Abstract

We examine decision-making, shared authority, and pluralism as key characteristics for the effective co-management of natural resources. Drawing on the concept of network governance, we complement this approach by studying localized practices of governance that support existing and compensate for missing aspects in the regulation. The regime of territorial use rights for fisheries (TURF) in Chile is a recognized example of large-scale co-management that has given rise to local organizations that manage and exploit benthic resources. Based on multi-sited qualitative fieldwork across five regions, we analyze practices with respect to two governance objects: the deterrence of illegal fishing and the periodic assessment of the fisheries’ biology fields. Our analysis shows that local fisher organizations have institutionalized informal practices of surveillance and monitoring to fill in the gaps of existing regulations. Although fisher organizations and consultants—the so-called management and exploitation areas for benthic resources (AMERB)—have managed to operate the TURF regime, they depend on the government to enforce regulations and receive public subsidies to cover the costs of delegated governance tasks. We suggest that governance effectiveness could benefit from delegating additional authority to the local level. This would enhance the supervision of productive areas and better adaptation of national co-management regulations to the specific geographical context.

1. Introduction

Recent debate on the governance of natural resources suggests that both hierarchical government as well as free market mechanisms may be limited in providing for consensual and sustainable resource use. Instead, public–private partnerships, strategic pacts, dialogue groups, consultative committees, inter-organizational networks, etc. have been discussed as alternative forms of achieving an inclusive, collective and binding governance of resource exploitation [1,2]. The fact that scholars have demonstrated the failure of top-down governance arrangements in practice requires new approaches to address collective coordination among different stakeholders [3]. In this context, co-management has become a popular concept that aims at “sharing power and responsibility between government and local resource users” [4]. Therefore, it has been suggested that this type of management follows an inclusive form of governance through which stakeholders can achieve their social and environmental objectives [3,5,6].

Berkes [7,8] argues that co-management as a rights regime not only involves government systems and local-level systems, but is also a “cross-scale interaction” perspective. This is a relational position on understanding socio-ecological systems that addresses the multi-level and multi-stakeholder nature of governance as well as its organizational and spatial connectivity. This involves designing and maintaining bridges that especially empower and connect the local level with other higher levels of social and political organization. In the policy arena, there has been a growing trend in recent decades to use the co-management approach to natural resources, especially from the point of view of developing state policies, plans, and programs. Consequently, there are a significant number of cases in which co-management measures have been conceived including forests [9,10,11,12,13], water [14,15,16,17], and fisheries [18,19,20,21,22,23], among others.

These changes in public policy can be seen as part of the governments’ responses to the rising uncertainty in socio-economic, political, and environmental scenarios as well as the widespread processes of distributing management responsibilities due to the privatization and deregulation that have occurred in the spheres of the state [24,25]. Despite this, co-management is not necessarily a panacea capable of always solving the dilemmas of collective coordination [26]. In practice, although a variety of strategies and measures have been applied from this mode of management, this has not guaranteed positive outcomes in each and every case [3,27]. One of the main reasons may even exceed the actors and scales and is rather related to the core of the co-management vision and the role of the state (i.e., the plausible ways the latter can give back power and responsibility to the agents in this type of rights regime). The experience suggests that this point is crucial, but also complex, among other things, because of the hierarchical nature of the modes of governance provided by government management and upon which it has traditionally based its power. Due to this, despite the existence of a legal framework to enforce a co-management model, such distribution ends up being more nominal than effective [28,29].

This problem continues to challenge research in this area. We aimed to understand the ways in which the actors formally and informally enact patterns of stable interactions to effectively exercise power and fulfil their responsibilities in co-management practices. We recognize that this requires a complementary perspective that builds on the logic of co-management, but puts more emphasis on agency and connectivity at the local level of governance. We argue that the local level of governance, while being embedded in a national regulatory regime, compensates for gaps and potential failures in formal regulation and may (or may not) provide local adaptation that finally enhances governance effectiveness in the specific geographical context. Accordingly, we ask what legitimate governance arrangements local stakeholders establish within a national co-management regime, and how they affect the performance of such rights regimes.

