1. Introduction

Repatriation has emerged as a popular study topic among scholars and academics in recent decades. Studies frequently examined readjustment and its interactions with other in-country aspects, such as job roles (clarity, discretion, novelty, and conflict) in employment contexts that can affect adjustment efficacy (

James 2020). Despite the growth and successes of repatriation studies, room for improvement exists (

Ellis et al. 2020). Due to the costs and potential negative implications of expatriation, in-depth investigations are required on this topic. Previous studies on repatriation highlighted the issues and challenges during adjustment linked to the work environment, including organizational support and career planning.

Ineffective repatriation is a major contributor to high turnover rates among repatriates, ranging between 20% and 50% within the first year of return (

Paik et al. 2002). Work environment factors, including human-resource-controlled factors related to job and career planning, contribute to ineffective repatriation (

Sulaymonov 2017). The financial and strategic costs of employee turnover are considerable in organizations (

Aldossari and Robertson 2016;

Naude and Vögel 2018;

Gaio Santos and Martins 2019). Thus, exploring the association between repatriation and work environment factors helps address turnover among repatriates and the loss faced by organizations.

Research on repatriation has mostly focused on the Western and Eastern nations. Less attention has been paid to the Middle East, including the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) (

Alawi 2020). Surprisingly, no comparative study has been undertaken among repatriated students in GCC nations, including Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Oman, and Qatar. According to

Alawi (

2020), “no previous information on the experiences of GCC repatriates and their opinions of the working environment in the GCC after completing their overseas experience has been documented or published”. Since 2005, the GCC countries have sent an estimated 170,000 students to universities in America, Europe, Asia, Australia, and New Zealand (

Puri-Mirza 2020).

As prior studies exhibited that the number of GCC outbound students is substantial, repatriated students and their adjustment challenges, particularly in the work environment, should be examined and improved. Nevertheless, research on the labor market in the GCC (

Bokhari 2020;

Almahamid and Ayoub 2022;

Al-Asfour et al. 2022) revealed that outbound students from the GCC prefer and continue to pursue degrees that do not correlate with their labor market demands, making research on repatriates’ adjustment to work environment a realistic option.

A scarcity of empirical research exists on organizational assistance and career planning among repatriates in the GCC.

Allen and Alvarez (

1998) and

Swaak (

1995) argued that effective repatriation requires assisting expatriates upon their return. The returnees should be appreciated and considered investments to reduce possible turnovers and preserve their knowledge and skills.

Swaak (

1995) noted that the failure to “appreciate” repatriates is a critical problem for human resource (HR) managers handling repatriation. Thus, this study investigated repatriates’ experiences during their adjustment to work environments in the GCC region by employing career ambition as a mediator and career expectation as a moderator. The study aimed to provide insights to organizations and repatriates by broadening the current theoretical and empirical understanding.

