A Triad of Uppsala Internationalization of Emerging Markets Firms and Challenges: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

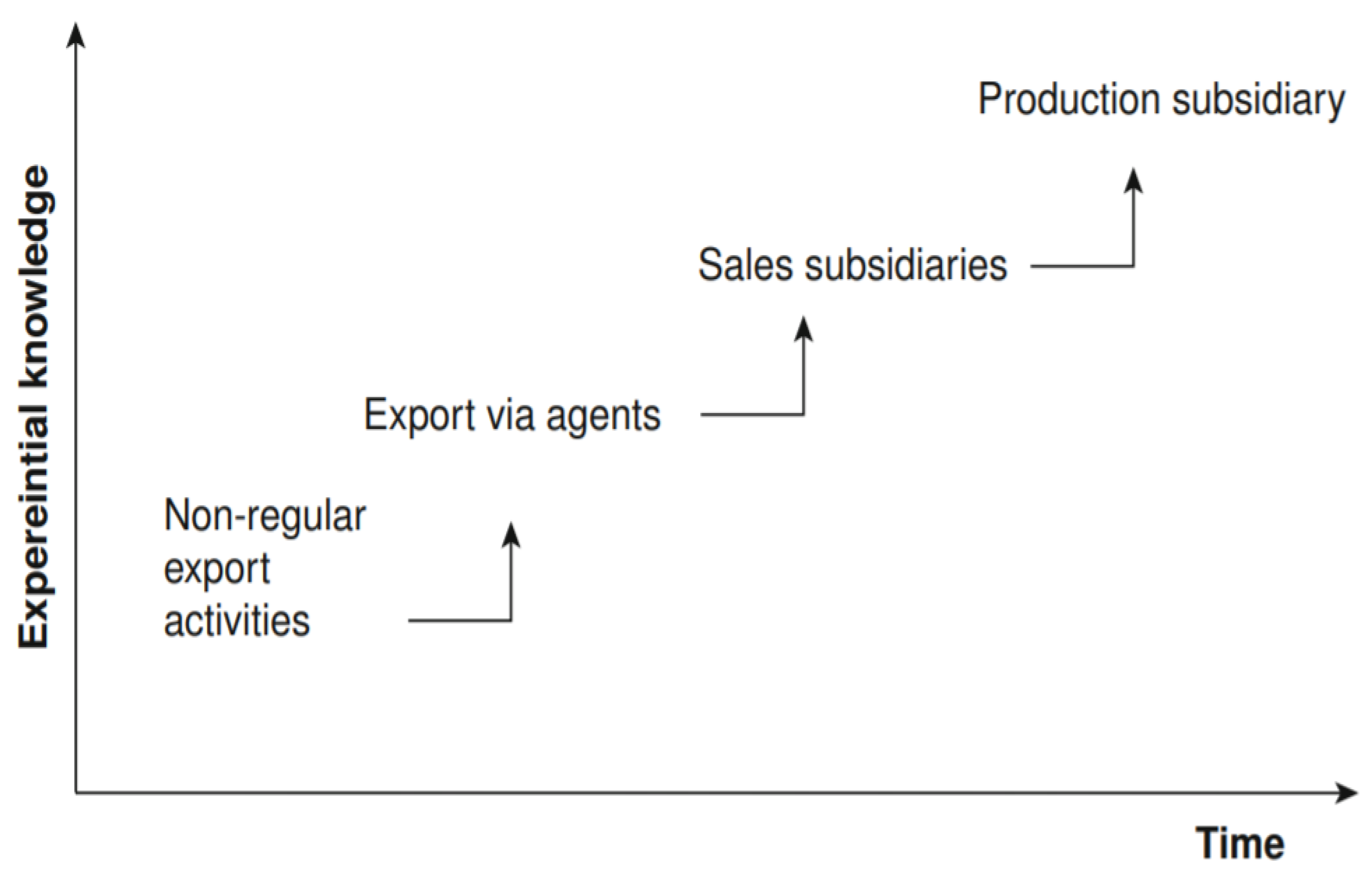

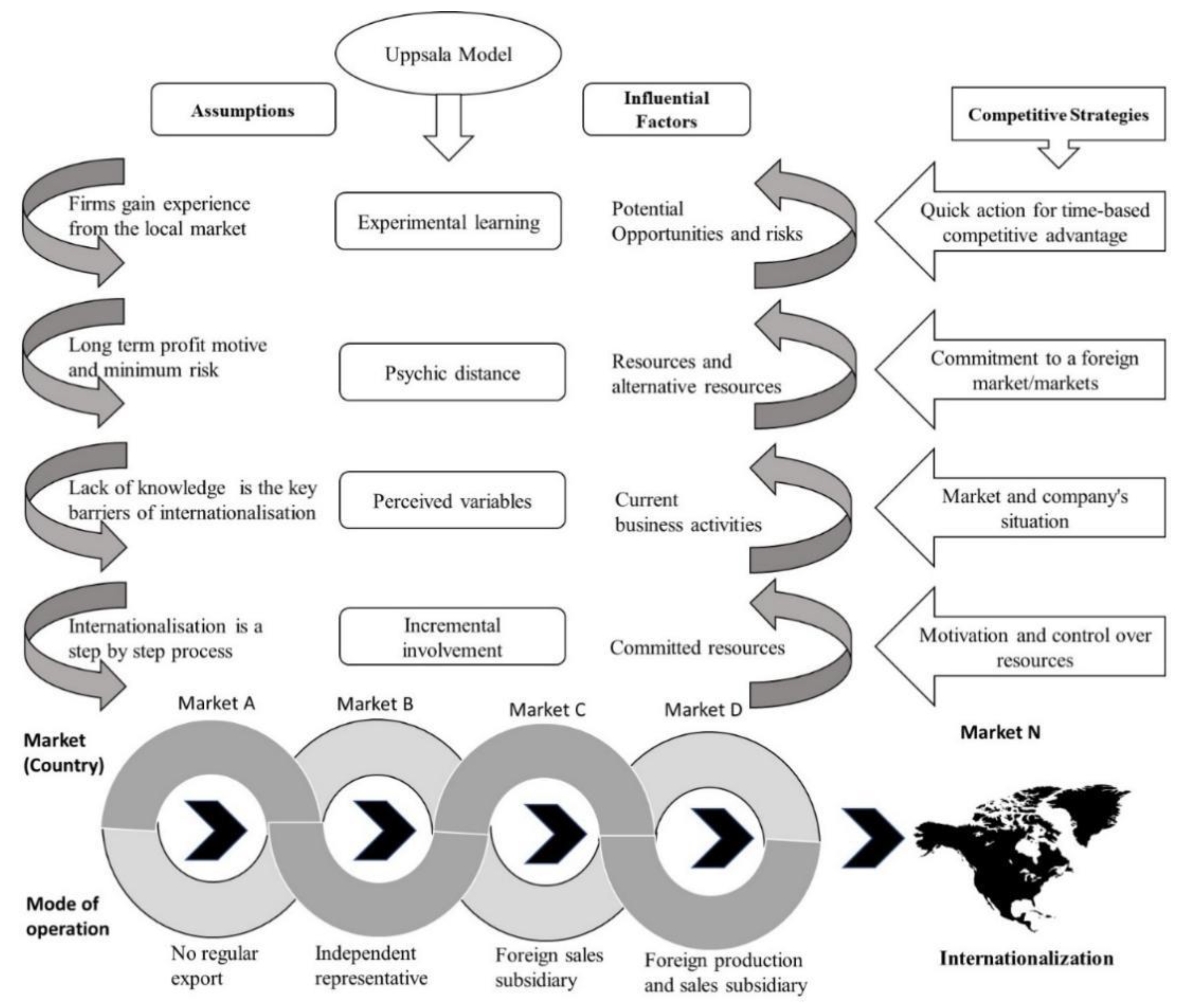

2. Theoretical Background—Uppsala Model

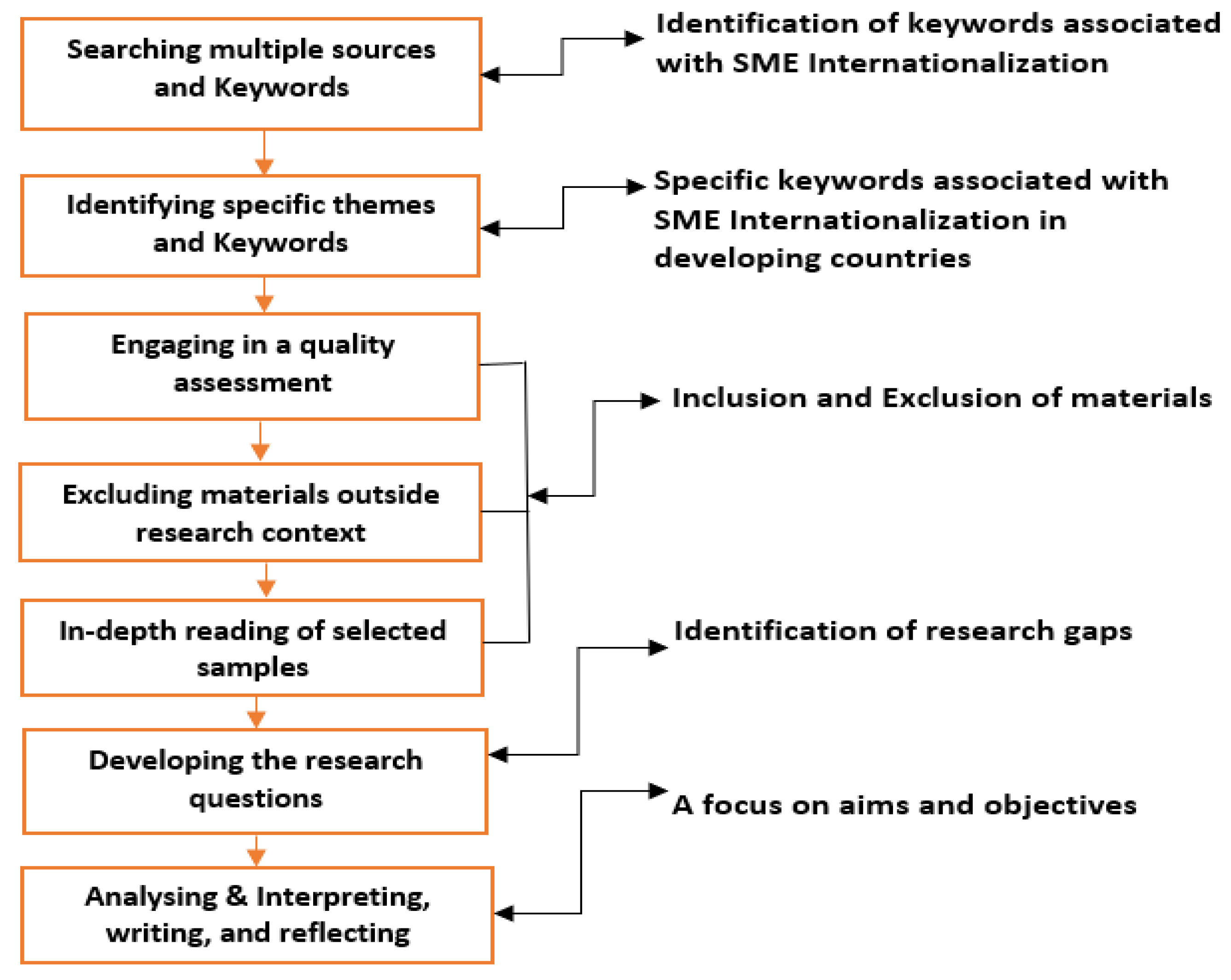

3. Method

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

3.3. Initial Search Keywords

3.4. Quality Assessment

4. Results and Findings

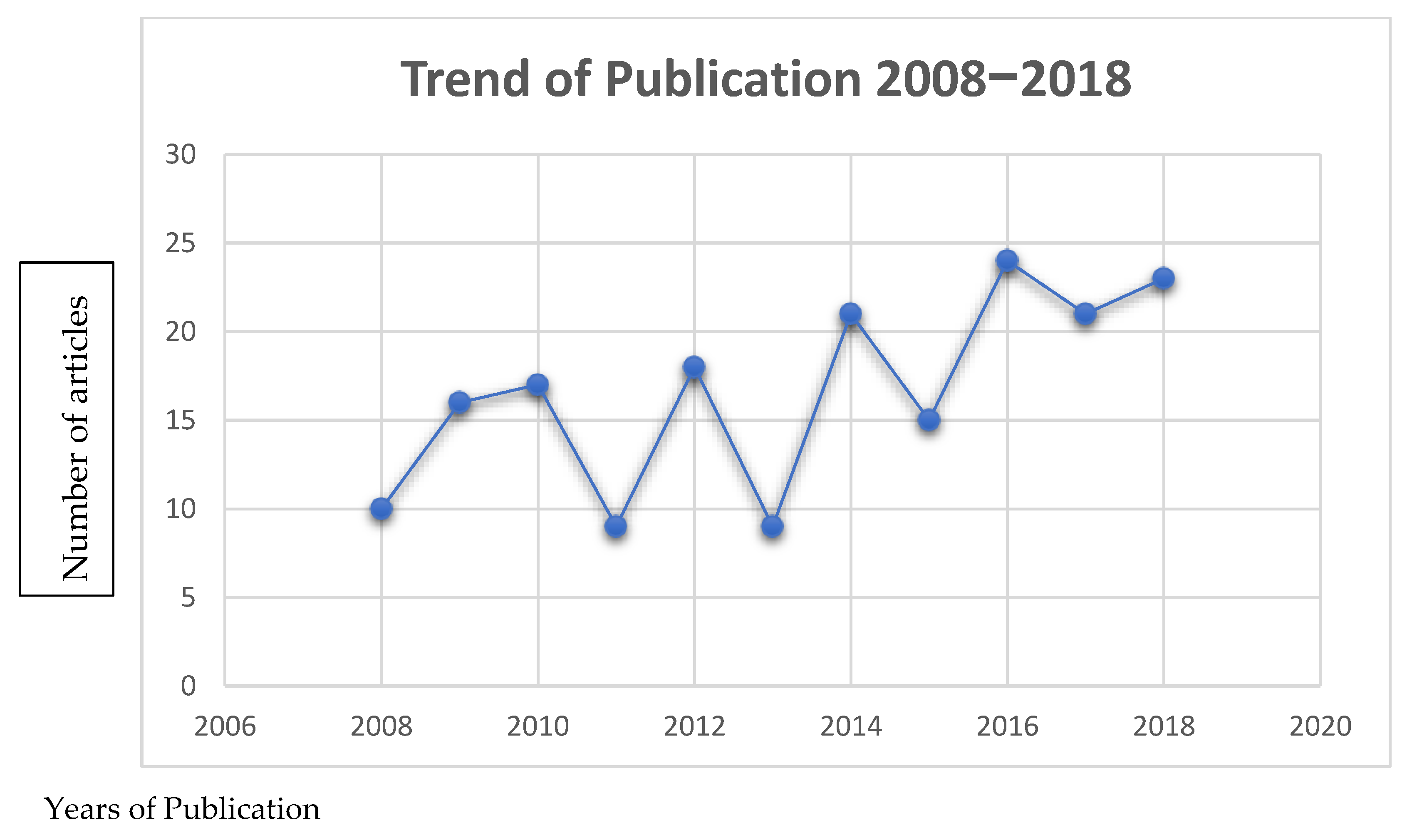

4.1. Systematic Review Data

4.2. Systematic Review Results

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Integrated Uppsala Model of Early and Speed of Internationalization

5.2. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdi, Majid, and Preet S. Aulakh. 2018. Internationalisation and performance: Degree, duration, and scale of operations. Journal of International Business Studies 49: 832–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acs, Zoltan J., and Siri Terjesen. 2013. Born local: Toward a theory of new venture’s choice of internationalization. Small Business Economics 41: 521–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegbile, Abiodun, and David Sarpong. 2018. Disruptive innovation at the base-of-the-pyramid: Opportunities, and challenges for multinationals in African emerging markets. Critical Perspectives on International Business 14: 111–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Syed Zamberi. 2014. Small and medium enterprises’ internationalisation and business strategy: Some evidence from firms located in an emerging market. Journal of Asia Business Studies 8: 168–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemayehu, Binyam Zewde, and Jurie Van Vuuren. 2017. Munificence contingent small business growth model (special emphasis to African SMEs’ context). Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship 29: 251–69. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hyari, K., Ghazi Al-Weshah, and Muhammed Alnsour. 2012. Barriers to internationalisation in SMEs: Evidence from Jordan. Marketing Intelligence & Planning 30: 188–211. [Google Scholar]