The rest of this article is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the debate on fisheries co-management and adopts a network governance framework to complement the co-management approach. Section 3 illustrates the case of the regime of territorial use rights for fishing (TURF) in Chile and presents the two central objects of governance for this research. Section 4 explains the methodological design to address the case study from a qualitative approach. Section 5 presents the results of the analysis of the two network scenarios for deterring illegal fishing (poaching) and cooperation in the periodic assessments of the fisheries biology. In addition, the results are discussed while taking into consideration already existing research about the management and exploitation areas for benthic resources case (AMERB—Áreas de Manejo y Explotación de Recursos Bentónicos). Section 6 concludes the analysis with implications and future questions for a research agenda.

2. Governance from Hierarchies to Networks

2.1. Co-Management

Scholars in the field of the co-management of natural resources have found specific characteristics for effective governance among diverse stakeholders, which include decision-making, shared authority, and pluralism [25,26]. In this article, we focused particularly on those linked to co-management systems in fisheries. Decision-making is related to a deliberative process through which the parties resolve collective problems and pursue common objectives. This requires a negotiation structure capable of especially involving the local users of the resources [26,30]. In theory, this feature of co-management is considered an important means for interested parties to influence forms of cooperation [28]. Nevertheless, although there has been an increase in management efforts to include fishers in the planning and management of their resources, they perceive that they ultimately have limited influence over crucial decision-making in rights regimes [31,32]. Therefore, the inclusion of multiple stakeholders in formal decision-making does not depend exclusively on a formal structural issue of the state, but also on non-state actors appreciating that their experiences, concerns, and objectives are included in co-management agreements and policies [33].

Closely linked to this is the shared authority of the parties involved, which has been understood as the empirical distribution of state power [26]. At the level of fisheries management, one of the challenges of co-management is that delegated authority should not simply be an act of proclamation of good intentions or the desire of the agents involved in government entities, but rather a restructuring of the formal channels through which governments can effectively confer competence and authority in the management of resources [34]. Indeed, Pieraccini and Cardwell [35] argue that shared authority addresses the heterogeneity and independence of the positions of relevant actors who are aware of multi-stakeholder participation. If this is effectively practiced, all those involved should formally be part of collective negotiations in the interest of legitimate consensus and mutually acceptable decisions. Moreover, an additional aspect in this sense refers to the delegation of decisions to local management contexts, which especially enhance the monitoring capacity of the fishers, making them guarantors of both the protection of their productive fishing areas defined by the formal rights regimes and the monitoring of the conditions of their fisheries and the ecosystem as a whole [36,37].

It is equally important to recognize that fisheries management agreements must be legally accepted by the state, but at the same time, the latter must recognize that each geographic location has specific actor constellations, institutional, regulatory, and environmental conditions, and thus locally poses particular challenges to effective governance [29]. Pluralism refers to embracing the diversity of the perspectives and backgrounds of actors in addressing a particular problem in multi-stakeholder coordination [26]. One of the crucial questions is whether co-management leads to the legitimation of state regulations by local users, and whether these regulations are sufficiently effective to adapt to the diverse contexts of local rules of appropriation and provision of resources [38,39]. Yates [40] argued that fishers tend to understand the need for stricter controls on fishing to sustain their long-term productive viability. However, this will be considered acceptable by local users as long as they perceive that these fisheries planning measures have been discussed collectively and that their regulatory and cultural contexts are integrated in the co-management agreements and procedures.

The legitimate and effective delegation of power and responsibility to local-level systems is linked not only to the ability of users to exclude third parties from the exploitation of scarce resources, but also to their capacity to monitor their productive zones [41,42]. The latter includes the appropriators in the processes of evaluating the fisheries’ biological conditions and, therefore, this information, which was previously in the hands of scientific entities, guarantees them the knowledge and with it, to formally participate in spaces of negotiation for agreements with fisheries administration (e.g., in the establishment of sustainable extraction quotas) [33]. Likewise, this same component would formally delegate additional authority and capacity to fishers, allowing them to be the first to respond to stop illegal fishing and reduce fishing efforts if necessary [37,43]. In the next point, we specifically address an alternative to understand the role of agents in said monitoring capacity, and how their agencies at the local level complement the gaps and failures of the co-management systems.

