Abstract

Governance researchers have repeatedly discussed how to make public governance more accountable given the relatively ‘thin’ accountability of representative government. Recent decades have seen the growth of new, compensatory forms of accountability. However, these measures do not seem have satisfied the demands for strengthening public sector accountability. Drawing on the concept of social accountability, this article challenges common wisdom in arguing that collaborative governance may enhance public governance accountability, although it also raises new accountability problems that must be tackled. The article develops a heuristic framework for empirical studies of accountability, which improves the impact of collaborative forms of governance.

1. Introduction

Heeding the call for positive public administration research (Compton et al. 2021; Douglas et al. 2021), this prospective review article aims to explore how and under which conditions collaborative governance may help to secure accountable government by facilitating high-quality, dialogue-based exchanges between public authorities and societal stakeholders, including citizens, local neighborhoods, civic organisations etc. (Dillard and Vinnari 2019)

Exploring how collaborative governance may improve public sector accountability is crucial since the traditional institutions of representative democracy provide relatively thin accountability (Schillemans 2008; Warren 2014). Public institutions have rules and procedures that secure some level of government transparency, and they offer opportunities for mass media and the general public to scrutinize what elected and non-elected public officials do and how they do it. Citizens have constitutional rights to vote in regular elections, where they can express their dissatisfaction with incumbent governments. Nevertheless, there are limited opportunities for public authorities to give thorough, non-technical and issue-specific accounts of public governance and for citizens to ask questions and evaluate such accounts in order to pass judgements and pose sanctions. Moreover, in representative democracy, voters are asked to make grand ‘synoptic’ judgments (Lindblom 1979) about how their elected representative is likely to act across a wide range of complex policy issues in the next four or five years. Occasionally, they use their vote to protest against particular decisions, but the voting procedure provides a poor means of political communication between voters and politicians. Governments seldom know exactly why they either won or lost an election (Fung 2015).

The relatively thin accountability accruing from the institutional mechanisms of representative government may have been enough to secure democratic legitimacy in times dominated by an allegiant political culture characterized by high levels of trust in the wisdom of government (Dalton and Welzel 2014). In today’s advanced representative democracies, however, the thin forms of accountability appear to be insufficient to satisfy an increasingly competent, critical and assertive citizenry that is nurtured by public education, a mediatized drama democracy and the rise of new social media (Dalton and Welzel 2014; Esser and Strömbäck 2014; Neblo et al. 2010; Norris 2011).

Over the last 40 years, this shift in political culture has placed governments under growing pressure to account for their governing. In response, they have introduced different supplementary accountability measures, including administrative, legal and political auditing (supreme auditing institutions), open government initiatives (e.g., ombudsmen, open access, whistle-blowers), performance management systems (league-tables, key performance indicators), independent monitoring agencies (think tanks, watchdogs) and different voice and exit options for public service users (user boards, free service choice) (Bovens and Wille 2020; Bovens et al. 2014b; Keane 2009; Pierre et al. 2018; Power 1997; Salamon 2002; Sørensen 1997). However, the new accountability measures have not reduced the demand for further efforts to strengthen public sector accountability (Bovens et al. 2014b; Lægreid 2014; Shkabatur 2012). In addition, the new accountability measures may not be delivering what is needed. There have been mounting criticisms of the new public auditing and monitoring systems for suppressing innovation, failing to address the big problems, stimulating window dressing, enhancing bureaucracy and imposing increasing costs on public organizations (Kells 2011). Finally, on a deeper theoretical level, the problem is that the supplementary accountability measures are based on a fundamental distrust, meaning that government agencies tend to become more guarded and self-protective, and thus less open to scrutiny.

Consequently, we suggest that the route to strengthening public sector accountability in advanced representative democracies is not to invent more of the current mechanisms for transparency, oversight and sanctioning (see Honig and Pritchett 2019). Surely, the public access to information about government performance and the possibility for citizens to evaluate, judge and sanction such performance through regular elections provides indispensable support for the answerability of government. However, if we want to ‘thicken’ public accountability by making it more precise and issue-specific, trust-based and founded on shared norms, values and obligations, we must enhance the interaction between the public sector and relevant social and economic actors. Enhanced interaction will enable government agencies to explain their governance outputs and public value outcomes to societal stakeholders and allow the latter to ask pertinent questions, effectively communicate critical opinions and ensure government responsiveness (see Dubnick 2003; Honig and Pritchett 2019). Hence, as we define it, thick accountability refers to a dialogical accountability relationship in which: (1) account givers have both capacity and opportunity to provide precise and adequate accounts about particular governance decisions and the mission-related results that are obtained; and (2) account holders have both skills and competences to critically assess and sanction these accounts vis-à-vis a broad set of norms, values and obligations. Performing these roles in thick accountability processes requires mutual trust, since account givers will not provide an honest account of things if they do not trust the account holders to make a fair judgement, which in turn depends on the account holder trusting that the account is complete (Hardin 2002).

The argument advanced in this paper is that collaborative governance in networks and partnerships can promote a new type of social accountability that helps to hold governments to account for their deeds (Bianchi et al. 2021; Fox 2015; Sørensen and Torfing 2020). Collaborative governance brings together public actors and private stakeholders in a shared effort to solve complex societal problems in a turbulent world and to create governance solutions and outcomes that have value to the public and in public values (Ansell and Gash 2008; Emerson et al. 2012). Ideally, collaborative interaction involves trust-based knowledge sharing, joint exploration of problems and solutions, compromises and agreements about joint action, critical scrutiny of the impact of new governance initiatives, and responsive discussions of problems and failures, and thus the need for future adjustments and revisions. The empowered participation of intensely affected actors helps to ensure that lay actors are heard in the design phase and able to scrutinize results. Procedures for deliberation based on reasoned debate and passionate argumentation tend to enhance the fairness of policy processes. Finally, joint scrutiny and mutual learning processes help to correct and improve public governance solutions. Hence, collaborative governance may strengthen public accountability while simultaneously enhancing input, throughput and output legitimacy. Empirical evidence shows that collaborative governance may lead to better governance solutions (Doberstein 2016), enhanced government accountability vis-à-vis stakeholders (Roberts 2002; Schillemans 2011) and more democratic legitimacy (2017). The conditions for collaborative governance to produce such desirable outcomes have been studied by Mattessich and Monsey (1992) and, more recently, in empirical case studies reported to the Collaborative Governance Data Bank (Douglas et al. 2020).

We realize that, in real life, collaborative governance often involves empowered sub-elites rather than ordinary citizens who frequently lack time, resources and motivation to participate (see Ghose 2005), although active inclusion management creating incentives, interdependencies and mutual trust may get them on board (Ansell et al. 2020). We suggest, however, that these sub-elites play a key role in connecting government and citizens and in enhancing public governance accountability (Etzioni-Halevy 1993; Esmark 2007). Hence, by participating in collaborative governance processes, sub-elites assist ordinary citizens in making measured and realistic assessments and judgements of the public accounts they gain access to. They may even have the capacity to put pressure on public authorities to improve both the quality of public accounts and the performance of public governance by mobilizing mass media and groups of affected citizens.

The crux of the argument is that collaborative governance processes based on the participation of competent, critical and engaged sub-elites can serve as ‘enabling environments’ (Fox 2015) for advancing public governance accountability in advanced representative democracies. Areas pertaining to national security or public contracting may provide notable exceptions, and active involvement of citizens in collaborative governance arrangements aiming to hold public decision-makers to account tends to be more frequent at the local level than the regional, national or transnational levels; here, sub-elites will have to act on their behalf.

