Abstract

The aim of this paper is to investigate the implications of Challenge-Based Learning programs on entrepreneurial skills, and on the mindset and intentions of university students, through a quantitative approach. Resorting to an original database, we analyzed the pre- and post-levels of entrepreneurial skills, mindset and intention of 127 students who attended a Challenge-Based Learning program. Results show a positive and significant effect of Challenge-Based Learning programs on the entrepreneurial mindset and skills—that is, financial literacy, creativity, and planning—of the students.

1. Introduction

Apart from education and teaching, universities have expanded their roles, since the end of the 20th century, with the introduction of the “Third Mission”, which was devised to contribute to cultural, social, and economic development through knowledge and technology transfer activities (Etzkowitz et al. 2000; Ricci et al. 2019; Colombelli et al. 2021a). On parallel ground, the European Commission has also recognized entrepreneurship as one of the eight key competences for citizens as a whole to promote personal development and social development, to ease entrance into the job market, and to create new ventures or scale existing ones (Bacigalupo et al. 2016). The European Commission, through the ENTRECOMP framework, is advocating more entrepreneurship education at all levels of education, to fill the population with the skill to “turn ideas into actions, ideas that generate value for someone other than for oneself.” In this framework, universities have implemented a broad range of entrepreneurial activities, such as entrepreneurship education (EE), support for the creation and growth of new ventures and intrapreneurship in existing organizations (Baruah and Ward 2014; Ricci et al. 2019). Entrepreneurship education has thus become an important activity from the perspective of professors, researchers, and university managers (Kuratko 2005) and a dramatic increase in the number of curricular and co-curricular offerings in entrepreneurship has been observed across the globe (European Commission 2008; Kuratko 2005; Morris et al. 2013).

Given its increasing importance, EE has more and more become the objective of academic research (Barr et al. 2009; Duval-Couetil et al. 2021). Within the stream of the literature on EE, an increasing number of works have been devoted to the identification and definition of different teaching methodologies, to learning approaches and to the analysis of their effectiveness (Dickson et al. 2008; Matlay 2008; Oosterbeek et al. 2010). The results have shown that EE may improve the entrepreneurial skills, mindset, and the career ambitions of students (Sánchez 2011; Cui et al. 2021). Moreover, experiential methodologies have proved to be particularly effective in the entrepreneurship domain (Rasmussen and Sørheim 2006). Among such methodologies, Challenge-Based Learning approaches have taken on momentum.

Challenge-Based Learning is a learning methodology in which students learn in a real context, and deal with challenges and real problems proposed by them or by existing firms (Chanin et al. 2018). Despite the increasing diffusion of the Challenge-Based Learning approach, evidence on its effectiveness is still limited (Johnson et al. 2009; Martinez and Crusat 2020; Palma-Mendoza et al. 2019; Vignoli et al. 2021), particularly in the Entrepreneurship Education field. Moreover, the available evidence is mainly descriptive and has been obtained using qualitative approaches (Martinez and Crusat 2017).

The present paper aims to empirically assess the effectiveness of Challenge-Based Learning programs in improving the entrepreneurial mindset, skills, and intentions of students. The empirical analysis is based on an original dataset of questionnaires filled in by 127 students who took part in a Challenge-Based Program proposed by the Politecnico di Torino, a technical university in Italy.

The remaining part of the paper is structured as follows. The theoretical background is discussed in Section 2. Section 3 describes the challenge-based program in entrepreneurship under scrutiny and the adopted methodology. Finally, the results and implications are discussed in Section 4 and Section 5.

2. Theoretical Background

The Challenge-Based Learning approach is an experiential learning methodology that allows students to learn by dealing with real challenges, such as founding a startup or solving real problems proposed by existing firms, while being supported by professors and/or external stakeholders. The specificity of this methodology is that students can apply the knowledge and competencies gained during their university career in a real context—unlike such methodologies as Problem-Based Learning or Project-Based Learning (Membrillo-Hernández et al. 2019)—and develop new skills, mindsets, and career aspirations thanks to these experiences.

