Improving Strategic Planning: The Crucial Role of Enhancing Relationships between Management Levels

Abstract

:1. Introduction

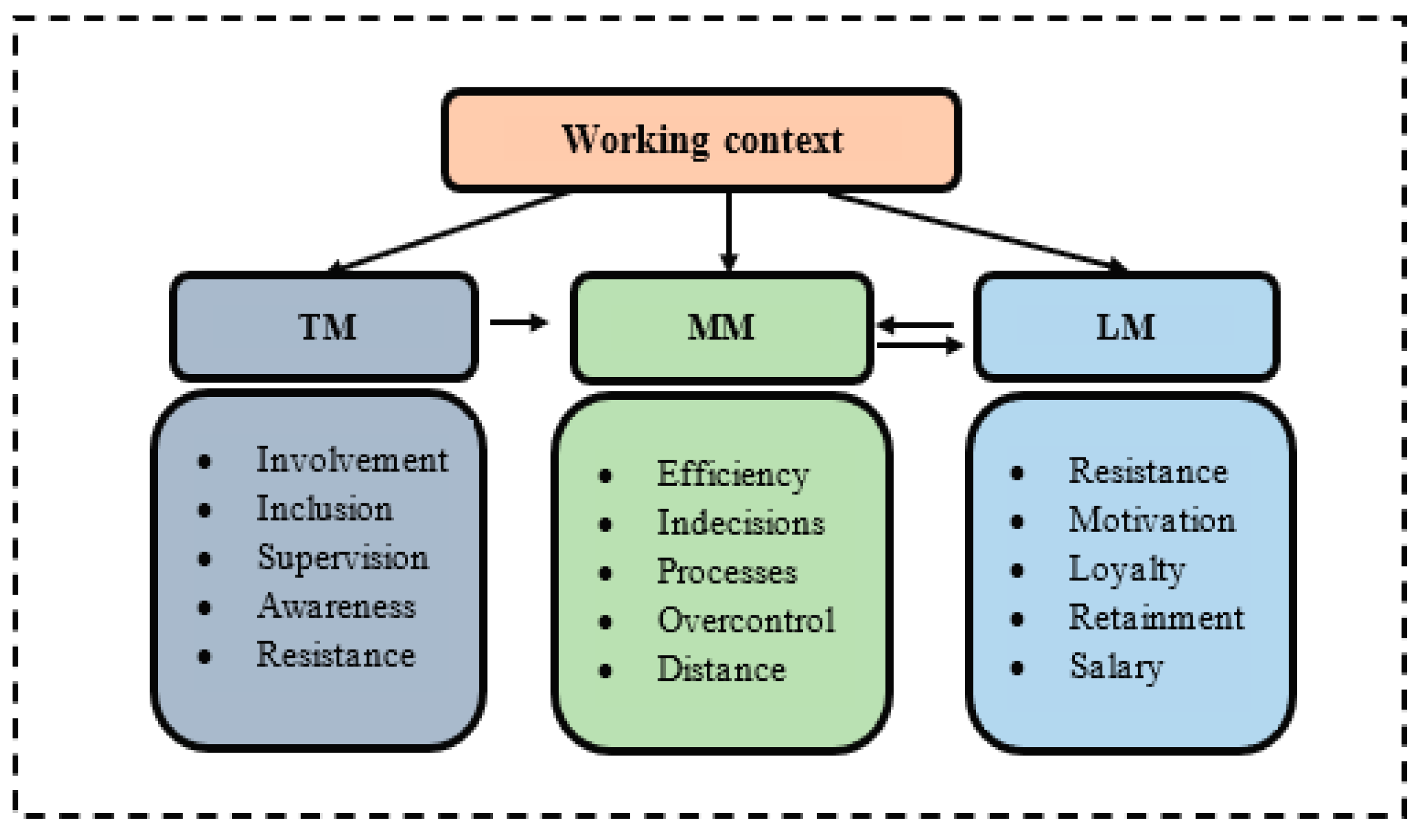

2. Strategic Planning, Change, and Management Levels

2.1. Improvement and Disruption

2.2. Resistance to Change and Retention

2.3. Management Levels

3. Research Setting

Empirical Setting and Context

4. Methods and Data Collection

4.1. Qualitative Approach

4.2. Results (Qualitative Data)

- (1)

- What do you consider essential for the implementation of strategic planning?

