Redefining the Use of Sustainable Development Goals at the Organisation and Project Levels—A Survey of Engineers

Abstract

1. Introduction

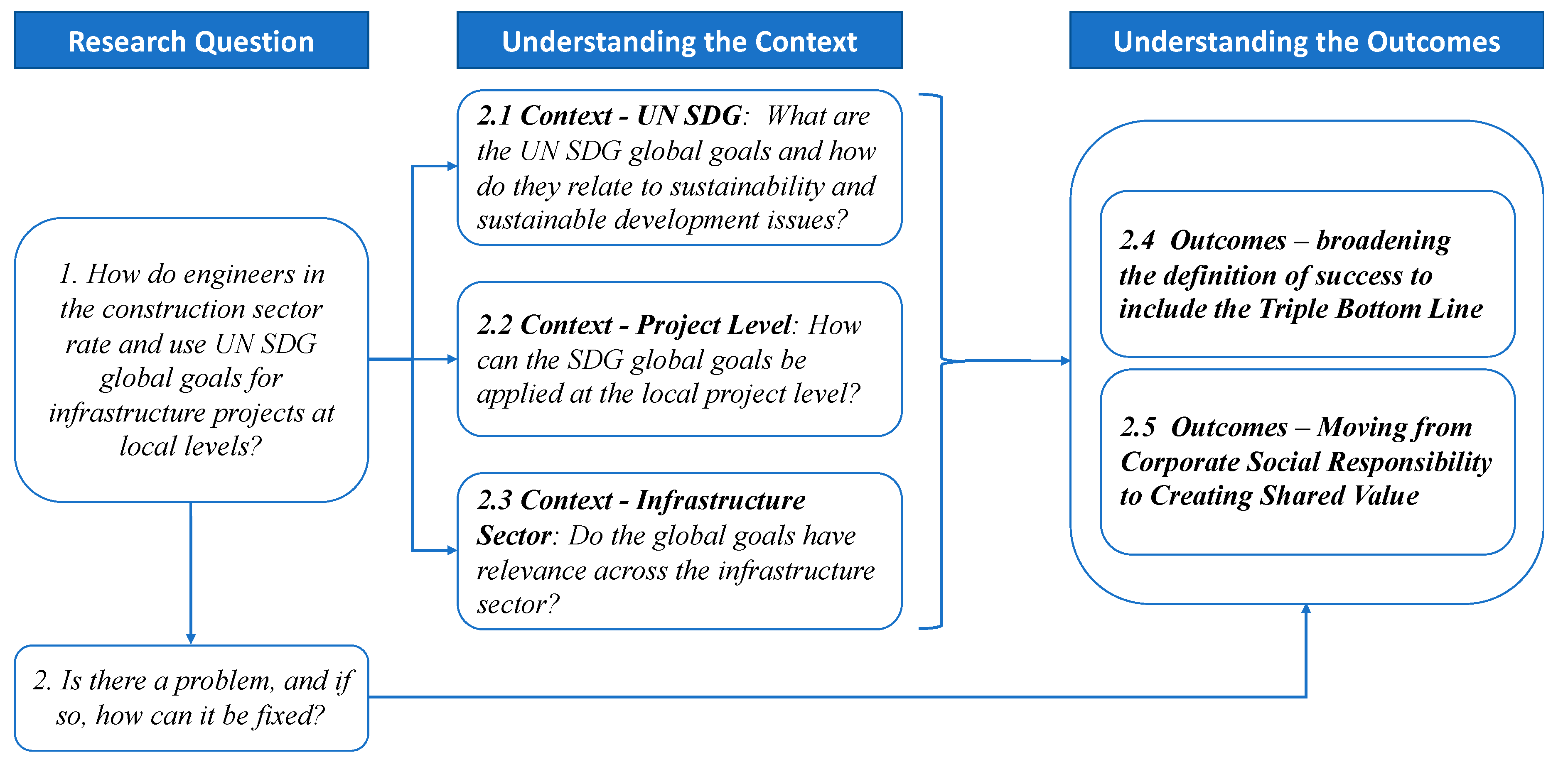

2. Literature Review

2.1. Context—United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

2.2. Context—Global SDGs at the Project Level

2.3. Context—Global SDGs in the Construction Sector

2.4. Outcomes—Broadening the Definition of Success to Include the Triple Bottom Line

2.5. Outcomes—Moving from Corporate Social Responsibility to Creating Shared Value

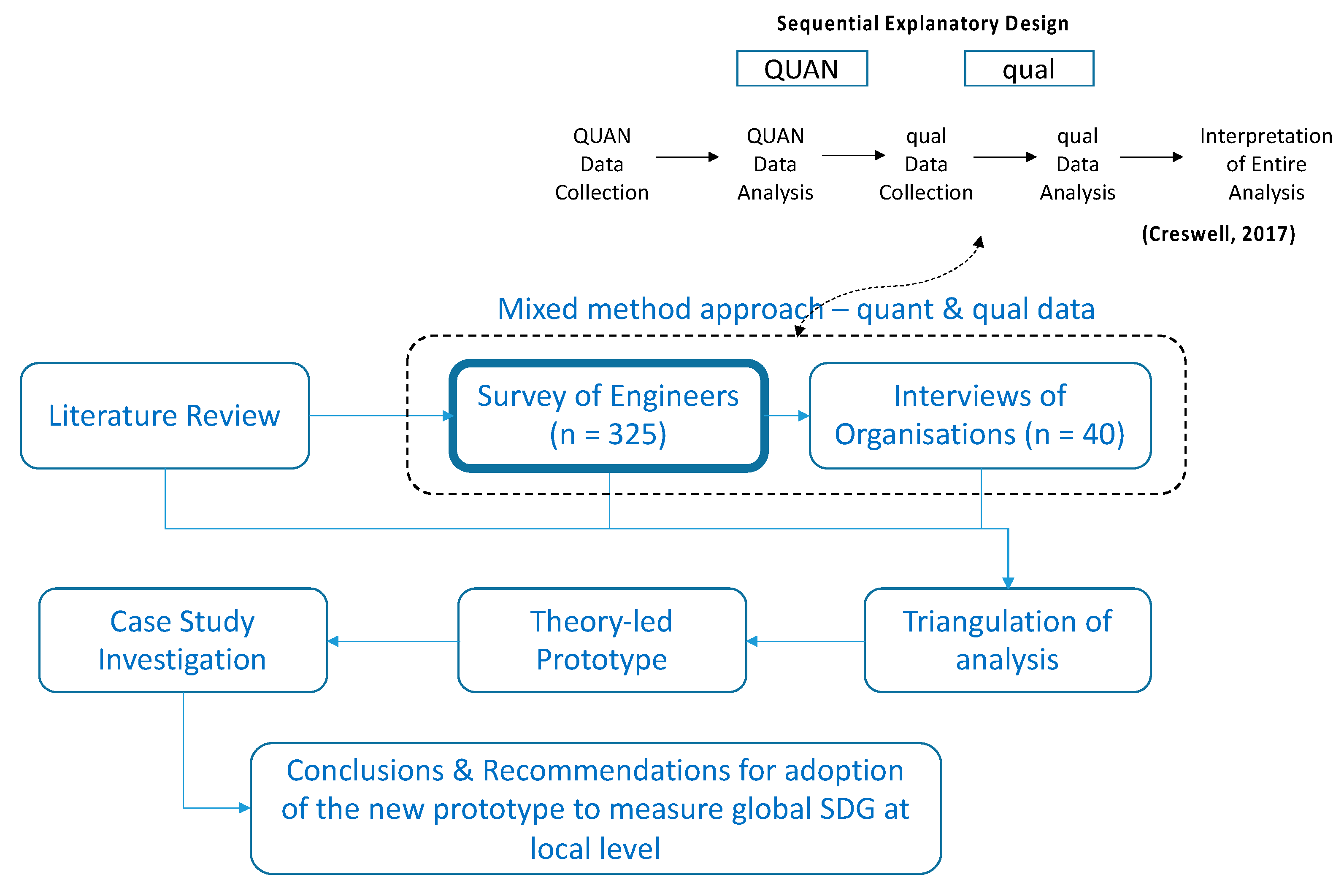

3. Methodology

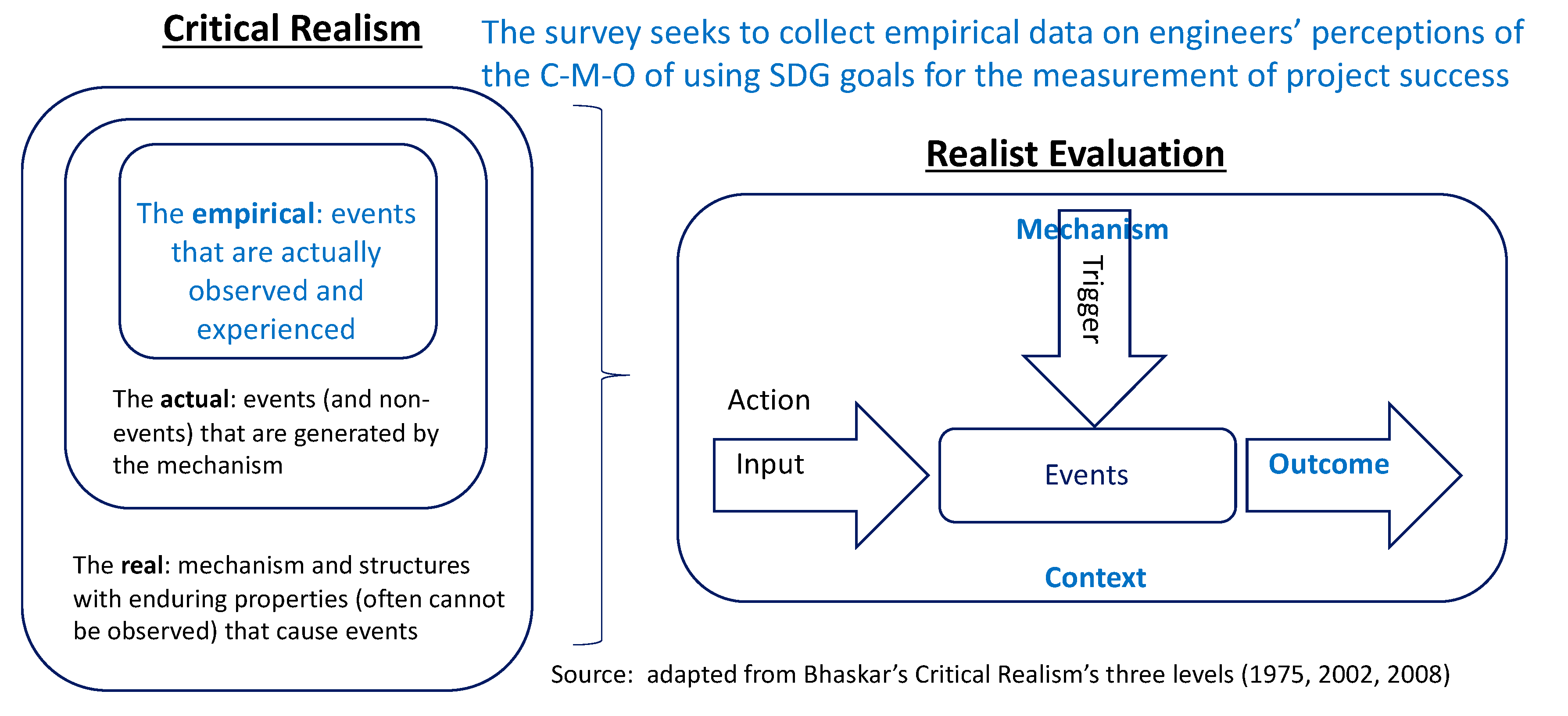

3.1. Using the Realist Evaluation Methodology to Structure the Survey

- Context: The conditions in a context of action encompass ‘material resources and social structures, including the conventions, rules and systems of meaning in terms of which reasons are formulated’ (Sayer 1992, p. 112; in Easton 2010).

- Mechanism: The underlying entities, processes, or structures which operate in particular contexts to generate outcomes of interest (Astbury and Leeuw 2010, p. 386).

- Outcome: The practical effects produced by causal mechanisms being triggered in a given context (Tilley 2016, p. 145).