2.2. Network Governance

The co-management of natural resources is a form of governance that, by its nature of a rights regime, entails formal and informal agents and mechanisms of coordination at multiple scales, particularly between the government and local systems. This interaction not only represents a specific form of coordination, but also reveals the agency of the actors and the social networks in which they are embedded [44,45]. Network governance, in this sense, offers an approach to understanding the emergence of these social orders of horizontal and voluntary coordination [46]. We refer to network governance as organized structures and procedures in coordination, and decision-making is based on negotiation and consensual agreement among stakeholders. The adhesion of the participants is therefore a critical factor because it is voluntary and grounded on acceptance by the participants [2,47,48].

In theory, network governance implies not only the establishment of horizontal coordination, but also that agents can collaborate in an enabling context of the constant exchange of resources and trust [2,49,50], despite the fact that in practice, agents often have different access to resources and authority [47]. Co-management systems often imply a significant amount of heterogeneity among their actors, which has a direct impact on power asymmetries and, eventually, on the unsuccessful legitimization of formal regulations within the network [51,52,53]. Thus, pluralism becomes important as another element of co-management that recognizes the need for both the structure of the rights regime and the local agency to be periodically adapted to the contexts and enjoy flexibility in finding arrangements [54,55].

Rhodes as well as Mayntz and Scharpf [56,57] argued that networks could be influenced by a hierarchical framework such as the state. Nevertheless, network governance is expected to encourage interactions through consensus, avoiding the intervention of a unique authority [46,58]. Whereas government entities establish the formal regulations of co-management, network governance plays a complementary role in providing reliable structures of social relations among the involved actors for the development of legitimate collective coordination outcomes [46,59]. Therefore, network governance should occur in the space where these diverse actors participate in designing and sustaining common objectives such as multilevel and sustainable monitoring of natural resources.

Glückler [47,60] distinguishes four elements of network governance: context, object, agency, and mechanisms. First, the “context of governance” refers to the specific geographical location, configuration of actors, and socio-political conditions in which coordination and collaboration are to be organized. In co-management scenarios, networks can be complex to the extent that actors vary in interests, resources, power, and scopes of activity [44]. It is therefore crucial to analyze the “trans-boundary interactions” as a process in which actors practice governance in both formal and informal contexts [61]. The second element refers to the “object of governance” (i.e., the specific common goal to which coordination is dedicated). Depending on the particular object, the local organizational structure and procedure may vary accordingly, and adapt to the specific objects of governance [2]. Another essential factor of voluntary participation in a governance network is the perceived transaction cost incurred on individual actors that affect their position of being in or out of the collective action framework [22,62]. Third, “agency of governance” is related to situations in which control processes are developed in the organizational units with legitimate power to exercise governing in the networks [60]. In the field of network governance, typologies of forms of agency based on formal authority have been established [63,64] as well as decentralized forms of self-governance [48,65]. The agency may be constituted formally (e.g., organizational units or panels) or informally as coordinated actions by resource users at the local level [47]. Finally, the agency deploys “mechanisms of governance” that can be formal such as contracts, directives, and other regulations as well as informal (e.g., social institutions of trust, reciprocity, and reputation of network members) [47]. Consequently, the agency of governance builds relatively stable patterns of procedures and interactions that are generally considered legitimate among members and thus facilitate effective and consensual coordination outcomes [59].

In what follows, we aim to combine the concept of co-management of natural resources with a complementary perspective of network governance and to apply it to the regime of territorial use rights in Chile. Our main objective is to analyze the local coordination efforts among multiple stakeholders and to examine whether and how institutionalized practices ultimately fill in the existing gaps of formal regulations in Chilean co-management of benthic resources.

3. Territorial Use Rights for Fisheries (TURF) in Chile

3.1. The Control Contexts Before of the Territorial Use Rights for Fisheries (TURF) Regime

The process of Chile’s economic liberalization in the mid-1970s had an impact on its natural resources and its trade dynamics. Industrial and small-scale fisheries were no exception. Activities that had previously satisfied the domestic demand now increased the capture of species for export [24]. This was the case with the fishing of the loco (Concholepas concholepas), a gastropod mollusk, which under a free access regime reached an average landing of 16,000 tons per year between 1975 and 1984, almost three times the value of the earlier period (1965–1974) with nearly 5000 tons per year.