Although collaborative governance holds a promise of enhancing public sector accountability, we should not forget that collaborative governance raises just as many accountability problems as it solves (Schillemans 2008). As widely recognized in governance research, collaborative governance arrangements are notoriously difficult to hold to account because they come with a certain degree of opaqueness, secrecy and informality (Klijn 2014). It can sometimes be difficult for external audiences to obtain the information required to scrutinize and pass judgement on process, outputs and outcomes, determining who is responsible for governance failure is particularly hard, and there is no clear way of sanctioning collaborative networks of more or less self-appointed actors; although naming and shaming the collaborative arena is an option (Damgaard and Lewis 2014; de Fine Licht and Naurin 2016; Klijn and Koppenjan 2014; Papadopoulos 2007; Sørensen and Torfing 2020). We must therefore find viable ways to enhance the accountability of collaborative governance processes; and once again, the concept of social accountability may be of value.

This article contributes to the scholarship on public accountability by developing a heuristic stages model showing how collaborative governance may enhance government accountability. The structure of the argument is as follows. First, we define public accountability and critically evaluate the ‘thin’ accountability provided by the institutions of representative government. Next, we provide a brief overview of the efforts to improve public governance accountability in recent decades and reflect on their limitations. We then show how collaborative governance may enhance social accountability, thereby contributing to the ‘thickening’ of public governance accountability in advanced liberal democracies. After considering and solving the accountability problems associated with collaborative governance by invoking the ideas inherent to social accountability, we present a heuristic framework for studying how collaborative forms of governance affect public accountability. We conclude by summarizing the key messages.

2. Public Governance Accountability in Representative Democracy

Accountability is one of the normative pillars of representative democracy because it allows citizens to control elected politicians and, through them, the public employees responsible for implementing public solutions (Behn 2001; Lührmann et al. 2020; Warren 2014). According to widely accepted global standards, a political system that fails to provide structures and procedures enabling citizens to critically assess what elected officials and public authorities are doing and to punish or reward them accordingly is not a democracy (Freedom House 2020; V-DEM Institute 2021). Accountable government is a democratic prerequisite.

There is some debate about what accountability entails more precisely. Drawing on the minimum definition in the introductory chapter of the Oxford Handbook of Public Accountability (Bovens et al. 2014a), the term refers to an actor who is answerable to another actor with a legitimate claim to demand information and explanation, pass judgement and impose sanctions. Public accountability then refers to an accountability relationship between those who govern and those who are governed within the public domain.

Although there is considerable variation between models of representative democracy, they all provide horizontal and vertical mechanisms for making public authorities answerable to each other and to the public (Lührmann et al. 2020). Building on De Montesquieu’s ([1748] 1989) call for a separation of powers, the horizontal accountability mechanisms take the form of checks and balances between relatively autonomous branches of government, such as the judiciary, executive and legislative powers (more recently including ombudsman institutions). Horizontal accountability assumes that an authoritative power holder must be controlled by another authoritative power in order to prevent the usurpation of power by a single power holder (Breuer and Leininger 2021; O’Donnell 1998; Schillemans 2008, 2011). The vertical accountability mechanisms come in the shape of formal rules and procedures that secure some level of transparency of political and administrative processes and outcomes pertaining to public policy, regulation and service delivery. A free public sphere with independent media provides citizens with information and opportunities to debate the process and outcomes of public governance and force politicians and other public actors to explain themselves. Moreover, administrative complaint systems grant citizens the right to challenge government decisions, and, perhaps most importantly, regular elections provide the means to penalize or reward government and opposition parties for the role they have played in governing society and the economy. The basic assumption behind these institutional arrangements is that accountability is a product of a principal–agency relationship wherein citizens delegate power to elected politicians and public managers, subsequently holding them accountable for the outputs and outcomes they produce and deliver (Gailmard 2014; Ingham 2019; Lührmann et al. 2020; Warren 2014). This assumption has roots in protective democracy that claims that elected government officials who are spending revenues accruing from taxation should be accountable to the citizens who are paying taxes (Christiano 2018; Held 2006; Joshi 2013).

Although the traditional accountability mechanisms in representative government do indeed promote public sector accountability, there are clear limitations. The horizontal accountability mechanisms might be quite effective, but they merely provide checks and balances between different public authorities and do not involve the general public. Vertical accountability mechanisms typically involve the general public, but tend to give citizens relatively few opportunities to scrutinize government action, pass judgements and sanction bad governance (Ashworth et al. 2017; de Benedictis-Kessner and Warshaw 2020; Warren 2014). Large parts of government live a secluded life protected by the secrecy acts and ‘securitization’ of public policy and governance that tend to limit access to information (White 2002; Wæver 1993). The public accounts accessible to citizens are often technical and the information that reaches citizens is filtered through elite-dominated media operating on the basis of particular news criteria. If the citizens are dissatisfied with the incumbent government, they can write letters to the editor or organize protests forcing the politicians to respond to public criticism. This response is often reduced to one-line soundbites in the media, however, which renders the explanation of complex issues difficult. If citizens remain dissatisfied with government policy, they can vote for an opposition party in the next election. The government may lose the election, but it is often unclear whether the voters disliked a particular policy, were tired of watching the same old faces, or thought that the opposition offered a better alternative. Hence, elections fail to communicate the voters’ reasons for voting how they do and leave it to political parties and their professional staff to interpret the election result based on focus group studies and media debates that are of varying quality. This reality led Joseph Schumpeter (1942) to claim that representative democracies do not give citizens the power to control the government, but merely allow them to elect their rulers. Many years later, Benjamin Barber (1984, p. 221) drew a similar conclusion when describing representative democracy as ‘thin’ in the sense that it positions citizens as disempowered spectators to elite rule. Citizens may vote in general elections, but in deciding which party to vote for they have to judge how elected representatives are likely to act across a wide range of complex policy issues, thus leaving limited scope for holding the incumbent government to account for a particular policy failure.

A key factor reducing the public accountability in representative democracies is the restrictions on the information that politicians and administrators may relay to the public. Public administrators and their political principals have an interest in hiding administrative inefficiencies and implementation problems, information containing personal data or pertaining to internal processes cannot be disclosed, and the retrieval of accessible information is often costly and requires the documentation of affectedness or prior and precise knowledge of the requested information (Candeub 2013; Graves and Katyal 2020; White 2002). Moreover, the administrative state has no tradition for documenting administrative governance outputs and public value outcomes. Horizontal accountability based on checks and balances between the legislative, executive and judiciary powers secures legal and fiscal control, but tends to remain an in-house activity, rarely involving those actors who are affected by bad governance.

Since the 1970s, the traditional accountability mechanisms supplied by the institutions of representative government have met growing critique for their inability to secure sufficient levels of public control with those in power (Behn 2001; Christensen and Lægreid 2015; Fatemi and Behmanesh 2012; Whiteley and Kölln 2019). Three strands of critique seem to point in the same direction, thus strengthening the demand for a more accountable government. First, neoliberal commentators have criticized the public sector for being ineffective and squandering taxpayer money (Lane 1997), and they called for the introduction of performance management systems to enhance public sector transparency, for example, by forcing public schools to publicize performance information. Second, mass media and civil society actors have challenged governments to provide more and better access to information about government operations (Grimes 2013; Jacobs and Schillemans 2016; Norris 2014; Sørensen 2020). Finally, the education revolution and anti-authoritarian revolt has empowered citizens in the Western world (King 1987), transforming the political culture from an allegiant to an assertive culture in which a growing number of critical and competent citizens are ready to confront the governing elites (Dalton and Welzel 2014; Dudley et al. 2015). The latter has been fueled by the new social media and growing mediatization of politics and political communication (Esser and Strömbäck 2014; Park 2013; Sørensen 2020). In sum, we have witnessed a growing demand for the introduction of new supplementary accountability mechanisms.

