Abstract

This research aimed to analyze the moderating effect that Protestant work ethics (PWE) have on the relationship between human resources practices (HRP) and (a) work engagement (WE) and (b) organizational citizenship behavior (OCB). The sample consisted of 299 participants. The results revealed that PWE moderates the relationship between HRP and WE and OCB through five dimensions. The dimensions of PWE-leisure and PWE-centrality of work are moderators between the HRP and the WE. The dimensions of PWE-morality–ethics, PWE-wasted time, PWE-delay of gratification, and PWE-leisure moderate the relationship between HRP and OCB. The analysis offers additional evidence to existing literature in understanding how human resources practices facilitate the development of work engagement and citizenship behaviors. The workers’ values play an essential role here to strengthen that relationship and mitigate its harmful effects.

1. Introduction

The world of work has undergone constant and complex changes due to the rapid transition from industrial processes to technology and new ways of living and working. This means that, with an eye on organizational sustainability and growth in the face of aggressive and demanding competition, both academics and professionals are obliged to try to better understand the variables that impact the strategic objectives of the organization, as well as the performance and well-being of the employees (Urbini et al. 2020).

To face a complex socioeconomic environment like the current one, companies can resort to promoting some individual behaviors such as work engagement (WE) and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB), as long as the latter is practiced in a balanced way considering its positive and negative effects for the organizational, professional and personal development of its employees (Bolino et al. 2003).

The empirical evidence leaves no doubt about the critical role of work engagement in generating results produced by employees, teams, and organizations (Bakker and Albrecht 2018). Work engagement is characterized by generating a cognitive, physical, and emotional connection in employees that connects them with their work even when they are outside of the working space/environment or when it is outside of their regular working hours (Schaufeli et al. 2002). On the other hand, the performance of the context is also relevant in the achievement of organizational objectives. Along these lines, organizational citizenship behaviors have become one of the fundamental elements for explaining this type of behavior. These organizational citizenship behaviors refer to discretionary and additional behaviors shown by workers and are not part of the expected or formal requirements of a position (Organ 1988), but rather imply various “spontaneous/non-compulsory” behaviors that do not usually appear in job descriptions but are valued by managers to promote the effective functioning of the organization (Organ 1997). Different academics have shown how these organizational citizenship behaviors are relevant in achieving organizational objectives (Khalili 2017; Organ 2018).

In the generation of OCBs and WE in individuals and groups, human resources practices (HRP) play a fundamental role. There is clear evidence showing the association and effect of human resources practices with and on work engagement and organizational citizenship behavior (Bakker and Leiter 2010; Thanigaivel et al. 2017). In this context, different studies show the importance that the perceptions and expectations of employees have in the success of human resources practices (Ostroff and Bowen 2000). The effect of these practices can vary from one environment to another, between different groups, and between individuals, since their impact is ultimately based on individual perceptions (Villajos et al. 2019). Work values strongly influences these individual perceptions that employees place on work. In this sense, the Protestant work ethic is one of the most widely discussed and used constructs to study work values, considering that work is not only a means to receive rewards, but is also rewarding by itself; it is also opposed to leisure, the unnecessary spending of money, wasting time, and even sociability (Weber 1958; Furnham 1984).

However, to our knowledge, no study has tried to analyze the influence that work values have on the effectiveness of human resources practices to develop work engagement and organizational citizenship behaviors. Researching this question is relevant from three points of view. First, it allows us to know the most effective human resources practices that promote the WE and the OCB development. Second, organizational behavior can be explained more accurately through the work values that people place on work. Finally, guidelines are provided for HR professionals to maximize the effect of HRP on WE and OCB.

In line with the above, the objective of this work is to investigate how Protestant Work Ethics influence the relationship between human resources practices and work engagement and organizational citizenship behaviors.

2. Theoretical Foundation

2.1. Work Engagement (WE) and Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB)

WE and OCB are two of the constructs of work psychology that are used most frequently to explain the performance of individuals in organizational contexts (Mallick et al. 2014; Khalili 2017).

WE is defined as a positive, satisfactory, and work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption (Schaufeli et al. 2002). More than a specific and momentary state, this concept refers to a more persistent and influential affective and cognitive state that is not focused on a particular object, event, individual, or behavior (Schaufeli et al. 2002; Schaufeli and Bakker 2010). Instead, it describes the degree of relationship employees have with their work in considering it as part of their life. To this end, Kanungo (1982) identifies three basic behaviors: (a) physical involvement in which high labor participation is observed; (b) cognitive attachment in which a potent identification of the employee with his work is shown; and (c) the emotional attachment in which the employee thinks about work even when they are not there. Thus, WE is relevant for explaining the performance of employees and their commitment to the organization.

Furthermore, managers have continuously expressed that achieving higher performance is a critical success factor (Cesário and Chambel 2017). However, the degree to which individuals manifest themselves can vary depending on working conditions, personal characteristics, strategies to regulate behavior, the passing of time, and the situation (Bakker 2014; Bakker and Albrecht 2018). For example, strong WE behaviors are more likely to be evident at the organizational level when workers face significant challenges with sufficient work and personal resources (Tadić et al. 2015). In this context, human resources practices play a very relevant role, both in building these labor resources, referring to those physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of work that are functional for achieving the objectives, as well as in building personal resources related to those aspects that help to achieve the objectives and reduce the demand for employment and that often stimulate personal growth and development (Bakker and Demerouti 2007).

On the other hand, OCBs refer to discretionary acts shown by workers that help develop the social and psychological environment in which tasks are carried out (Organ 1997, 2018). These behaviors include helping others, assuming additional responsibilities, working overtime, and defending the organization (Organ et al. 2006). They also take part in the company’s effective operation by contributing to the progress of its social capital and specifically to the creation of structural, relational, and cognitive forms of social capital (Bolino et al. 2002).