A few years after the loco fishing boom, the resource became overexploited. Although the governmental administration for fisheries imposed seasonal bans in 1982 and 1985, international demand, particularly from Asian markets, continued to imply resource exploitation [66,67]. Given the attractiveness of the loco, many people linked to benthic fishing migrated to new territories in search for new loco banks such as the Los Lagos region in southern Chile, and specifically to the Greater Island of Chiloé. This migration triggered conflicts between the local inhabitants and newcomers, a situation known as the “fever of the loco” (la fiebre del loco) [66,68].

In 1988, the socio-ecological unsustainability of fishing led to one of the first control mechanisms for the exploitation of resources. The system of total allowable catches (TAC), however, did not have the expected effect because it was unfeasible in practice due to the short legal period for extraction and illegal catches. Finally, loco fishing was restricted by a general ban between 1989 and 1992. However, given the strong international demand, extractive activity prevailed through illegal landings and other activities outside the regulatory margin such as loco smuggling and the laundering of this resource in neighboring countries [69,70,71,72].

The over-exploitation and clandestine fishing required a more restrictive management system that granted registered users the right to access the resource through individual quotas, called the benthic extraction regime (RBE). In practice, the loco quotas were set up through global captures defined for each regional division. This measure was applied at the national level between 1993 and 1999. The RBE also suffered deficiencies because it was almost impossible to control all landings, enforce legal requirements through the atomization of quotas, and provide real incentives for the sustainable management of fisheries resources [72,73].

3.2. The Enforcement of the TURF Framework for Benthic Fisheries

Continued overexploitation of loco and a lack of regulations in the fishing sector led to the challenge of broader legislation. In 1991, the so-called General Law of Fishing and Aquaculture (LGPA) was promulgated and included the introduction of the management and exploitation areas for benthic resources (AMERB) as a model for the territorial use right for fishing (TURF). Another specific measure served to regulate small-scale activities such as the inclusion of the small-scale fishing registry (RPA—Registro Pesquero Artesanal) and the obligation of the local user to belong to a small-scale fishers’ organization (OPA—Organización de Pescadores Artesanales). From that moment on, the resource appropriators only had to work in one political and administrative region of the country and with specific categories of productive and fishing activities. This new legislation was intended to influence the traditional migration of fishers [71,72] and to promote a micro-entrepreneurial perspective in the local fishing activity [68].

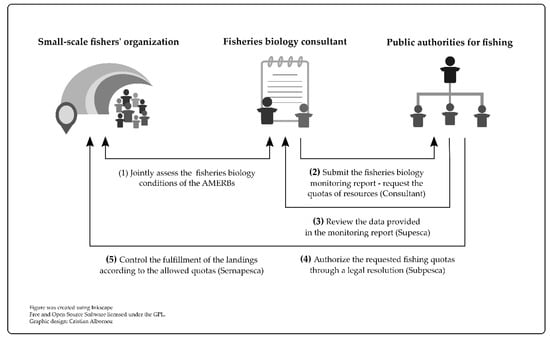

The AMERB legal regulations came into force in 1995. Two years later, the first AMERBs or “management areas”—as they are known by local users—were set up. This co-management system involved three clearly defined groups of actors, often referred to as the “AMERB triumvirate” [74]. Thus, the coordination basis was the OPAs, which would become the unit of local production and management of resources, while the public fisheries authorities were divided into the administration (Subpesca—Subsecretaría de Pesca y Acuicultura) and the control (Sernapesca—Servicio Nacional de Pesca y Acuicultura). Finally, it gives a role to external consultants as advisors in the fisheries biology field, particularly in the execution of periodic monitoring reports (informes de seguimiento), and forms the main link between the local level and public entities (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Simplified scheme of formal processes in the management and exploitation areas for benthic resources (AMERB) co-management system.

