1. Introduction

The international competitive environment forces businesses to seek strategic advantages in non-traditional fields, such as human resources and organizational culture (

Kargas and Varoutas 2015). More and more companies are trying to avoid competition by achieving goals that cannot be easily imitated or copied. Such a goal, capable of achieving and maintaining a competitive advantage, is employer branding. While most companies use “branding” to earn customers or to promote their products/services, some of the most innovative businesses are trying to attract the most talented employees. Creating an attractive working place can lead to (a) increased working productivity, (b) strengthening of innovational character, and (c) greater competitiveness (

Haegerstrand and Knutsson 2019).

The idea that organizations’ external image is an important factor for recruiting originated in the 1990s (

Gatewood et al. 1993).

Ambler and Barrow (

1996), expanded “branding’s” concept by examining its usage not only to attract clients but also employees. Such a perspective became rather attractive and was adopted by brands and international fora. The Conference Board of Canada, for example, pointed out the importance of employer branding as a means (a) for successfully embedding a company’s values, (b) increasing employees’ satisfaction, and (c) leading companies to long-term (or sustainable) competitive advantage (

Dell et al. 2001). Soon enough a series of empirical studies (

Ritson 2002;

Davies 2008;

Gilliver 2009) supported this theoretical framework by providing evidence that strong employer branding can reduce employees’ obtaining cost, improve the relationships among staff, and increase employees’ commitment to the company.

Employer branding and its importance emerged after the millennium, when it became clear that a new business era had arisen that was mainly based on “knowledge”. Under this condition human resources became crucial for achieving operational effectiveness, while a lack of specialized employees could lead to over-competition between companies (

Ewing et al. 2002). In order to avoid such a phenomenon new tools in human resource (HR) management developed. Such tools aim to recruit the most promising business talents, while the employees’ perception of the employers’ brand becomes of high significance in the employment market (

Ewing et al. 2002). The conducted research on the role of branding and reputation in human resource management (HRM) (

Martin et al. 2005;

Russell and Brannan 2016;

Timming 2019) mainly promoted the idea that these aspects may influence key HRM processes and outcomes (

Edwards 2017;

Theurer et al. 2018). The research conducted followed the conceptualization of

Aggerholm et al. (

2011) which involves (a) branding, (b) human resource management, and (c) corporate social responsibility; the three main characteristics involved are: (1) strategic branding discipline, (2) co-created values, and (3) sustainable employer–employee relationships. The above-mentioned characteristics are the base for developing a dynamic framework in which employees become stakeholders rather than just part of the labor force.

This framework played a significant role in a series of studies that mainly concentrated on the concrete attributes of employer brands (

Edwards and Edwards 2013) and their influence on aspects, such as perceived organizational attractiveness of job-seekers and job choice intentions (

Baum and Kabst 2013;

Collins and Stevens 2002). Only recently, has there been an increased interest in employer branding’s effects on firm performance and the underlying mediating mechanisms (

Tumasjan et al. 2020).

The current research aims to study the implementation of employer branding in Greece as a tool of attracting executives in the field of telecommunications. The selection of the telecommunication sector was based on: (a) the technological background that demands fast modulation with the international competition in technological level and business operational models and (b) its role for the Greek economy and occupation in general. Moreover, the telecommunication industry has been chosen as one of the most indicative and dynamic industries (in terms of changes and new technologies usage) in the Greek economy, even under the conditions of the economic crisis.

The telecommunications market consists of four main companies—providers in fixed telephony, three of which are operating in mobile services as well. Their total income constitutes 2.8% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), with total turnover figures up to 5.5 billion euro between 2017–2018 and with equivalent investments up to one billion (

EETT 2018). The field directly occupies 22,000 employees (about 1.27% of the total workforce of Greece), while the above-mentioned numbers are increased if external technicians and virtual network providers are taken into account (

EETT 2018). Moreover, the telecommunication industry is a leading sector as far as it concerns operational changes, driving a large part of the whole economy towards a developmental direction (

Kargas 2014). Telecommunication industry started as stated—owned monopoly but it was one of the first sectors that privatization occurred, while new forms of regulation achieved significant levels of competition among providers over the years. Market liberalization and companies’ privatization brought operational changes and new era of human resource management began even before the turn of the millennium.

