Abstract

Participation in the political process is the fundamental right and responsibility of a citizen. Online political participation has gained popularity as it is convenient and effective. Political crowdfunding helps political candidates and parties pledge funds, usually small, from a large population and seek support through marketing campaigns during elections. In November 2020, when there were presidential elections in the US and the world was facing a global pandemic from COVID-19, political crowdfunding was a helpful method to communicate the political agenda and seek funding. The study aims to examine the intentions of US citizens to participate in political crowdfunding amid the COVID-19 pandemic. The study will integrate two models—the theory of planned behavior and civic voluntarism model—to check intentions and, in addition, the influence of COVID-19. The data were collected from 529 respondents from the US before the elections. The data were analyzed through a partial least squared structural equation modeling technique with SmartPLS 3.2. The results suggested that political efficacy and online community engagement have a positive influence on the intention to participate in political crowdfunding. Further, all three factors of TPB have a significant positive influence on intention. The perceived threat variable of COVID-19 does impact the attitude towards political crowdfunding. The study will be helpful for crowdfunding platforms and political contenders to examine the factors that can help them to seek maximum funds from the public and, at the same time, examine the effectiveness of their political communications.

1. Introduction

The main concept of crowdfunding is driven by micro-finance and crowdsourcing, with more specific usage for fundraising (Mollick 2014). Crowdfunding projects are most well known in the entrepreneurship sector because it allows entrepreneurs to raise funds from the public. Crowdfunding for political purposes gained people’s attention when Barack Obama managed to secure more than USD 700 million in 2008 through what they called grassroots fundraising. However, this campaign was not the first to exploit the power of technology and communication for promotion (Cogburn and Espinoza-Vasquez 2011). However, people can relate to the Obama campaign as the most successful political crowdfunding campaign. Based on this, we use the term political crowdfunding to define the use of crowdfunding for political purposes. Research shows that the reliance on small donors may help democratize the electoral process by expanding the scope of political participation for citizens and level the playing field for incumbents, challengers, and open-seat candidates (e.g., Culberson et al. 2018), especially for female candidates (Heberlig and Larson 2020). Political crowdfunding has become a widely accepted political norm, not only in the US but also in other countries. For example, John Tsang raised more than USD 500,000 within 48 h for contesting Hong Kong’s leadership elections through the Kickstarter project (The Straits Times 2017).

As political crowdfunding is a new social phenomenon in the social media age, few studies have been conducted to investigate the key factors predicting people’s intent to participate in political crowdfunding (e.g., Kusumarani and Zo 2019; Baber 2020). The 2020 US presidential election happened when the US and the rest of the world were facing the global COVID-19 pandemic. We found one study that links political support and risk perception of COVID-19, by Barrios and Hochberg (2020). They found that those who are in favor of Trump showed lower perceptions of risk during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, as people’s political attitudes and participation are suggested to be affected by the pandemic, these links have not gained much attention from researchers. This study seeks to be the first to understand the intention of citizens to donate small amounts to support presidential candidate campaigns amid the COVID-19 pandemic by using the 2020 US presidential election as the main focus. We believe that the present study can bring new insight into how the COVID-19 pandemic is affecting political attitudes and behavior, which can be helpful for countries that are scheduled to go for elections in the future.

To understand what factors drive citizens’ intention to participate in political crowdfunding, we chose a robust model, named the civic voluntarism model (CVM). The CVM posits that people participate in politics because of the availability of resources, psychological engagement, and opportunities (Verba et al. 1995). This theory has been applied to different contexts, such as youth and college students’ participation in politics (Kim and Khang 2014; Kirbiš et al. 2017), among older adults (Nygård and Jakobsson 2013) and crisis periods (Guo et al. 2021). Furthermore, we found studies that used CVM to explain civic participation in different countries (e.g., Nygård and Jakobsson 2013; Sheppard 2015). Cogburn and Espinoza-Vasquez (2011) stated that the Obama 2008 campaign, which was facilitated by social media and Web 2.0 tools, promoted active civic engagement and helped to raise money.

To our knowledge, no research applies CVM to identify the determinants of political crowdfunding in US presidential elections and a pandemic context. Our research seeks to address the gap. This study also draws upon the theory of planned behavior (TPB) as the most common model, which comprises three factors—attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control—to test people’s intentions in performing a particular behavior. We further found studies that applied the TPB in the context of crowdfunding and established the relevance of this robust model to test the intentions of contributors to participate in crowdfunding campaigns, as well as the intentions of project owners to raise the funds through this novel method (e.g., Shneor and Munim 2019; Chen et al. 2019; Baber 2020). The present study is probably the first survey research project to integrate the CVM and TPB to predict U.S. citizens’ intentions to participate in political crowdfunding, in a very competitive US presidential election and during the global COVID-19 pandemic. The TPB will help to understand the intentions towards crowdfunding and CVM will aid in predicting the socio-economic factors accentuating civic engagement. Furthermore, we added social distancing efficacy as one of the influencing factors that affect people’s attitudes toward political crowdfunding during the pandemic. The integration of these two models will help to develop a framework that will cover both the information system theory and political participation theory. Our empirical study will test, via PLS-SEM, the robustness of our integrated model and identify what key determinants predict online citizens’ intent to engage in political crowdfunding in the US Election 2020 and COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Building

Crowdfunding (CF), which was only regarded as an alternative method of financing, now triggers increased awareness in society, while it is also an effective marketing tool for campaign owners (Konhäusner et al. 2021a; Fanea-Ivanovici and Baber 2021). Political marketing through digital networks has created a better level of democratic participation, civic engagement, and social activism (Khairiza and Kusumasari 2020). As the costs of paper and printing increased and the reluctance of advertisers to place ads in print publications, people shifted to independent print media using CF platforms to finance their projects (Le Masurier 2012). This implies the dynamic role of CF in helping the media for raising funds and also becoming a source of new information (Baber and Fanea-Ivanovici 2021). Sayedi and Baghaie (2017) even suggested that CF is now being increasingly used as a marketing tool, rather than a source of funding. Only limited research has been conducted on marketing practices, specifically crowdfunding, and their effect on the efficiency of the campaign (Konhäusner et al. 2021b). The present study will explain the effectiveness of crowdfunding as a communication channel for politicians and parties to communicate their political agenda and, at the same time, seek financial donations from the public. We assume that a higher intention to participate in crowdfunding campaigns implies that people believe that CF campaigns are effective means to receive communication from political players. It will be interesting to check the intentions of people to participate in CF through CVM and TPB models in the presence of the COVID-19-pandemic factor for the first time.

2.1. Resources

People need resources to participate in civic activities (Brady et al. 1995; Verba et al. 1995) in the form of finance, time, and technology. Levin-Waldman (2013) measured financial resources by the level of income that individuals have and found that it is related to their intention to engage in civic participation. An opposite finding of the strength of income on political participation through crowdfunding was reported by Oni, Oni et al. (2017), and Kusumarani and Zo (2019). According to the findings, resources are significant but not the most influential factor in people’s decision to contribute to a political crowdfunding campaign. This is understandable because of the nature of crowdfunding, which requires less money to participate.

Even though as little as USD 1 is needed to participate in a crowdfunding campaign, the COVID-19 pandemic affected people’s financial resources (Li and Mutchler 2020; Clark et al. 2021). We argue that in the political crowdfunding context during COVID-19, financial resources will remain a significant factor, following Igra et al. (2021). Based on this logic, we argue that the form of financial resources will positively influence people’s intention to participate in political crowdfunding during a pandemic. This will force people to set their priorities to fit the situation.

