Abstract

The objective is analyzing the trends in Social Entrepreneurship Education as a multidisciplinary research field. A systematic review of the literature on the intersection: Education and Social Entrepreneurship, with the support of scientific literature and a careful search methodology. It collects articles from the WOS Core collection database published between 2000 and 2022. A total of 367 articles are analyzed to answer the three research questions. The results of the analysis are twelve dimensions identified according to the literature in the field of social entrepreneurship education; after using lexicometric analysis and Iramuteq software, the main trends on the topics are found and discussed and the relationship of terms and concepts in the abstract and title text of the analyzed articles is shown, showing the frequency, importance of linkage, and co-occurrences of lexical units. Six clusters of nodes and related terms are confirmed: entrepreneur, development and innovation, education, entrepreneurial university, context, and types of study. These clusters show the concern for the field of study of social entrepreneurship education and the need to find a consensus on the concept of an entrepreneur and on what is social entrepreneurship in education. The wide range of topics, dispersed and fragmented, continues to offer opportunities for specificity.

1. Introduction

Entrepreneurship has become a preferred field of study because of its direct impact on progress (Carree et al. 2002), following the traditional theories related to economic development (Shane and Venkataraman 2001). In recent decades, all public policy has revolved around promoting this human activity by encouraging innovation and entrepreneurial skills. From such interest, the link between entrepreneurial activity and education as an instrument to enhance entrepreneurial drive-in society has emerged (Kuratko 2005; Fayolle et al. 2019). Recent studies demonstrate the positive effect of entrepreneurship programs on students’ behavior and attitude (Adeel et al. 2023). Since the flourishing of entrepreneurship as a field of study, some researchers have focused on a particular type of entrepreneurship that finds a way to solve social problems towards the business organization (Boschee 2006). Such ventures are known as social enterprises whose intellectual foundation is in the social value creation theories. Some bibliometric studies confirm the growing interest in this specific type of entrepreneurship (Tan-Luc et al. 2022). Before that, other authors pointed out a relationship between social entrepreneurship and education that deserve to be studied (Rey-Martí et al. 2016; Carmona et al. 2018). In recent years more specific research has focused on social entrepreneurship and education, studying the content of different courses (Ndou 2021; Saebi et al. 2019). Nevertheless, a research analysis of social entrepreneurship education has not yet been conducted. As such, this study offers to respond to the existing gap.

Therefore, we present a paper structured as follows: First, we outline a summary of the most relevant research of the domains under study: Entrepreneurship Education (EE); Social Entrepreneurship (SE), and Social Entrepreneurship Education (SEE). Second, we set the objectives and the research questions. Third, we present a description of a mixed bibliometric review methodology. We continue with a fourth section showing the results of the study Afterword, a panoramic review (Oxman et al. 1994) was carried out, incorporating systematic aspects in the search and synthesis. We followed the SALSA protocol (Grant and Booth 2009), which takes its name from the four main phases of the review as follows: search, appraisal, synthesis and analysis. In turn, we followed the guidelines of Donaldson (2019), adapted to our type of research, and focused the study on the six phases of analysis. Thus, the results are discussed critically with the research questions. Finally, we conclude with some implications for practice at different levels and future lines of research.

2. Theoretical Frameworks

2.1. Entrepreneurship Education (EE)

The realm of entrepreneurial studies concerning education has been actively researched in the last 20 years (Kyrö 2015; Fayolle et al. 2019). Education is acknowledged as an external factor that can increase entrepreneurial intention and is based on intention models (Carsrud and Brännback 2011), although most articles focus on measuring the impact on higher education (Nabi et al. 2017; Adeel et al. 2023).

Foundations in human capital theories (Becker 1962) are also essential to understanding the contribution of education in fostering economic development via entrepreneurship (Unger et al. 2011). The notion of entrepreneurship in education is essential in the EE literature (Ladevéze and Núñez-Canal 2016). Consensus about EE is based on a triple perspective: education for entrepreneurship, education via entrepreneurship, and education about entrepreneurship (Gibb 2002), where having a broad sense of entrepreneurship in education is critical (Kyrö 2015). Entrepreneurship in education includes not only the venture creation process but the competence of the entrepreneurs’ motivations and aspirations (Neck and Greene 2011). The approach to entrepreneurship is also different regarding the educational stages, from an extensive meaning for primary and secondary education based on all innovative possibilities to a process approach in higher education (Welsh et al. 2016). In this sense, entrepreneurial education has been understood as a pedagogy (Jones and Iredale 2010; Hägg and Gabrielsson 2019), since creating an enterprise is a method of increasing initiative and innovation. The literature concludes that EE is a transversal and multidisciplinary domain beyond the business process that requires a holistic understanding (Fayolle 2013). Europe has followed this comprehensive approach to entrepreneurship, as well as most European countries in their internal education regulations (Bourgeois et al. 2018).

2.2. Social Entrepreneurship (SE)

Since the last century, a new figure appeared in the economic context that did not fit with the figures of NGOs or philanthropy. For these organizations, the social objective was carried out through a company with a commercial logic. These social entrepreneurs attracted the attention of some scholars, who began searching for the differences between these kinds of entrepreneurship (Boschee 2006). Since the first studies in SE, the phenomenon was framed in the theoretical tradition of entrepreneurship described by Schumpeter, but with a social mission priority (Dees 2001). Scholars refer to studies of entrepreneurship to understand the social entrepreneur’s motivations, intentions, processes, and traits (Dacin et al. 2011). Classic economics has developed the SE concept based on the theory of entrepreneurial capability in all human endeavors (Shockley and Frank 2011).

Nevertheless, some exploratory studies have identified some characteristics of such entrepreneurs (Alvord et al. 2004). Several have searched for the difference between a for-profit entrepreneur and a social entrepreneur (Boschee 2006; Shaw and Carter 2007), and others focus on studying the motivations and concerns (Álvarez de Mon et al. 2021). Some refer to the agency theory to explain the conflicts of the nature of the duality of the activity (Davis et al. 2021). The tensions lived by social entrepreneurs are also studied from the paradoxical leadership model (Smith et al. 2012).

Others refer to organization theories to consider SE as a hybrid organization (Battlilana et al. 2014). The effectuation theory has also been used to understand the process of SE creation (Yusuf and Sloan 2015) and the bricolage theory related to using resources in social venture creation (Di Domenico et al. 2010; Bacq et al. 2015). Social entrepreneurship intentions have been studied extensively in the context of self-efficacy theories. (Hockerts 2017; Tran and Von Korflesch 2016).

Finally, the literature describes SE as discovering opportunities to create social ventures and solve societal problems (Agafonow 2014; Zahra et al. 2009).

Nevertheless, SE is still a fragmented concept due to highly diverse topics and issues in the research sphere (Saebi et al. 2019; Smith et al. 2013). Therefore, creating a consensus involving the definition of the SE is problematic. Thompson et al. (2000) defined SE as a desirable option for individualistic, private projects to solve current and future challenges. Recent findings have emphasized the social mission, economic value creation, and impact maximization, looking for consensus on the definition of SE (Wu et al. 2020). Recent systematic research has linked social innovation to social entrepreneurs (Grilo and Moreira 2022). Therefore, we agree that all the literature about entrepreneurs must be helpful and that studies on SE should be put within the framework of existing theories and entrepreneurial research models, highlighting SE differences that integrate capitalist logic with social value creation (Short et al. 2009; Dacin et al. 2011).