So far, the objective of the academic research on Challenge-Based Learning approaches has been twofold. First, previous studies on Challenge-Based Learning have focused on how to design these kinds of programs and have identified best practices in different domains (Conde et al. 2019; Membrillo-Hernández and García-García 2020). Second, a still limited strand of literature has recently been devoted to understanding the effects of Challenge-Based programs on the participants (Johnson et al. 2009; Palma-Mendoza et al. 2019; Putri et al. 2020)

As far as the design of Challenge-Based programs is concerned, scholars and practitioners agree that Challenge-Based Learning programs should follow a framework composed of three stages: Engage; Investigate; Act (Apple Inc. 2012; Nascimento et al. 2019). The Engage stage requires participants to start with an idea, usually the main topic of the challenge, and try to figure out possible ways of realizing such an idea. At the end of the Engage stage, participants move to the Investigate stage, in which they are asked to frame the proposed solutions to tasks, draw up an implementation journey and understand what is needed to implement the solution. In the last stage, the Act stage, the participants start to implement the solution and to verify whether the solution is suitable to address the challenge or whether it needs to be revised. During these stages, the participants should be tutored by educators and other stakeholders, who guide them through the process of generation and implementation of the solution.

As for the effect of Challenge-Based programs on participants, the literature has shown that Challenge-Based Learning improves the soft skills, entrepreneurial intention and university performance of the participants (Johnson et al. 2009; Palma-Mendoza et al. 2019; Martinez and Crusat 2020; Colombelli et al. 2021b).

Johnson et al. (2009) investigated the effects of Challenge-Based Learning approaches on a sample of 312 high school students from six U.S. high schools. The students involved in the study were asked to work for some months on different real and global problems—such as, for example, the Sustainability of Food—in order to propose a solution that could then be implemented in their schools. At the end of the project, the students reported that they had improved such soft skills as critical thinking, creativity and problem-solving. Although the study showed a positive impact of the program on students’ skills, the evidence was built on self-reported information and did not allow the authors to verify whether the students’ skills had improved with respect to the pre-challenge levels.

In another study, Palma-Mendoza et al. (2019) analyzed the effectiveness of the I-semester program led by Tecnologico de Monterrey. The paper revealed a clear positive effect of the challenge-based approach on the students who participated in the program, but this effect was limited to the performance achieved in the related subjects and communication skills. Moreover, interesting evidence on the effect of the Challenge-Based Learning approach on the mindset and entrepreneurial intention of university students has been provided by Martinez and Crusat (2020). By focusing on the Innovation Journey Challenge-Based program, in which 20 teams of mechanical and electrical engineering students worked on innovative solutions to real problems proposed by municipalities, startups and firms, the paper shows that the program positively affected the participants’ propensity to become entrepreneurs.

Finally, Colombelli et al. (Colombelli et al. 2021b) have shown how Challenge-Based Programs could also improve the university performances of the academics who take part in them. The paper shows, through quantitative analysis, how PhD students who took part in a Challenge-Based Program are more likely to publish more and have a higher h-index than a counterfactual sample of PhD students who only differed in their lack of participation in the program. Moreover, they have also shown, using qualitative evidence, that these higher performances could be due to cross-fertilization with the MBA students who took part in the program together with the PhD students.

On the basis of these results, the Challenge-Based Learning methodology seems to improve the soft skills, performance and entrepreneurial intention and mindset of the participants. However, previous studies have mainly focused on generic skills and other measures of performance of the participants, such as university grades, but have neglected the possible effects on entrepreneurial skills. Moreover, the evidence on entrepreneurial intention and mindset was obtained using qualitative methodologies, which did not allow the extent to which students’ entrepreneurial skills had improved to be measured after the program. This paper therefore aims to quantitively assess whether Challenge-Based Learning methodologies improve the entrepreneurial skills, mindsets, and intentions of students.