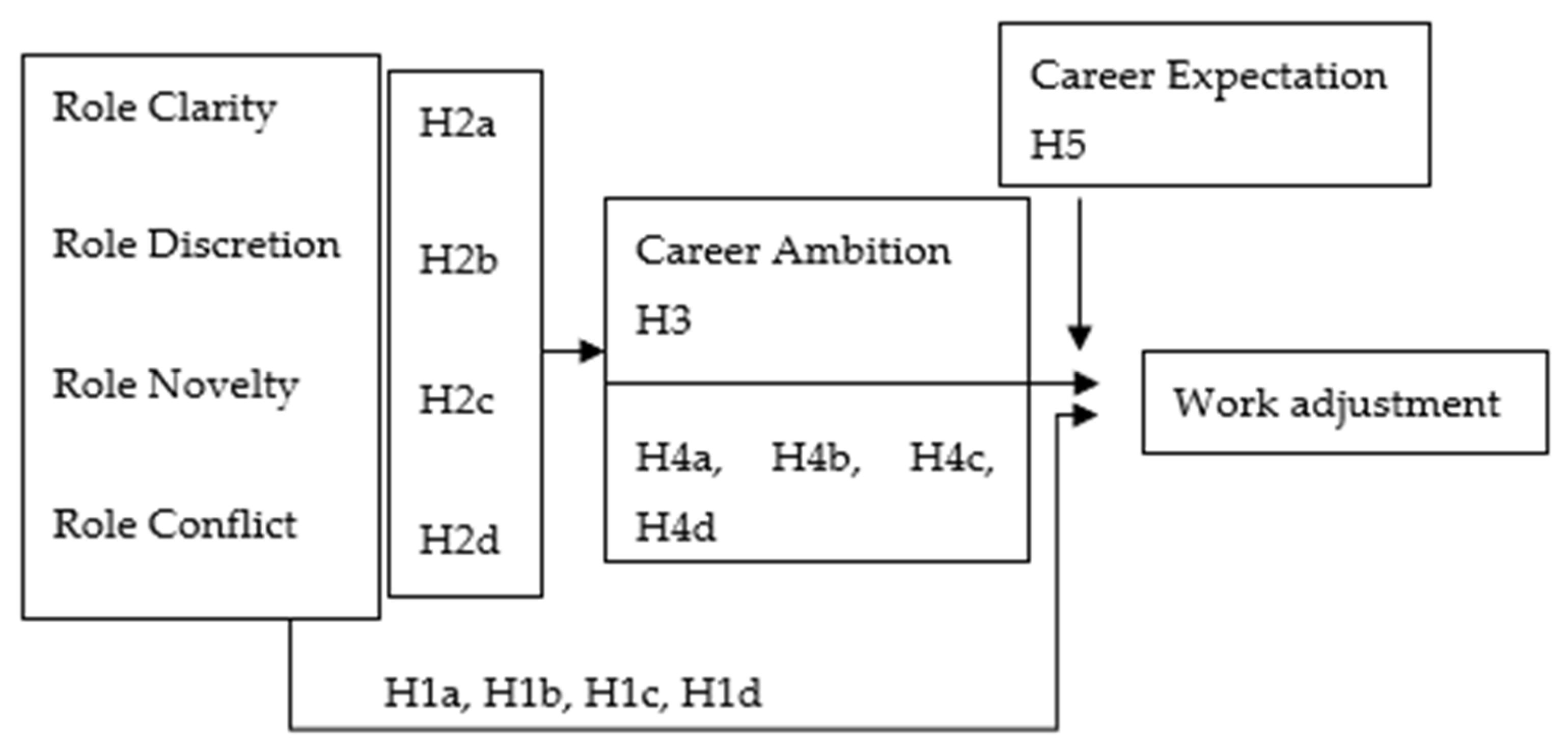

In addition, this study attempted to fill the knowledge gap on repatriates adapting to employment by providing sufficient empirical data. This study also contributed to the body of knowledge by evaluating how career-ambitious returning students in the GCC adjust to their job roles in their work environment. Finally, this study offered recommendations for additional research in this area and several practical suggestions. This study advanced the understanding of human resource management practices by examining organizational job roles in the GCC that can affect work transition and impact repatriates’ work adjustment outcomes. Understanding repatriates’ ambitions during the transition to work in the GCC is vital to avoiding work adjustment challenges and issues. Therefore, the study’s findings may help guide regional HR practitioners. As a result of the preceding discussion, the current study addressed the following questions:

Do the GCC student repatriates’ job dimensions (role clarity, role discretion, role novelty, and role conflict) significantly influence their work adjustment in the GCC?

Do the GCC student repatriates’ job dimensions (role clarity, role discretion, role novelty, and role conflict) significantly influence their career ambitions in the GCC?

Does career ambition positively affect student repatriates’ work adjustment process in the GCC?

Does career ambition mediate the relationship between student repatriates’ job roles (role clarity, role discretion, role novelty, and role conflict) and their work adjustment in the GCC?

Does career expectation among student repatriates moderate the relationship between career ambition and their work adjustment in the GCC?

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Approach

Purposive sampling is used in this study to choose respondents based on nonprobability. This decision was made to guarantee that the data collected are representative and have good quality. Purposive sampling is the process of selecting people who have enough expertise and experience with the subject to offer the necessary information (

Janes 2001). An online survey method was used as the research technique since it is a commonly used method worldwide that enables the collection of broad-level data from the target population. Compared with other methodologies, the cost of data collection is extremely low, and faster results are obtained using the online survey method (

Rasool et al. 2022).