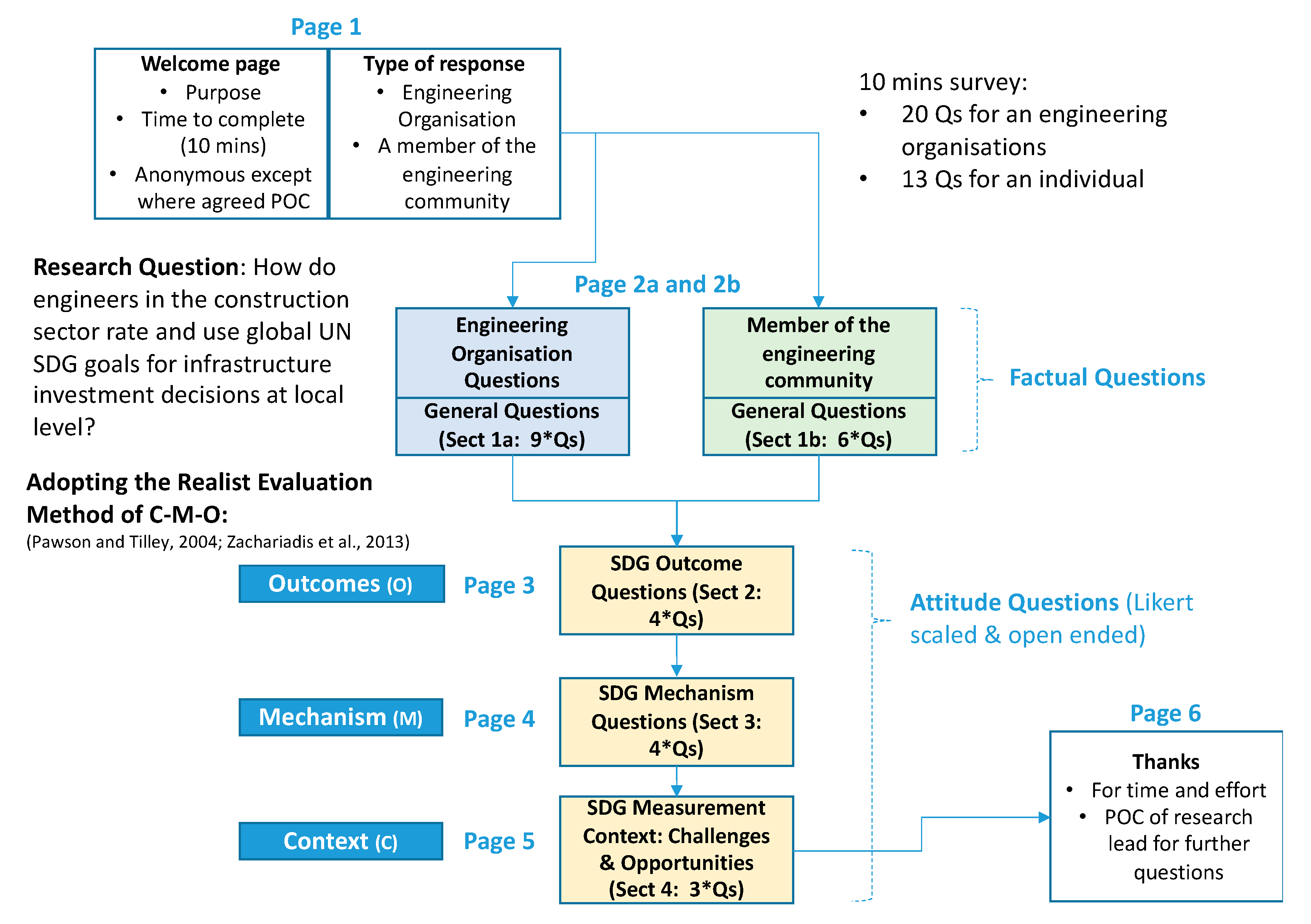

3.2. The Survey

3.3. Access

4. Data Analysis and Results

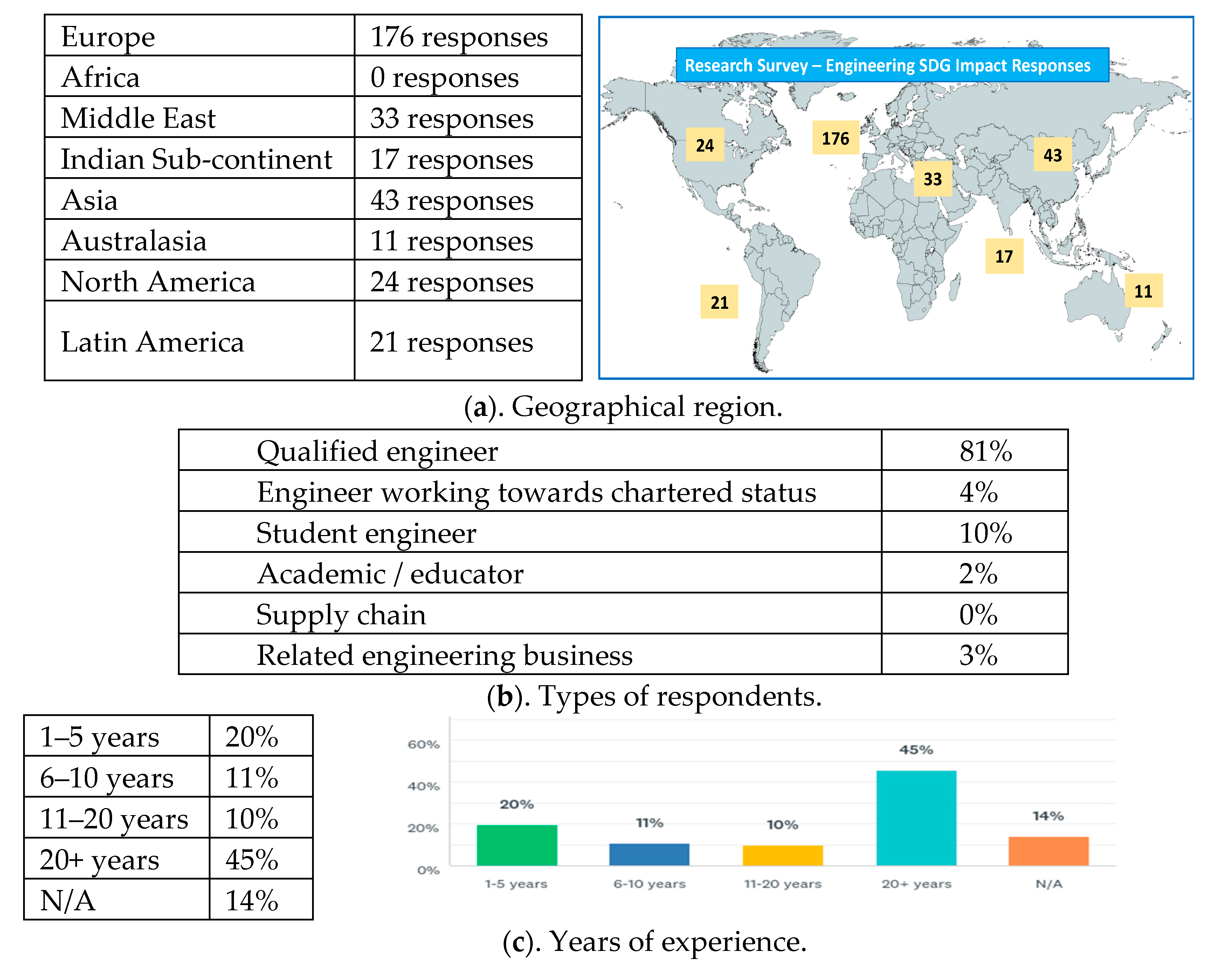

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Survey Results

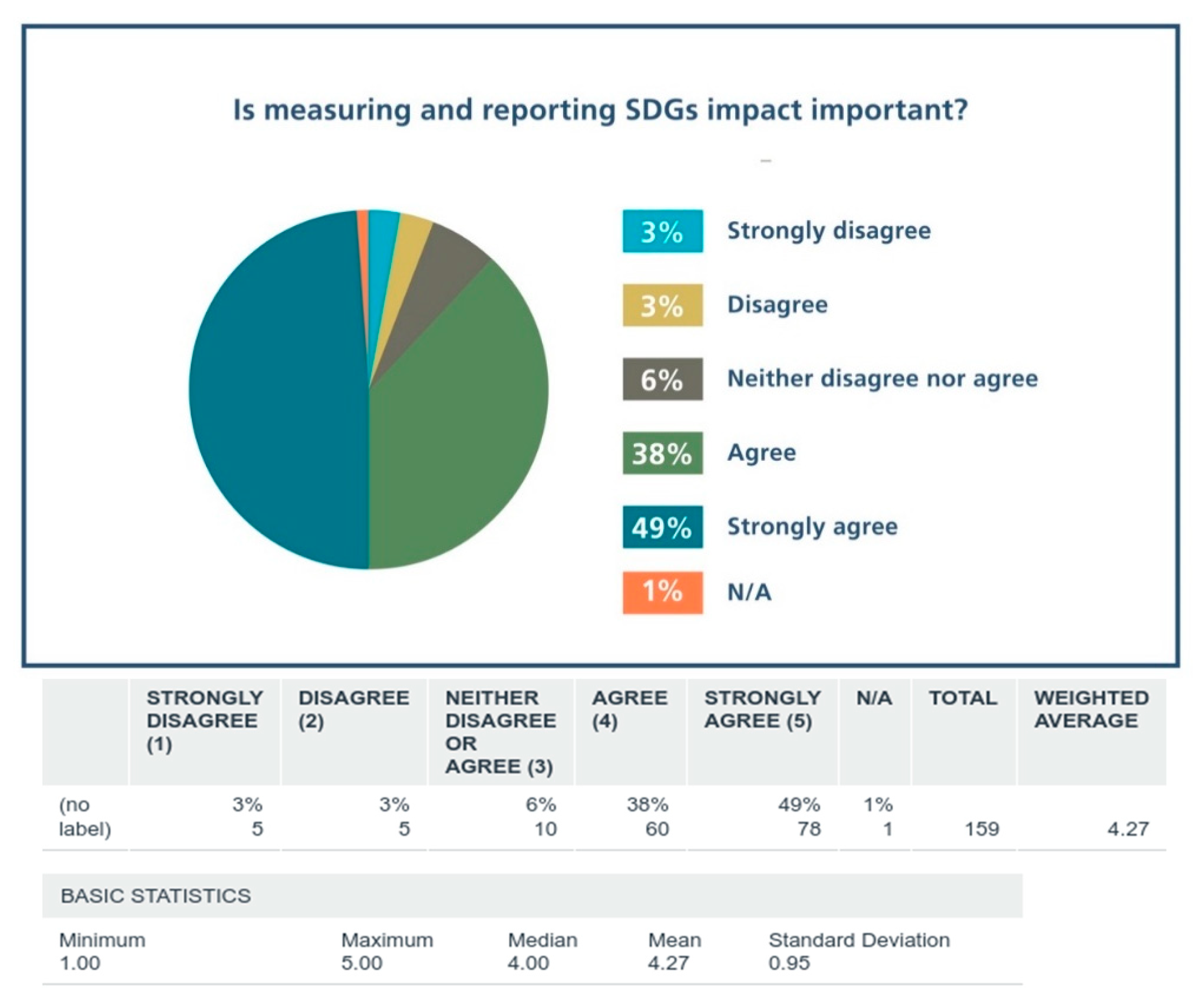

4.2.1. Question 1 (Outcomes): Should Engineering Businesses Seek Ways to Measure and Report SDG Impact?

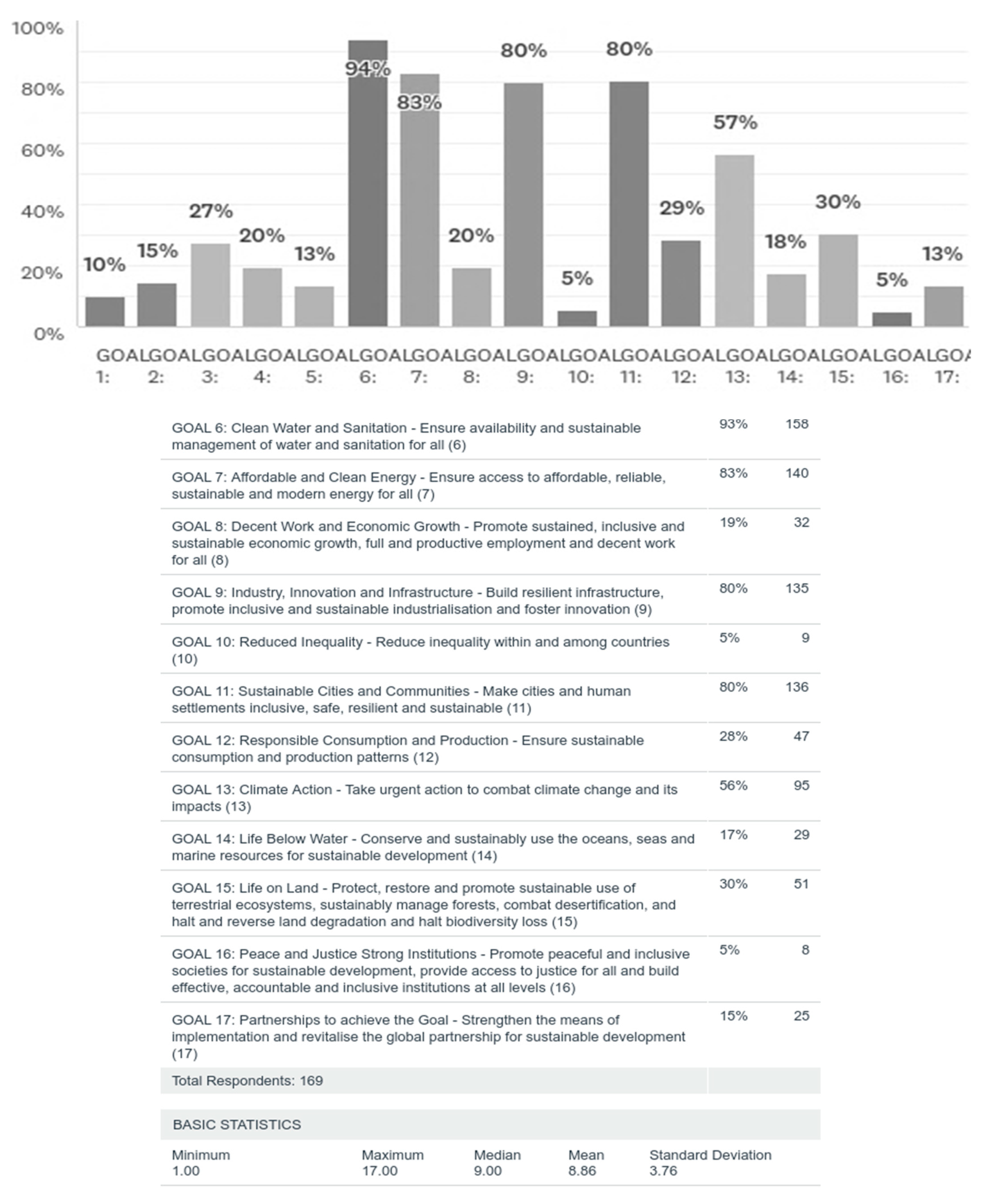

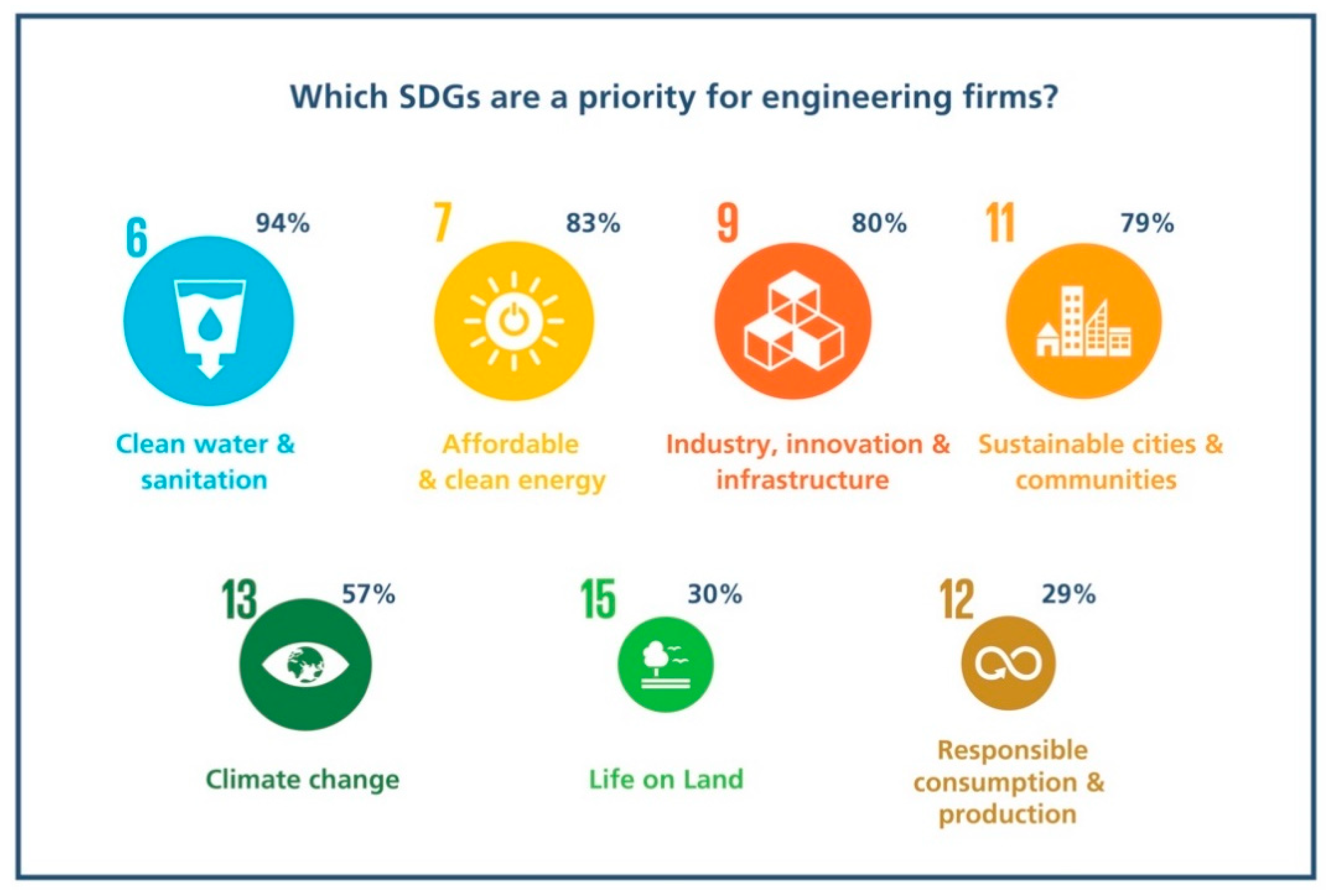

4.2.2. Question 2 (Outcomes): What Are the Top 5 SDG Goals Most Relevant to Measuring Impact of Your Infrastructure Projects and Programmes?