3. Methodology

3.1. The Program

The challenge-based program analyzed in the paper, namely the Challenge@Polito initiative, is carried out by CLICK—Connection Lab and Innovation Kitchen—Laboratory of the Politecnico di Torino. This experimental teaching laboratory started in September 2017 and was conceived as an essential part of the university’s strategy to foster innovative education and an entrepreneurial culture.

After an initial settling-down period, in January 2019, CLIK organized the first Challenges (later re-named Challenge by Firms), while the first two “Challenge by Students” programs were added later on in September 2020.

The two types of Challenge, “_by Firms” and “_by Students”, are innovative training courses offered to students which are based on real challenges that are either introduced by an industrial partner (by firms) or identified with reference to the most up-to date “hot topics” in technology and innovation (by students). In both cases, a class of up to 30 Master’s Degree students, grouped into multidisciplinary teams made up of students with different backgrounds, look for new solutions to solve the proposed challenges. The Challenges last a semester, i.e., 14 weeks, and take place over two defined teaching periods, October/January and March/June, of each academic year.

The students are divided into teams of 5–6 people and work in a co-creation environment to find tech-based solutions to tackle the pre-set challenge by developing prototypes or demonstrators of the most promising ideas. Professors and mentors, from both technical and business backgrounds, support the Teams by guiding the students with hands-on suggestions to manage the many bottlenecks they have to face throughout the course. Moreover, multidisciplinary workshops are also organized during the challenges to provide educational content.

The main difference between these two types of challenge is:

- Challenge by Firms: a company or another external organization proposes a challenge to tackle a real problem they are facing or they believe will be faced in the relevant technological field in the near future. This kind of challenge aims to endow students with entrepreneurial skills and a mindset that can also be exploited in an organizational context.

- Challenge by Students: the Board members of CLIK identify macro-topics (e.g., climate change, circular economy, artificial intelligence) and the student teams work on developing business ideas they themselves propose within the identified macro-topic.

The strategic goals pursued by the university through the introduction of this program are related to the strengthening of the performance of the Third Mission of the university, with both direct and indirect outcomes being expected. Such challenges aim to stimulate:

- Directly: increasing the entrepreneurial culture and the entrepreneurially related soft skills of the students;

- Indirectly: the flourishing of the innovation ecosystem by fostering the hiring of creative talents within the existing companies, by supporting the creation of new start-ups and, in the long term, creating a new generation of academics with unprecedented sensitivity toward the application and transfer of their research in an economic environment, also paying attention to the social impact of their activities (Sansone et al. 2020).

Moreover, this challenge-based program has a specific objective related to two targets: students’ education and innovation, with special focus on impacting the local ecosystem.

The aims concerning students are:

- -

- To equip students with soft skills: problem-solving, lateral thinking, team working, project management and team management;

- -

- To promote a “Learning by doing” approach

- -

- To promote an entrepreneurial culture and behaviour;

- -

- To develop soft-skills;

- -

- To promote entrepreneurship;

The objectives concerning the impact on the ecosystem are:

- -

- To bridge the gap between universities and companies/ecosystem;

- -

- To sustain local economic development;

- -

- To support local SMEs;

- -

- To support the creation of innovative Start-ups

3.2. Sample

This study was carried out on a sample composed of former participants in a challenge-based program. The analyzed period was from January 2019 to January 2021, a period that included 11 challenges which involved approximately 300 students. The sample was composed of 127 students who filled in a questionnaire administered before and after participation in the challenge-based program.

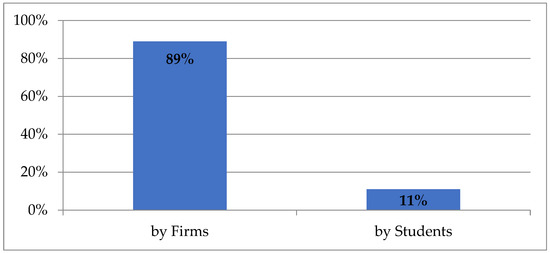

The sample was mainly composed of students who took part in “by Firms” challenges. Figure 1 shows that 89% of the students participated in “by Firms” challenges, while only 11% took part in a “by Students” challenge. Figure 2 shows the sample distribution by gender and reveals a prevalence of male students: males represent 66% of the sample and females 34%. The challenges were proposed to all the students at the university, thus to students belonging to three different fields of study: engineering, architecture, and design. The distribution of students in these three fields (Figure 3) is skewed toward the engineering area (91%), while the other two areas only account for 9% of the sample. Finally, Figure 4 shows the distribution of the students by nationality: 78% are Italian, against 22% of other nationalities.