- Amal, Mohamed, and Freitag Filho Alexandre Rocha. 2010. Internationalization of small- and medium-sized enterprises: A multi case study. European Business Review 22: 608–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amankwah-Amoah, Joseph, Nathaniel Boso, and Yaw A. Debrah. 2018. Africa rising in an emerging world: An international marketing perspective. International Marketing Review 35: 550–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambos, Tina C., Bodo B. Schlegelmilch, Bjorn Ambos, and Barbara Brenner. 2009. Evolution of Organisational Structure and Capabilities in Internationalising Banks: The CEE Operations of UniCredit’s Vienna Office. Long Range Planning 42: 633–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amdam, Rolv Petter. 2009. The internationalization process theory and the internationalization of Norwegian firms, 1945 to 1980. Business History 51: 445–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoako, Isaac Oduro, and Harry Matlay. 2015. Norms and trust-shaping relationships among food-exporting SMEs in Ghana. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation 16: 123–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, Poul Houman, Poul Rind Christensen, and Torben Damgaard. 2009. Diverging expectations in buyer–seller relationships: Institutional contexts and relationship norms. Industrial Marketing Management 38: 814–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Wineaster. 2011. Internationalization Opportunities and Challenges for Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises from Developing Countries. Journal of African Business 12: 198–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anning-Dorson, Thomas. 2018. Innovation and competitive advantage creation: The role of organisational leadership in service firms from emerging markets. International Marketing Review 35: 580–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annushkina, Olga E., and Renata Trinca Colonel. 2013. Foreign market selection by Russian MNEs—Beyond a binary approach? Critical Perspectives on International Business 9: 58–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, Syed Tariq. 2017. Alibaba: Entrepreneurial growth and global expansion in B2B/B2C markets. Journal of International Entrepreneurship 15: 366–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athreye, Suma, Asli Tuncay-Celikel, and Vandana Ujjual. 2014. Internationalisation of R&D into Emerging Markets: Fiat’s R&D in Brazil, Turkey and India. Long Range Planning 47: 100–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Wensong, Christine Holmström-Lind, and Martin Johanson. 2018. Leveraging networks, capabilities and opportunities for international success: A study on returnee entrepreneurial ventures. Scandinavian Journal of Management 34: 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarek, Rebecca, and Paula Jarzabkowski. 2018. Toward a social practice theory of relational competing. Strategic Management Journal 39: 794–829. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Ron, and Ram Herstein. 2015. Strategies for marketing diamonds in China from the perspective of international diamond SMEs compared to the west. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 22: 549–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berko, Obi Obeng Damoah. 2018. A critical incident analysis of the export behaviour of SMEs: Evidence from an emerging market. Critical Perspectives on International Business 14: 309–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, Arindam K., and David C. Michael. 2008. How local companies keep multinationals at bay. Harvard Business Review 86: 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bhaumik, Sumon Kumar, Nigel Driffield, and Sarmistha Pal. 2010. Does ownership structure of emerging-market firms affect their outward FDI? The case of the Indian automotive and pharmaceutical sectors. Journal of International Business Studies 41: 437–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggam, J. 2015. Succeeding with Your Master’s Dissertation: A Step-By-Step Handbook, 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Boehe, Dirk Michael, Gongming Qian, and Mike W. Peng. 2016. Export intensity, scope, and destinations: Evidence from Brazil. Industrial Marketing Management 57: 127–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boso, Nathaniel, Ifedapo Adeleye, Kevin Ibeh, and Amon Chizema. 2018. The internationalization of African firms: Opportunities, challenges, and risks. Thunderbird International Business Review 61: 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouncken, Ricarda B., and Viktor Fredrich. 2016. Learning in coopetition: Alliance orientation, network size, and firm types. Journal of Business Research 69: 1753–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno Cyrino, Alvaro, Erika Penido Barcellos, and Betania Tanure. 2010. International trajectories of Brazilian companies: Empirical contribution to the debate on the importance of distance. International Journal of Emerging Markets 5: 358–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, Andrea, Massimiliano Matteo Pellegrini, Marina Dabic, and Leo-Paul Dana. 2016. Internationalization of firms from Central and Eastern Europe. European Business Review 28: 630–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlos, Zalaf Caseiro Luiz, and Gilmar Masiero. 2014. OFDI promotion policies in emerging economies: The Brazilian and Chinese strategies. Critical Perspectives on International Business 10: 237–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassiman, Bruno, and Elena Golovko. 2011. Innovation and internationalization through exports. Journal of International Business Studies 42: 56–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casson, Mark, and Mohammed Azzim Gulamhussen. 2004. Internationalization—Real Options, Knowledge Management and the Uppsala Approach. In The Challenge of International Business. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Vergara, Mauricio, Alejandro Alvarez-Marin, and Dario Placencio-Hidalgo. 2018. A bibliometric analysis of creativity in the field of business economics. Journal of Business Research 85: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavusgil, S. Tamer, and Erin Cavusgil. 2012. Reflections on international marketing: Destructive regeneration and multinational firms. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 40: 202–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavusgil, S. Tamer, and Gary Knight. 2015. The born global firm: An entrepreneurial and capabilities perspective on early and rapid internationalization. Journal of International Business Studies 46: 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, Yanto. 2017. A time-based process model of international entrepreneurial opportunity evaluation. Journal of International Business Studies 48: 423–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Sea-Jin, and Brian Wu. 2014. Institutional barriers and industry dynamics. Strategic Management Journal 35: 1103–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Sea-Jin, and Jay Hyuk Rhee. 2011. Rapid FDI expansion and firm performance. Journal of International Business Studies 42: 979–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charkaoui, Abdelkabir, Abdellah Ait Ouahman, and Brahim Bouayad. 2012. Modeling the Logistics Performance in Developing Countries: An exploratory study of Moroccan context. International Journal of Academic Research 4: 129–35. [Google Scholar]

- Charoensukmongkol, Peerayuth. 2016. The interconnections between bribery, political network, government supports, and their consequences on export performance of small and medium enterprises in Thailand. Journal of International Entrepreneurship 14: 259–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Jieke, M. P. Carlos Sousa, and Xinming He. 2016. The Determinants of Export Performance: A Review of the Literature 2006–2014. International Marketing Review 33: 626–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Hsiang-Lin, and Carol Yeh Yun Lin. 2009. Do as the large enterprises do? Expatriate selection and overseas performance in emerging markets: The case of Taiwan SMEs. International Business Review 18: 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Yung-Ming. 2008. Asset specificity, experience, capability, host government intervention, and ownership-based entry mode strategy for SMEs in international markets. International Journal of Commerce and Management 18: 207–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetty, Sylvie K., and Loren Stangl. 2010. Internationalization and innovation in a network relationship context. European Journal of Marketing 44: 1725–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child, John, Linda Hsieh, Said Elbanna, Joanna Karmowska, Svetla Marinova, Pushyarag Puthusserry, Terence Tsai, Rose Narooz, and Yunlu Zhang. 2017. SME international business models: The role of context and experience. Journal of World Business 52: 664–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Youn Kyaei, and Sang Suk Lee. 2018. A study on development strategy of Korean hidden champion firm: Focus on SWOT/AHP technique utilizing the competitiveness index. Journal of International Entrepreneurship 16: 547–75. [Google Scholar]

- Chung-Yuan, Benjamin Jian, Henrik Tai Ping Chiu, Kun Ming Kao, and Ching Wei Lin. 2009. A new business model for the gift industry in Taiwan. European Business Review 21: 472–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieślik, Jerzy, Eugene Kaciak, and Dianne H. B. Welsh. 2012. The impact of geographic diversification on export performance of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Journal of International Entrepreneurship 10: 70–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, Oscar F., Jorge Carrillo, and Jorge Alonso. 2012. Local Entrepreneurship within Global Value Chains: A Case Study in the Mexican Automotive Industry. World Development 40: 1013–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coviello, Nicole. 2015. Re-thinking research on born globals. Journal of International Business Studies 46: 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cravens, David W., Nigel F. Piercy, and Artur Baldauf. 2009. Management framework guiding strategic thinking in rapidly changing markets. Journal of Marketing Management 25: 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo-Cazurra, Alvaro, and Luis Alfonso Dau. 2009. Promarket reforms and firm profitability in developing countries. Academy of Management Journal 52: 1348–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo-Cazurra, Alvaro, and Mehmet Genc. 2008. Transforming disadvantages into advantages: Developing-country MNEs in the least developed countries. Journal of International Business Studies 39: 957–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabić, Marina, Jane Maley, Leo-Paul Dana, Ivan Novak, Massimiliano M. Pellegrini, and Andrea Caputo. 2019. Pathways of SME internationalization: A bibliometric and systematic review. Small Bus Econ 55: 705–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dau, Luis Alfonso. 2013. Learning across geographic space: Pro-market reforms, multi-nationalization strategy, and profitability. Journal of International Business Studies 44: 235–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, Dirk, Harry J. Sapienza, R. Isil Yavuz, and Lianxi Zhou. 2012. Learning and knowledge in early internationalization research: Past accomplishments and future directions. Journal of Business Venturing 27: 143–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Zilaing, Ruey-Jer Bryan Jean, and Rudolf R. Sinkovics. 2017. Polarizing effects of early exporting on exit. Management International Review 57: 243–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Minin, Alberto, Jieyin Zhang, and Peter Gammeltoft. 2012. Chinese foreign direct investment in R&D in Europe: A new model of R&D internationalization? European Management Journal 30: 189–203. [Google Scholar]

- Dikova, Desislava, Andreja Jaklič, Anže Burger, and Aljaž Kunčič. 2016. What is beneficial for first-time SME-exporters from a transition economy: A diversified or a focused export-strategy? Journal of World Business 51: 185–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirisu, I. Joy, Iyiola Oluwole, and O. S. Ibidunni. 2013. Product differentiation: A tool of competitive advantage and optimal organizational performance. European Scientific Journal 9: 258–81. [Google Scholar]

- Dirk, Clercq, Lianxi Zhou, and Aiqi Wu. 2016. Unpacking the relationship between young ventures’ international learning effort and performance in the context of an emerging economy. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 12: 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- Dodgson, Mark, Lei Guo, Mark Zhang, David Gann, and Hogn Cai. 2018. Seizing windows of opportunity by using technology-building and market-seeking strategies in tandem: Huawei’s sustained catch-up in the global market. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 36: 849–79. [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez, Noémie, and Ulrike Mayrhofer. 2015. Internationalization stages of traditional SMEs: Increasing, decreasing and re-increasing commitment to foreign markets. International Business Review 26: 1051–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encyclopedia. 2019. Emerging And Transition Economies: Widening The Poverty Gap. Available online: https://www.encyclopedia.com/international/news-and-education-magazines/emerging-and-transition-economies-widening-poverty-gap (accessed on 14 March 2020).