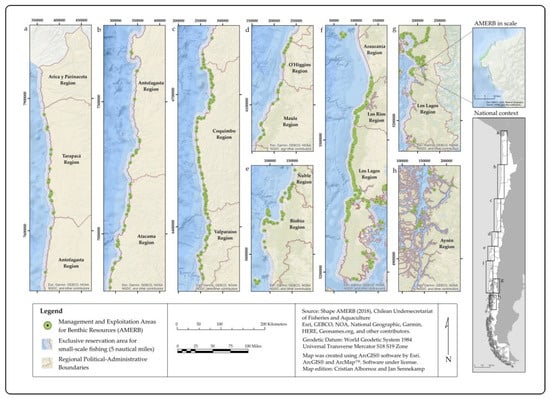

According to official data, a total of 504 AMERBs were in activity by 2020. All TURFs were located within the “Small-Scale Fishing Reserve Area”, that is, in the first five nautical miles from the northern border of the national territory to the south of the Greater Island of Chiloé (Figure 2). The AMERBs occupy an approximate surface of 70,000 hectares, with a number greater than 16,000 users formally organized. Furthermore, there are more than 70 target species (mollusks, echinoderms, crustaceans, and algae) where the following benthic resources are highlighted: loco (Concholepas concholepas), species of limpets (Fissurella spp.), urchin (Loxechinus albus), and species of huiro-algae (Lessonia spp. and Macrocystis pyrifera) (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

AMERBs in activity according to the regional division of Chile.

Figure 3.

(a) Locos from an AMERB authorized harvest. (b) Small-scale fishing unit with hookah diving system. (c) Locos in natural habitat, corresponding to AMERB sampling unit. (d) AMERB members harvesting and drying Luga algae on the beachside. Source: Authors. Authorized pictures with confidentiality agreement.

The fishers’ organizations were transformed into essential units for the implementation of measures such as the formal application of a TURF to the authorities, which can only be done by organizations duly registered in the Registry of Small-Scale Fishers’ Organizations (ROA—Registro de Organizaciones Artesanales). Currently, these organizations can be unions, labor associations, indigenous associations, cooperatives, or other independent organizations. In this regard, it should be noted that there are currently 352 organizations that have rights over the 504 AMERBs operating at the national level. Of the total of these OPAs, two-thirds of this number regularized their organizational status after the enactment of the 1991 LGPA. This reveals, in part, the absence of general guidelines for the formal organization of fishers, and/or the flexibility of fishers to participate in different economic sectors or extractive work groups.

Ultimately, the AMERB produces monitoring reports that are useful to the extent that they result in an official request to the authorities for setting a local fishing quota. To conduct these fisheries’ biological assessments, the AMERB system obligates OPAs to assign external consultants to jointly issue the monitoring reports. According to our statistical analysis, 94 consultants participated in the TURF regime between 1997 and 2017. These advisory units present a clear heterogeneity of organizational structures and objectives. These were divided into private consulting firms (61), academic sections and/or research centers of universities (29), foundations (3), and a public fisheries research entity. In addition, they are not usually large advisory offices; in fact, one or two specialists usually work directly for the AMERBs. Therefore, they usually provide services to AMERB organizations in the same political-administrative regions where they are located, apart from a few exceptions.

3.3. Two Objects of Governance in the AMERB Context

There is ample scientific research that refers to the AMERB system, which is considered as an international example of large-scale co-management [5,75,76,77]. These works have highlighted several aspects of the TURF regime including the governance at multiple geographical and organizational scales. In the Chilean co-management system, public authorities require fishers to (1) organize themselves into a legal entity (AMERB), and (2) assign external consultants to evaluate the conditions of the fisheries, which are then reported to the public administration. The latter evaluates the accuracy of the assessments and then specifies the quota allowed locally in a season. In our empirical analysis, we aimed to analyze two objects of governance and ask (1) how local user groups deter the illegal fishing of benthic resources, and (2) how they interact with mandatory external consultants to produce regular fisheries biology monitoring of the AMERB.

Regarding the first, it can be highlighted in general terms that the AMERB system does not formally guarantee surveillance of the areas, which means that poaching persists. Scholars have suggested that the AMERB system operates in parallel with a “de facto open access regime” [67]. Indeed, illegal fishing has been rather widespread, although it must be recognized that it has varying degrees of exploitation and impact depending on the region at the country level. It has been documented that poaching has diverse sources of origin such as the members of the AMERBs themselves, the organizations of neighboring fishers [78], users expelled or excluded from the organizations, and/or those who have never registered with the RPA [79,80]. The extreme scenario of poaching is that developed by groups that have obtained economic, logistical, and technical extraction capacities that in many cases exceed those of the affected coves. This last case is the one we will address, in which the networks present a stable coordination for surveillance against what local users call the “mafias del loco”, and which has meant, among other things, significant economic losses for the OPAs as well as confrontations and even costs in terms of human lives.