Figure 1.

Distribution of challenges by type (%).

Figure 2.

Distribution of students by gender (%).

Figure 3.

Distribution of students by faculty (%).

Figure 4.

Distribution of students by nationality (%).

3.3. Description of Variables and Analysis

The data collection was based on a questionnaire filled in by 127 students to assess their entrepreneurial characteristics.

The entrepreneurial characteristics were measured through scales validated by Moberg et al. (2014). In order to build their indicators and subsequently design a survey, Moberg et al. (2014) referred to the framework developed by Heinonen and Poikkijoki (2006). This framework, which is recognized at the EU level by the Directorate-General for Enterprise and Industry (DG Enterprise and Industry), illustrates the dimensions that educational initiatives should focus on to develop enterprising individuals, such as students’ mindsets, attitudes, and career aspirations.

For the aim of this study, the considered variables were grouped into the following three domains (Table 1):

Table 1.

Variables, and their respective domains, used to measure students’ entrepreneurial characteristics.

- Mindset: The first domain is aimed at measuring the entrepreneurial mindset of students. This variable explains the respondent’s sense of initiative and attitude toward challenges.

- Entrepreneurial skills: The second domain variables included are creativity, planning, financial literacy, and managing ambiguity.

- Connectedness to the labor market: The third domain focuses on the importance for students of connecting the knowledge and the skills acquired to their future career. This is measured through entrepreneurial intention, i.e., the intention to start a business in the future.

The variables were measured on the basis of the results of a questionnaire administered to the students attending the Challenge-Based program. The questionnaire was administered before and after the challenge to assess any possible variations in the entrepreneurial characteristics of the students after attending the program.

Each entrepreneurial characteristic was measured using a specific set of items based on a seven-point Likert scale. After collecting information from the pre- and post-challenge questionnaires, the average value of each entrepreneurial characteristic was calculated as the average value of the corresponding items. The variables were collected using perceptual measures. A limitation of this approach is that perceptions often differ from reality, and self-reported measures could be affected by statistical problems, such as common method variance (CMV) and response trends. To preempt such concerns, perceptual measures are usually validated through econometric tests and factor analyses, which have demonstrated satisfactory reliability. We thus followed such an approach in the present work.

First, the questions presented in the survey were a combination of validated constructs developed or adapted by Moberg et al. (2014). These measurement tools were developed in a step-by-step process that included pre-studies and pilot testing. This increased the precision, validity and reliability of the measurement tools.

A confirmatory factor analysis was then performed to verify the validity of the scales adopted for the collection of the pre- and post-challenge data (Gupta and Somers 1992). Moreover, Cronbach’s alpha was used to assess the internal consistency of the constructs. Table 2 and Table 3 show the factor loadings and Cronbach’s alpha values obtained from the analysis of the pre- and post-challenge data.

Table 2.

Factor loadings and Cronbach’s alpha values obtained from the factor analysis conducted on the pre-challenge data.

Table 3.

Factor loadings and Cronbach’s alpha values obtained from the factor analysis conducted on the post-challenge data.

The results from the confirmatory analysis of the pre-challenge survey are shown in Table 1. The factor loadings are all greater than 0.50, thereby showing a good consistency of the constructs (Fullerton and McWatters 2001). Consequently, the corresponding items have a marked influence on the individual factors. Furthermore, the analyses that were carried out show greater Cronbach’s alpha values than 0.84 for all the variables (Table 1), except for the entrepreneurial mindset, which, in line with the factor loadings, instead presents a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.69. Thus, Cronbach’s alpha values confirm the internal consistency of the variables built on the data from the pre-challenge questionnaire (Nunnally 1978).