- Enderwick, Peter. 2009. Responding to global crisis: The contribution of emerging markets to strategic adaptation. International Journal of Emerging Markets 4: 358–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eryiğit, Nimet, Harun Demirkaya, and Gürol Özcüre. 2012. Multinational Firms as Technology Determinants in the New Era Developing Countries: Survey in Turkey. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences 58: 1239–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- European Commission. 2021. SME Definition. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/smes/sme-definition_en (accessed on 14 March 2020).

- Fan, Di, Lin Cui, Yi Li, and Cherrie J. Zhu. 2016. Localized learning by emerging multinational enterprises in developed host countries: A fuzzy-set analysis of Chinese foreign direct investment in Australia. International Business Review 25: 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrucci, Luca, Marina Gigliotti, and Andrea Runfola. 2017. Italian firms in emerging markets: Relationships and networks for internationalization in Africa. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship 30: 375–95. [Google Scholar]

- Filippov, Sergey. 2010. Russian companies: The rise of new multinationals. International Journal of Emerging Markets 5: 307–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foresgren, M., and J. Johanson. 1992. Managing Internationalization in Business Networks. Managing Networks in International Business 10: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Francioni, Barbara, Alessandro Pagano, and Davide Castellani. 2016. Drivers of SMEs’ exporting activity: A review and a research agenda. Multinational Business Review 24: 194–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredendall, Lawrence D., Peter Letmathe, and Nadine Uebe-Emden. 2016. Supply chain management practices and intellectual property protection in China: Perceptions of Mittelstand managers. International Journal of Operations & Production Management 36: 135–63. [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielsson, Mika, and Peter Gabrielsson. 2011. Internet-based sales channel strategies of born global firms. International Business Review 20: 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielsson, Mika, V. H. Manek Kirpalani, Pavlos Dimitratos, Carl Arthur Solberg, and Antonella Zucchella. 2008. Born globals: Propositions to help advance the theory. International Business Review 17: 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galimberti, Maurício Floriano, and Raul Sidnei Wazlawick. 2015. Active Internationalization of Small and Medium—Sized Software Enterprises—Cases of French Software Companies. Journal of Technology Management & Innovation 10: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- García-Cabrera, Antonia Mercedes, María Gracia García-Soto, and Juan José Durán-Herrera. 2016. Opportunity motivation and SME internationalisation in emerging countries: Evidence from entrepreneurs’ perception of institutions. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 12: 879–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, Ajai, and Mukesh Kumar. 2018. A systematic approach to conducting review studies: An assessment of content analysis in 25years of IB research. Journal of World Business 53: 280–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Gloria L., and Daniel Z. Ding. 2008. A strategic analysis of surging Chinese manufacturers: The case of Galanz. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 25: 667–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghauri, Pervez, Fatima Wang, Ulf Elg, and Veronica Rosendo-Ríos. 2016. Market driving strategies: Beyond localization. Journal of Business Research 69: 5682–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannoulakis, Chrysostomos, and Artemisia Apostolopoulou. 2011. Implementation of a multi-brand strategy in action sports. Journal of Product & Brand Management 20: 171–81. [Google Scholar]

- Glavas, Charmaine, and Shane Mathews. 2014. How international entrepreneurship characteristics influence Internet capabilities for the international business processes of the firm. International Business Review 23: 228–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Perez, Maria Alejandra, and Juan Fernando Velez-Ocampo. 2014. Targeting one’s own region: Internationalisation trends of Colombian multinational companies. European Business Review 26: 531–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, S., and P. Ganeshkumar. 2013. Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis: Understanding the Best Evidence in Primary Healthcare. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care 2: 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubbi, Sathyajit R., Preet S. Aulakh, Sougata Ray, M. B. Sarkar, and Raveendra Chittoor. 2010. Do international acquisitions by emerging-economy firms create shareholder value? The case of Indian firms. Journal of International Business Studies 41: 397–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, Heiko, and Mário Franco. 2015. When small businesses go international: Alliances as a key to entry. Journal of Business Strategy 36: 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddoud, Mohamed Yacine, Paul Jones, and Robert Newbery. 2017. Export promotion programs and SMEs’ performance: Exploring the network promotion role. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 24: 68–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, Michael G., Timothy S. Kiessling, and R. Glenn Richey. 2008. Global social time perspectives in marketing: A strategic reference point theory application. International Marketing Review 25: 146–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashai, Niron. 2011. Sequencing the expansion of geographic scope and foreign operations by “born global” firms. Journal of International Business Studies 42: 995–1015. [Google Scholar]

- Hashim, Fariza. 2015. SMEs’ impediments and developments in the internationalization process: Malaysian experiences. World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development 11: 100–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, Guillermo Jesus Larios. 2018. Patterns in international ICT entrepreneurship: Mexico’s case. Academia Revista Latinoamericana de Administración 31: 633–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewerdine, Lisa Jane, Maria Rumyantseva, and Catherine Welch. 2014. Resource scavenging: Another dimension of the internationalisation pattern of high-tech SMEs. International Marketing Review 31: 237–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilmersson, Mikael. 2012. Experiential knowledge types and profiles of internationalizing small and medium-sized enterprises. International Small Business Journal 32: 802–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisrich, R. D., M. P. Peters, and D. A. Shepherd. 2017. Entrepreneurship, 10th ed. Boston: McGraw Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Hitt, M. A., D. Li, and K. Xu. 2016. International strategy: From local to global and beyond. Journal of World Business 51: 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Paul, Ma Ga Yang, and David D. Dobrzykowski. 2014. Strategic customer service orientation, lean manufacturing practices and performance outcomes: An empirical study. Journal of Service Management 25: 699–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopsdal Hansen, Gard. 2008. Taking the mess back to business: Studying international business from behind. Critical Perspectives on International Business 4: 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsua, Chia-Wen, Homin Chen, and Lichung Jen. 2008. Resource linkages and capability development. Industrial Marketing Management 37: 677–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibeh, Kevin, Juliette Wilson, and Amon Chizema. 2012. The internationalization of African firms 1995–2011: Review and implications. Thunderbird International Business Review 54: 411–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowska, Barbara, and Cezary Główka. 2016. Clusters on the road to internationalization—Evidence from a CEE economy. Competitiveness Review 26: 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javalgi, Rajshekhar (Raj) G., and Patricia R. Todd. 2011. Entrepreneurial orientation, management commitment, and human capital: The internationalization of SMEs in India. Journal of Business Research 64: 1004–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakumar, Tulsi. 2017. Air Asia India: Competing for airspace in an emerging economy. Competitiveness Review: An International Business Journal 27: 516–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaram, Jayanth, Mita Dixit, and Jaideep Motwani. 2014. Supply chain management capability of small and medium sized family businesses in India: A multiple case study approach. International Journal of Production Economics 147: 472–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, So Won. 2016. Types of foreign networks and internationalization performance of Korean SMEs. Multinational Business Review 24: 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, Jan, and Finn Wiedersheim-Paul. 1975. The Internationalization of the Firm—Four Swedish Cases. Journal of Management Studies 12: 305–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, Jan, and Jan-Erik Vahlne. 1990. The mechanism of internationalization. International Marketing Review 7: 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, Jan, and Jan-Erik Vahlne. 1977. The Internationalization Process of the Firm: A Model of Knowledge Development and Increasing Foreign Market Commitments. Journal of International Business Studies 8: 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, Jan, and Jan-Erik Vahlne. 2003. Business relationship learning and commitment in the internationalization process. Journal of International Entrepreneurship 1: 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, Jan, and Jan-Erik Vahlne. 2006. Commitment and opportunity development in the internationalization process: A note on the Uppsala internationalization process model. Management International Review 46: 165–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, Jan, and Jan-Erik Vahlne. 2009. The Uppsala internationalization process model revisited: From liability of foreignness to liability of outsidership. Journal of International Business Studies 40: 1411–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Julius H., Jr., Bindu Arya, and Dinesh A. Mirchandani. 2013. Global integration strategies of small and medium multinationals: Evidence from Taiwan. Journal of World Business 48: 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johri, Lalit M., and Phallapa Petison. 2008. Value-based localization strategies of automobile subsidiaries in Thailand. International Journal of Emerging Markets 3: 140–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Marc T. 2009. A celebrity chef goes global: The business of Eating. Journal of Business Strategy 30: 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jormanainen, Irina, and Alexei Koveshnikov. 2012. International activities of emerging market firms. Management International Review 52: 691–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinic, Igor, and Cipriano Forza. 2012. Rapid internationalization of traditional SMEs: Between gradualist models and born Globals. International Business Review 21: 694–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, Wesley, Reggy Hooghiemstra, and Mary K. Feeney. 2018. Formal institutions, informal institutions, and red tape: A comparative study. Public Admin 96: 386–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Zaheer, and Yong Kyu Lew. 2018. Post-entry survival of developing economy international new ventures: A dynamic capability perspective. International Business Review 27: 149–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, Amit K., Peter K. Schott, and Shang-Jin Wei. 2013. Trade liberalization and embedded institutional reform: Evidence from Chinese exporters. American Economic Review 103: 2169–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khavul, Susanna, Liliana Pérez-Nordtvedt, and Eric Wood. 2010. Organizational entrainment and international new ventures from emerging markets. Journal of Business Venturing 25: 104–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Bowon. 2013. Competitive priorities and supply chain strategy in the fashion industry. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal 16: 214–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Angella Jiyoung, and Eunju Ko. 2010. Impacts of Luxury Fashion Brand’s Social Media Marketing on Customer Relationship and Purchase Intention. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing 11: 164–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, Gary A., and S. Tamar Cavusgil. 2004. Innovation, organizational capabilities, and the born-global firm. Journal of International Business Studies 35: 124–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontinen, Tanja, and Arto Ojala. 2010. Internationalization pathways of family SMEs: Psychic distance as a focal point. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 17: 437–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsakienė, Renata, Aušra Liučvaitienė, Monika Bužavaitė, and Agnė Šimelytė. 2017. Intellectual capital as a driving force of internationalization: A case of Lithuanian SMEs. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues 4: 502–15. [Google Scholar]

