The Pitch: Some Face-to-Face Minutes to Build Trust

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Entrepreneur–Investor Configuration

2.1. Main Entrepreneur–Investor Configurations

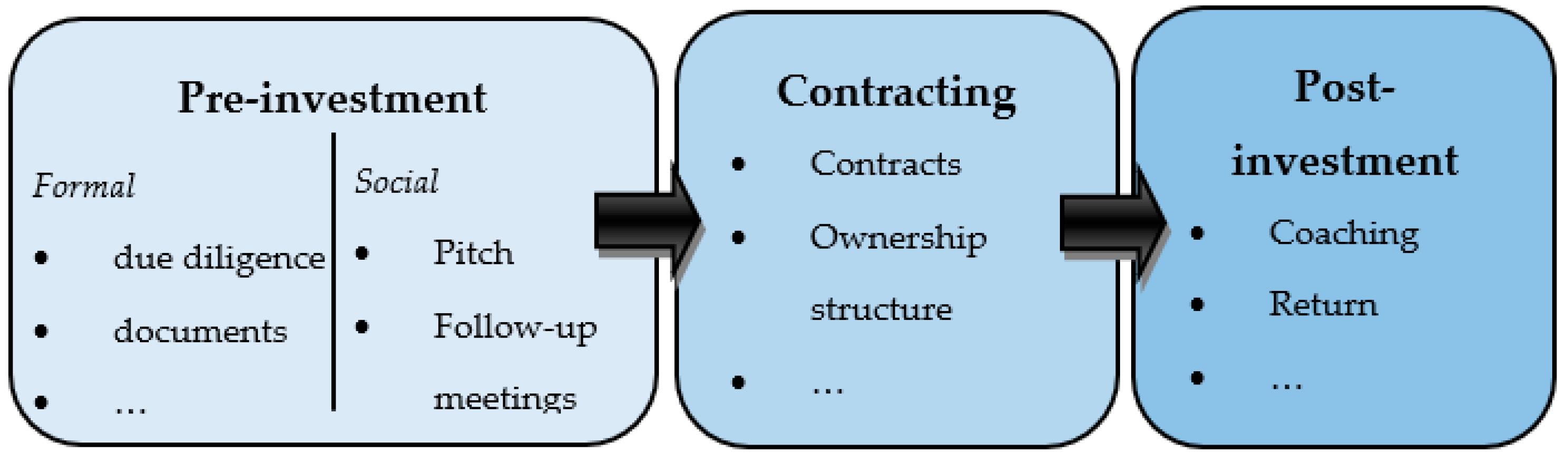

2.2. Decision in a Single-Investor–Single-Entrepreneur Configuration

3. Trust

3.1. Theoretical Approach of Trust Development

- Bestowed trust. This kind of trust appears when several investors compete and decide to focus on choices that create trust. These behaviors aim to increase the value creation and improve the feeling of fairness and the density of relationships (Nooteboom 2002).

- Dyadic trust. This form of trust can be understood as trust under the condition of reciprocity. Behaviors are focused on increasing joint outcomes (Baer et al. 2015; Kong et al. 2014).

- Knowledge-based trust. Implying that a party as trustable based on the diploma or experience of the other (Lewicki et al. 2006).

- Identification-based trust. This theory supposed that trust is based on inclusion in a specific community. Shared culture and values is the foundation of trust (Baer et al. 2018).

3.2. Trust Raising and Trust Damaging Behaviours

3.3. Elements of Trust during Swift Cooperation

4. The Pitch Moment

4.1. The Documentation and Formal Aspects before the Pitch Moment

4.2. The Pitch, the Socializing Moment

4.3. Validation of the Best Partner, Traits and Characteristics

- The Entrepreneur’s Characteristics

- Investors’ Characteristics

5. Conclusions

5.1. Propositions

5.2. Limitations and Further Research Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ambady, Nalini, Frank J. Bernieri, and Jennifer A. Richeson. 2000. Toward a Histology of Social Behavior: Judgmental Accuracy from Thin Slices of the Behavioral Stream. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Cambridge: Academic Press, vol. 32, pp. 201–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anokhin, Sergey, Joakim Wincent, and Pejvak Oghazi. 2016. Strategic Effects of Corporate Venture Capital Investments. Journal of Business Venturing Insights 5: 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Applegate, Lynda, and Carole Carlson. 2014. Entrepreneurship Reading: Developing Business Plans and Pitching Opportunities. Harvard Business Publishing 8062. [Google Scholar]

