1. Introduction

The business and society nexus in relation to social responsibility has been identified and studied in the literature using numerous terms, including sustainability, creating shared value (CSV), corporate social innovation (CSI), stakeholder management, corporate citizenship, and corporate social performance. The term chosen in this study to represent the social obligation of business vis-à-vis society is corporate social responsibility (CSR). The two main reasons this term was chosen are that it is widely encompassing, and managers and policymakers in the context of the study are familiar with the term as representative of the social obligation of the business.

Institutional theory is the conceptual lens used in this study, primarily because of its inherent contention that both contextual and institutional environments influence norms and practices of social responsibility (

Koleva and Quinn 2021;

Parsa et al. 2021).

Institutional theory has been criticized in the literature for predominantly focusing on the global diffusion and adoption of CSR practices and, in turn, neglecting how these practices are translated across national contexts (

Sieminski et al. 2020;

Filatotchev et al. 2021). To contend with this cross-national context translation issue and the identified importance of implicit CSR (

Carroll 2021), a dual construct of social responsibility is adapted to the study, namely, explicit, and implicit.

Explicit social initiatives include a business organization’s policies that are created deliberately to help increase societal welfare, while implicit social initiatives are a result of informal norms, values, and laws that may represent socially responsible business practices that are implied in a business context but are not well defined (

Dmytriyev et al. 2021). The significance of considering this dual construct in a developing-country context ensures that implicit initiatives that may not fit into the explicit form are accounted for in the research, and these informal norms, values, and policies have been identified in the literature as vital for CSR development (

Abreu et al. 2021;

Masahiro 2021).

1.1. Problem Statement

The main problem is that business organizations pursuing profits may create negative externalities that harm society. In the contemporary economy, these powerful and dominant institutions have substantial resources that can be utilized to alleviate social and environmental problems, consequently promoting their longevity and sustainability (

Yang et al. 2021).

Therefore, the study of social responsibility and sustainability in business is an important subject in the business society nexus because it provides insight into reaching the ideal condition of seamless integration of business in society, which is a business that has a predominantly positive impact on society. The subject of socially responsible business in developing countries is pertinent because these countries contain a large proportion of the world’s population and, subsequently, a large proportion of social, economic, and environmental issues.

1.2. Institutional Theory: A Conceptual Framework

The significance of institutional theory in this study lies in the assumption that institutional dynamics affect the behavior of organizations (

Khanal et al. 2021;

Notanubun 2021). Thus, considering the contextual effects of the underlying global and local institutions will help shed light on the institutional variables that drive the managers and policymakers of business organizations in developing countries to include explicit and implicit social initiatives in their organizational mandate.

In the literature, it is evident that the CSR engagement of SMEs in developing countries tends to focus on the internal agency as the main driver of social responsibility and neglects the mutual responsiveness and interdependency between agents and institutional structures (

Journeault et al. 2021). For this reason, the neo-institutional theory is considered because it recognizes that agency and organizational self-interests play a significant role in organizational adaptation to institutional environments (

Manogna 2021)

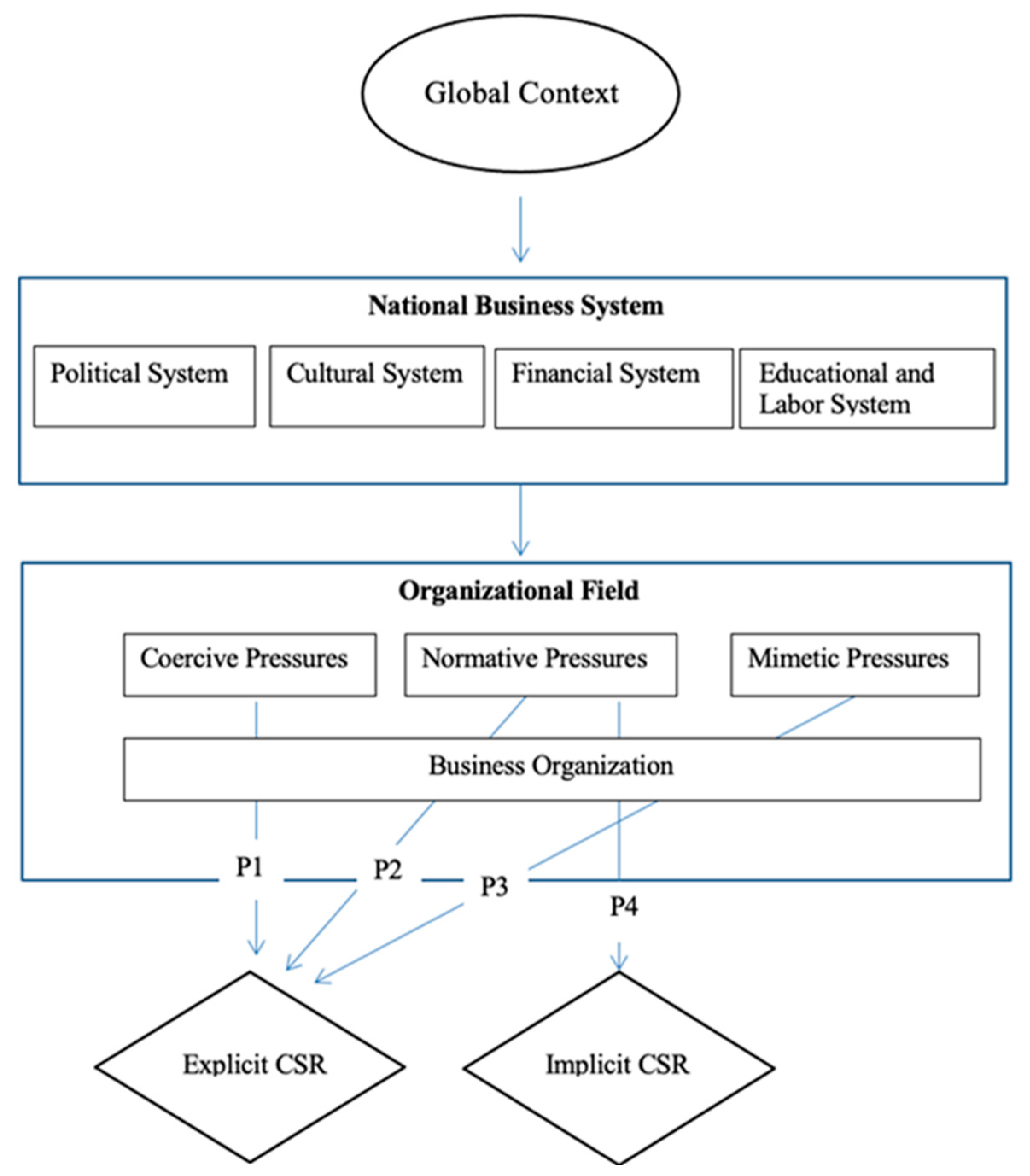

Contextual institutional pressures and internal agency are the basis for the conceptual model developed in this study. It is a multidimensional model that considers institutional pressures emanating from global institutional pressures, local pressures from institutions in the national business system (

Horiguchi 2021), isomorphic pressures from the organizational field (

Charpin et al. 2021), internal organizational responses to institutional pressures (

Oliver 1991), and how these pressures translate into explicit and implicit socially responsible initiatives. The main dimensions of the conceptual model are described briefly below.