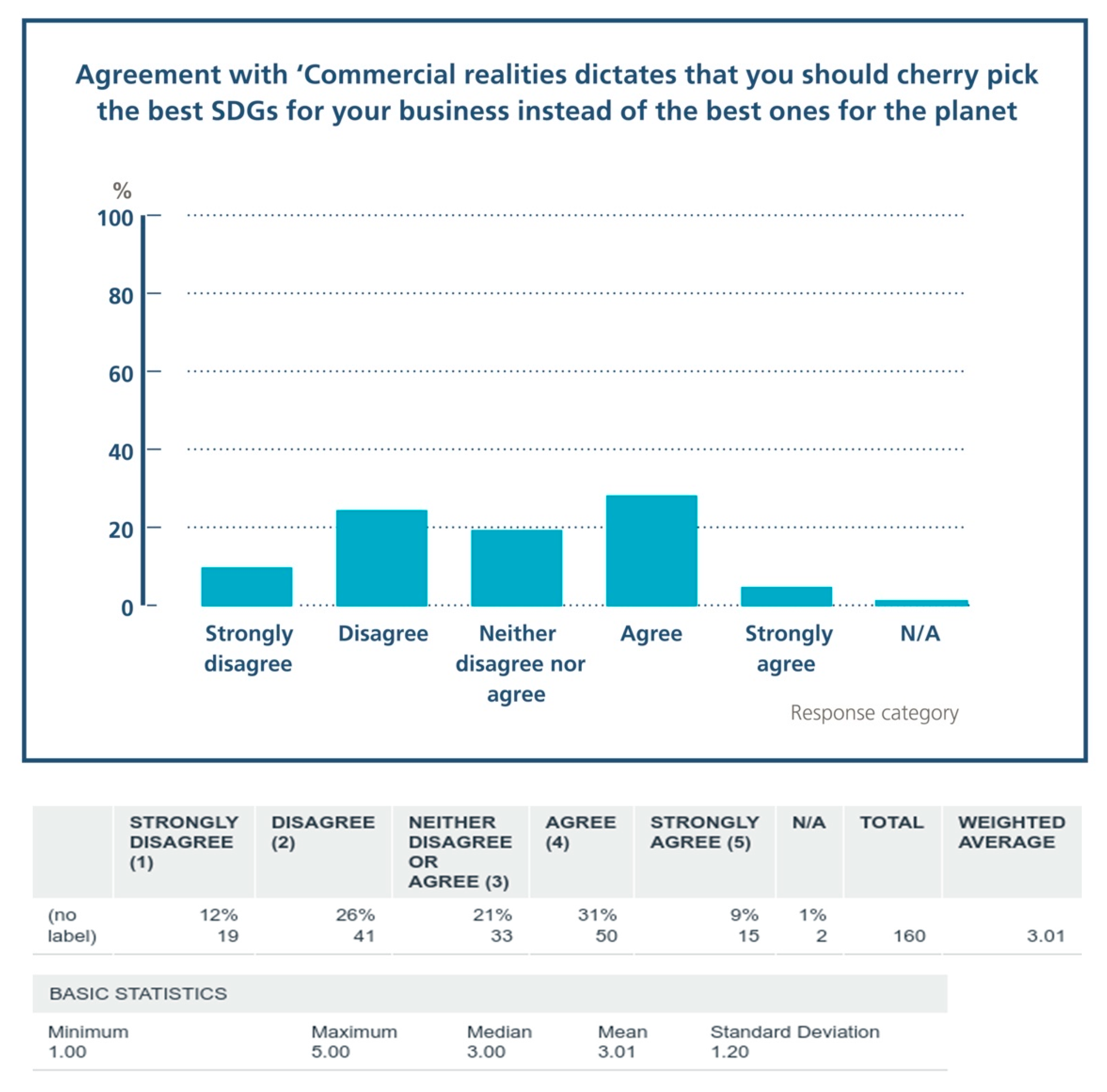

4.2.3. Question 3 (Mechanism): Do Commercial Realities Dictate the SDGs You Pick?

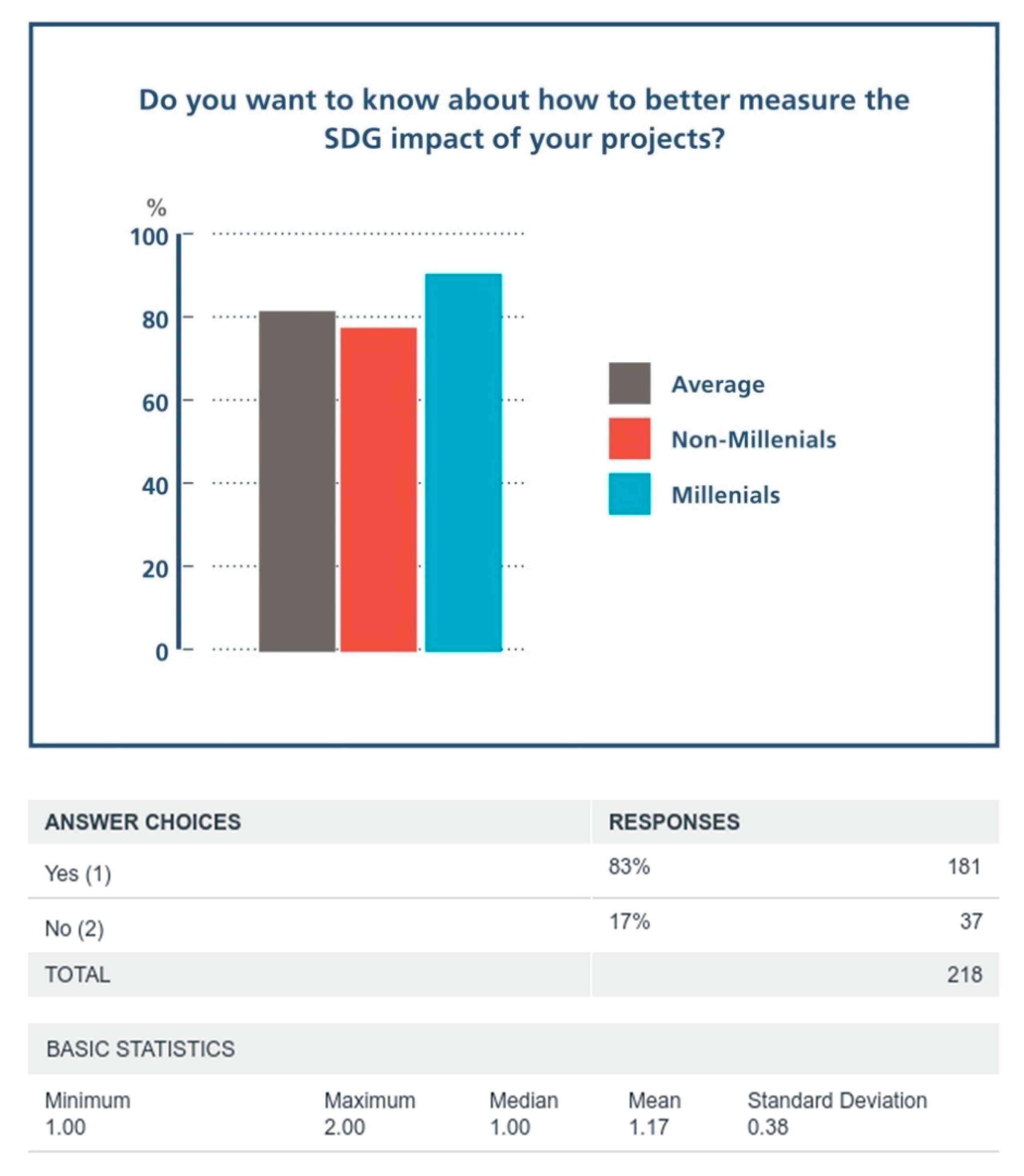

4.2.4. Question 4 (Mechanism): Do You Want to Know more about Measuring SDG Impact on Your Projects?

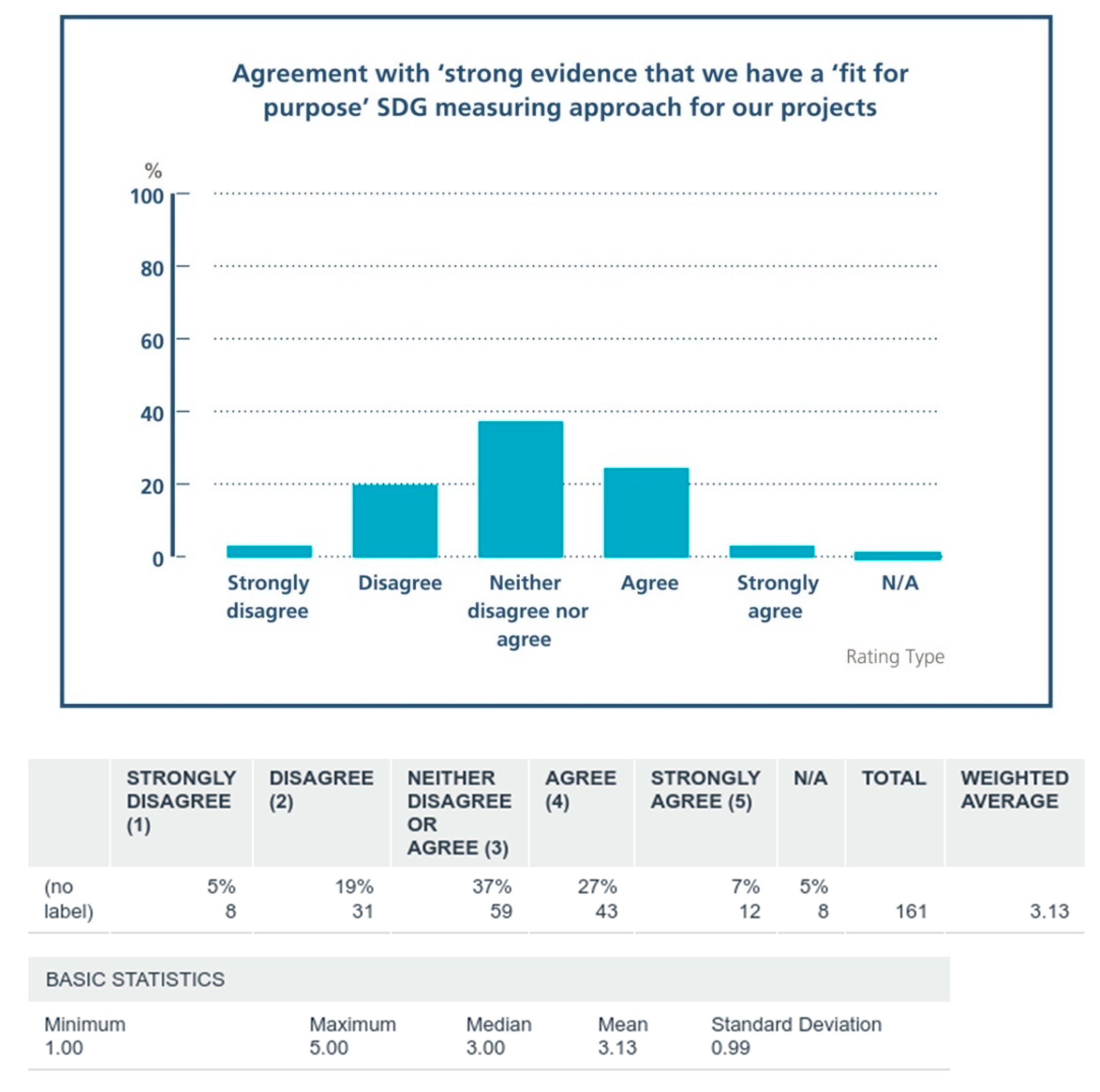

4.2.5. Question 5 (Mechanism): What Is the Engineers’ View on Current Infrastructure Projects and Their Achievement of the SDGs?