Nowadays, the telecommunication industry tends to first adopt from the international trends sector, as far as it concerns human resource management tools and innovative business methodologies, such as employer branding. Companies in the field are more and more aware that identifying and hiring the most appropriate (for their own goals) employees can lead to: (a) improved employer–employee relationships; (b) expanding their brand’s attractiveness; (c) improved possibilities in achieving future profitability; and (d) “exploiting permission”. Such a condition implies that all possible workers are recognized as significant candidates and contributors to the brand. Meanwhile, in the last ten years, new challenges emerged for human resource managers working in the Greek business environment; these include the economic crisis, growing technological changes, the need for specialization and ongoing training, as well as the role that social media seems to play in all kinds of business operations.

The current study aims to evaluate the extent and depth of employers’ branding usage in the telecommunications industry. Research focused on revealing whether or not employer branding is used by Greek telecommunication companies as a means to strengthen their brand’s reputation. In order to achieve this, two telecommunication companies were selected, taking into account that both already implemented employer branding as a tool for boosting their branding reputation in a five-year program. The first company provides both fixed and mobile services, while the second is concentrated in the support of technical infrastructure and the network of operators. This kind of differentiation is helpful in order to evaluate possible alterations due to different market orientation (such as retail services over technical support services). A series of interviews with HR managers (supervisors of the employer branding program) were taken, in order to reveal the philosophy and the goals of their programs, as well as the means used to accomplish their business goals. Emphasis was given on revealing how employer branding affects the methodologies of attracting and selecting in human resources.

The rest of the paper is organized as it follows.

Section 2 and

Section 3 define employer branding and present current tensions.

Section 4 presents the methodology used, while the results of the research are presented in

Section 5. Finally,

Section 6 discusses the conclusion and further recommendations.

2. Defining Employer Branding

“Brand(ing)”, according to the American Marketing Association (AMA), is used as a sign, symbol, or design, or/and a combination of all three that is identified with the product or service of an organization and differentiates it from other goods and services. Employer branding is an extension of the above-mentioned definition, although it is mainly associated as a term with the HR administration science. It gained interest in the 1990s and soon started its development; after the millennium is has become more and more important. Ambler and Barrow introduced it as a separate theory in 1996. Their aim was to expand branding techniques beyond products and services (related with “customers”) to employees by promoting the advantages and positive characteristics of the brand’s working place as a criterion for choosing “where to work” (

Ambler and Barrow 1996). By following such a perspective, they put “employees” where traditional branding theory tends to put “consumers”, while “employers” (and conditions of employing) took the “brand’s” place. The proposed framework aims to support the idea that each brand (“employer”) can use a mix of tools and methodologies to convince the labor market (“consumers”) about its superiority/working perspectives/working conditions. Such a framework is far different from current research interests that are mainly targeted on increasing employees’ commitment to the company (

Aaker 1991) or expanding our understanding on “why” companies use resources to disseminate their brand’s name and value (

Backhaus and Tikoo 2004).

Even though employer branding has gained research and business interest, there is not a widely accepted definition. Such a situation comes from the dyadic nature of branding that has both theoretical and practical approaches that differentiate according to the national and business environment. Regarding it theoretical approach, employer branding has a lot in common with the basic principles of relationship marketing (

Kottler 1992;

Morgan and Hunt 1994). Relationship marketing studies aspects such as (a) strategies for attracting high level employees, (b) developing better relationships between senior and junior level employees, and (c) employees’ satisfaction. Employer branding expanded on relationship marketing aspects by creating a more homogenous and holistic framework, directly related to companies’ core values and working place conditions. A strong employer brand should associate the values of an organization, the HRM strategies, and the HR policies with the company’s brand, following recommendations from the

Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (

2008).

Sullivan (

2004) defined employer branding as a long-term strategy targeting three distinct groups: (a) existing employees and their effective management; (b) future or attracted wannabe employees; and (c) third parties related with the company and having interest via cooperation.