First, global institutional pressures are the result of a multitude of global organizations that provide guidelines, metrics, and roadmaps to facilitate the proliferation of social responsibility on a global scale. Second, local institutional pressures from the national business system represent both formal institutions, such as government, associations, and civil groups, and informal groups, such as religious, cultural, and traditional norms in society (

Koleva and Quinn 2021). Third, isomorphic pressures in the organizational field, as identified by DiMaggio and Powell (

Charpin et al. 2021), are coercive, normative, and mimetic pressures. Fourth, internal organizational responses to institutional pressures related to organizational self-interest were best described by

Oliver (

1991).

These well-grounded conceptualizations within the subjects of the institutional theory were combined in this study to create a conceptual model with the goal of gaining insight into the institutionalization of implicit and explicit obligations in the business and society interface.

1.3. Context

As previously mentioned, the context chosen in this study is Lebanon, a country in the Middle East located on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea. The country is relatively small, covering an area of 10,452 square kilometers. Its population is approximately five million, with almost half of the population living in and around the capital city of Beirut.

Lebanon took independence on 22 November 1943, and formed a government structured as a parliamentary republic. The combination of the power divide between various religious groups and the fourteen years of civil war from 1975 to 1989 destabilized the country and stunted its development. Since the civil war ended with the creation of the “Taef” accord in 1989 Lebanon has been in a reconstruction stage with a primary focus on political, economic, and social structures. In this reconstruction stage, public debt rose to unprecedented levels. The GDP is approximately 45 billion USD, with a growth rate of approximately 0.9% (

World Bank 2014), and the public debt-to-GDP ratio is the third highest in the world at 142%. These conditions, coupled with regional instability, have in turn reduced the country’s ability to focus on growth and provide fiscal and monetary policies to improve key economic indicators, including stabilization of inflation, growth in GDP, and a reduction in the unemployment rate.

1.4. Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and CSR

Non-governmental agencies (NGOs) are participating in the international movement for business organizations to implement socially responsible business initiatives. There is a multitude of NGOs that are pushing for socially responsible business; some of these NGOs are active in developing countries and provide guidance to business organizations, and essentially the road map to social responsibility. Examples include the United Nations Global Compact (UNGC), the International Standards Organization with their introduction of (ISO 26000), the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) with their G4 guidelines, and PRIME organization to name a few.

The significance and influence of the aforementioned organizations are evident in the primary data. Although these NGOs are working in the right direction, some argue that they cannot make a large-scale impact on social problems because they do not have sufficient resources. If we can tap into the resources of large corporations, we will be able to make a large-scale impact (

Porter 2013). Policy changes in governments and implementation of hard law initiatives such as mandatory CSR reporting in the European Union are examples of countries taking the first step into ‘tapping into this large resource’ by changing laws and increasing coercive isomorphic pressures.

1.5. Objectives and Theoretical Contribution

The objective of this study is to make a theoretical contribution to the growing body of research pertaining to social responsibility in developing countries by delineating the underlying institutional factors and related isomorphic pressures, actor motivations, and organizational self-interests that influence organizations to adopt explicit and implicit social initiatives.

A qualitative research design involving a multiple case study was used in this study, with theoretically based propositions to guide the research. This study is grounded in institutional theory, specifically neo-institutional theory, primarily because of its inherent contention that both contextual and institutional environments influence CSR norms and practices.

2. Results

The high or low position of each variable was determined by the researchers based on the coding of the interviewee’s responses. The results of the strategic and operational interviews regarding predictive factors and responses are presented below. The results of the strategic interviews are illustrated in

Table 1, and the results of the operational interviews are illustrated in

Table 2.

The results displayed a high degree of consistency in and across cases. The results were analyzed based on the observed patterns within the context of propositions in the conceptual model. The five predetermined themes mentioned earlier are cause, constituents, content, control, and context. The predictive dimensions or observed patterns provided insight into the motivations of internal actors within the context of institutional pressures and responses of the business organizations chosen in the study and were used to verify, modify, or nullify the propositions in the conceptual model.

2.1. Results and Analysis, ‘Cause’ Predictive Factor

The first institutional antecedent or predictive factor is ‘cause’ and relates to why the organization is pressured to conform to institutional rules or expectations. The predictive dimensions are legitimacy and efficiency. Legitimacy relates to social fitness and efficiency is related to economic performance. The lower the degree of legitimacy and efficiency attained from conformity to institutional pressures, the greater the likelihood of organizational resistance to institutional pressures (

Oliver 1991).

In terms of the operational and strategic responses related to the cause-predictive factor, the themes identified by the responses of Bank 1 and Telecom 1 include both social legitimacy and financial efficiency in their responses; thus, we can conclude that these two dimensions of the cause-predictive factor are high, and the expected response according to Oliver and what is observed in the results is acquiescence or acceding to institutional pressures and implementing CSR.

The conclusions from the operational and strategic responses of Trading Company 1 and Bank 2 conflict with the other two responses. The legitimacy dimension of the predictive factor cause was high, and the financial efficiency dimension was low. This is not specified in the responses of Oliver, and this conflict may be due to the social legitimacy gained by adopting CSR efforts in Trading Company 1, and Bank 2 being viewed as more important than their objective of financial efficiency.

2.2. Results and Analysis, ‘Constituents’ Predictive Factor

The second predictive factor is ‘constituents’. This relates to who exerts institutional pressure. The predictive dimensions are the multiplicity of constituent demands and the dependence on institutional constituents. Multiplicity relates to the amount of multiple conflicting constituent expectations exerted on an organization. Dependence is related to the degree of external dependence on pressuring constituents. Institutional constituents are the collective normative order of the environment, which includes the government, professional organizations, pressure groups, interest groups, and the general public, which sometimes impose conflicting demands on the organization (

Oliver 1991).

The response observed when both the multiplicity and dependence were low in the analysis was acquired. This leads us to the conclusion that internal actor motivations are more powerful than international institutional pressures, instigating CSR use in the chosen cases.

2.3. Results and Analysis, ‘Content’ Predictive Factor

The third predictive factor is ‘content’. This relates to what norms or requirements organizations are being pressured to conform to. The predictive dimension is consistency of conformity with organizational goals. According to Oliver, when the ‘consistence’ predictive dimension is high and the ‘constraint’ predictive dimension is low the expected response is acquiesced. This theme was observed in this study, and we can conclude that the institutional pressures emanating from international sources affect CSR proliferation in developing countries, predominantly in organizations that have the objective of increasing social welfare.

2.4. Results and Analysis, ‘Control’ Predictive Factor

The fourth predictive factor is ‘control’. This relates to how institutional pressures are exerted, and the predictive dimensions are legal coercion or voluntary diffusion of norms.