Various types and dimensions of OCB have been proposed. For example, the two-dimensional model (Williams and Anderson 1991; Finkelstein and Penner 2004) states that there are two types of OCB: (a) those directed toward individuals and (b) those directed toward the organization. The first includes behaviors that have an immediate benefit for individuals, while the second addresses directly beneficial behaviors for the organization (Shaheen et al. 2016). Alternatively, Organ (1988) presents five factors: altruism, civic virtue, sportsmanship, courtesy, and awareness. The first dimension, altruism, includes those spontaneous behaviors aimed at helping other people with their tasks or with a problem related to the organization. Awareness leads to attending work and complying with the rules and procedures of the organization. The third dimension, sportsmanship, implies the willingness of people to tolerate undesirable working conditions without complaining about them. The fourth is courtesy, which includes consulting with other people before making decisions that may affect their work. Finally, civic virtue includes actions that indicate that people participate, get involved, and care about the organization’s life (Organ 1997). Different studies show how these OCBs are positively connected with organizational results (Khalili 2017), with the effectiveness of work teams (Podsakoff et al. 2009), with individual outputs such as burnout and job satisfaction (Torlak et al. 2021), and psychological empowerment and organizational justice (Singh and Singh 2018). However, although the positive qualities of OCBs are not discussed, in light of the evidence, authors such as Bolino et al. (2013) maintain that these behaviors could have negative consequences when they become normative, so the employees may experience ambiguity and role overload, job stress, and work-family conflict. The findings show that OCBs are primarily due to the personality traits of individuals (Methot et al. 2017). However, despite having a relatively stable trend over time, this kind of behavior can be influenced and modified by significant events (Methot et al. 2017). In this context, HRP play a fundamental role in attracting employees with this citizenship profile and generating working conditions to develop such behaviors.

2.2. The Role of Human Resources Practices (HRP) in the development of WE and OCB

HRP are crucial elements for building human capital and achieving the employees’ and the organization’s objectives (Bello-Pintado 2015). The literature has identified a varied number of HRP. Although there is still no agreement on which practices should be considered to establish a taxonomy (Toh et al. 2008), some authors have stated the importance of considering not only HRP aimed at improving performance and production, as has been traditionally done, but also those that include practices whose main objective is to support employees and promote their well-being and maintenance (Guest 2003; Posthuma et al. 2013). Employees are more likely to show positive work attitudes toward strategies that show that the organization cares about them (Luu et al. 2019). From this point of view, Villajos et al. (2019) consider that the measurement of HRP should include two packages of interdependent practices. The first package is focused on performance (HRP-P) and includes: (1) training and development, (2) contingent pay and rewards, (3) performance evaluation, (4) recruitment and selection, and (5) competitive salary. The second, which is oriented toward employee support (HRP-S), is composed of (6) job security, (7) work–life balance, and (8) exit management practices.

Several studies have been carried out on the impact of HRP at individual, group, and organizational levels. For example, at the individual level, the findings show that HRP are strongly related to two of the three WE factors: vigor and dedication (Bakker and Demerouti 2007; Bakker and Leiter 2010). Specifically, the degree to which WE manifests is influenced by some HRP, such as job redesign (Holman and Axtell 2016), training opportunities, professional development opportunities, performance evaluation (Ahmed et al. 2020), and job security (Karatepe and Olugbade 2016). Likewise, the findings reveal that WE is related to the quality of the organizational leadership style (Oliveira and Rocha 2017) and leads to a lower intention to rotate (Memon et al. 2016) and miss work (Karatepe and Olugbade 2016). Ultimately, the evidence shows that HRP have a significant impact on the WE of employees (Aboramadan et al. 2019); therefore, their proper management by organizations not only at the individual level but through a strategic approach can enhance the degree to which WE is shown at the collective level (Barrick et al. 2015).

In contrast, evidence regarding the relationship between HRP and OCB is more limited. However, the findings reveal that hiring and selection practices (Begum et al. 2014) and training and development practices (Nawangsari and Sutawidjaya 2018; Rubel and Rahman 2018), as well as job security and the general perception of HRP have a positive and significant effect on OCB (Thanigaivel et al. 2017). Therefore, employers should ensure human resources practices that promote the development of OCBs in the workplace regarding a long-term employment relationship (Begum et al. 2014). Undoubtedly, because of the positive relationship of OCB with individual and organizational performance, there is a growing concern among organizations and managers to improve this behavior (Mallick et al. 2014).

2.3. Protestant Work Ethic (PWE), HRP, WE, and OCB

The value that employees place on work is essential for understanding the individual behaviors of workers and their involvement in their performance and the success of organizations (Van Ness et al. 2010). One of the most widely used constructs to refer to this general attitude of employees toward work is the Protestant work ethic (PWE; Miller et al. 2002).

PWE has its roots in the studies of Weber (1958) who stated that one of the central aspects of work is the value that people give it. Thus, he considers that work is not only a means of receiving rewards, but that it is rewarding in itself and contrary to leisure, the unnecessary spending of money, wasting time, and even social relationships, which were thought of as banal and mundane acts (Furnham 1984). Although its origins are tied to robust religious beliefs, it was during the “Protestant Reformation” that hard work, including physical and mental work, became important to all individuals in society (Hill 1992). Today it appears that what was initially conceived as a religious construct is now probably secular (i.e., not associated with religion) and is best viewed as a general work ethic that maintains the term “Protestant work ethic” due to the time at which it was coined.

The PWE identifies people who have general attitudes toward work characterized by what Weber (1930) called “the vocation,” which consists of an acceptance of the fulfillment of the obligations imposed on the individual through a position in the world that implies overcoming worldly pleasures and using time productively. Currently, the concept of PWE appears to be ingrained in popular culture and recognized as an essential determinant of work-related behavior (Miller et al. 2002). The findings of Miller et al. (2002) conceptualize PWE as a set of beliefs and attitudes that reflect the fundamental value of work and propose it as a multidimensional and comprehensive construct composed of seven dimensions—centrality of work, morality–ethics, wasted time, delay of gratification, leisure, hard work, and self-reliance—that explain how individuals perceive the importance of work, free time, morality, and the fulfillment of duty.