Armstrong (

2006) stated that employer branding is the cultivation of a specific organizational image, by developing a brand’s reputation related not only with its core business but moreover with its widely-accepted reputation as an employer. Finally, according to

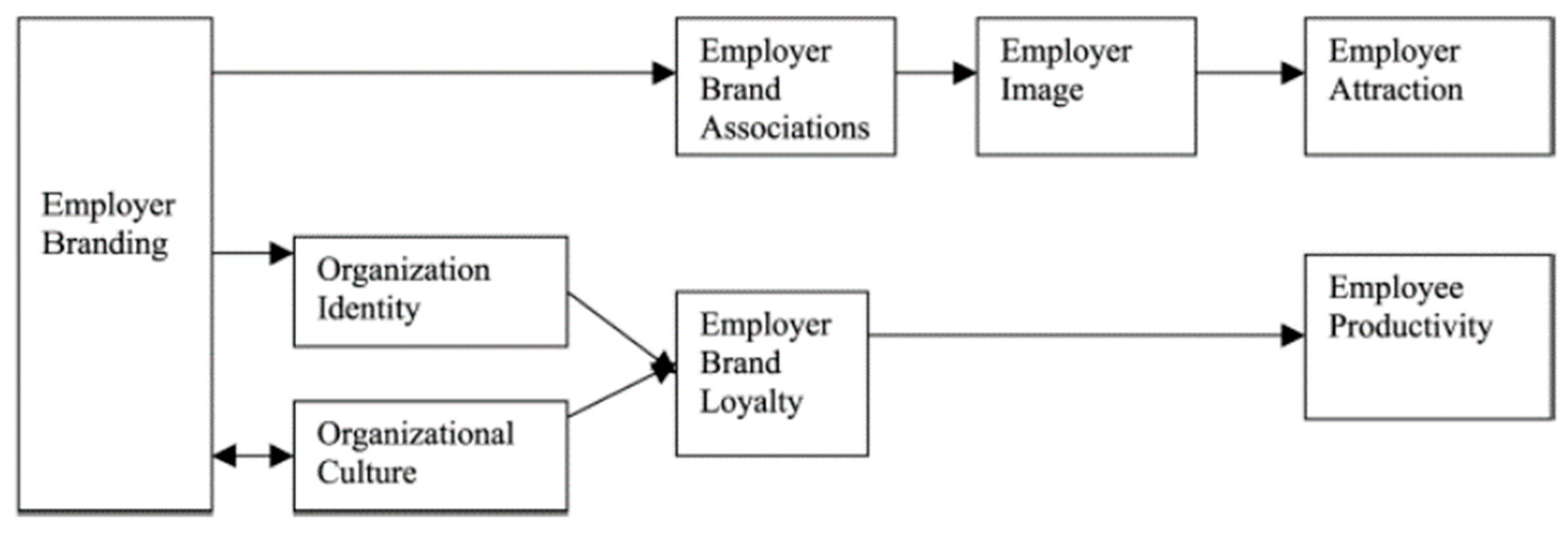

Backhaus and Tikoo (

2004), employer branding is a three-stage procedure (

Figure 1):

In the first stage a company develops its distinct values that are related with operational, everyday working characteristics, in an effort to create an exceptional working place;

In the second stage the business disseminates its values and promotes its workplace in order to attract future employees; and

Finally, it integrates these values as part of its organizational culture, in order to homogenize staff and reshape its internal business environment.

It is a circular procedure, where HR managers “imagine–promote–incorporate” what can play a significant role in an employee’s choice about its future working place. Even though this is far from defining what employer branding exactly “is”, it is close enough to what it “does” and what “should be done from HR managers”. The description of implementing employer branding reveals five major steps to be followed:

Step 1: the comprehension of the organization, by understanding what the brand’s values and its main operational characteristics are;

Step 2: the creation of a “fascinating brand promise” for the employees;

Step 3: estimation of goals’ achievement, by developing internal indexes of effectiveness;

Step 4: the alignment of the methods applied in order to support branding; and

Following these steps does not necessarily guarantee success in attracting the best employees when competition is high but can increase the possibility of maintaining high-skilled personnel already working in a brand and moreover can attract talents and senior level professionals.