The new vertical forms of accountability include the introduction of elaborate performance management systems that measure and report key performance indicators and benchmark results through the construction of league tables that enhance transparency and facilitate public scrutiny (Power 1997). Performance information can be used by service users who are given new exit and voice options, allowing them to vote with their feet by choosing another service provider or be elected to a user board, where they can raise criticisms and complain about low and inadequate service standards are (Hirst 2000; Sørensen 1997; Warren 2011; Holbein and Hassell 2019). The new accountability mechanisms also include the formation of independent monitoring agencies that play a watchdog role, keeping an eye on what politicians and public agencies are doing and how they are performing (Keane 2009). A growing number of national and international NGOs are engaged in monitoring government action in the field of human rights protection, environmental issues and social inequality. The UN Sustainable Development Goals provides an agreed-upon standard for holding governments to account for their actions and comes with an array of targets and indicators. Finally, the new accountability mechanisms include Open Government initiatives (Attard et al. 2015; Clarke and Francoli 2014) that give critical and assertive citizens the right to access government documents and proceedings in order to allow for effective public oversight, create ombudsman institutions charged with representing the interests of the public by investigating and addressing complaints of mal-administration or a violation of rights, and introduce whistle-blower systems that enable public employees or third parties to disclose secrets and report illegal, unethical or inappropriate public action without punishment.

These supplementary accountability mechanisms have purported to make the public sector more transparent and citizens more informed, and they have provided new tools with which to sanction government agencies and public service institutions between elections. However, political scientists as well as public administration and governance scholars have begun doubting that more transparency, oversight and sanctioning tools will decisively advance government accountability, which is basically what the predominant principal–agent perspective on accountability seems to suggest. Some scholars argue that there is a considerable risk that such a strategy will neither strengthen the position of citizens and private stakeholders vis-à-vis public authorities nor enhance the capacity of the public sector to respond effectively to the voice of the people (Bovens and Wille 2020; Bovens et al. 2008; Christensen and Lægreid 2015; Power 1997). Citizens and stakeholders may drown in the pool of transparent government information and performance data and may not act on negative performance as the proponents of performance accountability propose (Holbein and Hassell 2019). At the same time, public, mediatized criticisms of alleged government failures may merely trigger a self-preserving blame-game that hardly provides any learning-based corrections (Hood 2010). Consequently, the search is on for a new perspective on accountability that, in sharp contrast to the principal–agent perspective, focuses on enhancing the quality of the accountability relationship between the public sector and the civic and socioeconomic actors in its societal environment.

2.1. Enhancing Public Governance Accountability through Social Accountability

The search for ways of enhancing public governance accountability and granting the involved actors what Bovens and Wille (2020) denote accountability power can find valuable inspiration in a social accountability perspective. Social accountability is an umbrella term for strategies aiming to improve public sector performance via the creation of productive and synergetic state–civil society interactions (Antlöv and Wetterberg 2021; Fox 2015; Hickey and King 2016; Joshi and Houtzager 2012; Schatz 2013). As such, a social accountability perspective claims that a thicker accountability relationship not only requires that the societal actors aiming to hold public decision-makers to account have the capacity and resources needed to do so; the public actors who are held to account must also be bolstered, so that they can provide accessible accounts of often complex decisions and respond to the issues and criticisms voiced by societal actors.

The idea is that accountability as a product of a mutually empowering relationship resonates well with recent developments in theories of collaborative governance, co-creation and integrative public leadership that tend to view the mobilization and empowerment of citizens and civil society actors as key means to empower elected governments and the public sector (Alford 2014; Ansell and Torfing 2021; Burns 2003; Crosby and Bryson 2010; Emerson and Nabatchi 2015; Nye 2008; Osborne 2010). While these strands of research are mainly interested in how state–society interactions can help to enhance public value production based on a ‘collaborative advantage’ (Huxham and Vangen 2013), they are much less concerned with strengthening public governance accountability; hence, the good prospect for a happy marriage between the new theories of collaborative governance and the social accountability concept.

Jonathan Fox (2015) argues that the key to promoting social accountability is to build an ‘enabling environment’. Such an environment spurs stakeholder participation and oversight in relation to specific policy issues, helps to diffuse information about public performance, and coordinates and integrates the critical assessments of local, regional and national civil society actors to add teeth to the citizens’ voices. It also provides favorable conditions for public authorities to explain their actions and results to relevant and affected actors and to engage with critical voices and build pro-accountability alliances that enhance the willingness to accommodate and learn from critical feedback on public regulation, governance and service provisions and support and defend reforms that strengthen cross-boundary collaboration (Fox 2015, p. 355). An enabling environment bolsters the skills and resources of public actors with respect to explaining themselves in encounters with competent, critical and assertive citizens and vested social and economic interests. For politicians, this implies mustering their courage and rhetorical ability to explain complex, dilemma-filled political decisions based on negotiations and compromise to the citizens and stakeholders. For public employees, it means strengthening their ability to communicate their professional motivations, concerns and considerations to lay actors. Finally, yet importantly, an enabling environment for social accountability enhances the capacity of citizens and stakeholders to make well-informed, realistic and measured assessments of what public authorities do and provide, thereby enhancing the ability of public agencies to use the feedback to improve performance. Social accountability provides a new type of dialogical accountability (Dillard and Vinnari 2019) as the critical judgement of the accountability forum is provided in a dialogue between the account-giver and the accountability forum. Sanctions do not involve the exercise of hard power such as political, legal or economic sanctions. Sanctions primarily rely on soft power such as public criticism problematizing the legitimacy of particular actions or the failure to take action. However, such a criticism may be quite effective in democratic societies or when they are taken up my particular branches of government capable of using hard power.

Some advocates tend to view social accountability as an alternative rather than a supplement to the accountability mechanisms of representative government (see Joshi and Houtzager 2012). This view is explained by the fact that the concept of social accountability developed as a strategy for enhancing public accountability in developing countries with limited horizontal and vertical accountability measures and large problems with corruption and election fraud (Feruglio and Nisbett 2018; Fox 2015). Our claim, however, is that while social accountability may provide an alternative failsafe in developing countries, it offers a much-needed supplement to enhance public governance accountability in developed Western democracies with elaborate systems of horizontal and vertical accountability, which, as shown above, suffer from different limitations. Hence, building an enabling environment that enhances the quality of the accountability-related exchanges between public and private actors appears to offer a promising route to making public governance accountability thicker and public governance more legitimate. What social accountability adds to the existing accountability mechanisms in representative democracy is the idea that accountability is improved if empowered public and civil society actors engage in an ongoing dialogue about outputs and outcomes in a particular policy area of great importance to both parties and use that dialogue to provide comprehensive, yet accessible accounts of activities and results, solicit well-informed and precise feedback from a broad range of actors with different backgrounds and perspectives, and learn from critical evaluations and constructive suggestions.