2.3. Social Entrepreneurship Education (SEE)

Several bibliometric studies on SE indicate that education is essential (Carmona et al. 2018). In this context, education in SE is a logical evolution of the general framework of EE. Some studies have focused on SE course curriculums (Ndou 2021), discussing the pedagogical approach (Saebi et al. 2019). The students’ involvement in SE has also been studied with positive results (Hockerts 2017). The creation of social enterprises has become frequent as an innovative methodology introducing a moral and social perspective when embarking on a business project (Vázquez-Parra et al. 2022). The literature has addressed the question if SEE is a new field of study or if it is only a specification of EE theories with the conclusion that the social orientation of the entrepreneurship projects allows for considering the development of specific social skills and greater human aspirations for the students (Pache and Chowdhury 2012).

As a project-based methodology, entrepreneurial education can embrace social rather than profit goals, having a primary ethical component (Marina 2010). From this point of view, SE has become a more comprehensive tool for fostering skills and attributes of entrepreneurship values and a moral purpose in any undertaking (Smith et al. 2016). Furthermore, the implication of social change that is proactive and dynamic has become a desirable goal for education (Sen 2007). Nevertheless, a bibliometric study of the literature on SEE has yet to be carried out. As a conclusion of the literature review, this work aims to conduct an academic study to handle the following research questions:

RQ 1: What are SEE’s main characteristics and research trends in the 2000–2022 period?

RQ 2: How are the concepts of SE and education correlated?

RQ3: To what extent is SEE a specific realm of EE?

To address the task, we use a hands-on literature review on a selected number of articles from 2000 to 2022, followed by a lexicometric content analysis.

3. Material and Methods

The following section presents the methodologies combination used to answer the research questions. The main objective is to map research fields, minimize subjectivity, and improve the reliability of the results (Bernatović et al. 2022). Currently, there is a growing interest in methodologies that analyze textual statistics (Roy and Garon 2013), develop content analysis (Reinert 1990), carry out semantic analysis, and perform thematic analysis or data mining.

In the research herein, lexicometric content analysis identifies thematic units derived from the automatic extraction of hidden knowledge patterns in text data. This co-word analysis allows us to identify frequently occurring terms that indicate related concepts. The frequency of co-occurrence shows the strength of relationships between items (He 1999). This technique has been used previously on SE (Tan-Luc et al. 2022).

This research focused on the systematic review of the literature published in academic journals belonging to the Web of Science database (WOS). This database is renowned for its rigor and quality in indexing more than 171 million academic articles from over 34,000 journals in all scientific fields, including social sciences, upon which our work is based. The search was limited to articles indexed in the Web of Sciences Social Index (SSCI) and excluded articles indexed in the Science Citation Index (SCI), the Arts & Humanities Citation Index (A&HCI), and the Emerging Sources Citation Index (ESCI). The search was limited to articles indexed in the following categories: business management, and educational research. Articles indexed in categories farther away from the subject of the article, such as economics, ethics, hospitality, environment, etc., were excluded. Finally, following preceding works, the book format, book chapters, book reviews, and proceedings papers were excluded (Liñán and Fayolle 2015). Nevertheless, unlike other systematic reviews, we have not applied exclusion criteria based on the number of citations.

The search is limited to the 2000 to 2022 period, as the Lisbon European Council in 2000 year is considered as the start of entrepreneurial education expansion. As a result, 401 articles are reviewed from different fields.

The review methodology, taking into account the research questions and including two different techniques, consisted of six phases as detailed (Table 1). In addition, the search criteria followed in other reviews (Pittaway and Cope 2007) were used to identify relevant articles. Thus, the review focused on peer-reviewed, refereed scientific publications that met quality standards and had the highest impact in their field (Ordanini et al. 2008; Podsakoff et al. 2005).

Table 1.

Phases of the review process.

In the first phase, the objectives and the research question were set according to the academic literature. Secondly, a detailed examination of the publications was carried out according to “Social Entrepreneur” or “Social Entrepreneurship” and “Education”. The exclusion criteria were defined and applied to the papers in the third phase. In the next phase, a careful reading of the titles and abstracts was conducted for the classification in the 12 dimensions. Some articles that did not correspond to the subject were eliminated, resulting in a final number of 367. This pre-processing task includes units of analysis standardization, eliminating duplication, and avoiding spelling errors, ensuring the data quality (Cobo et al. 2011).

Furthermore, in the fifth phase, a lexicographic content analysis using co-occurrence grouping techniques was applied (Callon et al. 1983); this evaluation uses the most important words to establish relationships and build conceptual structures. The unit of analysis is a concept, not a document, author, or journal. Roy and Garon (2013) describe several software packages for qualitative analysis. On this occasion, we used the lexicographic analysis software Iramuteq (Interface de R pour les Analyses Multidimension-nelles de Textes ET de Questionnaires) developed by Pierre Ratinaud (Ratinaud 2009). This software was selected because it is an automatic, free, open-source program. Examining lexical profiles (both words and lexemes), it analyzes terms, identifies correlation patterns and similarities, and hierarchically groups the text’s main lexical domains to identify the narrative’s overall semantics. However, a large amount of relational information is generated. As such, it was necessary to resort to a refinement algorithm (Kamada and Kawai 1989), which has made it possible to visualize the pertinent information. Finally, this type of assessment enables the creation of textual analysis templates for text analysis, which compiles a quantitative, exhaustive description of the vocabulary and facilitates the extraction of non-explicit information within the texts (Reinert 1990).

The software Iramuteq generates approximately 800 co-occurrences; thus, lexical units are formed within a textual corpus which are also lexically close to each other among the forms they contain. The software produces an image of branches of clusters with diverse colors since they bring together a set of words related by their similarity to the object of study. The colors of the clusters are random and only serve to visualize the differentiation among common word blocks. Terms with the same color belong to the same thematic cluster. The size of the word is directly related to its frequency of use.

Consequently, the larger size reflects the higher frequency of words graphically. Likewise, link thickness shows relationship importance: the keywords are at the nodes of the graphs and represent the co-occurrences. Finally, the shorter distance between the terms indicates a relevant relationship. Iramuteq also provides descriptive statistics related to the corpus of digitized texts, such as word number and frequency, the classification of lexical units, the main lexical forms, etc. The analysis and interpretation of these data allow us to gain a more precise, deeper insight into the content of the texts and to conclude, for example, which are the main recurring themes of the texts analyzed. As a final step, we present the discussion and implications of the results of the process.

4. Results

The results are presented responding to the research questions.

RQ 1: What are SEE’s main characteristics and research trends in the 2000–2022 period?

The papers were classified according to 12 dimensions to respond to this first research question (Table 2) as follows: 1. Definition of SE; 2. Identity of the social entrepreneur (characteristics, personality traits, and skills); 3. Values and ethical features in SE; 4. SE, sustainability, and corporate social responsibility; 5. SE intentions; 6. Gender and SE; 7. Agricultural/rural and sports-related SE; 8. Social enterprises of educational activity; 9. Education and SE; 10. Innovation and SE; 11. SE and financial resources; and 12. Literature reviews on SE.

Table 2.

Relationship between the dimensions and academic literature.

There are two dominant topics: First, Dimension 9, concerning education in SE with 23% (85 articles) of the articles analyzed, and secondly, Dimension 2, concerning the Identity of the social entrepreneur with 19.6% (72 articles). The following dimensions compile the various articles and distribute them evenly at 10.3% (38 articles) for Dimension 1, Definition of SE, and 9% (33 articles) for the Dimensions of SE intention along with SE and financial. Finally, the least researched topics are Dimension 6, Gender and social entrepreneurship, and Dimension 8, Social enterprises of educational activity, at 3.5% (11 and 13 articles) of the research. Moreover, logically, the lowest scientific production corresponds to Dimension 12, known as Literature reviews on SE, at 2.7% (10 articles).