Table 2 shows the values of the factor loadings and Cronbach’s alpha obtained from the analysis of the data collected after the conclusion of the challenges. The factor loadings are always greater than 0.6, thus demonstrating, again in this case, good consistency of the items. The internal consistency is confirmed by Cronbach’s alpha values (Table 2). In fact, Cronbach’s alpha values are all higher than 0.85, except for the entrepreneurial mindset, which shows a value of 0.69.

4. Results

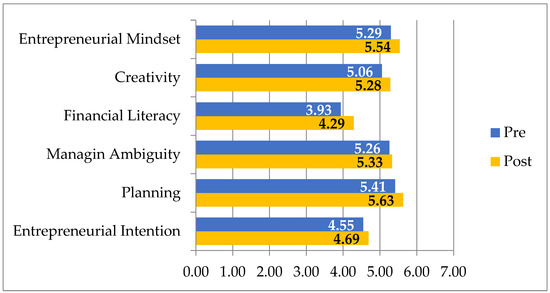

Descriptive statistics of both the pre- and post-entrepreneurial characteristics are shown in Figure 5. The entrepreneurial mindset of the sample increased from a pre-challenge value of 5.29 to 5.54 after the program. A similar growth also occurred for creativity and planning, which both increased by 0.22 points. As far as financial literacy is concerned, participation in the challenge led to a greater increase than for the previous variables. As for Managing Ambiguity and Entrepreneurial Intention, these variables both had a positive but smaller increase than the other variables. Accordingly, it seems that the challenge-based program had a positive effect on the entrepreneurial characteristics of the whole sample.

Figure 5.

Average values of entrepreneurial characteristics, pre- and post-challenge.

To confirm these results and verify the positive effect of the challenge-based program, t-tests were performed on the students’ entrepreneurial characteristics. T-test is an appropriate analysis to compare the mean of a variable among two or more groups (Fay and Proschan 2010). Building on this, we use this approach to assess possible differences in the means of the selected variables between two groups, the pre-challenge group and the post-challenge one. Moreover, this analysis provides reliable results in relation to the size of our sample (Stock and Watson 2012). The results are discussed using a significance level of 5% and are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Output t-test.

The results show that the difference between the post- and pre-challenge values of the entrepreneurial mindset is statistically significant and positive.

Participation in the challenge-based program increased the entrepreneurial mindset of the students who took part in it. As for entrepreneurial skills, it is possible to observe that the difference between the post- and pre-challenge is positive for all the variables, and this difference is statistically significant for creativity, financial literacy and planning. Finally, entrepreneurial intention also reveals a positive difference between the post- and pre-challenge results, although it is not statistically significant.

In short, our analysis shows that challenge-based programs positively affect the entrepreneurial mindset and skills, such as creativity, financial literacy and planning, of the students.

5. Conclusions

This paper shows the results of a study that was conducted to assess the effectiveness of challenge-based programs on the entrepreneurial skills, mindset and intentions of students. It is based on the quantitative analysis of questionnaire data collected from master’s degree students involved in the Challenge@Polito initiative, set-up by the Politecnico di Torino, in Italy. The study involved approximately 300 students, and 127 of them answered questionnaires administered before and after participation in the challenge-based program. The obtained results revealed that the program positively and significantly affected the entrepreneurial mindset and skills, such as creativity, financial literacy and planning, of the students who took part. The empirical evidence also shows an increase in the students’ entrepreneurial intention, although the effect is not statistically significant for this first set of data.