3. Bringing Employer Branding to the 21st Century

Having almost completed the second decade of the 21st century, businesses have already hired staff from the so-called Millennial generation, whose members were born between 1974–1994 (

Yunita and Saputra 2019). Today’s young “go-getters” are those that will bloom and become the mature executives of tomorrow in the labor market. Ignoring the needs and preferences of those executives will just lead them to competitors capable of benefitting from human resources.

As

Vance (

2006) pointed out in an SHRM article (Society for Human Resource Management), working candidates are like customers. Nowadays candidates have choices. They choose their employer, the exact same way they look for a product they want to buy and then, they expect the process of commitment with a potential employer to be as accurate and transparent as they are looking for.

Unlike other generations the Millennials wish “their language to be spoken”. A Fortune article (

Stahl 2016) titled “Employers, Take Note: Here’s What Employees Really Want”, mentioned that this generation seeks transparency in the labor market and there is a purpose to what they do. That means they most likely respond to an open, democratic company culture which gives priority to communication between employees and executives. Moreover, another important factor seems to be the desire for smaller and more cooperative working places (less mass, industrial working places), where each employee is appreciated for his/her vital role.

All the above led to inevitable changes in traditional HR. As far as the candidates’ attraction is concerned, social media seems to play an increasingly important role. It is more and more common to use social media to run employment campaigns which aim to create the image of a positive employer brand. Accordingly, the power of social media popularity leads to increased transparency. Interaction between company and employee is no longer a secret, and a positive or negative experiences can easily become widespread. This fact points out the need for accurate and thorough caution for every advertisement or/and commentary referring to the brand of an employer.

At the same time, the use of social media as a tool for attracting employees has changed. For example, although the majority of those seeking a job seem to prefer LinkedIn, the role of videos as a branding and recruiting tool should not be underestimated or ignored. Embedded or cross-referenced, each video should respond to the following three dimensions:

entertaining;

thought-provoking; and

fascinating.

in an effort to get the attention of possible executive candidates seeking a new career.

On the other hand, taking for granted the relationship between this generation and social media, information is instantly transferred onto Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, LinkedIn, and other platforms. These channels can be used as a means of communication as well as a forum to create employer branding. It is clear that employer branding must place itself in the spotlight of this relationship for a “youth-conscious overall brand image”. HR departments can transform Millennials hired into representatives of the company’s brand, by supporting their desire to promote via social media their working place and aspects of their working daily life. Since the employees themselves tend to be companies’ representatives in the social media world, the reputation and the image of an employer depend more than ever on its standard values and organizational culture.

As mentioned by Clayton in Harvard Business Review (

Clayton 2018), an increasing number of businesses recently started to realize that the CEO himself is responsible for the executives’ working experiences, as far as employer branding is concerned. This observation aptly appoints the strategic importance of employer branding, while underlining the significance of the HRM.

Meanwhile, the

LinkedIn Talent Solutions (

2016) report shows that employer branding is a fundamental priority for employers. In fact, employer branding investment has significantly increased within the last couple of years. Moreover, organizations tend to have a more proactive strategy and use more outbound channels, like online networks and the social media. It is widely accepted that the world of attracting talented people has changed, and employers seem to cooperate more and more with marketing departments, in order to meet traditional (e.g., sales) and more alternative goals (related with employer branding). This case is also supported by LinkedIn’s report (

LinkedIn Talent Solutions 2016), according to which 47% of employers work directly with the marketing department and claim that “a strong relationship with marketing will be the key to master the employer branding”.

4. Research Methodology and the Sample

For the purposes of the current research, an empirical approach was chosen by collecting data from two companies in the communications field. The two particular companies where chosen as a result of the fact that they both decided to use employer branding as a long-term strategic tool for the enhancement of their reputation. They already had a five-year original program and the project began in 2017–2018. Moreover, from a statistical point of view both companies operate on the national level as a whole and both have a significant market share.