The domain 9 Education in SE is logically the most frequently found. Nevertheless, the articles included in this criteria are dispersed and fragmented, reinforcing the idea that SEE suffers from a lack of clear theorizing. There are some that study how SEE permits students to acquire the knowledge and expertise required to successfully engage in social entrepreneurial activities by allowing them to acquire the skills to be more social oriented to create hybrid organizations. Nevertheless, we still lack a clear understating of the way SEE may position differently from general EE (Pache and Chowdhury 2012). The multilogical dimension of SEE combining the commercial and social motivations can create a new space of a specification of SEE in the field of EE that has higher aspirations for the student to embrace social venture creation with a greater purpose in solving social and environmental human problems.

Regarding Dimension 2, the work carried out by Koe Hwee Nga and Shamuganathan (2010) stands out as it defines the personality traits and attitudes that foster SE competence. We concur with these authors that character development is the most appropriate philosophical–educational orientation for framing SE as an educational phenomenon insofar as it contributes to developing values, virtues, ethical reflection, conscience, and courage in students. In addition, it is important to highlight that studies about SE traits that reference the general entrepreneurship literature and are consequently applicable, such as the initiative to convert will into action, opportunities search (Shane and Venkataraman 2001), a moderate risk-taken orientation, self-confidence (Amorim Neto et al. 2018), learning from mistakes (Minniti and Bygrave 2001), and creativity (Road et al. 2017). The shaping of personal identity is a dynamic process involving character, emphasizing human openness. It leads to making decisions, as well as being responsible and consistent. It also allows for emotional balance, self-criticism, and mistakes’ acceptance. Moreover, it helps to forge autonomy as a willing quality in the operational virtues of making sound choices rationally. Thus, many of the competencies associated with SE have to do with character attributes such as perseverance, flexibility, initiative, self-confidence, self-esteem, organization, communication/negotiation, teamwork, effort/tenacity, risk-taking, tolerance of change, and fortitude against failure. In some of the studies categorized in this Dimension 2, the affective aspect and social entrepreneurs’ emotional intelligence are emphasized (Bhat 2017). How story lives, family, educational background, and experiences influence social entrepreneurs’ intentions are studied (Cohen and Katz 2016). Based on the preceding information, educators’ emotional intelligence and attention on the resolution of social problems, disabilities, social inclusion, and poverty, as elements to be taken into account for equitable, fair intervention, highlight the fundamental role of the university.

Personal autonomy is a promotor of initiative and has the capability to project and build personal identity. This aspect is linked to Dimension 3, Values and ethical features of SE. In this sense, SE is a means of learning ethics in carrying out projects (Awaysheh and Bonfiglio 2017). As the literature explains, social concerns and empathy are the main prerequisites in founding a social enterprise and an essential element in predicting its scalability and impact (Smith et al. 2016). Therefore, SEE is undoubtedly a tool for teaching ethics and the moral aspect of entrepreneurial motivation (Vázquez-Parra et al. 2022).

In terms of the type of articles published, those of an empirical nature (252) stand out (68.6%), compared to 115 (31.4%) of a theoretical nature, which indicates progress in the study of this discipline beyond conceptual articles (Short et al. 2009). The journals that have published the most articles on this issue since 2000 are the following: Journal of Social Entrepreneurship (15 articles); Social Enterprise Journal (10 articles); Sustainability (10 articles); Academy of Management Learning & Education (seven articles); Voluntas (seven articles); Entrepreneurship Research Journal (five articles); Frontiers in Psychology (five articles); Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economics (five articles); and Revesco-Revista de Estudios Cooperativos (five articles).

In summary, to respond to the first research question, we see the same fragmentation of studies as in the more generic EE field, where there is a need for consensus about the concept of SE in the educational domain. Most of the researchers come from the economic field, with less frequency from the phycology. Moreover, no representative educational journals are published about SE in education.

RQ 2: How are the concepts of social entrepreneurship and education correlated? Cluster analysis.

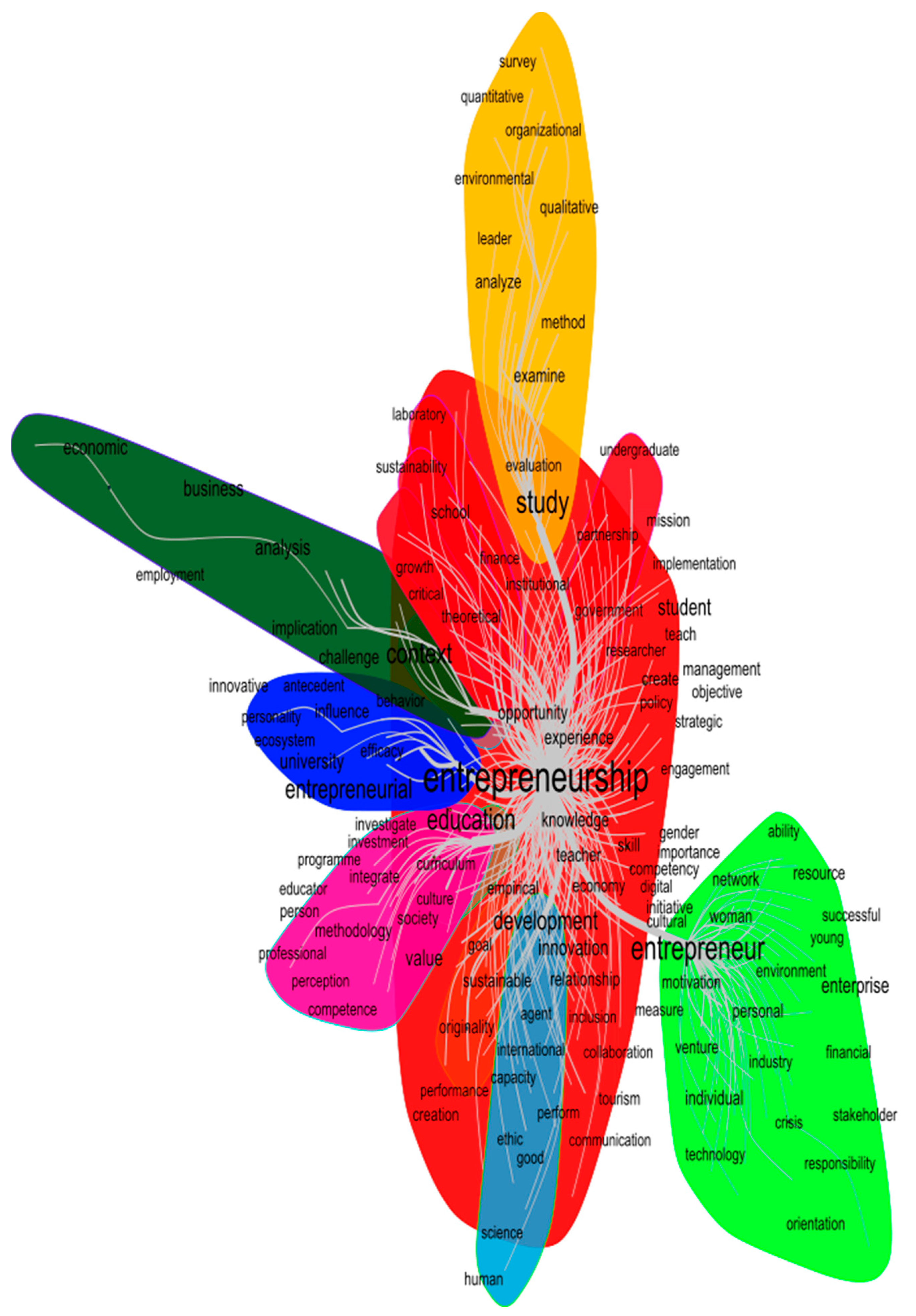

The Iramuteq software was applied to the 367 titles and abstracts of the articles reviewed. The results provide a snapshot image of the texts analyzed that allows us to interpret the relationships and suggest what is missing: it makes it possible to visualize the key words and themes that are not so obvious when reading (O’Neill et al. 2018). The Iramuteq analysis tool produced the graph shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The common co-word system generated using Iramuteq analysis software. Source: Produced by the authors of this study.

