Abstract

The three lockdown periods across 2020–2021 due to COVID-19 had significant consequences for police. Pandemic lockdown experiences were explored based on online interviews with 25 officers of varied ranks and from across five regions in England and Wales. The analysis demonstrates the existence of two counter-prevailing dynamics in the working world of police in England and Wales across the three lockdown periods. Changing government directives, deteriorating relationships between the police and the public and senior officers’ sensitivity to the needs of the workforce, were foci of concern and discussion. On reflection, officers acknowledged that relationships between senior management and police improved over the three lockdowns. However, officers found it difficult to balance the demands of the profession and the claims of the state while seeking to retain policing by consent with an increasingly fractious public unsettled by restrictions to their freedom of movement and government activity.

1. Introduction

Despite a growing body of literature that has examined the role of the police during the COVID-19 pandemic there has been less work on police officers’ views of policing across the three periods of the 2020–2021 lockdowns, the UK government directives, and the impact of both on the relationship between police and the public. As the police working environment sought to adapt to the national health emergency that would require strict law enforcement and a commitment to public safety, officers sought to retain public consent and support for their work practices. This paper draws on online interviews with police officers and their experiences of policing across individual lockdown periods. The analysis demonstrates the existence of two counter-prevailing dynamics in the working world of police in England and Wales across the three lockdown periods. Firstly, an increased sensitivity on the part of senior leaders to the needs of the workplace and the state (aligned to models of serving leadership) and secondly, deteriorating relationships between the police and the public (testing the model of policing by consent). Seeking to balance these dynamics brought both stress and disappointment to officers. The paper tracks the pressures on the police internally and the breakdown in relationships externally with the public. These pressures can be attributed in part to the contradictions in their law enforcement and protective roles, contradictions exacerbated by the additional factors, detailed later, across the periods of the three national lockdowns. The paper builds on a series of papers in an interlinked series reporting early empirical evidence of the perceptions and impacts on police personnel during the COVID-19 pandemic experinced by police officers and non-warranted police staff in England and Wales (Brown and Fleming 2022; Fleming and Brown 2021; Fleming and Brown 2023).

The first COVID-19 cases were confirmed in January 2020 and the first national lockdown took place on 26 March, a few weeks before the Easter break lasting until May 2020. Thereafter, there were isolated regional lockdowns until two further national lockdowns commenced on 5 November and 26 January, respectively, ending in March 2021. During these restrictions, the role of the police evolved in accordance with new legislation and government guidance that focused on the police assisting public health officials and enforcing the Health Protection (Coronavirus) Regulations 2020, when restrictions were contravened (Ralph et al. 2022). Perhaps, to reduce potential confrontation, the UK’s College of Policing advised police officers to adopt a ‘four E‘ approach to the enforcement of the legislation. First, ‘Engage’ with the public, ask them why they are out and about and listen to their responses. Second, ‘Explain’ the social distancing regulations and why they are in place (e.g., risks to public health and protecting the National Health Service, NHS). Third, ‘Encourage’ individuals to follow the regulations and ask them to return home if they have no reasonable grounds to be out. Finally, as a last resort, officers may ‘Enforce’ the law, fining people for breaching the legislation and use force to take individuals home. Such enforcement is heavily reliant on police officers’ ability to communicate shared values and seek public consent1. As police in England and Wales and beyond, sought to manage this new and frightening environment, academics and others tried to make sense of the impact of COVID-19 on policing, police officers/staff and the public both in England and Wales, and internationally.

2. Literature Review

2.1. What We Know

We have learned a great deal about policing COVID-19 from international studies See, for example, Papazoglou et al. (2020); Kniffin et al. (2021); Mehdizadeh and Kamkar (2020), Drew and Martin (2020); Sadiq (2020); Stogner et al. (2020); Frenkel et al. (2021). To date, the empirical work of Fleming and Brown (2022), and Newiss et al. (2022), provide nuanced understandings of the impact on police personnel working under conditions of COVID-19 in England and Wales. Brown and Fleming (2022) showed differential impacts on women police personnel compared to their male colleagues with respect to additional stresses experienced because of greater burdens placed on them for home schooling and care of elderly and vulnerable relatives. In addition, Thompson et al. (2022) commented on the adverse physical and psychological health effects on front-line law enforcement officers. Laufs and Waseem’s (2020) systematic review of the challenges facing law enforcement during general crises identified: (1) police-community relations; (2) the psychological and mental wellbeing of police officers; (3) intra-organisational challenges (such as resource allocation or staffing) as well as inter-organisational collaboration, cooperation and communication. Other pressures included dealing with a public who, while conceding that police were ‘doing the best they can’ (Ghaemmaghami et al. 2021, p. 2323) were perceived as largely ‘ineffective’ in their responses, citing perceptions of inequitable policing and lack of visibility and communication as their chief concerns.

Other academic research related to policing the pandemic has noted the disproportionate numbers of penalties given to those from diverse cultural backgrounds leading to perceived over-policing and intensification of racialized policing. Fleming and Brown (2023) report that by 8th June 2020, a total of 15,715 Fixed Penalty Notices (FPN) had been recorded by forces in England and Wales for breaches of government regulations during the first lockdown period2. Figures released by London’s Metropolitan Police Force in June 2020 revealed that despite only making up around 12% of the population, black individuals accounted for 26 per cent of the FPNs issued3. Additionally, for COVID-19 legislation breaches, black individuals accounted for 31 per cent of all arrests during the lockdown period. This finding is repeated elsewhere. Boon-Kuo et al. (2021) who report that despite being only 3% of Australia’s population, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples were disproportionately subject to coercive COVID-19-related powers in the first lockdown period (15 March to 15 June 2020).

2.2. Gaps

Fewer studies have focussed on any shifts of emphasis over the course of the pandemic. Ralph et al. (2022) charted distinct stages in police’s online engagement with the public in the UK over time. At first, police engaged with citizens online to maintain contact with the communities that they serve. This evolved to them taking a more active role in sharing content linked to the COVID-19 pandemic as part of their public service role in protecting the public. As the lockdowns continued, they refrained from discussing the COVID-19 pandemic because they perceived this to be detrimental to police public relations and instead used social media to relay stories relating to non-pandemic-related police activity.

Reporting on the first three waves of a longitudinal panel survey covering periods of the first lockdown and lockdown easing across England and Wales, Jackson and Bradford (2021) found high levels of compliance with restrictions in the first lockdown. They suggest that whilst social distancing was made a legal requirement, people responded out of a sense of collective harm reduction rather than the deterrent effect of law enforcement. By wave two as restrictions were eased, worry about catching COVID-19 was a positive predictor of compliance: people who were most concerned were more likely to comply most fully with lockdown restrictions. Levels of concern about catching the virus were dropping at this stage, and, according to Jackson and Bradford (2021), this may have partly explained why compliance rates went down marginally. By wave three when restricted behaviours were no longer formally illegal, fewer people complied generally.

