immediate leader’s frequent demonstration of these behaviors. Each scale contained three descriptive items and a five-point anchored scale (5 = very much to 1 = not at all). A sample item of self-concern was “My leader considers his/her own wishes and desires to be more relevant”. A sample item of other-orientation was “My leader considers the wishes and desires of others to be more relevant than his/her own”. The respective alpha reliability coefficients for self-concern and other-orientation scales in this study were 0.85 and 0.92 (see Table 1).

3.2.2. International Positive and Negative Affect Schedule–Short Form (I-PANAS-SF)

Thompson’s (2007) I-PANAS-SF measured employee positive and negative affect. The I-PANAS-SF comprised two 5-item mood scales containing words that describe positive affect, i.e., alert, inspired, determined, attentive, and active, and negative affect, i.e., upset, hostile, ashamed, nervous, and afraid, and a five-point anchored scale (5 = always to 1 = never). Affect items were prefaced with: “Indicate the extent to which these words describe your feelings about your job”. The respective alpha reliability coefficients for positive and negative affect scales in the present study were 0.89 and 0.83 (see Table 1).

3.2.3. Affect-Based and Cognition-Based Trust

McAllister’s (1995) affect-based trust and cognition-based trust scales were used and included a seven-point anchored scale (7 = strongly agree to 1 = strongly disagree). Affect-based trust in leader was measured by five items, e.g., “If I shared my problems with my leader, I know he/she would respond constructively and caringly”. Cognition-based trust in leader was measured by six items, e.g., “I can rely on my leader not to make my job more difficult”. Alpha reliability coefficients for both trust measures in this study were 0.95 (see Table 1).

3.2.4. Work Intention Inventory–Short Form (WII-SF)

Nimon and Zigarmi’s (2015) WII-SF measured five employee work intentions, i.e., intent to use discretionary effort, intent to perform, intent to endorse the organization, intent to stay in the organization, and intent to use OCB. All scales included three items and a six-point anchored scale (6 = to the fullest extent to 1 = to no extent). Items were prefaced with: “To what extent do the following statements reflect how you intend to behave while performing within your organization?”. Alpha reliability coefficients for the work intention scales in this study ranged from 0.82 to 0.95 (see Table 1).

3.3. Procedures

3.3.1. Research Design

SVOs have typically been measured using self-report data (cf. Wong et al. 2010), yet self-ratings of value-driven behaviors are prone to suffer from social desirability biases (Podsakoff et al. 2003). This study, therefore, incorporated employee perceptions of their leader’s SVOs. Given that the four focal employee psychological constructs represent subjective, internal states of the appraiser, we aligned our design with Boxall et al.’s (2016) assertion that employee phenomenological states be “assessed by employees themselves” (p. 108). We agree with Zigarmi et al.’s (2012) contention that behavioral intentions are “bi-products” of employees’ evaluation of their experience of their work environment. Hence, employee self-ratings of their work intentions were gathered.

3.3.2. Common Method Variance (CMV)

To alleviate concerns related to CMV that could result from self-reported data describing variables relating to emotions, attitudes, and behavioral intentions (MacKenzie and Podsakoff 2012), we implemented the following procedural and analytical practices. Survey design: Valid and reliable measures and multiple-item measures for all variables were incorporated (Aguinis and Vandenberg 2014); a variety of response formats and frequency-anchored rating scales were used; and items within constructs were randomized (Lindell and Whitney 2001). Survey administration process: The research purpose was clearly conveyed; respondent data were anonymous; and respondents could abandon the survey at any time (Dillman et al. 2009). Statistical procedures: Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to scrutinize the data (Maxwell and Cole 2007); given the a priori hypothesized models included multiple mediators, specific indirect effects were estimated using bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals (Preacher and Hayes 2008; Rungtusanatham et al. 2014); and Williams et al.’s (2010) “confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) marker technique” was implemented to detect method variances that could cause inflation or deflation of observed relations leading to Type 1 and II errors (Podsakoff et al. 2003). Specifically, a theoretically unrelated marker variable using items measuring aspects of the respondent’s work environment behavior (i.e., daily commute time) was created. Marker variable items were rated on a ten-point anchored rating scale (1 = 0–10% of the time to 10 = 91–100% of the time). Subsequently, a series of models were tested following Williams et al.’s (2010) guidelines.

3.3.3. Control Variables

To minimize the risk that examined relations could be confounded due to respondent demographics, control variables including gender (1 = male, 2 = female), organizational tenure (in years), and organizational level (1 = leader, 2 = non-leader) were included in substantive analyses. Previously, these demographic variables have been statistically associated with this study’s focal constructs, e.g., self-concern and other-orientation (see De Dreu and Nauta 2009), trust (see Madjar and Ortiz-Walters 2009; Zhu et al. 2013), discretionary effort (see Peyton and Zigarmi 2021), job performance (see Ho et al. 2011), and OCB (see McAllister et al. 2017; Zhu et al. 2013).