The second object refers to the challenge that the AMERB system has in terms of its administrative application and the evaluation of the areas on an extensive scale across almost the entire country. As we have pointed out, this implies that the OPAs are linked to an advisory unit, which is a unique way for the management of resources on a small scale in the country. Scholars have argued that, on one hand, this has promoted greater access of the fisheries’ organizational sphere to technical cooperation projects [75,81] as well as more effective inclusion of resource user groups in certain government management arrangements [75,82]. However, at the same time, it has been suggested that this has led to the production of multiple assessment methodologies for AMERB, the lack of a standardized format, thus compromising the quality of data reported to public authorities [67,72,74] as well as the absence of concrete channels of dialogue between scientific and traditional knowledge in order to contribute to the decision-making processes [72,74,83]. In this article, we focused on the relational stability of actors beyond bureaucratic directives and examined the role of the consultant as a linking organization between the fisher organizations and the formal entities of the TURF regime as well as the interactive process of developing the assessment reports.

4. Methodology

We adopted a qualitative case study approach [84,85] as well as elements of the relational method of “situational organizational network analysis” (SONA) [86]. We collected data during two stages of fieldwork in 2018 and 2019, covering five political-administrative regions of Chile. Overall, we carried out 38 semi-structured interviews with diverse groups of stakeholders including 14 interviews with OPA-leaders, 8 with officials related to public administration and control of benthic resources, and 16 with consultants.

The informants were selected using specific criteria, which were directly related to the two objects of governance (Supplementary Material, Table S1). Regarding poaching deterrence, we interviewed the leaders of the OPAs that had implemented long-term surveillance systems as well as organizations that had managed this type of system, but were not able to maintain it over time. They were all located in the Los Lagos region. Consultants were regarded as those who provided training or development of AMERB surveillance projects. Regarding the representatives of public authorities, we interviewed those directly responsible at the local level in the area of greatest conflict with poaching practices. With respect to drafting the monitoring reports, we interviewed the leaders of the OPAs who had established stable relationships with their consultants (i.e., those that reported no or only one change in the last 15 years, and those that had made between three and six changes in the same period). The consultants were selected on the basis of their experience in AMERB consulting. In addition, members of the public sector were consulted both in the regional units and at the national central level of the Valparaiso region.

We conducted all interviews subject to written agreement of confidentiality and anonymity of the parties. The average recording time of the interviews was about one and a half hours excluding the recording period of the rapport process with the informants. In line with the SONA methodology, we focused on the interaction patterns that identified and contextualized the elements of network governance. Additionally, we considered the motivations and expectations as well as the practices, incentives, perspectives, and experiences around the two objects of governance. We transcribed interviews entirely, submitted transcripts to the content analysis software MAXQDA by VERBI Software, and coded the text according to a tree of conceptual categories we developed for the analysis (Table 1). To enhance the validity of our interviews, we used secondary information to triangulate the data produced in the field and to support the ideas presented in this article. Specifically, we generated our own database according to the AMERB’s monitoring reports, TURF requests, and the fisheries’ biology baseline studies. In total, we added 1230 cases (number of cases registered as formal TURF applications) and we focused on the analysis of the 504 areas of effective operation. The specific data used for this study were the typologies of small-scale fishers’ organizations and consultants, term of relationship between OPA and consultants, fishery performance according to allowed quotas, and the landing quotas of resources.

Table 1.

Framework of the concepts and categories of analysis.

5. Results

5.1. Networks to Deter Poaching in AMERBs

Although deterrence from illegal fishing is a major challenge affecting the ecological and productive performance of the AMERB, it is not considered as an element in the co-management of the Chilean TURF. This is evident by the fact that in the monitoring reports, there is no section in which the OPAs, through their consultants, can periodically estimate the impacts of illegal fishing on their management areas. Consequently, the AMERBs cannot request additional measures to deal with this type of indirect violation of the fishing quota [87]. Hence, local actors have generated their own and more informal governance practices to respond to non-compliance and to help protect their territories in several ways (Table 2a,b). We refer to evidence collected in our interviews in the Los Lagos region (southern Chile), where illegal exploitation of loco takes place in areas surrounding the coves.