Indeed, positive synergies between social, horizontal and vertical accountability that secure quality exchanges in a context of transparency, oversight and effective sanctions appear to be particularly important in advanced liberal democracies in which the increasingly assertive citizens may not get what they want from government, voice their harsh criticisms in the echo chambers of social media, and perhaps end up supporting authoritarian populist parties and politicians who claim to side with the common man and wage war against the establishment (Bartlett et al. 2011; Mudde and Kaltwasser 2012). This is the reality in many ‘old’ liberal democracies that struggle to respond effectively and legitimately to complex and turbulent policy problems, such as climate change, immigration, pandemics, homelessness, drug abuse, poverty, unemployment and lifestyle-related illnesses under the watchful and critical eye of old and new media, well-organized stakeholders and assertive citizens (Sørensen 2020). Without the mutual understanding and accommodation that grows out of ongoing high-quality exchanges between public authorities and relevant and affected stakeholders, including users, citizens and civil society organizations, and preferably in a context of horizontal and vertical checks, balances and controls, a further decline in the trust in public authorities and perhaps even in the legitimacy of democratic political systems is likely.

2.2. Collaborative Governance as an Enabling Environment

Since the turn of the century, collaborative governance has gained increasing recognition among governance researchers and public decision-makers for its ability to promote the effectiveness, democratic legitimacy and innovative capacity of public governance (Agger et al. 2015; Agranoff and McGuire 2003; Crosby and Bryson 2005; Emerson et al. 2012; Stoker 2006; Sørensen and Torfing 2017). Collaborative governance refers to processes and structures that bring together relevant and affected public and private stakeholders from different levels, sectors and organizations in a shared effort to solve governance problems and produce public value (Ansell and Gash 2008; Emerson and Nabatchi 2015). In the early days, collaborative forms of governance were mainly perceived as a lender of last resort when governance based on public hierarchies and private markets had failed. Nowadays, they are increasingly seen as superior mechanisms for solving complex and turbulent governance problems and as necessary instruments when the power, authority and resources to govern are widely distributed across actors, sectors and levels (Ansell and Trondal 2018; Bryson et al. 2015; Torfing et al. 2012). At present, collaborative governance arrangements, such as networks and partnerships, are widely celebrated for their ability to stimulate mutual learning and innovation in public policy and service delivery, to strengthen the democratic legitimacy of public governance through inclusive and empowered participation, and to mobilize stakeholder resources to expand the reach of governance and get things done (Bommert 2010; Sirianni 2010; Torfing 2016). However, much less attention has been paid to the positive impact that collaborative governance may have on public governance accountability. Indeed, governance researchers have mainly discussed the negative impact of collaborative governance that stems from the many hands problem (Bovens et al. 2008); that is, the problem of knowing exactly who was involved in making a particular decision in a collaborative arena, and thus who to blame for governance failure. The neglect of the positive role that collaborative governance may have in boosting public governance accountability is surprising, since collaborative governance allows a broad range of societal actors to obtain first-hand knowledge of government affairs, debate problems and solutions with responsible public actors, carefully evaluate processes and outcomes, protest over unfair procedures and negative results, and bring critical issues to the attention of the media.

To compensate for this benign neglect, we propose that collaborative forms of governance have the potential to serve as an enabling environment for the promotion of social accountability and, thus, to thicken the otherwise thin public governance accountability in advanced liberal democracies. Collaborative governance not only brings together relevant and affected public and private stakeholders in a shared effort to govern society effectively, democratically and innovatively. It also constructs a site for a well-informed, critical and problem-focused scrutiny and assessment of public governance based on continuous interaction and deliberation involving relevant and affected actors with both an interest in holding public authorities to account and who have sufficient resources and media access to add teeth to their critical voices. Both public and private stakeholders are present in the collaborative governance arenas, and there is sufficient time and space for the public actors to explain themselves, present relevant material and to document results. For their part, the private actors can ask questions, demand further documentation, voice their opinion, debate solutions and results and, in retrospect, pass judgement on both process and outcomes.

Trust-building and deliberation between public and private actors engaged in collaborative governance may construct accountability alliances seeking to promote ongoing account-giving and scrutiny in order to enhance effective governance. Collaborative governance is thus likely to stimulate the development of a shared understanding of past, present and future governance solutions, including a critical inquiry into the actions and intentions of public as well as private actors contributing to public value production in the particular area. To illustrate, when a partnership of private businesses, trade unions and local public actors are brought together to find a way of including disabled people or traumatized refugees in the labor market, their efforts to find common ground will tend to involve critical reflection on the existing government policy and ongoing practices that may result in joint demand for explanations of the reason for upholding failing strategies and political support for innovative strategies that rectify past problems and overcome barriers to problem-solving. In the same vein, a network of politicians, administrators, NGOs and local citizens aiming to accelerate the implementation of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) will not only seek to influence future policies and actions. It will also engage in a critical assessment of how the government has hitherto attempted to implement the SDGs, what the problems are, and how they can be solved. The private stakeholders may voice criticisms of past and present undertakings and the government actors may respond constructively by making concessions and proposing new and better solutions; if not, the private stakeholders may draw public attention to critical issues by contacting mass media or using social media to flag problems. Indeed, collaborative governance may not merely facilitate account-giving and critical scrutiny, but also stimulate mutual learning and prompt government to react to critical feedback (Bovens et al. 2008; Brink and Wamsler 2018; Emerson and Gerlak 2014).

The accountability effect of collaborative governance may disappear if the private actors are becoming responsible for co-managing and co-delivering government solutions and thus lose their status as a relatively autonomous accountability forum. However, collaborative governance often involves external for-profit and non-profit actors in discussions of the problem diagnosis and discussion of possible solutions, leaving the responsibility for authoritative decision-making and implementation to public agencies, which in turn leaves considerable space for relevant and affected actors to critically scrutinize outputs and outcomes and to stimulate policy learning. Nevertheless, the accountability effect is conditioned on the ability of collaborative governance arrangements to spur trust-based deliberation between public and private actors with different interests, perspectives and views.

As broadly recognized in theories of collaborative governance, it is far from certain that collaborative governance works well and fulfils its potential in terms of making public governance more effective, democratic, innovative, etc. Successful collaborative governance calls for strategic efforts to design a political and institutional framework for collaborative interaction and to exercise a facilitative and integrative leadership (Agranoff 2006; Ansell and Torfing 2021; Bason 2018; Bryson et al. 2006; Doberstein 2016; Morse 2008; Page 2010). This kind of institutional framing and collaborative leadership issometimes referred to as metagovernance, defined as the efforts to influence collaborative processes without reverting too much to traditional forms of hierarchical imposition based on command and control (Author). Metagovernance allows governments to orchestrate and influence collaborative governance without undermining the relative autonomy of the actors that motivates them to participate and invest in constructing a common ground for joint problem-solving. Metagovernance involves the governance of self-governance and is typically performed through a combination of hands-off and hands-on tools (Author). The former refers to the political, institutional, financial and discursive framing of self-regulated collaboration, while the latter involves different forms of process management, such as trust-building, the selective activation of participants and conflict mediation and perhaps even the direct participation of meta-governors in order to set the agenda, clarify the decision-making premises and drive the process to conclusion.