- (2)

- In your opinion, what contributions can your employees make to improve strategic planning?

- (3)

- Describe a situation in which communication did not go as expected in the workplace. How do you think communication could have been more effective in that situation?

- (4)

- Describe your relationship with your peers, department, directors, and other employees.

- (5)

- How can you create stronger relationships with the company’s employees?

- (6)

- Which areas most need your attention at the strategic planning level? In your experience what can be done differently to improve the mentioned areas?

- (7)

- From your perspective, what disruptions can there be in strategic planning? What are the solutions to these changes?

- (8)

- In your experience, what solutions do you consider viable to overcome resistance to change?

- (9)

- What factors do you consider indispensable for talent retention?

- (10)

- Describe how important is the integration of your team for you and how this can contribute to the company’s strategic planning.

- (11)

- What benefits can be made available to employees to increase their participation in the organization?

5. Quantitative Approach

5.1. Data Procedure

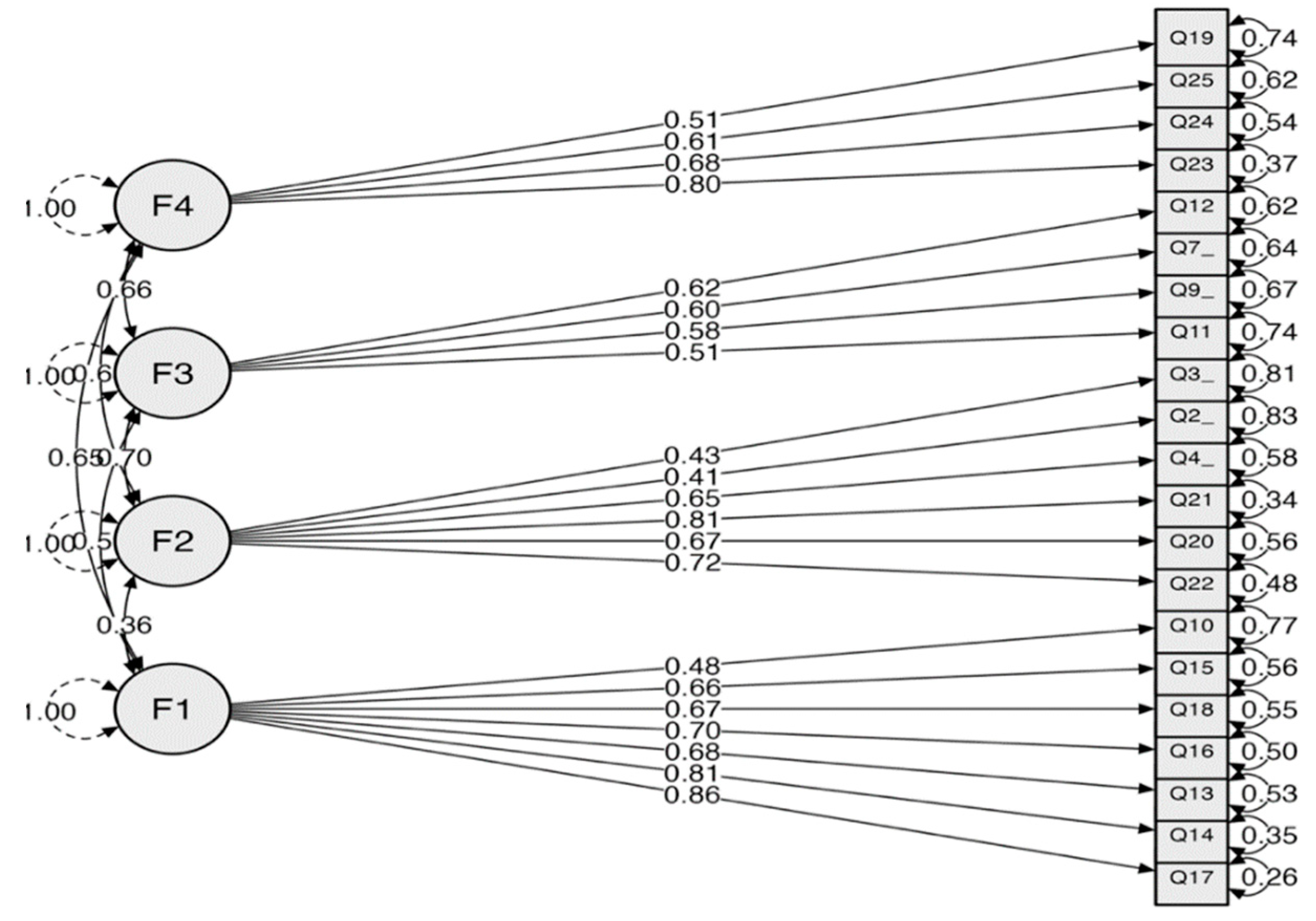

5.2. Results (Quantitative Data)

6. Discussion and Conclusions

7. Recommendations

8. Theoretical and Practical Implications

9. Limitations and Future Research Implications

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Aceituno, Alicia, Andrea Bernal, Jorge Pérez-Corrales, César Fernández-de-las-Peñas, Domingo Palacios-Ceña, and Javier Güeita-Rodríguez. 2022. The impact of digital physical therapy during COVID-19 lockdown in children with developmental disorders: A qualitative study. Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy 26: 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsawafi, Ahmed, Fred Lemke, and Ying Yang. 2021. The impacts of internal quality management relations on the triple bottom line: A dynamic capability perspective. International Journal of Production Economics 232: 107927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, Teresa. 1997. Motivating creativity in organizations: On doing what you love and loving what you do. California Management Review 40: 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrollahi, Alireza, and Bruce Rowlands. 2018. OSPM: A design methodology for open strategic planning. Information & Management 55: 667–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzengruber, Johanna, Martin Goetz, Herbert Nold, and Marco Woelfle. 