According to Oliver, if coercive pressures are low and voluntary diffusion is low, then the anticipated response is ‘defy’, or not conceding to institutional pressures. The results of the study do not coincide with Oliver’s predictive responses because the cases chosen to have an acquiesce response in the face of low coercive pressure from regulative bodies. In view of this weak coercive institutional pressure, we can conclude that voluntary diffusion is the main driver of CSR activity implementation in the cases chosen.

2.5. Results and Analysis, ‘Context’ Predictive Factor

The fifth predictive factor is ‘context’. This relates to the characteristics of the environmental context in which institutional pressure is exerted. The predictive dimensions are environmental uncertainty and environmental interconnectedness. Environmental uncertainty relates to an organization’s inability to predict or anticipate future changes; interconnectedness refers to the density of inter-organizational relations among the occupants in the organizational field (

Oliver 1991).

In summary, the cause, constituents, and content predictive factors are related to normative pressures. The ‘control’ predictive factor relates to coercive institutional pressures. The ‘context’ predictive factor relates to mimetic institutional pressures. According to Oliver, the lower the level of uncertainty and interconnectedness in an organization’s environment, the lower the likelihood of conforming to institutional pressures. In the study, all the responses indicated high ‘uncertainty’, and high ‘interconnectedness’, and the results were as predicted by Oliver, which conforms to institutional pressures and implements CSR activities. What is evident in the analysis above is that institutional antecedents and predictive strategic responses are predominantly as indicated in

Oliver’s (

1991) conceptualization, and the strength of internal actor motivations, because even in the absence of coercive pressures, the cases chosen in the study conform to institutional pressures and engage in CSR activities.

3. Materials

The first part of the literature review categorizes and describes significant theories in the realm of CSR. This illustrates the multiple manifestations and multifaceted view of CSR in the literature. The second part discusses international organizations promoting social business obligations and their role in facilitating CSR proliferation. The purpose of this discussion is to illustrate the mechanics and objectives of growing international organizations influencing the perspectives of policymakers in business organizations in relation to their social obligations.

3.1. Categorization of Corporate Social Responsibility Theories

Over the years, many attempts have been made to map CSR theories with the primary objective of identifying and categorizing CSR approaches in business organizations. In one study, CSR theories were placed into three categories: ethical, altruistic, and strategic CSR (

Lantos 2001). Another study identified three categories of CSR initiatives: ethical responsibility, economic responsibility, and corporate citizenship (

Windsor 2006). The most significant empirical study identified four main categories of CSR theory: instrumental, political, integrative, and ethical (

Garriga 2021;

Garriga and Melé 2004). This is relevant to this study because it facilitates CSR identification in the analysis and discussion of the data in terms of the various manifestations CSR may take within a business organization and provides insight into the intent of business organizations to perform CSR in various forms.

Instrumental theories are tradition-bound. Their primary focus is on using CSR initiatives as a means of profit maximization and shareholder value maximization (

Fält and Steffensen 2021). Theories that fit into this category include advocates of using corporate social responsibility to gain a competitive advantage within a competitive context, and as a brand and reputation building tactic (

Wang et al. 2021).

Political theories highlight the notion of corporate power and its relationship with responsibility within society (

Carroll and Brown 2018). The focus of these theories is the idea that corporations have obligations towards society and markets where the feed and grow. The intent of political theory-based CSR is to ensure that a corporation is a good corporate citizen.

Integrative theories examine how business organizations integrate social demands into their business operations (

Garriga 2021;

Garriga and Melé 2004). The focus of these theories is to operate businesses in a way that has dual benefits for both business and society. Integrative theories on CSR integration intend to maximize the benefits for all stakeholders internally and externally by integrating the needs of society into business operations. The predominant integrative theories include creating shared value (CSV), corporate social innovation (CSI), stakeholder management, and corporate social performance.

Ethical theories are based on the idea that a corporation should do what is good for society. The focus of these theories is ethics. Ethical CSR theories aim to ensure that businesses operate within a set of ethical guidelines. Prevalent ethical theories include sustainability, supply chain sustainability, stakeholder theory, and the common good approach.

The empirical analysis of CSR theories by Garriga and Melé has important implications in this study because it identifies four primary manifestations of CSR. These categories provide insight into the possible cognitive basis of CSR initiatives undertaken by business organizations and help in the analysis by identifying the various manifestations that CSR may take within an organization.

3.2. Theoretical Framework and Conceptual Development

The focus of this study is to delineate the underlying institutional factors, related isomorphic pressures, and organizational self-interests that influence organizations to adopt and ultimately shape explicit and implicit forms of socially responsible practices practice. The institutional theory perspective is used in this study because its main premise is that to understand the dynamics of organizational change, we must examine the underlying institutional forces at play. In other words, to understand CSR dynamics, we must investigate institutional and social structures and how they affect the behavior of organizations (

Berberoglu 2018).

The literature shows that institutional theory embodies a broad domain with many forms and perspectives. Scholars in the field of the institutionalization of CSR view institutional theory as an effective perspective in the analysis pertaining to the proliferation of organizational practice in particular contexts for the analysis of international and local institutional pressures (

Alvesson and Spicer 2019;

Jain et al. 2017).

In developing countries, culture and societal norms are the primary forces in organizational change (

Alvesson and Spicer 2019). Institutional theories complement the subject because they emphasize the primacy of culture and highlight how social structures of resources and meanings are created to have significant effects. Thus, considering the effects of local and global institutions on policymakers in business organizations will help shed light on the isomorphic transformation in the formal structures of business organizations to include explicit and implicit CSR initiatives.

The theory related to CSR, such as the dual conceptualization of CSR, well-grounded conceptualizations of new institutional theory, isomorphic pressures, strategic responses to institutional processes, and the concept of the national business system (NBS), are combined in this study to create a conceptual model with four propositions that will be tested with the objective of gaining insight into the institutional pressures that are driving implicit and explicit CSR adoption by business organizations in a developing country context.

3.3. Theoretical Grounding and Conceptual Model Framework

This study adopts a multifaceted view in the institutional analysis of implicit and explicit CSR proliferation by considering institutional pressures from global, local, organizational, and internal actor motivations. Both external and internal factors are instrumental in gaining an understanding of the dynamics involved (

Alshbili and Elamer 2020).

The institutional pressures from the global context stem from the multitude of global institutions that promote socially responsible business practices by providing guidance to business organizations and essentially providing a road map to social responsibility. The influence of these types of organizations must be considered in the institutional analysis of CSR.

Institutional pressure from the local context includes both formal institutions, such as government, associations, and civil groups, and informal groups, such as religious, cultural, and traditional norms in society (

Arena et al. 2018). This institutional framework is best described as the national business system (NBS) which is shaped by historically grown institutional frameworks, which are composed of political, financial, educational, cultural, and labor systems (

Arena et al. 2018).