3.3.4. Statistical Analysis—Phase 1

Descriptive statistics were calculated. To examine the latent factor structure within the data, measurement models and structural models were scrutinized (Anderson and Gerbing 1988). CFA followed Hair et al.’s (2010) guidelines and included the following sequential analyses: First, each of the 11 hypothesized latent factors was examined for construct validity. Second, an a priori hypothesized 11-factor measurement model (CFA1) was assessed for construct validity: The assessment of convergent validity included (a) acceptable model fit, (b) significant standardized factor loadings (SFLs; ≥0.70), (c) factor composite reliability (CR; ≥0.60), and (d) factor average variance extracted (AVE; >0.50) (Fornell and Larcker 1981). Discriminant validity was analyzed by assessing each factor, i.e., maximum shared variance (MSV) < AVE, average shared variance (ASV) < AVE, and the square root of AVE > than any inter-factor correlation (Fornell and Larcker 1981). In addition, discriminant validity was investigated using the heterotrait–monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT; a comparison of the heterotrait–heteromethod correlations and the monotrait–heteromethod correlations) where required (Henseler et al. 2015). Third, CFA1 was tested for evidence of CMV utilizing Williams et al.’s (2010) confirmatory factor analysis marker technique: (1) A CFA marker model that included the theoretically unrelated marker variable was tested. This model comprised 12 factors where all factor loadings from the marker variable to the substantive variable items were set to 0; (2) a baseline model was tested where the correlations between the method and substantive latent variables were set to 0 and the unstandardized regression weights and variances for the marker variable were fixed to the values obtained from the CFA marker model; (3) a constrained model (Model-C) where the factor loadings from the latent marker variable to the substantive factor items were constrained to be equal was analyzed; (4) an unconstrained model (Model-U) where the factor loadings from the latent marker variable were freely estimated was tested; (5) a restricted model (Model-R) in which the substantive factor covariances from Model-U were set to their values from the baseline model was tested.

Structural model fit and validity were calculated as follows: (1) Model fit for SEM1, a completely mediated model without control variables, was assessed and then compared with that of CFA1. (2) Model fit for SEM2, a completely mediated model with control variables as exogenous constructs regressed on all endogenous constructs, covaried with exogenous constructs, and covaried with each other, was compared to that of CFA1. (3) Model fit for SEM3, an alternative model with control variables that included all paths in SEM2 plus direct paths from each of the two exogenous variables to each of the work intention variables (10 in total), was compared to that of SEM2 to see if this partially mediated model explained the data better than SEM2. (4) Following the precedent in the literature (see Preacher and Hayes 2008), the significance of individual indirect effects in the final structural model was assessed using effect decomposition analysis that incorporated bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals (n = 2000, confidence intervals set at 95%). An indirect effect is considered significant at p < 0.05 if zero is not included in its 95% confidence interval (Rungtusanatham et al. 2014). The magnitude of indirect effects was gauged as small (0.01), medium (0.09), and large (0.25) (Preacher and Kelley 2011).

3.3.5. Statistical Analysis—Phase 2

We created a dichotomized indicator representing “low” and “high” groups for self-concern and other-orientation scales by splitting the data at the median (DeCoster et al. 2009; Iacobucci et al. 2015). For the self-concern scale: “low” group n = 415 (44%) and “high” group n = 529 (56%) and for the other-orientation scale: “low” group n = 408 (43%) and “high” group n = 536 (57%). We then created four dichotomous exogenous variables each comprising combinations of self-concern and other-orientation (see Figure 1). Descriptive statistics were calculated including an analysis of biserial correlations between dichotomous exogenous and continuous endogenous variables (Field 2013).

In SEM, when nonmetric exogenous variables have K levels, K − 1 variables are needed as the fourth variable functions as a reference point in interpreting the dummy variables (Hair et al. 2010; Rosseel 2014). Thus, we specified a 12-factor measurement model (CFA2) comprising three latent dichotomous exogenous variables (LVO1, LVO2, and LVO3) and all endogenous variables from CFA1. LVO4 was selected as the exogenous reference variable given that it was uncorrelated with all endogenous variables with the exception of OCB (r = −0.07, p < 0.05, see Table 7).

Structural analysis was as follows: (1) Model fit for SEM4, a completely mediated model with control variables, was compared with that of CFA2. (2) Model fit for SEM5, an alternative partially mediated model with control variables that included all paths in SEM4 plus direct paths from each of the three exogenous variables to each of the work intention variables (15 in total), was compared to that of SEM4 to investigate if a partially mediated model explained the data better than SEM4. (3) Model for SEM6, a partially mediated model with control variables that included all paths estimated in SEM4 plus all significant direct paths from exogenous variables to work intention variables that were uncovered in SEM5 (six in total) was compared to that of SEM4. (4) The significance of individual indirect effects in the final structural model was assessed using effect decomposition analysis following procedures outlined in Statistical analysis—Phase 1.