2017. Effectiveness of managerial capabilities at different hierarchical levels. Journal of Managerial Psychology 32: 134–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arji, Goli, Hassein Ahmadi, Pejman Avazpoor, and Morteza Hemmat. 2023. Identifying resilience strategies for disruption management in the healthcare supply chain during COVID-19 by digital innovations: A systematic literature review. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked 38: 101199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balogun, Julia, and Gerry Johnson. 2004. Organizational restructuring and middle manager sensemaking. Academy of Management Journal 47: 523–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjorck, Martin, Mark Koelemay, Tilo Kölbel, Timothy Lees, S. Acosta, F. Bastos Goncalves, J. J. Kolkman, J. H. Lefevre, G. Menyhei, G. Oderich, and et al. 2017. Editor’s Choice—Management of the Diseases of Mesenteric Arteries and Veins: Clinical Practice Guidelines of the European Society of Vascular Surgery (ESVS). European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery 53: 460–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolivar, Manuel, Cristina Muñoz, and Laura Munõz. 2020. Characterising smart initiatives’ planning in smart cities: An empirical analysis in Spanish smart cities. Paper presented at 13th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance, online, September 23–25; pp. 585–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonn, Ingrid, and Chris Christodoulou. 1996. From Strategic Planning to Strategic Management. Long Range Planning 29: 543–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Book, Laura, Anthony Gatling, and Jungsun Kim. 2019. The effects of leadership satisfaction on employee engagement, loyalty, and retention in the hospitality industry. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism 18: 368–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossink, Bart, and Jan-Nico Blauw. 2002. Strategic ambitions as drivers of improvement at DaimlerChrysler. Measuring Business Excellence 6: 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyne, George, Julian Gould-Williams, Jennifer Law, and Richard M. Walker. 2002. Plans, Performance Information and Accountability: The Case of Best Value. Public Administration 80: 691–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, Fred, and Paul Yarnold. 1995. Principal Components Analysis and Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Edited by Laurence Grimm and Paul Yarnold. Reading and Understanding Multivariate Analysis. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 99–136. [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham, Marcus. 2022. Designing work that love people. Harvard Business Review 100: 66–75. [Google Scholar]