3.2. Instrument Designing

A designed questionnaire was developed for data collection in this study. Hypotheses were developed when a literature review was undertaken to build the study’s foundation. As the targeted respondents in this study were student repatriates from the GCC who internationally studied, the survey was undertaken in English. A pilot study was conducted to validate the instrument’s methodological accuracy to guarantee that the respondents understood the questions. Twenty participants from the GCC region were included in the pilot study (involving Ph.D. students, associate professors, full professors, HR managers, and career advisors). The participants were informed of the study’s topic. After the instrument was validated, it was distributed to the targeted respondents to gather data. A total of 317 completed responses were subsequently gathered in this study.

3.3. Variables Measurements

A survey method was used in a cross-sectional descriptive analysis. A total of 34 items were adapted and assessed based on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree), refer to

Appendix A.

Table 1 shows the number of items, sample items, and the source according to the variables.

3.4. Sample and Data Collection

The online survey was electronically distributed through Google Form. Responses from 317 respondents were received. Data were gathered from the Saudi students’ club in Australia, the Ministry of Education in Kuwait, and a Gulf job search company in Bahrain. The first author contacted these groups and provided them with survey letters through emails. They were supportive and responded to our enquiries. Saudi students’ club in Melbourne, Australia, distributed the survey through their alums’ social media groups, which generated most of the survey responses. We were supported in publicizing the survey by an employee of the Kuwaiti Ministry of Education’s Department of Authentication, who oversaw ratifying internationally obtained qualifications. Additionally, Gulf Job Search in Bahrain, a company that conducts surveys and market research through paid services, was contacted. They distributed the survey across different GCC countries’ platforms, with a decent number of respondents returning completed surveys. The survey link contained simple steps for completion. Initial participating qualifications were included in the screening questions to ensure that the respondent fit the sample criteria.

3.5. Demographics

Respondents in this study were student repatriates who had lived and studied abroad for a minimum of one year. They were GCC nationals of both sexes, employees working in both the public and private sectors. They comprised 40.1% men and 59.9% women. Their nationalities included Bahrain (16.7%), Kuwait (15.1%), Oman (15.1%), Qatar (18.9%), Saudi Arabia (22.1%), and the UAE (12%). The length of their overseas stay was in the range of 1–5 years (80.7%), 6–10 years (13.6%), 11–15 years (5.4%), and more than 15 years (0.3%). All the respondents had working experience of more than 12 months (100%).

4. Results

A descriptive analysis was undertaken on the responses before evaluating the measurement and structural models. To examine the direct and indirect correlations, structural equation modeling (SEM), Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS), and Smart PLS 3.0 were used.

Hair et al. (

2014) suggested that when the study is focused on evaluating a theoretical framework from a prediction standpoint, PLS-SEM is considerably more suited. After estimating the path estimates in the structural model, a bootstrap analysis was used to measure the statistical significance of the path coefficient.

Chin (

1998) advocated 5000 resamplings when operating bootstrapping to estimate a parameter. Therefore, in this study, bootstrapping procedures with 5000 resamplings were used. Moreover, the mean values of the variables were calculated.

Table 2 indicates that the mean values of the variables were higher than the median value of the Likert scale for all measurements.

4.1. Common Method Variance

Scale items were all subjected to exploratory-factor-analysis (EFA) conditions using unrotated principal component analysis. None of the conditions was applicable. At the end of the analysis, all factors were found to have obtained eigenvalues greater than one. All factors explained 65.50% of the variance. The first factor could only explain 26.20% of the variance. These findings prove that common method bias was not an issue in this study.

4.2. Reliability and Validity

Construct validity determines if the measurements properly measure the target construct using both convergent and discriminant validity (

Sekaran and Bougie 2016). To determine the degree of validity, a loading value of more than 0.50 is recommended, with values of 0.70 and above appropriate for a single indication (

Hair et al. 2014). A loading value of 0.50 or less suggests that the indication is invalid and should be ignored (

Hidayanto et al. 2014;

Marcoulides 1998). In this study, a 0.5 loading cutoff value was utilized. The results of the analysis of the factor loading revealed that the constructs surpassed the minimum cutoff point of 0.50 (see

Table 3).