The metagovernance of collaborative governance is essential regardless of the collaborative objective, and is therefore also necessary when the goal is to promote social accountability vis-à-vis public governance solutions. All of the relevant and affected actors must be brought to the table and incentivized to share knowledge and information with one another. Trust must be built to facilitate the critical scrutiny of past and present achievements and future plans, promote constructive dialogue, and stimulate mutual learning. Leaders must facilitate and catalyze the development and testing of new solutions, mobilize the participants in the implementation of new solutions and engage them in conversations about results and impacts that contribute to making fair and measured assessments and secure government responsiveness. A collaborative process is unlikely to foster critical, yet balanced and measured, assessments of responses to an emerging health crisis such as the recent pandemic if it does not involve health care staff, independent experts, patient organizations and intensely affected citizen groups all together, and if it does not facilitate public debate. This is achieved by carefully metagoverning the collaborative process. In other words, it requires an active strategic effort on the part of public authorities to enhance social accountability through collaborative governance; for example, by having national authorities ensure that regional and local authorities respond to criticisms arising from social and economic participants in collaborative governance (Schillemans 2008). The precise form and content of metagovernance strategies for enhanced social accountability is a topic for further research. Before moving on to propose a theoretical framework for the empirical research of these matters, however, it is necessary to consider the fact that collaborative governance is not only a part of the solution, but is also a part of the problem.

2.3. Holding Collaborative Governance Arenas to Account

As mentioned earlier, the participants in collaborative governance processes are often sub-elites representing different groups of affected citizens. Their ability to act on behalf of a broader group of citizens when engaging in collaborative governance and scrutinizing past and present endeavors and future intentions is exactly what makes them valuable components in an enabling environment for social accountability. However, the ability of sub elites to exploit their stakeholder status to gain influence on public governance is also what makes them dangerous, because it is difficult for the citizens and local communities that they claim to represent to hold the sub-elites to account for the solutions they are co-creating with government officials. Indeed, sub-elites are not merely playing the role as critical watchdogs, but are also participating in the production of new solutions for which they too will be responsible, and they might therefore be less critical and less interested in accountability issues, the more responsibility they take for the final decisions. Hence, if the sub-elites are ultimately op-opted by the governing elites that are metagoverning and participating in the collaborative arenas, there will be an urgent need for holding the entire collaboration to account for its actions and inaction.

Recent research clearly demonstrates the accountability deficit of networks, partnerships and other collaborative governance arenas (Damgaard and Lewis 2014; de Fine Licht and Naurin 2016; Fox 2015; Klijn and Koppenjan 2014; Willems and Van Dooren 2011). Hence, while collaborative governance may help to hold governments to account for governance problems, including policy and regulation failures and poor service provision, the collaborative governance themselves tend to be relatively opaque and secluded vis-à-vis external actors, who are not directly represented in the collaborative arena. This heightens the risk of the general public not knowing who participates, what is being discussed, what is decided, what are the results and impact, and who is to blame when collaborative governance efforts go wrong. Moreover, the relative autonomy of collaborative governance processes implies that public authorities have limited sanctioning powers at their disposal, and the fact that the participants are often appointed rather than elected (and sometimes even self-appointed) means that citizens cannot vote them out of office (Benz and Papadopoulos 2006; O’Flynn and Wanna 2008; Papadopoulos 2007; Rose and Sharfman 2014).

In much the same ways as collaborative governance enhances the social accountability of government, social accountability may also enhance the accountability of collaborative governance arrangements. Hence, a social accountability perspective suggests that the route to holding collaborative forms of governance to account is to empower citizens, neighborhoods and civic organizations by strengthening their political efficacy and capacity to critically scrutinize and contest what they are told not only by political and administrative elites, but also by sub-elites participating in collaborative governance arrangements (Joshi and Houtzager 2012). In other words, the path forward to enhanced accountability is to build a participatory culture and infrastructure in civil society. In such a participatory culture, service users, affected citizens, NGOs, private businesses etc., have rights and opportunities to speak out. They demand short, accessible and non-technical accounts of the content and effectiveness of collaborative governance solutions, keep track of and monitor what networks and partnerships are doing, and challenge them to explain and justify their role in and the consequences of collaborative governance solutions. They may also request that collaborative arenas engage with affected constituencies that are critical of either the process or the results. Local media may support their efforts to hold collaborative governance arenas to account for their actions by giving voice to criticisms, and public meta-governors at higher levels may add teeth to their critical voices by demanding that the collaborative arenas respond to public criticisms, correct mishaps and improve ill-devised solutions (Schillemans 2008). As illustrated by a case study of collaborative governance in the field of transport and mobility in Denmark, a participatory culture may urge local partnerships and networks to account for their actions on websites, in local media and at open meetings, all of which allows public scrutiny and critical judgement by those affected by collaborative governance solutions. Some of the local network actors even went to Germany to discuss the environmental consequences of a proposed bridge across the Fehmarn Belt with skeptical German citizens and grassroot organizations (Torfing et al. 2009). It takes time to develop a participatory culture in civil society that spurs participation in collaborative governance while simultaneously urging collaborative governance arenas to ensure the conditions for social accountability, and the societal conditions for such a culture to emerge may differ, depending on state and governance traditions (Vink et al. 2015; Voorberg et al. 2017). The EU-financed research project TROPICO has developed a tool kit that may support this process (https://tropico-project.eu/, accessed on 20 October 2021).

While some social accountability scholars primarily stress the need to encourage this kind of bottom-up social accountability through the mobilization and empowerment of local citizens, communities and movements (Joshi and Houtzager 2012), others stress the importance of top-down measures to stimulate and support social accountability (Fox 2015; Schillemans 2008). Hence, governments play a key role in creating a climate and infrastructure for promoting the social accountability of collaborative governance processes and in stepping in to take action when citizens, local media or social communities reveal problems relating to the process and outcomes of collaborative governance. Fox (2015) usefully proposes a ‘sandwich strategy’ combining the bottom-up empowerment of citizens and civil society with top-down government framing and stimulation of accountability. Since top-down attempts to promote accountability in relation to collaborative governance arrangements can easily undermine the relative autonomy that motivates actors to engage in collaborative governance, the devil lies in how to balance different forms of metagovernance (Sørensen and Torfing 2009, 2017). The many contributions to the literature on how to metagovern networks, partnerships and other collaborative forms of governance have much to offer in sketching out how this can be done (Kooiman 2003; Meuleman 2008; Sørensen and Torfing 2009; Voets et al. 2015). Drawing on this literature, it seems particularly promising for governments to use hands-off tools such as the design of funding schemes for partnerships and networks that commit them to communicating their activities and achievements to the public, together with hands-on tools such as facilitating public meetings that bring together network participants and their local constituencies in a critical exchange, focusing on problems, solutions and outcomes. Even a well-crafted metagovernance of collaborative governance arenas cannot ensure their social accountability vis-à-vis affected constituencies since the dependence of local actors on public finance and government regulation may undermine their independence and silence their critical voices.