The lexicometric analysis yielded two types of results. Firstly, it made it possible to define the main research topics in the field and to classify them according to their level of development. Secondly, it enabled the keyword lists to be associated with each thematic cluster. The name of the cluster is defined by the keyword, which is the most important node.

The image shows a red-colored, central core containing the word entrepreneurship, which acts as a guide for the theme of all the articles. As mentioned above, studies on SE related to education should be part of the entrepreneurship domain as an economic phenomenon which, due to its social and welfare-producing significance, extends its interest to other social sciences, specifically to education. Six main research themes have emerged from the broad concept of entrepreneurship. These six clusters are named as the main word node: entrepreneur, development and innovation, social entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial university, context, and types of studies in social entrepreneurship (Table 3). Moreover, the cluster are related to the literature dimensions discussed in the previous section.

Table 3.

Main groups of co-words identified via clustering analysis and related to the domain’s categorization.

Main groups of co-words identified via clustering analysis and related to the domains categorization.

Entrepreneur: The term entrepreneur, represented by the green cluster, has almost no points where it intersects with the other clusters. The approach to study the individual who is a social entrepreneur is one of largest number of articles topics, as was pointed out in the previous section. In the recent years, despite significant development, there is still no clear agreement on its definition (Bacq and Janssen 2011). The search for a consensus on a definition of SE is the subject of systematic reviews that seek to gather all the perspectives and nuances to define the term (Wu et al. 2020). Short et al. (2009) pointed out that even though the academic production on SE of a theoretical nature (Popoviciu and Popoviciu 2011) exceeds empirical studies (Carraher et al. 2016), scarce progress has been made in defining the term, despite the fact of being a promising global phenomenon, yet there has been scant academic research of a rigorous nature. Interest in clarifying the concept has led Choi and Majumdar (2014) to compile the different definitions and visions of social entrepreneurship, as well as the different schools of thought by which it can be identified. More recently, Saebi et al. (2019) pointed out that most definitions agree on the primacy of social over economic value as the social entrepreneur objective. It is important to maintain the effort to find a clear definition of SE due to the consequence of incorporating SE into education (Solomon et al. 2019). However, this has led to neglect in other areas, such as market focus and innovation. This area also includes several studies that focus on the personal profile of social entrepreneurs (Hockerts 2017), in addition to interest in matters such as gender, with a preference for female social entrepreneurs (Dickel and Eckardt 2021) as well as those who are young (Lewis 2016). This cluster is related to development and innovation.

Development and Innovation: Represented by the light blue cluster in the low-central position, which is an important location. The concepts most strongly related to the development and innovation block, and to the constructs of entrepreneur and education, are the following: sustainability, capacity, ethics, relationship, international, participant, inclusion, originality, good, agent, and human. These concepts are included in the different articles (Table 1) within Dimension 10, Innovation and social entrepreneurship. In this regard, SE accepts the implementation of innovative strategies to provide a solution to society, not only economical, but mainly of a moral, social, and cultural nature (Newth 2016). As such, the social entrepreneur becomes an agent of change (agency theory) who takes on new challenges and responsibilities for the social good (Davis et al. 2021). This conclusion highlights the ethical vision of innovation in SE (Toledano 2020), as well as the need to train social entrepreneurs with certain personal and professional qualities: creativity, innovation, capacity for reflection, and an ethical vision.

Another aspect of the research analysis revolves around the relationship between SE and sustainability (Zhu et al. 2016). SE, and entrepreneurship in general, have a direct relationship with the sustainability objectives that are now highly relevant in the business world (Méndez-Picazo et al. 2021). It advocates an education that promotes sustainable innovation to address social, environmental, and human development challenges. Companies are considered change agents in their role to implement original social impact solutions. They have assumed a new position beyond traditional economics, which is a business role concerning the shared value of Porter and Kramer (2011). Finally, the great challenge of SE and innovation is to address any neglected needs in order to respond to the problems of vulnerable people. Future social entrepreneurs must correctly understand this aim as some literature highlights the disengagement of social entrepreneurs with moral behaviors to justify helping others (Muldoon et al. 2022). This is a key issue that reinforces the use of SEE projects as an innovative tool to teach ethics in action. The work of inclusion (De Ruysscher et al. 2017), which involves the empowerment of disadvantaged collectives (Wu et al. 2019) in order for them to lead a dignified human life, is one of the motivations of today’s social entrepreneurs.

Education: To begin with, the cluster known as education, represented by the pink color, combines the concepts of entrepreneurship and education with various related concepts. First, we have observed words referring to educational elements such as curriculum, program, and methodology. These studies investigate the generation of educational frameworks related to SEE. Since the first courses at Harvard University in the early 1990s, many educational programs have taught entrepreneurship with a social purpose. In such research, we find studies that try to explain different educational models in SE (Miller et al. 2012). These studies are based on the EE theoretical framework of teaching for SE and about entrepreneurship (Gibb 2002). On the other hand, the bond with the words pedagogy and strategy shows the authors’ interest in studying the instrumental character of these education models as pedagogy (Jones and Iredale 2010). These studies aim to develop SE competence (Miller et al. 2012) and test individual impact and effectiveness (Smith et al. 2012). The relationship between SEE and active methodologies has been observed as a strong research trend, following the general lines of entrepreneurial education (Hytti and O’Gorman 2004). Some research has studied the methodological component of this educational phenomenon as experiential learning or learning by doing (Chang et al. 2014). This is consistent with the trend in SE toward active, engaged learning from which new concepts are emerging in the wake of the changemaker movements (Sen 2007).

Furthermore, the word value stands out, suggesting that this cluster joins educational studies linked to education in values with the importance of morality and ethics in entrepreneurship competence (Marina 2010). Ever since the first studies on social entrepreneurship, the importance of ethical motivation in the characteristics of social entrepreneurs has been confirmed (Mort et al. 2003). As mentioned above, this allows us to perceive that education in personality has a link to education in SE (Vázquez-Parra et al. 2022). This trend is also reflected in recent studies linking this type of entrepreneurship with values such as compassion (Miller et al. 2012). Finally, the word society reflects how many studies that investigate entrepreneurial education programs aim to raise awareness and develop projects that solve current problems in our society (Swanson and Di Zhang 2010).

Entrepreneurial university: The cluster represented by the dark blue bubble highlights the adjective entrepreneurial with the noun university, which confirms the large number of studies at the higher education level. Social enterprises have become a suitable methodological instrument in management education (Awaysheh and Bonfiglio 2017). The concept of entrepreneurial university is largely studied in the literature (Forliano et al. 2021) and is identified to be a great trend. A new role of universities is confirmed as entrepreneurial organizations that goes beyond teaching and research plays an active influence in the socioeconomic development of the communities where they operate (García-Hurtado et al. 2022).