Time acts as a resource that is used by citizens to exercise civic participation. To participate in politics, citizens need to spare their time, such as voting, listening to debate, and consuming news. To measure time as resources, we can ask individuals the time allocated for political activity by hours spent (Brady et al. 1995). During the lockdown and social distancing measurement, studies reported an increase in the amount of free time that people have (Colizzi et al. 2020; Liu et al. 2020), allowing people to have more time to attend online education (Liu et al. 2020). As time as a resource is required to participate in politics, we see that the pandemic will actually push people to participate in politics in the form of crowdfunding. The 2020 US presidential elections that were conducted during COVID-19 are unique because citizens were required to avoid public places and rallies.

In the political crowdfunding setting, technology as a skill is needed to log on to the Internet and participate in a crowdfunding campaign. This is in line with previous research, which found that Internet usage directly affects political participation (Tolbert and McNeal 2003; Bakker and De Vreese 2011; Lee 2016; Campante et al. 2017). The availability of internet technology allows citizens to be politically knowledgeable, increase communication capability, and create a virtual public sphere, in which citizens can gather (Polat 2005; Campante et al. 2017). Therefore, the skillful use of Internet technologies should facilitate people’s political behavioral intentions to participate in politics, including political crowdfunding. On this basis, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 1a (H1a).

Resources in the form of finance will influence US citizens’ intention to participate in political crowdfunding.

Hypothesis 1b (H1b).

Resources in the form of time will influence US citizens’ intention to participate in political crowdfunding.

Hypothesis 1c (H1c).

Resources in the form of technology will influence US citizens’ intention to participate in political crowdfunding.

2.2. Political Interest

People’s level of interest in politics can be briefly understood as Political Interest. This level of interest affects voting behavior, political contributions, and other political activities (Carter 2006; Ritter 2008; Kirbiš et al. 2017). Research on the effect of political interest in the crowdfunding context was conducted by Kusumarani and Zo (2019). They found that the level of political interest affects people’s intention to participate in political crowdfunding. This result was then confirmed by Baber (2020), who used Indian adults as respondents.

A good crowdfunding campaign is characterized by the detailed information that a campaigner puts on the campaign’s main page (Koch and Siering 2019). A standard crowdfunding campaign page consists of a description section, in which the campaigner can put details related to the campaign. People with political interest will be expected to find more information regarding political crowdfunding campaigns from the information being given on the crowdfunding platform and from different information sources. Based on this logic, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2a (H2a).

Political interest will influence US citizens’ intention to participate in political crowdfunding.

2.3. Political Efficacy

Political efficacy is a concept that represents a measure of efficacy related to actions within the current political system (Tausch et al. 2011). Clarke and Acock (1989) use the definition of political efficacy as “how individuals feel that their political action does have, or can have, an impact upon the political process”. There are two types of political efficacy that researchers explore: internal and external efficacy. Internal efficacy is how politically skillful a citizen is to influence the political system, while external efficacy is how citizens see governments responding to political issues (Clarke and Acock 1989).

The availability of Internet technology is suggested to be related to a citizen’s political efficacy (Kenski and Stroud 2006). The reason for this is that the Internet allows citizens to find information about political events and issues. The perceived political efficacy of individuals can affect the way people are more critical of certain politicians because they think that they could do a better job (Rico et al. 2020). Political efficacy has been consistently shown to be a significant, positive predictor of online/offline political participation (Yang and DeHart 2016) and voting intent/behavior (Um 2018). Thus, we are proposing the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2b (H2b).

Political efficacy will influence US citizens’ intention to participate in political crowdfunding.

2.4. Political Awareness

Political awareness or knowledge is the degree to which people are deliberately exposing themselves to political issues, become knowledgeable of and/or understand the political institutions, processes, issues, events, and actors (Ran et al. 2016). In this study, we gauged both the objective and subjective political knowledge of our participants by asking two factual questions and three questions of self-assessment, as exemplified by previous studies (e.g., Leonhard et al. 2020). Political marketing is more effective to the target audience who are politically aware and knowledgeable. In fact, highly knowledgeable individuals utilize the information better, share with other people, and aid in their decision making (Falkowski and Jabłońska 2019).

Most scholars agree that people’s political knowledge is derived from online and offline news media uses (e.g., Eveland et al. 2005; Pasek et al. 2006). After testing six different models on two-wave panel data, Eveland et al. (2005) concluded that American participants’ news use and political discussion led to their political knowledge. Pasek et al. (2006) explored the influences of 12 different uses of mass media and political awareness on civic activity. Their study found that political awareness is highly associated with exposure to informational media. People with higher civic activities are also found to have a higher awareness of politics. Previous researchers found that political awareness had significantly affected people’s political attitudes and behaviors, including voter turnout and political crowdfunding (Zaller 1990; Pasek et al. 2006). Larcinese (2007) found that an increase of one standard deviation from the mean of British voters’ political knowledge raised the probability of voting by at least 5%, with other variables controlled. Baber’s (2020) study identified political awareness as a positive, significant predictor of their intention to participate in political crowdfunding. In line with past research, the following hypothesis was proposed:

Hypothesis 2c (H2c).

Political awareness will influence US citizens’ intention to participate in political crowdfunding.

2.5. Online Community Engagement

Citizens generally surround themselves with individuals who share similar political opinions and attitudes (Huckfeldt et al. 2004). The presence of the Internet has allowed the creation of various platforms for citizens to engage with one another as a community with similar interests; for example, Facebook, which has risen to be the most well-known social media platform, in which people can encounter like-minded individuals to discuss politics (Kushin and Kitchener 2009; Vesnic-Alujevic 2012; Enli and Skogerbø 2013). Towner and Muñoz (2016) suggested that social media platforms are positively linked to Baby Boomers’ political engagement in an online environment.

Engagement to an online community can be defined as the passion of people to contribute as an act that is perceived as beneficial to oneself (Ray et al. 2014). When people are engaged in the community, either online or offline, they are also opening up opportunities for increased knowledge and awareness (Ryu et al. 2005; Malik and Haidar 2020). People are known to be motivated to join the online community because of the shared interest they have with other members (Ridings and Gefen 2006), as well as to acquire and exchange knowledge (Apostolou et al. 2017).

The effect of community engagement has been shown to have an effect on political participation (Conroy et al. 2012; Vissers and Stolle 2014; Hyun and Kim 2015; Kim and Chen 2016). For instance, exposure to like-minded individuals is found to be affecting the political participation of active blog users (Kim and Chen 2016). Using Facebook and Twitter users in South Korea, Hyun and Kim (2015) reported a link between interactive social media use with offline political participation. During the pandemic, young people turned to social media, both as consumers and producers of political content (Booth et al. 2020). According to the same research, young people in the US find election information on social media higher compared to 2018. Therefore, it is interesting to examine the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Online community engagement will influence US citizens’ intention to participate in political crowdfunding.

2.6. Attitude

Attitude is defined as an appraisal measurement that represents a person’s evaluation of the entity in question (Fishbein and Ajzen 1977). Attitude towards crowdfunding plays an important role when people decide whether or not to contribute to a crowdfunding campaign (Kochenash 2016). The relationship between attitude and behavioral intentions has been confirmed by various studies (e.g., Vabø and Hansen 2016) and particularly, in the technology usage intention (e.g., Luqman et al. 2018). Lacan and Desmet (2017) suggested a positive attitude towards the crowdfunding platform significantly increased respondents’ intentions to participate in the campaigns. Shneor and Munim (2019) found that attitude strongly influenced the financial contribution intention in reward-based crowdfunding. Baber (2019a) found that the experience of computer and technology, financial market experience, and influence of reference groups positively contributed to Indians’ attitude towards crowdfunding. Chen et al. (2019) suggested that attitude towards crowdfunding has a positive relationship with the money donations in crowdfunding. Hence, it is posited that:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Attitude towards crowdfunding will influence US citizens’ intention to participate in political crowdfunding.

