Untangling Factors Influencing Women Entrepreneurs’ Involvement in Tourism and Its Impact on Sustainable Tourism Development

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Background of the Study

1.2. Problem Statement

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Support and Hypotheses’ Development

2.2. Tourism Involvement

2.3. Perceptions of Women’s Work and Tourism Involvement

2.4. Self-Efficacy and Tourism Involvement

2.5. Empowering Leadership and Tourism Involvement

2.6. Psychological Empowerment and Tourism Involvement

2.7. Tourism Involvement and Sustainable Tourism Development

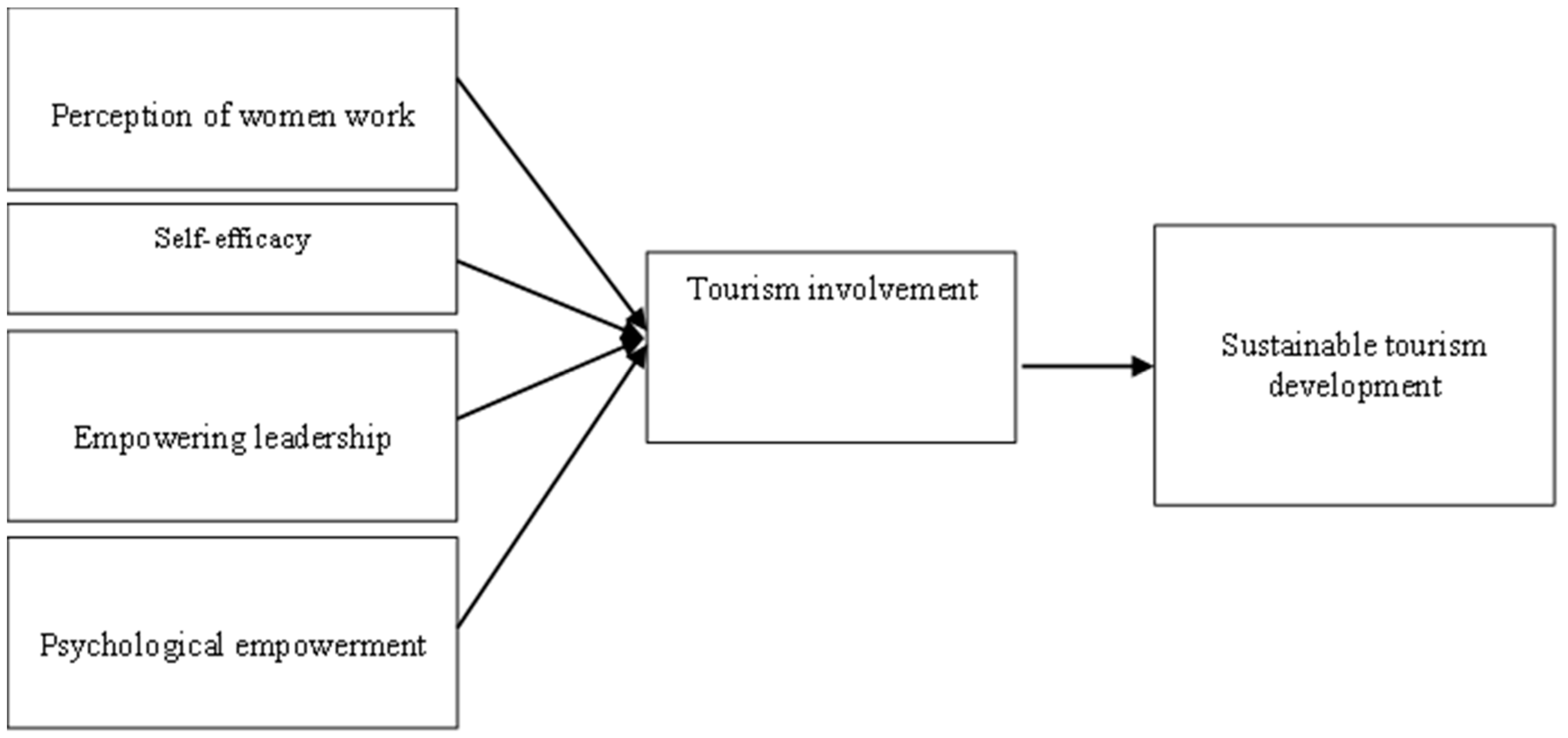

2.8. Research Framework

3. Methodology

3.1. Measures

3.2. Data Collection and Sampling

3.3. Demographic Characteristics

3.4. Common Method Bias (CMB)

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Statistical Analysis and Results

4.2. Measurement Model Analysis

4.3. Structural Model Analysis

4.3.1. Descriptive and Correlation Analysis

4.3.2. Regression Model Test

4.3.3. The Predictive Relevance of the Study Model

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Theoretical and Managerial Implications

8. Limitations and Future Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Items |

|---|---|

| Perception of Women Work | |

| PWW1 | Women’s work in tourism is acceptable in the community. |

| PWW2 | Women’s work in tourism does not conflict with cultural norms and traditions in the community. |

| PWW3 | Women’s work in the tourism public sector is more accepted compared in the private sector by the community. |

| PWW4 | It is widely believed that the community perceives women’s work in tourism has a negative effect on their families. |