PWE has proven to explain different organizational behaviors and attitudes (Hite et al. 2015). For example, the presence of a high work ethic predicts the development of OCB (Mohammad et al. 2016), strengthens job satisfaction (Leong et al. 2014) and reduces turnover intention (Khan et al. 2015; Rawwas et al. 2018). Also, the findings support a positive and significant relationship between OCB and two dimensions of PWE: (a) hard work associated with organizational helping behaviors, and (b) self-reliance (Ryan 2002). In addition, workers with a high work ethic adapt and easily face any challenge related to their job or task (Khan et al. 2015). In fact, the success of organizations in highly changing environments like those of today requires employees who are committed to the job (Gorgievski-Duijvesteijn et al. 1998). Additionally, PWE has been proven to play a moderating role between different work attitudes and behaviors. For example, it helps explain the relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment (Pillay 2015), or the relationship between employee perception of organizational policy and their work attitudes (Khan et al. 2015). From a cross-cultural perspective, work-related values and attitudes have been studied, showing the differences associated with PWE (Tang et al. 2003)

Therefore, it seems reasonable to argue that the PWE will play a relevant role in explaining the relationship between HRP and WE and OCB. Specifically, we argue a moderation effect in which the PWE will influence the relationship between HRP and WE and OCB. When HRP are deficient and cannot facilitate the generation of behaviors related to WE and OCB, the PWE will act to mitigate these effects. Hence, even in the absence of HRP facilitators of WE and OCB, individuals with high PWE will develop more WE and OCB behaviors than those employees with low PWE. Current literature considers PWE in a unidimensional manner (e.g., Furnham 1984; Ryan 2002; Gorgievski-Duijvesteijn et al. 1998; Tang et al. 2003). However, a deeper understanding of the role played by PWE can be obtained by linking the different PWE dimensions with the relations between HRP and WE and OCB.

Considering previous literature (e.g., Mohammad et al. 2016; Pillay 2015; Ryan 2002) and the content analysis of the PWE dimensions, we argue that those PWE dimensions related to the intensity of dedication to work (centrality of work, hard work, wasted time, and leisure) will moderate the relationship between HRP and WE. While, on the other hand, PWE dimension related to morality–ethics will moderate the relationship between HRP and OCB. Thus, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

The PWE dimensions centrality of work (H1a), hard work (H1b), wasted time (H1c), and leisure (H1d) interact significantly with HRP-P in the prediction of WE.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

The PWE dimensions centrality of work (H2a), hard work (H2b), wasted time (H2c), and leisure (H2d) interact significantly with HRP-S in the prediction of WE.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

The PWE dimensions morality–ethics interact significantly with HRP-P in the prediction of OCB.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

The PWE dimensions morality–ethics interact significantly with HRP-S in the prediction of OCB.

Finally, based on literature or content analysis we cannot establish specific hypotheses for the PWE dimensions of self-reliance and delay of gratification, so we propose the following research question:

RQ1: Does PWE dimension self-reliance and delay of gratification interact significantly with the HRP in the prediction of WE and/or OCB? Does the same interaction effects occur for HRP-P and HRP-S?

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

Two hundred ninety-nine subjects participated in the study who were selected in a propositional way and who met the following inclusion criteria established for this study at the time of collecting the information: (a) currently working or having worked (b) for a minimum time of 12 months consecutively (c) in a full-time position. In terms of sex, 46% of the subjects were men and the rest women. The average age was 37.7 years with a standard deviation of 9.44 points. Furthermore, 81.9% of the participants worked in private establishments while 15.4% worked in public institutions; the remaining subjects (2.7%) were linked to companies of a mixed nature.

3.2. Measures

HRP. HRP measurement was performed using the HRP Scale (Villajos et al. 2019). This scale in the Spanish language provides two measures: HRP-P (performance improvement practices) and HRP-S (employee support practices). It is made up of 24 items: 15 correspond to performance improvement practices (α = 0.940; ω = 0.941) and nine correspond to support practices (α = 0.896; ω = 0.896), with response options provided on a 5-point Likert scale where (1) is “nothing” to (5) is “much.” For example, “My organization or company offers me an incentive and rewards plan linked to my performance.”

WE. WE was measured using the validated version in Spanish (Schaufeli et al. 2002) of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES). It consists of 17 items that score on a 7-point Likert scale where (0) is “never” and (6) is “always.” An example of an item on the scale is “When I am working, I forget everything that happens around me.” According to the authors, UWES can yield three partial scores, corresponding to each subscale and a total score. For this study, we considered only the total score. The total score has shown adequate reliability (α = 0.929; ω = 0.937). In addition, we check unidimensionality by means of Confirmatory Factor Analysis in order to use only the single total score. Results showed an acceptable model-fit (Byrne 2016) for the unidimensional solution (see Appendix A).

OCB. OCB was measured using the Organizational Citizenship Behavior Scale (ECCO; Rosario-Rodríguez et al. 2019). The 15 items that make up the scale are scored in a Likert-type response format that ranges from (1) “Totally disagree” to (6) “Totally agree.” An example of an item on the scale is “I do my best to maintain quality standards.” Originally, this scale has five factors (altruism, sportsmanship, civic virtue, conscientiousness and courtesy); however, Rosario-Rodríguez et al. (2019) suggest that it is possible to have an average calculated from the five factors. Therefore, we considered only the average of the five factors. The scale has shown adequate reliability (α = 0.888; ω = 0.899). In addition, we check unidimensionality by means of Confirmatory Factor Analysis in order to use only the single average score. Results showed an acceptable model-fit (Byrne 2016) for the unidimensional solution (see Appendix A).

PWE. PWE measurement was carried out through a reduced version of the Ecuadorian adaptation of the Multidimensional Work Ethic Profile (MWEP; Meriac et al. 2013) developed by Zúñiga et al. (2019). The scale has 28 items distributed equally in the seven dimensions. A Likert-type questionnaire with five points was used where (1) corresponds to “Totally disagree” and (5) to “Totally agree.” An example of an item on the scale is “A hard day’s work gives me a feeling of accomplishment.” The reliability of the dimensions (Zúñiga et al. 2019) is adequate, receiving the following: delay of gratification (α = 0.777; ω = 0.786), hard work (α = 0.813; ω = 0.820), self-reliance (α = 0.676; ω = 0.679), morality–ethics (α = 0.578; ω = 0.585), leisure (α = 0.712; ω = 0.715), centrality of work (α = 0.621; ω = 0.647) and wasted time (α = 0.596; ω = 0.642).

3.3. Procedure and Data Analysis

The measures were administered through Google Forms. Before the application, the participants filled out a consent form. The analysis of the results was carried out with the SPSS 25 program. The moderation effect model was used in the linear regression with the macro–SPSS PROCESS developed by Hayes (2017). The selected model has a 95% confidence interval and 5000 samples for bootstrapping.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Results

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics, the correlations between the study variables, and their reliability. The reliability of the measures is suitable for all of them (Alpha > 0.70) except for four dimensions of the PWE: centrality of work, morality–ethics, wasted time, and self-reliance. Regarding the inter-correlations, it is noted that they are high between WE and OCB (rxy ˃ 0.60, p < 0.01) and medium between these two variables and human resources practices. In contrast, the different dimensions of the PWE show positive and significant correlations with each other except for the leisure dimension, which correlates negatively with all other dimensions (except delay of gratification). The PWE and WE dimension correlations are significant and positive except for the leisure dimension (significant and negative correlation) and the self-reliance dimension (not significant). The correlations between the PWE and OCB dimensions are also significant and positive except for the leisure dimension (significant and negative correlation) and the self-reliance and delay of gratification dimensions (not significant). Finally, the PWE and HRP-P dimensions correlations are also significant and positive except for leisure and self-reliance (not significant). This same pattern of correlations is the one that occurs between the PWE and HRP-S dimensions.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and inter-correlations between the study variables.