- Burnes, Bernard. 2015. Understanding resistance to change—Building on Coch and French. Journal of Change Management 15: 92–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachón-Rodríguez, Gabriel, Alicia Blanco-González, Camilo Prado-Román, and Cristina Del-Castillo-Feito. 2022. How sustainable human resources management helps in the evaluation and planning of employee loyalty and retention: Can social capital make a difference? Evaluation and Program Planning 95: 102171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cachón-Rodríguez, Gabriel, Camilo Prado-Román, and Alicia Blanco-González. 2021. The relationship between corporate identity and university loyalty: The moderating effect of brand identification in managing an institutional crisis. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 29: 265–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Gilad, and Paul Bliese. 2002. The role of different levels of leadership in predicting self- and collective efficacy: Evidence for discontinuity. Journal of Applied Psychology 87: 549–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claus, Lisbeth. 2019. HR disruption—Time already to reinvent talent management. BRQ Business Research Quarterly 22: 207–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, Jose. 1993. What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. Journal of Applied Psychology 78: 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, Lee Joseph. 1951. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16: 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Val, Manuel, and Clara Fuentes. 2003. Resistance to change: A literature review and empirical study. Management Decision 41: 148–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, Sarah, and Matthew Sanders. 2010. Meaningful work? Nonprofit marketization and work/life imbalance in popular autobiographies of social entrepreneurship. Organization 17: 437–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diefenbach, Thomas, and Jonh Silince. 2011. Formal and informal hierarchy in different types of organization. Organization Studies 32: 1515–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzung, Thuy, and Fang Lo. 2023. How does top management team diversity influence firm performance? A causal complexity analysis. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 186: 122162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbanna, Ammany, and Mike Newman. 2022. The bright side and the dark side of top management support in Digital Transformation—A hermeneutical reading. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 175: 121411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engberg, Robert, Sven Horte, and Magnus Lundback. 2015. Strategy implementation and organizational levels: Resourcing for innovation as a case. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance 2: 157–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erwin, Dennis, and Andrew Garman. 2010. Resistance to organizational change: Linking research and practice. Leadership & Organization Development Journal 31: 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzamel, Mahmoud, Hugh Willmott, and Frank Worthington. 2001. Power, Control and Resistance in ‘The Factory That Time Forgot’. Journal of Management Study 38: 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, Catherine, and Jonathan Morris. 2013. Managing the neo-bureaucratic organization: Lessons from the UK’s prosaic sector International. Journal of Human Resource Management 24: 1376–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, Peter, and Aandré Spicer. 2008. Beyond power and resistance. Management Communication Quarterly 21: 301–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, Peter, and Granham Sewell. 2002. Looking for the good soldier, Svejk: Alternative modalities of resistance in the contemporary workplace. Sociology 36: 857–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, Steven, Torsten Schmid, and Bill Wooldridge. 2008. The middle management perspective on strategy process: Contributions, synthesis, and future research. Journal of Management 34: 1190–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, William, Jonh Hassar, Jonh Morris, and Julie Cox. 2019. The changing nature of managerial work: The effects of corporate restructuring on management jobs and careers. Human Relations 72: 473–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, Peter, Eva Benkova, and Beáta Mihalcova. 2019. The Effects of Using Strategic Planning as a Managerial Tool: A Case of Industrial Companies. Polish Journal of Management Studies 20: 145–60. [Google Scholar]