2.3. Prevailing Context

While existing literature and ongoing research is pivotal to our understanding of how police manage the dual roles of keeping people safe and enforcing restrictive regulations in a national health emergency—we should not overlook the context within which such activity takes place. Policing does not take place in a vacuum. Research questions that ask specifically about levels of satisfaction/dissatisfaction with the policing of COVID-19 restrictions, police capacity to monitor compliance and their effectiveness in alleviating fear and anxiety are of course important, but responses need to be considered in the broader context of governance and existing and evolving relationships between the police and the public.

In England and Wales, there were issues during the lockdown periods relating to the police, which arguably adversely affected the public’s4 attitudes towards them. Evidence of sexist behaviours, allegations of corruption, failed investigations and poor performance across many forces was scrutinised heavily in the media. In June 2020 Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue (HMICFR) placed 6 of England and Wales 43 forces in special measures.5 These forces included the Metropolitan Police and that of Greater Manchester—two of the biggest forces in the United Kingdom. Perceptions of over-policing anti-racial protests in Bristol where protestors were charged with criminal damage further divided the public6.

In March 2021, a young woman, Sarah Everard was abducted and murdered by a serving Metropolitan Police officer. An officer used COVID restriction regulations and his police identity card to kidnap, rape and murder her. Wayne Couzen’s inappropriate and unedifying past behaviour at his workplace soon became common knowledge, as did his nickname, the ‘Rapist’. Many of Couzen’s colleagues have since been investigated, sacked and/or convicted for ‘racist, misogynist, sexist, homophobic, Islamophobic and ableist’ messages shared on mobile phones7. The investigations continue (Casey 2022).

A vigil in Sarah Everard’s memory resulted in an anti-violence demonstration and was deemed illegal under a national coronavirus lockdown. The police response resulted in media images of police restraining women protestors. Despite the policing of the vigil being more nuanced than was allowed for by the media generally (Stott et al. 2022), the images were enough to cause disquiet. Those arrested and charged at the Sarah Everard vigil had their charges dropped when the Crown Prosecution Service declined to prosecute8.

Such reflections, of course, do not necessarily mean that the public were increasingly averse to police during the COVID-19 lockdowns—the context does, however, provide a relevant backdrop to an understanding of the sensitive environment that existed during this period in England and Wales. However, there is evidence that public approval of police was declining: a YouGov poll9 showed that in February 2020, seven out of ten Britons said they thought the police were doing well. By March 2022 just under half of the public (53%) thought so. The percentage saying that the police are doing a bad job has more than doubled from 15% to 37%.

2.4. Enforcing versus Serving

The British model of policing enshrined in Robert Peel’s doctrine, the people are the police, and the police are the people steers a balance between law enforcement (i.e., security of the state) and serving the public (i.e., protecting the citizen). The first may involve the exercising of coercive control, for example, in maintaining public order, while the second may involve more community-enhancing strategies such as harm reduction and meaningful community engagement. Loader (2016, pp. 429–30) points out that Peel’s principles ‘speak only partially to the challenges of urban policing’ nowadays. Certainly, the ideals associated with Peel’s principles take on a new perspective when police seek to secure ‘observance of the law’ and at the same time ‘seek and preserve public favour and ‘secure and maintain the respect and approval of the public’. This is particularly the case when they do so in an ‘extreme environmental situation’ (Fleming and Brown 2022) that prioritizes public safety and at the same time vigorously enforces government legislation and regulations, not always with citizens’ consent (see Newiss et al. 2022; Ghaemmaghami et al. 2021; Laufs and Waseem 2020).

Previously, there have been degrees of oscillation between the enforcing and serving functions of police (Waters 1996). There has been criticism of them in terms of under-policing their protective or service role and over-policing their enforcement duties, delivering unequal treatment with respect to racially diverse communities (Boehme et al. 2022). In recent years, moves towards procedural justice models of policing in Anglo-speaking countries has enhanced the service role (Aston et al. 2021) and in England and Wales has become strongly associated with ideas of normative compliance, public confidence and support and a commitment to democratic modes of policing (Kyprianides et al. 2022).

However, as others have noted, (Ghaemmaghami et al. 2021; Laufs and Waseem 2020 for example), the COVID pandemic and the policing of it put great strain on this balance. On the one hand, the government introduced, at times random and without notice, COVID limiting directives, coupled with legislation10 and multiple regulations11 severely restricting freedom of movement. On the other hand, police found themselves as part of the messaging to preserve and protect life as the virus wreaked havoc on the health and wellbeing of the nation’s citizens (Ralph et al. 2022). Kyprianides et al. (2022, p. 505) observed that securing public consent remained a core aim of policing during this time but that “the pandemic had profound effects on police organisations, the ways they work, [and] their relationships with the publics they serve”. Mills et al. (2021) noted the lack of understanding on the part of both police and the public about the new rules and how to respond to the various dictates issued by the government. As the pandemic persisted, retaining public consent was fractured, manifest in anti-mask and anti-lockdown protests, as well as reduced compliance with public health regulations (Sargeant et al. 2022). Sargeant et al. (2022) note the paradox between the need, rightly, to question the extension of police powers in a democracy with the need to effectively achieve containment of the virus from its lethal consequences. Thus, the tension between enforcing the law and the government’s directives and seeking to police by consent became strained across the lockdown periods.

3. Conceptual Framing

3.1. Developing Serving Behaviours under Extreme Conditions

We have previously characterized the pandemic lockdown phenomena as an “extreme environmental situation” (Fleming and Brown 2022). Just as procedural justice is pivotal to securing public support for policing, it is just as important for police to receive support from the police leadership. Christensen-Salem et al. (2021) suggest that under such circumstances there is a need for professionals such as the police not only to serve the community but also to service relationships within their own organization. They define these needs in terms of building unity of purpose and solidarity. What they term ‘servant leadership’ facilitates social relationships through acting in a serving capacity thereby providing others with a sense of care and belonging. Creating a serving culture requires harnessing social resources such as trust and support that limits depletion of the individual’s personal resilience and boosts their coping capacities especially under conditions of crisis. Team level servant leadership focusses on developing subordinates’ abilities and knowledge, which in turn models their own serving behaviours. Christensen-Salem et al. (2021) propose a cascading effect which, in a hierarchical organization such as the police, requires senior management (chief officers) to act as servant leaders, exercising concern for their immediate subordinates (superintendents) by aligning the organisation’s values with actual behaviours. Such behaviour motivates replication with their immediate staff etc., through to the rank and file at the level of constable. Having established a serving culture, subsequent employees’ behaviours reproduce responsiveness, empathy and assurance when serving customers that the organization is dedicated to protecting. As the authors state (Christensen-Salem et al. 2021, p. 833), service performance reflects unit members’ competence and willingness to perform core parts of their service-related tasks through conscientious application of high service standards.