This work contributes to the literature in many respects. On the one hand, we provide further evidence of the effectiveness of entrepreneurial courses on participants’ entrepreneurial traits (Sánchez 2011; Cui et al. 2021). We specifically contribute to the literature regarding experiential learning, a setting that is gaining more and more attention in entrepreneurial courses (Pittaway and Cope 2007; Kassean et al. 2015; Colombelli et al. 2021c). On the other hand, the paper contributes to the increasing, but still limited, stream of literature on Challenge-Based Learning approaches and sheds first light on the effectiveness of challenge-based programs. First, we overcome several limitations of previous work on the challenge-based learning approach (Johnson et al. 2009; Palma-Mendoza et al. 2019). While previous works have mainly adopted qualitative methodologies (Martinez and Crusat 2020), we assess the effectiveness of challenge-based programs by adopting a quantitative approach and compare the results of pre-program and post-program data. Second, we analyze the effectiveness of the challenge-based approach in the entrepreneurship education context, which has been almost neglected by the previous literature.

Moreover, while previous works mainly focus on the university performance of attendees, we analyze how challenge-based programs might enhance participants’ entrepreneurial traits (Palma-Mendoza et al. 2019).

The paper also brings important implications for universities and policy-makers. As far as universities are concerned, this work provides several interesting suggestions. External companies mainly decide to join these initiatives to meet possible future workers. Nevertheless, they also build relationships with professors, mentors (young researchers) and the Technology Transfer office, thus setting the ground for future collaborations, also as a follow up of some of the student’s ideas. Such initiatives therefore represent an excellent occasion for, and have a direct impact on, the Third Mission of the University. Using Politecnico di Torino as an example, challenge-based programs also represent a win–win activity for all the actors involved: students, companies and the Politecnico di Torino. As regards the Challenge@PoliTo_by Students, despite the very small number of editions performed to date (only three), a start-up company has been funded, after having raised capital from private investors. Empirically, these data show that the impact of these activities is extremely relevant and they contribute significantly to the achievement of the university’s strategic goals, to the point that the university governance board decided to include the Challange@Polito in institutional master plans, to give credits to the students involved in the challenge and to increase the number of possible enrollments, thus taking a significant step towards a much acclaimed innovation in education which is often hard to achieve in practice, due to the many administrative burdens and obstacles public universities have to face.

As to the policy implications, this work suggests that challenge-based programs can ease the diffusion of entrepreneurial culture. Policymakers aiming at diffusing this culture should thus support the development of a challenge-based program in the entrepreneurship education domain.

This paper is not without limitations. The study addressed student attitudes and intentions before and after a Challenge, but not the actual behavior of the students in the periods following their participation in the Challenge. Kolvereid (1996) suggests that longitudinal studies that follow subjects for years after graduation are the only way to accurately prove the intention–behavior link. In future research on entrepreneurial education, the effect of Challenge-based learning programs could be tested longitudinally, by investigating and analyzing the eventual creation of ventures.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, A.C., S.L., A.P., O.A.M.P. and F.S.; writing—review and editing, A.C., S.L., A.P., O.A.M.P. and F.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Apple Inc. 2012. Challenge Based Learning: A Classroom Guide. Available online: https://www.challengebasedlearning.org/public/toolkit_resource/02/0e/0df4_af4e.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- Bacigalupo, Margherita, Panagiotis Kampylis, Yves Punie, and Godelieve Van den Brande. 2016. EntreComp: The Entrepreneurship Competence Framework. Luxembourg: Publication Office of the European Union, EUR 27939 EN. [Google Scholar]

- Barr, Steve, Ted Baker, Stephen Markham, and Angus L. Kingon. 2009. Bridging the Valley of Death: Lessons Learned from 14 Years of Commercialization of Technology Education. Academy of Management Learning and Education 3: 370–88. [Google Scholar]

- Baruah, Bidyut, and Anthony Ward. 2014. Enhancing Intrapreneurial Skills of Students through Entrepreneurship Education. Paper presented at the ITHET 2014—13th International Conference on Information Technology Based Higher Education and Training, York, UK, September 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Chanin, Rafael, Alan R. Santos, Nicolas Nascimento, Afonso Sales, Leandro Pompermaier, and Rafael Prikladnicki. 2018. Integrating Challenge Based Learning into a Smart Learning Environment: Findings from a Mobile Application Development Course. Paper presented at the International Conference on Software Engineering and Knowledge Engineering, SEKE, San Francisco, CA, USA, July 1–3; pp. 704–6. [Google Scholar]