4. Results

4.1. Phase 1

4.1.1. Descriptive statistics

Means, standard deviations, intercorrelations, and reliability coefficients were aligned with the theory and provided support for all hypothesized relations (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, correlations, and reliabilities.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, correlations, and reliabilities.

| Variable | M | SD | SC | OO | PA | NA | ABT | CBT | IDE | IP | IS | IE | IOCB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SC | 3.54 | 1.01 | (0.85) | ||||||||||

| OO | 3.50 | 1.12 | −0.61 | (0.92) | |||||||||

| PA | 3.56 | 1.00 | −0.46 | 0.72 | (0.89) | ||||||||

| NA | 1.74 | 0.77 | 0.51 | −0.70 | −0.68 | (0.83) | |||||||

| ABT | 4.56 | 1.88 | −0.60 | 0.80 | 0.68 | −0.69 | (0.95) | ||||||

| CBT | 5.04 | 1.69 | −0.60 | 0.79 | 0.67 | −0.71 | 0.85 | (0.95) | |||||

| IDE | 3.95 | 1.21 | −0.28 | 0.44 | 0.51 | −0.39 | 0.40 | 0.41 | (0.82) | ||||

| IP | 5.24 | 0.85 | −0.17 | 0.32 | 0.40 | −0.28 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.46 | (0.89) | |||

| IS | 3.58 | 1.59 | −0.44 | 0.61 | 0.63 | −0.59 | 0.63 | 0.62 | 0.45 | 0.38 | (0.93) | ||

| IE | 4.54 | 1.34 | −0.37 | 0.54 | 0.56 | −0.53 | 0.53 | 0.54 | 0.48 | 0.50 | 0.70 | (0.95) | |

| IOCB | 5.46 | 0.72 | −0.12 | 0.27 | 0.33 | −0.22 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.35 | 0.61 | 0.32 | 0.46 | (0.87) |

SC: Self-concern, OO: Other-orientation, PA: Positive affect, NA: Negative affect, ABT: Affect-based trust, CBT: Cognition-based trust, IDE: Intent to use discretionary effort, IP: Intent to perform, IS: Intent to stay, IE: Intent to endorse the organization, IOCB: Intent to use OCB. N = 944. All correlations significant at p < 0.01 (2-tailed). Cronbach’s alpha internal-consistency reliability coefficients appear in parentheses along the main diagonal.

4.1.2. Measurement Models

For each of the 11 individual measurement models, competing measurement models were examined and results supported acceptable construct validity. For each factor, fit indices indicated that multi-factor correlated models fit the data better than single-factor models (in the interest of parsimony these results are not included). For CFA1, all variables were measured by three or more item indicators (Hair et al. 2010), SFLs ranged from 0.72 to 0.97 and were significant, and goodness-of-fit statistics were acceptable (see Table 2). Overall, CFA1 goodness-of-fit statistics and indices indicated an acceptable model fit.

Table 2.

Measurement models’ and structural models’ goodness-of-fit statistics.

Within CFA1, for each construct, CR was > 0.70 and AVE was > 0.50, which suggested an acceptable level of convergent validity (see Table 3). Adequate discriminant validity was evident with the exception of negative affect (see Table 3). Henseler et al. (2009) and Hair et al. (2012) advised that when the Fornell–Larker criterion fails to support discriminant validity, further assessment of cross-loadings is warranted. Hence, HTMT correlation ratios for all factors were calculated and deemed acceptable (in the interest of parsimony, these results are not included). Additionally, since affect-based trust and cognition-based trust were highly correlated statistically, we estimated the following trust models to further scrutinize measurement model fit: A one-factor model (with all 11 items loading on a single trust latent variable) and a two-factor model (with all items loading on to affect-based and cognition-based trust, respectively). Evidence supported the two-factor model fit compared to that of the single-factor model (Δχ2 [1] = 522.853, p < 0.001). The two-factor model fit indices were more acceptable than those of the single-factor model, thus, affect-based trust and cognition-based trust factors were retained. In sum, acceptable levels of discriminant validity were found within CFA1.

Table 3.

Measurement model convergent and discriminant validity through AVE and factor correlation analysis.

Table 4 details the model fit indices of the CFA marker models. There was shared CMV between the indicators of the substantive variables and the latent marker variable evidenced by Model-C (constrained) offering significantly better fit than the baseline model. Model-U (unconstrained) fit the data better than Model-C, which indicates that CMV was not constant for all indicators. Model-R (restricted) was not statistically significantly different from Model-U suggesting the presence of CMV did not bias relations among the substantive variables (cf. Williams et al. 2010). In conclusion, CFA results supported the a priori hypothesized model.

Table 4.

Model fit indices and model comparisons for CFA models with marker variable.

4.1.3. Structural Models

Model fit for SEM1 indicated an acceptable goodness-of-fit (see Table 2). Items factor loadings were above the minimum threshold and significant (Hair et al. 2010). The comparative assessment of model fit between SEM1 and CFA1 revealed the following: (1) The χ2 value for SEM1 showed a significant increase in value from that of CFA1 (Δχ2 [14] = 47.755, p < 0.05) (see Table 2). (2) Fit indices for SEM1 were not substantially different from those of CFA1 (see Table 2). (3) SEM1 SFLs compared to those from CFA1 revealed inconsequential differences ranging from 0.001 to 0.004 in absolute value (Hair et al. 2010) implying there was no evidence of interpretational confounding of constructs, which supports structural model validity. Overall, SEM1 model fit changed little from the CFA1 fit. The only substantive difference was a chi-square difference of 47.755 and a difference of 14 degrees of freedom, which was significant. SEM1 strongly suggested adequate structural fit. Model fit for SEM2 revealed an acceptable goodness-of-fit (see Table 2). When comparing SEM2 model fit to CFA1 model fit, the only substantive difference was a significant increase in χ2 (Δχ2 [83] = 117.331, p < 0.05) (see Table 2). The analysis of path estimates between control variables and endogenous constructs (i.e., a total of 27) revealed that seven were significant. Only one correlation between control variables and exogenous variables was significant. Notably, by including control variables in SEM2, the overall model fit and the significance of relations did not alter. Overall, the magnitude and direction of hypothesized relations were not altered significantly in SEM2. However, considering the significant relations between control variables and endogenous work intention constructs, control variables were retained in all subsequent analyses. Model fit for SEM3 revealed an acceptable goodness-of-fit (see Table 2). The Δχ2 statistic showed a statistically insignificant decrease in value from that of SEM2 (Δχ2 [10] = 10.401, p > 0.05). SEM3 fit indices were inconsequentially different from those of SEM2. We concluded that SEM3 did not demonstrate a statistically significant improvement in model fit compared to that of SEM2. Bootstrapped standardized direct effects were estimated for SEM3 and none of the 10 additional direct paths were significant. Overall, evidence supported SEM2.