4.3. Convergent Validity

The degree of correlation between measurements within a single construct is determined by convergent validity (

Sekaran and Bougie 2016). Factor loading indicators, average variance extracted (AVE), and composite reliability (CR) should all be used to determine convergent validity (

Hair et al. 2014). The AVE (mean-variance extracted for items loaded on a construct) was greater than or equal to 0.5. The AVE of all the constructs should satisfy the specified cutoff value. The study’s findings indicated a CR range of 0.89 to 0.99, which was higher than the cutoff value of 0.7.

Table 3 shows the values of the constructs.

4.4. Discriminant Validity

Discriminant validity recommends the degree to which measures of different latent variables are distinctive. For example, the variance in the measure should reflect only the variance attributable to its intended latent variable and not to other latent variables (

O’Leary-Kelly and Vokurka 1998). According to

Gefen and Straub (

2005), discriminant validity is demonstrated when

- (1)

The measurement items’ loading patterns are appropriate, with the measurement items substantially loading on their theoretically specified component but not on other factors;

- (2)

Each factor’s square root of AVE is higher than any pair of its correlations with any other component.

In this study, all the measurement items had suitable pattern loadings. Each item loaded higher on its major construct than other constructs. The

Fornell and Larcker (

1981) criterion was also utilized to check for discriminant validity. The criterion states that the average variance shared between each construct and its measures must be larger than the variance shared between the construct and other constructs. The findings are presented in

Table 4.

The heterotrait–monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT) was established by

Henseler et al. (

2015) to validate discriminant validity. Henseler and his colleagues conducted simulations to show that standard criteria such as the Fornell and Larcker criterion, as well as cross-loadings, are ineffective in determining discriminant validity. As a result, HTMT can more accurately measure discriminant validity. If the HTMT score is less than 0.90, discriminant validity between the two conceptions has been demonstrated. Therefore, this study utilized the HTMT criteria to further check the discriminant validity concerns. The correlation for each construct was smaller than the square root of the average variance retrieved by the indicators assessing the constructs, as shown in (

Table 5), indicating satisfactory discriminant validity. All values in the table are below 0.90, demonstrating that discriminant validity has been established.

4.5. Variance Explained (R2)

According to

Hair et al. (

2014), the main assessment test for the goodness of the structural pattern in PLS is the beta value of the

R2, determination coefficient, and path coefficient significance levels.

Cohen’s (

1988) recommended values for

R2 are as follows: 0.02–0.12 weak, 0.13–0.25 moderate, and 0.26 above substantial. In this study, the

R2 value for career ambition in the endogenous construct was 0.119, which suggests that exogenous variables describe 11.9 per cent variance on career ambition. The

R2 value for work adjustment in the endogenous construct was 0.10, which suggests that exogenous variables describe 10 per cent variance on work adjustment.

Table 6 presents the values of variance explained.

4.6. Effect Size

The study calculated the impact of all factors.

Sullivan and Feinn (

2012) argued that the study results should be recorded with statistical validity (

p-value) as well as analytical relevance.

Hair et al. (

2014) suggested that change in

R2 should be considered when a model is omitted to calculate the impact (

f2) of an exogenous variable that explains the substantial impact on endogenous variables of the omitted variable. Commonly used guidelines for effect size were given by

Cohen (

1988), which are 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 representing small, medium, and large effects, respectively.

Hair et al. (

2014) concluded that the low effect size of the variable does not imply that the variable is not negligible. The effect size of all the exogenous study variables is shown in

Table 7 below.

4.7. Predictive Relevance of the Structural Model

Hair et al. (

2014) suggested that the predictive relevance of a structural model is established if the above Q

2 value for the dependent variables in all the hypothesized relationships is greater than zero. The predictive relevance of the proposed structural model is determined through blindfolding procedure by using the cross-validated redundancy technique in Smart-PLS (version 3.0). The findings of this study have established the predictive relevance of the proposed structural model as the Q

2 values for the dependent variables in the hypothesized relationships are greater than zero. The results are given in

Table 8.

4.8. Structural Model Assessment

Structural model evaluation is validated by reporting the path coefficient, standard errors,

t-value,

p-value, coefficient of determination (

R2), effect size, and predictive relevance in the second, third, fourth, and fifth steps (

Hair et al. 2020).

Table 9,

Table 10,

Table 11 and

Table 12 depict direct and indirect effects.