Institutional pressure from the organizational field is important in this study because the recognition of the multitude of actors involved is essential to gain an in-depth understanding of the dynamics relating to the underlying contextual pressures affecting an organization (

Charpin et al. 2021).

In the literature, it is evident that internal organizational responses and actor motivation in relation to institutional pressures vary depending on the nature and context of the pressures themselves (

Oliver 1991). In 1991, Oliver adapted resource dependency theory, and institutional theory created a typology of organizational responses to institutional pressures that range from passive conformity to active resistance. These responses are shown in

Table A1 It is her contention that organizations are not blind followers of institutionalization and may take many routes in response to institutional pressures, some more active than others, depending on contextual factors and the self-interests internal to the business organization. These institutional factors and the predicted strategic responses are shown in

Table A2.

The dual construct of CSR in this study is of prime importance primarily for two interrelated reasons. First, the variables and pressures affecting CSR practices can influence both implicit and explicit CSR activities. Second, including CSR duality in the study will ensure that implicit CSR is not ‘lost in translation’ across national contexts because implicit CSR in a developing country context may not fall into the explicit CSR framework and may be overlooked.

3.4. Conceptual Model Framework

The conceptual model tested in this study incorporates a multi-level institutional view by considering institutional pressures from the global context, institutional pressures from the local context, and institutional pressures from the organizational field to gain insight into the reasons business organizations engage in explicit and implicit CSR activities.

Institutional theory, specifically neo-institutional theory, is a useful perspective in capturing the complexity of CSR dynamics because of the integration of external institutional pressures from the global context, the organizational field, and self-interest of the organization itself (

Jamali and Karam 2018).

The first part of the model relates to global context, this includes institutional pressures emanating from the various international organizations promoting social responsibility in business on an international scale.

The second part of the model relates to local context best defined as the national business system (NBS). The NBS is the institutional framework of business, including both formal institutions such as government, associations, and civil groups; and informal groups such as religious, culture, and traditional norms in society. National business systems vary across countries which translates into variances in the source and strength of institutional pressures (

Okoye 2009).

The third part of the model relates to the isomorphic forces that are affecting business organizations in their respective organizational fields (

DiMaggio and Powell 1983). These various institutional pressures are affecting the perceptions of policy makers in business organizations in relation to their social obligation. This influence is driving the internal actors to engage in explicit or implicit social responsibility initiatives.

This conceptual model

Figure 1 below represents an institutional model of explicit and implicit CSR. It offers four propositions that will be tested to gain insight into the institutional impact of internal actor motivations in relation to explicit and implicit CSR initiatives. This model was created using deductive reasoning from theories and conceptualizations in the literature. Inductive reasoning will be used to test the propositions in the model through the analysis of the primary data. The objective is to accept, reject, or adjust the propositions based on real observations in the field to create a more robust model.

This conceptual model offers the following four propositions that were tested to gain insight into the institutional impact of internal actor motivations in relation to explicit and implicit CSR initiatives.

Proposition 1. Do coercive isomorphic pressures in the organizational field influence the engagement in explicit CSR practices of business organizations?

Proposition 1 provides insight into whether business organizations pursuing financial efficiency and legitimacy are prompted to make CSR activities as clear and well-defined as possible, which can be best achieved using explicit CSR initiatives.

Proposition 2. Do normative isomorphic pressures in the organizational field influence the engagement in explicit CSR practices of business organizations?

Proposition 2 provides insight into whether business organizations engage in explicit CSR because of organizational self-interest in meeting social obligations and demands in the pursuit of legitimacy. Although stakeholders are not as critical in Proposition 1, for an organization to reach the goal of legitimacy, their CSR activities must also be clear and well-defined, which can be best achieved using explicit CSR initiatives.

Proposition 3. Do normative isomorphic pressures in the organizational field influence the engagement in implicit CSR practices of business organizations?

Proposition 3 provides insight into whether business organizations engage in implicit CSR because of an internal drive of organizations to meet social obligations and demands in the pursuit of legitimacy. As social structures are considered informal, explicit CSR initiatives are not required.

Proposition 4. Do mimetic isomorphic pressures in the organizational field influence the engagement in explicit CSR practices of business organizations?

Proposition 4 provides insight into whether business organizations engage in explicit CSR practices because of mimetic isomorphic pressures. Business organizations in a situation of strategic uncertainty may model themselves to organizations perceived as successful in their field to gain legitimacy without considering the possibility of operational inefficiency.

These four propositions were tested in the analysis of the primary data gathered from the semi-structured interviews and were verified, modified, or nullified based on patterns that emerged in the data to provide insight into the reasoning of internal actor motivations and the explicit and implicit CSR manifestations in business organizations.

4. Methods

A multiple-case study was selected as the method of analysis for this qualitative study. The use of a multiple case study at a specific point in time with an inductive and deductive approach provides a deep understanding of CSR as experienced by individual business organizations (

Creswell 2013).

Primary data was gathered by conducting interviews with strategic top-level managers and their operational counterparts. This twin perspective of both top-level and operational-level management provided rich data that is necessary to understand institutional forces and their effect on business organizations in relation to explicit and implicit CSR initiatives in a developing country context.

The theoretical framework chosen in this study relates to theory-based propositions to guide research (

Yin 2009). These theoretically based propositions and the conceptual model were created using related theories and conceptualizations found in the literature. This is a deductive aspect of this study. Through data analysis, the previously mentioned propositions were accepted, rejected, or modified using inductive reasoning based on the actual primary data as observed in the field. The analysis in this study was be based on primary data because developing countries are plagued with an absence of reliable data, which has motivated many researchers to base their analysis on primary data.

The research methodology was completed using the six steps defined by

Jarzabkowski (

2008), as illustrated in

Table A3 These techniques, orientations, and approaches were chosen because there is a need for a complex and detailed understanding of the issue, which can only be established by directly meeting the people (

Creswell 2013) involved in CSR initiatives.

4.1. Sampling Methodology

Purposive or judgmental sampling was used to choose the business organizations that constituted the study population. The process of choosing cases began with the member list of indigenous Lebanese business organizations in the United Nations Global Compact (UNGC) Organization. Their voluntary membership in the UNGC is an indication that they are interested in developing social responsibility initiatives. The next step was to identify business organizations that illustrated a deep level of involvement in CSR. These were identified by experts in the field and their visible integration of CSR through business operations and structure.

The objective of this selection process is to choose cases that demonstrate acquiescence and compromise because these strategic responses imply that the business organization is engaging in and intends to develop and rationalize its CSR activities.

4.2. Population

The cases chosen were large indigenous corporations (over 1500 employees) in the following industries: banking, telecommunication, and trading. The data gathering was performed in Lebanon, which is a developing country as specified by the international statistical institute, and the World Bank.

Eight interviews were conducted in total with both the strategic leader of CSR, and the operational leader of CSR in each of the four cases chosen. The intent of interviewing the strategic leader was to gain insight why the business organization is engaging in explicit and implicit CSR from a strategic standpoint. The intent of interviewing the operational leader of CSR was to gain insight into why CSR activities are being implemented from an operational standpoint. In addition, two sets of responses from the same organization increased the reliability of the data by providing two sets of responses pertaining to the same subjects within the organization.