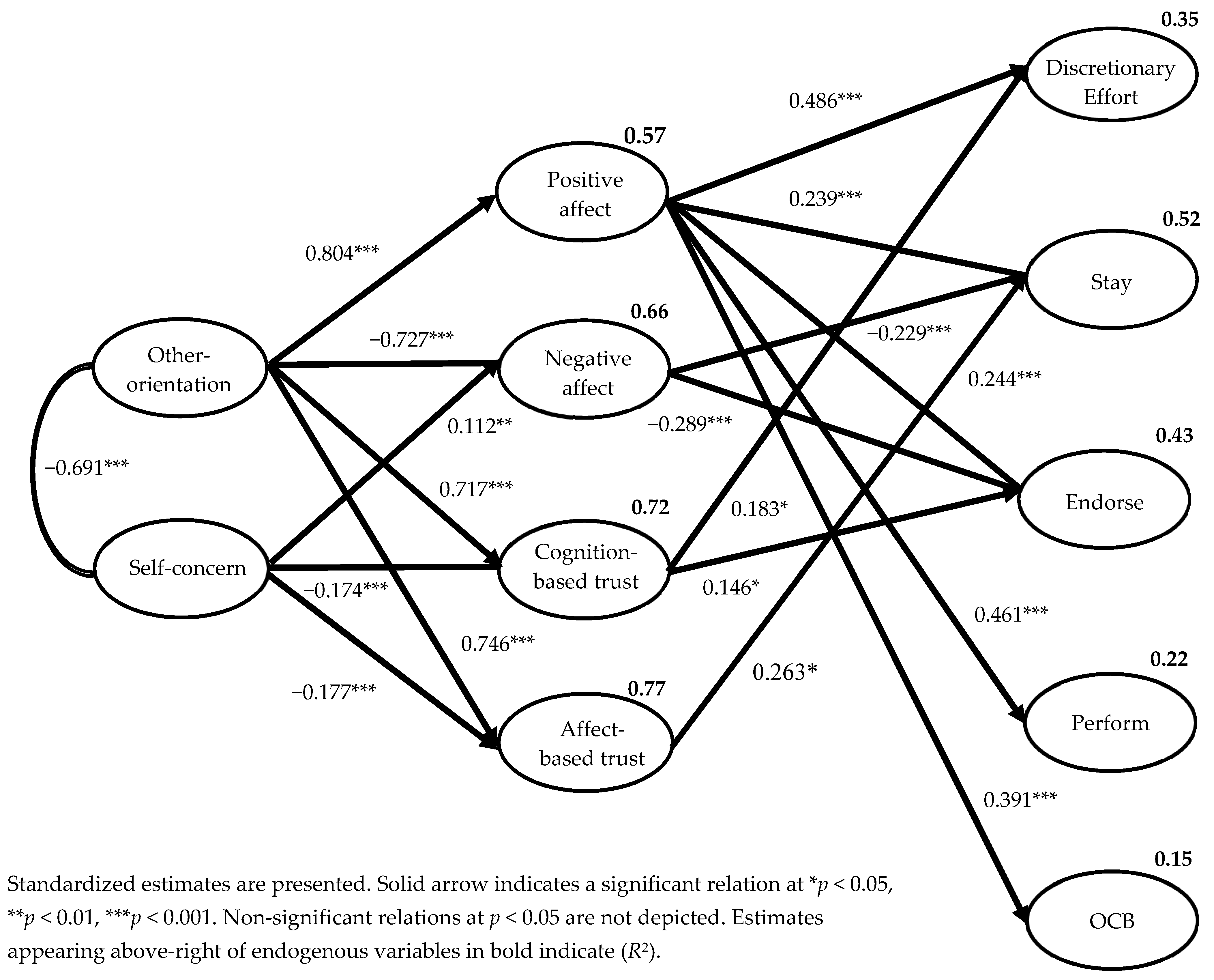

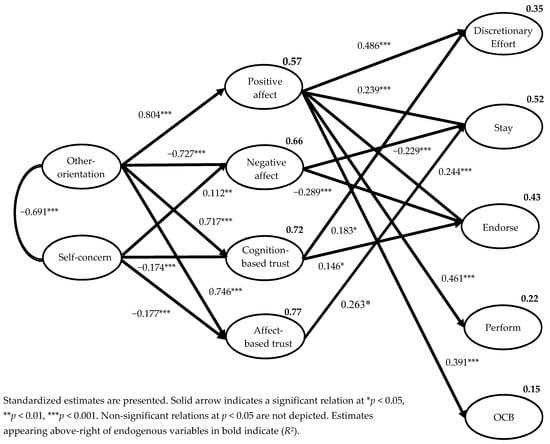

4.1.4. SEM2 Interpretation

SEM2 is illustrated in Figure 2. As expected, self-concern and other-orientation were significantly, moderately, and negatively correlated confirming H1a. Other-orientation was differentially associated with positive affect (β = 0.804, p < 0.001), affect-based trust (β = 0.746, p < 0.001), cognition-based trust (β = 0.717, p < 0.001), and negative affect (β = −0.727, p < 0.001). These results confirmed H2a and H3a. Self-concern was differentially associated with negative affect (β = 0.112, p < 0.01), affect-based trust (β = −0.177, p < 0.01), and cognition-based trust (β = −0.174, p < 0.01) as expected. Self-concern and positive affect were unrelated, which was inconsistent with the bivariate correlation (r = −0.46, p < 0.01) and the correlation coefficient in CFA1 (r = −0.47, p < 0.001). Thus, H2b was partially supported and H3b was supported. Positive affect was positively associated with each work intention (βs ranged from 0.239 to 0.486, all ps < 0.001) providing support for H4a. Considering that two out of five paths between negative affect and work intentions were significant (β = −0.289 and β = −0.229, ps < 0.001), H4b was partially supported. Positive affect predicted employee work intentions more strongly than negative affect. Thus, H4c was confirmed. One path between affect-based trust and work intentions was positive (β = 0.263, p < 0.001) and two of the paths between cognition-based trust and work intentions were positive (β = 0.146 and β = 0.183, ps < 0.05). Thus, H4d was partially supported. Noting the size, direction, and significance of covariance and structural relations, an adequate level of validity within SEM2 was evident.

Figure 2.

Structural Model 2 depicts employee positive affect, negative affect, affect-based trust, and cognition-based trust completely mediating the relations between other-orientation and self-concern and work intentions.

4.1.5. Effect Decomposition Analysis

Individual indirect effects indicated that positive affect mediated relations between other-orientation and work intentions and between self-concern and work intentions, respectively (see Table 5). The largest individual indirect effect was leader other-orientation on intent to engage in discretionary effort through positive affect (BE = 0.417, p = 0.001). Thus, H5a was partially supported. Individual indirect effects indicated that affect-based trust mediated respective relations between other-orientation, self-concern, and intent to stay in the organization (see Table 6). Individual indirect effects indicated that cognition-based trust mediated respective relations between other-orientation, self-concern, and intent to engage in discretionary effort, and self-concern and intent to endorse the organization (see Table 6). The largest individual indirect effect was between other-orientation on intent to stay in the organization via affect-based trust (BE = 0.279, p = 0.001). Thus, H5c was partially supported. Overall, phase 1 data demonstrated sufficient validity to enable phase 2 analysis to proceed.