| PWW5 | It is widely believed the community perceives certain tourism jobs are more suitable for women than men |

| Self-efficacy | |

| SE1 | I will be able to achieve most of the goals that I have set for myself. |

| SE2 | When facing difficult tasks, I am certain that I will accomplish them. |

| SE3 | In general, I can obtain outcomes that are important to me. |

| SE4 | I believe I can succeed at most any endeavor to which I set my mind. |

| SE5 | I will be able to successfully overcome many challenges. |

| SE6 | I am confident that I can perform effectively on many different tasks. |

| SE7 | Even when things are tough, I can perform quite well. |

| Empowering Leadership | |

| EL1 | My leaders assign me responsibility |

| EL2 | My leader encourages me to take initiative |

| EL3 | My leader listens to me |

| Psychological empowerment | |

| EL1 | I am proud to be a resident of a tourist destination country. |

| EL2 | I feel special because individuals travel to see my country’s attractions. |

| EL3 | I feel proud to share the unique culture of my country with tourists. |

| EL4 | Tourism helps women to have self-esteem and be independent. |

| Tourism Involvement | |

| TI1 | I am pleased to be involved in tourism activities. |

| TI2 | I consider tourism activities to be important |

| T13 | I get upset when participation in a tourism activity is poor. |

| T14 | I am feeling a bit lost when making choices from a variety of tourism activities. |

| TI5 | Choosing a tourism activity is rather complicated. |

| Sustainable Tourism Development | |

| STD1 | I am able to do property-related decisions |

| STD2 | I am confident to make tourism business planning related decisions |

| STD3 | I believe be able to make family and business tourism-related decisions |