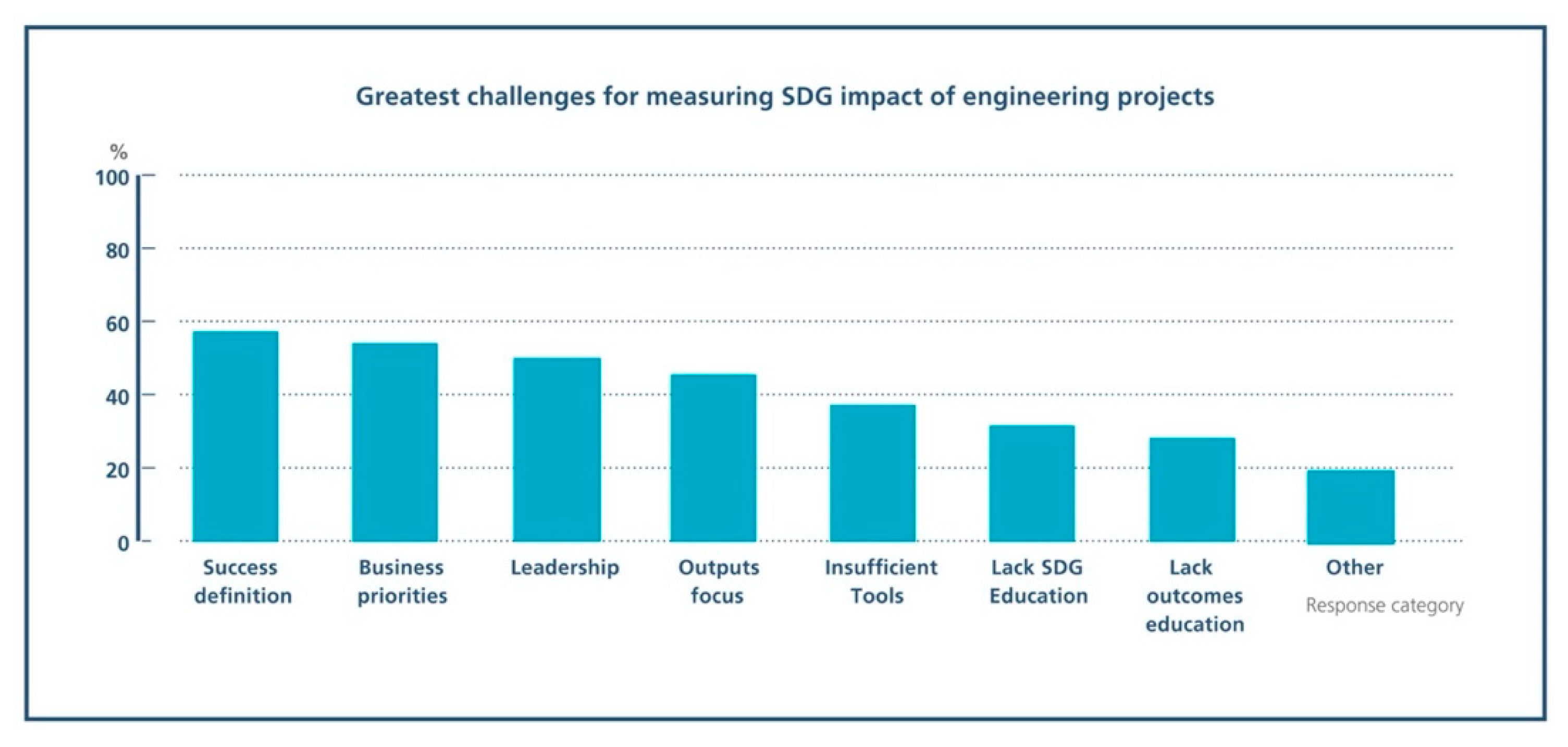

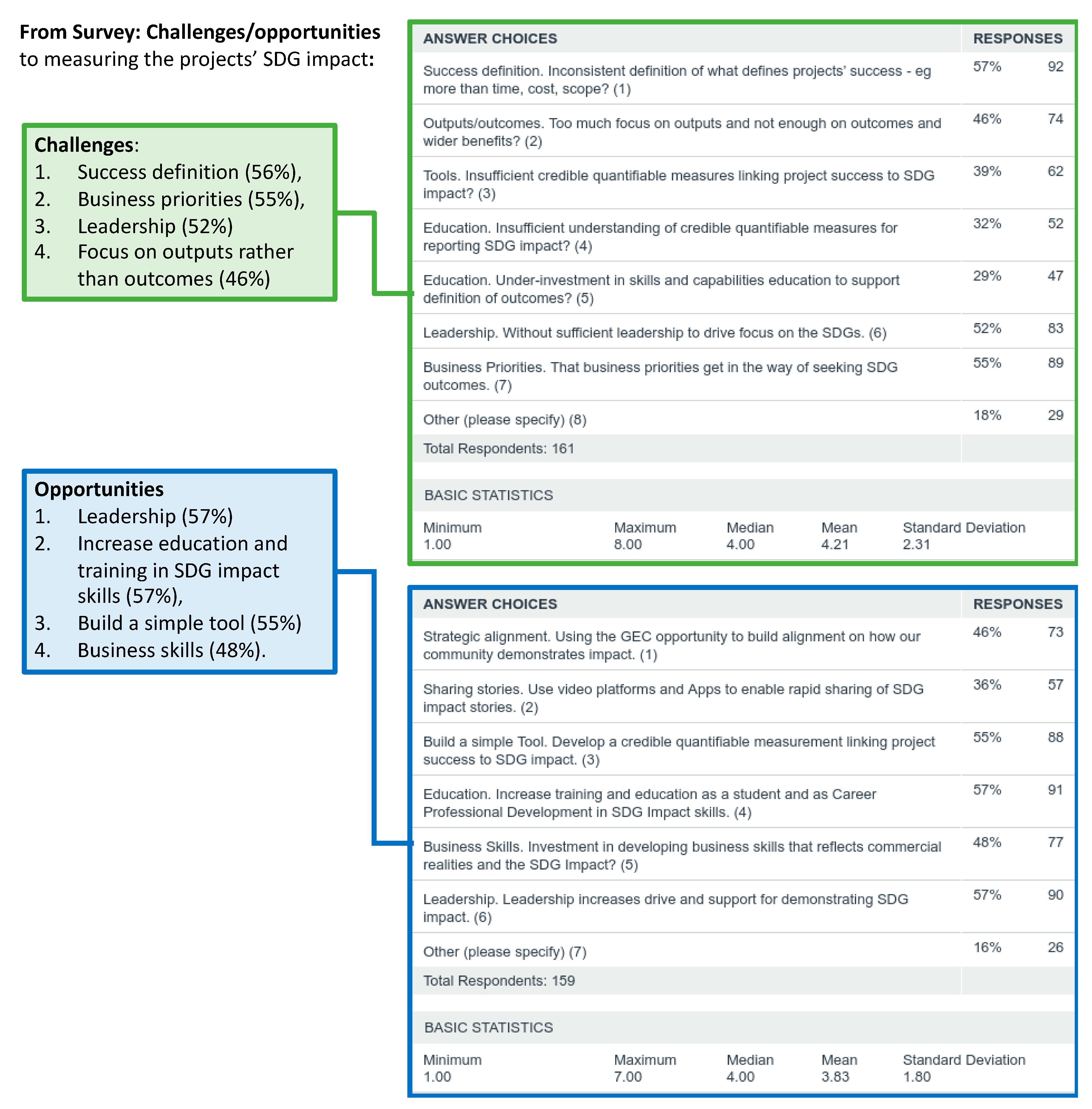

4.2.6. Question 6 (Context): What Are the Greatest Challenges for Measuring SDG Impact?

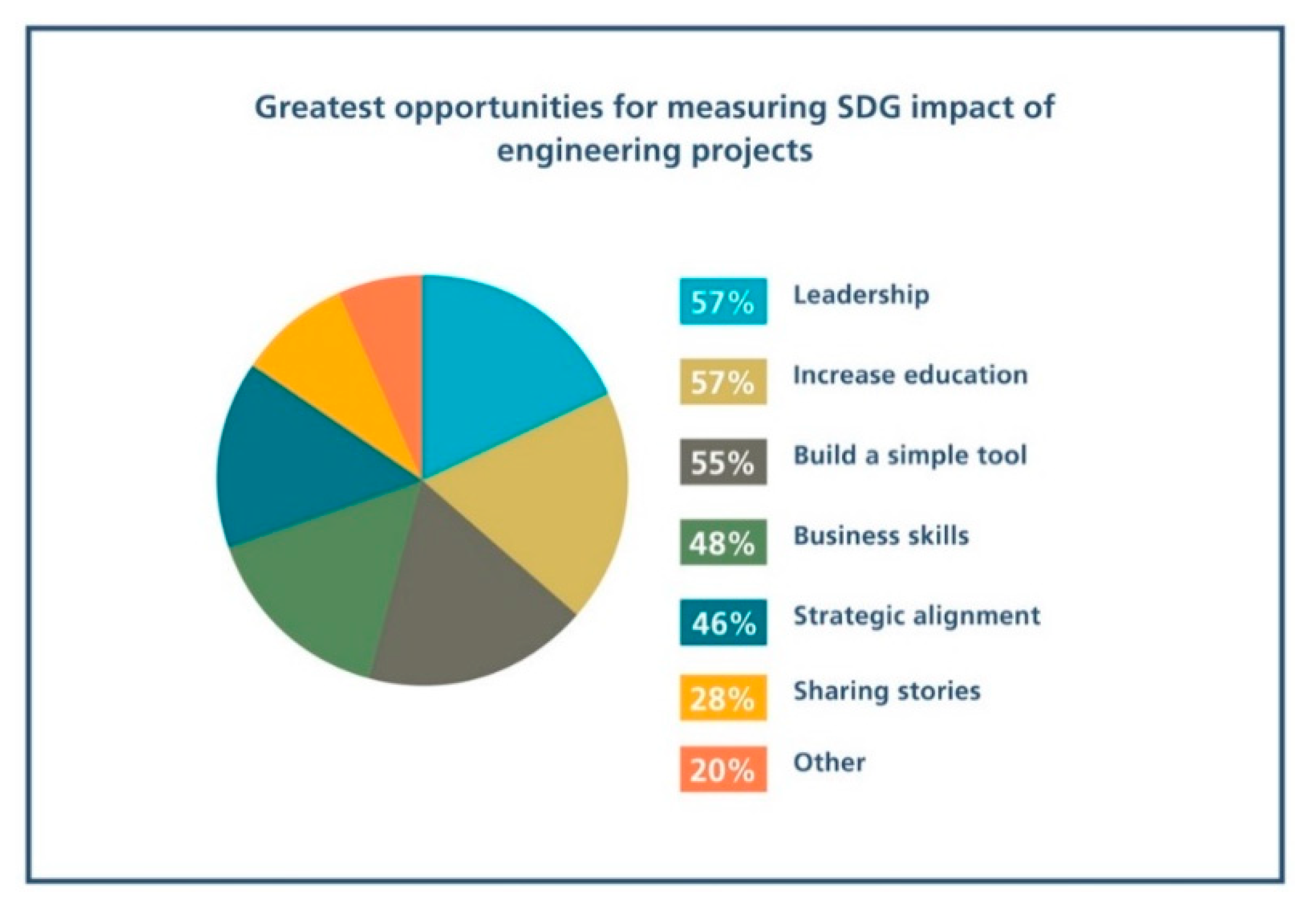

4.2.7. Question 7 (Context): How Could the Achievement of the SDGs on Future Infrastructure Projects Be Improved?

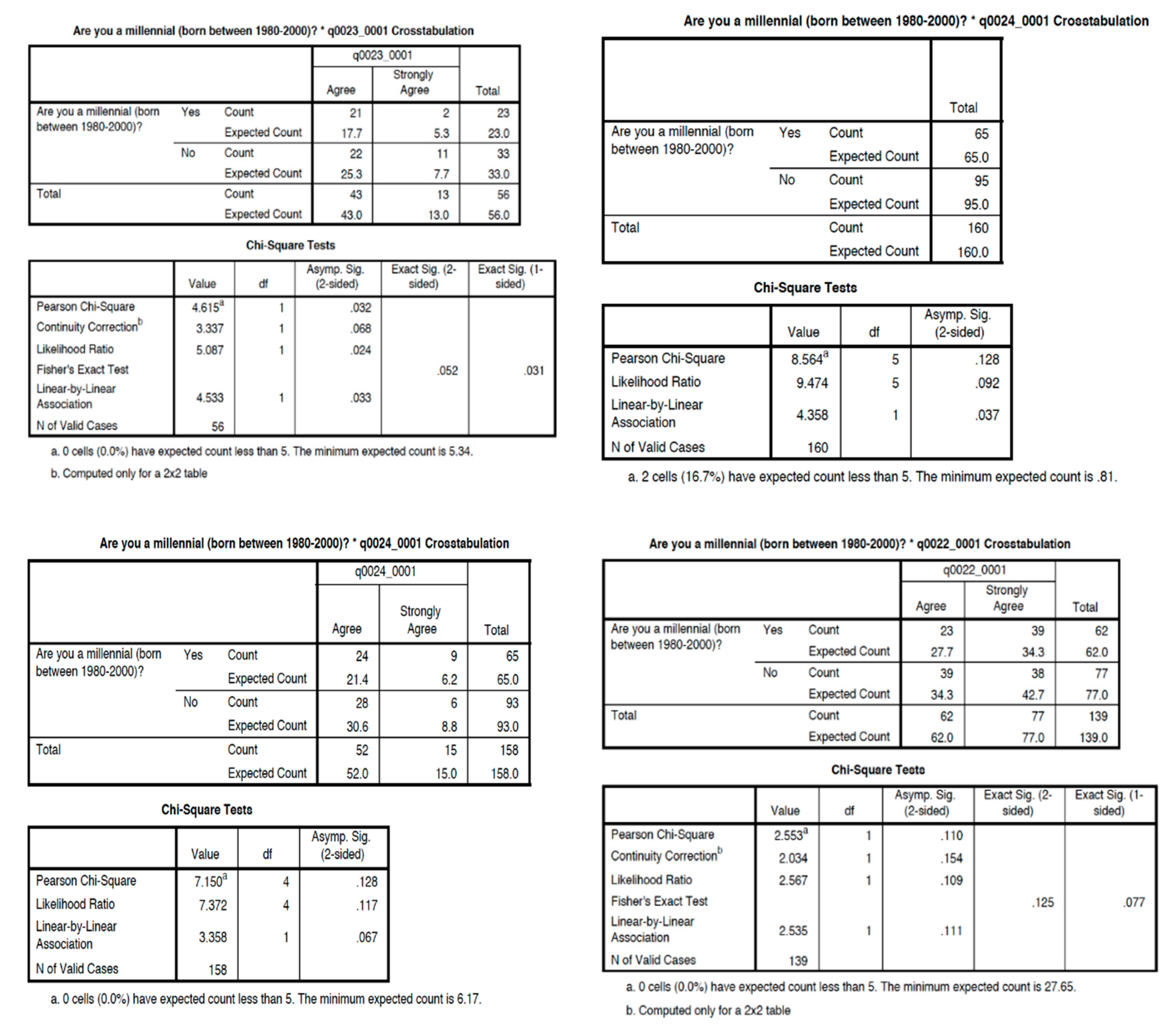

4.3. Inferential Statistics

5. Discussion, Framework Development and Policy Implications

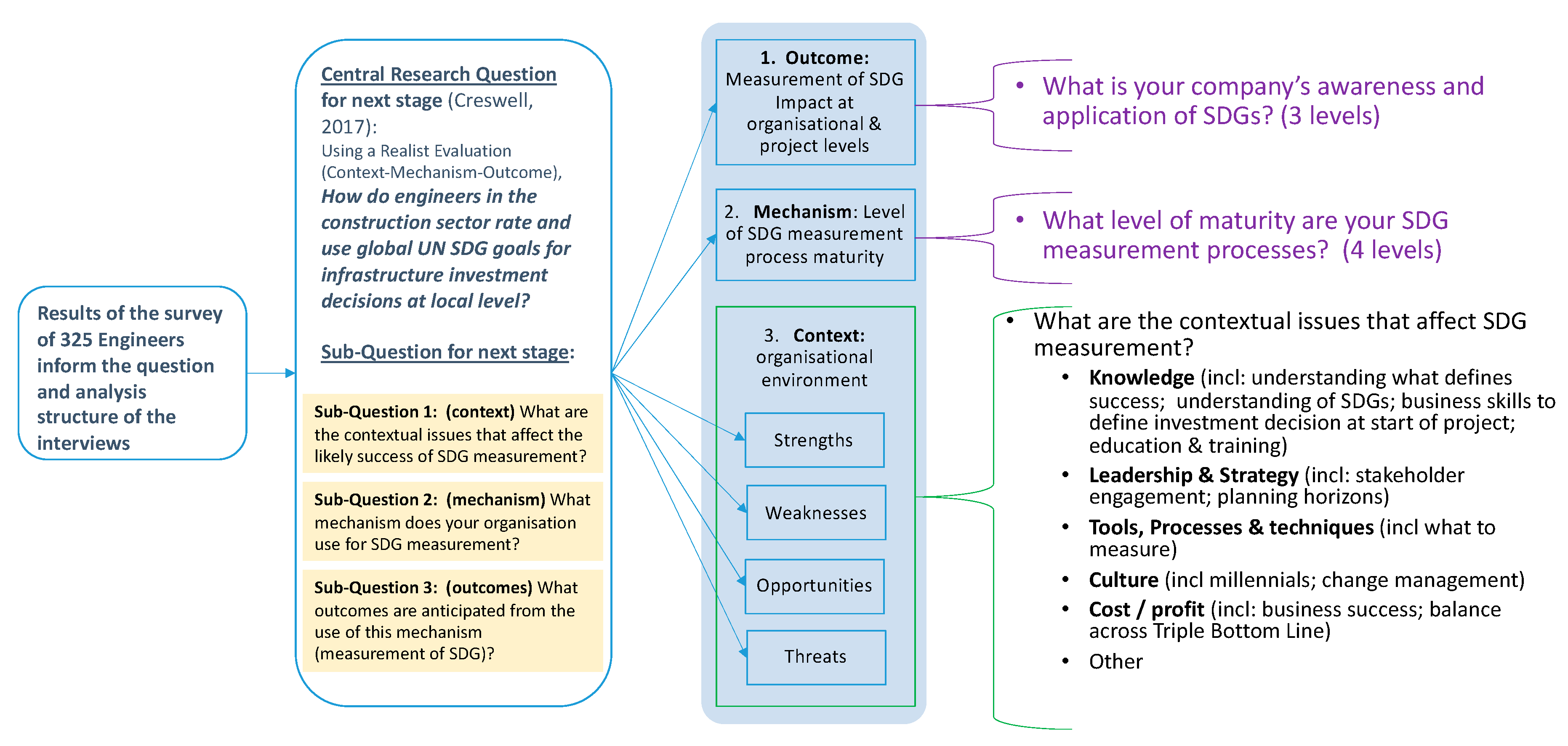

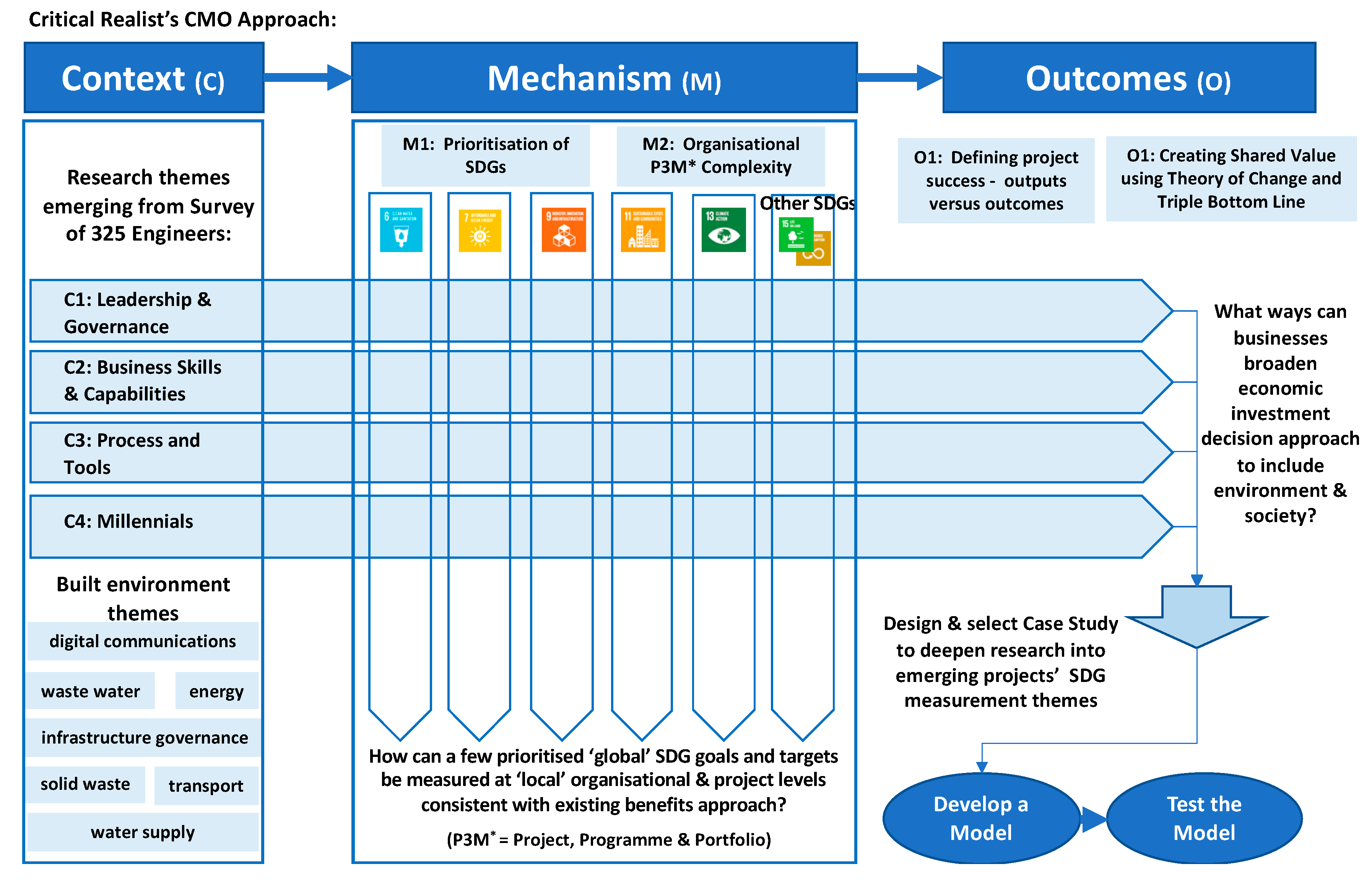

5.1. Analysis of Results and Development of a Future Research Model

5.2. Context

5.2.1. Leadership—Governance (C1)

5.2.2. Business Skills for Engineers (C2)

5.2.3. Measurement Tools and Processes (Methodologies) (C3)

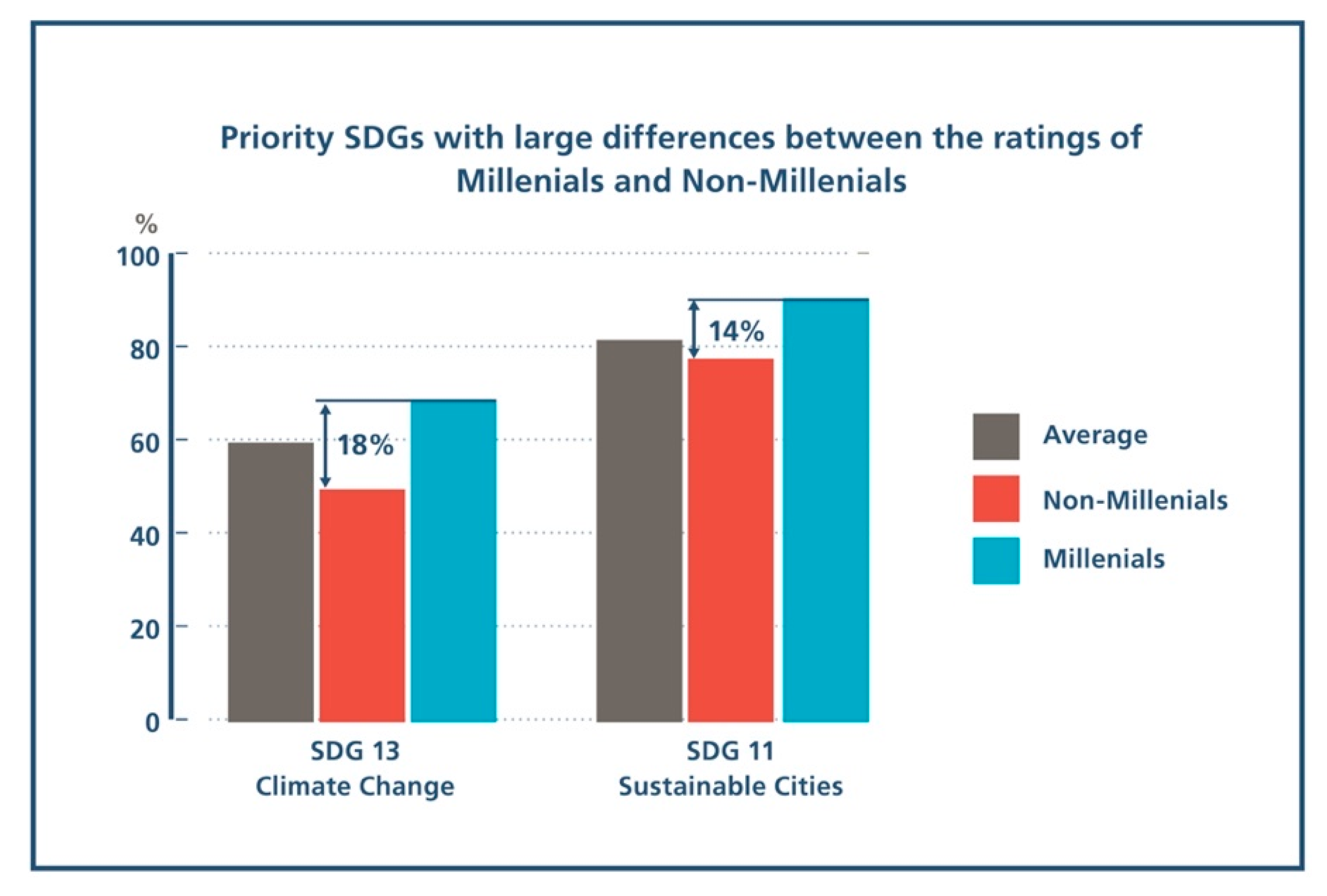

5.2.4. Millennials (C4)

5.3. Mechanism

5.3.1. Prioritisation of SDGs (M1)

5.3.2. Organisational, Portfolio, Programme and Project (P3M) Complexity (M2)

5.4. Outcomes

5.4.1. Defining Success—Outputs Versus Outcome (O1)

5.4.2. Creating Shared Value using Theory of Change and Triple Bottom Line (O2)

5.5. Development of Conceptual Framework for Measuring the SDG Performance of Infrastructure Projects

5.6. Policy Implications

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

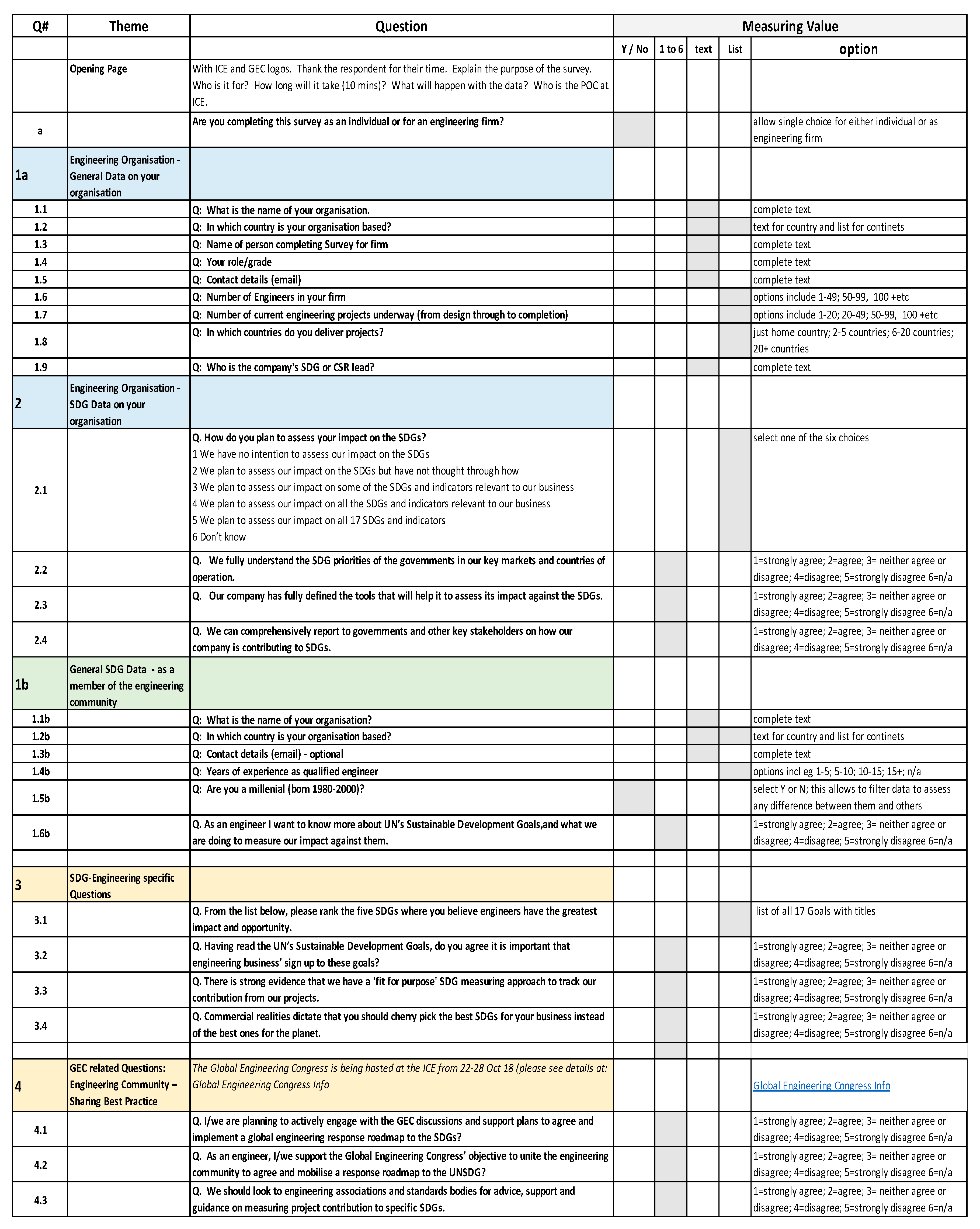

Appendix A. Survey Questions and Selection of the Type of Question and Metric to Align with Analysis Requirements for Measuring Engineers’ Views on Projects’ SDG Impact

Appendix B. Data Capture from Survey: Select the Six SDGs That You Believe That Engineers Have the Greatest Impact and Opportunity

Appendix C. Data Capture from the Survey’s Chi-Square Tests (with Continuity Correction, Likelihood Ratio, and Linear-by-Linear Association)

References

- Adshead, Daniel, Scott Thacker, Lena I. Fuldauer, and Jim W. Hall. 2019. Delivering on the Sustainable Development Goals through long-term infrastructure planning. Global Environmental Change 59: 101975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, Rui, Yrjö Koskinen, and Chendi Zhang. 2019. Corporate social responsibility and firm risk: Theory and empirical evidence. Management Science 65: 4451–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C., G. Metternicht, and T. Wiedmann. 2016. National pathways to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): A comparative review of scenario modelling tools. Environmental Science & Policy 66: 199–207. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, C., G. Metternicht, and T. Wiedmann. 2019. Prioritising SDG targets: Assessing baselines, gaps and interlinkages. Sustainability Science 14: 421–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armanios, D. E., C. E. Eesley, J. Li, and K. M. Eisenhardt. 2017. How entrepreneurs leverage institutional intermediaries in emerging economies to acquire public resources. Strategic Management Journal 38: 1373–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association for Project Management, UK. 2019. APM Body of Knowledge. Princes Risborough: Buckinghamshire. ISBN 978-1-903494-83-7. [Google Scholar]

- Astbury, B., and F.L. Leeuw. 2010. Unpacking black boxes: Mechanisms and theory building in evaluation. American Journal of Evaluation 31: 363–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, C. H. 2015. Myths, exaggerations and uncomfortable truths: The real story behind Millennials in the workplace. The IBM Institute for Business Value. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/downloads/cas/Q3ZVGRLP (accessed on 7 August 2020).

- Bali Swain, R., and F. Yang-Wallentin. 2020. Achieving sustainable development goals: Predicaments and strategies. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology 27: 96–106. [Google Scholar]

- Bénabou, R., and J. Tirole. 2010. Individual and corporate social responsibility. Economica 77: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berge, M. S. 2017. Telecare–where, when, why and for whom does it work? A realist evaluation of a Norwegian project. Journal of Rehabilitation and Assistive Technologies Engineering 4: 2055668317693737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, Dave A., and Isabelle Gaboury. 2020. Challenges related to the analytical process in realist evaluation and latest developments on the use of NVivo from a realist perspective. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 23: 355–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, Roy. 2013. A Realist Theory of Science. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, A., J. Oppenheim, and N. Stern. 2015. Driving Sustainable Development Through better Infrastructure: Key Elements of a Transformation Program. Brookings Global Working Paper Series; Washington: Brookings Institution. Available online: https://g24.