Table 2.

Selected quotes from the interviews.

Beyond the co-management system, the Chilean state, through its Technical Cooperation Service (Sercotec—Servicio de Cooperación Técnica) has responded to poaching issues by financing organizations (e.g., in the training for AMERB users) and the acquisition of conditioned boats, surveillance cabins, and radar stations. Indeed, the Los Lagos region reports the highest number of public funds granted for this matter, which in total amounted to a little more than one million dollars between 2013 and 2018 (according to Sercotec sources, 2019). Nevertheless, leaders of OPAs with rights over the AMERBs believed that these efforts were not sufficient to deter illegal fishing, despite the eventual support of the Chilean Navy or Sernapesca, as the OPAs found the effective control of poaching to be a very complex task (Table 2e). Certainly, in the interviews, local actors openly indicated their concern about the lack of authority and shared competencies with governmental entities because they require specific measures not only to dissuade poachers, but also to control them. AMERB users are not authorized to enact any effective sanctions because seizing benthic resources or arresting poachers remains the sole responsibility of governmental authorities. Such lack of power to act has generated skepticism by the fishers’ organizations (Table 2f) because effective and continuous formal controls are not available or even possible. However, this limitation of authority in practice did not restrict actions being taken by local organizations. OPAs did take action to prosecute poachers and accepted the costs of such surveillance (Table 2g).

Government subsidies proved insufficient, and those networks lacking incentives were unable to pay for permanent surveillance systems (Table 2c). However, continuous surveillance is necessary to guarantee compliance with the object of governance. The AMERB networks pointed out that paying for monitoring systems throughout the year meant a reduction of between 10 to 15% of their annual benefits (Table 2d). In addition, our fieldwork revealed that there were more than one fishers’ organization in the same fishing town, where one of them successfully carried out surveillance whereas the others could not or simply did not maintain surveillance efforts, nor did they work collaboratively with other OPAs. We argue that this is due to the way in which the context of formal control, which generated the atomization of fishing communities into formal organizations, influences collective action in interorganizational networks. Leaders of OPAs believe that collective coordination to support surveillance systems at the intra-organizational level depends on the annual yields of their AMERB fisheries from which they obtain the funds to maintain surveillance of their management areas. This is expressed through the cost-benefit appraisal of providing monitoring of an AMERB (Table 2g). It was often pointed out that if the harvest of their resources was not as expected, they would not have funds to cover the costs of supervision either, which would explain why in many cases the organization’s surveillance networks tended to operate intermittently.

In the absence of the effective delegation of authority to local agencies and of a legitimate pluralism of local oversight rules conferred by official government mechanisms, voluntary governance networks fail to adapt to local challenges and thus also fail to comply with the quotas transferred by the state. Although regulations of co-management have given rise to a space for local action that did not exist prior to the 1990s, local governance still lacks the authority to discourage illegal fishing. The Chilean state has given legal users the responsibility of creating a wide range of “local rules of position and limits” [43]. OPAs have the power to define internal rules, allowing them to manage the number of appropriators who may belong to the organization or to sanction members who violate the agreed-upon codes by means of legal statutes of the organization’s constitution. Although this would reduce the impact of poaching by members of the organizations themselves, most respondents reported that they had to deal with cases in which they had to sanction their colleagues who were caught fishing illegally either in their own or neighboring management areas. Although the creation of local collective entities has allowed for a certain pluralism of organizational statutes that has made local control possible, in many cases, surveillance efforts remained incomplete or ineffective. This is because, in practice, the legitimacy of local regulations may vary from one organization to another as well as the validity of their application over time [79].

Recently, an idea has been promoted to enforce criminal prosecution of the poachers [82]. However, the public prosecutor’s office argues that it lacks legal and procedural resources to prosecute groups or individuals for poaching. Currently, there is a system of support for prosecutors (SAF), which in relation to the General Law on Fishing and Aquaculture, does not contemplate a specific side for the illegal extraction of AMERB resources despite the elaboration of SAF code 12022 to include all other infractions of this law (Public Prosecutor’s Office. Written communication, February 2019). While it is important to address poaching at the legal level, resource users and consultants did not believe that this would improve the situation. Essentially, they criticized that additional regulation would still not replace better enforcement.