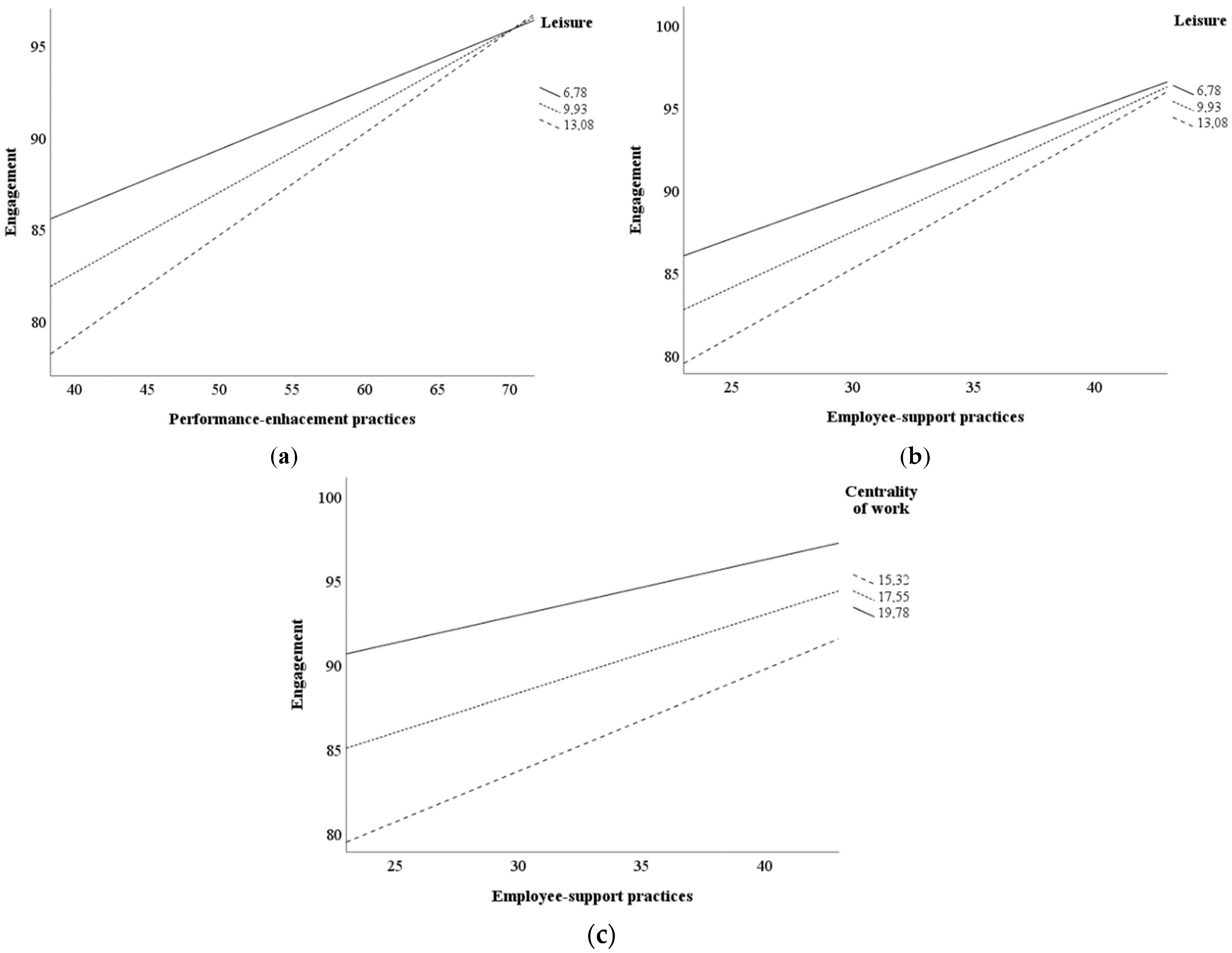

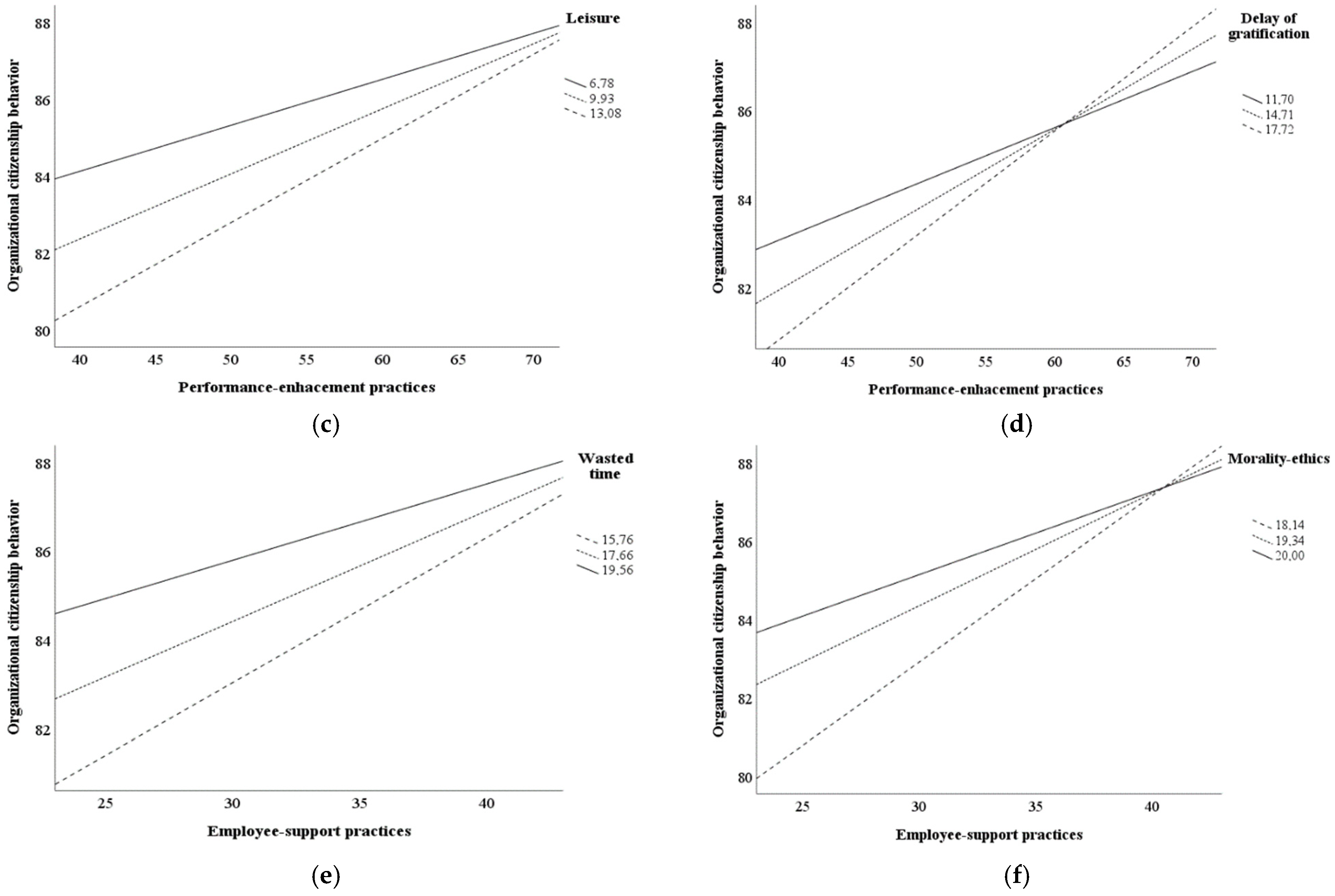

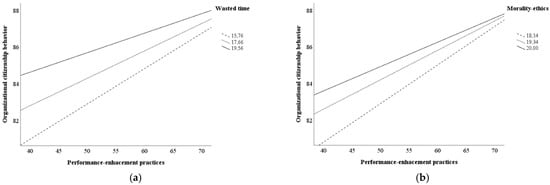

Table 2 shows the results obtained from the moderation analysis for the four primary relationships of the study: (a) HRP-P vs. WE, (b) HRP-S vs. WE, (c) HRP-P vs. OCB, and (d) HRP-S vs. OCB. Five of the seven dimensions of the PWE act as moderators of the relationship in the model. The leisure dimension moderates the relationship between HRP and WE, both in the case of HRP-P and HRP-S. In this way, the increase in HRP makes the existing differences in the relationship between HRP and WE disappear in individuals with low scores in the leisure dimension. The dimension of centrality of work also has a moderating effect on the relationship between HRP-S and WE. The predictive level of the interaction between centrality of work and HRP-S is R2-chng = 0.0111 (p = 0.0226).

Table 2.

Moderation of the PWE in the relationship of HRP-P, HRP-S with WE, and OCB.