- Korsakienė, Renata, Danuta Diskienė, and Rasa Smaliukienė. 2015. Institutional theory perspective and internationalization of firms. How institutional context influences internationalization of SMEs? Entrepreneurship and sustainability issues 2: 142–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, T. N., and Hugh Scullion. 2017. Talent management and dynamic view of talent in small and medium enterprises. Human Resource Management Review 27: 431–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnaswamy, K. N., M. Mathirajan, and M. H. Bala Subrahmanya. 2014. Technological innovations and its influence on the growth of auto component SMEs of Bangalore: A case study approach. Technology in Society 38: 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriz, Alexandra, and Catherine Welch. 2018. Innovation and internationalisation processes of firms with new-to-the-world technologies. Journal International Business Studies 49: 496–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuivalainen, Olli, Sami Saarenketo, and Kaisu Puumalainen. 2012a. Start-up patterns of internationalization: A framework and its application in the context of knowledge-intensive SMEs. European Management Journal 30: 372–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuivalainen, Olli, Sami Saarenketo, and A. Ojala. 2012b. Internationalization pathways among family-owned SMEs. International Marketing Review 29: 496–518. [Google Scholar]

- Kujala, Irene, and Jan-Ake Törnroos. 2018. Internationalizing through networks from emerging to developed markets with a case study from Ghana to the U.S.A. Industrial Marketing Management 69: 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laghzaoui, Soulaimane. 2011. SMEs’ internationalization: An analysis with the concept of resources and competencies. Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 1: 181–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, Carmen, Grace K. S. Ho, and Rab Law. 2015. How can Asian hotel companies remain internationally competitive. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 27: 827–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Qingxin, and Songxu Wu. 2010. An empirical study of entrepreneurial orientation and degree of internationalization of small and medium-sized Chinese manufacturing enterprises. Journal of Chinese Entrepreneurship 2: 53–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Hyunsuk, Donna Kelley, Jangwoo Lee, and Sunghun Lee. 2012. SME survival: The impact of internationalization, technology resources, and alliances. Journal of Small Business Management 50: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leseure, M., and T. Driouchi. 2010. Exploitation versus exploration in multinational firms: Implications for the future of international business. Future Journal 42: 937–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Li, L., Gongmign Qian, and Zhengmign Qian. 2015. Speed of internationalization: Mutual effects of individual- and company-level antecedents. Global Strategy Journal 5: 303–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Xin, and Jens Gammelgaard. 2014. An integrative model of internationalization strategies: The corporate entrepreneurship—Institutional environment—Regulatory focus (EIR) framework. Critical Perspectives on International Business 10: 152–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, Francisco, and Alain Fayolle. 2015. A systematic literature review on entrepreneurial intentions: Citation, thematic analyses, and research agenda. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 11: 907–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, Ru-Shiun, Mike Chen-ho Chao, and Alan Ellstrand. 2017. Unpacking Institutional Distance: Addressing Human Capital Development and Emerging-Market Firms’ Ownership Strategy in an Advanced Economy. Thunderbird International Business Review 59: 281–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Xiaohui, Jiangyong Lu, Igor Filatotchev, Trevor Buck, and Mike Wright. 2010. Returnee entrepreneurs, knowledge spillovers and innovation in high-tech firms in emerging economies. Journal of International Business Studies 41: 1183–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, Luis, Sumit K. Kundu, and Luciano Ciravegna. 2009. Born global or born regional? Evidence from an exploratory study in the Costa Rican software industry. Journal of International Business Studies 40: 1228–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Yadong, and Juan Bu. 2018. Contextualizing international strategy by emerging market firms: A composition-based approach. Journal of World Business 53: 337–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksimov, Vladislav, Stephanie Lu Wang, and Yadong Luo. 2017. Institutional imprinting, entrepreneurial agency, and private firm innovation in transition economies. Journal of World Business 52: 854–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolova, Tatiana S., Ivan M. Manev, and Bojidar S. Gyoshev. 2010. In good company: The role of personal and inter-firm networks for new-venture internationalization in a transition economy. Journal of World Business 45: 257–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini Thomé, Karim, Janann Joslin Medeiros, and Bruce A. Hearn. 2017. Institutional distance and the performance of foreign subsidiaries in Brazilian host market. International Journal of Emerging Markets 12: 279–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, Joseph C., Anna Lupina-Wegener, and Susan Schneider. 2017. Internationalization strategies of emerging market banks: Challenges and opportunities. Business Horizons 60: 715–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matanda, Jekanyika Matanda. 2012. Internationalization of established small manufacturers in a developing economy: A case study of Kenyan SMEs. Thunderbird International Business Review 54: 509–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, Gerald A., and Rafael A. Corredoira. 2010. Network composition, collaborative ties, and upgrading in emerging-market firms: Lessons from the Argentine autoparts sector. Journal of International Business Studies 41: 308–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuser, Jeremy D., William L. Gardner, Jessica E. Dinh, Jinyu Hu, Robert C. Liden, and Robert G. Lord. 2016. A Network Analysis of Leadership Theory: The Infancy of Integration. Journal of Management 42: 1374–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milelli, Christian, Francoise Hay, and Yunnan Shi. 2010. Chinese and Indian firms in Europe: Characteristics, impacts and policy implication. International Journal of Emerging Markets 5: 377–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milosevic, Miona. 2018. Skills or networks? Success and fundraising determinants in a low performing venture capital market. Research Policy 47: 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misati, Everlynes, Fred O. Walumbwa, Somnath Lahiri, and Sumit K. Kundu. 2017. The Internationalization of African Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs): A South-North Pattern. Africa Journal of Management 3: 53–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moccia, M. 2015. Real or Passive Internationalization? The Analysis of the Kitchen Hoods Sector Lets Us Show the Advantages of the Strategic Approach. Available online: https://www.exportplanning.com/en/magazine/article/2018/11/05/internationalization-passive-real/ (accessed on 14 March 2020).