2.7. Subjective Norm

Subjective norms are people’s perceptions of social pressure from significant others to perform a behavior (Sheeran et al. 1999). The major source of social influence comes from close reference members, such as family members, friends, and neighbors (Wan et al. 2017). Subjective norms are a strong predictor of behavioral intention, working along with attitude (de Vries et al. 1988). Moon and Hwang (2018) defined subjective norm as the extent of influence of an individual’s close reference members on individuals’ decision to participate in crowdfunding. Towner and Muñoz (2016) found that even in virtual relationships and observing the political activities of their reference groups on social media, Baby Boomers no longer feel isolated from online politics and, instead, feel more associated. Baber (2019b) found the influence of family and friend reference groups strongly influences the behavioral intention of an individual to participate in crowdfunding. Some studies established the role of social influence on the judgment to participate in crowdfunding projects (Cecere et al. 2017). So far, the results about the relationship between subjective norms and participation in crowdfunding campaigns are mixed. For example, studies from Moon and Hwang (2018) and Shneor and Munim (2019) found a positive significant relationship between subjective norms and intention, which contradicts with the results of Chen et al. (2019), in the case of donation-based crowdfunding. Therefore, it will be interesting to understand this relationship in the US elections’ context:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Subjective norms about crowdfunding will influence US citizens’ intention to participate in political crowdfunding.

2.8. Perceived Behavioral Control

Perceived behavioral control signifies a subjective degree of control over an action of the behavior itself in the situation and is regarded as the direct predictor of behavioral intention (Ajzen 2002). When a person has significant control over their actions, the individual will have strong intentions to complete a particular behavior (Webb et al. 2013). Self-efficacy and perceived behavioral control can be interchangeably used, both operationally and conceptually, and can strongly predict the intention of an individual (Lee and Kim 2017). Baber (2020) found perceived behavior control insignificant in predicting the intentions of Indian citizens to participate in political crowdfunding. Stevenson et al. (2019) suggested a negative relationship between self-efficacy and the funder’s decision-making performance through the funder’s searching efforts. However, self-efficacy has been found as a significant determinant of financial contribution intention in crowdfunding projects (Shneor and Munim 2019).

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Perceived behavior control about crowdfunding will influence US citizens’ intention to participate in political crowdfunding.

2.9. Social Distancing during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Infectious viruses spread in the community through close contact with infectious persons (Fong et al. 2020). Social distancing and lockdown reduce the transmission and delay the peak by spreading the cases over a long period to relieve stress on the healthcare system (Fong et al. 2020). Lewnard and Lo (2020) stated that it is the responsibility of politicians and state administration to enforce social distancing measures and not to discriminate against anyone for following the public safety rules. However, it is a useful strategy until a vaccine is developed. Social distancing measures include the closing of schools, malls, workplaces, and other gathering places and events (Fong et al. 2020). Krimmer et al. (2020) suggested that elections during the pandemic could increase the number of infections in the population by promoting social interaction in closed spaces. Online set-up during the pre-electoral process is the best solution to mitigate the risk of virus spread (Landman and Splendore 2020).

A survey conducted during national lockdown in 15 European countries revealed that the lockdown increased people’s voting intention (Bol et al. 2021). This is understandable, because during the elections, moving to remote voting is one of the best options available and changes should be made to the electoral process to adapt to a pandemic situation (James 2020). Hence, we believe that social distancing norms in place will enhance the attitude of people towards crowdfunding so that they do not have to participate in offline pre-electoral activities. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis for the first time:

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Social distancing efficacy will influence the attitude of US citizens towards crowdfunding.

3. Method

3.1. Instrument

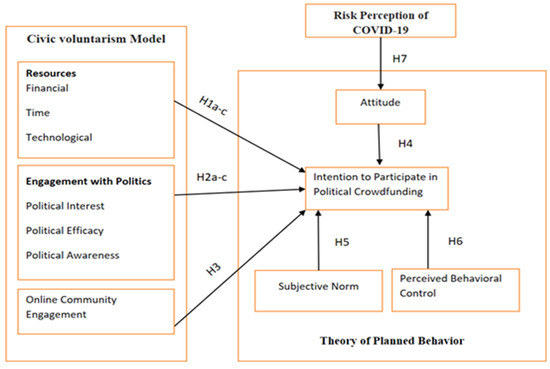

The survey questionnaire was developed based on past studies. The items were adapted and modified to fit into the context of crowdfunding and US politics. The items for the resources (financial, time, and technology) were borrowed from the study of Oni et al. (2017). Other measures include political interest (Bimber 2014), political efficacy (Niemi et al. 1991), political awareness (Bartle 2000; Wang and Shen 2018), online community engagement (Han et al. 2019), attitude (Baber 2020), subjective norms and perceived behavior control (Shneor and Munim 2019), social distancing efficacy (Kleczkowski et al. 2015), and intentions (Kusumarani and Zo 2019). The model of the study was integrated and constructed based on previous studies from Kusumarani and Zo (2019), Oni et al. (2017), and Baber (2020), as shown in Figure 1. As the elections occurred in the middle of a pandemic, the effect of social distancing was an important variable to be tested during the COVID-19 crisis. A record number of people chose to mail in their votes to avoid the risk of catching infection before Election Day, which slowed down the vote count eventually.

Figure 1.

The proposed model of political crowdfunding attitude, intention, and behavior.

3.2. Data Collection

A pilot study of 44 participants was conducted by one co-author among his undergraduate students and colleagues at a public state university in the United States. The feedback of the pilot study and changes were incorporated in the final questionnaire. The questionnaire was published through Amazon Mechanical Turk with a location within the US and a screener was used to make sure that only U.S. citizens filled in the questionnaire. The survey was administered from October 19 to October 27, 2020, before Election Day (November 3) in the United States. We collected around 711 responses; however, after the normalization of data, 529 responses were retained for further analysis. The participants consisted of 63.7% males, 36.1% females, and 0.2% other. The majority of the respondents were White (Non-Hispanic) (73%) followed by Black or African American, Asian or Pacific Islander, and others. The respondents were from the various age groups, making the sample diverse: 20–30 years (44.8%), 31–40 years (26.7%), 41–50 years (15.5%), and above 50 years (13%). The respondents mostly had a 4-year college graduate degree (71.3%) followed by a Master’s degree or professional degree (15.1%). The majority of their annual house income ranged from USD 50,001 to USD 100,000 per year (53.9%), whereas more than one-third fell into the bracket of USD 10,001 to USD 50,000 (35.9%). The respondents had already donated some amount of money to political campaigns for different political parties during this election. Some of them had never donated but the majority of the respondents were very frequent in their political donations, as shown in Appendix A.

To check the non-response bias, the sample was divided into two groups, 264 each after ordering the sample according to the time of response. The first group represents the responses received early and the second group responded late. Non-response bias is the imprecision of the results when people who do not respond to the survey, or who are not part of the sample, might have responded otherwise than those who answered the survey (Maitland et al. 2017). This method is known as the wave test, which holds the assumption that those who respond unwillingly or relatively late are more likely to bear the qualities of non-respondents. An independent sample t-test was conducted on the demographic variables—age and gender—to compare the differences across the two groups. Levene’s test for homogeneity of variances shows that there is no significant difference in terms of homogeneity of variances between the early and late responses for each demographic variable (age-F-value: 0.948, p: 0.576 and gender-F value: 0.011, p: 0.989). Therefore, the collected data sample is not influenced by non-response bias.