The first company is a well-established telecom provider (called “Telecom Operator” for the rest of the paper), widely known to the public, that provides both fixed and mobile telephony services. It has approximately 2400 employees, and in the last seven years has invested more than 1.5 billion euros in fiber optic networks, 4G mobile network, and 4G+ mobile services. Moreover, it supports Internet Protocol TV (IPTV) services and has a 24-h customer support service. Its main characteristics are:

55% of its employees are women and 45% are men.

the average age is 38 years old; the youngest employee is 20 years old and oldest is 62 years old.

the company keeps it employees’ number stable, by hiring 1 person for every 1 person who leaves the company

28% of its employees have a master’s degree.

77% have a bachelor’s degree.

97% of its employees are working with a contract of unlimited time; after the economic crisis most contracts in Greece were subjected to a limited amount of time (e.g., one year).

the company operated a HR department from the first day of its business activity.

80% of HR activities are covered inhouse, while the remaining 20% are covered from external contractors.

The second company is a new firm (called “New Firm” for the rest of the paper) that entered the telecoms market in 2014. Its core activities cover the areas of network design and engineering, network deployment, and network operations and maintenance. Its main objective is to manage the Radio Access and Transport Networks (RANs) and implement a partially active radio network sharing (MORAN) for 2G, 3G, and 4G technologies mostly in rural and in selected urban areas of Greece. Its technical background leads to a non-market facing company providing services exclusively to telecom operators. Its main characteristics are:

278 employees.

208 versus 70 women.

women have 18.8% of the company’s managerial positions.

all employees are working with a contract of unlimited time.

each year (since 2015) the redundancy percentage is 1.4%, while the company hires new employees for each loss.

each employee receives up to 22 hours of training each year.

in 2019 the company was awarded the “Best Places to Work” award (sixth position in Greece for companies with more than 250 employees).

The two companies were also selected in order to ascertain whether there are statistically significant differences as a result of giving emphasis in different markets (retail service market versus strictly network oriented services). By choosing such a compilation of companies, the results indicate that employer branding not only affects external-environment oriented companies (e.g., companies that aim to deliver high-quality products/services to customers), but also companies with a more internal-environment orientation (e.g., aiming to support other companies).

Thus, a series of interviews for each company were conducted with the executive HR managers that supervise the employer branding program. The goal of these interviews was to reveal the philosophy and goals that each company has for its employer branding strategy as well as the tools/methodologies used to accomplish that. For these reasons, the key questions were the same for the two companies (15 questions). The purpose of these questions was to create an open discussion, while their number led to a two-hour open interview for each company.

The interviews included both qualitative and quantitative questions in order to evaluate how employer branding techniques were implemented and moreover how HR managers evaluate their current contribution. In order to evaluate the reliability of the questionnaire, Cronbach’s alpha was used, revealing an overall reliability of 0.851 (

Table 1), which exceeds the 0.7 that is needed to guarantee the final results (

Cortina 1993).

In the following section the results are presented, giving emphasis on the qualitative perspective in order to understand the strengths and weaknesses coming from the implementation of employer branding in the Greek business context. Afterwards some quantitative results are presented in order to evaluate how respondents respond to employers’ branding techniques and daily working life.

5. Research Results

Interviews conducted revealed existing practices related with employer branding, as well as the outcome obtained. Methodologies used from both companies to implement their employer branding strategy are similar in a large degree, even though there are small but significant differences. Both companies have two distinct categories of operational actions related with employer branding: (1) internal-oriented actions that aim to improve employees’ working experience and (2) external-oriented actions that aim to promote the brand via a set of different communication channels.

Internal-oriented actions aim to give the employee a pleasant working experience by reducing any negative thoughts/feelings against the employer. Moreover, this kind of action leads employees to act as company ambassadors by impelling them to share everyday working moments through their own social media. In most cases, word of mouth can create a widespread reputation among audiences that no company can reach. The actions described during the interviews involved (for both companies):

Abiding training options for personal employee improvement in his/her career.

Extra insurance programs for the employees.

Pleasant and open workplaces.

Flexible work shifts and the possibility to work from home.

Alternative outdoor entertainment activities or well-being activities.

As far as external-oriented actions are concerned, it is worth mentioning that focusing on social media is the main strategic option. Social media is used as a means for companies to differentiate themselves from other employers and promote their uniqueness and add value to their brand’s identity. Most heavily used social media platforms are LinkedIn, Facebook and Instagram, while it has been revealed that different types of social media are used for different types of actions, such as:

Open discussions with the academic community (both professors and students) during educational visits to the company.