- Baer, Michael D., Rashpal K. Dhensa-Kahlon, Jason A. Colquitt, Jessica B. Rodell, Ryan Outlaw, and David M. Long. 2015. Uneasy Lies the Head That Bears the Trust: The Effects of Feeling Trusted on Emotional Exhaustion. Academy of Management Journal 58: 1637–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baer, Michael D., Fadel K. Matta, Ji Koung Kim, David T. Welsh, and Niharika Garud. 2018. It’s Not You, It’s Them: Social Influences on Trust Propensity and Trust Dynamics. Personnel Psychology 71: 423–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balachandra, Lakshmi. 2017. How Venture Capitalists Really Assess a Pitch. Harvard Business Review 95: 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Balachandra, Lakshmi, Harry Sapienza, and Dennie Kim. 2014. How Critical Cues Influence Angels’ Investment Preferences. Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research 34: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bammens, Yannick, and Veroniek Collewaert. 2014. Trust Between Entrepreneurs and Angel Investors: Exploring Positive and Negative Implications for Venture Performance Assessments. Journal of Management 40: 1980–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessière, Véronique, Eric Stéphany, and Peter Wirtz. 2020. Crowdfunding, Business Angels, and Venture Capital: An Exploratory Study of the Concept of the Funding Trajectory. Venture Capital 22: 135–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, Steve. 2013. Why the Lean Start-Up Changes Everything. Harvard Business Review 91: 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Bubna, Amit, Sanjiv R. Das, and Nagpurnanand Prabhala. 2020. Venture Capital Communities. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 55: 621–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger-Helmchen, Thierry. 2007. Rules of Thumb and Real Option Decision Biases for Optimally Imperfect Decisions: A Simulation-Based Exploration. Investment Management and Financial Innovations 4: 105–18. [Google Scholar]