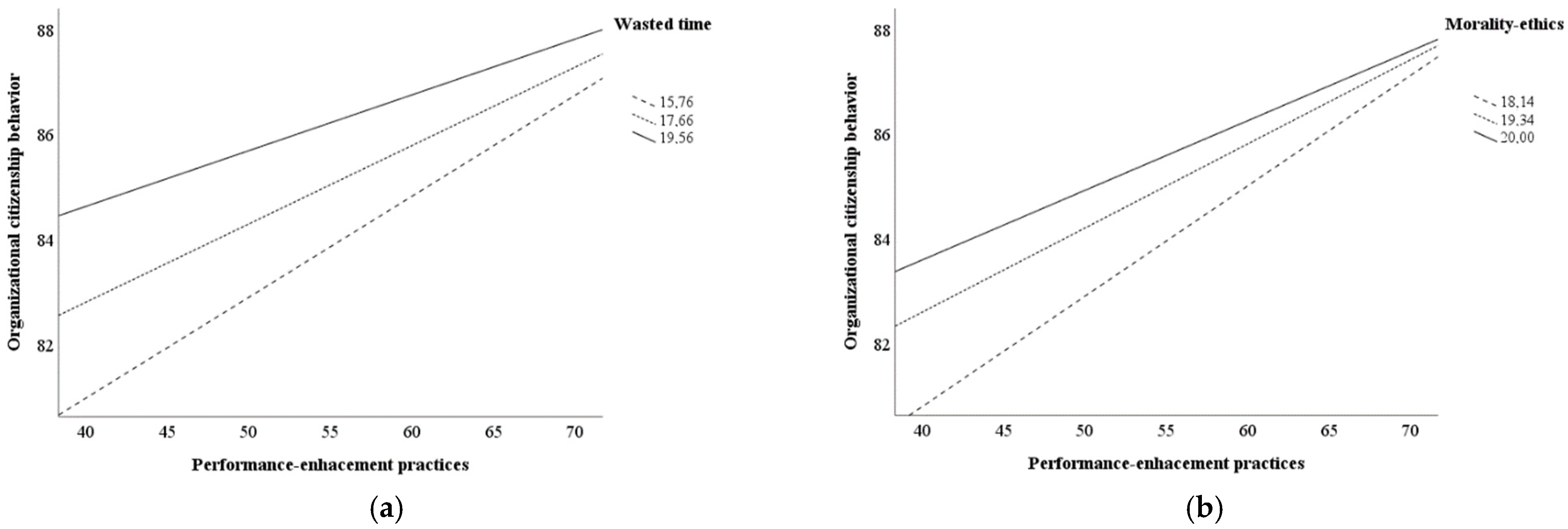

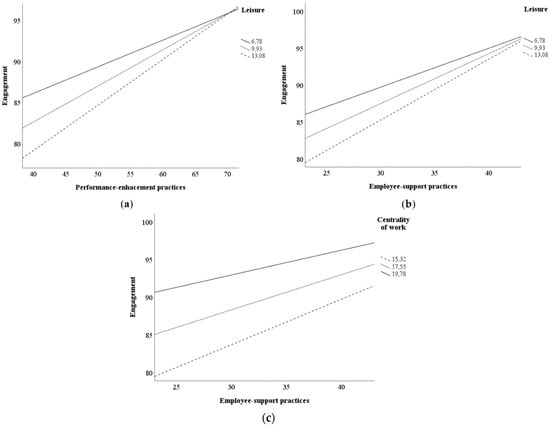

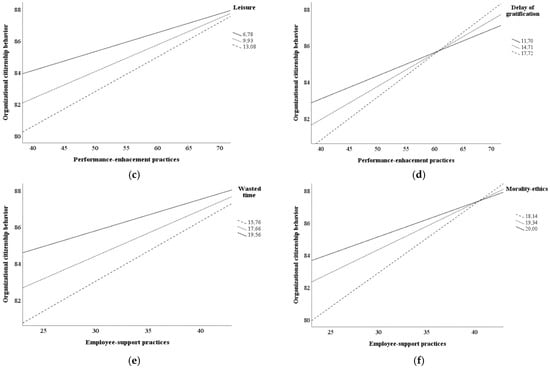

Regarding the OCB, as explained from the HRP, it was found that the PWE has two moderating dimensions. First, it is shown that morality–ethics and wasted time moderate the relationship for both HRP-P and HRP-S. Additionally, the delay of gratification and leisure moderate the relationship between HRP-P and OCB.

These results give partial support to the first two hypotheses raised. The moderation effects raised in H1 are supported for PWE dimension leisure (H1d) but not for PWE dimensions centrality of work (H1a), hard work (H1b), and wasted time (H1c). Likewise, the moderation effects proposed in H2 are also supported for the PWE dimensions centrality of work (H2a) and leisure (H2d) but not for the PWE dimensions hard work (H2b) and wasted time (H2c). On the other hand, the moderation effects raised in H3 and H4 are supported: PWE dimension morality–ethics moderates the relationship between HRP-P and OCB (H3) and between HRP-S and OCB (H4).

Figure 1.

HRP-PWE moderations to predict work engagement. Note. In Figure 1, three interaction diagrams are observed. Diagram (a) shows the variation in the leisure main effect and the interaction of this dimension with HRP-P. In diagram (b), there is variation in leisure’s main effect and the interaction of this dimension with HRP-S. Finally, in diagram (c), a variation of main effects in HRP-S and centrally of work and the interaction of HRP-A and centrality of work is observed.

Figure 2.

HRP-PWE moderations to predict Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Note. Six interaction diagrams are shown in Figure 2. Diagram (a) shows the variation in the main effects of HRP-P and wasted time and the interaction of these two variables. Diagram (b) shows variation in the main effects of HRP-P and morality–ethics and variation in the interaction of these two variables. In (c) it can be seen that the variation occurs only in the main effect of leisure and in the interaction of this variable with HRP-P. In (d) it can be observed that there is variation in the main effect of delay of gratification and the interaction of this variable with HRP-P. (e) shows variations in the main effects of wasted time and HRP-S and the interaction of these two variables. Finally, (f) shows variations in the main effects of morality and ethics and HRP-S and the interaction of these two variables.

4.2. Discussion

The findings support the idea that PWE plays a relevant role in explaining the relationship between HRP-P and HRP-S with WE and OCB. The study shows that five of the seven dimensions of the PWE are relevant: leisure, centrality of work, delay of gratification, morality–ethics, and wasted time. Our data suggest that the leisure dimension plays a role in enhancing the negative effect produced in WE and OCBs due to the absence of good human resources practices. The rest of the relevant dimensions, on the other hand, act to facilitate the development of WE and OCB even in the case of deficient human resources practices. In this way, the PWE dimensions lose their effect when human resources practices are adequate. More specifically, our findings indicate how the leisure dimension has a moderating effect on the relationship between HRP-P and HRP-S with WE and between HRP-P and OCB. On the other hand, the centrality of work moderates the relationship between HRP-S and WE. Finally, delay of gratification moderates the relationship between HRP-P and OCB, and morality–ethics and wasted time moderate the relationship of HRP-P and HRP-S with the OCB.