- Moore, Samuel B., and Susan L. Manring. 2009. Strategy development in small and medium sized enterprises for sustainability and increased value creation. Journal of Cleaner Production 17: 276–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, Flávio, and Mário Franco. 2018. The role of cooperative alliances in internationalization strategy: Qualitative study of Portuguese SMEs in the textile sector. Journal of Strategy and Management 11: 461–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mtshokotshe, Zwelethu. 2018. The Implementation of Human Resources Management Strategy within Restaurants in East London, South Africa. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure 7: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Musteen, Martina, Deepak K. Datta, and Marcus M. Butts. 2014. Do International Networks and Foreign Market Knowledge Facilitate SME Internationalization? Evidence from the Czech Republic. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 619: 749–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakos, George, Keith D. Brouthers, and Pavlos Dimitratos. 2014. International alliances with competitors and non-competitors: The disparate impact on SME international performance. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 8: 167–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narooz, Rose, and John Child. 2017. Networking responses to different levels of institutional void: A comparison of internationalizing SMEs in Egypt and the UK. International Business Review 26: 683–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narteh, Bedman, and George Acheampong. 2018. Foreign participation and internationalization intensity of African enterprises. International Marketing Review 35: 560–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoma, Mohammed, Abaho Ernest, Sudi Nangoli, and Kusemererwa Christopher. 2017. Internationalisation of SMEs: Does entrepreneurial orientation matter? World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development 13: 96–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, Shaista, Agyenim Boateng, Junjie Wu, and Mary Leung. 2012. Understanding the motives for SMEs entry choice of international entry mode. Marketing Intelligence & Planning 30: 717739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyuur, Richard B., Ružica Brecic, and Yaw A. Debrah. 2018. SME international innovation and strategic adaptiveness: The role of domestic network density, centrality and informality. International Marketing Review 35: 280–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odlin, Denis, and Maureen Benson-Rea. 2017. Competing on the edge: Implications of network position for internationalizing small- and medium-sized enterprises. International Business Review 26: 736–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguji, Nnamdi, and Richard Afriye Owusu. 2017. Acquisitions Entry Strategies in Africa: The Role of Institutions, Target-Specific Experience, and Host-Country Capabilities—The Case Acquisitions of Finnish Multinationals in Africa. Thunderbird International Business Review 59: 209–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, Arto, and Pasi Tyrväinen. 2009. Impact of psychic distance to the internationalization behaviour of knowledge-intensive SMEs. European Business Review 21: 263–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olabode, Oluwaseun Eniola, Ogechi Adeola, and Shahin Assadinia. 2018. The effect of export market-oriented culture on export performance: Evidence from a Sub-Saharan African economy. International Marketing Review 35: 637–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omri, Waleed, and Audrey Becuwe. 2014. Managerial characteristics and entrepreneurial internationalization: A study of Tunisian SMEs. Journal of International Entrepreneurship 12: 8–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oparaocha, Gospel Onyema. 2015. SMEs and international entrepreneurship: An institutional network perspective. International Business Review 24: 861–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei-Bonsu, Nana. 2014. Quantitative Analysis of Managerial Capabilities and Internationalization of Manufacturing SMEs—Empirical Evidence from Developing Countries. Journal of Management Research 6: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Outreville, J. François. 2012. A note on geographical diversification and performance of the world’s largest reinsurance groups. Multinational Business Review 20: 376–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovadje, Franca. 2016. The Internationalization of African Firms: Effects of Cultural Differences on the Management of Subsidiaries. Africa Journal of Management 2: 117–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangarkar, Nitin, and Jie Wu. 2013. Alliance formation, partner diversity, and performance of Singapore startups. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 30: 791–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattinson, Steven, David Preece, and Patrick Dawson. 2016. In search of innovative capabilities of communities of practice: A systematic review and typology for future research. Management Learning 47: 506–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, Justin, and Desislava Dikova. 2016. The Internationalization of Asian Firms: An Overview and Research Agenda. Journal of East-West Business 22: 237–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Paul, Justin, and Parul Gupta. 2014. Process and intensity of internationalization of IT firms—Evidence from India. International Business Review 23: 594–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, Justin, and Rosarito Sánchez-Morcilio. 2019. Toward a new model for firm internationalization: Conservative, predictable, and pacemaker companies and markets. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences 36: 336–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, V., Y. Temouri, J. Jyoti, and H. Chahal. 2020. A multi-level analysis of sustainable business practices in emerging countries. International Journal of Organizational Analysis 139: 1111–22. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, Susan E. 2014. When does prior experience pay? Institutional experience and the multinational corporation. Administrative Science Quarterly 59: 145–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, Catherine, and Jason Byrne. 2014. The benefits of publishing systematic quantitative literature reviews for PhD candidates and other early-career researchers. Higher Education Research & Development 33: 534–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhudesai, Rohit, and Ch. V. V. S. N. V. Prasad. 2017. Antecedents of SME alliance performance: A multi-level review. Management Research Review 40: 1261–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, Debasis, and Niladri Kundu. 2016. Distribution Strategy of a Global Firm in an Emerging Market: The Case of 3M India. Asian Case Research Journal 20: 219–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, Jaya Prakash, and Keshab Das. 2015. Regional export advantage of rising power SMEs: Analytics and determinants in the Indian context. Critical Perspectives on International Business 11: 236–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presutti, Manuela, Cristina Boari, and Luciano Fratocchi. 2016. The evolution of inter-organizational social capital with foreign customers: Its direct and interactive effects on SMEs’ foreign performance. Journal of World Business 51: 760–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puck, Jonas F., Dirk Holtbrügge, and Alexander T. Mohr. 2009. Beyond entry mode choice: Explaining the conversion of joint ventures into wholly owned subsidiaries in the People’s Republic of Chin. Journal of International Business Studies 40: 388–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, Achal. 2008. Going global and taking charge: The road ahead for the Indian manager. Vikalpa: The Journal for Decision Makers 33: 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, Mahfuzur, Moshfique Uddin, and George Lodorfos. 2017. Barriers to enter in foreign markets: Evidence from SMEs in Emerging market. International Marketing Review 34: 68–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramamurti, Ravi. 2012. What is really different about emerging market multi-nationals. Global Strategy Journal 2: 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramamurti, Ravi, and Peter J. Williamson. 2018. Rivalry between emerging-market MNEs and developed-country MNEs: Capability holes and the race to the future. Business Horizons, Elsevier 62: 157–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, Jase R., Livia Barakat, Matthew C. Mitchell, Thomas Ganey, and Olesea Voloshin. 2016. The effects of past satisfaction and commitment on the future intention to internationalize. International Journal of Emerging Markets 11: 256–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, Y. V., and Subhash S. Naik. 2011. Determinants of Goan SME Firms Going Global: Theoretical and Empirical Approach. Vikalpa: The Journal for Decision Makers 36: 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribau, Claudia P., António Carrizo Moreira, and Mario Raposo. 2018a. SME Internationalization Research: Mapping the State of the Art. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences 35: 280–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribau, Claudia P., António Carrizo Moreira, and Mario Raposo. 2018b. Internacionalização de PME no Continente Americano: Revisão da Literatura. Innovar 28: 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugman, Alan M., and Chang Hoon Oh. 2008. The international competitiveness of Asian firms. Journal of Strategy and Management 1: 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzzier, Mitja, Robert D. Hisrich, and Bostjan Antoncic. 2006. SME internationalization research: Past, present, and future. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 13: 476–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva, Leena, and Devjani Chatterjee. 2018. The Fall and Rise of Cotton Yarn ‘Manja. Global Business Review 19: 790–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahaym, Arvin, and Daeil Nam. 2013. International diversification of the emerging-market enterprises: A multi-level examination. International Business Review 22: 421–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, Susanne, and Hans Jansson. 2014. Collective internationalization—A new take off route for SMEs from China. Journal of Asia Business Studies 8: 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoonjans, Bilitis, Philippe Van Cauwenberge, and Heidi Vander Bauwhede. 2013. Formal business networking and SME growth. Small Business Economics 41: 169–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsuddoha, A. K., M. Yunus Ali, and Nelson Oly Ndubisi. 2009. Impact of government export assistance on internationalization of SMEs from developing nations. Journal of Enterprise Information Management 22: 408–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharabi, Moshe. 2014. Today’s quality is tomorrow’s reputation and the following day’s business success. Total Quality Management and Business Excellence 25: 183–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Yanhong, and Robert Handfield. 2012. Talent management issues for multinational logistics companies in China: Observations from the field. International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications 15: 163–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinkle, George A., and Aldas P. Kriauciunas. 2010. Institutions, size and age in transition economies: Implications for export growth. Journal of International Business Studies 41: 267–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singal, Ajay, and Arun Kumar Jain. 2012. Outward FDI trends from India: Emerging MNCs and strategic issues. International Journal of Emerging Markets 7: 443–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Gurmeet, Raghuvar D. Pathak, and Rafia Naz. 2010. Issues faced by SMEs in the internationalization process: Results from Fiji and Samoa. International Journal of Emerging Markets 5: 153–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Nitya, and Paul Hong. 2017. From Local to Global: Developing a Business Model for Indian MNCs to Achieve Global Competitive Advantage. Journal of Asia-Pacific Business 18: 192–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoian, M. Cristina, Alex Rialp, Josep Rialp, and Robin Jarvis. 2016. Internationalisation of Central and Eastern European small firms: Institutions, resources and networks. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 23: 105–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strategic Direction. 2014. The underdog bites back: How emerging market multinationals succeed in global markets. Strategic Direction 30: 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Ortega, Sonia María, Antonia Mercedes García-Cabrera, and Gary Alan Knight. 2015. Knowledge acquisition for SMEs first entering developing economies: Evidence from Senegal. European Journal of Management and Business Economics 25: 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symeonidou, Noni, Johan Bruneel, and Erkko Autio. 2017. Commercialization strategy and internationalization outcomes in technology-based new ventures. Journal of Business Venturing 32: 302–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Yee Kwan. 2011. The Influence of networking on the internationalization of SMEs: Evidence from internationalized Chinese firms. International Small Business Journal 29: 374–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepjun, Chidapa. 2016. Factors Affecting Market Entry Modes of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) to China—A Multiple Case Study of Thai SMEs. European Journal of Business and Management 8: 78–85. [Google Scholar]

- The Economist. 2017. Defining Emerging Markets: A self-Fulfilling Prophecy. Special Report. October 5, 2017 Edition. Available online: https://www.economist.com/special-report/2017/10/05/defining-emerging-markets (accessed on 14 March 2020).