Table 5.

SEM 2—Specific indirect effects of other-orientation and self-concern on work intentions through positive affect and through negative affect.

Table 6.

SEM 2—Specific indirect effects of other-orientation and self-concern on work intentions through affect-based trust and through cognition-based trust.

4.2. Phase 2

4.2.1. Descriptive Statistics

All intercorrelations were aligned with theory and were supportive of hypothesized relations (see Table 7).

Table 7.

Means, standard deviations, and biserial correlations.

4.2.2. Measurement Models

CFA2 SFLs were significant and ranged from 0.72 to 0.97. Goodness-of-fit statistics were acceptable (see Table 2). Thus, the CFA2 model fit was acceptable. Considering that dichotomous exogenous variables were derivatives of leader self-concern and leader other-orientation variables and all endogenous variables were those from CFA1, CFA2 convergent and discriminant validity were deemed acceptable (see Table 3).

4.2.3. Structural Models

Model fit for SEM4 indicated an acceptable goodness-of-fit and SFLs were significant and above 0.70 (Hair et al. 2010). The comparative assessment of SEM4 model fit and CFA2 model fit included the following: (1) The χ2 value for SEM4 showed a significant increase from that of CFA2 (Δχ2 [76] = 309.990, p < 0.05) (see Table 2). (2) SEM4 fit indices were not substantially different from those of CFA2 (see Table 2). (3) SEM4 SFLs compared with those from CFA2 revealed minor differences ranging from 0.001 to 0.007 in absolute value (Hair et al. 2010). Thus, no problem was evident due to the interpretational confounding of constructs, which supports structural model validity. SEM4 model fit changed very little from that of CFA2. The only substantive difference was a chi-square difference of 309.990 and a difference of 76 degrees of freedom, which was significant. Model fit for SEM5 revealed an acceptable goodness-of-fit (see Table 2). The Δχ2 statistic showed a statistically insignificant decrease in the value from that of SEM4 (Δχ2 [15] = 18.705, p > 0.05) (see Table 2). SEM5 fit indices showed only minor changes when compared to those of SEM4. Given the non-significant Δχ2 difference test, SEM5 did not demonstrate a significant improvement in model fit. Bootstrapped standardized direct effects were estimated for SEM5, and 6 of 15 additional direct paths were significant albeit all weak in magnitude. Model fit for SEM6 revealed an acceptable goodness-of-fit (see Table 2). The Δχ2 statistic showed a statistically insignificant decrease in the value from that of SEM4 (Δχ2 [6] = 12.193, p > 0.05) (see Table 2). SEM6 fit indices showed immaterial changes from those of SEM4. Considering the non-significant Δχ2 difference test, SEM6 did not demonstrate a significant improvement in model fit compared to SEM4. According to the analysis of direct paths from exogenous constructs to work intention constructs, only the path from LVO1 to OCB was significant but low in magnitude (β = 0.100, p = 0.017). Overall, the results supported the more parsimonious model (SEM4) as hypothesized.