On the other hand, in this cluster, we find words such as behavior, personality, influence, antecedent, and perception reflecting a general trend in the literature to look for the extent to which education influences the development of students’ entrepreneurial competence (Koe Hwee Nga and Shamuganathan 2010; Hockerts 2018). This line of thought follows a literature trajectory that considers higher education to be a determining factor in shaping entrepreneurial intention (Carsrud and Brännback 2011).

Context: In forest green, the context cluster is connected to that of entrepreneurship via a very clear node. In this group of words, we can see a dispersion of concepts that correspond to business-related terms such as economic, employment, and business model. This cluster reflects the importance being given to the phenomenon of SE in management and economics fields. The study of SE is a unique opportunity to question and reformulate some assumptions in the field of business and management (Mair and Martí 2006). On the other hand, these papers refer to the group of articles that follow a line of research on the exogenous factors of entrepreneurship and refer to how entrepreneurial ecosystems can influence the founding and operation of their ventures (Roundy 2017). This trend is part of the general line of study on the adequacy of political and institutional environments in the development of projects related to entrepreneurship (Estrin et al. 2013).

Types of Studies: Represented by the yellow color, these terms have a low level of association. Related concepts are as follows: method, quantitative, qualitative, theoretical, research, analyze, examine, and evaluation. The methodology of the articles analyzed is mainly quantitative (252), compared to 115 qualitative articles. In most of the research, there is a trend toward analyzing and examining the impact of social entrepreneurs on different areas of society such as the following: tourism, agriculture, sport, health, rural areas, politics, etc. Finally, other types of studies we have encountered in this cluster are bibliographic reviews, which help to present a map of the most relevant research in certain fields of study.

RQ3: To what extent is Social Entrepreneurship Education (SEE) a specific realm of Entrepreneurship education?

The increasing scientific production, the number of specialized journals, the diversity of authors, and the working disciplines corroborate that SEE articles focus on various issues and complex realities. Furthermore, a shift in the direction of research on EE is perceived as a more social and moral approach to entrepreneurial learning when studying social entrepreneurship in education. The SEE research has a perspective that includes ethics, human values, empathy approach, emotional attributes, sustainability interests, environmental awareness, inclusion, diversity, and social wellbeing in the entrepreneurs’ motivation. Therefore, SEE pattern trends show rising interest in promoting an entrepreneurial spirit that combines market logic and efficiency with human values and action-oriented awareness of social and environmental problem-solving activities.

Since the incorporation of EE at primary levels, it has been frequently criticized in the educational sphere because of the market orientation implication of all issues of society as health, education, etc. Nevertheless, the literature about EE has already solved these concerns with different arguments. Its effectiveness of a narrow sense of entrepreneurship is questioned (Gibb 2002); the educational value of developing a business plan is discussed (Jones and Penaluna 2013); and the holistic concept of entrepreneurial behavior is confirmed (Kyrö 2015). As such, we can consider a consensus about using a broad notion of entrepreneurship (Ladevéze and Núñez-Canal 2016), especially in the first years of education. Furthermore, the literature on EE integrates in the entrepreneurship competence the entrepreneurs’ motivations and their aspirations (Neck and Greene 2011). In this sense, competence aims to develop among students’ autonomy, personal initiative, critical spirit, autonomous thinking, creativity, reflection, decision making, and problem solving. The SEE literature broadens the focus of entrepreneurial competence to a more philosophical aspect that was used so far in conventional studies on entrepreneurial education (Azqueta and Sanz-Ponce 2021). As such, it includes an ethical and sustainable vision, which has a direct impact on society.

The teaching methodologies necessary for acquiring social entrepreneurial competence must develop a positive feeling for SE (Steiner et al. 2018). Following the theories of EE as a pedagogy (Kyrö 2015), SEE places the student at the center of the process and provides him/her with autonomy and responsibility and favors active and experiential learning (Hockerts 2018). Therefore, a multidimensional concept of SEE is required (Vázquez-Parra et al. 2022), which stimulates innovative projects in classrooms that engage students emotionally in their role as changemakers for a better society and better world, generating a context for social awareness and active citizenship.

Incorporating social entrepreneurship in education is related to the pedagogies of social value creation (Lackéus 2020). This value is created for others and related to the 4Cs—conceive, create, capture, and critique (Jones et al. 2021). This approach has its educational and historical roots in the works of educational philosophers such as Dewey, Makiguchi, and Whitehead (Gebert and Joffee 2007). In this light, students not only solve a social need, but it has other benefits because it contributes to the personal development of individuals, where students gain an enriching personal learning experience.

Consequently, the most appropriate response to RQ3 is that education for SE can become a specific area of EE, raising students’ awareness about projects to solve social and environmental problems beyond seeking business opportunities. The distinguishing factors of this kind of EE are to generate initiatives with ethical values, emotional involvement, and a positive impact on society as a whole concerning environment, fair trade, health, and human rights (Portales 2019), with sustainable solutions (Shu et al. 2020). Moreover, incorporating social projects in primary education as an innovative methodology is coherent with the theoretical frameworks of an extended concept of entrepreneurship in education and it mitigates the criticism. Furthermore, SEE values the person’s social dimension, increasing intrinsic student satisfaction and improving learning outcomes. It develops a holistic approach that strengthens the links between business and EE and social needs and citizenship.

Finally, concerning the gaps in research on SEE, it is still necessary to clarify the SE concept as an educational phenomenon based on the rigorous EE literature already consolidated as a field of study in the last decades. Such clarification is not new in EE, as was already pointed out (Fayolle 2013). The delimitation of the subject is essential to foster efficient economic and educational policies. The introduction of SE enlarges the debate on what entrepreneurship is in the educational system as a goal. A wide range of topics continue to offer opportunities for specificity and academic agreement on their relationships and implications.

5. Conclusions and Limitations

This study combines bibliometric study with lexicometric analysis to capture the research activity in SEE in the last decades. The study’s results try to answer three research questions posed following the literature. Then, some recommendations are presented to help improve academic research in SEE.

Firstly, the results propose to solve the ontological and epistemological challenge of the concept of SEE. This implies the need for a holistic, unified, and interdisciplinary approach to entrepreneurship in education, highlighting the social impact goals of the projects. This distinguishing perspective is still minimally explored in academic research. Incorporating SE in education provides a motivating learning experience that contributes to the personal development of students’ capabilities. The development of hybrid methodologies that combine experiential learning and active and agile methodologies are outlined as future lines of work. Introducing a specific concept of a social entrepreneur with the specifics characteristics (emotional aspects, social aspirations, empathy for others, environmental awareness, human rights, etc.) can contribute to training young people as agents of change who will have to successfully and ethically solve tomorrow’s problems.

Secondly, SEE is still a fragmented field with dispersed studies. Therefore, it is necessary to claim more rigorous academic research based on previous theoretical frameworks already developed by the solid EE literature. Some neglected lines of work within this field of study are also pointed out. It seems necessary to specify a framework of SE competence within the already developed EE models. Therefore, we propose that SE competence integrates the attributes, skills, and knowledge about entrepreneurship with a priority focus on the personal development elements regarding ethics and social impact. This proposal is founded for SE and about SEE theories using SEE projects as an innovative tool to teach ethics in action.