- Burger-Helmchen, Thierry, Blandine Laperche, Francesco Schiavone, and Ulrike Stefani. 2020. Financing Novelty: New Tools and Practices to Induce and Control Innovation Processes. European Journal of Innovation Management 23: 197–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, Andrew, Stuart Fraser, and Francis J. Greene. 2010. The Multiple Effects of Business Planning on New Venture Performance. Journal of Management Studies 47: 391–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cable, Daniel M., and Scott Shane. 1997. A Prisoner’s Dilemma Approach to Entrepreneur-Venture Capitalist Relationships. The Academy of Management Review 22: 142–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagna, Rachel L., Kurt T. Dirks, Andrew P. Knight, Craig Crossley, and Sandra L. Robinson. 2020. On the Relation between Felt Trust and Actual Trust: Examining Pathways to and Implications of Leader Trust Meta-Accuracy. The Journal of Applied Psychology 105: 994–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, Jean S., Joep P. Cornelissen, and Mark P. Healey. 2018. Actions Speak Louder than Words: How Figurative Language and Gesturing in Entrepreneurial Pitches Influences Investment Judgments. Academy of Management Journal 62: 335–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daly, Peter, and Dennis Davy. 2016. Structural, Linguistic and Rhetorical Features of the Entrepreneurial Pitch. Journal of Management Development 35: 120–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drover, Will, Lowell Busenitz, Sharon Matusik, David Townsend, Aaron Anglin, and Gary Dushnitsky. 2017. A Review and Road Map of Entrepreneurial Equity Financing Research: Venture Capital, Corporate Venture Capital, Angel Investment, Crowdfunding, and Accelerators. Journal of Management 43: 1820–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ewens, Michael, and Matt Marx. 2018. Founder Replacement and Startup Performance. The Review of Financial Studies 31: 1532–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Vázquez, José-Santiago, and Roberto-Carlos Álvarez-Delgado. 2020. Persuasive Strategies in the SME Entrepreneurial Pitch: Functional and Discursive Considerations. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istrazivanja 33: 2342–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Flynn, David M. 1991. The Critical Relationship between Venture Capitalists and Entrepreneurs: Planning, Decision-Making, and Control. Small Business Economics 3: 185–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georget, Valentine, and Thierry Rayna. 2021. Sortie de l’intrapreneuriat: Une réflexion sur les trajectoires professionnelles subjectives. Innovations 65: 247–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godlewski, Christophe, Bulat Sanditov, and Thierry Burger-Helmchen. 2012. Bank Lending Networks, Experience, Reputation, and Borrowing Costs: Empirical Evidence from the French Syndicated Lending Market. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting 39: 113–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gompers, Paul A., Will Gornall, Steven N. Kaplan, and Ilya A. Strebulaev. 2020. How Do Venture Capitalists Make Decisions? Journal of Financial Economics 135: 169–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graebner, Melissa E. 2009. Caveat Venditor: Trust Asymmetries in Acquisitions of Entrepreneurial Firms. The Academy of Management Journal 52: 435–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greene, Francis J., and Christian Hopp. 2018. Research: Writing a Business Plan Makes Your Start-up More Likely to Succeed. Harvard Business Review, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hallen, Benjamin L., and Emily Cox Pahnke. 2016. When Do Entrepreneurs Accurately Evaluate Venture Capital Firms’ Track Records? A Bounded Rationality Perspective. Academy of Management Journal 59: 1535–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, Richard T., Mark R. Dibben, and Colin M. Mason. 1997. The Role of Trust in the Informal Investor’s Investment Decision: An Exploratory Analysis. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 21: 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongtao, Yang, and Li Haiyan. 2018. Trust Cognition of Entrepreneurs’ Behavioral Consistency Modulates Investment Decisions of Venture Capitalists in Cooperation. Entrepreneurship Research Journal 8: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, Teck-Hua, and Keith Weigelt. 2005. Trust Building Among Strangers. Management Science 51: 519–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, Laura, and Jone L. Pearce. 2015. Managing the Unknowable: The Effectiveness of Early-Stage Investor Gut Feel in Entrepreneurial Investment Decisions. Administrative Science Quarterly 60: 634–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaiser, Manuel, and Elisabeth S. C. Berger. 2021. Trust in the Investor Relationship Marketing of Startups: A Systematic Literature Review and Research Agenda. Management Review Quarterly 71: 491–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, Steven N., Berk Sensoy, and Per Strömberg. 2009. Should Investors Bet on the Jockey or the Horse? Evidence from the Evolution of Firms from Early Business Plans to Public Companies. The Journal of Finance 64: 75–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohtamäki, Marko, Tauno Kekäle, and Riitta Viitala. 2004. Trust and Innovation: From Spin-Off Idea to Stock Exchange. Creativity and Innovation Management 13: 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Dejun Tony, Kurt T. Dirks, and Donald L. Ferrin. 2014. Interpersonal Trust within Negotiations: Meta-Analytic Evidence, Critical Contingencies, and Directions for Future Research. Academy of Management Journal 57: 1235–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leimsider, Rich, and Cheryl Dorsey. 2013. Entrepreneurs: You’re More Important Than Your Business Plan. Harvard Business Review 18: 2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Lewicki, Roy J., Edward C. Tomlinson, and Nicole Gillespie. 2006. Models of Interpersonal Trust Development: Theoretical Approaches, Empirical Evidence, and Future Directions. Journal of Management 32: 991–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macmillan, Ian C., Robin Siegel, and P. N. Subba Narasimha. 1985. Criteria Used by Venture Capitalists to Evaluate New Venture Proposals. Journal of Business Venturing 1: 119–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, Andrew L., and Moren Lévesque. 2014. Trustworthiness: A Critical Ingredient for Entrepreneurs Seeking Investors. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 38: 1057–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, Rita Gunther. 1999. Falling Forward: Real Options Reasoning and Entrepreneurial Failure. Academy of Management Review 24: 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muller, Emmanuel, Andrea Zenker, and Jean-Alain Héraud. 2015. Knowledge Angels: Creative Individuals Fostering Innovation in KIBS. Observations from Canada, China, France, Germany and Spain. Management International 19: 201–18. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson, Nigel, Pino G. Audia, and Madan Pillutla. 2006. Organizational Behavior. In The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Management. Hoboken: Blackwell Publishers, vol. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Nooteboom, Bart. 2002. Trust: Forms, Foundations, Functions & Failures. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Pahnke, Emily Cox, Riitta Katila, and Kathleen M. Eisenhardt. 2015. Who Takes You to the Dance? How Partners’ Institutional Logics Influence Innovation in Young Firms. Administrative Science Quarterly 60: 596–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pentland, Brian T., and Henry H. Rueter. 1994. Organizational Routines as Grammars of Action. Administrative Science Quarterly 39: 484–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, Lawrence A., Thomas H. Allison, and Brian L. Connelly. 2016. Better Together? Signaling Interactions in New Venture Pursuit of Initial External Capital. Academy of Management Journal 59: 1585–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, Jeffrey M., Matthew W. Rutherford, and Brian G. Nagy. 2012. Preparedness and Cognitive Legitimacy as Antecedents of New Venture Funding in Televised Business Pitches. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 36: 915–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, John E., and Igor Filatotchev. 2021. The Business Model Phenomenon: Towards Theoretical Relevance. Journal of Management Studies 58: 517–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, Michael, and Lauren Barley. 2014. How Venture Capitalists Evaluate Potential Venture Opportunities. Harvard Business School Case, 805–019. [Google Scholar]