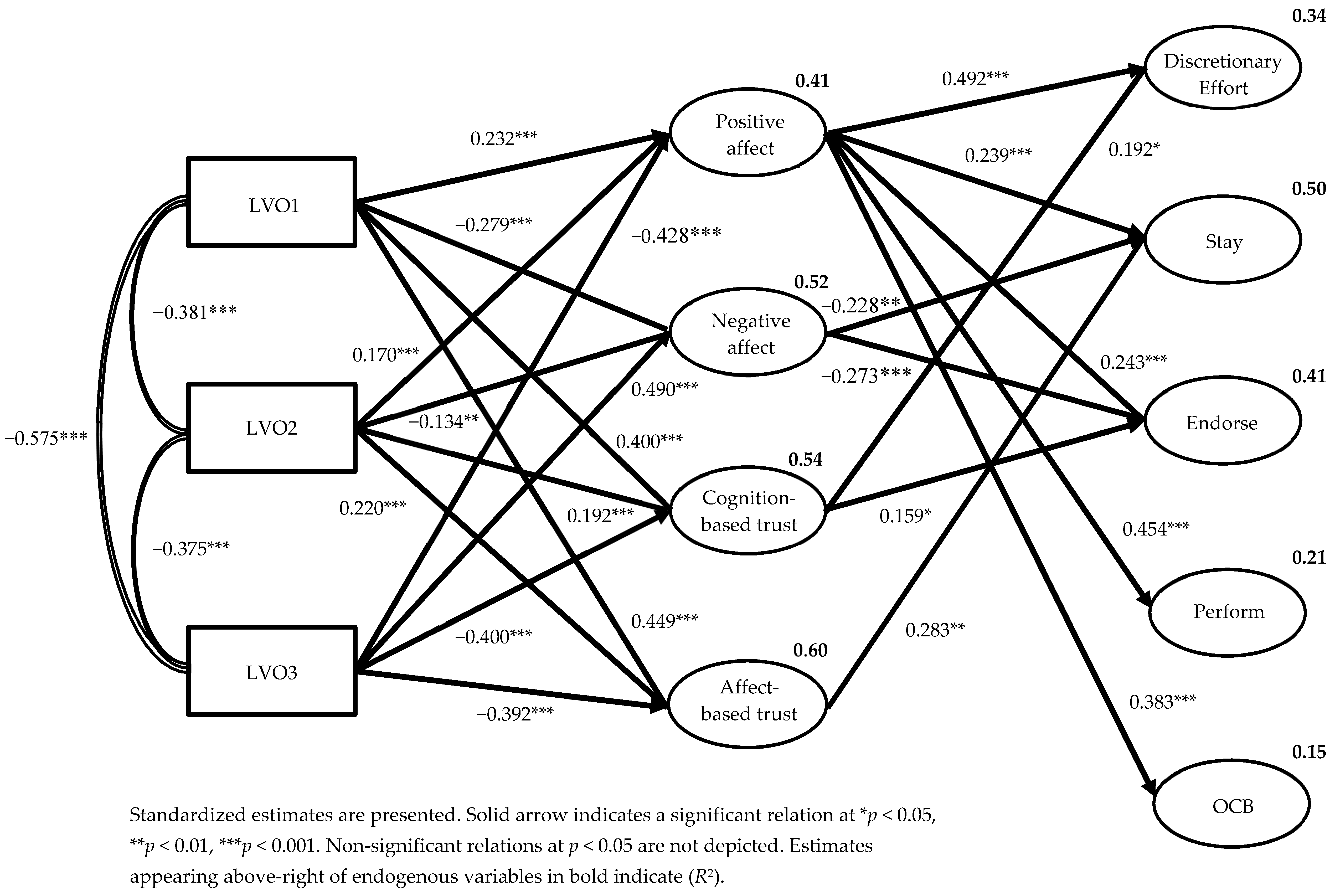

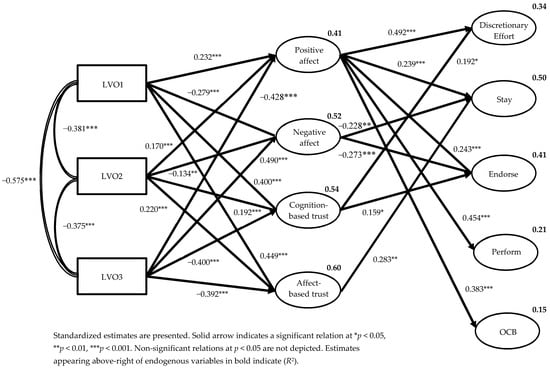

4.2.4. SEM4 Interpretation

SEM4 is presented in Figure 3. As hypothesized, LVO1 was significantly, moderately, and negatively correlated with LVO2 and LVO3, respectively. LVO2 was significantly, moderately, and negatively correlated with LVO3. Thus, H1b was confirmed. LVO1 was positively related to positive affect (β = 0.232, p < 0.001), affect-based trust (β = 0.449, p < 0.001), and cognition-based trust (β = 0.400, p < 0.001), and negatively related to negative affect (β = −0.279, p < 0.001). Thus, H2c and H3c were confirmed. LVO2 was differentially related to positive affect (β = 0.170, p < 0.001), affect-based trust (β = 0.220, p < 0.001), cognition-based trust (β = 0.192, p < 0.001), and negative affect (β = −0.134, p < 0.01). Thus, H2d and H3d were supported. LVO3 was differentially associated with negative affect (β = 0.490, p < 0.001), positive affect (β = −0.428, p < 0.001), affect-based trust (β = −0.392, p < 0.001), and cognition-based trust (β = −0.400, p < 0.001). Thus, H2e and H3e were confirmed. Respective paths between positive affect, negative affect, affect-based trust, cognition-based trust, and work intentions were all similar in significance, direction, and magnitude to those respective paths uncovered in SEM2 (see Figure 2 and Figure 3) and provided further support for our conclusions drawn about H4a, H4b, H4c, and H4d. Overall, the size, direction, and significance of covariance and structural relations provided an acceptable level of validity for SEM4.

Figure 3.

Structural Model 4 depicts employee positive affect, negative affect, affect-based trust, and cognition-based trust completely mediating the relations between leader value orientations and work intentions.

4.2.5. Effect Decomposition Analysis

The individual indirect effects that LVO1, LVO2, and LVO3 had on work intentions via positive affect are listed in Table 8. Negative affect mediated relations between all three exogenous constructs and intent to endorse the organization and intent to stay in the organization, respectively, and these effects were medium to large in size. Overall, individual indirect effects indicated that positive affect mediated relations between LVO1, LVO2, and LVO3 and work intentions more so than negative affect. Thus, H5b was partially supported. Affect-based trust mediated relations between LVO1, LVO2, and LVO3 and intent to stay in the organization, respectively, and these effects were large in size (see the top half of Table 9). Cognition-based trust mediated relations between LVO1, LVO2, and LVO3 and intent to endorse the organization and intent to engage in discretionary effort, respectively, and these effects were medium in size (see bottom half of Table 9). Thus, H5d was partially supported.

Table 8.

SEM4—Specific indirect effects of leader value orientations on work intentions through positive affect (top of the table) and through negative affect (bottom of the table).

Table 9.

SEM4—Specific indirect effects of leader value orientations on work intentions through affect-based trust (top of the table) and through cognition-based trust (bottom of the table).

5. Discussion and Theoretical Implications