3.3. Measurement Model

Partial Least Square (PLS) structural equation modeling (SEM) approach was used to test the hypothesized relationship, using the SmartPLS software. PLS-SEM is convenient for testing a research framework where it is important to test the dependencies of the variable, the structure is complex, and data may lack normality. PLS-SEM is more useful in the earlier phases of theory development, as it helps in exploration and theory development, provides more accurate estimates with small sample sizes, is more likely to result in model convergence when studying many observed and/or latent variables, and it is more suitable when models are complex (Hair et al. 2020). The factor loadings of all thirteen variables were estimated as shown in Table 1. All the values of factor loadings exceeded the accepted minimum value of 0.70 (Hair et al. 2019), except the items of Fin01, Tech01, and Engage05, which were deleted for further analysis.

Table 1.

Measurement Model.

To check the reliability and validity of the items in the constructs, Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability were estimated. All constructs met the recommended threshold value of 0.70 (Hair et al. 2019) as shown in Table 1. Therefore, reliability for all factors is established. To test the validity of data, which means that items measure the variable they were meant to measure. The AVE (Average Variance Extracted) was calculated and all values ranged from 0.549 to 0.840, higher than the acceptable value of 0.50 (Hair et al. 2019). The variance inflation factor (VIF) values help to evaluate the collinearity of the formative indicators. Ideally, the values of VIF should be around 3 or lower (Hair et al. 2019). Hence, our data does not suffer from the multicollinearity problem.

To test the divergent validity of the items, which means that each item measures a different thing from the other items in different constructs, Fornell–Larcker criteria were used to test the divergent validity, as shown in Table 2. The square root of all AVEs on the diagonal is higher than any correlation between constructs; therefore, divergent validity is established (Fornell and Larcker 1981). The HTMT ratio further supported divergent validity as all values are below the acceptable maximum threshold of value 0.85 (Henseler et al. 2014).

Table 2.

Fornell–Larcker Criterion to assess discriminant validity.

4. Results

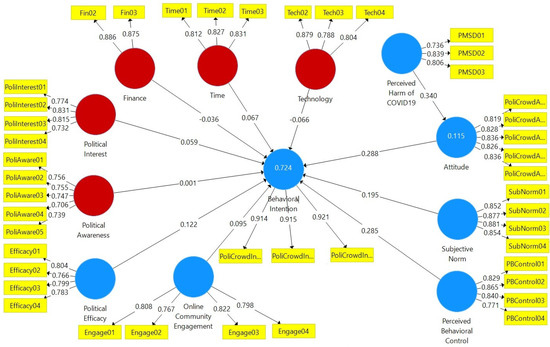

In PLS-SEM, the goodness of fit of the estimated model is assessed differently than covariance-based SEM (CB-SEM). For the robustness of the projected results, we assessed two models—one without the control variable and the latter with them. The latter model included age, gender, and party affiliation as control variables to examine if there will be any change in the relationship. For all the control factors, dummy variables were created, e.g., Democratic member was given ‘1’, Republic affiliation ‘2’, and so on. Most of the hypothesized relationships are statistically significant at 1% and 5% levels. There is a positive effect of political efficacy on intention (β = 0.112, p < 0.05), online community engagement on intention (β = 0.095, p < 0.05), attitude on intention (β = 0.288, p < 0.05), subjective norms on intention (β = 0.195, p < 0.05), perceived behavioral control on intention (β = 0.285, p < 0.05), and social distancing efficacy on attitude (β = 0.340, p < 0.05) (see Table 3). Therefore, our results supported hypotheses H2b, H3, H4, H5, H6, and H7. To further evaluate the goodness of fit of the estimated model, the R2 values of attitude and intention are 0.115, and 0.724, respectively, as shown in Figure 2. This implies that variance in attitude towards crowdfunding and actual behavior are explained by factors other than social distancing efficacy, whereas 72% of the variance in the intentions is explained by the given factors of the study. This indicates that the structural model has moderate explanatory power of predicting variables. The following variables were shown to have no significant influence on the intention: resources (finance, time, technology), political interest, and political awareness. All the positive relationships were retained in the control variable model, except social distancing efficacy, which turned out to be insignificant. Further, no significant influence of three demographic control variables was found on the behavioral intention.

Table 3.

Path coefficients.

Figure 2.

PLS-SEM Estimated model. Blue-colored factors are significant at p < 0.01 & p < 0.5. Red-colored factors are insignificant.

5. Discussion

As one of the first empirical studies, the current research integrated the Civic Volunteerism Model and the Theory of Planned Behavior to examine U.S. citizens’ intention to participate in political crowdfunding in an extraordinary presidential election year, with the global COVID-19 pandemic. Our survey results confirmed the good explanatory power of the TPB in the context of political crowdfunding for U.S. Elections. The findings are consistent with previous studies that applied the TPB to predict crowdfunding (e.g., Kuo and Wu 2014; Moon and Hwang 2018; Shneor and Munim 2019), and in accordance with the most recent study on political crowdfunding in India (Baber 2020). Specifically, our study shows that U.S. participants’ perceived behavioral control, subjective norms, and attitudes toward political crowdfunding positively predicted their intent to participate in political crowdfunding. Future researchers are strongly recommended to incorporate those important factors when investigating U.S. citizens’ intention to donate to political campaigns for elections at local, state, and national levels. In addition, the present study further established the link of attitude–intention–behavior in the context of political crowdfunding, as shown in several meta-analyses of TPB studies (e.g., Armitage and Conner 2001). Moreover, we detected the mediating effects of many key variables on our participants’ political crowdfunding behavior through their intention, including political efficacy, online community engagement, attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, and social distancing efficacy. It is advisable to draw upon the TPB when future electoral studies focus on actual campaign donation behavior. Under the special circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic, U.S. citizens’ political crowdfunding attitudes were positively influenced by their social distancing efficacy. It is not surprising that many American people are more likely to favor online political activities, including political crowdfunding, if they believe firmly that social distancing is a very effective measure to prevent COVID-19 spread and they feel confident in practicing social distancing. Political crowdfunding as a growing trend is further evidenced by the hugely successful online fundraising efforts of Biden’s and Trump’s teams in Election 2020.

On the other hand, our findings for the CVM are not very consistent with previous studies of political participation (e.g., Guo et al. 2021; Kim and Khang 2014) and political crowdfunding (Baber 2020; Kusumarani and Zo 2019). The resources (finance, time, and technologies) did not play an important role for our participants when contributing to political campaigns in the US context. Only one motivation factor—political efficacy—emerged as a positive, significant predictor of our respondents’ political crowdfunding intention, whereas political interest and political awareness are proved to be insignificant. The mobilization component of the CVM is validated by the finding that their online community engagement positively predicted their political crowdfunding intent. As 75.2% of our participants reported to have donated less than USD 100 to political campaigns, financial resources should not be an inhibiting factor for small donors in U.S. political elections. It suggests that many middle-class U.S. citizens can afford political contributions under USD 100, as 53.9% of them reported an annual family income of USD 50,000+. Time is not a problem for political campaign contributions either as Internet technologies have allowed U.S. citizens to transfer their money in a few seconds. Our sample came from Amazon Mechanical Turk workers and we can safely assume that they are familiar with online technologies and social media platforms. Hence, technological skills are not a deal breaker for our respondents to participate in political crowdfunding. Political interest did not influence political crowdfunding intent, which can be partly explained by the fact that a majority of our sample identified as Republicans and Independents closer to the Republican Party (56.5%). Many Republican and Trump voters refrain from expressing their political views in either public or private settings (e.g., Yang et al. 2020) but they feel free to show their support online by contributing funds to Republican and Trump’s campaigns secretly. Good political knowledge or awareness does not seem to be essential for the participation of political crowdfunding, considering that many active online participants of politics are U.S. citizens without a college degree, such as Trump supporters. It is also possible that the direct effects of political interest and political awareness were subsumed or fully mediated the effect of the political efficacy of our participants on their political crowdfunding intent.