The classification of these cases as mentioned before, relates to Industry, size, and UNGC signatory position. The industry classification relates to the main industry the business organization is involved in. The size classification relates to the number of employees in the business organization. The UNGC signatory position classification represents the position of the business organization in the UNGC. The positions include members, and members of the steering committee. The regular member is a signatory that is active in CSR and has the intent to adopt CSR practices based on the ten principles of the United Nations global compact. The steering committee represents a member that has additional responsibilities that include being a part of governing the UNGC in Lebanon. The classification and details of the cases that will be studied are illustrated in

Table 3 below:

4.3. Data Collection Tool

The technique for collecting data involved capitalizing on two semi-structured interview schedules. One was designed for operational interviewees and the other for strategic interviewees within the same organization. Both interview schedules focused on the same subjects, but due to the allotted meeting duration with strategic interviewees, the number of questions was reduced. Interviewing both strategic and operational counterparts of the same business organization helped provide insights from a strategic and operational standpoint. In addition, using two sources of evidence enhances construct validity.

Semi-structured interviews were chosen because even though they have an overall structure and direction, they allow flexibility to include unstructured questioning, which may result in unexpected and insightful information coming to light, thus enhancing the findings (

Hair et al. 2003) and providing rich and holistic data relating to the subject at hand.

The interview questions were developed primarily based on the antecedents of strategic response conceptualization (

Table A2). According to Oliver, the choice of organizational responses to institutional pressures relates to contextual factors at play. These factors include cause, constituents, content, control, and context. These relate to why the organization is being pressured, who is exerting institutional pressures, to what norms the organization is being pressured to conform, the means institutional pressures are being exerted, and what are the characteristics of the business environment or context. The goal is to gain insight into why business organizations’ internal actors are performing implicit or explicit social responsibility initiatives in view of various institutional pressures and ultimately answer the research questions.

4.4. Interview Question Conceptualization

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with both strategic and operational leaders to gain insight into the cause, constituents, content, control, and context related to each type of isomorphic pressure. This provided insight into why business organizations’ internal actors are engaging in implicit and explicit CSR activities in relation to institutional pressures in the organizational field.

The strategic and operational interviews are based on the same underpinnings that relate to organizational responses to institutional pressures and include why these pressures are being exerted (cause), who is exerting them (constituents), how or by what means they are being exerted (content, control), and where they occur (context).

These questions also provide insight into whether internal actors engage in CSR initiatives because of normative institutional pressures in the organizational field. Normative isomorphic pressures result from an organization’s desire to better fit standards set by professional and educational institutions, certification, and accreditation bodies (

Charpin et al. 2021). Regulation is not always the responsibility of the government; there are cases in which industries often establish their own self-regulation by setting standards that members must follow (

Orhan et al. 2021).

5. Discussion

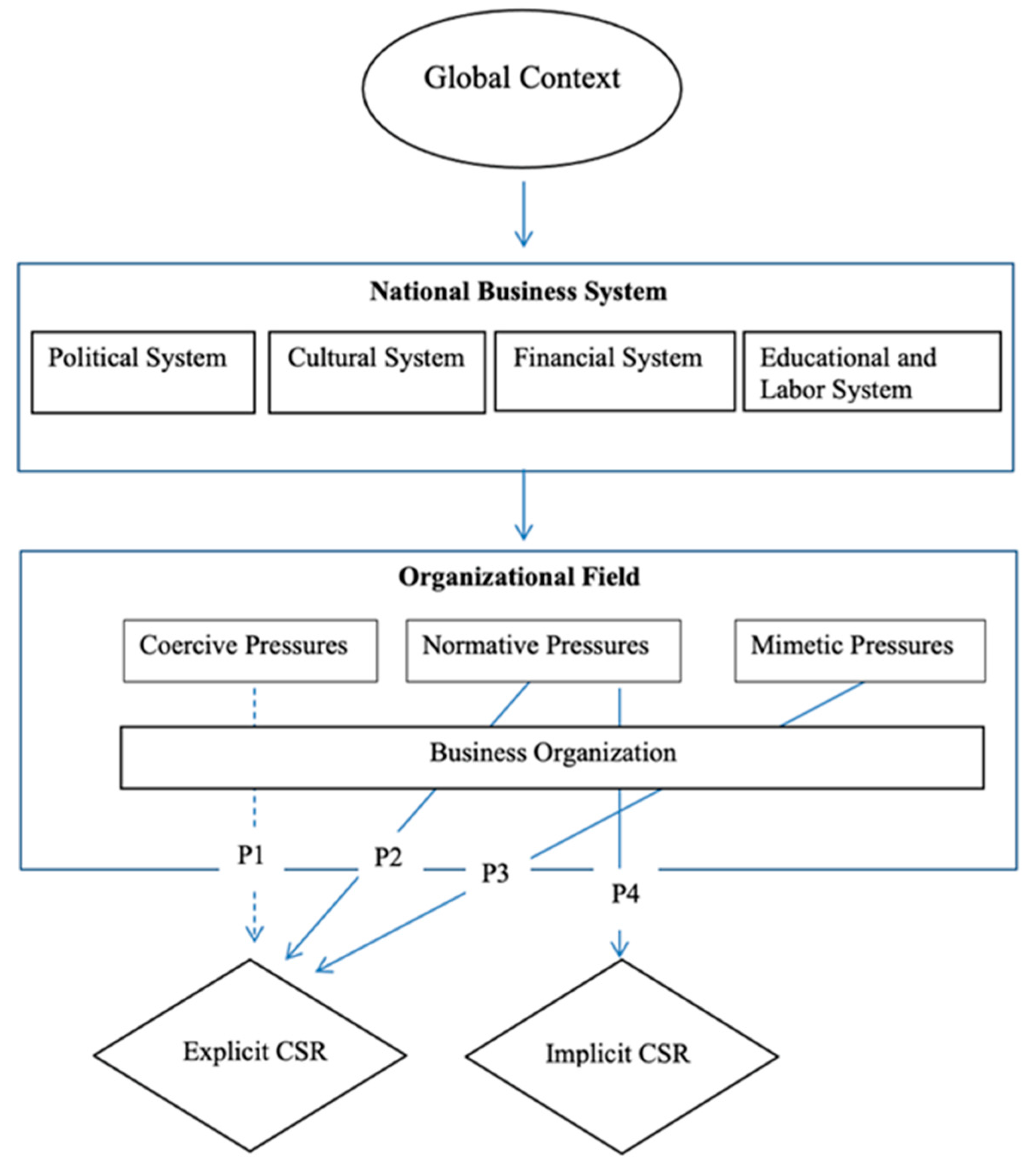

A deductive approach was used to create the initial conceptual model, and an inductive approach was used to verify, modify, or nullify the four propositions based on primary data. This created a more robust model because it related theoretical perception to actual events, as illustrated by the primary data and analysis (

Ven 2007).