References

- Abou-Shouk, Mohamed A., Maryam Taha Mannaa, and Ahmed Mohamed Elbaz. 2021. Women’s empowerment and tourism development: A cross-country study. Tourism Management Perspectives 37: 100782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuhjeeleh, Mohammad. 2019. Rethinking tourism in Saudi Arabia: Royal vision 2030 perspective. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure 8: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Aghazamani, Yeganeh, Deborah Kerstetter, and Pete Allison. 2020. Women’s perceptions of empowerment in Ramsar, a tourism destination in northern Iran. Women’s Studies International Forum 79: 102340. Available online: https://pennstate.pure.elsevier.com/en/publications/womens-perceptions-of-empowerment-in-ramsar-a-tourism-destination (accessed on 23 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Ahearne, Michael, John Mathieu, and Adam Rapp. 2005. To empower or not to empower your sales force? An empirical examination of the influence of leadership empowerment behavior on customer satisfaction and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology 90: 945–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alasgah, Amnah A., and Eman S. Rizk. 2021. Empowering Saudi women in the tourism and management sectors according to the Kingdom’s 2030 vision. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhabidi, Mariam. 2013. Saudi Women Entrepreneur Over Coming Barriers in AL Khober. Arizona State University. Available online: https://keep.lib.asu.edu/items/152022 (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Al-Qahtani, Maleeha Mohammed, Tarek Tawfik Alkhateeb, Haider Mahmood, Manal Abdalla Abdalla, and Thikkryat Jebril Qaralleh. 2020. The role of the academic and political empowerment of women in economic, social and managerial empowerment: The case of Saudi Arabia. Economies 8: 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrwajfah, Moayad Mohammad, Fernando Almeida-García, and Rafael Cortés-Macías. 2020. Females’ perspectives on tourism’s impact and their employment in the sector: The case of Petra, Jordan. Tourism Management 78: 104069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsawafi, Abdulaziz Mohammed. 2016. Exploring the challenges and perceptions of Al Rustaq College of Applied Sciences students towards Omani women’s empowerment in the tourism sector. Tourism Management Perspectives 20: 246–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshuwaikhat, Habib, and Ishak Mohammed. 2017. Sustainability matters in national development visions-Evidence from Saudi Arabia’s Vision for 2030. Sustainability 9: 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amundsen, Stein, and Øyvind L. Martinsen. 2014. Empowering leadership: Construct clarification, conceptualization, and validation of a new scale. The Leadership Quarterly 25: 487–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arshad, Muhammad, Neelam Qasim, Omer Farooq, and John Rice. 2021. Empowering leadership and employees’ work engagement: A social identity theory perspective. Management Decision 60: 1218–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Albert. 1977. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review 84: 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basaffar, Amal A., Linda S. Niehm, and Robert Bosselman. 2018. Saudi Arabian Women In entrepreneurship, challenges, opportunities and potential. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship 23: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boley, B. Bynum, and Nancy Gard McGehee. 2014. Measuring empowerment: Developing and validating the resident empowerment through tourism scale (RETS). Tourism Management 45: 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudrias, Jean-Sébastien, Patrick Gaudreau, and Heather K. Laschinger. 2004. Testing the structure of psychological empowerment: Does gender make a difference? Educational and Psychological Measurement 64: 861–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, Susmita, Sangita Dutta Gupta, and Parijat Upadhyay. 2018. Empowering women and stimulating development at bottom of pyramid through micro-entrepreneurship. Management Decision 56: 160–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Gilad, Stanley M. Gully, and Dov Eden. 2001. Validation of a new general self-efficacy scale. Organisational Research Methods 4: 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheong, Minyoung, Francis J. Yammarino, Shelley D. Dionne, Seth M. Spain, and Chou-Yu Tsai. 2019. A review of the effectiveness of empowering leadership. The Leadership Quarterly 30: 34–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, Wynne. W. 2010. How to write up and report PLS analyses. Handbook of Partial Least Squares. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/226463554_Handbook_of_Partial_Least_Squares (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Cohen, Jacob. 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, Karen S., Coye Cheshire, Eric Rice, and Sandra Nakagawa. 2013. Social exchange theory. In Handbook of Social Psychology. Dordrecht: Springer, Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/290110057_Social_Exchange_Theory (accessed on 25 December 2021).