As we can apply the TPB to predict U.S. citizens’ political crowdfunding attitude, intent, and behavior, political campaign organizers, communicators, and activists should target their marketing campaigns to those online adults who expressed favorable attitudes and willingness to donate to a political cause or campaign. It is more cost efficient and effective to appeal to them than to recruit other people who have no awareness of political crowdfunding as the conversion rate will be much higher. Inspired by the predictive power of subjective norms in this study, political campaign organizers and communicators should leverage social influence (peer pressure and parental influence) with the help of social media to solicit political campaign donations online. For example, if possible, we can show potential donors how many of their friends on Facebook/Instagram/Twitter/YouTube liked or even donated to a particular political campaign. In addition, online referrals of political fundraisers should be encouraged as we know that like-minded individuals tend to cluster in online communities. Because of social distancing and stay-at-home recommendations during the COVID-19 pandemic, political actors were forced to move online for many political activities, such as campaigning and fundraising. The new political norm seems to have been widely accepted by the American people. Therefore, the conformity appeal of doing the right thing (expected by others) might work well in political marketing campaigns. At the same time, we should not overplay the social influence card, as our participants like to feel that they are in control. It will be a good idea to provide prospective donors with a variety of choices, such as in-kind contributions, small amounts (USD 1 to USD 5), and the purchase of merchandising products. The fundraisers that are intended to empower potential donors should work better than normal ones if they allow people to decide when, where, and how to contribute to any political campaign.

5.1. Research Implications

To broaden the target audience of online political fundraising efforts, campaign organizers, communicators, and activists should monitor and recruit active participants of online groups, forums, and listservs to participate in their political crowdfunding and to serve as viral agents for their digital ads. We know that online community engagement positively predicts U.S. citizens’ political crowdfunding intent. It also suggests that online social networks and/or online social capital might be instrumental for communicating political interests among the public, which traditional media was doing before. Political marketing campaigns and fundraisers will be more effective and efficient if organizers and activists could seek out social media micro-influencers who have accumulated a wide network of friends or followers. Thus, communication and promotion will reach a large audience. Political efficacy turns out to be an important predictor of U.S. citizens’ political crowdfunding intent. Political campaign organizers, communicators, and activists should care about whether their potential small-dollar donors are well informed and confident about political participation. Political marketing campaigns would work better if they were informative, inspiring, and encouraging. We should not underestimate the wisdom of our target audience and we should assure them that their campaign contributions will make a huge difference in political elections. Political campaign organizers, communicators, and activists should feel encouraged for their future political crowdfunding efforts, as financial resources, time, and technologies are not really barriers for prospective small donors and political crowdfunding, indeed, can help us democratize the political process. Thus, they should cover all ground and try to reach people from all walks of life. Television, radio, out-of-home media, and print media should be considered as marketing platforms, in addition to the Internet and social media.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

Although previous studies established that the reliability and validity of Amazon Mechanical Turk samples are better than student samples and convenience samples (e.g., Sheehan 2017), our sample is not a nationally representative sample of U.S. citizens and future researchers should try to recruit participants from a national probability sample or at least a national panel.

From CVM’s perspective, only two factors are found to be significant, while other factors, such as perceived resources, political interest, and political awareness, were insignificant. Future studies should dig deeper on why this happens and compare it with a post-pandemic and non-pandemic setting.

Future studies should incorporate additional predictors, such as news media use, social media use, online social network size, online social capital, and previous political experiences. Further research should be conducted to investigate whether the integrated model predicts citizen’s actual behavior of political crowdsourcing, such as their online donation behavior or their administration of online political fund raisers.

Longitudinal studies can be conducted to assess the long-term effects of those key factors on people’s political crowdfunding attitude, intent, and behavior. Experimental research should be undertaken to test the antecedents of political crowdfunding attitude, intent, and behavior, such as the polling averages of candidates, the framing of political issues, and different rational and emotional appeals.

6. Conclusions

After testing an integrated model based on the TPB and CVM, the present study demonstrated that the TPB model performed very well in predicting U.S. citizens’ political crowdfunding attitude and intent, whereas two important components of the CVM also emerged as key contributors—the motivation (political efficacy) and mobilization components (online community engagement).

Political crowdfunding appears to have become an alternative funding resource in political finance. During the pandemic, this sector was one of the many sectors that was affected by the changes. Nevertheless, there are only limited number of studies that discuss the effect through a political crowdfunding lens.

Throughout our literature review, we showed that the changes have the potential to affect people’s intention to participate in political crowdfunding. However, our results are somehow mixed, as not all aspects significantly affected people’s intentions to engage in political crowdfunding.

The COVID-19 pandemic might have provided the friendliest environment for online political crowdfunding and campaigning. Our result shows that social distancing measures during the COVID-19 pandemic significantly improved people’s attitude toward crowdfunding. Hence, we infer that political crowdfunding will thrive during any pandemic or similar crises. We sincerely believe that online political crowdfunding and campaigning can help democratize the political process and participation for all the people who have the sacred right to vote.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.B. and R.K.; methodology, H.B., and H.Y.; formal analysis, H.B.; investigation, H.B. and H.Y.; resources, H.B., R.K. and H.Y.; data curation, H.B. and H.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, H.B., R.K. and H.Y.; writing—review and editing, H.B., R.K. and H.Y.; visualization, H.B.; supervision, H.B.; project administration, H.B. and H.Y.; funding acquisition, H.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Abu Dhabi School of Management.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Appalachian State University (IRB #21-0052 and 09/27/2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are not publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

| Frequency | Percent | ||

| Gender | Male | 337 | 63.7 |

| Female | 191 | 36.1 | |

| Race | American Indian or Alaska native | 6 | 1.1 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 48 | 9.1 | |

| Black or African American | 49 | 9.3 | |

| White (Non-Hispanic) | 389 | 73.5 | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 34 | 6.4 | |

| Racially mixed | 2 | 0.4 | |

| Other | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Age | 20–30 | 237 | 44.8 |