3.2. Procedural Justice

We have discussed the importance of procedural justice (PJ) principles in the delivery of policing. Hough et al. (2017) define this in terms of the practice of authority and power i.e., fairness with which these are exercised. They say PJ, as applied to the police, predicts that when officers treat people with respect and dignity, utilise fair decision-making processes and allow them a voice in the interaction, those officers communicate that the citizen is of worth and value and facilitate reciprocal compliance. Moreover, this also demonstrates that power is balanced by due process within models of propriety and legality. As such, people are more likely to grant police legitimacy and defer to their authority. Kyprianides et al. (2022) argue that PJ principles also operate internally requiring police leaders to communicate clearly and effectively with their staff and listen and take on board their perspectives. They report that a positive organisational climate was associated with increased police officer health and well-being during the pandemic and less enthusiasm for the use of force in policing the lockdowns. Sargeant et al. (2022) found from an Australian study that the police’s use of procedural justice was a strong correlate of the public’s willingness to empower the police during COVID-19. Specifically, when they believed the police were procedurally just in the way they enforced social distancing rules, they were also more willing to empower the police to enforce these social distancing restrictions. Finally, participants who took part in a study by Simpson and Sandrin (2022) who perceived officers to be more procedurally just were also more favourable in their judgments of police performance during the pandemic.

The present study utilises online interviews with police officers to assess police officers’ perceptions of government directives, the relationship between the police and the public, the importance of procedural justice and the perceptions of the relevance of servant leadership to a positive organisational climate across the three lockdown periods.

4. Methods

4.1. On-Line Interviews

Our exploration of these issues is based on online semi-structured interviews with 25 officers of varied ranks and from across five regions in England and Wales. The interviews were conducted across April/June in 2021 and were approximately 50 min in length. Snowball sampling was used to recruit the officers. This sampling technique is used extensively in qualitative research particularly when a population is hard to accrue. The participants are selected by the researcher, are referred to the researcher, or self-select to participate in a study (Stratton 2021). In this instance, individuals were selected in relation to their having worked through all three lockdown periods in the COVID-19 pandemic and were chosen by the researcher, referred to the researcher, or in two instances self-selected having heard about the project. Social distancing rules meant interviews were conducted online during the research period.

Officers were asked:

What has been your experience of working in Lockdown 3?

To what extent has this experience differed (or not) from your previous experiences of Lockdown 1 and 2?

All participants agreed via ethics’ consent forms emailed prior to the interview to being ‘on camera’ and to be recorded during the interview. Recordings were transcribed and analysed initially by manual thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke 2006, 2022) and then followed up in more depth through NVivo. All participants were offered a transcript of the interview. The identities of the forces and police officers were fully anonymised, as was any descriptive information that might result in identification of the police forces or participants.

Online research methods are not new to qualitative researchers. Much has been written prior to the pandemic (see for example, Jenner and Myers 2019; Fielding et al. 2017; Weller 2017; Deakin and Wakefield 2014; Hanna 2012; Bauman 2015) about the efficacy of such work and the benefits and challenges of conducting interviews and other forms of research from a distance. For this project, the benefits of the online interviews conducted in the post-lockdown period were for convenience, ease and breadth of access, low cost (in terms of travel) and potentially higher levels of anonymity (Jenner and Myers 2019, p. 167) because personal information was confined to email addresses.

Participants were able to choose their own space (public or private) in which to conduct the interview and while some researchers identify a lack of rapport as a challenge for such research (see, Weller 2017 and Seitz 2016, for example) this was not the case here. Technical issues, cancellations, lack of shared environment, and disruption of flow due to interruptions—challenges cited by others (see discussion in Jenner and Myers 2019, pp. 164–66 and Seitz 2016) were not deemed problematic for these interviews. We did not find (to the best of our knowledge) that those choosing to speak in a public space were less likely to provide detail and ‘over (or under)-disclose’ than those who were in a private environment (see Jenner and Myers 2019). Although some would argue that face-to-face interviews remain the ‘gold standard’ (Deakin and Wakefield 2014, p. 604), others note that, ‘mediated approaches can generate valuable insight which actually may be richer and more insightful, especially when discussing personal or sensitive topics’ (Howlett 2022, p. 398; see also Jenner and Myers 2019).

4.2. Sample

The sample was diverse and geographically broad. Out of 25 police officers, 14 were male and 11 were female. Twenty-four of the officers identified themselves as sworn, warranted officers while one male participant described himself as Operational Support Staff. One officer was aged over 55. Fourteen officers were aged between 40–55 and ten others were aged between 21–40. Most of the participants had between 5–15 years of service (19), Four had over 25 years of service and only one had less than five years of service. One individual identified as a Superintendent/Chief Superintendent, ten of the participants ranked themselves as Inspector/Chief Inspector, there were nine constables and four sergeants. The Operational Support Staff participant did not have a formal rank. Sixteen participants had dependent children at home, two had elderly/vulnerable people living at home and ten advised they had elderly/vulnerable relatives not living at home (not requiring daily care or supervision).