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Driving-Sustainable-Development-Through-Better-Infrastructure-Key-Elements-of-a-Transformation-Program-Bhattacharya-Oppenheim-Stern-July-2015.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Bielenberg, A., M. Kerlin, J. Oppenheim, and M. Roberts. 2016. Financing change: How to mobilize private-sector financing for sustainable infrastructure. McKinsey Center for Business and Environment. [Google Scholar]

- Bonini, S., and J. Emerson. 2005. Maximizing Blended Value–Building Beyond the Blended Value Map to Sustainable Investing, Philanthropy and Organizations. Available online: http://community-wealth.org (accessed on 2 April 2020).

- Boswell, James F., David R. Kraus, Scott D. Miller, and Michael J. Lambert. 2015. Implementing routine outcome monitoring in clinical practice: Benefits, challenges, and solutions. Psychotherapy Research 25: 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brundtland, G. H. 1987. Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bugg-Levine, Antony, and Jed Emerson. 2011. Impact investing: Transforming how we make money while making a difference. Innovations: Technology. Governance, Globalization 6: 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constanza, R., L. Fioramonti, and I. Kubiszewski. 2016. The UN sustainable development goals and the dynamics of well-being. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 14: 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke-Davies, Terry. 2007. The real success factors on programmes. International Journal of Programme Management 20: 185–90. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, John W., and J. David Creswell. 2017. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Crosthwaite, C., L. Jolly, L. Brodie, L. Kavanagh, L. Buys, and J. Turner. 2012. Curriculum design and higher order skills: Challenging assumptions. Paper presented at 5th International Conference: Innovation, Practice and Research in Engineering Education (EE 2012), Coventry, UK, September 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Deloitte. 2018a. The Business Case for Inclusive Growth. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/global/Documents/About-Deloitte/gx-abt-wef-business-case-inclusive-growth-global%20report.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2020).