3. A Heuristic Conceptual Framework for Future Research and Prospective Analysis

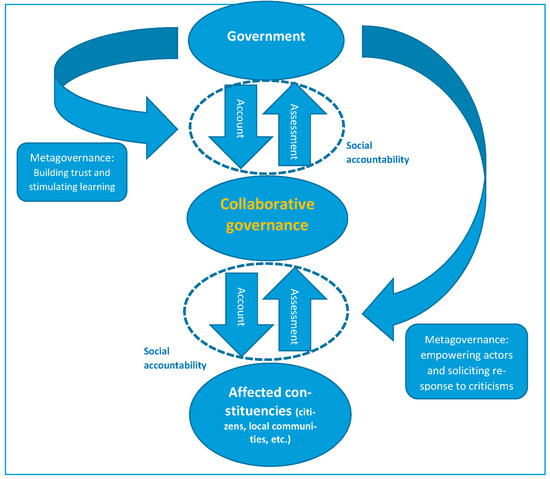

The argument above has sought to justify two interrelated propositions. The first proposition is that a strategic use of collaborative governance can contribute to making public governance accountability thicker than is currently the case in advanced liberal democracies by providing an enabling environment for social accountability. The second is that social accountability can also help to hold rather externally secluded arenas of collaborative governance involving a particular set of public decision-makers and private sub-elites to account for their plans, doings and achievements. These propositions remain largely untested (but see Cornwall and Shankland 2008; Peruzzotti and Smulovitz 2006; Torfing et al. 2009). Hence, there is an urgent need to further examine their feasibility through comparative studies, explore under what conditions collaborative governance enhances government accountability and collaborative governance arenas engages with affected constituencies, and how the double impact of social accountability can be optimized through metagovernance. Figure 1 draws the basic contours of a conceptual framework that may guide empirical studies through the impact of collaborative governance as a form of social accountability on government accountability and the impact of social accountability on the accountability of collaborative governance arenas. The two-stage model also aims to capture if and how government actors deploy metagovernance as a tool for ensuring government accountability vis-à-vis-collaborative governance arenas and for advancing social accountability in relation to collaborative governance processes.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for studying the double impact of social accountability on public governance accountability.

The framework is heuristic in the sense that it provides the conceptual resources and ideas needed to further investigate the connections between government, collaborative governance and affected constituencies while paying attention to contextual factors and adjusting the propositions based on learning and empirical discoveries. Hence, it does not provide a detailed manual for analyzing the impact of collaborative governance on public governance accountability and further studying the double impact of social accountability that helps to improve public governance accountability by linking government to collaborative accountability forums while subsequently serving to ensure that collaborative governance arenas are accountable to affected constituencies such as citizens, local communities and civic organizations acting on their behalf.

The contribution of the two-stage model lies in its visualization of, first, the need to analyze public governance accountability as an outcome of high-quality exchanges between government officials and stakeholders participating in collaborative governance, and, second, the need to facilitate interaction between the sub-elites involved in collaborative governance and the affected constituencies they claim to represent (Saward 2010). The conceptual framework thus draws attention to the fact that public governance accountability is not merely ensured by traditional horizontal and vertical accountability mechanisms such as checks and balances and regular elections, as it also involves the construction of an enabling environment for social accountability produced in and through collaborative governance arrangements that are metagoverned by government. It also highlights the accountability-relevant exchanges between collaborative governance arrangements and relevant and affected citizens and civil society actors that may hold the collaborating sub-elites to account and do so in the shadow of hierarchy, as public meta-governors may help to empower citizens to demand and scrutinize accounts and encourage collaborative arenas to provide accessible, non-technical accounts.

Based on the conceptual components and connections displayed in Figure 1, we believe that studies of how collaborative governance can increase the answerability of government and how civil constituencies can increase the accountability of collaborative governance arenas may benefit from the following five steps:

The first step is to map the different forms of cross-boundary collaboration in relation to a particular policy issue and governance process and assess whether the public and private actors engage in a high-quality exchange wherein public actors get to explain themselves and private actors are able to question, scrutinize and pass judgement on both extant policies (ex post accountability) and new, intended solutions (ex ante accountability). The mapping of actors and their interrelations may draw on Social Network Analysis to establish the pattern of interaction between the public and private actors (Knoke and Yang 2019), but this analysis should be complemented by Policy Network Analysis aiming to determine the form and content of the interaction and in which part of the policy process the interaction took place (Rhodes 2008). It will also be important to analyze the degree of mutual trust and how it sustains an open, frank discussion about the perception of the problem at hand, the course of action that has been or will be taken, and the ensuing or likely results thereof (Klijn et al. 2010). Positive trust spirals where trust and high-quality exchanges feed into each other may be detected.

The second step is to assess whether and how the collaborative exchange between public decision-makers and private sub-elites leads to critical yet nuanced and measured evaluations of government action and joint solutions and whether these evaluations result in sanctions, such as naming and shaming and/or learning-based changes in public governance. Alternatively, problematic issues raised in and by collaborative governance arenas may prompt action from the established system of vertical and horizontal accountability. Analysis of the critical scrutiny of government action in collaborative settings may seek to unravel whether participating stakeholders use policy evaluation as a means to hold government to account, stimulate policy learning, or manipulate political opportunity structures to their own advantage (Schoenefeld and Jordan 2019). It may also study the conditions for government actors and external stakeholders to avoid engaging in unconstructive blame games that fail to provide accountability (Pellinen et al. 2018). Finally, the analysis must pay attention to both the risk of arena capture by strong interest organizations and the risk of external stakeholders being too weak to go up against government interests. Hence, analyzing shifting power relations is crucial.

The third step is to analyze how government agencies metagovern the relevant collaborative governance arenas in order to encourage and support their functioning as an enabling environment for the production of social accountability (Jenkins 2014). Would-be metagovernors can use hands-off tools to design an inclusive arena for collaborative governance and frame it so as to include joint policy evaluation in the remit. They can also use hands-on tools to build trust between public and private actors (Six et al. 2010) and to insist that policy deliberation is both prospective and retrospective and is focused on mutual learning. The motivations for government to enhance social accountability through metagovernance may either be professional interest in policy learning or a wish to enhance legitimacy by improving accountability. Other forms of motivations, or lack thereof, must also be investigated.

The fourth step is to explore the extent to which collaborative governance arenas produce publicly available, non-technical and comprehensive accounts that relevant and affected citizens, communities and civil society organizations can access, question, scrutinize and voice their opinions about. Special attention should be paid to whether and how civil constituencies are motivated to spend time evaluating processes and outcomes of collaborative governance, how they engage in critical dialogue with the sub-elites involved in collaborative governance, and how they can sanction instances of bad governance, which might be a result of power inequalities and elite capture (McLaverty 2014) or a failure to understand the needs and conditions on the ground (Ansell et al. 2017).

The final step is to study how public authorities, perhaps at the initiative of local citizens, can support and strengthen the ability of citizens, local communities and civic organizations to critically assess what is going on in collaborative governance arenas and to demand compensatory or remedial action from governance networks if legitimate rights and interests have been neglected or violated (Brinkerhoff and Wetterberg 2016). The metagovernance of social accountability is important in the attempt to bolster local communities to hold collaborative governance arenas to account, but we need to know what tools are used and how effective they are.

The model and the five analytical steps not only reveal the double role of social accountability in, first, enhancing the accountability of government and, subsequently, in ensuring the accountability of collaborative governance arrangements. What is also revealed is the double role of metagovernance in, first, realizing the potential of collaborative governance to enhance government accountability and, subsequently, securing the accountability of collaborative governance vis-à-vis local constituencies. The first point is of great value for science and should include much more attention paid to social accountability in the future. The second point is of great relevance to practitioners who must assume responsibility for realizing the accountability potential of collaborative governance. Hitherto, metagovernance has mostly been discussed in relation to enhancing the impact of collaborative governance on effective, democratic and innovative governance (Sørensen and Torfing 2017). Now the concern for strengthening accountability through and of collaborative governance must be added to the list of possible metagovernance goals.