5. Findings and Discussion

5.1. Foci of Concerns

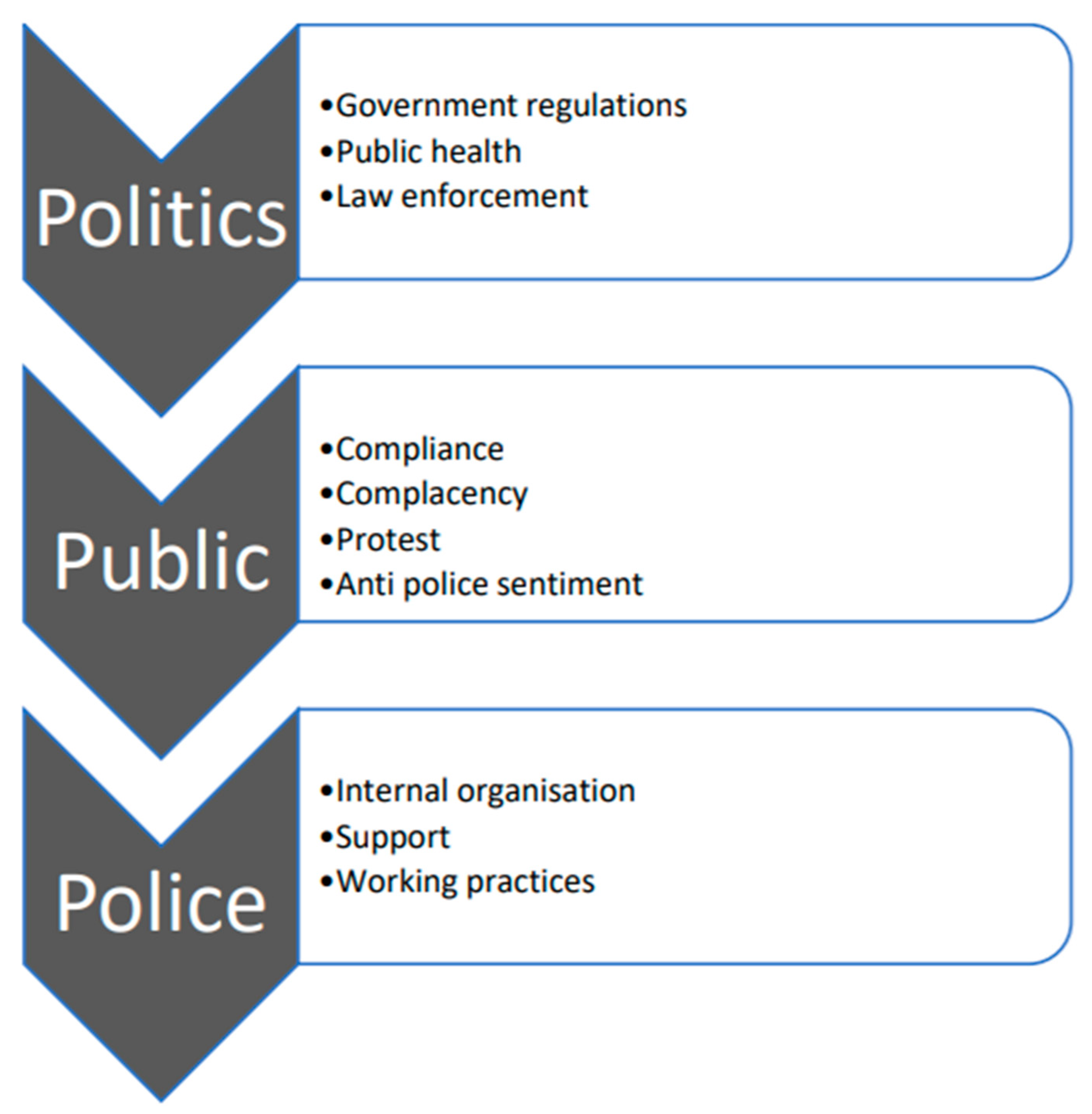

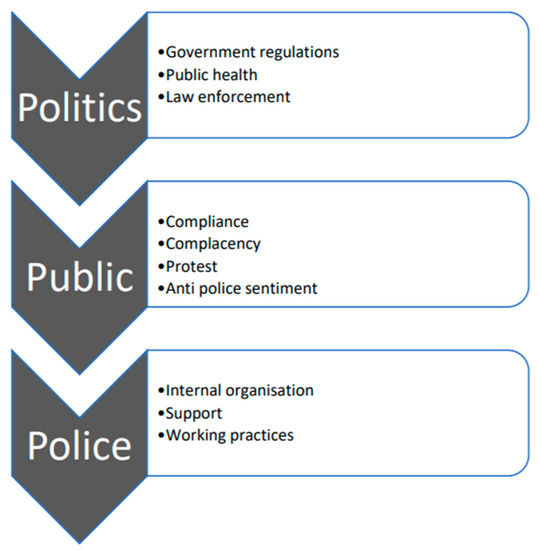

The Nvivo coding of these interviews revealed three main foci of concerns and discussion: a reflection on the politics of the pandemic, public reactions and the responses of their own organisation. The latter observations were largely about their ability to respond professionally to both while maintaining the balance between law enforcement, keeping people safe and sustaining the relationship between themselves and the public. Concerns were held about changing government regulations and tensions inherent in enforcing the restrictions to preserve public health over the three lockdowns. The public foci revealed that officers felt that across the three lockdown periods there was a growing complacency about health and safety, increased protest over the restrictions and a perceptible anti-police sentiment. In terms of the organisations, emergent themes in the interviews covered internal organisation and the perceived support that our respondents received from their respective forces over the lockdown periods.

Figure 1 illustrates the central foci and emergent themes.

Figure 1.

Central foci of concerns.

5.2. Reflections on the Politics

Politics refers largely to the government’s pandemic limiting legislation, which intermittently placed severe restrictions on freedom of movement. The police were placed in the unenviable position of having to respond to the ambiguous messaging and over sixty changes in instructions to the public across the lockdowns (Cairney 2021). The first lockdown was clearly the calmest period for policing the new pandemic legislation across all the ranks of our respondents.

Lockdown one I did find there was a lot of shifts where I’d come in and it was literally like a ghost town.(Constable)

So lockdown one, for the first couple of weeks in my area of business—dead, absolutely dead. Nothing happened.(Inspector)

I think it was easier to police for us in terms of people who were out and about during lockdown one, it was almost a question of why.(Sergeant)

Although, lockdown one was relatively quiet in terms of call outs and the usual daily activity of operational officers, other officers, as Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services (HMICFR) noted (Cairney 2021, p. 4), were busier than ever in their efforts to cover the work of closed government agencies and the courts. Lockdown one was characterised in this study by concerns about ambiguous government directives and ‘difficult to interpret’ legislation. Officers reflecting across all lockdowns almost unanimously noted the confusion around legislation. By lockdown three there was a perceived leniency effect in enforcing the regulations.

We were … almost like a ‘piggy in the middle’ position because we have quite a large and vocal contingent who don’t feel that there should be restrictions on their liberties, which we get, but at the same time we’re under a fair bit of political pressure around ensuring that we’re trying to enforce every element of the legislation.(Inspector)

I think a lot of officers and staff have struggled with … I was going to say the vagueness of the legislation, but I don’t think it’s necessarily the vagueness, it’s the levels of interpretation that comes out of trying to enforce that and the fact that it is so subjective, whether somebody’s excuse for breaching is reasonable or not.(Constable)

Obviously, lockdown three was slightly… I think there was a little bit more leniency in the law with reference to lockdown three.(Constable)

The ambiguity and interpretation of the directives were not the only issues for operational officers, work schedules were continually disrupted by the changing directives:

Yeah, we do shift work and every time the government would make any sort of shift in policy that could result in [railway] stations being flooded by people, they would cancel rest days and get us in to patrol the stations that were flagged as red areas that might see an influx of people.(Constable)

Officers were aware of the pressure this put on their policing by consent mandate by extending their remit and indeed the challenge to democracy itself. The Inspector overseeing her force’s response to COVID-19 felt that being the ‘piggy in the middle’ of the enforcement spectrum was the right place to be and that police had largely succeeded in maintaining the democratic balance. Reflecting over the three lockdown periods, she noted:

Personally, I think we’ve got it reasonably right, because the arguments around us, or the complaints around us not being strong enough and those around us being too heavy-handed are fairly even, which suggests to me that we’ve been somewhere in the middle, so I don’t think we’ve been far off the mark.(Inspector)

Others were not so measured. Looking back across the three lockdown periods, HMICFRS (2021) suggested that ‘the introduction of, and variation to, new legislation and guidance affected the police service’s ability to produce guidance and to brief staff. This inevitably led to some errors or inconsistencies in approach (p. 2). They also documented police frustrations and noted that many forces were frustrated by the way government announcements were communicated. Often forces were not consulted prior to changes in regulations (and this impacted on a force’s ability to collate guidance and brief officers. Forces found it difficult to provide a consistent message, partly because of the complexity of the legislation and regulations and partly by the frequency of changes. They were not given enough time to adjust their responses or messaging in relation to changes. This caused some operational difficulties and created confusion and stress among officers and staff. Such frustrations were mirrored in the public arena.