Open discussions with the academic community during employees’ visits to various universities.

Graduate programs for university graduates.

Targeted projections, conferences, and seminar visits.

Career days in universities.

Projection of their actions through social media, like LinkedIn.

Leaving aside all the above-mentioned similarities, a series of differences were revealed, concerning “how” employer branding actions were applied. The most significant difference was highlighted on how social media is used as an HR professional tool. The first company, which is a less active player in the labor market than is known by telecommunication service users (the wide public), is inactive in LinkedIn which is considered the “Facebook” for companies. It is however active on other social media forums, such as Instagram and Twitter, and keeps an active career page on Facebook where it announces actions and vacancies. On the contrary, the second company, a technological company less known to the wider public, heavily relies on LinkedIn as its main tool for promotion and communication, constantly updating its actions.

Moreover, in order to promote their brand (as employers) both companies take part in “career days” and telecommunication conferences. Telecom provider aims to disseminate its internal operation and promote its brand as an employer, while the latter company is primarily concerned with attracting telecom providers’ interest rather than gaining attention in the labor market.

The results of implementing an employer branding strategy is not yet clear according to the interviews. When interviews were conducted, two out of the five years of implementation were completed. Despite this, the interview revealed trends worth mentioning. For example, results supported the idea the companies with a strong employer brand have a competitive advantage in attracting the talents they seek. The results support findings from the

Employer Brand International (

2009) that points out that almost half (49%) of employees are interested and influenced by the reputation of a company and such a parameter plays an important role in their decision about their future workplace.

Our research indicates that according to the provider-company, right after the first year that employer branding was applied, the company became one of the top “influencers employers” on social media alongside other popular brands, such as ones from the banking sector. HR managers have also noticed a better fit regarding the resumes received, meaning more quantity and quality at the same time. In addition, internal-oriented actions, according to employees’ surveys, revealed that employer branding reinforced their positive opinion for their own workplace and enhanced their commitment towards the company up to 78%.

As far as it concerns organizational and operational benefits coming from a strong employer brand the results from the interviews indicate:

Candidates’ quality improvement: the results indicate that companies with strong employer branding find it easier to hire qualified candidates since the applicants are already aware of what the company stands for. A properly communicated brand helps those who seek a job to understand why they would not be suitable for a specific company.

More active candidates: Solid employer branding helps attract candidates that are not interested in changing jobs.

The Corporate Leadership Council (

1999)conveyed a study in 1999 that proved that effective employer branding allows companies to have access to a larger talent range. The study which was carried out from 58,000 new employments and permanents from 90 organizations showed that the organizations that have manageable employer brands can find employees from more than 60% of the job market, while those with no employer branding have access to just 40% of the job market. The current study’s results support these findings.

Less cost in employment process: Results support the idea that by having an imposing and well-advertised employer brand message, it is more likely that the candidates will ask more information on their own about a vacancy. Thus, this procedure saves time and money from seeking candidates from ground zero, because the need for advertising a vacancy and the waiting time until someone becomes interested is smaller.

Brand advocates: A result that was never clearly mentioned but was implied during interviews was that when people love their job, they tend to talk about it more. Therefore, employees can be helpful in tracking and attracting new talents. Since they know what it takes to fit in and work in a company, the employees are the most suitable to judge who is suitable to embed in a company. They also know how to “sell” (promote) a business, since they know very well what they are looking for from an employer.

Less cost in terms of the turnover: Current research could not reveal such a connection as a result of their willingness (as it was expressed via interviews) to keep stable and clear their employer branding. It has been proven that companies create a bad employer brand when they do not keep their promises given during an interview or on employment, causing a way bigger turnover.

As far as quantitative results are concerned, the questionnaire involved three large groups of questions regarding: (a) attracting candidates, (b) choosing candidates, and (c) evaluating existing employees. The questions were conducted on a five-scale climax, while the results presented are aggregated for the whole sample per company. The results regarding how employer branding is related with attracting candidates are presented in

Table 2.