| 31–40 | 141 | 26.7 | |

| 41–50 | 82 | 15.5 | |

| Above 50 | 69 | 13.0 | |

| Education | Less than high school | 3 | 0.6 |

| High School graduate | 29 | 5.5 | |

| Some college or 2 year college | 35 | 6.6 | |

| 4 year college graduate | 377 | 71.3 | |

| Masters degree or professional degree | 80 | 15.1 | |

| Doctorate | 5 | 0.9 | |

| Family Income | Less than $10,000 | 11 | 2.1 |

| $10,001 to $50,000 | 190 | 35.9 | |

| $50,001 to $100,000 | 285 | 53.9 | |

| $100,001 to $150,000 | 40 | 7.6 | |

| More than $150,000 | 3 | 0.6 | |

| Party Affiliation | A Democrat | 175 | 33.1 |

| A Republican | 275 | 52.0 | |

| An Independent closer to the Democratic Party | 38 | 7.2 | |

| An Independent closer to the Republican Party | 24 | 4.5 | |

| An Independent closer to Neither Party | 15 | 2.8 | |

| Other | 2 | 0.4 | |

| Internet Use | 1 to 30 min | 7 | 1.3 |

| 31 min to 1 h | 18 | 3.4 | |

| 1 to 1.5 h | 46 | 8.7 | |

| 1.5 to 2 h | 67 | 12.7 | |

| 2 to 2.5 h | 84 | 15.9 | |

| 2.5 to 3 h | 52 | 9.8 | |

| 3 to 3.5 h | 45 | 8.5 | |

| 3.5 to 4 h | 48 | 9.1 | |

| 4 to 4.5 h | 31 | 5.9 | |

| 4.5 to 5 h | 27 | 5.1 | |

| More than 5 h | 104 | 19.7 | |

| During 2020, how much have you donated to political campaigns? | |||

| Less than 20 dollars | 70 | 13.2 | |

| 21–40 dollars | 61 | 11.5 | |

| 41–60 dollars | 82 | 15.5 | |

| 61–80 dollars | 81 | 15.3 | |

| 81–100 dollars | 104 | 19.7 | |

| 101–120 dollars | 62 | 11.7 | |

| 121–140 dollars | 27 | 5.1 | |

| 141–160 dollars | 18 | 3.4 | |

| 161–180 dollars | 8 | 1.5 | |

| 181–200 dollars | 7 | 1.3 | |

| More than 200 dollars | 9 | 1.7 | |

| During 2020, how often have you made a campaign contribution online? | |||

| Never | 51 | 9.6 | |

| About once a month | 140 | 26.5 | |

| Several times a month, but not every week | 103 | 19.5 | |

| About once a week | 107 | 20.2 | |

| Several times a week | 98 | 18.5 | |

| Every day | 30 | 5.7 | |

Appendix B

| Item |

| Finance |

| I have money to access the internet |

| I have money to participate in political crowdfunding |

| I have money to donate for political activities. |

| Time |

| I have free time to participate in politics |

| I can spare time from my work to engage in the political process |

| I have time to engage in political crowdfunding campaigns |

| Technology |

| I know how to use a computer. |

| I use social media to participate in political discussions. |

| I know how to surf the Internet |

| I check political news and information through the internet |

| Political Interest |

| I engage in a discussion on political issues with friends/people around me. |

| I prefer to give my views on political issues. |

| I like to take part in the talk on political issues of my state and country. |

| I am mostly concerned about political issues of my state and country. |

| Political Efficacy |

| I consider myself well-qualified to participate in politics. |

| I feel that I have a pretty good understanding of the important political issues facing our country. |

| I feel that I could do as good a job in public office as most other people. |

| I think that I am better informed about politics and government than most people |

| Political Awareness |

| I have enough knowledge of the US politics |

| I am aware of the current political situation of the United States. |

| I have knowledge about the political parties - the Democratic Party and the Republican Party. |

| I know the number of seats in the United States House of Representatives. |

| I know the process of electing the local and national government. |

| Online Community Engagement |

| It is important for me to participate in the online community. |

| I give a lot of time and efforts to participating in the online community |

| I am highly interested in participating in online community discussions. |

| I can express myself better when I engage in the online community. |

| I support or disagree with other members of the online community. |

| Attitude |

| I like to contribute towards political crowdfunding campaigns. |

| It makes me feel good to contribute to political crowdfunding campaigns. |

| I believe it is beneficial for me contributing to political crowdfunding campaigns. |

| I have a positive perception of contributing to political crowdfunding campaigns. |

| I think it will be suitable for me to contribute to political crowdfunding campaigns. |

| Subjective Norm |

| People who are important to me think that I should contribute to political crowdfunding campaigns. |

| People who influence my behavior encourage me to contribute to political crowdfunding campaigns. |

| My family thinks that I should contribute to political crowdfunding campaigns. |

| My friends think that I should contribute to political crowdfunding campaigns. |

| Perceived Behavioral Control |

| My participation in political crowdfunding campaigns is within my control. |

| I think I will be able to contribute to political crowdfunding campaigns. |

| It is entirely my choice to contribute to political crowdfunding campaigns. |

| It is completely up to me whether or not I contribute to political crowdfunding campaigns. |

| Social distancing efficacy |

| To engage in social distancing (e.g., by avoiding public transport and social events) will lessen my chance of developing an infectious disease. |

| I feel it would be necessary to engage in social distancing during times of infectious diseases. |

| I feel confident in my ability to engage in social distancing during times of infectious diseases. |

| Intention |

| I am interested in participating in political crowdfunding campaigns to support candidates for election soon. |

| There is a big chance that I will donate to political crowdfunding campaigns to support candidates in the next elections. |

| I certainly intend to contribute to political crowdfunding campaigns to support candidates for the next elections. |

References

- Ajzen, Icek. 2002. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 32: 665–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolou, Barbara, France Belanger, and Ludwig C. Schaupp. 2017. Online communities: Satisfaction and continued use intention. Information Research 22: 774. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage, Christopher J., and Mark Conner. 2001. Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A Meta-Analytic Review. British Journal of Social Psychology 40: 471–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baber, Hasnan. 2019a. Factors Underlying Attitude Formation towards Crowdfunding in India. International Journal of Financial Research 10: 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baber, Hasnan. 2019b. Subjective Norms and Intention—A Study of Crowdfunding in India. Research in World Economy 10: 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baber, Hasnan. 2020. Intentions to Participate in Political Crowdfunding- from the Perspective of Civic Voluntarism Model and Theory of Planned Behavior. Technology in Society 63: 101435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baber, Hasnan, and Mina Fanea-Ivanovici. 2021. Motivations Behind Backers’ Contributions In Reward-Based Crowdfunding For Movies And Web Series. International Journal of Emerging Markets, ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Tom P., and Claes H. De Vreese. 2011. Good news for the future? Young people, Internet use, and political participation. Communication Research 38: 451–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barrios, John, and Yael Hochberg. 2020. Risk Perception through the Lens of Politics in the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic. (No. w27008). National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartle, John. 2000. Political Awareness, Opinion Constraint and the Stability of Ideological Positions. Political Studies 48: 467–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimber, Bruce. 2014. Digital Media in the Obama Campaigns of 2008 and 2012: Adaptation to the Personalized Political Communication Environment. Journal of Information Technology & Politics 11: 130–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bol, Damien, Marco Giani, André Blais, and Peter John Loewen. 2021. The effect of COVID-19 lockdowns on political support: Some good news for democracy? European Journal of Political Research 60: 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, Ruby Belle, Emma Tombaugh, Abby Kiesa, Kristian Lundberg, and Alison Cohen. 2020. Young People Turn to Online Political Engagement During COVID-19. Available online: https://circle.tufts.edu/latest-research/young-people-turn-online-political-engagement-during-covid-19 (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Brady, Henry E., Sidney Verba, and Kay Lehman Schlozman. 1995. Beyond SES: A Resource Model of Political Participation. American Political Science Review 89: 271–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campante, Filipe, Ruben Durante, and Francesco Sobbrio. 2017. Politics 2.0: The Multifaceted Effect of Broadband Internet on Political Participation. Journal of the European Economic Association 16: 1094–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carter, Lemuria D. 2006. Political Participation in a Digital Age: An Integrated Perspective on the Impacts of the Internet on Voter Turnout. Ph.D. thesis, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Cecere, Grazia, Fabrice Le Guel, and Fabrice Rochelandet. 2017. Crowdfunding and Social Influence: An Empirical Investigation. Applied Economics 49: 5802–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Chao, Yu Bai, and Rui Wang. 2019. Online Political Efficacy and Political Participation: A Mediation Analysis Based on the Evidence from Taiwan. New Media & Society 21: 1667–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Robert L., Annamaria Lusardi, and Olivia S. Mitchell. 2021. Financial fragility during the COVID-19 Pandemic. In AEA Papers and Proceedings. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research, vol. 111, pp. 292–96. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, Harold D., and Alan C. Acock. 1989. National Elections and Political Attitudes: The Case of Political Efficacy. British Journal of Political Science 19: 551–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogburn, Derrick L., and Fatima K. Espinoza-Vasquez. 2011. From Networked Nominee to Networked Nation: Examining the Impact of Web 2.0 and Social Media on Political Participation and Civic Engagement in the 2008 Obama Campaign. Journal of Political Marketing 10: 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colizzi, Marco, Elena Sironi, Federico Antonini, Marco Luigi Ciceri, Chiara Bovo, and Leonardo Zoccante. 2020. Psychosocial and behavioral impact of COVID-19 in autism spectrum disorder: An online parent survey. Brain Sciences 10: 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, Meredith, Jessica T. Feezell, and Mario Guerrero. 2012. Facebook and political engagement: A study of online political group membership and offline political engagement. Computers in Human Behavior 28: 1535–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culberson, Tyler, Michael P. McDonald, and Suzanne M. Robbins. 2018. Small Donors in Congressional Elections. American Politics Research 47: 970–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, Hein, Margo Dijkstra, and Piet Kuhlman. 1988. Self-Efficacy: The Third Factor besides Attitude and Subjective Norm as a Predictor of Behavioural Intentions. Health Education Research 3: 273–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enli, Gunn Sara, and Eli Skogerbø. 2013. Personalized campaigns in party-centred politics: Twitter and Facebook as arenas for political communication. Information, Communication & Society 16: 757–74. [Google Scholar]