5.3. Reflections on the Public

The public sphere is illustrated by the relationships between the citizen and the police during a period of restrictions unknown since the Second World War (Cairney 2021). Wagner (2022) observed that during the pandemic the government effectively locked down virtually the whole population, confining people to their homes, banning socialisation, closing places of entertainment and worship, limiting visits to hospitals to see dying relatives and even restricting numbers who could attend funerals. These restrictions enforced by police and guided by ambiguous and confusing legislation and policy updates were in tension with fundamental democratic freedoms (Vasilopoulos et al. 2022). We have noted the context within which the lockdowns in the UK unfolded. Stories of corrupt procurement practices at government level and the media focus particularly on the UK government’s procurement of personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic were sources of irritation to police and the public (Sian and Smyth 2022). Other disclosures about parties in Downing Street and inappropriate meetings between government members, when citizens were required to stay at home, fuelled the discontent and lessened the trust between the public and the police who were seeking to enforce government directives (Davies et al. 2021). The media made much of the fact that there appeared to be one rule for government officials and one for ‘others’ (for example, Weaver 2020). Vasilopoulos et al.’s (2022) empirical study of the public response to the pandemic lockdowns found fear made those who did not trust the government overcome their misgivings and support restrictive measures, whereas feelings of anger had the opposite effect. Anger fuelled distrust, leading cynical citizens to reject the restriction of their liberties. As police continued to enforce the restrictions over time, they were perceived but many sections of the public less benignly.

I would say actually, in the first lockdown, the public relations were better, and we felt appreciated. Since the second and third lockdowns, you’ve seen a gradual eroding of public confidence or public support and, like I say, I think now I would definitely say the first lockdown was a lot more pleasant.(Inspector)

The state of mind our respondents attributed to this change of sentiment was a combination of complacency, anger and boredom.

I think it’s been a theme that’s run all the way through. I think what’s made it harder probably in lockdown three is people’s complacency and the fact that people are just generally fed up with being locked down, and so I think people have been quite creative in their reasonable excuses for being out and about and such like.(Inspector)

During this [third] lockdown I think the general public don’t really care. They’re just going about their business as they normally would and are quite dismissive of officers when they try and speak to them about the whole lockdown situation.(Sergeant)

Some respondents went further and believed there was a real shift towards an anti-police sentiment and that not only was this likely to have a lasting effect but was also affecting police morale:

Just at the start of the last lockdown [second] we did the public order patrols, people were quite happy to come and tell you exactly what they thought, we were pawns of the government, how we should be ashamed or ourselves, et cetera.(Inspector)

It’s definitely getting more and more difficult I think, to police and I think… some people understand that we’re in a very tough situation, but it’s not doing us any favours at the minute in terms of legitimacy.(Inspector)

Jackson and Bradford’s research (Jackson and Bradford 2021) found that compliance dropped across the three lockdowns as the COVID-19 threat diminished overtime. They argue that law enforcement was not a factor or a deterrent, but that people complied to police directives out of a sense of collective harm reduction. Certainly, our findings confirm the diminishing deference to law enforcement across the lockdowns. However, we may speculate that the context within which this was taking place was another factor in what was perceived by many as a deteriorating relationship between the police and the public. A relationship that disturbed many officers:

Policing of protest such as the vigil in memory of Sarah Everard exacerbated this deteriorating situation:

However, then to add to it things like the [Everard] vigil … and seeing politicians saying it was wrong for the police to manhandle women in the park and things like that, without understanding the full picture, I just think it was so damaging of the police reputation and it just makes it even harder for these poor women to come forward to speak to the police.(Sergeant)

Given the strain that the COVID restrictions were having on the public and as a result, the police- public relationship, this put officers in something of a quandary in that the legislation was clearly a factor in the deteriorating relationship, yet it was a tool that enabled them to police and potentially keeping people safe. Few participants wished to keep the legislation beyond its ‘use by’ date:

I don’t want to keep the legislation and things like that. Obviously, it has made policing easier in terms of protests where they’ve got hostile and things like that and the easiest thing for us to do is to go, “Right, we’ll nick you for COVID.”—But I don’t want to keep it.(Acting Sergeant)

The pathway where you could literally go up to everyone and ask them where are you travelling to, why are you travelling, what are you going there? That was great. Now, if COVID’s not an issue anymore and you don’t need to have the pandemic efforts I’m thinking whether keeping those rules might be a bit intrusive now if you don’t have a reason to actually suspect people of doing something wrong, just randomly asking them.(Constable)

It was obvious to most participants that the public were increasingly not ‘in step’ with police on the street:

I’m a big advocate that the police are the public, the public are the police and I just feel that through COVID and the powers we’ve been given under COVID, we’ve lost a lot of kind of middle England [and its] really important that we keep these people on side. When we’ve got to a position where they don’t trust the police, or they don’t want to call the police, we will have some serious public order situations.(Sergeant)

The anti-police sentiment it does get to me, especially kind of in the media and just face-to-face, and I’d say especially recently… and I was going to come onto this a bit later, but I feel like anti-police sentiment is very, very high and it does affect me, it does bother me.(Constable)

This last comment emphasises the police’s discomfort at having to interpret and enforce legislation that not all people felt was justified, and that it was the police themselves who experienced the pushback. Similarly, it is the extension of the protective mandate into health protection that was potentially problematic:

The legitimacy piece has been tricky for policing, and I think police having to deal with a Public Health issue is not something that we’ve had previously. That distinction between policing with consent, the legitimacy of the role we do, the fact that generally people assume we deal with crime, although we don’t, and that civil liberties thing around policing, having to be the perpetrator almost of the government saying, you do this, you do not do that. Police are guardians not warriors and police should be the guardian of the protective democracy rather than the warriors trying to fight with people all the time, and I think this is where this legitimacy piece becomes quite tricky around Public Health and consent, because we are seen as warriors rather than just there to persuade people.(Superintendent)

Over the period of the three lockdowns, there was a distinct shift in public mood from an initial compliance, then as the apparent lethality of the virus receded, there was a measure of complacency. As the restrictions became more irksome, the public started to protest and by lockdown three there was push back against the police in their enforcement duties.