- Salamon, Sabrina Deutsch, and Sandra L. Robinson. 2008. Trust That Binds: The Impact of Collective Felt Trust on Organizational Performance. Journal of Applied Psychology 93: 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefani, Ulrike, Francesco Schiavone, Blandine Laperche, and Thierry Burger-Helmchen. 2019. New Tools and Practices for Financing Novelty: A Research Agenda. European Journal of Innovation Management 23: 314–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, Edward C., Brian R. Dineen, and Roy J. Lewicki. 2009. Trust Congruence among Integrative Negotiators as a Predictor of Joint-behavioral Outcomes. International Journal of Conflict Management 20: 173–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tuggle, Christopher, Karen Schnatterly, and Richard Johnson. 2010. Attention Patterns in the Boardroom: How Board Composition and Processes Affect Discussion of Entrepreneurial Issues. The Academy of Management Journal 53: 550–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallmeroth, Johannes, Peter Wirtz, Alexander Groh, and Alexander Peter. 2018. Venture Capital, Angel Financing, and Crowdfunding of Entrepreneurial Ventures: A Literature Review. Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship 14: 1–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Daojuan, and Thomas Schøtt. 2022. Coupling between Financing and Innovation in a Startup: Embedded in Networks with Investors and Researchers. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 18: 327–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werven, Ruben van, Onno Bouwmeester, and Joep P. Cornelissen. 2019. Pitching a Business Idea to Investors: How New Venture Founders Use Micro-Level Rhetoric to Achieve Narrative Plausibility and Resonance. International Small Business Journal 37: 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wheatcroft, John. 2016. Entrepreneurs Need to Be Pitch Perfect. Human Resource Management International Digest 24: 26–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, Brett Anthony, and John Dumay. 2020. The Angel Investment Decision: Insights from Australian Business Angels. Accounting & Finance 60: 3133–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Forrest. 2017. How Do Entrepreneurs Obtain Financing? An Evaluation of Available Options and How They Fit into the Current Entrepreneurial Ecosystem. Journal of Business & Finance Librarianship 22: 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Multiple Investors | Single INVESTOR | |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple projects | Bessière et al. (2020) Drover et al. (2017) Wallmeroth et al. (2018) White and Dumay (2020) | Anokhin et al. (2016) Flynn (1991) Gompers et al. (2020) Graebner (2009) Macmillan et al. (1985) |