Although the notion of SE is still unclear in the educational context, we suggest addressing this problem with academic rigor based on an already solid framework for a broader concept of the entrepreneurship term in education.

The conclusions have future implications at three levels: (a) at an educational policy level, promoting a specific SE competence based on the ethical construction of personality, especially in primary education. (b) At the university level, encouraging transversal courses and competences for projects linked to social development goals and explicit social value creation; (c) at an economic policy level, promoting entrepreneurial policies whose main objective is to promote citizen participation in social innovation.

In summary, this work supports future research on a specialization realm of EE with the need for further research on SEE. Potential lines of research revolve around the relationship between SEE, sustainability, innovation, and the new role of businesses in measuring social impact. A growing field of study is the role of informal education. Finally, the SE mission suits better with a moral and educational purpose. The need for a consensus about moral educational goals is another line of investigation for our educational systems. Concerns about poverty, social inclusion, and disability have appeared as emerging issues for social entrepreneurs and education. One limitation of this research is the absence of a search for articles in databases other than the Web of Science. Research published in books or book chapters was not taken into account either. Extending the search to other databases and other formats such as books or book chapters could show a different picture of the problems studied.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.N.-C., R.S.-P. and A.A.; methodology, M.N.-C., R.S.-P. and A.A.; formal analysis, M.N.-C., R.S.-P. and A.A.; investigation, M.N.-C., R.S.-P. and A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.N.-C., R.S.-P. and A.A.; writing—review and editing, M.N.-C., R.S.-P. and A.A.; funding acquisition, M.N.-C., R.S.-P. and A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by MCIN I+D+i PID2019-104408GB-I00, grant number MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and the APC was funded by 30.250€.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of UNIVERSIDAD DE SEVILLA (protocol code ABG21 and date of approval 7 April 2021) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adeel, Shahzada, Ana Dias Daniel, and Anabela Botelho. 2023. The effect of entrepreneurship education on the determinants of entrepreneurial behaviour among higher education students: A multi-group analysis. Journal of Innovation, and Knowledge 8: 100324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agafonow, Alejandro. 2014. Toward A Positive Theory of Social Entrepreneurship. On Maximizing Versus Satisficing Value Capture. Journal of Business Ethics 125: 709–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvord, Sarah H., L. David Brown, and Christine W. Letts. 2004. Social Entrepreneurship and Societal Transformation: An Exploratory Study. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 40: 260–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim Neto, Roque do Carmo, Vinicius P. Rodrigues, Douglas Stewart, Anna Xiao, and Jenna Snyder. 2018. The influence of self-efficacy on entrepreneurial behavior among K-12 teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education 72: 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awaysheh, Amrou, and Drew Bonfiglio. 2017. Leveraging experiential learning to incorporate social entrepreneurship in MBA programs: A case study. International Journal of Management Education 15: 332–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azqueta, Arantxa, and Roberto Sanz-Ponce. 2021. Educación emprendedora y filosofía de la educación. Cuestiones Pedagógicas 30: 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez de Mon, Ignacio, Patricia Gabaldón, and Margarita Nuñez-Canal. 2021. Social entrepreneurs: Making sense of tensions through the application of alternative strategies of hybrid organizations. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 18: 975–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacq, Sophie, and Frank Janssen. 2011. The multiple faces of social entrepreneurship: A review of definitional issues based on geographical and thematic criteria. Entrepreneurship, and Regional Development 23: 373–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacq, Sophie, Laurel F. Ofstein, Jill R. Kickul, and Lisa K. Gundry. 2015. Bricolage in Social Entrepreneurship. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation 16: 283–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, Tae J., Shanshan Qian, Chao Miao, and James O. Fiet. 2014. The Relationship between Entrepreneurship Education and Entrepreneurial Intentions: A Meta–Analytic Review. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 38: 217–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battlilana, Julie, Metin Sengul, Anne C. Pache, and Jacob Model. 2014. Harnessing Productive Tensions in Hybrid Organizations: The Case of Work Integration Social Enterprises. Academy of Management 58: 1658–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, Gary S. 1962. Investment in Human Capital: A Theoretical Analysis. Journal of Political Economy 70: 9–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernatović, Ivija, Alenka Slavec Gomezel, and Matej Černe. 2022. Mapping the knowledge-hiding field and its future prospects: A bibliometric co-citation, co-word, and coupling analysis. Knowledge Management Research, and Practice 20: 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, Anil K. 2017. The role of emotional intelligence and self-efficacy on social entrepreneurial attitudes and social entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 8: 165–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschee, Jerr. 2006. Social entrepreneurship: The promise and the perils. In Social Entrepreneurship: New Models of Sustainable Social Change. Edited by Alex Nicholls. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 356–90. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeois, Ania, Michele Zagordo, and Aude Antoine. 2018. Entrepreneurship Education at School in Europe: Eurydice Report. Brussels: Publications Office. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2797/301610 (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Callon, Michel, Jean P. Courtial, Willian A. Turner, and Serge Bauin. 1983. From translations to problematic networks: An introduction to co-word analysis. Social Science Information 22: 191–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, Viviane C., Cristina D. Martens, Ana Carneiro Leão, Jorge Nassif, and Henrique de Freitas. 2018. Social entrepreneurship: A bibliometric approach in the administration and business field. Estudios Gerenciales 34: 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraher, Shawn M., Dianne H. Welsh, and Andrew Svilokos. 2016. Validation of a measure of social entrepreneurship. European Journal of International Management 10: 386–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carree, Martin, André Van Stel, Roy Thurik, and Sander Wennekers. 2002. Economic development and business ownership: An analysis using data of 23 OECD countries in the period 1976–1996. Small Business Economics 19: 271–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carsrud, Alan, and Malin Brännback. 2011. Entrepreneurial Motivations: What Do We Still Need to Know? Journal of Small Business Management 49: 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Jane, Abdelhafid Benamraoui, and Alison Rieple. 2014. Learning-by-doing as an approach to teaching social entrepreneurship. Innovations in Education and Teaching International 51: 459–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Nia, and Satyajit Majumdar. 2014. Social entrepreneurship as an essentially contested concept: Opening a new avenue for systematic future research. Journal of Business Venturing 29: 363–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, Manuel J., Antonio G. López-Herrera, Enrique Herrera-Viedma, and Francisco Herrera. 2011. Science mapping software tools: Review, analysis, and cooperative study among tools. Journal of the American Society for information Science and Technology 62: 1382–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Hila, and Hagai Katz. 2016. Social entrepreneurs narrating their careers: A psychodynamic-existential perspective. Australian Journal of Career Development 25: 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacin, M. Tina, Peter A. Dacin, and Paul Tracey. 2011. Social entrepreneurship: A critique and future directions. Organization Science 5: 1203–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Philip E., Joshua S. Bendickson, Jeffrey Muldoon, and Willian C. McDowell. 2021. Agency theory utility and social entrepreneurship: Issues of identity and role conflict. Review of Managerial Science 15: 2299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ruysscher, Clara, Claudia Claes, Tim Lee, Fenming Cui, Jos Van Loon, Jessica De Maeyer, and Robert Schaloc. 2017. A Systems Approach to Social Entrepreneurship. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 28: 2530–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dees, J. Gregory. 2001. The Meaning of “Social Entrepreneurship”. Durham: Duke Faqua Center. [Google Scholar]