- Eveland, William P., Andrew F. Hayes, Dhavan V. Shah, and Nojin Kwak. 2005. Understanding the Relationship between Communication and Political Knowledge: A Model Comparison Approach Using Panel Data. Political Communication 22: 423–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkowski, Andrzej, and Magdalena Jabłońska. 2019. Moderators and Mediators of Framing Effects in Political Marketing: Implications for Political Brand Management. Journal of Political Marketing 19: 34–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanea-Ivanovici, Mina, and Hasnan Baber. 2021. Crowdfunding Model For Financing Movies And Web Series. International Journal of Innovation Studies 5: 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, Martin, and Icek Ajzen. 1977. Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Philosophy and Rhetoric, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Fong, Min W., Huizhi Gao, Jessica Y. Wong, Jingyi Xiao, Eunice Y. C. Shiu, Sukhyun Ryu, and Benjamin J. Cowling. 2020. Nonpharmaceutical Measures for Pandemic Influenza in Nonhealthcare Settings—Social Distancing Measures. Emerging Infectious Diseases 26: 976–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, Claes, and David F. Larcker. 1981. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research 18: 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Junpeng, Na Liu, Yi Wu, and Chunxin Zhang. 2021. Why Do Citizens Participate on Government Social Media Accounts during Crises? A Civic Voluntarism Perspective. Information & Management 58: 103286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Jose F., Jr., Matt C. Howard, and Christian Nitzl. 2020. Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. Journal of Business Research 109: 101–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., Jeffrey J. Risher, Marko Sarstedt, and Christian M. Ringle. 2019. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review 31: 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Jeongsoo, Mina Jun, and Miyea Kim. 2019. Impact of Online Community Engagement on Community Loyalty and Social Well-Being. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal 47: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heberlig, Eric, and Bruce Larson. 2020. Gender and Small Contributions: Fundraising by the Democratic Freshman Class of 2018 in the 2020 Election. Society 57: 534–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, Jörg, Christian M. Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. 2014. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 43: 115–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huckfeldt, Robert, Jeanette Morehouse Mendez, and Tracy Osborn. 2004. Disagreement, Ambivalence, and Engagement: The Political Consequences of Heterogeneous Networks. Political Psychology 25: 65–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, Ki Deuk, and Jinhee Kim. 2015. Differential and Interactive Influences on Political Participation by Different Types of News Activities and Political Conversation through Social Media. Computers in Human Behavior 45: 328–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igra, Mark, Nora Kenworthy, Cadence Luchsinger, and Jin-Kyu Jung. 2021. Crowdfunding as a response to COVID-19: Increasing inequities at a time of crisis. Social Science & Medicine 282: 114105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, Toby S. 2020. New Development: Running Elections during a Pandemic. Public Money & Management 41: 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenski, Kate, and Natalie Jomini Stroud. 2006. Connections between Internet Use and Political Efficacy, Knowledge, and Participation. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 50: 173–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairiza, Fajrina, and Bevaola Kusumasari. 2020. Analyzing Political Marketing in Indonesia: A Palm Oil Digital Campaign Case Study. Forest and Society 4: 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Yeojin, and Hyoungkoo Khang. 2014. Revisiting Civic Voluntarism Predictors of College Students’ Political Participation in the Context of Social Media. Computers in Human Behavior 36: 114–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Yonghwan, and Hsuan-Ting Chen. 2016. Social Media and Online Political Participation: The Mediating Role of Exposure to Cross-Cutting and like-Minded Perspectives. Telematics and Informatics 33: 320–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirbiš, Andrej, Sergej Flere, Darko Friš, Marina Tavčar Krajnc, and Tina Cupar. 2017. Predictors of Conventional, Protest, and Civic Participation among Slovenian Youth: A Test of the Civic Voluntarism Model. International Journal of Sociology 47: 182–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleczkowski, Adam, Savi Maharaj, Susan Rasmussen, Lynn Williams, and Nicole Cairns. 2015. Spontaneous Social Distancing in Response to a Simulated Epidemic: A Virtual Experiment. BMC Public Health 15: 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koch, Jascha-Alexander, and Michael Siering. 2019. The recipe of successful crowdfunding campaigns. Electronic Markets 29: 661–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochenash, Cara R. 2016. Mass Appeal: Social Media Marketing and Crowdfunding among Social Enterprises in California. Ph.D. dissertation, State University of New York at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Konhäusner, Peter, Bing Shang, and Dan-Cristian Dabija. 2021a. Application of the 4Es in Online Crowdfunding Platforms: A Comparative Perspective of Germany and China. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 14: 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konhäusner, Peter, Marius Thielmann, Veronica Câmpian, and Dan-Cristian Dabija. 2021b. Crowdfunding for Independent Print Media: E-Commerce, Marketing, and Business Development. Sustainability 13: 11100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krimmer, Robert, David Duenas-Cid, and Iuliia Krivonosova. 2020. Debate: Safeguarding Democracy during Pandemics. Social Distancing, Postal, or Internet Voting—the Good, the Bad or the Ugly? Public Money & Management 41: 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Ying-Feng, and Chung-Hsien Wu. 2014. Understanding the drivers of sponsors’ intentions in online crowdfunding: A model development. Paper presented at 12th International Conference on Advances in Mobile Computing and Multimedia, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, December 8–10; pp. 433–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kushin, Matthew J., and Kelin Kitchener. 2009. Getting Political On Social Network Sites: Exploring Online Political Discourse on Facebook. First Monday, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumarani, Riri, and Hangjung Zo. 2019. Why People Participate in Online Political Crowdfunding: A Civic Voluntarism Perspective. Telematics and Informatics 41: 168–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacan, Camille, and Pierre Desmet. 2017. Does the Crowdfunding Platform Matter? Risks of Negative Attitudes in Two-Sided Markets. Journal of Consumer Marketing 34: 472–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landman, Todd, and Luca Di Splendore. 2020. Pandemic Democracy: Elections and Covid-19. Journal of Risk Research 23: 1060–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larcinese, Valentino. 2007. Does Political Knowledge Increase Turnout? Evidence from the 1997 British General Election. Public Choice 131: 387–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Le Masurier, Megan. 2012. Independent Magazines and the Rejuvenation of Print. International Journal of Cultural Studies 15: 383–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Seungwoo John, and Hyelin Lina Kim. 2017. Roles of Perceived Behavioral Control and Self-Efficacy to Volunteer Tourists’ Intended Participation via Theory of Planned Behavior. International Journal of Tourism Research 20: 182–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Shin Haeng. 2016. Digital Democracy in Asia: The Impact of the Asian Internet on Political Participation. Journal of Information Technology & Politics 14: 62–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonhard, Larissa, Veronika Karnowski, and Anna Sophie Kümpel. 2020. Online and (the Feeling of Being) Informed: Online News Usage Patterns and Their Relation to Subjective and Objective Political Knowledge. Computers in Human Behavior 103: 181–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin-Waldman, Oren M. 2013. Income, Civic Participation and Achieving Greater Democracy. The Journal of Socio-Economics 43: 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewnard, Joseph A., and Nathan C. Lo. 2020. Scientific and ethical basis for social-distancing interventions against COVID-19. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 20: 631–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Yang, and Jan E. Mutchler. 