Our results partially agree with the findings of Pillay (2015) who shows the moderating effect of two dimensions (leisure and delay of gratification) of PWE for the relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment. The fact that not all dimensions of PWE play the same role is also consistent with the findings of Hudspeth (2004) who concludes that there are dimensions of PWE that have a negative or non-significant relationship with organizational behaviors. In any case, our results seem to be in line with previous research in which work ethics acted as a moderator between the relationships of different individual and organizational variables (Khan et al. 2015; Mohammad et al. 2016; Rawwas et al. 2018). They are also consistent with the idea that the relationship between workers’ perceptions of policies and their work attitudes is moderated by work ethics (Khan et al. 2015). Our results have relevant practical implications. On the one hand, our findings indicate that human resources managers find a foundation that allows them to help explain why human resources practices that are developed to facilitate WE and OCBs can have a differential effect on workers. Furthermore, some dimensions of the PWE help develop the WE and OCB when human resources practices are deficient in facilitating performance. For example, support for employees offers lines of action for human resources professionals to consider using these dimensions in attracting talent. Suppose an organization with few supportive and performance practices selects individuals for whom leisure is a significant value; in this case, such practices will have a negative effect on WE and OCBs. But if the company incorporates employees whose values reinforce the importance of centrality of work, the delay of gratification, the rejection of wasted time, and morality–ethics; the negative effect on WE and the OCB will be limited by the absence of good human resources practices which aims to facilitate the performance and to support employees.

Finally, our study is not without limitations that can be addressed in subsequent studies. First, OCB and WE measurements originally are multidimensional; nevertheless, the authors of both scales suggest that it is possible to use each one as a dimension. We only considered the last option to perform our hypothesis and research question; however, future studies should verify the multidimensional measures, in order to prove the interaction effects of the PWE in the relation of HRP with the multidimensions of OCB and WE. Another one is that all the measurements in the study were taken in a convergent manner at the same time. However, a longitudinal approach is also required to include the temporal evolution of the found effects in the analysis. Additionally, study participants belong to a specific region with its own cultural and employment characteristics, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Therefore, new studies should examine how our findings are replicated with participants from other cultures and socio-occupational situations.

5. Conclusions

The study’s main objective was to analyze the degree to which the dimensions of the PWE moderate the relationship between human resources practices and work engagement and citizenship behaviors. Our analysis indicates how HRP facilitate the development of WE and OCB through the positive or negative moderating effect of PWE between HR and WE and OCB practices. Specifically, two of the seven dimensions of PWE moderate the relationship between HRP and work commitment: leisure and centrality of work; while the dimensions of morality–ethics, wasted time and delay of gratification moderate the relationship between HRP and OCB.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Z. and D.A.; methodology, C.Z., D.A. and P.C.-T.; validation, D.A.; formal analysis, P.C.-T.: investigation, C.Z.; resources, C.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, C.Z. and P.C.-T.; writing—review & editing, C.Z. and D.A.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding, but the APC was funded by Universidad Politécnica Salesiana.