4.9. Direct Effect Testing

Table 9 depicts that H1a (role clarity -> work adjustment), H1c (role novelty -> work adjustment), and H1d (role novelty -> work adjustment) are supported (β = 0.252,

t = 3.463,

p < 0.000; β = 0.115,

t = 2.122,

p < 0.017; and β = 0.218,

t = 3.791,

p < 0.00, respectively). H1b (role discretion -> work adjustment) is rejected (β = −0.032,

t = 0.441,

p < 0.330). Therefore, this study confirmed that there is a positive relationship between role clarity (H1a) and work adjustment. Role novelty (H1c) and role conflict (H1d) both supported the hypotheses that they have negative relationships with work adjustment. Role discretion (H1b) shows a negative correlation with work adjustment, and the hypothesis was not supported.

Table 9.

Direct Hypotheses Results.

Table 9.

Direct Hypotheses Results.

| Hyp | Path | Beta | Std Error | T Values | p Values | Decision |

|---|

| H1a | RC -> WA | 0.252 | 0.073 | 3.463 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H1b | RD -> WA | −0.032 | 0.073 | 0.441 | 0.330 | Not supported |

| H1c | RN -> WA | 0.115 | 0.054 | 2.122 | 0.017 | Supported |

| H1d | RC -> WA | 0.218 | 0.057 | 3.791 | 0.000 | Supported |

Table 10 depicts that H2a (role clarity -> career ambition), H2c (role novelty -> career ambition), and H2d (role novelty -> career ambition) are supported (β = 0.252,

t = 3.463,

p < 0.000; β = 0.115,

t = 2.122,

p < 0.017; and β = 0.218,

t = 3.791,

p < 0.00, respectively). H1b (role discretion -> career ambition) is rejected (β = −0.032,

t = 0.441,

p < 0.330). As a result, this study showed that there is a positive correlation between role clarity (H1a) and career ambition. The hypotheses that role novelty (H1c) and role conflict (H1d) have negative correlations with career ambition were both validated. Role discretion showed a negative association with career ambition, and the hypothesis (H1b) was not supported.

Table 10.

Direct Hypotheses Results.

Table 10.

Direct Hypotheses Results.

| Hyp | Path | Beta | Std Error | T Values | p Values | Decision |

|---|

| H2a | RC -> CA | 0.252 | 0.073 | 3.463 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2b | RD -> CA | −0.032 | 0.073 | 0.441 | 0.330 | Not supported |

| H2c | RN -> CA | 0.115 | 0.054 | 2.122 | 0.017 | Supported |

| H2d | RC -> CA | 0.218 | 0.057 | 3.791 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3 | CA -> WA | 0.256 | 0.052 | 4.918 | 0.000 | Supported |

H3 (career ambition -> work adjustment) is supported (β = 0.256, t = 4.918, p < 0.000). Therefore, this study showed that there is a positive correlation between career ambition and work adjustment.

4.10. Mediating Effect Testing

In this analysis, we adhered to the guidelines of

Zhao et al. (

2010) and applied bootstrapping measurements in SEM. The calculated bootstrap

t-statistic value was computed based on the following formula:

Table 11 depicts that H2a (role clarity -> career ambition -> work adjustment), H2c (role novelty -> career ambition -> work adjustment), and H2d (role conflict -> career ambition -> work adjustment) are supported (β = 0.065,

t = 2.608,

p < 0.005; β = 0.029,

t = 1.839,

p < 0.033; and β = 0.056,

t = 2.997,

p < 0.01, respectively). H2b (role discretion -> career ambition -> work adjustment) is rejected (β = −0.008,

t = 0.426,

p < 0.335). Therefore, this study confirmed that career ambition mediated the relationship between role clarity (H2a), role novelty (H2c), role conflict (H2d), and work adjustment. Career ambition did not mediate the link between role discretion (H2b) and work adjustment.

Table 11.

Mediation Hypotheses Results.

Table 11.