- Cropanzano, Russell, and Marie S. Mitchell. 2005. Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management 31: 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dabrowski, Dariusz, Magdalena Brzozowska-Woś, Edyta Gołąb-Andrzejak, and Agnieszka Firgolska. 2019. Market orientation and hotel performance: The mediating effect of creative marketing programs. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 41: 175–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bloom, Jessica, Sabine A.E. Geurts, Toon W. Taris, Sabine Sonnentag, Carolina de Weerth, and Michiel A. J. Kompier. 2010. Effects of vacation from work on health and wellbeing: Lots of fun, quickly gone. Work and Stress 24: 196–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Cremer, David, and Daan Van Knippenberg. 2003. Cooperation with leaders in social dilemmas: On the effects of procedural fairness and outcome favorability in structural cooperation. Organisational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 91: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, Ibrahim, Mohamed Moustafa, Abu Elnasr Sobaih, Meqbel Aliedan, and Alaa M. S. Azazz. 2021. The impact of women’s empowerment on STD: Mediating role of tourism involvement. Tourism Management Perspectives 38: 100815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, Lisa, Tim R.L. Fry, and Leonora Risse. 2016. The significance of financial self-efficacy in explaining women’s personal finance behaviour. Journal of Economic Psychology 54: 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferguson, Lucy, and Daniella Moreno Alarcón. 2016. Gender expertise and the private sector. In The Politics of Feminist Knowledge Transfer. London: Palgrave Macmillan, Available online: https://www.springerprofessional.de/en/gender-expertise-and-the-private-sector/16654818 (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Figueroa-Domecq, Cristina, Anna de Jong, and Allan M. Williams. 2020. Gender, tourism & entrepreneurship: A critical review. Annals of Tourism Research 84: 102980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, Claes, and David F. Larcker. 1981. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research 18: 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, Greg, and Derek Hall. 2000. Tourism and Sustainable Community Development. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gursoy, Dogan, and Erdogan Gavcar. 2003. International leisure tourists’ involvement profile. Annals of Tourism Research 30: 906–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Josep F., G. Thomas. M. Hult, Christian M. Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. 2014. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hair Jr., Joe F., Lucy M. Matthews, Ryan L. Matthews, and Marko Sarstedt. 2017. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. International Journal of Multivariate Data Analysis 1: 107–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., Jeffrey J. Risher, Marko Sarstedt, and Christian M. Ringle. 2019. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review 31: 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, Jörg, Christian M. Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. 2015. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 43: 115–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hersey, Paul, and Kenneth H. Blanchard. 1969. Life cycle theory of leadership. Training & Development Journal 23: 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Huertas-Valdivia, Irene, Araceli Rojo Gallego-Burín, and F. Javier Lloréns-Montes. 2019. Effects of different leadership styles on hospitality workers. Tourism Management 71: 402–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchings, Kate, Char-lee Moyle, Andreas Chai, Nicole Garofano, and Stewart Moore. 2020. Segregation of women in tourism employment in the APEC region. Tourism Management Perspectives 34: 100655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization (ILO). 2017. Sustainable Tourism: A Catalyst for Inclusive Socio-Economic Development and Poverty Reduction in Rural Areas. Geneva: ILO, Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/-groups/public/---ed_dialogue/---sector/documents/publication/wcms_601066.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Iqbal, Adnan, Yahya Melhem, and Husam Kokash. 2012. Readiness of the university students toward entrepreneurship in Saudi private university: An exploratory study. European Scientific Journal 8: 109–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattara, Hanan. 2005. Career challenges for female managers in Egyptian hotels. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 17: 238–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Seong-Seop, David Scott, and John L. Crompton. 1997. An exploration of the relationships among social psychological involvement, behavioral involvement, commitment and future intensions in the context of bird watching. Journal of Leisure Research 29: 320–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutson, Bonnie. J., and Raymond S. Schmidgall. 1999. Dimensions of the glass ceiling in the hospitality industry. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 40: 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, Ned. 2015. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration (IJEC) 11: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krejcie, Robert V., and Daryle W. Morgan. 1970. Determining sample size for research activities. Education Psychological Measurement 30: 607–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusluvan, Salih, and Zeynep Kusluvan. 2000. Perceptions and attitudes of undergraduate tourism students towards working in the tourism industry in Turkey. Tourism Management 21: 251–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, Gerard, Alan Graefe, Robert Manning, and James Bacon. 2003. An examination of the relationship between leisure activity involvement and place attachment among hikers along the Appalachian trail. Journal of Leisure Research 35: 249–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luz, Nimrod. 2020. Pilgrimage and religious tourism in Islam. Annals of Tourism Research 82: 102915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGehee, Nancy G., and Kathleen L. Andereck. 2004. Factors predicting rural residents’ support of tourism. Journal of Travel Research 43: 131–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Hu, Zicheng Ma, Shiwen Jiao, Xiaoyu Chen, Xinyue Lv, and Zehui Zhan. 2017. The sustainable personality in entrepreneurship: The relationship between big six personality, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial intention in the Chinese context. Sustainability 9: 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ministry of Tourism. 2020. Specialized Programs to Raise the Percentage of Saudi Women in the Labor Market to 30%; New Delhi: Ministry of Tourism. Available online: https://mt.gov.sa/MediaCenter/News/GeneralNews/Pages/z-g-3-24-3-2019.aspx (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Mooney, Shelagh, and Irene Ryan. 2009. A woman’s place in hotel management: Upstairs or downstairs? Gender in Management: An International Journal 24: 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mulder Martin, Tanja Weigel, and Kate Collins. 