4. Conclusions

Although traditional forms of horizontal and vertical accountability are crucial for holding governments to account for their actions and inactions, they provide a thin form of accountability, and recent efforts to enhance public control with what governments do have not managed to silence the voices calling for a further strengthening of public governance accountability. This article has argued that the principal–agent perspective that has informed these accountability measures has little to offer when it comes to proposing news ways of securing adequate account-giving and well-informed and balanced assessments and effective responses. Although social accountability is mainly developed as a strategy for improving accountability in the Global South, with weak or absent state structures and failing democracies, we find that the social accountability perspective can also inspire the enhancement of public governance accountability in Western countries with well-institutionalized horizontal and vertical forms of accountability. Hence, intensifying and improving the quality of the exchanges between public authorities and increasingly competent and assertive citizens, neighborhoods and stakeholders may help create thicker public governance accountability by means of supplementing the traditional forms of democratic accountability with new forms of social accountability.

We have aimed to demonstrate that collaborative governance has the potential to serve as an enabling environment for the promotion of social accountability. Moreover, we have shown how collaborative forms of governance create their own accountability problems that can be solved by adding a second loop of social accountability that seeks to hold the collaborative governance arenas to account for their contribution to public problem solving. Together, these arguments counter the traditional criticism of the accountability problems associated with collaborative governance by highlighting its potential contribution to enhancing government accountability.

Finally, we have argued that the contribution of collaborative governance to the enhancement of supplementary forms of social accountability depends on metagovernance and that local citizens, communities and civil society organizations that may want to complain about the output and outcomes of collaborative governance can benefit from supportive metagovernance from government actors who can add teeth to the critical local voices.

All these arguments are captured by the two-stage model in Figure 1, which shows how public governance accountability can be enhanced through a double-loop social accountability model. The two stages of social accountability tend to make the contribution of collaborative governance to public sector accountability uncertain, as many things can go wrong. However, this is precisely why the model insists that metagovernance can play a key role in supporting bottom-up forms of social accountability. The implication for practitioners is clear: they must learn to metagovern collaborative governance processes and to assume responsibility for realizing their potential contribution to strengthening government accountability.

The double-loop social accountability model may serve as a heuristic device, guiding much-needed empirical studies that may test whether and under what conditions the new path to improved accountability is viable. Should empirical studies be affirmative, the questions will remain as to how to combine new and existing accountability mechanisms and how to avoid their combination from resulting in accountability overload (Lewis and Triantafillou 2012), although that is merely a problem for government and never for the citizens aiming to hold elected government to account. In case empirical studies identify examples of collaborative governance that are unhelpful in enhancing social accountability and thickening accountability, we need to identify the barriers and work with practitioners to conduct design experiments (Stoker and John 2009) to produce in situ knowledge of what it takes for collaborative governance arrangements to focus on accountability and enable affected groups of citizens to scrutinize their actions and inactions.

Government efforts to curb the COVID-19 crisis provide a highly relevant case for testing the two-stage model in a study of government accountability (Leoni et al. 2021; Rinaldi et al. 2020). In many Western countries, government actors have involved relevant and affected societal actors in crisis management, and while this may have enhanced dialogical accountability by allowing non-government actors to critically scrutinize the actions and inactions of government, it raises the question of how such collaborative governance arenas are held to account by wider society. This is exactly what the two-stage model aims to capture and applying it in comparative studies will help to generate valuable empirical experiences with its usage.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.S. and J.T.; methodology, E.S. and J.T.; software E.S. and J.T.; validation, E.S. and J.T.; formal analysis, E.S. and J.T.; investigation, E.S. and J.T.; resources, E.S. and J.T.; data curation, E.S. and J.T.; writing—original draft preparation, E.S. and J.T.; writing—review and editing, E.S. and J.T.; visualization, E.S. and J.T.; supervision, E.S. and J.T.; project administration, E.S. and J.T.; funding acquisition, E.S. and J.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by EU Horizon 2020 TROPICO grant # 726840.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Agger, Annika, Bodil Damgaard, Andreas H. Krogh, and Eva Sørensen, eds. 2015. Collaborative Governance and Public Innovation in Northern Europe. London: Bentham Science Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Agranoff, Robert. 2006. Inside Collaborative Networks: Ten Lessons for Public Managers. Public Administration Review 66: 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agranoff, Robert, and Michael McGuire. 2003. Collaborative Public Management: New Strategies for Local Governments. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alford, John. 2014. The Multiple Facets of Co-Production: Building on the Work of Elinor Ostrom. Public Management Review 16: 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, Christoper, and Alison Gash. 2008. Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18: 543–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, Christopher, and Jacob Torfing. 2021. Public Governance as Co-creation: A Strategy for Revitalizing the Public Sector and Rejuvenating Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ansell, C., E. Sørensen, and J. Torfing. 2017. Improving Policy Implementation through Collaborative Policymaking. Policy & Politics 45: 467–486. [Google Scholar]

- Ansell, Christopher, and Jarle Trondal. 2018. Governing Turbulence: An Organizational-Institutional Agenda. Perspectives on Public Management and Governance 1: 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, Christopher, Carey Doberstein, Hayley Henderson, Saba Siddiki, and Paul ‘t Hart. 2020. Understanding Inclusion in Collaborative Governance. Policy and Society 39: 570–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antlöv, Hans, and Anna Wetterberg. 2021. Deliberate and Deliver–Deepening Indonesian Democracy through Social Accountability. In Deliberative Democracy in Asia. Edited by B. He, M. Breen and J. Fishkin. New York: Routledge, chapter 3. [Google Scholar]

- Ashworth, Scott, Ethan B. de Mesquita, and Amanda Friedenberg. 2017. Accountability and Information in Elections. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics 9: 95–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attard, Judie, Fabrizio Orlandi, Simon Scerri, and Sören Auer. 2015. A Systematic Review of Open Government Data Initiatives. Government Information Quarterly 32: 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, Benjamin. 1984. Strong Democracy: Participatory Politics for a New Age. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, James, Jonathan Birdwell, and Mark Littler. 2011. The New Face of Digital Populism. London: Demos. [Google Scholar]

- Bason, Christian. 2018. Leading Public Sector Innovation: Co-Creating for a Better Society. Bristol: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Behn, Robert D. 2001. Rethinking Democratic Accountability. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- Benz, Arthur, and Ioannis Papadopoulos, eds. 2006. Governance and Democracy: Comparing National, European and International Experiences. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, Carmine, Greta Nasi, and William Rivenbark. 2021. Implementing Collaborative Governance: Models, Experiences, and Challenges. Public Management Review. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bommert, Benjamin. 2010. Collaborative Innovation in the Public Sector. International Public Management Review 11: 15–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bovens, Mark, and Anchrit Wille. 2020. Indexing Watchdog Accountability Powers a Framework for Assessing the Accountability Capacity of Independent Oversight Institutions. Regulation & Governance 15: 856–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovens, Mark, Thomas Schillemans, and Paul ‘t Hart. 2008. Does Public Accountability Work? An Assessment Tool. Public Administration 86: 225–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovens, Mark, Robert E. Goodin, and Thomass Schillemans, eds. 2014a. The Oxford Handbook of Public Accountability. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bovens, Mark, Thomas Schillemans, and Robert E. Goodin. 2014b. Public Accountability. In The Oxford Handbook Public Accountability. Edited by Mark Bovens, Robert E. Goodin and Thomas Schillemans. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Breuer, Anita, and Julia Leininger. 2021. Horizontal Accountability for SDG Implementation: A Comparative Cross-National Analysis of Emerging National Accountability Regimes. Sustainability 13: 7002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, Ebba, and Christine Wamsler. 2018. Collaborative Governance for Climate Change Adaptation: Mapping Citizen–municipality Interactions. Environmental Policy and Governance 28: 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkerhoff, Derick W., and Anna Wetterberg. 2016. Gauging the Effects of Social Accountability on Services, Governance, and Citizen Empowerment. Public Administration Review 76: 274–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, John M., Barbara C. Crosby, and Melissa M. Stone. 2006. The Design and Implementation of Cross-Sector Collaborations: Propositions from the Literature. Public Administration Review 66: 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, John, Barbara C. Crosby, and Laura Bloomberg, eds. 2015. Creating Public Value in Practice: Advancing the Common Good in a Multi-Sector, Shared-Power, No-One-Wholly-in-Charge World. Boca Raton: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, James M. 2003. Transforming Leadership. New York: Atlantic Monthly. [Google Scholar]