Institutional Review Board Statement

No applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis–Fit Indexes for 1 Factor Solution (WE and OCB).

Table A1.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis–Fit Indexes for 1 Factor Solution (WE and OCB).

| x2/gl | GFI | AGFI | PGFI | NFI | RFI | RMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFA 1 Factor Solution–WE | 3.06 | 0.977 | 0.971 | 0.760 | 0.969 | 0.965 | 0.089 |

| CFA-1 Factor Solution–OCB- | 0.57 | 0.958 | 0.944 | 0.719 | 0.933 | 0.922 | 0.038 |

Note: Method Unweighted Least Squares (ULS); GFI—Goodnes of fit index; AGFI—adjusted GFI; PGFI—parsimony adjusted GFI; NFI—normed fit index; RFI—Bollen’s relative fit index; RMR—root mean square residual.

References

- Aboramadan, Mohammed, Belal Albashiti, Hatem Alharazin, and Khalid Abed Dahleez. 2019. Human resources management practices and organizational commitment in higher education: The mediating role of work engagement. International Journal of Educational Management 34: 154–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed Umair, Karibu Maitama Kura, Waheed Ali Umrani, and Munwar Hussain Pahi. 2020. Modelado del vínculo entre las prácticas de desarrollo de recursos humanos y el compromiso laboral: El papel de moderación del clima de servicio. Global Business Review 21: 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Arnold B. 2014. Daily fluctuations in work engagement: An overview and current directions. European Psychologist 19: 227–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Arnold B., and Evangelia Demerouti. 2007. The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology 22: 309–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Arnold B., and Michael P. Leiter, eds. 2010. Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research. London: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Arnold B., and Simon Albrecht. 2018. Work engagement: Current trends. Career Development International 23: 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrick, Murray. R., Gary R. Thurgood, Troy A. Smith, and Stephen H. Courtright. 2015. Collective organizational engagement: Linking motivational antecedents, strategic implementation, and firm performance. Academy of Management Journal 58: 111–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, S Sumayya, Sun Zehou, and Mohammad Amzad Hossain Sarker. 2014. Investigating the relationship between recruitment & selection Pactice and OCB dimensions of commercial banks in China. International Journal of Academic Research in Management 3: 9. [Google Scholar]

- Bello-Pintado, Alejandro. 2015. Bundles of HRM practices and performance: Empirical evidence from a Latin American context. Human Resource Management Journal 25: 311–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolino, M., Anthony Klotz, William Turnley, and Jaron Harvey. 2013. Exploring the Dark Side of Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior 34: 542–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolino, Mark C., William H. Turnley, and James. M. Bloodgood. 2002. Citizenship behavior and the creation of social capital in organizations. Academy of Management Review 27: 505–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolino, Mark C., William H. Turnley, and Todd Averett. 2003. Going the Extra Mile: Cultivating and Managing Employee Citizenship Behavior [and Executive Commentary]. The Academy of Management Executive (1993–2005) 17: 60–73. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, Barbara M. 2016. Structural Equation Modeling With AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 3rd ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cesário, Francisco, and Maria José Chambel. 2017. Linking organizational commitment and work engagement to employee performance. Knowledge and Process Management 24: 152–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, Marcia A., and Louis A. Penner. 2004. Predicting organizational citizenship behavior: Integrating the functional and role identity approaches. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal 32: 383–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, Adrian. 1984. The protestant work ethic: A review of the psychological literature. European Journal of Social Psychology 14: 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgievski-Duijvesteijn, Marjan, Herman Steensma, and Else Te Brake. 1998. Protestant Work Ethic as a moderator of mental and physical well-being. Psychological Reports 83: 1043–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guest, David. 2003. Human resource management, corporate performance and employee wellbeing: Building the worker into HRM. Journal of Industrial Relations 44: 335–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2017. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis, Second Edition: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Roger B. 1992. The Work Ethic as Determined by Occupation, Education, Age, Gender, Work Experience, and Empowerment. Doctoral dissertation, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Hite, Dwight M., Joshua J. Daspit, and Xueni Dong. 2015. Examining the influence of transculturation on work ethic in the United States. Cross Cultural Management 22: 145–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, David, and Carolyn Axtell. 2016. Can job redesign interventions influence a broad range of employee outcomes by changing multiple job characteristics? A quasi-experimental study. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 21: 284–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudspeth, Natasha. 2004. Examining the MWEP: Further Validation of the Multidimensional Work Ethic Profile. Undefined. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Examining-the-MWEP%3A-further-validation-of-the-work-Hudspeth/9d8b30228b3c9c2740dc46ba214cfcc88268cc69 (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Kanungo, Rabindra N. 1982. Measurement of job and work involvement. Journal of Applied Psychology 67: 341–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, Osman M., and Olusegun A. Olugbade. 2016. The mediating role of work engagement in the relationship between high-performance work practices and job outcomes of employees in Nigeria. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 28: 2350–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, Ashkan. 2017. Transformational leadership and organizational citizenship behavior: The moderating role of emotional intelligence. Leadership & Organization Development Journal 38: 1004–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Khurram, Muhammad Abbas, Asma Gul, and Usman Raja. 2015. Organizational justice and job outcomes: Moderating role of Islamic work ethic. Journal of Business Ethics 126: 235–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, Frederick T. L., Jason L. Huang, and Stanton Mak. 2014. Protestant Work Ethic, Confucian Values, and Work-Related Attitudes in Singapore. Journal of Career Assessment 22: 304–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, Trong Tuan, Chris Rowley, and Thanh Thao Vo. 2019. Addressing employee diversity to foster their work engagement. Journal of Business Research 95: 303–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, Eeman, Rabindra Kumar Pradhan, Hare Ram Tewari, and Lalatendu Kesari Jena. 2014. Comportamiento de ciudadanía organizacional, desempeño laboral y prácticas de recursos humanos: Una perspectiva relacional. Management and Labour Studies 39: 449–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, Muntaz Ali, Rohani Salleh, and Mohamed Noor Rosli Baharom. 2016. The link between training satisfaction, work engagement and turnover intention. European Journal of Training and Development 40: 407–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meriac, John, David Woehr, C. Allen Gorman, and Amanda Thomas. 2013. Development and validation of a short form for the Multidimensional Work Ethic Profile. Journal of Vocational Behavior 82: 155–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methot, Jessica R., David Lepak, Abbie J. Shipp, and Wendy R. Boswell. 2017. Good citizen interrupted: Calibrating a temporal theory of citizenship behavior. The Academy of Management Review 42: 10–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Michael J., David J. Woehr, and Natasha Hudspeth. 2002. The meaning and measurement of work ethic: Construction and initial validation of a multidimensional inventory. Journal of Vocational Behavior 60: 451–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, Jihad, Farzana Quoquab, and Rosmini Omar. 2016. Factors affecting organizational citizenship behavior among Malaysian bank employees: The moderating role of Islamic work ethic. Procedia -Social and Behavioral Sciences 224: 562–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nawangsari, Lenny Christina, and Ahmad Hidayat Sutawidjaya. 2018. The impact of human resources practices affecting organization citizenship behaviour with mediating job satisfaction in university. In Proceedings of the 3rd Annual International Seminar on Transformative Education and Educational Leadership (AISTEEL 2018). Paris: Atlantis Press, pp. 291–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, Lucia Barbosa de, and Juliana da Costa Rocha. 2017. Work engagement: Individual and situational antecedents and its relationship with turnover intention. Revista Brasileira de Gestão de Negócios 19: 415–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, Dennis W. 1988. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome. Lanham: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Organ, Dennis W. 1997. Organizational citizenship behavior: It’s construct clean-up time. Human Performance 10: 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, Dennis W. 2018. Organizational citizenship behavior: Recent trends and developments. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 5: 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, Dennis W., Philip Podsakoff, and Scott B. MacKenzie. 2006. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Its Nature, Antecedents, and Consequences. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Ostroff, Cheri, and David E. Bowen. 2000. Moving HR to a higher level: HR practices and organizational effectiveness. In Multilevel Theory, Research, and Methods in Organizations: Foundations, Extensions, and New Directions. Hoboken: Jossey-Bass, pp. 211–66. [Google Scholar]