2006. The concept of competence in the development of vocational education and training in selected EU member states: A critical analysis. Journal of Vocational Education and Training 59: 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundfrom, Daniel J., Dale G. Shaw, and Tian Lu Ke. 2005. Minimum sample size recommendations for conducting factor analyses. International Journal of Testing 5: 159–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieva, Florabel Ortega. 2015. Social women entrepreneurship in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research 5: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, Sangwon, and Dae-Young Kim. 2010. A comparison of different approaches to segment information search behavior of spring break travelers in the USA: Experience, knowledge, involvement and specialization concept. International Journal of Tourism Research 12: 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, Linda W., and Irena Ateljevic. 2017. Women empowerment entrepreneurship nexus in tourism: Processes of social innovation. In Tourism and Entrepreneurship. London: Routledge, pp. 94–109. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, Phillip M., and Dennis W. Organ. 1986. Self-reports in organisational research: Problems and prospects. Journal of Management 12: 531–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, Phillip M., Scott B. MacKenzie, and Nathan P. Podsakoff. 2012. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology 63: 539–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prati, Gabriele, and Bruna Zani. 2013. The relationship between psychological empowerment and organisational identification. Journal of Community Psychology 41: 851–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prebensen, Nina K., Eunju Woo, Joseph S. Chen, and Muzaffer Uysal. 2013. Motivation and involvement as antecedents of the perceived value of the destination experience. Journal of Travel Research 52: 253–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prowess. 2021. Inspirational Female Entrepreneurs from History. Available online: https://www.prowess.org.uk/inspirational-female-entrepreneurs-from-history/ (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Russen, Michelle, Mary Dawson, and Juan M. Madera. 2021. Gender diversity in hospitality and tourism top management teams: A systematic review of the last 10 years. International Journal of Hospitality Management 95: 102942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saudi Gazette. 2021. 54% of Workers in Tourism Are Women: Saudi Minister. Available online: https://www.zawya.com/mena/en/business/story/54_of_workers_in_tourism_are_women_Saudi_minister-SNG_255437175/ (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Scheepers, Daan, and Naomi Ellemers. 2019. Social identity theory. Social Psychology in Action. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334158426_Social_Identity_Theory (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- Scheyvens, Regina. 2000. Promoting women’s empowerment through involvement in ecotourism: Experiences from the Third World. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 8: 232–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slåtten, Terje, and Mehmet Mehmetoglu. 2011. What are the drivers for innovative behavior in frontline jobs? A study of the hospitality industry in Norway. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism 10: 254–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Issac H., and Warner P. Woodworth. 2012. Developing social entrepreneurs and social innovators: A social identity and self-efficacy approach. Academy of Management Learning & Education 11: 390–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, Daniel, Valentina Vasile, Anca Oltean, Calin-Adrian Comes, Anamari-Beatrice Stefan, Liviu Ciucan-Rusu, Elena Bunduchi, Maria-Alexandra Popa, and Mihai Timus. 2021. Women Entrepreneurship and Sustainable Business Development: Key Findings from a SWOT—AHP Analysis. Sustainability 13: 5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, Mervyn. 1974. Cross-validatory choice and assessment of statistical predictions. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological) 36: 111–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartanto, Dwi, David Dean, Ruhadi Nansuri, and N. N. Triyuni. 2018. The link between tourism involvement and service performance: Evidence from frontline retail employees. Journal of Business Research 83: 130–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsung, Hung L. 2013. Influence analysis of community resident support for STD. Tourism Management 34: 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). 2013. Sustainable Tourism for Development Guidebook: Enhancing Capacities for Sustainable Tourism for Development in Developing Countries. Madrid: UNWTO. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valek, Natasa Slak, and Hamed Almuhrzi. 2021. Women in Tourism in Asian Muslim Countries. Available online: https://www.amazon.com/Women-Tourism-Muslim-Countries-Perspectives/dp/9813347562 (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Valeri, Marco, and Vicky Katsoni. 2021. Female entrepreneurship in tourism. In Gender and Tourism. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited, pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhees, Frans J. H. M., and Matthew T. G. Meulenberg. 2004. Market orientation, innovativeness, product-innovation and performance in small firms. Journal of Small Business Management 42:: 134–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vossenberg, Saskia. 2013. Women Entrepreneurship Promotion in Developing Countries: What Explains the Gender Gap in Entrepreneurship and How to Close It. Maastricht School of Management Working Paper Series; Maastricht: Maastricht School of Management, pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- World Tourism Organisation. 2022. Global Report on Women in Tourism. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284420384 (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC). 2017. Sustainability Reporting in Travel & Tourism. Available online: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-developmentgoals/ (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Wu, Lingfei, and Jun Li. 2011. Perceived value of entrepreneurship: A study of the cognitive process of entrepreneurial career decision. Journal of Chinese Entrepreneurship 3: 134–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoopetch, Chanin. 2020. Women empowerment, attitude toward risk-taking and entrepreneurial intention in the hospitality industry. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research 15: 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Description | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 21 to 30 | 51 | 25.3% |