Mediation Hypotheses Results.

| Hyp | Path | Beta | Std Error | T Values | p Values | Decision |

|---|

| H4a | RC -> CA -> WA | 0.065 | 0.025 | 2.608 | 0.005 | Supported |

| H4b | RD -> CA -> WA | −0.008 | 0.019 | 0.426 | 0.335 | Not supported |

| H4c | RN -> CA -> WA | 0.029 | 0.016 | 1.839 | 0.033 | Supported |

| H4d | RC -> CA -> WA | 0.056 | 0.019 | 2.997 | 0.001 | Supported |

4.11. Moderating Effect Testing

Table 12 depicts that H5 (career ambition -> career expectation -> work adjustment) is supported (β = 0.139,

t = 3.051,

p < 0.001). Therefore, this study confirmed that career expectation moderated the relationship between career ambition and work adjustment.

Table 12.

Moderation Hypothesis Results.

Table 12.

Moderation Hypothesis Results.

| Hyp | Path | Beta | Std Error | T Values | p Values | Decision |

|---|

| H5 | CA * CE -> WA | 0.139 | 0.046 | 3.051 | 0.001 | Supported |

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study examined the relationships between job roles, career ambition, career expectation, and work adjustment on GCC repatriates who have been working for more than 12 months since their return. The results demonstrated that H1b, H2b, and H4b were not supported. As predicted, career ambition was found to mediate variables and repatriates’ work adjustment in the three accepted hypotheses. Career expectation considerably moderated career ambition and work adjustment. Similarly, the link between role clarity and work adjustment was statistically significant. Previous studies by

Black and Gregersen (

1991) and

Paik et al. (

2002) indicated that repatriates with role clarity in their job roles adjust to work more easily than those with little or no clarity.

Suutari and Välimaa (

2002) emphasized that role clarity significantly influences repatriates’ work adjustment.

The study’s findings support prior research, which argued that clarity among job roles plays a significant part in facilitating work adjustment since it lowers ambiguities and uncertainties. When high clarity exists in work positions, employees may use their talents and expertise to establish trust in themselves. Therefore, role clarities in the workplace environment in the GCC show that employed repatriates have enjoyed considerable levels of role clarities. Unfortunately, the hypothesis of role discretion and job adjustment was rejected.

James (

2019) emphasized that the loss of choices at work might negatively impact repatriates’ transition to employment for different reasons, including the lack of organizational support. The limited choices might have impacted the GCC work environment. Organizational managers or supervisors may have given their staff little discretion, or there may be misfits among the employees who were unqualified for the roles. The findings support the studies of

Almahamid and Ayoub (

2022) and

Al-Asfour et al. (

2022). They highlighted that outbound students from the GCC sought qualifications that did not reflect their local market needs and avoided employment in the private sector. Furthermore, a large portion of the unqualified graduates is hired in the public sector to reduce unemployment.

The relationship between job novelty and work adjustment was negatively significant in this study. The negative association might be attributed to inadequate working conditions in the GCC. This finding is consistent with earlier studies by

Suutari and Välimaa (

2002) and

James (

2020). Resultantly, repatriates might have encountered inconsistent managerial practices and a lack of workplace organizational support. Other causes for this negative correlation might include the lack of essential abilities for the positions and unique organizational functions.

A significantly negative relationship exists between role conflict and work adjustment. This finding is congruent with earlier studies by

Black (

1994),

Suutari and Välimaa (

2002), and

James (

2020). The significant relationship might have resulted from the lack of organizational knowledge on employees’ abilities obtained from other workplaces and sophisticated place modeling that differed from existing operational norms in GCC workplaces.

Role clarity and career ambition correlation were also significant. The present study’s findings report gaps in the literature as it provided and demonstrated associations between variables from job roles and career ambition in adjusting to work environments.

El Baroudi et al. (

2017) studied ambition from a career development perspective. They believed that career ambition as an internal motivational process leads to success if correctly utilized. Career ambition was also found to tackle most abstracts and general dispositions in their study. The correlated relationship might have resulted from defined goals and clear work purposes among repatriates, encouraging them to adjust to their work environments. Career ambition might have driven GCC repatriates’ actions by channeling and inspiring them to satisfy their work purposes. Combining both factors might increase work adjustment facilitation by clearly acknowledging how to recognize work principles.