| Single Project | Bubna et al. (2020) Bessière et al. (2020) Drover et al. (2017) Godlewski et al. (2012) Wallmeroth et al. (2018) Wright (2017) | Burger-Helmchen et al. (2020) Hallen and Pahnke (2016) Kaplan et al. (2009) Roberts and Barley (2014) White and Dumay (2020) Wright (2017) |

| Key Question | Behavioural | Psychological/Transformational |

|---|---|---|

| How is trust defined and measured? | Defined in terms of choice behaviour, which is derived from confidence and expectations; assumes rational choices. Measured by cooperative behaviours | Defined in terms of the basis of trust (expected costs and benefits, knowledge of the other, degree of shared values and identity). Measured by scale items where trust is rated along different qualitative indicators of different stages. |

| At what level does trust begin? | Trust begins at zero when no prior information is available. Trust initiated by cooperative acts by the other, or indication of their motivational orientation. | Trust begins at a calculative based stage. Trust initiated by reputation, structures that provide rewards for trustworthiness and deterrents for defection. |

| What causes the level of trust (distrust) to change over time? | Trust grows as cooperation is extended or reciprocated. Trust declines when the other does not reciprocate cooperation. | Trust grows as cooperation is extended or reciprocated. Trust declines when the other does not reciprocate cooperation. |

| Behavioural Trust Dimensions | Manifestation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Build Trust | Damage Trust | Violate Trust | ||

| Trustworthy | Consistency | Displays of behaviour that confirm promises | Shows inconsistencies between words and actions | Fails to keep promises and agreements |

| Benevolence | Exhibits concern about the well-being of others | Shows self-interest ahead of others’ well-being | Takes advantage of others when they are vulnerable | |

| Alignment | Actions confirm shared values and/or objectives | Behaviours are sometimes inconsistent with declared values | Takes advantage of others when they are vulnerable | |

| Capable | Competence | Displays relevant technical and/or business ability | Shows a lack of context-specific ability | Misrepresents ability |

| Experience | Demonstrates relevant work and/or training experience | Relies on inappropriate experience to make decisions | Misrepresents experience | |

| Judgment | Confirms ability to make accurate and objective decisions | Relies inappropriately on third parties | Judges others without explanation | |

| Trusting | Disclosure | Shares confidential information | Shares confidential information without thinking of consequences | Shares confidential information likely to cause damage |

| Reliance | Shows willingness to be vulnerable through delegation of tasks | Reluctant to delegate, or introduces controls on subordinates’ performances | Does not delegate, or blames subordinates for all errors | |

| Receptiveness | Demonstrates “coachability” and a willingness to change | Reluctant to follow advice | Refutes advice even in the face of evidence | |

| Communicative | Accuracy | Provides truthful and timely information | Unintentionally misrepresents or delays information transmission | Deliberately misrepresents or conceals critical information |

| Explanation | Explains details and consequence of information provided | Ignores request for explanations | Dismisses request for explanations | |

| Openness | Open to new ideas or new ways of doing things | Does not listen or refutes feedback | Shuts down or undermines new ideas | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guimtrandy, F.; Burger-Helmchen, T. The Pitch: Some Face-to-Face Minutes to Build Trust. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12020047

Guimtrandy F, Burger-Helmchen T. The Pitch: Some Face-to-Face Minutes to Build Trust. Administrative Sciences. 2022; 12(2):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12020047

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuimtrandy, Fabien, and Thierry Burger-Helmchen. 2022. "The Pitch: Some Face-to-Face Minutes to Build Trust" Administrative Sciences 12, no. 2: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12020047

APA StyleGuimtrandy, F., & Burger-Helmchen, T. (2022). The Pitch: Some Face-to-Face Minutes to Build Trust. Administrative Sciences, 12(2), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12020047