- Torkkeli, Lasse, Olli Kuivalainen, Sami Saarenketo, and Kaisu Puumalainen. 2016. Network competence in Finnish SMEs: Implications for growth. Baltic Journal of Management 11: 207–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, David, David Denyer, and Palminder Smart. 2003. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. British Journal of Management 14: 207–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vuuren, Jurie, and Nadin Worgotter. 2013. Market driving behaviour in organisations. South African. Journal of Economic and Management Sciences 16: 115–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, Sumati. 2011. Born global acquirers from Indian IT: An exploratory case study. International Journal of Emerging Markets 6: 351–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wah, Sheh Seow, and Michael Teo Chee Meng. 2011. The effects of agency costs among interfirm alliances: A study of Singapore small-and medium-sized enterprises (SMES) in China. International Journal of Management 28: 379–90. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Yihan, Ari Van Assche, and Ekaterina Turkina. 2018. Antecedents of SME embeddedness in inter-organizational networks: Evidence from China’s aerospace industry. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship 30: 53–75. [Google Scholar]

- White, Lyal, and Kathryn Van Dongen. 2017. Internationalization of South African Retail Firms in Selected African Countries. Journal of African Business 18: 278–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Christopher, Ana Colovic, and Jiqing Zhu. 2016. Foreign Market Knowledge, Country Sales Breadth and Innovative Performance of Emerging Economy Firms. International Journal of Innovation Management 20: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, Peter J. 2015. The competitive advantages of emerging market multinationals: A re-assessment. Critical Perspectives on International Business 11: 216–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. 2004. Economies in Transition Economies in Transition: An OED Evaluation of World Bank Assistance”, The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/14885/302640PAPER0Economies0in0transition.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 14 March 2020).

- Wu, Aiqi, and Hinrich Voss. 2015. When does absorptive capacity matter for international performance of firms? Evidence from China. International Business Review 24: 344–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Jun, Xufei Ma, Jane W. Lu, and Daphne W. Yiu. 2014. Outward foreign direct investment by emerging market firms: A resource dependence logic. Strategic Management Journal 35: 1343–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yener, Müjdelen, Barış Doğruoğlu, and Sinem Ergun. 2014. Challenges of Internationalization for SMEs and Overcoming these Challenges: A case study from Turkey. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences 150: 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohari, Tony. 2017. The Uppsala Internationalization Model and Its Limitation in the New Era. [online]. Available online: http://www.digitpro.co.uk/2012/06/21/the-uppsala-internationalization-model-and-its-limitation-in-the-new-era/ (accessed on 14 March 2020).

- Zhang, Man, Patriya Tansuhaj, and James McCullough. 2009. International entrepreneurial capability: The measurement and a comparison between born global firms and traditional exporters in China. Journal of International Entrepreneurship 7: 292–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Xiao, Xufei Ma, Yue Wang, Xin Li, and Dong Huo. 2016. What drives the internationalization of Chinese SMEs? The joint effects of international entrepreneurship characteristics, network ties, and firm ownership. International Business Review 25: 522–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Congcong, Susanna Khavul, and Dilene Crockett. 2012. Does it transfer? The effects of pre-internationalization experience on post-entry organizational learning in entrepreneurial Chinese firms. Journal of International Entrepreneurship 10: 232–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Lianxi, and Aiqi Wu. 2014. Earliness of internationalization and performance outcomes: Exploring the moderating effects of venture age and international commitment. Journal of World Business 49: 132–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Lianxi, Bradley R. Barnes, and Yuan Lu. 2010. Entrepreneurial proclivity, capability upgrading and performance advantage of newness among international new ventures. Journal of International Business Studies 41: 882–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Nan, and Mauro F. Guillén. 2015. From home country to home base: A dynamic approach to the liability of foreignness. Strategic Management Journal 36: 907–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Ying, Malcolm Warner, and Deepak Sardana. 2020. Internationalization and destination selection of emerging market SMEs: Issues and challenges in a conceptual framework. Journal of General Management 45: 206–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Li, and Xueqian Chen. 2017. The effect of code-sharing alliances on airline profitability. Journal of Air Transport Management 58: 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucchella, Antonella, and Giovanna Magnani. 2016. Theoretical Foundations of International Entrepreneurship: Strategic Management Studies. In International Entrepreneurship, Theoretical Foundation and Practices, 2nd ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors and Years of Publications | Journals | Number of Articles |

|---|---|---|

| Hernandez (2018) | Academia Revista Latinoamericana de Administración | 1 |

| Cuervo-Cazurra and Dau (2009) | Academy of Management Journal | 1 |

| Perkins (2014) | Administrative Science Quarterly | 1 |

| Mtshokotshe (2018) | African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure | 1 |

| Ovadje (2016); Misati et al. (2017) | African Journal of Management | 2 |

| Khandelwal et al. (2013) | American Economic Review | 1 |

| Ge and Ding (2008); Pangarkar and Wu (2013); Dodgson et al. (2018) | Asia Pacific Journal of Management | 3 |

| Pradhan and Kundu (2016) | Asian Case Research Journal | 1 |

| Amdam (2009) | Business History | 1 |

| Torkkeliet al. (2016) | Baltic Journal of Management | 1 |

| Ramamurti and Williamson (2018); Marques et al. (2017) | Business Horizons | 2 |

| Jankowska and Główka (2016) | Competitiveness Review | 1 |

| Jayakumar (2017) | Competitiveness Review: An International Business Journal | 1 |

| Hopsdal Hansen (2008); Annushkina and Colonel (2013); Carlos and Masiero (2014); Pradhan and Das (2015); Williamson (2015); Adegbile and Sarpong (2018); Berko (2018) | Critical perspectives on international business | 7 |

| Korsakienė et al. (2015, 2017) | Entrepreneurship and sustainability issues | 2 |

| Musteen et al. (2014) | Entrepreneurship theory and practice | 1 |

| Ojala and Tyrväinen (2009); Chung-Yuan et al. (2009); Amal and Rocha (2010); Gonzalez-Perez and Velez-Ocampo (2014) and Caputo et al. (2016) | European Business Review | 5 |

| Tepjun (2016) | European Journal of Business and Management | 1 |

| Suárez-Ortega et al. (2015) | European Journal of Management and Business Economics | 1 |

| Chetty and Stangl (2010) | European Journal of Marketing | 1 |

| Kuivalainen et al. (2012a); Di Minin et al. (2012) | European Management Journal | 2 |

| Leseure and Driouchi (2010) | Future Journal | 1 |

| Sachdeva and Chatterjee (2018) | Global Business Review | 1 |

| Ramamurti (2012); Li et al. (2015) | Global Strategy Journal | 2 |

| Bhattacharya and Michael (2008) | Harvard Business Review | 1 |

| Krishnan and Scullion (2017) | Human Resource Management Review | 1 |

| Boehe et al. (2016) | Industrial Marketing Management | 1 |

| Gabrielsson et al. (2008); Cheng and Yun Lin (2009); Gabrielsson and Gabrielsson (2011), Kalinic and Forza (2012); Sahaym and Nam (2013); Glavas and Mathews (2014); Paul and Gupta (2014); Dominguez and Mayrhofer (2015); Oparaocha (2015); Wu and Voss (2015); Fan et al. (2016); Zhang et al. (2016); Narooz and Child (2017); Odlin and Benson-Rea (2017); Khan and Lew (2018) | International Business Review | 15 |

| Dirk et al. (2016); García-Cabrera et al. (2016) | International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal | 2 |

| Hsua et al. (2008); Andersen et al. (2009); Kujala and Törnroos (2018) | Industrial Marketing Management | 3 |

| Charkaoui et al. (2012) | International Journal of Academic Research | 1 |

| Cheng (2008) | International Journal of Commerce and Management | 1 |

| Lam et al. (2015) | International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management | 1 |

| Johri and Petison (2008); Enderwick (2009); Bruno Cyrino et al. (2010); Filippov (2010); Milelli et al. (2010); Singh et al. (2010); Varma (2011); Singal and Jain (2012); Ramsey et al. (2016); Marini Thomé et al. (2017) | International Journal of Emerging Markets | 10 |