Proposition 1. Do coercive isomorphic pressures in the organizational field influence the engagement in explicit CSR practices of business organizations?

The results of the study in relation to the ‘control’ predictive factor indicate coercive pressures are low, and voluntary diffusion is low, but the response is acquiescence. This does not coincide with Oliver’s predictive responses because the cases chose to engage in CSR efforts in a business environment that has weak or non-existent coercive pressure from regulative bodies. When coercive institutional pressures increase in strength, the expected outcome would be an increase in explicit CSR initiatives because business organizations should have clear and well-defined CSR policies and report these activities clearly to the formal organizations to avoid financial penalty, breaking the law, and losing legitimacy in their organizational field.

Proposition 1 cannot be nullified because explicit CSR is the expected and logical outcome of coercive institutional pressures. It cannot be accepted because it is evident in the analysis of the primary data that the strength of this institutional pressure is weak compared with normative and mimetic pressures. The conceptual model has been modified by representing the relationship between coercive institutional pressure and explicit CSR with a dotted line. This indicates the relative weakness of institutional pressure in influencing internal actor motivation in explicit CSR engagement.

Proposition 2. Do normative isomorphic pressures in the organizational field influence the engagement in explicit CSR practices of business organizations?

In the results and analysis of the primary data, there is a clear indication from all respondents that the institutions that promote CSR are consistent with the business organization’s goals of CSR implementation. The objective of the business organizations in this study is to conform to international institutions promoting CSR norms because they perceive that they will gain legitimacy in their organizational field, and conformity is consistent with their voluntary drive to increase social welfare. The requirement for conformity to these institutions is adherence to well-defined CSR guidelines and reporting, which can only be met using explicit CSR.

Proposition 2 cannot be nullified because of the clear evidence that normative institutional pressures influence internal actors to engage in explicit CSR. Modification is also not necessary, because there is evidence that normative institutional pressures influence internal actors to engage in explicit CSR. Therefore, Proposition 2 is accepted, and remains unchanged in the conceptual model.

Proposition 3. Do normative isomorphic pressures in the organizational field influence the engagement in implicit CSR practices of business organizations?

The past CSR activities performed by the business organizations in the study were not clearly defined and well-articulated, and can be considered implicit CSR. These efforts, which were initially implicit CSR efforts, are now being transformed into explicit CSR efforts by business organizations to better fit the international definition of CSR with the objective of legitimacy on a global level. This is consistent with recent literature about CSR in a developing country context, which suggests that firms in developing countries engage in modest forms of explicit CSR as a response to global pressures but have inherent forms of implicit CSR shaped by culture, religion, and societal norms (

Jamali and Karam 2018).

Proposition 3 cannot be nullified because of the clear evidence that normative institutional pressures influence internal actors to engage in implicit CSR outcomes. Modification is also unnecessary because of the clear relationship between normative pressure and implicit CSR in the primary data. Proposition 3 is accepted and remains unchanged in the conceptual model.

Proposition 4. Do mimetic isomorphic pressures in the organizational field influence the engagement in explicit CSR practices of business organizations?

Evidence of mimetic institutional pressures can be identified in the results of the predictive factor ‘context’ as defined by Oliver in 1991. The predictive dimensions were uncertainty and interconnectedness. As previously mentioned, uncertainty relates to an organization’s inability to predict future changes, and interconnectedness refers to the density of inter-organizational relations among the occupants in the field (

Oliver 1991).

The results and analysis of the primary data relating to mimetic pressures and explicit CSR are consistent with those in the literature. In the literature, this rise in explicit CSR in developing countries is attributed to mimetic isomorphic pressures emanating from the global context, cultural variables, and education system (

Matten and Moon 2020). The proliferation of explicit CSR due to mimetic institutional pressures in a developing country context is evident in the literature and research performed in many geographical locations, such as Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

Proposition 4 cannot be nullified because of clear evidence that mimetic institutional pressures influence internal actors to engage in explicit CSR initiatives. Modification is also not necessary because of the clear relationship between mimetic pressure and explicit CSR in the primary data. Proposition 4 is accepted and remains unchanged in the conceptual model.

Conceptual Model Revisited

Using the deductive approach to create the initial conceptual model and using the inductive approach to verify, modify, or nullify the four propositions created a more robust model because it relates theoretical perceptions, or what is in the literature, to actual events, as illustrated by the primary data and analysis (

Ven 2007). The new conceptual model is a revised institutional model of explicit and implicit CSR and is shown below in

Figure 2. The main difference is the indication of coercive institutional pressure as being very weak in the motivation of internal actors within business organizations to engage in explicit CSR initiatives.

6. Conclusions

Based on the analysis of the primary data and the modified conceptual model, there is clear evidence of predominantly normative and mimetic institutional pressures affecting internal actors’ engagement in explicit CSR initiatives. Coercive institutional pressures have been identified as weak or nonexistent, and these results are consistent with those found in the literature. Normative and mimetic institutional pressures stem from the global business context through international organizations such as the UN Global Compact, the Global Reporting Initiative, and the International Standards Organization. They also stem from the organizational field in the form of mimetic pressures that instigate business organizations to mimic successful organizations locally and internationally with explicit CSR initiatives.

Based on the research in this study, we can also conclude that normative institutional pressure is a significant factor in isomorphic organizational changes for business organizations in developing countries chosen to engage in implicit CSR. Coercive and mimetic institutional pressures were identified as weak. The normative institutional pressures affecting implicit CSR stem from elements in the national business system, specifically the ideologies of cultural and religious institutions and their effect on internal actors to engage in ethical behavior. These CSR efforts are considered implicit because they are instigated by informal institutions in the national business system and do not require strict adherence to CSR in terms of clarity and reporting. These pressures drove implicit CSR, even before the explicit CSR movement began.

6.1. Contributions of Study

This study contributes to the institutionalization of socially responsible business practices in developing countries by providing insights into the salient institutional pressures affecting business organizations in their adoption of implicit and explicit CSR activities.

6.2. Theoretical Contribution

The main theoretical contribution of this study is the conceptual model that provides an institutional framework that can be used by future researchers to study the institutionalization of CSR. This model is novel in that it identifies the importance of the duality of CSR and the importance of international institutions in facilitating explicit CSR proliferation.

Another theoretical contribution is the consideration of CSR duality as an essential conceptualization in the institutional study of CSR. This dual construct of CSR is of prime importance for two interrelated reasons. First, the variables and pressures affecting CSR practices can influence either the use of implicit or explicit CSR activities. Second, including both implicit and explicit CSR in the study will ensure that implicit CSR is not ‘lost in translation’ across national contexts. As mentioned, implicit CSR in a developing country context may not fall into the explicit CSR framework and may be overlooked.