5.4. Reflections on Police Organisation

Participants commented on how their organisation had managed COVID-19 broadly and the extent to which it had concerned itself with officers’ wellbeing. In related research, the authors have reported that during lockdown one, there were problems in issuing PPE to officers and engaging in other protective behaviours, especially in custody (Fleming and Brown 2023). These sentiments were evident from our present respondents too, but several observed over the course of the lockdowns, supplies and protective measures improved greatly:

I think they were a bit slow at the beginning when it first happened, but I think everyone was a bit slow then. They still didn’t know how to react to it and how exactly to handle it. I remember when it first started almost every two days there was a new policy coming into place that didn’t exist the day before. They’d make the policy, but they wouldn’t provide you with the PPE for it and stuff like that. It would be quite delayed. But as the weeks went on they became better at supplying it and managing it.(Constable)

The system within custody has changed massively so ... I won’t say we look quite as togged up as medics in A&E and ICU and the like, but we’re talking overalls and masks and gloves and aprons now and all sorts.(Non-warranted operational officer)

Our previous work on policing the pandemic revealed that in the first two lockdowns front line officers felt they received a good deal of support from their immediate supervisors, reflective of the serving leadership discussed earlier, but that their more senior officers were remote and seemingly unaware of the pressures they were under (Fleming and Brown 2021). Our present sample is a mixture of rank-and-file officers (constables) team leaders (sergeants) and more senior supervisors (inspecting and superintending ranks). Again, on reflection across the three lockdowns there was a noticeable improvement in acknowledging senior management and the force’s efforts to manage communication and the changing environment:

The communication’s been fantastic. Yeah, I’m the first one to… not complain, but I’m the first one to constructively criticise, shall we say, about the [named force] … but I have to say from about… lockdown three, I think the bigger picture is definitely, we’ve been supported, we still get the correct messages and down the chain, my management level has been fantastic.(Constable)

One Inspector observed somewhat ruefully that perhaps more junior officers were not always aware of what had been going on behind the scenes, which may have accounted for earlier criticisms:

We used to be cynical, I think, about the organisation. It’s always, “They’ve done this to us. They haven’t considered this” or whatever. I think part of it is, a lot of people don’t know what the force has actually done or what we’ve tried to do on behalf of staff.(Inspector)

She was my inspector at the start of March last year and because she was the one that said, “You’ve got to go and work from home,” and she knew that I was going to be living on my own and dealing with this, she arranged for one of her staff to call me. He calls me every day just to have somebody to engage with every day.(Constable)

For one married inspector with children, the lockdowns had taught him a lot about flexibility and thinking about the individual needs of staff. A lesson he was determined to take forward:

So I make a point now of only having my sergeant’s meeting in the morning at 9:30 in the morning, purely for that reason because I know that… I’ve only got three part-time sergeants and they all have different caring responsibilities for children, and I know that before 9:30 would cause them quite a lot of stress actually … and so we don’t… our first meeting of the day is 9:30 for that sole reason. And then there’s no pressure.(Inspector)

The empowerment of serving leadership and the cascading effect referred to in the introduction is illustrated by the experience of this superintendent who received a significant amount of support from her line manager:

So, yeah, there’s been no issues at all with any of it, and I even had a conversation about… there was one day I had been in a particular tricky meeting and then I had… I just had to get out. went out on my bicycle for about 20 min, just around the block and I felt really guilty. This was towards the beginning, and I felt really guilty, and we had a discussion around it to say… I said look, this is what I’ve done. He was like, “that’s fine”.(Superintendent)

She in turn supported a sergeant working for her:

I’ve been having a conversation with one of my male sergeants and he’s got his new baby on his lap. You just think, we would never have been in that position even a year ago, and that’s absolutely fantastic. I worry that we will move backwards and I really want us to keep the momentum that this is okay and that we can have a really good operational policing environment where people can work from home.(Superintendent)

6. Conclusions

Previously, the authors’ research (2021; 2022 and 2023) looked specifically at the impact of lockdown one and was informed by a national quantitative survey but which incorporated some qualitative responses. The present research, through a qualitative methodology, took a more local perspective to drill down into the impacts of changing work practices, the challenging relationship with the public, and on wellbeing and working life. From the present analyses, the importance of support from senior leadership (servant leadership) and effective communication over the period of the three lockdowns was emphasized more acutely.

These interviews took place after lockdown three and asked respondents to reflect on to what extent their experience differed from their previous experiences of lockdowns one and two. Without exception, respondents agreed that over the period, they had been exasperated by poor communication about the rules and regulations they were supposed to be policing and the many changes in instructions from the government. This was relatively consistent across the three lockdowns. This was a finding of our earlier research, and this did not change with the current respondents. In reflective mode, officers acknowledged that relationships between senior management and police had improved over the three lockdowns but that dealing with a public unsettled by restrictions to their freedom of movement over time became more difficult and disappointing. All officers are aware of the importance of legitimacy and procedural justice for compliance and by lockdown three that the relationship with the public was perceived to have deteriorated. This placed great strain on the policing by consent mandate.

In lockdown one, all the evidence suggests that officers were more fearful and exercised greater concerns about their own and their family’s wellbeing. This in part was driven by early problems in the issuing of personal protective equipment (PPE) and slowness in instituting other COVID-limiting protections and partly, as with the population in general, they were worried about the impact of COVID-19 on their lives and loved ones. Clearly, by lockdown three these concerns had been significantly alleviated. As the pandemic proceeded over the three lockdowns, police organisations got better at managing communication and adapting to new ways of working, especially supporting those working from home. We have noted elsewhere (Fleming and Brown 2021) that historically, police organisations were resistant to flexible and part-time working, yet the exigencies of the pandemic demonstrated the viability of more agile working practices. As one of the present sample opined:

I think when the advice from the government came out, because police were excluded, they kept us all in, but then someone obviously said, there’s a lot of people in the police who can probably work from home and so I don’t know how those conversations were, but some point, someone obviously came to that decision and said look, if you don’t need to be in the office… I think they actually gave it to supervisors to supervise rather than it coming from the top, saying everyone go home… I think it was “Look, you’re in charge of your department”.(Constable)

Asking officers for their past reflections holds the difficulty of selectively mis- remembering, or emphasizing the negative (or positive). We were reassured by the consistency of our respondents’ commentary and the concordance with our own previous studies (Fleming and Brown 2021) and other research (e.g., Ghaemmaghami et al. 2021; Jackson and Bradford 2021) on officer experience during the pandemic. Whilst our respondents came from a number of different forces in England and Wales, and this may speak to local variations in policing, the police services in question have much in common with respect to structures and remit. The legislation they were required to police was also common.

Overall, the analysis suggests that changing government directives impacted negatively on all aspects of policing. Reflection across the lockdowns has in some ways suggested a more positive organisational climate than reported in earlier research. Examples of service leadership support this finding. At the same time, the perceived relationship between the public and the police has also changed but not positively.