- Pillay, Kirshia. 2015. Work ethic as a moderator between job satisfaction and organisational commitment in a South African sample. Ph.D. thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South African. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, Nathan P., Steven W. Whiting, Philip M. Podsakoff, and Brian D. Blume. 2009. Individual- and organizational-level consequences of organizational citizenship behaviors: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology 94: 122–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posthuma, Richard A., Michael C. Campion, Malika Masimova, and Michael A. Campion. 2013. A high performance work practices taxonomy: Integrating the literature and directing future research. Journal of Management 39: 1184–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawwas, Mohammed Y. A., Basharat Javed, and Muhammad Naveed Iqbal. 2018. Perception of politics and job outcomes: Moderating role of Islamic work ethic. Personnel Review 47: 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, Adam Rosario, Ramón Rodríguez Montalbán, and Miguel E. Martínez Lugo. 2019. Propiedades Psicométricas de la Escala de Comportamientos de Ciudadanía Organizacional (ECCO). Revista Puertoriqueña de Psicología 30: 30–46. [Google Scholar]

- Rubel, Md, and Md. H. Asibur Rahman. 2018. Effect of training and development on Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB): An evidence from private commercial banks in Bangladesh. Global Journal of Management and Business Research 18: 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, John J. 2002. Work Values and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors: Values That Work for Employees and Organizations. Journal of Business and Psychology 17: 123–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, Wilmar B., and Arnold B. Bakker. 2010. Defining and measuring work engagement: Bringing clarity to the concept. In Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research. London: Psychology Press, pp. 10–24. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, Wilmar B., Marisa Salanova, Vicente González-romá, and Arnold B. Bakker. 2002. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies 3: 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, Musarrat, Ritu Gupta, and Y. L. N. Kumar. 2016. Exploring dimensions of teachers’ OCB from stakeholder’s perspective: A Study in India. The Qualitative Report 21: 1095–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Sanjay Kumar, and Ajai Pratap Singh. 2018. Interplay of organizational justice, psychological empowerment, organizational citizenship behavior, and job satisfaction in the context of circular economy. Management Decision 57: 937–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadić, Maja, Arnold B. Bakker, and Wido G. M. Oerlemans. 2015. Challenge versus hindrance job demands and well-being: A diary study on the moderating role of job resources. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 88: 702–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Tomas, Adrian Furnham, and Grace Davis. 2003. A cross-cultural comparison of the money ethic, the protestant work ethic, and job satisfaction: Taiwan, the USA, and the UK. International Journal of Organization Theory and Behavior 6: 175–94. [Google Scholar]

- Thanigaivel, R. Krishnan, S. Ann Liew, and Vui-Yee Koon. 2017. The effect of Human Resource Management (HRM) practices in service-oriented Organizational Citizenship Behaviour (OCB): Case of telecommunications and internet service providers in Malaysia. Asian Social Science 13: 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, Soo Min, Frederick P. Morgeson, and Michael A. Campion. 2008. Human resource configurations: Investigating fit with the organizational context. Journal of Applied Psychology 93: 864–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torlak, N. Gökhan, Cemil Kuzey, Muhamment Sait Dinç, and Taylan Budur. 2021. Links connecting nurses’ planned behavior, burnout, job satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health 36: 77–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbini, Flavio, Chirumbolo Antonio, and Callea Antonio. 2020. Promoting individual and organizational OCBs: The mediating role of work engagement. Behavioral Sciences 10: 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ness, Raymond K., Kimberly Melinsky, Chery L. Buff, and Charles F. Seifert. 2010. Work ethic: Do new employees mean new work values? Journal of Managerial Issues 22: 10–34. [Google Scholar]

- Villajos, Esther, Nuria Tordera, José M. Peiró, and Marc van Veldhoven. 2019. Refinement and validation of a comprehensive scale for measuring HR practices aimed at performance-enhancement and employee-support. European Management Journal 37: 387–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, Max. 1930. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Max. 1958. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Translated by Talcott Parsons. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Larry J., and Stella E. Anderson. 1991. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. Journal of Management 17: 601–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zúñiga, Diana Carolina, David Aguado Garcia, Jesus Rodriguez Barroso, and Jesus Maria De Miguel Calvo. 2019. Work Ethic: Analysis of differences between four generational cohorts. Anales de Psicología Annals of Psychology 35: 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).