- George, Bert. 2017. Does strategic planning ‘work’ in public organizations? Insights from Flemish municipalities. Public Money & Management 37: 527–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, Bert, Richard Walker, and Joost Monster. 2019. Does strategic planning improve organizational performance? A meta-analysis. Public Administration Review 79: 810–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannoccaro, Ilaria. 2018. Centralized vs. decentralized supply chains: The importance of decision maker’s cognitive ability and resistance to change. Industrial Marketing Management 73: 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaister, Keith, and Richard Falshaw. 1999. Strategic Planning: Still going Strong? Long Range Planning 32: 107–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Chao, and Charllotte Ren. 2011. Middle managers’ strategic role in the corporate entrepreneurial process: Attention-based effects. Journal of management 37: 1586–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyadeen, Dave, Daniel Henstra, Shivani Kaup, and Grace Wright. 2023. Evaluating the quality of municipal strategic plans. Evaluation and Program Planning 96: 102186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellberg, Rolland, and Eivind Fauskanger. 2022. Learning of quality improvement theory—Experiences with reflective learning from a student perspective. International Journal of Lean Six Sigma. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermano, Victor, and Natalia Martín-Cruz. 2016. The role of top management involvement in firms performing projects: A dynamic capabilities approach. Journal of Business Research 69: 3447–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersperger, Anna, Eduardo Oliveira, Sofia Pagliarin, Gaetan Palka, Peter, and Janine Bolliger. 2018. Urban land-use change: The role of strategic spatial planning. Global Environmental Change 51: 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hober, Bjoern, and Mario Schaarschimt. 2021. Internal idea contests: Work environment perceptions and the moderating role of power distance. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge 6: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hortovanyi, Lilla, Roland Szabo, and P. Fuzes. 2021. Extension of the strategic renewal journey framework: The changing role of middle management. Technology in Society 65: 101540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehn, Karen, Gregory Northcraft, and Margaret Neale. 1999. Why differences make a difference: A field study of diversity, conflict and performance in workgroups. Administrative Science Quarterly 44: 741–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Don, Vinod Kumar, and Uma Kumar. 2012. Relationship between quality management practices and innovation. Journal Operational Management 30: 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krier, Laura. 2022. A framework for shared leadership: A perspective on strategic planning for academic libraries. The Journal of Academic Librarianship 62: 899–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, Ann, and Malvina Klag. 2014. Critical junctures in strategic planning: Understanding failure to enable success. Organizational Dynamics 43: 274–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, David, Michael Mc Guire, and J. Kim. 2017. Collaboration, strategic plans, and government performance: The case of efforts to reduce homelessness. Public Management Review 20: 360–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinwand, Paul, Blair Shepard, and M. Mani. 2022. Reinventing your leadership team. Harvard Business Review 100: 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Jing, Richard Pike, and Roszaini Haniffa. 2008. Intellectual capital disclosure and corporate governance structure in UK firms. Accountability Business Research 38: 137–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lines, Brian, Kenneth Sullivan, Jake Smithwick, and Josh Mischung. 2015. Overcoming resistance to change in engineering and construction: Change management factors for owner organizations. Journal of Business Research 160: 113782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loehlin, Jonh. 2004. Latent Variable Models: An Introduction to Factor, Path, and Structural Equation Analysis, 4th ed. Hillsdale: Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Marôco, João. 2021. Análise de Equações Estruturais, Fundamentos teóricos, Software & aplicações, 3rd ed. Pêro Pinheiro: ReportNumber, Lda. [Google Scholar]

- Mintzberg, Henry. 1994. Rethink Strategic Planning Part I: Pitfalls and Fallacies. Long Range Planning 27: 12–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, Monika, Christian Huber, and Martin Messner. 2019. Meaningful work at a distance: A case study in a hospital. European Management Journal 37: 719–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumby, Dennis, Robyn Thomas, I. Marti, and David Seidl. 2017. Resistance Redux. Organization Study 38: 1157–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munjuri, Mercy Gacheri, and Raquel Muthoni Maina. 2013. Workforce diversity management and employee performance in the banking sector in Kenya. DBA Africa Management Review 3: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Murnighan, Keith, and Donald Conlon. 1991. The dynamics of intense workgroups: A study of British string quartets. Administrative Science Quarterly 36: 165–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadkarni, Sucheta, and Pamela Barr. 2008. Environmental context, managerial cognition, and strategic action: An integrated view. Strategic Management Journal 29: 1395–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, Jum. 1994. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed. New York: Tata McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Ou, Amy, Anne Tsui, Angelo Kinicki, David Waldman, Z. Xiao, and Linda Song. 2014. Humble chief executive officers’ connections to top management team integration and middle managers’ responses. Administration Science Quarterly 59: 34–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, Rolland. 2015. Non-work at work: Resistance or what? Organization 22: 351–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, Jonh, Elizabeth Freeman, and Richard Robinson. 1987. Formal Strategic Planning and Financial Performance. Academy of Management Review 12: 658–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posch, Arthur, and Garaus Cristian. 2020. Boon or Curse? A Contingent View on the Relationship between Strategic Planning and Organizational Ambidexterity. Long Range Planning 53: 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranucci, Rebecca, and Shirley Wang. 2022. Resilience in Top Management Teams: Responding to crisis by focusing on the future. Long Range Planning 15: 102268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razek, Mohamed, Hesham Basssioni, and Ahmed Mobarak. 2008. Causs of delay in building constructions projects in Egypt. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 134: 831–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouhani, Saeed, and Mehdi Ghazanfari. 2012. Evaluation model of business intelligence for enterprise systems using fuzzy TOPSIS. Expert Systems with Applications 39: 3764–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schabram, Kira, and Sally Maitlis. 2017. Negotiating the challenges of a calling: Emotion and enacted sensemaking in animal shelter work. Academy of Management Journal 60: 584–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, Benedikt, Kevin Orr, and Jeffrey Hughes. 2023. My colleagues (do not) think the same: Middle managers’ shared and separate realities in strategy implementation. Journal of Business Research 160: 113782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahab, Yasir, Collins Ntim, Chengang Ye, Farid Ullah, and Samuel Fosu. 2018. Environmental policy, environmental performance, and financial distress in China: Do top management team characteristics matter? Business Strategic Environment 27: 1635–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, George. 1980. Strategic Planning: What Every Manager Should Know. Strategic Management Journal 1: 191–92. [Google Scholar]