6.3. Practical Contribution

This study identifies the importance of international institutions such as the UN Global Compact, Global Reporting Initiative, and International Standards Organization in relation to explicit CSR advancement in developing countries. These international institutions are aiding and guiding a handful of business organizations that perceive CSR as an integral part of economic and social development. They facilitate explicit CSR engagement for companies that perform implicit CSR in an ad hoc manner and companies that are new to CSR.

The adoption of conceptualizations and findings from this growing body of research will provide local organizations, both public and private, within developing countries, and international organizations’ strategic insight in aiding the proliferation of CSR. As more scholars engage in research on this subject, new implications and strategies can be developed. These new implications and strategies will potentially have a positive effect on the societal welfare of developing countries, which is significant because these countries need it the most.

6.4. Managerial Implications

Managers of business organizations worldwide are in a constant flux in the mechanics and structure of their business models and strategies to create a symbiotic existence that is well adapted to their ever-changing environment. The dynamics of the international business environment, coupled with the significant empirical evidence that corporate social responsibility can positively affect social progress and potentially both stakeholder and shareholder wealth (

Cheema et al. 2020), has materialized into an increased international concern for socially responsible business practices. Managers should be aware of this concern and adapt their business models accordingly.

In view of this increased concern for social responsibility, if social responsibility is absent in a business organization, managers should take the initiative to begin considering this subject. In the case that a business organization engages in implicit social responsibility, managers must ensure that these activities are clearly defined and reported using guidelines and methods provided by international business organizations promoting explicit social responsibility to gain legitimacy in their organizational field.

It is evident that implicit forms of CSR exist because they are embedded in the national business systems of many countries and must be accounted for. What is changing and continuing to change are the institutional forces that promote explicit CSR from multiple institutions and their impact on business organizations. Managers should be mindful of these isomorphic pressures and consider them in their strategic plans to ensure the proper fit of their business organizations. Managers should develop their implicit CSR into explicit CSR so that their social responsibility initiatives are more defined, reported, and identified in the international business community. This will allow them to gain legitimacy on an international scale and will be an integral part of their operations in international markets. This is especially important in a globalized contemporary business environment.

6.5. Limitations and Future Studies

The limitations include the conceptual lens used, elements of the research design, type of sampling used, interviewees chosen, and transferability of findings.

The first limitation is related to the conceptual lens used in this study. An institutional perspective was used to create a conceptual model and analyze the primary data. Many other perspectives could have been used, such as agency theory, resource dependency theory, theory of institutional logic, slack theory, or relational governance theory.

The second limitation is related to the type of sampling used. Purposeful sampling was used in the study, and cases were identified through a list of signatories of the UN Global Compact network in the context chosen. Another study could be conducted on the same subject using business organizations that are not found in the UN Global Compact Network, which would complement this research and may potentially result in an alternative point of view, adding to the understanding of the subject at hand.

The third limitation relates to the interviewees chosen from the business organization. They were all operational and strategic CSR leaders in their respective businesses. The same study can be conducted using interviewees from the same organizations that were not involved in CSR initiatives. This can be compared with the results of this study to analyze the variance in perception within the same organization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K.; methodology, S.K.; software, S.K. and R.K.; validation, S.K., R.K. and R.A.; formal analysis, S.K., R.K. and R.A.; investigation, S.K.; resources, S.K., R.K. and R.A.; data curation, S.K., R.K. and R.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K.; writing—review and editing, S.K., R.K. and R.A.; visualization, S.K., R.K. and R.A.; supervision, S.K., R.K. and R.A.; project administration, S.K., R.K. and R.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available with authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Strategic responses to institutional processes (adapted from

Oliver (

1991, p. 152)).

Table A1.

Strategic responses to institutional processes (adapted from

Oliver (

1991, p. 152)).

| Strategies | Tactics | Examples |

|---|

| Acquiesce | Habit | Following invisible taken for granted norms |

| | Imitate | Mimicking institutional models |

| | Comply | Obeying rules and accepting norms |

| Compromise | Balance | Balancing the expectation of multiple constituents |

| | Pacify | Placating and accommodating institutional elements |

| | Bargain | Negotiating with institutional stakeholders |

| Avoid | Conceal | Disguising nonconformity |

| | Buffer | Loosening Institutional attachments |

| | Escape | Changing goals, activities, or domains |

| Defy | Dismiss | Ignoring explicit norms and values |

| | Challenge | Contesting rules and requirements |

| | Attack | Assaulting the sources of institutional pressures |

| Manipulate | Co-opt | Importing Influential constituents |

| | Influence | Shaping values and criteria |

| | Control | Dominating institutional constituents and processes |

| Predictive | Strategic Responses |

|---|

| Factor | Acquiesce | Compromise | Avoid | Defy | Manipulate |

|---|

| Cause | | | | | |

| Legitimacy | High | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Efficiency | High | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Constituents | | | | | |

| Multiplicity | Low | High | High | High | High |

| Dependence | High | High | Moderate | Low | Low |

| Content | | | | | |

| Consistence | High | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low |

| Constraint | Low | Moderate | High | High | High |

| Control | | | | | |

| Coercion | High | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low |

| Diffusion | High | High | Moderate | Low | Low |

| Context | | | | | |

| Uncertainty | High | High | High | Low | Low |

| Interconnectedness | High | High | Moderate | Low | Low |

Table A3.

Six stages in the analysis of the primary data (adapted from

Jarzabkowski 2008).

Table A3.

Six stages in the analysis of the primary data (adapted from

Jarzabkowski 2008).

| Stage | Description | Process | Output |

|---|

| 1 | Identify the characteristics of the sample | Classify the cases based on size, industry, and UNGC signatory position | This will provide a classification of each case in the sample. |

| 2 | Perform semi structured interviews with strategic and operational leaders of business organizations active in CSR | Creating a semi structured interview schedule, and engaging in face to face interviews with strategic and operational leaders of CSR. | This will provide e with the primary data that will consists of eight interviewed. |

| 3 | Code data based on predetermined themes which are cause, constituents, content, control, and context. | The use of hand coding and Nvivo software to perform coding of the data. | An empirical analysis will be performed to help identify patterns within the context of the primary data. |

| 4 | Related coded data to predetermined themes which are cause, constituents, content, control, and context. | Related coded data to predetermined themes to gain insight into the four propositions of the conceptual model. | This will provide coded information based on the predetermined themes that will be used in the analysis. |

| 5 | Analyze the data within the context of the propositions in the conceptual model. | Analyze the coded data based on predetermined themes in the context of the propositions in the conceptual model. | The identification of issues or gaps in the conceptual model. |

| 6 | Accept, reject, or modify the propositions. | Use the output of the previous step to accept, reject, or modify propositions. | This will provide insight into why internal actions of business organizations are engaging in explicit and implicit CSR practice. |

References

- Abreu, Monica Cavalcanti Sa de, Rômulo Alves Soares, Robson Silva Rocha, and João Maurício Gama Boaventura. 2021. Salience of multiple actors involved in formal and informal governance systems encouraging corporate social responsibility in an emerging market. Competition & Change 26: 603–28. [Google Scholar]