- Candeub, Adam. 2013. Transparency in the Administrative State. Houston Law Review 51: 385–403. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, Tom, and Per Lægreid. 2015. Performance and Accountability: A Theoretical Discussion and an Empirical Assessment. Public Organization Review 15: 207–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiano, Thomas. 2018. The Rule of the Many: Fundamental Issues in Democratic Theory. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, Amanda, and Mary Francoli. 2014. What’s in a Name? A Comparison of ‘Open Government’ Definitions across Seven Open Government Partnership Members. Journal of e-Democracy and Open Government 6: 248–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Compton, Mallory, Scott Douglas, Lauren Fahy, Joannah Luetjens, Paul ‘t Hart, and Judith Van Erp. 2021. New Development: Walk on the Bright Side—What Might We Learn about Public Governance by Studying its Achievements? Public Money & Management, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwall, Andrea, and Alex Shankland. 2008. Engaging Citizens: Lessons from Building Brazil’s National Health System. Social Science & Medicine 66: 2173–84. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby, Barbara C., and John M. Bryson. 2005. Leadership for the Common Good. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby, Barbara C., and John M. Bryson. 2010. Integrative Leadership and the Creation and Maintenance of Cross-Sector Collaborations. The Leadership Quarterly 21: 211–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, Russell J., and Christian Welzel, eds. 2014. The Civic Culture Transformed: From Allegiant to Assertive Citizens. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Damgaard, Bodil, and Jenny Lewis. 2014. Citizen Participation in Public Accountability. In The Oxford Handbook Public Accountability. Edited by M. Bovens, R. E. Goodin and T. Schillemans. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 258–72. [Google Scholar]

- de Benedictis-Kessner, Justin, and Christopher Warshaw. 2020. Accountability for the Local Economy at All Levels of Government in United States Elections. American Political Science Review 114: 660–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Fine Licht, Jenny, and Daniel Naurin. 2016. Transparency. In Handbook on Theories of Governance. Edited by Chritopher Ansell and Jacob Torfing. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 217–24. [Google Scholar]

- De Montesquieu, Charles. 1989. The Spirit of the Laws. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. First published 1748. [Google Scholar]

- Dillard, Jesse, and Eija Vinnari. 2019. Critical Dialogical Accountability: From Accounting-based Accountability to Accountability-based Accounting. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 62: 16–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doberstein, Carey. 2016. Designing Collaborative Governance Decision-Making in Search of a ‘Collaborative Advantage’. Public Management Review 18: 819–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, Scott, Christopher Ansell, Charles F. Parker, Eva Sørensen, Paul ‘t Hart, and Jacob Torfing. 2020. Understanding Collaboration: Introducing the Collaborative Governance Case Databank. Policy and Society 39: 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, Scott, Thomas Schillemans, Paul ‘t Hart, Christopher Ansell, Lotte Bøgh Andersenc, Matthew Flinders, Brian Heade, Donald Moynihanf, Tina Nabatchi, Janine O’Flynn, and et al. 2021. Rising to Ostrom’s Challenge: An Invitation to Walk on the Bright Side of Public Governance and Public Service. Policy Design and Practice. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubnick, Mel J. 2003. Accountability through Thick and Thin. East Lansing: Institute of Governance Public Policy and Social Research. [Google Scholar]

- Dudley, Emma, Dinan Y. Lin, Matteo Mancini, and Jonathan Ng. 2015. Implementing a Citizen-Centric Approach to Delivering Government Services. New York: McKinsey & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, Kirk, and Andrea K. Gerlak. 2014. Adaptation in Collaborative Governance Regimes. Environmental Management 54: 768–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, Kirk, and Tina Nabatchi. 2015. Collaborative Governance Regimes. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, Kirk, Tina Nabatchi, and Stephen Balogh. 2012. An Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 22: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmark, Anders. 2007. Democratic Accountability and Network Governance—Problems and Potentials. In Theories of Democratic Network Governance. Edited by Eva Sørensen and Jacob Torfing. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 274–96. [Google Scholar]

- Esser, Frank, and Jesper Strömbäck, eds. 2014. Mediatization of Politics: Understanding the Transformation of Western Democracies. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Etzioni-Halevy, Eva. 1993. The Elite Connection: Problems and Potential of Western Democracy. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi, Mahboubeh, and Mohammad R. Behmanesh. 2012. New Public Management Approach and Accountability. International Journal of Management, Economics and Social Sciences 1: 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Feruglio, Franscesca, and Nicholas Nisbett. 2018. The Challenges of Institutionalizing Community-level Social Accountability Mechanisms for Health and Nutrition: A Qualitative Study in Odisha, India. BMC Health Services Research 18: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, Jobathan A. 2015. Social Accountability: What Does the Evidence Really Say? World Development 72: 346–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedom House. 2020. Government Accountability and Transparency. Downloaded. 2020. Available online: https://freedomhouse.org/issues/government-accountability-transparency (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Fung, Archon. 2015. Putting the Public Back into Governance. Public Administration Review 75: 513–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gailmard, Sean. 2014. Accountability and Principal–Agent Theory. In The Oxford Handbook of Public Accountability. Edited by Mark Bovens, Robert E. Goodin and Thomas Schillemans. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 90–105. [Google Scholar]

- Ghose, Rina. 2005. The Complexities of Citizen Participation through Collaborative Governance. Space and Polity 9: 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, Charles T., and Sonia K. Katyal. 2020. From Trade Secrecy to Seclusion. Georgetown Law Journal 109: 1337. [Google Scholar]

- Grimes, Marcia. 2013. The Contingencies of Societal Accountability: Examining the Link between Civil Society and Good Government. Studies in Comparative International Development 48: 380–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardin, Russell. 2002. Trust and Trustworthiness. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Held, David. 2006. Models of Democracy. Boston: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hickey, Sam, and Sophie King. 2016. Understanding Social Accountability: Politics, Power and Building New Social Contracts. The Journal of Development Studies 52: 1225–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirst, Paul. 2000. Democracy and Governance. In Debating Governance. Edited by Jon Pierre. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 13–35. [Google Scholar]

- Holbein, John B., and Hans J. Hassell. 2019. When your Group Fails: The Effect of Race-based Performance Signals on Citizen Voice and Exit. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 29: 268–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]