Both companies attract candidates from the market, but with a different intensity. The “New Firm” mainly attracts candidates from other companies offering a better contract and at a second level it attracts candidates from the market. From the other side, the “Telecom Operator” has a more neutral strategy equally targeting the market and professionals from other companies.

Both companies mainly attract candidates when a need arises, either as a result of someone leaving the company or when extra employees are needed. Moreover, both companies use their website and LinkedIn as the primary means of attracting candidates, but the similarities end up to this point. Facebook is used only by the “Telecom Operator” to attract candidates, while the presence of the “New Firm” in social media is just typical. The difference lie in the targeted audience. The “New Firm” is interested in already developed professionals (from academic and working experience perspectives), while the “Telecom Operator” targets millennials who heavily use Facebook, putting an emphasis on recruiting and “developing” wonder kids. The same perspective exists regarding the use of Instagram as well, even though both companies have a less intense presence in this social media. Finally, it is worth mentioning that both companies use alternative channels for attracting candidates. “New Firm” has established a graduate program targeting young professionals, while “Telecom Operator” established a woman reconnecting to the company program, targeted on increasing the number of women working for the company.

Both companies incorporate the above-mentioned means and techniques to attract candidates, as part of their employer branding strategy. “New Firm” has set as a goal for implementing employer branding, to be recognized from telecom professionals as one of the best national employers and in 2019, the company was awarded as one of the “Best Places to Work” in Greece. “Telecom Operator” set a goal to be one of the top-five companies recognized as best workplaces but did not achieve this goal for 2019.

Finally, both companies recognize that their employees’ opinion about them has improved as a result of employer branding implementation. “New Firm” reports that more than 78% of its employees have a more positive opinion, while “Telecom Operator” reports that its employees’ perspective classifies the company among the top influencers as far as social media use is concerned.

In the field of choosing candidates, the two companies have many similarities (

Table 3). First of all, both companies use curriculum vitae and interviews as their basic means to evaluate candidates. “New Firm” has a more structured questionnaire used during the interviews, while “Telecom Operator” has a more flexible approach following the specific needs of each job position. This was expected due to the more specifically oriented working field of the “New Firm” (technical services). “Telecom Operator” has a larger variety of working fields.

Both companies use role-playing tests but only for higher, managerial positions; this technique is not applied for regular employees. It is worth mentioning that this kind of approach was a result of employer branding implementation. As far as “who” makes the final decision for hiring, both companies have specialized managers from their HR departments. The choosing criteria involves (for both companies) aspects regarding: (a) candidate operational and professional capacity, related with the job description and (b) aspects of behavior and cooperation with colleagues.

Finally, the last aspect was the evaluation of existing employees (

Table 4). Both companies have a procedure of evaluating existing employees, while processes have been changed in the last two years as a result of employer branding implementation. The whole procedure takes part at the “department degree”, while the evaluation is conducted by each department’s manager and HR department holds an advisory and supervising role. The goals of evaluation are similar: (a) operational goals reached (for each employee) and (b) behavioral goals and cooperative attitude. Both companies have ranked as sufficient for the whole procedure and goals settled.

Both companies avoid ranking employees but follow a more conversational approach, targeted on highlighting strengths and weaknesses, in order to empower and motivate employees to improve themselves. Even though this is the goal, it is not easily achieved, and it seems that more steps have to be done. Evaluation under the Greek national context is often related with dismissals, especially when companies are following a cost reduction procedure. A slight difference occurs to feedback given and setting new goals. “Telecom Operator” has a procedure that when evaluation is ended, the department’s manager and each employee set the goals for the new year, taking into account results achieved from the previous year. On the contrary, “New Firm” established a procedure that each department’s manager sets the goals for the new year according to the department’s needs and employees are just informed about them. At the same time, both companies take actions regarding the results of evaluation and employees are supported by additional training, transferring to different department, bonuses, etc. In all cases, respondents seem satisfied with the actions taken.