- Stensaker, Inger, Joyce Falkenberg, and Kjell Gronhaug. 2008. Implementation activities and organizational sensemaking. Journal of Applied Behavior Sciences 44: 162–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarí, Juan, Jorge Pereira-Moliner, Eva Pertusa-Ortega, Maria López-Gamero, and José Molina-Azorín. 2017. Does quality management improve performance or vice versa? Evidence from the hotel industry. Service Business 11: 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Knippenberg, Daan, and Michaélla Schippers. 2007. Workgroup diversity. Annual Review of Psychology 58: 515–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vecchiato, Riccardo. 2012. Environmental uncertainty, foresight and strategic decision making: An integrated study. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 79: 436–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Junhua, Hao Song, Ting Fu, Molly Behan, Lei Jie, Yingxian He, and Qianggiang Shangguan. 2022. Crash prediction for freeway work zones in real time: A comparison between Convolutional Neural Network and Binary Logistic Regression model. International Journal of Transportation Science and Technology 11: 484–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warrick, Donald. 2022. Revisiting resistance to change and how to manage it: What has been learned and what organizations need to do. Business Horizons 66: 433–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weston, Marla. 2020. Strategic planning in an age of uncertainty: Creating clarity in uncertain times. Nurse Leader 18: 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ybema, Sierk, and Martha Horvers. 2017. Resistance through compliance: The strategic and subversive potential of frontstage and backstage resistance. Organizational Study 38: 1233–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Classification | Total Sample (n = 14) | Percentage (100%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 7 | 50.0 |

| Male | 7 | 50.0 | |

| Age | 18–25 | 5 | 35.7 |

| 26–35 | 4 | 28.6 | |

| 36–45 | 2 | 14.3 | |

| 46–55 | 3 | 21.4 | |

| Country | Portugal | 5 | 35.7 |

| Greece | 2 | 14.3 | |

| Poland | 2 | 14.3 | |

| Organization | Other | 5 | 35.7 |

| Private | 11 | 78.6 | |

| Public | 3 | 21.4 | |

| Company Size | <500 workers | 10 | 71.4 |

| 501–999 workers | 3 | 21.4 | |

| >1000 workers | 1 | 7.2 | |

| Working sector | Technology | 7 | 50.0 |

| Management | 5 | 35.5 | |

| Education | 1 | 7.1 | |

| Food | 1 | 7.1 |

| Characteristic | Classification | Total Sample (n = 204) | Percentage (100%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 95 | 46.57 |

| Male | 106 | 51.96 | |

| Other | 3 | 1.47 | |

| Age | 18–25 | 71 | 34.80 |

| 26–35 | 79 | 38.73 | |

| 36–45 | 33 | 16.18 | |

| 46–55 | 16 | 7.84 | |

| 56–65 | 4 | 1.96 | |

| Over 65 | 1 | 0.49 | |

| Academic Qualifications | Basic education | 2 | 0.98 |

| Middle school | 48 | 23.53 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 73 | 35.78 | |

| Master’s degree | 75 | 36.76 | |

| Ph.D. | 4 | 1.96 | |

| Other | 2 | 0.98 | |

| Management Level | Middle | 76 | 37.25 |

| Lower | 128 | 62.75 | |

| Country | Portugal | 45 | 25.49 |

| Poland | 46 | 22.55 | |

| United Kingdom | 44 | 21.57 | |

| Other | 62 | 30.39 |

| Factors and Items | PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | PC4 | Cronbach’s Alpha by Component |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1- Employee Engagement | 0.866 | ||||