- Deloitte. 2018b. The Deloitte Millennial Survey 2018—Millennials’ Confidence in Business, Loyalty to Employers Deteriorate. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/global/Documents/About-Deloitte/gx-2018-millennial-survey-report.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2020).

- Diekhoff, George. 1992. Statistics for the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Univariante, Bivariate, Multivariante. No. HA29. D46 1992. London: William C Brown Pub, ISBN-10: 0697285146. ISBN-13: 978-0697285140. [Google Scholar]

- Donohue, I., H. Hillebrand, J. M. Montoya, O. L. Petchey, S. L. Pimm, M. S. Fowler, and N. E. O’Connor. 2016. Navigating the complexity of ecological stability. Ecology Letters 19: 1172–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easton, Geoff. 2010. Critical realism in case study research. Industrial Marketing Management 39: 118–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, Robert G., and Michael P. Krzus. 2010. One Report: Integrated Reporting for a Sustainable Strategy. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, John. 1994. Towards the sustainable corporation: Win-win-win business strategies for sustainable development. California Management Review 36: 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. 2018. 25 Years Ago I Coined the Phrase Triple Bottom Line. Here’s Why It’s Time to Rethink It. Harvard Business Review, June 25. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, Jed, Jay Wachowicz, and Suzi Chun. 2000. Social return on investment: Exploring aspects of value creation in the non-profit sector. The Box Set: Social Purpose Enterprises and Venture Philanthropy in the New Millennium 2: 130–73. [Google Scholar]

- Forum for the Future. 2018. Our Net Positive Approach. Available online: https://www.forumforthefuture.org/net-positive (accessed on 2 April 2020).

- Fukuda-Parr, S., and D. McNeill. 2019. Knowledge and Politics in Setting and Measuring the SDG s: Introduction to Special Issue. Global Policy 10: 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullan, M. 2005. Leadership & Sustainability: System Thinkers in Action. Thousand Oaks: Corwin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Galli, Alessandro, Gordana Đurović, Laurel Hanscom, and Jelena Knežević. 2018. Think globally, act locally: Implementing the sustainable development goals in Montenegro. Environmental Science & Policy 84: 159–69. [Google Scholar]

- Global Infrastructure Hub. 2019. Infrastructure Investment need in the Compact with African Countries. Available online: https://outlook.gihub.org/?utm_source=GIHub+Homepage&utm_medium=Project+tile&utm_campaign=Outlook+GIHub+Tile (accessed on 6 June 2020).

- Global Reporting Initiative. 2015. SDG Compass–The Guide for Business Action on the SDGs. SDG Compass. Available online: https://sdgcompass.org/ (accessed on 11 August 2020).

- Global Reporting Initiative. 2016. Carrots and Sticks, Global Trends in Sustainability Reporting Regulation and Policy’. Available online: https://www.carrotsandsticks.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Carrots-Sticks-2016.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Greenhalgh, Trisha, Charlotte Humphrey, Jane Hughes, Fraser Macfarlane, Ceri Butler, and Ray Pawson. 2009. How do you modernize a health service? A realist evaluation of whole-scale transformation in London. The Milbank Quarterly 87: 391–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griggs, D., M. Stafford-Smith, O. Gaffney, J. Rockström, M. C. Öhman, P. Shyamsundar, W. Steffen, G. Glaser, N. Kanie, and I. Noble. 2013. Policy: Sustainable development goals for people and planet. Nature 495: 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hak, T., S. Janoušková, and B. Moldan. 2016. Sustainable Development Goals: A need for relevant indicators. Ecological Indicators 60: 565–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J. W., M. Tran, A. J. Hickford, and R. J. Nicholls. 2016. The Future of National Infrastructure: A System of Systems Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hayward, R., J. Lee, J. Keeble, R. McNamara, C. Hall, S. Cruse, P. Gupta, and E. Robinson. 2013. The UN global compact-accenture CEO study on sustainability 2013. UN Global Compact Reports 5: 1–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, E., K. Linnerud, and D. Banister. 2017. The imperatives of sustainable development. Sustainable Development 25: 213–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horrocks, Ivan, and Leslie Budd. 2015. Into the void: A realist evaluation of the eGovernment for You (EGOV4U) project. Evaluation 21: 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, Neil, and William Strauss. 1991. Generations: The History of America’s Future, 1584 to 2069. New York: William Morrow & Company, p. 538. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, G. 2009. Measuring organizational performance: Beyond the triple bottom line. Business Strategy and the Environment 18: 177–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institution of Civil Engineers. 2018. Project 13 Blueprint and Commercial Handbook. London: Institution of Civil Engineers. Available online: http://www.p13.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/P13-Blueprint-Web.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2020).

- IPCC. 2018. Global Warming of 1.5 °C, an IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C Above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty. Geneva: IPCC. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, P., and D. Comfort. 2020. A commentary on the localisation of the sustainable development goals. Journal of Public Affairs 20: e1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, A., and R. L. Paquin. 2016. The triple layered business model canvas: A tool to design more sustainable business models. Journal of Cleaner Production 135: 1474–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R. S., and D. P. Norton. 1996. Using the Balanced Scorecard as a Strategic Management System. Boston: Harvard Business School. [Google Scholar]

- Klopp, J. M., and D. L. Petretta. 2017. The urban sustainable development goal: Indicators, complexity and the politics of measuring cities. Cities 63: 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labor, U. D. 2017. US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2017/home.htm (accessed on 7 August 2020).

- Lenth, Russell V. 2001. Some practical guidelines for effective sample size determination. The American Statistician 55: 187–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S. S., K. Allen, Z. A. Bhutta, L. Dandona, M. H. Forouzanfar, N. Fullman, P. W. Gething, E. M. Goldberg, S. I. Hay, M. Holmberg, and et al. 2016. Measuring the health-related Sustainable Development Goals in 188 countries: A baseline analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet 388: 1813–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linsley, Paul, David Howard, and Sara Owen. 2015. The construction of context-mechanisms-outcomes in realistic evaluation. Nurse Researcher 22: 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhi, Yadvinder, Luiz Eduardo O. C. Aragão, Daniel B. Metcalfe, Romilda Paiva, Carlos A. Quesada, Samuel Almeida, Liana Anderson, Paulo Brando, Jeffrey Q. Chambers, Antonio C. L. Da Costa, and et al. 2009. Comprehensive assessment of carbon productivity, allocation and storage in three Amazonian forests. Global Change Biology 15: 1255–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, M. L., and M. M. Carvalho. 2016. Sustainability and success variables in the project management context: An expert panel. Project Management Journal 47: 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merry, Sally Engle. 2019. The Sustainable Development Goals Confront the Infrastructure of Measurement. Global Policy 10: 146–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, Louise, and Sue Benn. 2013. Leadership for sustainability: An evolution of leadership ability. Journal of Business Ethics 112: 369–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micheli, Pietro, and Jean-Francois Manzoni. 2010. Strategic performance measurement: Benefits, limitations and paradoxes. Long Range Planning 43: 465–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, Ross, and Kelly Hall. 2013. Social return on investment (SROI) and performance measurement: The opportunities and barriers for social enterprises in health and social care. Public Management Review 15: 923–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, Peter. 2013. Reconstructing Programme Management. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, Peter. W. G. 2017. Climate Change and What the Project Management Profession Should Be Doing about It. Princes Risborough, Buckinghamshire: Association for Project Management. Available online: https://www.apm.org.uk/media/7496/climate-change-report.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2020).

- Morse, S. 2013. Indices and Indicators in Development: An Unhealthy Obsession with Numbers. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Nardi, P. M. 2015. Doing Survey Research. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- National Audit Office. 2005. Improving Public Services through better Construction. Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General HC 364-I Session 2004–2005. London: TSO. [Google Scholar]

- Nerini, F. F., J. Tomei, L. S. To, I. Bisaga, P. Parikh, M. Black, A. Borrion, C. Spataru, V. C. Broto, G. Anandarajah, and et al. 2018. Mapping synergies and trade-offs between energy and the Sustainable Development Goals. Nature Energy 3: 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New Climate Economy. 2016. The Global Commission on the Economy and Climate. Washington: World Resources Institute. Available online: https://www.deutsches-klima-konsortium.de/fileadmin/user_upload/pdfs/Briefings/Morgan_12_Nov_15.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Office of National Statistics. 2019. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment-uk.github.io/reporting-status/ (accessed on 6 June 2020).

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. 2015. G20/OECD Principles of Corporate Governance. Paris. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/governance/g20-oecd-principles-of-corporate-governance-2015_9789264236882-en (accessed on 6 June 2020).

- Økland, A. 2015. Gap analysis for incorporating sustainability in project management. Procedia Computer Science 64: 103–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, Zarina, Saskia Greyling, David Simon, Helen Arfvidsson, Nishendra Moodley, Natasha Primo, and Carol Wright. 2017. Local responses to global sustainability agendas: Learning from experimenting with the urban sustainable development goal in Cape Town. Sustainability Science 12: 785–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawson, R., and N. Tilley. 1997. An introduction to scientific realist evaluation. In Evaluation for the 21st Century: A Handbook. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, pp. 405–18. [Google Scholar]

- Pawson, R., T. Greenhalgh, G. Harvey, and K. Walshe. 2005. Realist review-a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 10 Suppl. 1: 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Perrini, F., and A. Tencati. 2006. Sustainability and stakeholder management: The need for new corporate performance evaluation and reporting systems. Business Strategy and the Environment 15: 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, L. D., A. D. Pressey, M. Vanharanta, and W. J. Johnston. 2013. Constructivism and critical realism as alternative approaches to the study of business networks: Convergences and divergences in theory and in research practice. Industrial Marketing Management 42: 336–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirier, E., D. Forgues, and S. Staub-French. 2016. Collaboration through innovation: Implications for expertise in the AEC sector. Construction Management and Economics 34: 769–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. E., and M. R. Kramer. 2011. The Big Idea: Creating Shared Value, Rethinking Capitalism. Harvard Business Review, 89. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, R., C. Dovrolis, M. Murray, and K. C. Claffy. 2003. Bandwidth estimation: Metrics, measurement techniques, and tools. IEEE Network 17: 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, Felix. 2012. A Global Redesign?: Shaping the Circular Economy. London: Chatham House. [Google Scholar]

- Price Waterhouse Coopers. 2018. From Promise to Reality: Does Business Really Care about the SDGs? London: PwC. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/sustainability/SDG/sdg-reporting-2018.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Proctor, Enola, Hiie Silmere, Ramesh Raghavan, Peter Hovmand, Greg Aarons, Alicia Bunger, Richard Griffey, and Melissa Hensley. 2011. Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 38: 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainey, Hugo J., Edward H. B. Pollard, Guy Dutson, Jonathan M. M. Ekstrom, Suzanne R. Livingstone, Helen J. Temple, and John D. Pilgrim. 2015. A review of corporate goals of No Net Loss and Net Positive Impact on biodiversity. Oryx 49: 232–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, J. C. 2001. Rising Life Expectancy: A Global History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rockström, J., W. Steffen, K. Noone, Å. Persson, F. S. Chapin, III, E. Lambin, T. M. Lenton, M. Scheffer, C. Folke, H. J. Schellnhuber, and et al. 2009. Planetary boundaries: Exploring the safe operating space for humanity. Ecology and Society, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, Jeffrey D. 2012. From millennium development goals to sustainable development goals. The Lancet 379: 2206–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J. D., G. Schmidt-Traub, and D. Durand-Delacre. 2016. Preliminary sustainable development goal (SDG) index and dashboard. Sustainable Development Solutions Network, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Sawaf, Ayman, and Rowan Gabrielle. 2014. Sacred Commerce: A Blueprint for a New Humanity, 2nd ed. Sherman Oaks: EQ Enterprises, pp. 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sayer, R. A. 1992. Method in Social Science: A Realist Approach. East Sussex: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schaltegger, Stefan, and Roger Burritt. 2000. Contemporary Environmental Accounting: Issues, Concepts and Practice. Sheffield: Greenleaf Publishing, p. 111. [Google Scholar]

- Scheyvens, Regina, Glenn Banks, and Emma Hughes. 2016. The private sector and the SDGs: The need to move beyond ‘business as usual’. Sustainable Development 24: 371–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvius, A. J., and R. P. Schipper. 2014. Sustainability in project management: A literature review and impact analysis. Social Business 4: 63–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvius, A. G., M. Kampinga, S. Paniagua, and H. Mooi. 2017. Considering sustainability in project management decision making; An investigation using Q-methodology. International Journal of Project Management 35: 1133–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, R. A., and B. C. Straits. 2010. Approaches to Social Research. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sosik, John J., and Dongil Jung. 2018. Full Range Leadership Development: Pathways for People, Profit, and Planet. London and New Tork: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Steffen, Will, Katherine Richardson, Johan Rockström, Sarah E. Cornell, Ingo Fetzer, Elena M. Bennett, Reinette Biggs, Stephen R. Carpenter, Wim De Vries, Cynthia A. De Wit, and et al. 2015. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 347: 1259855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, D., and C. Valters. 2012. Understanding Theory of Change in International Development. Available online: http://www.theoryofchange.org/wp-content/uploads/toco_library/pdf/UNDERSTANDINGTHEORYOFChangeSteinValtersPN.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2020).