| 31 to 40 | 79 | 39.4% | |

| 41 and above | 71 | 35.3% | |

| Years in business | 0 to 5 | 106 | 52.7% |

| 5 to 10 | 72 | 35.8% | |

| 10 and above | 23 | 11.5% | |

| Type of business | Accommodation business | 41 | 20.4% |

| Restaurants | 97 | 39.3% | |

| Travel and recreation | 63 | 31.3% | |

| Location of business | Riyadh | 69 | 34.32% |

| Madinah | 44 | 21.89% | |

| Taif | 26 | 12.93% | |

| Jeddah | 32 | 15.92% | |

| Dammam | 30 | 14.94% |

| Constructs | Items | Factor Loading | AVE | CR | α | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perception of Women’s Work | PWW1 | 0.884 | 0.717 | 0.926 | 0.9 | 2.065 |

| PWW2 | 0.709 | |||||

| PWW3 | 0.856 | |||||

| PWW4 | 0.87 | |||||

| PWW5 | 0.899 | |||||

| Self-efficacy | SE1 | 0.787 | 0.663 | 0.881 | 0.839 | 1.496 |

| SE2 | 0.8 | |||||

| SE4 | 0.756 | |||||

| SE5 | 0.726 | |||||

| SE6 | 0.713 | |||||

| SE7 | 0.671 | |||||

| Empowering Leadership | EL1 | 0.862 | 0.79 | 0.719 | 0.867 | 2.082 |

| EL2 | 0.92 | |||||

| EL3 | 0.885 | |||||

| Psychological Empowerment | PE1 | 0.753 | 0.699 | 0.902 | 0.865 | 1.068 |

| PE2 | 0.845 | |||||

| PE3 | 0.812 | |||||

| PE4 | 0.926 | |||||

| Tourism Involvement | TI1 | 0.808 | 0.675 | 0.871 | 0.828 | 1.002 |

| TI2 | 0.787 | |||||

| TI3 | 0.717 | |||||

| TI4 | 0.743 | |||||

| TI5 | 0.734 | |||||

| Sustainable Tourism Development | STD1 | 0.915 | 0.83 | 0.936 | 0.897 | 2.021 |