| Skills—Q17 | 0.822 | ||||

| Feedback—Q14 | 0.776 | ||||

| Appreciation—Q13 | 0.771 | ||||

| Growth—Q16 | 0.763 | ||||

| Participation—Q18 | 0.681 | ||||

| Job retention—Q15 | 0.588 | ||||

| Encouragement—Q10 | 0.524 | ||||

| F2- Organizational Development | 0.780 | ||||

| Intentions—Q22 | 0.737 | ||||

| New perspective—Q20 | 0.723 | ||||

| Collaboration—Q21 | 0.668 | ||||

| Bureaucracy—Q4 | 0.598 | ||||

| Communication—Q2 | 0.592 | ||||

| Guidelines—Q3 | 0.555 | ||||

| F3- Employee Motivation | 0.663 | ||||

| Teamwork—Q11 | 0.652 | ||||

| Training—Q9 | 0.620 | ||||

| Perks—Q7 | 0.604 | ||||

| Work satisfaction—Q12 | 0.500 | ||||

| F4- Sustainable Inclusion | 0.730 | ||||

| Environmentally messages—Q23 | 0.665 | ||||

| Sustainable training—Q24 | 0.620 | ||||

| Inclusion—Q25 | 0.617 | ||||

| Interaction—Q19 | 0.575 | ||||

| KMO | 0.885 | ||||

| Bartlett´s Test of Sphericity | χ2(210) = 1638.957; Sig. < 0.001 | ||||

| Cronbach´s Alpha Global | 0.889 | ||||

| Principal Components | Unrotated Solution | Rotated Solution | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eigenvalue | Proportion | Cumulative | SumSq. | Proportion | Cumulative | |

| Variance | Loadings | Variance | ||||

| PC1 | 6.699 | 0.319 | 0.319 | 4.172 | 0.199 | 0.199 |

| PC2 | 2.496 | 0.119 | 0.438 | 2.901 | 0.138 | 0.337 |

| PC3 | 1.225 | 0.058 | 0.496 | 2.318 | 0.110 | 0.447 |

| PC4 | 1.173 | 0.056 | 0.552 | 2.202 | 0.105 | 0.552 |

| Index | Value |

|---|---|

| Comparative fit index (CFI) | 0.932 |

| Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) | 0.922 |

| Bentler–Bonett normed fit index (NFI) | 0.902 |

| Information criteria | |

| Log-likelihood | −18,665.809 |

| Number of free parameters | 69.000 |

| Akaike (AIC) | 37,469.618 |

| Bayesian (BIC) | 37,698.569 |

| Other fit measures | |

| Root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) | 0.052 |

| RMSEA 90% CI lower-bound | 0.040 |

| RMSEA 90% CI upper-bound | 0.064 |

| Standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR) | 0.055 |

| Hoelter’s critical N (α = 0.05) | 155.208 |

| Hoelter’s critical N (α = 0.01) | 165.838 |

| Goodness of fit index (GFI) | 0.985 |

| 95% Confidence Interval | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Indicator | Symbol | Estimate | Std. Error | z-Value | p-Value | Lower | Upper |