2020. Older adults and the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Aging & Social Policy 32: 477–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Xiaoqiang, Jianfeng Zhou, Li Chen, Yang Yang, and Jianguo Tan. 2020. Impact of COVID-19 epidemic on live online dental continuing education. European Journal of Dental Education 24: 786–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luqman, Adeel, Ayesha Masood, and Ahmed Ali. 2018. An SDT and TPB-Based Integrated Approach to Explore the Role of Autonomous and Controlled Motivations in ‘SNS Discontinuance Intention’. Computers in Human Behavior 85: 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitland, Aaron, Amy Lin, David Cantor, Mike Jones, Richard P. Moser, Bradford W. Hesse, Terisa Davis, and Kelly D. Blake. 2017. A nonresponse bias analysis of the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS). Journal of Health Communication 22: 545–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, Zunera, and Sham Haidar. 2020. Online Community Development through Social Interaction—K-Pop Stan Twitter as a Community of Practice. Interactive Learning Environments, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollick, Ethan. 2014. The Dynamics of Crowdfunding: An Exploratory Study. Journal of Business Venturing 29: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moon, Younghwan, and Junseok Hwang. 2018. Crowdfunding as an Alternative Means for Funding Sustainable Appropriate Technology: Acceptance Determinants of Backers. Sustainability 10: 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Niemi, Richard G., Stephen C. Craig, and Franco Mattei. 1991. Measuring Internal Political Efficacy in the 1988 National Election Study. American Political Science Review 85: 1407–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nygård, Mikael, and Gunborg Jakobsson. 2013. Political participation of older adults in Scandinavia-the civic voluntarism model revisited? A multi-level analysis of three types of political participation. International Journal of Ageing and Later Life 8: 65–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oni, Aderonke A., Samuel Oni, Victor Mbarika, and Charles K. Ayo. 2017. Empirical Study of User Acceptance of Online Political Participation: Integrating Civic Voluntarism Model and Theory of Reasoned Action. Government Information Quarterly 34: 317–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasek, Josh, Kate Kenski, Daniel Romer, and Kathleen Hall Jamieson. 2006. America’s Youth and Community Engagement. Communication Research 33: 115–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, Rabia Karakaya. 2005. The Internet and political participation: Exploring the explanatory links. European Journal of Communication 20: 435–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, Weina, Masahiro Yamamoto, and Shan Xu. 2016. Media Multitasking during Political News Consumption: A Relationship with Factual and Subjective Political Knowledge. Computers in Human Behavior 56: 352–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, Soumya, Sung S. Kim, and James G. Morris. 2014. The Central Role of Engagement in Online Communities. Information Systems Research 25: 528–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, Guillem, Marc Guinjoan, and Eva Anduiza. 2020. Empowered and Enraged: Political Efficacy, Anger and Support for Populism in Europe. European Journal of Political Research 59: 797–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridings, Catherine M., and David Gefen. 2006. Virtual Community Attraction: Why People Hang out Online. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 10: JCMC10110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, Jessica A. 2008. A National Study Predicting Licensed Social Workers’ Levels of Political Participation: The Role of Resources, Psychological Engagement, and Recruitment Networks. Social Work 53: 347–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, Chungsuk, Yong Jin Kim, Abhijit Chaudhury, and H. Raghav Rao. 2005. Knowledge acquisition via three learning processes in enterprise information portals: Learning-by-investment, learning-by-doing, and learning-from-others. MIS Quarterly 29: 245–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sayedi, Amin, and Marjan Baghaie. 2017. Crowdfunding as a Marketing Tool. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, Kim Bartel. 2017. Crowdsourcing Research: Data Collection with Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Communication Monographs 85: 140–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, Paschal, Paul Norman, and Sheina Orbell. 1999. Evidence That Intentions Based on Attitudes Better Predict Behaviour than Intentions Based on Subjective Norms. European Journal of Social Psychology 29: 403–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, Jill. 2015. Online petitions in Australia: Information, opportunity and gender. Australian Journal of Political Science 50: 480–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shneor, Rotem, and Ziaul Haque Munim. 2019. Reward Crowdfunding Contribution as Planned Behaviour: An Extended Framework. Journal of Business Research 103: 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, Regan M., Michael P. Ciuchta, Chaim Letwin, Jenni M. Dinger, and Jeffrey B. Vancouver. 2019. Out of control or right on the money? Funder self-efficacy and crowd bias in equity crowdfunding. Journal of Business Venturing 34: 348–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tausch, Nicole, Julia C. Becker, Russell Spears, Oliver Christ, Rim Saab, Purnima Singh, and Roomana N. Siddiqui. 2011. Explaining Radical Group Behavior: Developing Emotion and Efficacy Routes to Normative and Nonnormative Collective Action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 101: 129–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The Straits Times. 2017. Tsang raises over $500k for election through crowdfunding. Straitstimes. Available online: http://www.straitstimes.com/asia/east-asia/tsang-raises-over-500k-for-election-through-crowdfunding (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- Tolbert, Caroline J., and Ramona S. McNeal. 2003. Unraveling the effects of the Internet on political participation? Politsical Research Quarterly 56: 175–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towner, Terri L., and Caroline Lego Muñoz. 2016. Baby Boom or Bust? the New Media Effect on Political Participation. Journal of Political Marketing 17: 32–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, Nam-Hyun. 2018. Effectiveness of Celebrity Endorsement of Political Candidates. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal 46: 1585–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vabø, Mette, and Håvard Hansen. 2016. Purchase Intentions for Domestic Food: A Moderated Tpb-Explanation. British Food Journal 118: 2372–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verba, Sidney, Kay Lehman Schlozman, and Henry E. Brady. 1995. Voice and Equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesnic-Alujevic, Lucia. 2012. Political participation and web 2.0 in Europe: A case study of Facebook. Public Relations Review 38: 466–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vissers, Sara, and Dietlind Stolle. 2014. Spill-over effects between Facebook and on/offline political participation? Evidence from a two-wave panel study. Journal of Information Technology & Politics 11: 259–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Calvin, Geoffrey Qiping Shen, and Stella Choi. 2017. Experiential and Instrumental Attitudes: Interaction Effect of Attitude and Subjective Norm on Recycling Intention. Journal of Environmental Psychology 50: 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Tianjiao, and Fei Shen. 2018. Perceived party polarization, news attentiveness, and political participation: A mediated moderation model. Asian Journal of Communication 28: 620–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, Dave, Geoffrey N. Soutar, Tim Mazzarol, and Patricia Saldaris. 2013. Self-Determination Theory and Consumer Behavioural Change: Evidence from a Household Energy-Saving Behaviour Study. Journal of Environmental Psychology 35: 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Hongwei, and Jean L. DeHart. 2016. Social Media Use and Online Political Participation among College Students during the US Election 2012. Social Media + Society 2: 205630511562380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, Hongwei, Newly Paul, and Jean L. DeHart. 2020. Social Media Uses, Political and Civic Participation in U.S. Election 2016. The Journal of Social Media in Society 9: 275–305. [Google Scholar]

- Zaller, John. 1990. Political awareness, elite opinion leadership, and the mass survey response. Social Cognition 8: 125–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).