| Williams et al. (2016) | International Journal of Innovation Management | 1 |

| Shi and Handfield (2012) | International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications | 1 |

| Wah and Meng (2011) | International Journal of Management | 1 |

| Fredendall et al. (2016) | International Journal of Operations and Production Management | 1 |

| Jayaram et al. (2014) | International Journal of Production Economics | 1 |

| Harvey et al. (2008); Chen et al. (2016); Kuivalainen et al. (2012b); Hewerdine et al. (2014); Rahman et al. (2017); Amankwah-Amoah et al. (2018); Anning-Dorson (2018); Narteh and Acheampong (2018); Nyuur et al. (2018); Olabode et al. (2018) | International Marketing Review | 10 |

| Tang (2011) | International Small Business Journal | 1 |

| Anderson (2011); White and Van Dongen (2017) | Journal of African Business | 2 |

| Zou and Chen (2017) | Journal of Air Transport Management | 1 |

| Sandberg and Jansson (2014); Ahmad (2014) | Journal of Asia Business Studies | 2 |

| Singh and Hong (2017) | Journal of Asia–Pacific Business | 1 |

| Javalgi and Todd (2011); Bouncken and Fredrich (2016) | Journal of Business Research | 2 |

| Jones (2009); Haase and Franco (2015) | Journal of Business Strategy | 2 |

| Khavul et al. (2010); Symeonidou et al. (2017) | Journal of Business Venturing | 2 |

| Lan and Wu (2010) | Journal of Chinese Entrepreneurship | 1 |

| Moore and Manring (2009) | Journal of Cleaner Production | 1 |

| Shamsuddoha et al. (2009) | Journal of Enterprise Information Management | 1 |

| Paul and Dikova (2016) | Journal of East–West Business | 1 |

| Cuervo-Cazurra and Genc (2008); Lopez et al. (2009); Puck et al. (2009); Bhaumik et al. (2010); Gubbi et al. (2010); Shinkle and Kriauciunas (2010); Zhou et al. (2010); Liu et al. (2010); McDermott and Corredoira (2010); Chang and Rhee (2011); Dau (2013); Coviello (2015) | Journal of International Business Studies | 12 |

| Zhang et al. (2009); Zheng et al. (2012); Omri and Becuwe (2014); Charoensukmongkol (2016); Anwar (2017); Chung and Lee (2018) | Journal of International Entrepreneurship | 6 |

| Cravens et al. (2009) | Journal of marketing management | 1 |

| Giannoulakis and Apostolopoulou (2011) | Journal of Product and Brand Management | 1 |

| Hong et al. (2014) | Journal of Service Management | 1 |

| Ferrucci et al. (2017); Wang et al. (2018) | Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship | 2 |

| Kontinen and Ojala (2010); Berger and Herstein (2015); Stoian et al. (2016); Haddoud et al. (2017) | Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development | 4 |

| Rugman and Hoon Oh (2008); Morais and Franco (2018) | Journal of Strategy and Management | 2 |

| Cavusgil and Cavusgil (2012) | Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science | 1 |

| Manolova et al. (2010); Johnson et al. (2013); Zhou and Wu (2014); Dikova et al. (2016); Hitt et al. (2016); Presutti et al. (2016); Maksimov et al. (2017); Luo and Bu (2018) | Journal of World Business | 8 |

| Ambos et al. (2009); Athreye et al. (2014) | Long Range Planning | 2 |

| Jormanainen and Koveshnikov (2012); Deng et al. (2017) | Management International Review | 2 |

| Al-Hyari et al. (2012); Nisar et al. (2012) | Marketing Intelligence and Planning | 2 |

| Outreville (2012); Francioni et al. (2016); Jeong (2016) | Multinational Business Review | 3 |

| Eryiğit et al. (2012); Yener et al. (2014) | Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences | 2 |

| Kaufmann et al. (2018) | Public Administration | 1 |

| Kim (2013) | Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal | 1 |

| Milosevic (2018) | Research Policy | 1 |

| Ribau et al. (2018a) | Innovar | 1 |

| Bai et al. (2018) | Scandinavian Journal of Management | 1 |

| Schoonjans et al. (2013) | Small Business Economics | 1 |

| Van Vuuren and Worgotter (2013) | South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences | 1 |

| Strategic Direction (2014) | Strategic Direction | 1 |

| Nakos et al. (2014) | Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal | 1 |

| Chang and Wu (2014); Xia et al. (2014); Zhou and Guillén (2015); Bednarek and Jarzabkowski (2018) | Strategic Management Journal | 4 |

| Krishnaswamy et al. (2014) | Technology in Society | 1 |

| Amoako and Matlay (2015) | The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation | 1 |

| Ibeh et al. (2012); Matanda (2012); Oguji and Owusu (2017); Liou et al. (2017); Boso et al. (2018) | Thunderbird International Business Review | 5 |

| Sharabi (2014) | Total quality management and business excellence | 1 |

| Raghavan (2008); Reddy and Naik (2011) | Vikalpa: The Journal for Decision Makers | 2 |

| Contreras et al. (2012) | World Development | 1 |

| Hashim (2015); Ngoma et al. (2017) | World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development | 2 |

| Total | 183 |

| Factors | Description of Barriers | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Institutional–legal environment | Firms are disadvantaged due to the weak external factors such as weak institutional and legal system. | Berko (2018); Paul and Dikova (2016); Perkins (2014); Tepjun (2016); Kaufmann et al. (2018); Singh et al. (2010); Khandelwal et al. (2013); Berko (2018); Caputo et al. (2016); Zhou and Guillén (2015); Shinkle and Kriauciunas (2010); Al-Hyari et al. (2012); Rahman et al. (2017); Marini Thomé et al. (2017) |

| Unfamiliarity hazards and liability of foreignness | Unfamiliarity hazards and liability of foreignness develops from the lack of the ‘learning by doing approach’. | Marques et al. (2017); Symeonidou et al. (2017); Chen et al. (2016); Marques et al. (2017); Musteen et al. (2014); Tepjun (2016); Ramsey et al. (2016) |

| Limited network relationships | Firms have a limited international network which prevents incremental internationalization or radical internationalization. | Amal and Rocha (2010); Chetty and Stangl (2010); Tang (2011); Bai et al. (2018); Francioni et al. (2016); Torkkeli et al. (2016); Haase and Franco (2015); Sandberg and Jansson (2014) |

| Limited technological capability | Technological backwardness lead to competitive disadvantages | Filippov (2010); Di Minin et al. (2012); Ramamurti and Williamson (2018); Hewerdine et al. (2014); Morais and Franco (2018) |

| Small firm Size | Firm level characteristics such as firm size and sophistication of local demand continue to influence firms’ efforts at exporting or entering a foreign market | Singh et al. (2010); Milelli et al. (2010); Varma (2011); Singal and Jain (2012); Pradhan and Das (2015); Berko (2018); Jayakumar (2017) |

| Cultural or Entrepreneurial orientation (EO) | The EO or attitudes of managers or founders are inextricably linked to firm’s internationalization strategy or practice such as pro-active, risk-taking, and innovative behaviour | Anning-Dorson (2018); Anderson (2011); Li et al. (2015); Chandra (2017); Haddoud et al. (2017) |

| Differences in resource endowments | Competitive advantages differ from those of developed market firms due to their differences in national resource endowments | Jormanainen and Koveshnikov (2012); Krishnan and Scullion (2017); Jankowska and Główka (2016) |

| Cultural differences, geographical and psychological distance | Cultural distance, geographical and psychological distance defined as the set of the cultural and linguistic differences create a high internal uncertainty that affect firms’ performance and capability to internationalize | Bruno Cyrino et al. (2010); Tepjun (2016); Ovadje (2016); Jankowska and Główka (2016); Harvey et al. (2008); Chung-Yuan et al. (2009); Kontinen and Ojala (2010); Ojala and Tyrväinen (2009); Gonzalez-Perez and Velez-Ocampo (2014); Marini Thomé et al. (2017) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Igwe, P.A.; Rugara, D.G.; Rahman, M. A Triad of Uppsala Internationalization of Emerging Markets Firms and Challenges: A Systematic Review. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12010003

Igwe PA, Rugara DG, Rahman M. A Triad of Uppsala Internationalization of Emerging Markets Firms and Challenges: A Systematic Review. Administrative Sciences. 2022; 12(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleIgwe, Paul Agu, David Gamariel Rugara, and Mahfuzur Rahman. 2022. "A Triad of Uppsala Internationalization of Emerging Markets Firms and Challenges: A Systematic Review" Administrative Sciences 12, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12010003

APA StyleIgwe, P. A., Rugara, D. G., & Rahman, M. (2022). A Triad of Uppsala Internationalization of Emerging Markets Firms and Challenges: A Systematic Review. Administrative Sciences, 12(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12010003