| F1 | Q17 | λ11 | 25.907 | 1.741 | 14.881 | <0.001 | 22.495 | 29.319 |

| Q14 | λ12 | 21.980 | 1.629 | 13.494 | <0.001 | 18.788 | 25.173 | |

| Q13 | λ13 | 18.143 | 1.701 | 10.663 | <0.001 | 14.808 | 21.478 | |

| Q16 | λ14 | 21.188 | 1.908 | 11.104 | <0.001 | 17.448 | 24.928 | |

| Q18 | λ15 | 16.717 | 1.610 | 10.384 | <0.001 | 13.562 | 19.872 | |

| Q15 | λ16 | 17.531 | 1.722 | 10.182 | <0.001 | 14.156 | 20.905 | |

| Q10 | λ17 | 13.071 | 1.881 | 6.950 | <0.001 | 9.385 | 16.757 | |

| F2 | Q22 | λ21 | 15.473 | 1.391 | 11.121 | <0.001 | 12.746 | 18.200 |

| Q20 | λ22 | 12.992 | 1.300 | 9.997 | <0.001 | 10.445 | 15.539 | |

| Q21 | λ23 | 16.152 | 1.237 | 13.062 | <0.001 | 13.728 | 18.575 | |

| Q4 | λ24 | 10.556 | 1.102 | 9.581 | <0.001 | 8.396 | 12.715 | |

| Q2 | λ25 | 8.936 | 1.591 | 5.615 | <0.001 | 5.817 | 12.056 | |

| Q3 | λ26 | 7.787 | 1.305 | 5.968 | <0.001 | 5.230 | 10.344 | |

| F3 | Q11 | λ31 | 7.675 | 1.133 | 6.772 | <0.001 | 5.454 | 9.896 |

| Q9 | λ32 | 10.628 | 1.354 | 7.847 | <0.001 | 7.974 | 13.283 | |

| Q7 | λ33 | 10.046 | 1.247 | 8.055 | <0.001 | 7.602 | 12.490 | |

| Q12 | λ34 | 11.017 | 1.304 | 8.446 | <0.001 | 8.461 | 13.574 | |

| F4 | Q23 | λ41 | 20.068 | 1.645 | 12.199 | <0.001 | 16.844 | 23.293 |

| Q24 | λ42 | 15.533 | 1.562 | 9.947 | <0.001 | 12.472 | 18.593 | |

| Q25 | λ43 | 16.347 | 1.854 | 8.817 | <0.001 | 12.713 | 19.980 | |

| Q19 | λ44 | 13.048 | 1.849 | 7.055 | <0.001 | 9.423 | 16.673 | |

| F1—Employee Engagement | F2—Organizational Development | F3—Employee Motivation | F4—Sustainable Inclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q10—Encouragement | Q03—Guidelines | Q12—Work Satisfaction | Q19—Interaction |

| Q15—Job Retention | Q02—Communications | Q07—Perks | Q25—Inclusion |

| Q18—Participation | Q04—Bureaucracy | Q09—Training | Q24—Sustainable training |

| Q16—Growth | Q21—Collaboration | Q11—Teamwork | Q23—Environmental messages |

| Q14—Feedback | Q20—New perspectives | ||

| Q17—Skills | Q22—Intentions |

| Index | Value |

|---|---|

| Comparative fit index (CFI) | 0.899 |

| Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) | 0.885 |

| Other Fit measures | |

| Root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) | 0.065 |

| RMSEA 90% CI lower-bound | 0.052 |

| RMSEA 90% CI upper-bound | 0.077 |

| Goodness of fit index (GFI) | 0.976 |

| R2 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Middle Management | Lower Management | |

| Q17 | 0.723 | 0.763 |

| Q14 | 0.684 | 0.623 |

| Q13 | 0.444 | 0.509 |

| Q16 | 0.536 | 0.438 |

| Q18 | 0.468 | 0.449 |

| Q15 | 0.418 | 0.486 |

| Q10 | 0.138 | 0.404 |

| Q22 | 0.410 | 0.742 |

| Q20 | 0.368 | 0.554 |

| Q21 | 0.668 | 0.671 |

| Q4 | 0.451 | 0.379 |

| Q2 | 0.126 | 0.263 |

| Q3 | 0.197 | 0.181 |

| Q11 | 0.283 | 0.200 |

| Q9 | 0.331 | 0.305 |

| Q7 | 0.346 | 0.391 |

| Q12 | 0.251 | 0.752 |

| Q23 | 0.670 | 0.601 |

| Q24 | 0.513 | 0.371 |

| Q25 | 0.375 | 0.336 |

| Q19 | 0.268 | 0.256 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gandrita, D.M. Improving Strategic Planning: The Crucial Role of Enhancing Relationships between Management Levels. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13100211

Gandrita DM. Improving Strategic Planning: The Crucial Role of Enhancing Relationships between Management Levels. Administrative Sciences. 2023; 13(10):211. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13100211

Chicago/Turabian StyleGandrita, Daniel Mandel. 2023. "Improving Strategic Planning: The Crucial Role of Enhancing Relationships between Management Levels" Administrative Sciences 13, no. 10: 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13100211

APA StyleGandrita, D. M. (2023). Improving Strategic Planning: The Crucial Role of Enhancing Relationships between Management Levels. Administrative Sciences, 13(10), 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13100211