…last year … at Easter we got Easter eggs because [we’re] frontline workers. Everyone was like, “Wow, everyone’s great, you’re doing a great job,” to this now, … there’s a lot of anti-police sentiment out there.(Constable)

In part, it was felt that mixed and constantly changing messaging from the Government made policing more difficult with an increasingly non-compliant public. Although initially there was an understanding by the public that they needed to comply with Government restrictions to stop the spread of the virus and some sympathy for the police as the lockdowns proceeded, the public became bored, angry or complacent about the danger. Police experienced anti-police sentiment in part from the public’s frustrations about being in lockdown, but also latterly from some own goals such as the heavy-handed policing of protest.

For the future, being better prepared and being able to more quickly adapt to the exigencies of an extreme emergency event are crucial to effective policing, as is the need to support officers meeting new demands. Police legitimacy and procedural justice are pivotal to compliance and cooperation. As the Police Foundation (2022, p. 84) noted recently:

We expect this to be a world in which public safety emergencies (linked to extreme weather events, pandemic disease, global conflict, etc.) will arise with increasing frequency. It will be increasingly vital to have in place strong, cooperative working relationships between citizens, communities and the police, as a critical enabler of state efforts to manage and control public behaviour, in the interests of public safety. A reservoir of public trust and willing preparedness to cooperate when crisis strikes, cannot, and should not, be taken for granted. It must instead be understood as an essential part of national and community resilience, requiring up-front investment, strategic preparation, and energetic delivery.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.F. and J.B.; methodology, J.F. and J.B.; software, J.F. and J.B.; validation, J.F. and J.B.; formal analysis, J.F. and J.B.; investigation, J.F. and J.B.; resources, J.F. and J.B.; data curation, J.F. and J.B.; writing—original draft preparation, J.F.; writing—review and editing, J.B.; visualization, J.F. and J.B.; supervision, J.F. and J.B.; project administration, J.F. and J.B.; funding acquisition, J.F. and J.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Southampton in March 2021 ERGO number: 64028.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | See: What makes Britons trust police to enforce the lockdown fairly? | LSE COVID-19, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/COVID19/2020/05/01/what-makes-britons-trust-police-to-enforce-the-lockdown-fairly/ (accessed on 23 December 2022) |

| 2 | The latest available update indicates 118,963 fixed penalty notices (FPNs) were issued over the period of COVID-19 legislation (NPCC 11th Jan 2022) Update on the national police absence rate and Coronavirus FPNs issued by forces in England and Wales (npcc.police.uk). |

| 3 | COVID-19 Related Arrests and Fixed Penalty Notices (FPNs) Issued to Black Individuals | Mayor’s Question Time (london.gov.uk). |

| 4 | We are mindful of Mahony et al.’s (2010, p. 1) observation, that there is no single entity that is ‘the public’ ‘circumscribed by bonds of solidarity and expressing itself in a unified public sphere’. It is taken for granted that the reader will understand that not all ‘publics’’ attitudes to the police changed at this time. |

| 5 | Six police forces in England placed in special measures—BBC News. |

| 6 | Four charged in Bristol https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/dec/09/four-charged-over-damage-to-colston-statue-in-bristol, accessed on 20 December 2020. |

| 7 | The Independent, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/crime/wayne-couzens-convicted-whatsapp-met-police-b2172158.html 2022 (accessed on 23 December 2022). |

| 8 | Met forced to halt ‘absurd’ convictions over vigil, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2022/aug/13/sarah-everard-met-forced-to-halt-absurd-convictions-over-vigil The Observer, 13 August 2022. |

| 9 | Confidence in the police sinks in two years, accessed on 15 March 2022. YouGov. accessed on 8 December 2022. |

| 10 | The Coronavirus Act 2020 and The Health Protection (Coronavirus) Regulations 2020. |

| 11 | The Joint Committee on Human Rights (2021) noted 65 different regulations. |

References

- Aston, Elizabeth V., Megan O’Neill, Yvonne Hail, and Andrew Wooff. 2021. Information sharing in community policing in Europe: Building public confidence. European Journal of Criminology, 14773708211037902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, Antonina. 2015. Qualitative online interviews: Strategies, design, and skills. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal 10: 201–2. [Google Scholar]

- Boehme, Hunter M., Deanna Cann, and Deena A. Isom. 2022. Citizens’ perceptions of over-and under-policing: A look at race, ethnicity, and community characteristics. Crime & Delinquency 68: 123–54. [Google Scholar]

- Boon-Kuo, Louise, Alec Brodie, Jennifer Keene-McCann, Vicki Sentas, and Leanne Weber. 2021. Policing biosecurity: Police enforcement of special measures in New South Wales and Victoria during the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Issues in Criminal Justice 33: 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2022. Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qualitative Psychology 9: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Jennifer, and Jenny Fleming. 2022. Exploration of individual and work-related impacts on police officers and police staff working in support or front-line roles during the UK’s first COVID lockdown. The Police Journal 95: 50–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairney, Paul. 2021. Evidence-informed COVID-19 policy: What problem was the UK Government trying to solve? In Living with Pandemics. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 250–60. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, Louise. 2022. Baroness Casey Review—Interim Report on Misconduct. pp. 1–21. Available online: https://www.met.police.uk/SysSiteAssets/media/downloads/met/about-us/baroness-casey-review/baroness-casey-review-interim-report-on-misconduct.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2022).

- Christensen-Salem, Amanda, Fred O. Walumbwa, Mayowa T. Babalola, Liang Guo, and Everlyne Misati. 2021. A multilevel analysis of the relationship between ethical leadership and ostracism: The roles of relational climate, employee mindfulness, and work unit structure. Journal of Business Ethics 171: 619–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, Ben, Fanny Lalot, Linus Peitz, Maria S. Heering, Hilal Ozkececi, Jacinta Babaian, Kaya Davies Hayon, Jo Broadwood, and Dominic Abrams. 2021. Changes in political trust in Britain during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020: Integrated public opinion evidence and implications. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 8: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deakin, Hannah, and Kelly Wakefield. 2014. Skype interviewing: Reflections of two PhD researchers. Qualitative Research 14: 603–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, Jacqueline M., and Sherri Martin. 2020. Mental health and well-being of police in a health pandemic: Critical issues for police leaders in a post-COVID-19 environment. Journal of Community Safety and Well-Being 5: 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, Nigel G., Raymond M. Lee, and Grant Blank, eds. 2017. The Sage Book of On-Line Research Methods. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, Jenny, and Jennifer Brown. 2021. Policewomen’s Experiences of Working during Lockdown: Results of a Survey with Officers from England and Wales. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice 15: 1977–92. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8195139/ (accessed on 23 December 2022). [CrossRef]