| STD2 | 0.928 | |||||

| STD3 | 0.89 |

| Variables | STD | EL | PWW | PE | SE | TI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainable Tourism Development | ||||||

| Empowering Leadership | 0.817 | |||||

| Perception of Women’s Work | 0.808 | 0.806 | ||||

| Psychological Empowerment | 0.679 | 0.464 | 0.401 | |||

| Self-efficacy | 0.552 | 0.568 | 0.588 | 0.341 | ||

| Tourism Involvement | 0.701 | 0.710 | 0.804 | 0.283 | 0.587 |

| Variables | Mean | SD | PWW | SE | EL | PE | TI | STD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PWW | 3.837 | 0.907 | 1.00 | |||||

| SE | 3.824 | 0.836 | 0.510 ** | 1.00 | ||||

| EL | 4.022 | 0.895 | 0.710 ** | 0.486 ** | 1.00 | |||

| PE | 3.856 | 0.923 | 0.058 * | 0.380 ** | 0.143 * | 1.00 | ||

| TI | 4.101 | 0.692 | 0.756 ** | 0.502 ** | 0.614 ** | 0.154 ** | 1.00 | |

| STD | 4.024 | 0.926 | 0.725 ** | 0.481 ** | 0.370 ** | 0.160 ** | 0.619 ** | 1.00 |

| Paths | β Value | SE | T-Values | BCI LL | BCI UL | f2 | p-Values | Decision | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | PWW ≥ TI | 0.636 | 0.068 | 9.322 | 0.487 | 0.718 | 0.548 | 0.000 *** | Supported |

| H2 | SE ≥ TI | 0.140 | 0.059 | 2.389 | 0.012 | 0.208 | 0.037 | 0.027 *** | Supported |

| H3 | EL ≥ TI | 0.112 | 0.053 | 2.122 | −0.007 | 0.196 | 0.023 | 0.047 ** | Supported |

| H4 | PE ≥ TI | 0.300 | 0.051 | 3.067 | 0.009 | 0.184 | 0.214 | 0.007 *** | Supported |

| H5 | TI ≥ STD | 0.624 | 0.039 | 15.886 | 0.551 | 0.685 | 0.637 | 0.000 *** | Supported |

| SSO | SSE | Q2 = (1-SSE/SSO) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tourism involvement | 861.000 | 588.527 | 0.316 |

| Sustainable tourism development | 1435.000 | 969.428 | 0.324 |

| R-square | |||

| Tourism involvement | 0.643 | ||

| Sustainable tourism development | 0.389 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Samad, S.; Alharthi, A. Untangling Factors Influencing Women Entrepreneurs’ Involvement in Tourism and Its Impact on Sustainable Tourism Development. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12020052

Samad S, Alharthi A. Untangling Factors Influencing Women Entrepreneurs’ Involvement in Tourism and Its Impact on Sustainable Tourism Development. Administrative Sciences. 2022; 12(2):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12020052

Chicago/Turabian StyleSamad, Sarminah, and Alaa Alharthi. 2022. "Untangling Factors Influencing Women Entrepreneurs’ Involvement in Tourism and Its Impact on Sustainable Tourism Development" Administrative Sciences 12, no. 2: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12020052

APA StyleSamad, S., & Alharthi, A. (2022). Untangling Factors Influencing Women Entrepreneurs’ Involvement in Tourism and Its Impact on Sustainable Tourism Development. Administrative Sciences, 12(2), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12020052