- Colombelli, Alessandra, Antonio De Marco, Emilio Paolucci, Riccardo Ricci, and Giuseppe Scellato. 2021a. University technology transfer and the evolution of regional specialization: The case of Turin. The Journal of Technology Transfer 46: 933–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombelli, Alessandra, Andrea Panelli, and Emilio Paolucci. 2021b. The implications of entrepreneurship education on the careers of PhDs: Evidence from the challenge-based learning approach. CERN IdeaSquare Journal of Experimental Innovation 5: 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Colombelli, Alessandra, Andrea Panelli, and Francesco Serraino. 2021c. A Learning-by-Doing Approach to Entrepreneurship Education to Develop the Entrepreneurial Characteristics of University Students. Administrative Science, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Conde, Miguel Á, Camino Fernández, Jonny Alves, María-João Ramos, Susana Celis-Tena, José Gonçalves, José Lima, Daniela Reimann, Ilkka Jormanainen, and Francisco J. García Palvo ẽ. 2019. RoboSTEAM—A Challenge Based Learning Approach for Integrating STEAM and Develop Computational Thinking. Paper presented at the PervasiveHealth: Pervasive Computing Technologies for Healthcare, Trento, Italy, May 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Jun, Junhua Sun, and Robin Bell. 2021. The Impact of Entrepreneurship Education on the Entrepreneurial Mindset of College Students in China: The Mediating Role of Inspiration and the Role of Educational Attributes. International Journal of Management Education 19: 100296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, Pat H., George. T. Solomon, and K. Mark Weaver. 2008. Entrepreneurial Selection and Success: Does Education Matter? Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 15: 239–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval-Couetil, Nathalie, Michael Ladisch, and Soohyun Yi. 2021. Addressing academic researcher priorities through science and technology entrepreneurship education. The Journal of Technology Transfer 1: 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzkowitz, Henry, Andrew Webster, Christiane Gebhardt, and Branca Regina Cantisano Terra. 2000. The future of the university and the university of the future: Evolution of ivory tower to entrepreneurial paradigm. Research Policy 29: 313–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2008. Best Procedure Project: Entrepreneurship in Higher Education, Especially in Non-Business Studies. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/content/final-report-expert-group-entrepreneurship-higher-education-especially-within-non-business-0_en (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- Fay, Michael P., and Michael A. Proschan. 2010. Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney or T-test? on assumptions for hypothesis tests and multiple interpretations of decision rules. Statistics Surveys 4: 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fullerton, Rosemary R., and Cheryl S. McWatters. 2001. Production performance benefits from JIT implementation. Journal of Operations Management 19: 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Yash P., and Toni M. Somers. 1992. The Measurement of Manufacturing Flexibility. European Journal of Operational Research 60: 166–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinonen, Jarna, and Sari-Anne Poikkijoki. 2006. An Entrepreneurial-Directed Approach to Entrepreneurship Education: Mission Impossible? Journal of Management Development 25: 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Laurence F., Rachel S. Smith, J. Troy Smythe, and Rachel K. Varon. 2009. Challenge-Based Learning: An Approach for Our Time. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED505102.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Kassean, Hemant, Jeff Vanevenhoven, Eric Liguori, and Doan E. Winkel. 2015. Entrepreneurship education: A need for reflection, real-world experience and action. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 21: 690–708. [Google Scholar]

- Kolvereid, Lars. 1996. Organisational employment versus self employment: Reasons for career choice intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 20: 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuratko, Donald F. 2005. The Emergence of Entrepreneurship Education: Development, Trends, and Challenges. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice 29: 577–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, I. Mar, and Xavier Crusat. 2020. How Challenge Based Learning Enables Entrepreneurship. Paper presented at the IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference, EDUCON, Porto, Portugal, April 27–30; pp. 210–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, Mar, and Xavier Crusat. 2017. Work in progress: The innovation journey: A challenge-based learning methodology that introduces innovation and entrepreneurship in engineering through competition and real-life challenges. Paper presented at the 2017 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Athens, Greek, April 6–28; pp. 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Matlay, Harry. 2008. The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial outcomes. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 15: 382–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Membrillo-Hernández, Jorge, and Rebeca García-García. 2020. Challenge-Based Learning (CBL) in Engineering: Which evaluation instruments are best suited to evaluate CBL experiences? Paper presented at the IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Porto, Portugal, April 27–30; pp. 885–93. [Google Scholar]