This study analyzed employee perspectives of the antecedent nature of leader SVOs and associations with employee psychological states and employee work intentions. Phase 1 results revealed that 17 (out of 28) hypothesized paths were significant and in the anticipated direction. Phase 2 results indicated that 22 (out of 32) hypothesized paths were significant and in the anticipated direction. Taken together, the evidence from analyses of covariance and structural relations supported both a priori hypothesized models.

Phase 1 results indicated that the nature of the respective paths between leader self-concern, leader other-orientation, and the four mediating variables were as hypothesized, with a caveat for the path between leader self-concern and positive job affect. This non-significant path was unexpected considering this result was inconsistent with preliminary correlations (see Table 1 and Table 3) and with previous findings in which it was reported to be significant and negative (see Egan et al. 2019; Zigarmi and Roberts 2012). One explanation could be that this effect is a statistical artifact stemming from multicollinearity, which can become apparent at later stages of multivariate analysis (Hair et al. 2010). As such, we interpreted this relation cautiously. Overall, phase 1 results reified the proposition that leaders who are perceived by employees to be focused on others’ concerns and needs evoke employee job-related positive emotions (enthusiasm, high energy, alertness) and they were aligned with those reported previously (e.g., De Cremer 2006; Egan et al. 2019). They also provided support for the proposition that leaders perceived to be self-focused activate employee job-related negative emotions (anxiousness, frustration, hostility). This finding was aligned with those in the literature (e.g., De Cremer and Van Dijk 2005).

The positive and strong connections we uncovered between leader other-orientation and both emotional and logical forms of trust in leader support previous conclusions, e.g., Lu et al. (2019), Schaubroeck et al. (2011), and Zhu et al. (2013), who all reported positive associations between transformational leadership, and separately, servant leadership and emotional and logical forms of trust in leader. We found that leader self-concern was negatively associated with both measures of trust in leader (albeit the strength of these relations was low in magnitude), and these results corroborate those reported in the trust (e.g., Dirks and Ferrin 2002) and self-interest (e.g., Schyns and Schilling 2013) literature.

In relation to the mediating role of job affect (particularly in its positive form) between leader self-concern and leader other-orientation and work intentions, respectively, phase 1 findings align with those reported previously (e.g., Egan et al. 2019; Zigarmi and Roberts 2012). They add weight to the notion that leader other-orientation activates employees’ positive job-related emotions, which, in turn, are likely to positively impact employee willingness to engage in positive work intentions relating to both the job and the organization. The proposition that leader self-concern triggers employee negative job-related emotions, which, in turn, are likely to have negative impacts such as employees being less willing to endorse their organization as a place of work and to remain in its employment was supported.