- Di Domenico, Maria L., Helen Haugh, and Paul Tracey. 2010. Social bricolage: Theorizing social value creation in social enterprises. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice 34: 681–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, Claudia, Ricardo Gouveia Rodrigues, and João J. Ferreira. 2019. What’s new in the research on agricultural entrepreneurship? Journal of Rural Studies 65: 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickel, Petra, and Gordon Eckardt. 2021. Who wants to be a social entrepreneur? The role of gender and sustainability orientation. Journal of Small Business Management 59: 196–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-García, Maria Cristrina, and Juan Jiménez-Moreno. 2010. Entrepreneurial intention: The role of gender. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 6: 261–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, Colin. 2019. Intentions resurrected: A systematic review of entrepreneurial intention research from 2014 to 2018 and future research agenda. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 15: 953–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrin, Saul, Julia Korosteleva, and Tomasz Mickiewicz. 2013. Which institutions encourage entrepreneurial growth aspirations? Journal of Business Venturing 28: 564–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, Alain. 2013. Personal views on the future of entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 25: 692–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, Alain, Dafna Kariv, and Harry Matlay. 2019. The Role and Impact of Entrepreneurship Education. London: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forliano, Canio, Paola De Bernardi, and Dorra Yahiaoui. 2021. Entrepreneurial universities: A bibliometric analysis within the business and management domains. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 165: 120522–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Hurtado, Dayanis, Carlos Devece, Pablo E. Zegarra-Saldaña, and Mario Crisanto-Pantoja. 2022. Ambidexterity in entrepreneurial universities and performance measurement systems. A literature review. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 1: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebert, Andrew, and Monte Joffee. 2007. Value creation as the aim of education: Tsunesaburo Makiguchi and Soka education. Ethical Visions of Education: Philosophies in Practice 1: 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Gibb, Allan. 2002. In pursuit of a new “enterprise” and “entrepreneurship” paradigm for learning: Creative destruction, new values, new ways of doing things and new combinations of knowledge. International Journal of Management Reviews 4: 233–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. 2009. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal 26: 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilo, Ricardo, and António C. Moreira. 2022. The social as the heart of social innovation and social entrepreneurship: An emerging area or an old crossroads? International Journal of Innovation Studies 6: 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hägg, Gustav, and Jonas Gabrielsson. 2019. A systematic literature review of the evolution of pedagogy in entrepreneurial education research. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research 26: 829–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Qin. 1999. Knowledge Discovery Through Co-Word Analysis. Library Trends 48: 133–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hockerts, Kai. 2017. Determinants of Social Entrepreneurial Intentions. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice 41: 105–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockerts, Kai. 2018. The Effect of Experiential Social Entrepreneurship Education on Intention Formation in Students. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 9: 234–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hytti, Ulla, and Colm O’Gorman. 2004. What is “enterprise education”? An analysis of the objectives and methods of enterprise education programmes in four European countries. Education Training 46: 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Brian, and Norma Iredale. 2010. Enterprise education as pedagogy. Education Training 52: 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Colin, and Andy Penaluna. 2013. Moving beyond the business plan in enterprise education. Education Training 55: 804–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Colin, Kathryn Penaluna, and Andy Penaluna. 2021. Value creation in entrepreneurial education: Towards a unified approach. Education Training 63: 101–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamada, Tomihisa, and Satoru Kawai. 1989. An agorithm for drawing general undirected graphs. Information Pocessing Letters 31: 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koe Hwee Nga, Joyce, and Gomathi Shamuganathan. 2010. The influence of personality traits and demographic factors on social entrepreneurship start up intentions. Journal of Business Ethics 95: 259–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, Norris, and Alan Carsrud. 1993. Entrepreneurial intentions: Applying the theory of planned behaviour. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 5: 315–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuratko, Donald. F. 2005. The Emergence of Entrepreneurship Education: Development, Trends, and Challenges. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 29: 577–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyrö, Paula. 2015. The conceptual contribution of education to research on entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 27: 599–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackéus, Martin. 2020. Comparing the impact of three different experiential approaches to entrepreneurship in education. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior, and Research 26: 937–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladevéze, Luis, and Margarita Núñez-Canal. 2016. Noción de emprendimiento para una formación escolar en competencia emprendedora. Revista Latina de Comunicacion Social 71: 1068–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Loarne-Lemaire, Severine, Adnane Maalaoui, and Léo Paul Dana. 2017. Social entrepreneurship, age and gender: Toward a model of social involvement in entrepreneurship. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business 31: 363–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Kate V. 2016. Identity capital: An exploration in the context of youth social entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 28: 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, Francisco, and Alain Fayolle. 2015. A systematic literature review on entrepreneurial intentions: Citation, thematic analyses, and research agenda. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 11: 907–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, Johanna, and Ignasi Martí. 2006. Social entrepreneurship research: A source of explanation, prediction, and delight. Journal of World Business 41: 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marina, José. Antonio. 2010. La competencia de emprender. Revista de Educacion 351: 49–71. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez-Picazo, María Teresa, Miguel Angel Galindo-Martín, and María Soledad Castaño-Martínez. 2021. Effects of sociocultural and economic factors on social entrepreneurship and sustainable development. Journal of Innovation, and Knowledge 6: 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Toyah L., Matthew G. Grimes, Jeffery S. McMullen, and Timothy J. Vogus. 2012. Venturing for Others with Heart and Head: How Compassion Encourages Social Entrepreneurship. Academy of Management 37: 616–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minniti, Mary, and William Bygrave. 2001. A Dynamic Model of Entrepreneurial Learning. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 25: 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mort, Gillian Maree Sullivan, Jay Weerawardena, and Kashonia Carnegie. 2003. Social entrepreneurship: Towards conceptualization. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 8: 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muldoon, Jeffrey, Pilliph E. Davis, Joshua S. Bendickson, William C. McDowell, and Eric W. Liguori. 2022. Paved with good intentions: Moral disengagement and social entrepreneurship. Journal of Innovation, and Knowledge 7: 100237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, Ghulam, Francisco Liñán, Alain Fayolle, Norrys Krueger, and Andreas Walmsley. 2017. The impact of entrepreneurship education in higher education: A systematic review and research agenda. Academy of Management Learning and Education 16: 277–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandan, Monica, Manuel London, and Tricia Bent-Goodley. 2015. Social workers as social change agents: Social innovation, social intrapreneurship, and social entrepreneurship. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership, and Governance 39: 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndou, Valentina. 2021. Social entrepreneurship education: A combination of knowledge exploitation and exploration processes. Administrative Science 11: 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neck, Heidi M., and Patricia G. Greene. 2011. Entrepreneurship Education: Known Worlds and New Frontiers. Journal of Small Business Management 49: 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newth, Jamie. 2016. Social Enterprise Innovation in Context: Stakeholder Influence through Contestation. Entrepreneurship Research Journal 6: 369–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, Maureen M., Sarah R. Booth, and Janeen T. Lamb. 2018. Using NVivo™ for Literature Reviews: The Eight Step Pedagogy (N7+1). The Qualitative Report 23: 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordanini, Andrea, Gaia Rubera, and Robert De Fillippi. 2008. The many moods of inter-organizational imitation. A critical review. International Journal of Management Reviews 10: 375–98. [Google Scholar]

- Oxman, Andrew D., Deborah J. Cook, and Gordon H. Guyatt. 1994. Users’guides to the medical literature. VI. How to use an overview. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA 272: 1367–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pache, Anne Claire, and Imram Chowdhury. 2012. Social entrepreneurs as institutionally embedded entrepreneurs: Toward a new model of social entrepreneurship education. Academy of Management Learning and Education 11: 494–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittaway, Luke, and Jackson Cope. 2007. Entrepreneurship education: A systematic review of the evidence. International Small Business Journal 25: 479–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, Philip, Scott Mac Kenzie, Daniel Bachrach, and Nathan Podsakoff. 2005. The influence of management journals in the 1980s and 1990s. Strategic Management Journal 26: 473–88. [Google Scholar]