- Membrillo-Hernández, Jorge, Miguel J. Ramírez-Cadena, Mariajulia Martínez-Acosta, Enrique Cruz-Gómez, Enrique Muñoz-Díaz, and Hugo Elizalde. 2019. Challenge Based Learning: The Importance of World-Leading Companies as Training Partners. International Journal on Interactive Design and Manufacturing 13: 1103–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moberg, Kåre, Lene Vestergaard, Alain Fayolle, Dana Redford, Thomas Cooney, Slavica Singer, Klaus Sailer, and Diana Filip. 2014. How to Assess and Evaluate the Influence of Entrepreneurship Education. ASTEE project. Available online: https://www.sce.de/fileadmin/user_upload/AllgemeineDateien/06_Forschen/Forschungsprojekte/E_ship_Education/ASTEE/ASTEE_Report_2014.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- Morris, Michael H., Justin W. Webb, Jun Fu, and Sujata Singhal. 2013. A Competency-Based Perspective on Entrepreneurship Education: Conceptual and Empirical Insights. Journal of Small Business Management 51: 352–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, Nicolas, Afonso Sales, Alan R. Santos, and Rafael Chanin. 2019. An Investigation of Influencing Factors When Teaching on Active Learning Environments. Paper presented at the Pervasive Health: Pervasive Computing Technologies for Healthcare, Trento, Italy, May 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, Jum. 1978. Psychometric Theory. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Oosterbeek, Hessel, Mirjam Van Praag, and Auke Ijsselstein. 2010. The Impact of Entrepreneurship Education on Entrepreneurship Skills and Motivation. European Economic Review 54: 442–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma-Mendoza, Jaime A., Teresa Cotera Rivera, Ivan Andrés Arana Solares, Sandra Viscarra Campos, and Ernesto Pacheco Velazquez. 2019. Development of Competences in Industrial Engineering Students Inmersed in SME’s through Challenge Based Learning. Paper presented at the TALE 2019—2019 IEEE International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Education, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, December 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Pittaway, Luke, and Jason Cope. 2007. Simulating Entrepreneurial Learning: Assessing the Utility of Experiential Learning Designs. Management Learning 38: 211–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, Noviana, Dadi Rusdiana, and Irma Rama Suwarma. 2020. Enhanching Physics Students’ Creative Thinking Skills Using CBL Model Implemented in STEM in Vocational School. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series. Bristol: IOP Publishing, vol. 1521. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, Einar A., and Roger Sørheim. 2006. Action-Based Entrepreneurship Education. Technovation 26: 185–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, Riccardo, Alessandra Colombelli, and Emilio Paolucci. 2019. Entrepreneurial Activities and Models of Advanced European Science and Technology Universities. Management Decision 57: 3447–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, Giuliano, Pietro Andreotti, Alessandra Colombelli, and Paolo Landoni. 2020. Are social incubators different from other incubators? Evidence from Italy. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 158: 120132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, José C. 2011. University Training for Entrepreneurial Competencies: Its Impact on Intention of Venture Creation. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 7: 239–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, James. H., and Mark. W. Watson. 2012. Introduction to econometrics. New York: Pearson, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Vignoli, Matteo, Bernardo Balboni, Andreea Cotoranu, Clio Dosi, Noemi Glisoni, Kirstin Kohler, Giuseppe Mincolelli, Saku Mäkinen, Markus Nordberg, and Christine Thong. 2021. Inspiring the future change-makers: Reflections and ways forward from the Challenge-Based Innovation experiment. CERN IdeaSquare Journal of Experimental Innovation 5: 1–4. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).