6. Conclusions and Further Recommendations

The current research presented and analyzed employer branding as a theoretical framework and as an operational methodology. Prior research has mainly investigated employer branding antecedents and outcomes at the individual-level of analysis (for review, see

Theurer et al. 2018), while the current research placed emphasis on a business sector (as a whole) that is characterized by intense labor competition and constant efforts to develop and maintain skillful personnel. Such a sector is the Greek telecommunication industry, which is constantly evolving and related to innovation at a technological level and company strategy level as well. New sources for gaining competitive advantage are implemented, mainly related with non-technological factors, such as organizational culture (

Kargas 2014), market orientation (

Papadimitriou and Kargas 2012), and of course, human resource management.

Employer branding has arisen in the last years as a new source of efficiency and telecommunication companies in the Greek business environment have adopted its methodologies and started five-year programs of implementation. The results derived from the current research indicate a positive relation between employer branding and the prospect of reinforcing the company’s reputation. The interviews conducted revealed that employer branding can give better results on methodologies used to attract skillful talents capable of adjusting quickly and more accurately to the company’s culture. These talented new employees are expected to become companies’ future assets, capable of delivering competitive advantage. Moreover, employer branding also contributes to raising of employees’ confidence and motivates them to give their best.

Greek telecom operators seem to have quickly reformed their HR techniques to employer branding initiatives, as far as choosing candidates is concerned. Many similarities exist between the companies that were used as a research sample. From an empirical point of view, the more market-oriented a company, the more intense their use of HR techniques. Attracting new employees by using employer branding techniques has evolved in the last three years, while the use of social media has expanded as a means to attract candidates. Most significantly, it is worth mentioning that traditional means, such as corporate websites and forums/career days, have been overweighed by Facebook, LinkedIn, and more focused programs targeting millennials, graduate students, and women professionals. As far as evaluation of existing employees is concerned, more work is needed on exploring new means of evaluation and providing feedback to employees, both in association with the brand’s image. Further development of means and techniques in these fields could improve current employees and job seekers’ perception about the firm and its possible consequences.

Consequently, even though significant changes have occurred, HR staff feel that employer branding targets have not been fully achieved. At the same time, it should not be neglected that employees’ perception about the results coming from the employer branding implementation are of high value. These findings support this idea even though the extent of use of employer branding techniques is not high (because of the short time from its initial implementation).

The results presented in the previous section are consistent with the conceptualization of

Aggerholm et al. (2011) involving (a) branding, (b) human resource management, and (c) corporate social responsibility (

Figure 2), in order to develop a framework in which employees are treated more and more like stakeholders rather than a labor force. By doing so employees are becoming part of a bidimensional dialogue with the employer instead of the means to achieve high added value for the companies’ owners (e.g., stakeholders).

These conclusions, however, come from interviews that were made with HR departments, while the programs’ initial life cycle has not yet been completed (five-year programs in total with only two years of implementation). That means that the results mainly reveal a tendency and further research is needed in the future. Such an approach does not reduce the validity of the results, taking into consideration that the sample companies’ top-management support expanding employer branding program, while more and more resources (e.g., financial and human resources) are given to support its success. During the research, there were restrictions regarding the information given about the companies’ actions. Following internal security procedures, information about complete depiction actions was impossible to be given.

As part of future work, we propose the reevaluation of the programs after the end of the five-year timetable, in order to compare results and allow for more quantified data to be collected. Moreover, the current research could not reveal such a connection as a result of the short time that employer branding programs have been operational. Following recent trends on business environments, it is rather important to expand our understanding of the interaction between employees and employers’ branding as part of companies’ change through Industry 4.0 implementation. The main goal of Industry 4.0 is to achieve the integration between physical, machinery and devices (Cyber Physical System—CPS) with networked sensors and software (IoT), creating complex but accurate systems capable of predicting, planning, and controlling societal and business outcomes (

Industrial Internet Consortium 2013).

In such an environment, skillful and experienced “human resources” will be of the same importance as any other rare resource used to develop products or to support services. All evidence show that the Fourth Industrial Revolution will bring the human factor into the first line of research, but in a manner where physical and virtual environments will interact, and data will be transferred. Treating employees equal to customers (following employer branding trends) is a mean to develop a responsive organizational culture, capable to adapt to the forthcoming business environment.