- Fleming, Jenny, and Jennifer Brown. 2022. Staffing the force: Police staff in England and Wales’ experiences of working through a COVID-19 lockdown. Police Practice and Research 23: 236–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, Jenny, and Jennifer Brown. 2023. The Impact of changing working patterns for police personnel in England and Wales during COVID-19 lockdown one. In Handbook of ‘Policing within a Crisis’. Edited by Wright Martin and Cordener Gary. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel, Marie Ottilie, Laura Giessing, Sebastian Egger-Lampl, Vana Hutter, Raoul R. D. Oudejans, Lisanne Kleygrewe, Emma Jaspaert, and Henning Plessner. 2021. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on European police officers: Stress, demands, and coping resources. Journal of criminal Justice 72: 101756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaemmaghami, Aram, Rob Inkpen, Sarah Charman, Camille Ilett, Stephanie Bennett, Paul Smith, and Geoff Newiss. 2021. Responding to the public during a pandemic: Perceptions of ‘satisfactory’ and ‘unsatisfactory’ policing. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice 15: 2310–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, Paul. 2012. Using internet technologies (such as Skype) as a research medium: A research note. Qualitative Research 12: 239–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HMICFRS. 2021. Policing the Pandemic. The Police Response to the Coronavirus during Pandemic 2020. Accessed at: Policing in the Pandemic—The Police Response to the Coronavirus Pandemic during 2020—HMICFRS. Available online: https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmicfrs/publications/the-police-response-to-the-coronavirus-pandemic-during-2020/ (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- Hough, Mike, Jon Jackson, and Ben Bradford. 2017. Policing, procedural justice and prevention. In Handbook of Crime Prevention and Community Safety. London: Abingdon, pp. 274–93. [Google Scholar]

- Howlett, Marnie. 2022. Looking at the ‘field’ through a Zoom lens: Methodological reflections on conducting online research during a global pandemic. Qualitative Research 22: 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, Jonathan, and Ben Bradford. 2021. Us and Them: On the Motivational Force of Formal and Informal Lockdown Rules. LSE Public Policy Review 1: 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenner, Brandy M., and Kit C. Myers. 2019. Intimacy, rapport, and exceptional disclosure: A comparison of in-person and mediated interview contexts. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 22: 165–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kniffin, Kevin M., Jayanth Narayanan, Frederik Anseel, John Antonakis, Susan P. Ashford, Arnold B. Bakker, Peter Bamberger, Hari Bapuji, Devasheesh P. Bhave, Virginia K. Choi, and et al. 2021. COVID-19 and the workplace: Implications, issues, and insights for future research and action. American Psychologist 76: 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyprianides, Arabella, Ben Bradford, Marcus Beale, Leanne Savigar-Shaw, Clifford Stott, and Matt Radburn. 2022. Policing the COVID-19 pandemic: Police officer well-being and commitment to democratic modes of policing. Policing and Society 32: 504–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufs, Julian, and Zoha Waseem. 2020. Policing in Pandemics: A Systematic Review and Best Practices for Police Response to COVID-19. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 51: 101812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loader, Ian. 2016. In search of civic policing: Recasting the ‘Peelian’ principles. Criminal Law and Philosophy 10: 427–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahony, Nick, Newman Janet, and Barnett Clive. 2010. Rethinking the Public’ in Mahony. In Rethinking the Public: Innovations in Research, Theory and Politics. Edited by Mahony Nick and Newman Janet. Bristol: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mehdizadeh, Shahin, and Katy Kamkar. 2020. COVID-19 and the impact on police services. Journal of Community Safety and Well-Being 5: 42–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, Freya, Charles Symons, and Holly Carter. 2021. Exploring the Role of Enforcement in Promoting Adherence with Protective Behaviours During COVID-19. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newiss, Geoff, Sarah Charman, Camille Ilett, Stephanie Bennett, Aram Ghaemmaghami, Paul Smith, and Robert Inkpen. 2022. Taking the strain? Police well-being in the COVID-19 era. The Police Journal 95: 88–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papazoglou, Konstantinos, Daniel M. Blumberg, Michael D. Schlosser, and Peter I. Collins. 2020. Policing during COVID-19: Another day, another crisis. Journal of Community Safety and Well-Being 5: 39–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Police Foundation. 2022. Redesigning Policing and Public Safety in the 21st Century. London: The Police Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Ralph, Liam, Matthew Jones, Michael Rowe, and Andrew Millie. 2022. Maintaining police-citizen relations on social media during the COVID-19 pandemic. Policing and Society 32: 764–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, Misbah. 2020. Policing in pandemic: Is perception of workload causing work–family conflict, job dissatisfaction and job stress? Journal of Public Affairs 22: e2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargeant, Elise, Molly McCarthy, Harley Williamson, and Kristina Murphy. 2022. Empowering the police during COVID-19: How do normative and instrumental factors impact public willingness to support expanded police powers? Criminology & Criminal Justice, 17488958221094981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, Sally. 2016. Pixilated partnerships, overcoming obstacles in qualitative interviews via Skype: A research note. Qualitative Research 16: 229–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sian, Supreme, and Stewart Smyth. 2022. Supreme emergencies and public accountability: The case of procurement in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 35: 146–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, Rylan, and Ryan Sandrin. 2022. The use of personal protective equipment (PPE) by police during a public health crisis: An experimental test of public perception. Journal of Experimental Criminology 18: 297–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stogner, John, Bryan Lee Miller, and Kyle McLean. 2020. Police stress, mental health, and resiliency during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Journal of Criminal Justice 45: 718–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stott, Clifford, Matt Radburn, Geoff Pearson, Arabella Kyprianides, Mark Harrison, and David Rowlands. 2022. Police powers and public assemblies: Learning from the Clapham Common ‘Vigil’during the COVID-19 pandemic. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice 16: 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratton, Samuel J. 2021. Population Research: Convenience Sampling Strategies. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine 36: 373–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Joint Committee on Human Rights. 2021. The [UK’s] Government Response to Covid-19 Fixed Penalty Notices. Fourteenth Report of Session 2019-21. HC 1364/HL Paper 272. Available online: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/jt5802/jtselect/jtrights/545/54502.htm (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- Thompson, Danielle E., Debra Langan, and Carrie B. Sanders. 2022. Policemen, COVID-19, and police culture: Navigating the pandemic with colleagues, the public, and family. Policing and Society, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilopoulos, Pavlos, Haley McAvay, Sylvain Brouard, and Martial Foucault. 2022. Emotions, governmental trust and support for the restriction of civil liberties during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Political Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, Anne. 2022. Emergency State; How We Lost Freedoms in the Pandemic and Why. Harmondsworth: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Waters, IIan. 1996. Quality of service: Politics or paradigm shift? In Core Issues in Policing. Edited by Leishman Frank, Loveday Barry and Savage Steve. Harlow: Longman, pp. 205–17. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, Matthew. 2020. Pressure on Dominic Cummings to Quit over Lockdown Breach. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2020/may/22/dominic-cummings-durham-trip-coronavirus-lockdown (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Weller, Susie. 2017. Using internet video calls in qualitative (longitudinal) interviews: Some implications for rapport. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 20: 613–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).