- Alshbili, Ibrahem, and Ahmed A. Elamer. 2020. The influence of institutional context on corporate social responsibility disclosure: A case of a developing country. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment 10: 269–293. [Google Scholar]

- Alvesson, Mats, and André Spicer. 2019. Neo-institutional theory and organization studies: A mid-life crisis? Organization Studies 40: 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, Marika, Giovanni Azzone, and Francesca Mapelli. 2018. What drives the evolution of Corporate Social Responsibility strategies? An institutional logics perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production 171: 345–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berberoglu, Aysen. 2018. Impact of organizational climate on organizational commitment and perceived organizational performance: Empirical evidence from public hospitals. BMC Health Services Research 18: 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, Archie. 2021. Corporate social responsibility: Perspectives on the CSR construct’s development and future. Business & Society 60: 1258–78. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, Archie B., and Jill A. Brown. 2018. Corporate social responsibility: A review of current concepts, research, and issues. Corporate Social Responsibility 2: 39–69. [Google Scholar]

- Charpin, Remi, E. Erin Powell, and Aleda V. Roth. 2021. The influence of perceived host country political risk on foreign subunits’ supplier development strategies. Journal of Operations Management 67: 329–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, Sadia, Bilal Afsar, and Farheen Javed. 2020. Employees’ corporate social responsibility perceptions and organizational citizenship behaviors for the environment: The mediating roles of organizational identification and environmental orientation fit. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 27: 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, John. 2013. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design, Choosing among Five Approaches, Los Angeles, 3rd ed. Newcastle upon Tyne: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, Paul J., and Walter W. Powell. 1983. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review 1983: 147–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmytriyev, Sergiy D., R. Edward Freeman, and Jacob Hörisch. 2021. The relationship between stakeholder theory and corporate social responsibility: Differences, similarities, and implications for social issues in management. Journal of Management Studies 58: 1441–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fält, Jenny, and Cassandra Steffensen. 2021. CSR Engagement in Profit Maximizing Organizations: An Overview of the Main Driving Forces, Financial Incentives, and Considerations in Business Decisions for Swedish Commercial Real Estate Companies. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1575890&dswid=9980 (accessed on 16 October 2022).

- Filatotchev, Igor, R. Duane Ireland, and Günter K. Stahl. 2021. Contextualizing management research: An open systems perspective. Journal of Management Studies 59: 1036–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garriga, Elisabet. 2021. 3 Evolution of the Business and Society Field to a From a Functionalist Orientation. The Routledge Companion to Corporate Social Responsibility 2021: 31. [Google Scholar]

- Garriga, Elisabet, and Domènec Melé. 2004. Corporate social responsibility theories: Mapping the territory. Journal of Business Ethics 53: 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joe F., Michael Page, and Niek Brunsveld. 2003. Essentials of Business Research Methods. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Horiguchi, Shinji. 2021. Making implicit CSR explicit? Considering the continuity of Japanese “micro moral unity”. Business Ethics, the Environment & Responsibility 30: 311–22. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, Tanusree, Ruth V. Aguilera, and Dima Jamali. 2017. Corporate stakeholder orientation in an emerging country context: A longitudinal cross industry analysis. Journal of Business Ethics 143: 701–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, Dima, and Chalotte Karam. 2018. Corporate social responsibility in developing countries as an emerging field of study. International Journal of Management Reviews 20: 32–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarzabkowski, Paula. 2008. Shaping strategy as a structuration process. Academy of Management Journal 51: 621–50. [Google Scholar]

- Journeault, Marc, Alexandre Perron, and Laurie Vallières. 2021. The collaborative roles of stakeholders in supporting the adoption of sustainability in SMEs. Journal of Environmental Management 287: 112349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanal, Puspa, Fabio Bento, and Marco Tagliabue. 2021. A scoping review of organizational responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in schools: A complex systems perspective. Education Sciences 11: 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koleva, Petya, and Lee Quinn. 2021. CSR Uptake in Non-Western Contexts: The Impact of Institutional Environment and Entrepreneurs. In Academy of Management Proceedings. Briarcliff Manor: Academy of Management, vol. 2021, p. 12873. [Google Scholar]

- Lantos, Geoffrey P. 2001. The boundaries of strategic corporate social responsibility. Journal of Consumer Marketing 18: 595–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manogna, Ron L. 2021. Ownership structure and corporate social responsibility in India: Empirical investigation of an emerging market. Review of International Business and Strategy 31: 540–55. [Google Scholar]

- Masahiro, Hosoda. 2021. Adoption of integrated reporting and changes to internal mechanisms in Japanese companies. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 29: 421–34. [Google Scholar]

- Matten, David, and James Moon. 2020. Reflections on the 2018 decade award: The meaning and dynamics of corporate social responsibility. Academy of management Review 45: 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notanubun, Zainuddin. 2021. The effect of organizational citizenship behavior and leadership effectiveness on public sectors organizational performance: Study in the Department of Education, Youth and Sports in Maluku Province, Indonesia. Public Organization Review 21: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoye, Adaeze. 2009. Theorising corporate social responsibility as an essentially contested concept: Is a definition necessary? Journal of Business Ethics 89: 613–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, Christine. 1991. Strategic responses to institutional processes. Academy of Management Review 16: 145–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan, Mehmet A., Sylvaine Castellano, Insaf Khelladi, Luca Marinelli, and Filippo Monge. 2021. Technology distraction at work. Impacts on self-regulation and work engagement. Journal of Business Research 126: 341–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsa, Sepideh, Narisa Dai, Ataur Belal, Teng Li, and Guliang Tang. 2021. Corporate social responsibility reporting in China: Political, social and corporate influences. Accounting and Business Research 51: 36–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, Michael. 2013. Why Business Can Be Good at Solving Social Problems, Filmed June 2013, Posted on October 2013, Ted Global 2013, ted.com. Available online: https://youtu.be/0iIh5YYDR2o (accessed on 16 October 2022).

- Sieminski, Marek, Ewa Wedrowska, and Krzysztof Krukowski. 2020. Cultural aspect of social responsibility implementation in SMEs. European Research Studies Journal 23: 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ven, Andrew. 2007. Engaged Scholarship: A Guide for Organizational and Social Research. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Han-Min, Tiffany Hui-Kuang Yu, and Chih-Yi Hsiao. 2021. The causal effect of corporate social responsibility and corporate reputation on brand equity: A fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis. Journal of Promotion Management 27: 630–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windsor, Duane. 2006. Corporate social responsibility–three key approaches. Journal of Management Studies 43: 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. 2014. Website Lebanon. Available online: www.data.worldbank.org/country/Lebanon (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- Yang, Xiaodong, Jinning Zhang, Siyu Ren, and Qiying Ran. 2021. Can the new energy demonstration city policy reduce environmental pollution? Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. Journal of Cleaner Production 287: 125015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Robert K. 2009. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed. Newcastle upon Tyne: Sage. [Google Scholar]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).