- Suess, Erwin. 1980. Particulate organic carbon flux in the oceans—Surface productivity and oxygen utilization. Nature 288: 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, Ranjula Bali. 2018. A Critical Analysis of the Sustainable Development Goals. In Handbook of Sustainability Science and Research. Edited by Leal Filho W. World Sustainability Series. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Tansey, Oisín. 2007. Process tracing and elite interviewing: A case for non-probability sampling. PS: Political Science and Politics 40: 765–72. [Google Scholar]

- Thacker, S., and J. Hall. 2018. Engineering for Sustainable Development. Oxford: Infrastructure Transition Research Consortium (ITRC), University of Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Thacker, Scott, Daniel Adshead, Marianne Fay, Stéphane Hallegatte, Mark Harvey, Hendrik Meller, Nicholas O’Regan, Julie Rozenberg, Graham Watkins, and Jim W. Hall. 2019. Infrastructure for sustainable development. Nature Sustainability 2: 324–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Themistocleous, G., and S. H. Wearne. 2000. Project management topic coverage in journals. International Journal of Project Management 18: 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiry, M. 2004. Value Management. In Wiley Guide to Managing Projects. Edited by P. Morris and J. Pinto. Holbroken: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Tilley, Nick. 2016. EMMIE and engineering: What works as evidence to improve decisions? Evaluation 22: 304–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilt, B. 2009. The Struggle for Sustainability in Rural China: Environmental Values and Civil Society. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- UK’s Infrastructure and Projects Authority. 2020. The 2020 Annual Report on the Government Major Projects Portfolio. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/infrastructure-and-projects-authority-annual-report-2020 (accessed on 6 August 2020).

- United Nations. 2015. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly. New York: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. 2018. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2018. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/files/report/2018/TheSustainableDevelopmentGoalsReport2018-EN.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2019).

- US Public Interest Research Group. 2016. Available online: https://uspirg.org/reports/usp/millennials-motion (accessed on 2 April 2020).

- Weiss, C. H. 1995. Nothing as Practical as Good Theory: Exploring Theory-Based Evaluation for Comprehensive Community Initiatives for Children and Families. New Approaches to Evaluating Community Initiatives: Concepts, Methods, and Contexts 1: 65–92. [Google Scholar]

- Yamey, Basil S. 1949. Scientific bookkeeping and the rise of capitalism. The Economic History Review 1: 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachariadis, Markos, Susan Scott, and Michael Barrett. 2013. Methodological implications of critical realism for mixed-methods research. MIS Quarterly 2013: 855–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, Shaker A., Harry J. Sapienza, and Per Davidsson. 2006. Entrepreneurship and dynamic capabilities: A review, model and research agenda. Journal of Management Studies 43: 917–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| # | C–M–O Configuration Reference | How Might the Insights Inform Engineering Project SDG Measurement Analysis? |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Terminology. Pawson and Tilley’s Realistic Evaluation (Pawson and Tilley 1997) is widely held as the originators of the Realist Evaluation CMO configuration. | Through understanding the origins of the C–M–O approach and its terminology, research into engineering projects can build on established protocols and use their approach to widen our understanding of its employability outside the clinical and educational sectors, where they are most frequently used. |

| 2 | Projects application. Pawson and Tilley’s Realistic Evaluation (Pawson and Tilley 1997) | Pawson and Tilley suggest that the value of the C–M–O strategy is that it enables the researcher to better analyse the nature of programmes and projects and, more importantly, how they work. Thus, the core element of the realist approach is to provide a new perspective on how intervention using a mechanism brings about outcomes that represent change. Engineering-based research can thus adopt Pawson and Tilley’s approach to better understand and explore the mechanism of change in order to evaluate a project or programme. |

| 3 | Engineering application.Tilley (2016) developed the C–M–O model to assess how it can be used by engineers to improve their decision making for policy and project decisions. | As a proponent of realism, Tilley argues for a pragmatic approach in engineering to be adopted for its evaluations. The research adapts the C–M–O model to the EMMIEI approach that includes Effects, Mechanism, Moderator (or context), Implementation and Economic Impact. Importantly, the differences between engineering physical worlds and the social world are recognised, but it is suggested that both benefit from a pragmatic research strategy. This is helpful for the measurement of SDGs because it gives confidence of relevance to the engineering domain of using the C–M–O configuration. |

| 4 | Engineering application.Horrocks and Budd (2015) used the C–M–O structure to evaluate a European e-services systems engineering project to establish the outcomes and understand the why, for whom, and how? | The project evaluation of ‘e-government for You’ used the theory-driven evaluation approach based on the C–M–O model to enhance the focus and granularity for their study. This supports the usage of the C–M–O model for SDG measurement because it allows for the mixed-method approach and structures the analysis framework in a readily understood causal chain. |

| 5 | Construction project application.Peters et al. (2013) examined Critical Realism evaluation models to study business networks. They used a UK construction project to explore the managerial phenomenon, specifically the practice of novation in temporary organisational networks. | The origins of the C–M–O model are from the Critical Realism traditions, and therefore, the Peters et al. (2013) article provides a useful insight into the approach that a strongly theoretical lens can use when applied to the ground level of a local construction project. This helps shape the SDG approach by giving confidence that the ‘realistic learning’ from the Peters study can be replicated for SDGs. |

| 6 | Construction project application.Poirier et al. (2016) evaluated the use of a Critical Realism lens to assess the delivery of building projects in the architecture, engineering and construction (AEC) sector. They evaluated how collaboration can improve performance and value across five core entities, namely process, structures, agents, artefacts and context. | There are strong parallels of the study into the AEC’s value derived from collaboration in project delivery. The relevance to the C–M–O approach is that they both derive from the critical realism tradition and seek to understand causal patterns and assess what are the outcomes of employing a specific mechanism within a given context. In particular, the study highlights how the learnings can be structured in a way that is most readily understood by practitioners in an area of great complexity. |

| 7 | Multi-sector application. Although Bergeron and Gaboury (2020) come from a clinical care perspective, their recent study highlights some of the challenges of using the C–M–O framework that has relevance to all disciplines and sectors that use its causal framework. Further challenges were also identified in the article described below, by Crosthwaite. | There are a number of methodological challenges that are identified and should be noted by engineering researchers using this approach. Solutions to the analytic difficulties are shared that can help the identification of patterns and assist the researcher to maintain transparency in the analytical process, thus strengthening the ability to make generalisations. |

| 8 | Education application.Crosthwaite et al. (2012) used the C–M–O approach to understand the educational impacts of the ‘Engineers without Borders’ in Australia and New Zealand. | While not focused on an engineering project, this article highlights the use of the model in the education sector to evaluate the causal impact based on the identification of specific issues within the C–M–O framework. In regard to the SDG approach, there is value in combining the qualitative and quantitative approaches to improve the understand the observed outcomes. |

| 9 | Health system application.Greenhalgh et al. (2009) used the C–M–O method to evaluate a health system. This wide-ranging analysis of a systems transformation environment sought to understand the reasons for how and why the outcomes were achieved. | The broad nature of evaluating organisational systemic transformation has similarities of complexity with research into the measurement of SDG impacts at project and organisational level. The simpler C–M–O approach offers a means to help explain causal effects more simply, and this has benefits for both research and practitioners. |

| 10 | Projects application.Berge (2017) used a realist evaluation approach on a Norwegian telecare project. While the study has a clinical orientation, its project approach is instructive. | Realist evaluation is used to scrutinize what it is about the telecare system that works for whom, why, how, and in which circumstances. The study provides a more nuanced approach. |

| Survey Design and Analysis Methods | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Problem specification and Research Question | As captured in the introduction paragraph of this paper; formulation of problem and objectives. |

| 2 | Population Definition | With support from the Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE); seeking a representative sample from across the engineering community. |

| 3 | Selection of Mode | Use of Survey Monkey © software tool—for design and running of survey data collection. It also provided statistical analysis, supported by SPSS. |

| 4 | Design Instrument | Identify types of questions aligned to the Realist Evaluation C–M–O approach; draft of the expected results to assess whether the design would achieve the outcomes; draft the questions on Likert scale; use closed and open questions selectively; test the approach with experts. |

| 5 | Specify and Test Procedure | Build the logic framework in the tool and run a pilot to test the success. |

| 6 | Data Collection | ICE distributes the survey to 1500 of its members; 325 complete the survey, ca. 20% response rate, providing representative sample. |

| 7 | Analysis | Analysis completed in four stages of diagnostic analysis: Stage 1: Download all data (quantitative and qualitative) in MS ExcelTM; remove erroneous and false data, e.g., delete test data from the pilot. Structure data for analysis—e.g., charts and graphs to visualize data. Stage 2: Use software tool on survey monkey and SPSS to analyse the data’s statistical significance; identify patterns and gaps/overlaps against research question’s objectives. Stage 3: Analyse data touch points (using C–M–O coding) and correlate findings to the original research question and the C–M–O model. Complete initial write-up for review. Stage 4: Share data findings with expert panel (of 12 qualified engineers) organised by the ICE; test the findings; keep integrity of the data but use expert panel to assess the implications and possible next steps. For example, the panel suggested that the low level of organisational responses could be addressed in the interview stage of the research. (Note: The three separate workshops were recorded, but they have not been included in this article.) |

| 8 | Reporting | Step 1: Build the data charts that illustrate the findings. Step 2: Write up the findings: test and adjust to ensure recommendations and conclusions are consistent with original research question; identify lessons and insights that inform the next stage of research—the 40 interviews. |

| C–M–O Future Research Focus | Assumptions Derived from Stage 1 Research | Supporting Literature | Questions for Next Stage of Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prioritisation of SDGs (M1) | Assumptions:

| (Klopp and Petretta 2017; Donohue et al. 2016; Nerini et al. 2018; Allen et al. 2016; IPCC 2018; Swain 2018; UN 2018; Hall et al. 2016; Martens and Carvalho 2016) | Q1: How can a simplified selection of goals and targets be identified at organisational and project levels? |

| Organisational P3M Complexity and Sustainability (M2) | Assumptions:

| (Morris 2013; Cooke-Davies 2007; Morris 2017); NAO Report Projects (National Audit Office 2005); (Silvius and Schipper 2014; Silvius et al. 2017; Martens and Carvalho 2016; Økland 2015; Silvius and Schipper 2014; APM 2019; Sawaf and Gabrielle 2014; Schaltegger and Burritt 2000; Eccles and Krzus 2010; Bonini and Emerson 2005; Bugg-Levine and Emerson 2011; Preston 2012; Malhi et al. 2009; Suess 1980; Tilt 2009; Perrini and Tencati 2006; Kaplan and Norton 1996) | Q2: Can a measurement system be designed to address different P3M levels? Q3: Can an MREL (monitoring, reporting, evaluation and learning) learning loop be established that is suitable for each of the levels from organisational level to portfolio, programme and project levels? Q4: What existing sustainability measurement systems are used at project (e.g., CEEQUAL) and organisational (e.g., Global Reporting System) levels, and how might they be used to align with SDG measurement? |

| Defining Success—Outputs Versus Outcome (O1) | Assumptions:

| Theory of Change and Logic Model: Stein and Valters 2012; Weiss 1995; Project Success: Thiry 2004; Themistocleous and Wearne 2000 | Q5: Can the existing causal value chain of the benefits approach (from project inputs through activities, outputs, outcomes and impacts) be used to build a commonly understood view of what future SDG measurement success looks like? |

| Creating Shared Value using Triple Bottom Line (O2) | Assumptions:

| Creating Shared Value: (Porter and Kramer 2011; Elkington 1994, 2018; OECD 2019; UN 2018); Triple Bottom Line: (Elkington 1994, 2018; Griggs et al. 2013) | Q6: Can the prototype model include the TBL ‘golden thread’ to establish a pathway through the project SDG measurement in a way that practitioners can use effectively and efficiently? Q7: Is the concept of CSV recognised and valued by executives, and does it offer a route to integrated SDG measurement? |

| No. | Policy Area | Research Implications Affecting Policy Design |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Harnessing the power of millennials to drive the SDG and climate change agenda. |

|

| 2 | Redefining success |

|

| 3 | Engineering organisational and project context—designing measuring mechanisms that work |

|

| 4 | MREL—Monitoring, reporting, evaluation and learning |

|

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mansell, P.; Philbin, S.P.; Konstantinou, E. Redefining the Use of Sustainable Development Goals at the Organisation and Project Levels—A Survey of Engineers. Adm. Sci. 2020, 10, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci10030055

Mansell P, Philbin SP, Konstantinou E. Redefining the Use of Sustainable Development Goals at the Organisation and Project Levels—A Survey of Engineers. Administrative Sciences. 2020; 10(3):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci10030055

Chicago/Turabian StyleMansell, Paul, Simon P. Philbin, and Efrosyni Konstantinou. 2020. "Redefining the Use of Sustainable Development Goals at the Organisation and Project Levels—A Survey of Engineers" Administrative Sciences 10, no. 3: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci10030055

APA StyleMansell, P., Philbin, S. P., & Konstantinou, E. (2020). Redefining the Use of Sustainable Development Goals at the Organisation and Project Levels—A Survey of Engineers. Administrative Sciences, 10(3), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci10030055