The effect size of role discretion and career ambition was small, which might be caused by misfits of employees, managers, or supervisors. Misfits can impact discretions in the work environment (

Suutari and Välimaa 2002). There is a possibility of low or absence of role discretion in the GCC work environment, which results in the insignificant relationship between role discretion and career ambition. Research on labor markets in the GCC revealed that individuals from the region obtain unnecessary qualifications that do not reflect market needs (

Nair 2017). The mismatch between the market requirements and acquired qualifications might have contributed to the findings. Discretionary roles within the work environment and GCC organizations cause doubts due to misfits or the disappearance of merits that might have contributed to the low correlation between role discretion and career ambition.

The effect size of role conflict and career ambition was large possibly because organizations or managers may have misunderstood new techniques or their employees’ skills; employees might have learned different work practices and views to undertake their work tasks. Other potential reasons could be organizational controlling practices that GCC countries commonly implement (

Nair 2017) or the lack of training and development programs. In previous studies by

Black (

1994) and

Suutari and Välimaa (

2002), role conflict was found to impede work adjustment among repatriates.

The effect size of role novelty and career ambition was also large potentially due to the inadequate work environment in the GCC. Employees examined in this study might have confronted role novelty issues in their work environment that contradicted their skills, knowledge, or the lack of enough information. Bad management practices and the lack of organizational support could impact career ambitions, causing discouragement among the employees. The impacts can limit employees’ performances and disrupt behaviors, affecting their ambitions. Nevertheless, correlations between other factors such as insufficient job skills, organizational culture, and the lack of support have been previously studied in the context of the GCC region.

Almahamid and Ayoub (

2022),

Al-Asfour et al. (

2022), and

Nair (

2017) highlighted that a substantial number of GCC students qualified abroad had sought qualifications that did not reflect market needs, which caused low productivity, overstaffing, avoidance of employment in the private sector, lower-paid employment, and distortion in the education system in preparation for careers in the public sector. On the other hand, employees might be inexperienced in undertaking work roles and tasks that could affect their career ambitions.

Career ambition’s effect was found to mediate the association between job roles (clarity, novelty, and conflict) and work adjustment among GCC repatriates. Obvious expectations such as compensation and income, operating hours, tasks and obligations, and rules and regulations could have led to this issue. Higher career development chances are associated with entering the workforce directly after education, which would be a reasonable cause for such an outcome. Studies by

Bui et al. (

2021),

Ćurić Dražić et al. (

2018), and

El Baroudi et al. (

2017) provide evidence that career ambition is a source of goal setting and readiness to take on extra duties for an organization. Nevertheless, as anticipated, the correlation between role discretion and career ambition was not supported. Role discretion in the GCC work environments did not significantly impact career ambitious repatriates’ work adjustment. Role discretion was either limited or not permitted to employees due to misfits by their managers or supervisors within the GCC work environment, contributing to the hindrance of work adjustment. In this case, misfits can make individuals indeterminate in their work environment, reducing repatriation career ambitions toward work adjustment.

Furthermore, novelties in job roles within organizations would be challenging for ambitious repatriates to pursue their targets. In turn, adding challenges to their job roles influences their performance, reduces motivational factors, and develops negative attitudes, thereby becoming more likely to be unsatisfied and diminishing their career ambitions. Therefore, understanding their work development and career progress loses importance toward work adjustment. Concurrently, conflicting job roles within workplaces would make it difficult for ambitious repatriates to achieve their goals and result in dissatisfaction.

This study demonstrated that career ambition significantly mediated the accepted hypotheses in repatriates’ work adjustment. The literature on repatriates’ work adjustment perspective lacks career ambition studies. Thus, this study’s findings can be the basis for in-depth future studies. Nevertheless, among GCC students, this study revealed that the effect of career ambition on the role (clarity, novelty, and conflict) is a predictor of repatriates’ work adjustment. In the current study, career expectation moderated between career ambition and work adjustment possibly due to GCC repatriates successfully securing employment positions to earn desired incomes, plan their careers, and work toward achieving their targets. The literature on career expectations is associated with forecasts and anticipation of all career aspects (

Hurst and Good 2009;

Balc and Bozkurt 2013;

Liu et al. 2019). Lastly, findings from the study’s hypotheses framework and correlation results confirm the projected positive link between career ambition and career expectation and their effect on work adjustment. The observed data collectively confirm the notion that career ambition has either a positive or negative relationship with work adjustment in the GCC environment. This study’s findings have further expanded the understanding of the robustness of career expectation and its effect on predicting work adjustment among repatriates.