- Popoviciu, Ioan, and Salomea A. Popoviciu. 2011. Social entrepreneurship, social enterprise and the principles of a community of practice. Revista de cercetare si interventie sociala 33: 44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Portales, Luis. 2019. Social innovation: Origins, definitions, and main elements. In Social Innovation and Social Entrepreneurship. Edited by Luis Portales. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, Michael, and Mark Kramer. 2011. Creating Shared Value. Harvard Business Review 89: 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Ratinaud, Pierre. 2009. IRaMuTeQ: Interface de R pour les Analyses Multidimensionnelles de Textes et de Questionnaires. Available online: https://cutt.ly/4LIyWxD (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Reinert, Max. 1990. Alceste: Une méthodologie d’analyse des donne textuelles et une application: Aurélia de G. de Nerval. Bulletin de Méthodologie Sociologique 26: 24–54. [Google Scholar]

- Rey-Martí, Andrea, Domingo Ribeiro-Soriano, and Daniel Palacios-Marqués. 2016. A bibliometric analysis of social entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Research 69: 1651–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribes-Giner, Gabriela, Ismael Moya-Clemente, Roberto Cervelló-Royo, and María Rosario Perello-Marin. 2018. Domestic economic and social conditions empowering female entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Research 89: 182–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Road, S., U. Kingdom, E. Bour, P. Altass, S. Wiebe, K. Lee, and R. Wattenhofer. 2017. The future of human creative knowledge work within the digital economy. Futures 105: 143–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roundy, Philip T. 2017. Social Entrepreneurship and Entrepreneurial Ecosystems: Complementary or Disjointed Phenomena? International Journal of Social Economics 44: 1252–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, Normand, and Roseline Garon. 2013. Étude comparative des logiciels d’aide à l’analyse de données qualitatives: De l’approche automatique à l’approche manuelle. Recherches Qualitatives 32: 154–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saebi, Tina, Nicolai J. Foss, and Stefan Linder. 2019. Social entrepreneurship research: Past achievements and future promises. Journal of Management 45: 70–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, Pritha. 2007. Ashoka’s big idea: Transforming the world through social entrepreneurship. Futures 39: 534–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, Scott, and Shankar Venkataraman. 2001. Entrepreneurship As a Field of Research: A Response to Zahra and Dess, Singh, and Erikson. Academy of Management Review 26: 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, Eleanor, and Sara Carter. 2007. Social entrepreneurship: Theoretical antecedents and empirical analysis of entrepreneurial processes and outcomes. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 14: 418–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shockley, Gordon E., and Peter M. Frank. 2011. Schumpeter, Kirzner, and the Field of Social Entrepreneurship. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 2: 6–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, Jeremy C., Tood W. Moss, and G. Tom Lumpkin. 2009. Research in social entrepreneurship: Past contributions and future opportunities. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 3: 161–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Yu, Ho Shin-Jia, and Tien-Chi Huang. 2020. The development of a sustainability-oriented creativity, innovation, and entrepreneurship education framework: A prospective study. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, Brett R., Geoffrey M. Kistruck, and Benedetto Cannatelli. 2016. The Impact of Moral Intensity and Desire for Control on Scaling Decisions in Social Entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Ethics 133: 677–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Wendy K., Marya L. Besharov, Anke K. Wessels, and Michael Chertok. 2012. A Paradoxical Leadership Model for Social Entrepreneurs: Challenges, Leadership Skills, and Pedagogical Tools for Managing Social and Commercial Demands. Academy of Management Learning, and Education 11: 463–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Wendy K., Michael Gonin, and Marya L. Besharov. 2013. Managing Social-Business Tensions: A Review and Research Agenda for Social Enterprise. Business Ethics Quarterly 23: 407–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, Georges Thomas, Nawaf Alabduljader, and Ramani S. Ramani. 2019. Knowledge management and social entrepreneurship education: Lessons learned from an exploratory two country study. Journal of Knowledge Management 23: 1984–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, Susan, Debbi Brock, Thomas Pittz, and Eric Liguori. 2018. Multidisciplinary involvement in social entrepreneurship education: A uniquely threaded ecosystem. Journal of ethics and Entrepreneurship 8: 73–91. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, Lee A., and David Di Zhang. 2010. The social entrepreneurship zone. Journal of Nonprofit and Public Sector Marketing 22: 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan-Luc, Phan, Pham Xuan-Lan, Angelina Nhat-Hanh-Le, and Bui Thanh-Trang. 2022. A Co-Citation and Co-Word Analysis of Social Entrepreneurship Research. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 13: 324–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, Wendy, and Lydia Bals. 2018. Achieving shared triple bottom line (TBL) value creation: Toward a social resource-based view (SRBV) of the firm. Journal of Business Ethics 152: 803–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiru, Yaso. 2011. Social Enterprise Education: New Economics or a Platypus? Online Emerald. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Jhon, Geoff Alvy, and Ann Lees. 2000. Social entrepreneurship—A new look at the people and the potential. Management Decision 38: 328–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, Preeti, Anil K. Bhat, and Jyoti Tikoria. 2017. An empirical analysis of the factors affecting social entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research 7: 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledano, Nuria. 2020. Promoting Ethical Reflection in the Teaching of Social Entrepreneurship: A Proposal Using Religious Parables. Journal of Business Ethics 164: 115–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Ann T. P., and Harald Von Korflesch. 2016. A conceptual model of social entrepreneurial intention based on the social cognitive career theory. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship 10: 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, Jens M., Andreas Rauch, Michael Frese, and Nina Rosenbusch. 2011. Human capital and entrepreneurial success: A meta-analytical review. Journal of Business Venturing 26: 341–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Parra, José C., Abel García-González, and Maria Soledad Ramírez-Montoya. 2022. Ethical education and its impact on the perceived development of social entrepreneurship competency. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning 12: 369–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, Dianne H. B., William L. Tullar, and Hamid Nemati. 2016. Entrepreneurship education: Process, method, or both? Journal of Innovation & Knowledge 1: 125–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Wen-Hsiung, Hao-Yun Kao, Shen-Hsiu Wu, and Chunh-Wang Wei. 2019. Development and Evaluation of Affective Domain Using Student’s Feedback in Entrepreneurial Massive Open Online Courses. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Yenchun Jim, Tienhua Wu, and Jeremiah Sharpe. 2020. Consensus on the definition of social entrepreneurship: A concent analysis approach. Management Decision 58: 2593–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, Juita-Elena, and Margaret F. Sloan. 2015. Effectual Processes in Nonprofit Start-Ups and Social Entrepreneurship: An Illustrated Discussion of a Novel Decision-Making Approach. American Review of Public Administration 45: 417–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, Shaker A., Eric Gedajlovic, Donald O. Neubaum, and Joel M. Shulman. 2009. A typology of social entrepreneurs: Motives, search processes and ethical challenges. Journal of Business Venturing 24: 519–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Yunxia, David Rooney, and Nelson Phillips. 2016. Practice-Based Wisdom Theory for Integrating Institutional Logics: A New Model for Social Entrepreneurship Learning and Education. Academy of Management Learning, and Education 15: 607–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).