Specific indirect effects of leader other-orientation on intent to stay in the organization via affect-based trust were strong in effect size and were medium in effect size on intent to engage in discretionary effort via cognition-based trust. These results confirm those reported in the trust literature (e.g., Nohe and Hertel 2017; Schaubroeck et al. 2011) and support the idea that leaders who advocate for the primacy of others’ needs engender in employees both emotional and logical forms of trust in their leader and some positive job and organizational work intentions result. The specific indirect effects of leader self-concern via affect-based trust on employee intent to stay in the organization and via cognition-based trust on intent to engage in discretionary effort and to endorse the organization were negative and medium in size. When employees perceive their leader to be self-focused, both emotional and logical forms of employee trust in leader are eroded and these psychological states are likely to translate into employees being unwilling to expend discretionary effort, to recommend their organization to others, and remain in its employment over the long term.

Phase 2 analyses revealed that three of the four hypothesized LVOs had significant statistical effects on employee psychological states as hypothesized. LVO1 and LVO2 were strongly related to each mediator as anticipated, and these results strongly support our contention that when employees appraise their leader as being primarily focused on others’ needs, positive employee psychological responses result. This finding aligns with those of previous investigations (e.g., Grant and Sumanth 2009; Sonnentag and Grant 2012). Notably, path coefficients between LVO1 and each mediator were stronger in magnitude than those between LVO2 and each mediator. This finding provides new insight inasmuch as it implies that when high leader other-orientation is coupled with high leader self-concern, it has a dampening effect on employee psychological job states. Of all latent LVOs, LVO3 had the strongest relations with each mediator and the path coefficient between LVO3 and negative job affect was the strongest of the 12 structural paths between exogenous and mediating constructs. These results mirror those in the self-interested leadership literature, e.g., self-concern was negatively related to employee positive affect (Schyns and Schilling 2013) and affective organizational commitment (Schmid et al. 2019) and positively related to employee job tension (Harvey et al. 2007). This finding implies that leaders who are driven by high self-concern, even in the presence of low other-orientation, evoke negative employee emotional responses.

The significant specific indirect effects between all three LVOs on work intentions via positive job affect, and to a lesser extent through negative job affect, support the hypothesized mediating roles of these emotionally ladened psychological job states. The magnitude and direction of specific indirect effects between LVOs and employee intentions to engage in discretionary effort, endorse the organization to others, and stay in its employment via employee emotional and logical forms of trust in leader highlight the integral role of employee trust in employee leader social exchange. Notwithstanding, we note that previous investigations reported that employee trust in their leader was positively associated with OCB (e.g., Nohe and Hertel 2017) and with job performance (e.g., Brower et al. 2009; Dirks and Ferrin 2002) and that our analyses did not confirm these findings. Interestingly, some authors (e.g., Wong et al. 2006; Yang and Mossholder 2010; Zhu et al. 2013) reported some non-significant relations between these constructs. For example, Zhu et al. (2013) concluded that respective relations between transformational leadership, OCB, and job performance were fully explained by affective-based trust but not by cognitive-based trust. Yang and Mossholder (2010) uncovered both (non)significant relations between affective and cognitive trust in supervisors and in-role and extra-role behavior, respectively. We recommend further examination of respective relations between LVOs, employee affective and cognitive forms of trust, OCB, and job performance.

Taken collectively, phase 2 findings have the following implications for theory. First, the explanatory roles of the four putative mediators of respective relations between LVOs and work intentions highlight their relative strengths. For instance, previous assertions (see Damen et al. 2008; Chen et al. 2021) that employee positive job state affect (more so than negative job state affect) is an integral function of leader–employee relationships were confirmed. Second, the notion that leaders are an important referent of follower trust was reinforced. As noted, the trust literature has focused primarily on the antecedents to and effects of cognition-based trust. Our results provide preliminary support for the contention that both logical and emotional forms of trust in leader help explain relationships between leaders’ social motives and employee work intentions, although we recommend further empirical investigation of these relations. Third, they reify De Dreu’s (2006) contention that “What matters is the degree to which employees are concerned with their own needs as well as the degree to which they are oriented toward the needs and ends of others” (p. 1245). Stated differently, our findings underline the importance of identifying the “mix of motives” that drive individuals’ behavior at work (Howard et al. 2016). Specifically, in response to assertions by scholars relating to beneficial outcomes associated with leaders who demonstrate a pro-other orientation (e.g., Bolino and Grant 2016; Haynes et al. 2015b), nuances clearly matter. For example, our results make clear that while LVO2 triggered differential effects on employee psychological job states, stronger impacts emanated from LVO1. Furthermore, the antagonistic nature of high leader self-concern, even when coupled with low leader other-orientation (i.e., LVO3), was evident. These findings add weight to Haynes et al.’s (2015b) assertion that “healthy or balanced amounts of self-interest have a beneficial influence but extreme amounts of it have negative effects” (p. 485). Although our findings pertaining to associations between LVOs and outcome covariates are preliminary, we believe they highlight the importance of (1) identifying the “mix of motives” that perform as internal drivers of leader behavior and (2) understanding associated psychological impacts on the recipients of leadership and their subsequent intentions to engage in coping behaviors.

6. Practical Implications