Instead, the state has invested in technical solutions such as the delivery of unmanned air vehicles, building of radar stations, or the installation of signs with legal information of the AMERB on the beaches. However, this did not resolve the problem (Table 2h). The OPAs argued that it was unlikely that individuals or groups could be prosecuted before the authorities based solely on audiovisual evidence, therefore, they did not usually make complaints because in the end, they were incredulous of the effectiveness of the system. This suggests a lack of certainty on the part of the networks, who did not base their expectations on the cooperation that public entities could provide them through formal government mechanisms. Instead, the local organizations explained that they would prefer to obtain resources directly to better prepare for surveillance themselves as well as to cover the expenses related to its ongoing maintenance.

In this respect, it is clear that AMERB co-management is a form of hierarchical governance that guides the rights regime and has alienated resource users from the formal system. Given the non-involvement of non-state stakeholders, certain fishers’ organizations have adapted and achieved an approach to monitor and control their areas in a rather informal way, but without a system of authority mechanisms backed by the legal framework. Therefore, the Chilean model of co-management in this aspect evidences a top-down model, with a predominance of formal structures and the state as the controlling partner, tending to dominate most of the possible interactions that local agents could make around the effective control of illegal fishing. This explains why there are only certain cases of effective networks to have stopped poaching in the management areas, because, in practice, there is a clear lack of delegated authority to the fishers and insufficient recognition of their experience in formalizing official bodies that support their work as monitors of their AMERBs.

5.2. Consulting Networks in the AMERB Co-Management Scenario

The partnership between fishing organizations and consulting firms in the Chilean TURF regime is mandatory, as shown by the AMERB regulations, a particular situation for small-scale resource exploitation systems at the national and even continental level. This governance mechanism is due to the fact that the organizations have an external advisory unit to replicate relatively standardized procedures such as baseline studies and monitoring reports. In contrast, pluralism and shared authority within this co-management system are often interpreted in interviews with members of public entities as the independence of small-scale fishers’ organizations to choose a consulting unit and manage funding for such technical assistance themselves. This makes it an object of governance, expressed as a formal requirement (Table 3i).

Table 3.

Selected quotes from the interviews

According to our statistical analysis of the 504 AMERBs, 315 of them were established before 2002 and 151 were created in the following five years. Consequently, 92% of the management areas had been operating for at least 10 years in the TURF regime at the time of study. This allowed us to understand the relational behavior among the actors during a significant period and at the national level. If OPAs have the power to hire a consulting firm, it is possible to calculate the number of variations in the consulting market, the national average being 2.3 times the number of firm changes made by an AMERB. It is also crucial to point out that the two regions with the largest number of AMERB organizations, Los Lagos and Coquimbo, have historically had the highest annual average of consulting offers with 14 and 13 units, respectively (between 2002 and 2017). However, the higher number of firms has not led to greater dynamics of change as both remain close to the national average.

We expected a certain relational stability in the resulting networks, at least with regard to the achievement of the formal objectives of the TURF regime, where the obligatory nature of the monitoring report explains in the first instance the existence of such a link. This is an important point, if we compare it with the few examples of networks in the first case, because the object of their governance is based on the voluntary character of each OPA. In both situations, the AMERB networks depend strongly on government subsidies. Furthermore, inter-organizational networks between fishers’ organizations and consultants have emerged from another objective of governance in this type of network (Table 3j). Consulting firms support technical work by having their own evaluation criteria and their empirical experiences and they comply with the requirements of the biological evaluation of fisheries imposed by the public authority. Thus, before the request for the quota of resources to be exploited during the season, which is included in the monitoring report, there is usually an effective negotiation process between the local users and their technical counterpart. These negotiations are based on the expectations of the users, mainly about obtaining the best possible yield from their fisheries. In this case, the consultants must manage the reasonable and sustainable rate allowed for the quota request. The interaction can be between the consultant and leaders of the OPAs or more broadly, in which the entire assembly of members of an organization participates. Indeed, this negotiation process between fishers and consultants is an agency of governance for the control of performance and management policies of fisheries at the local level. Consequently, it means that these two stakeholders have, in practice, more decision-making capacity over their management areas than public entities have through formal control mechanisms (Table 3k,l).

There was no evidence of stable entities that proved sufficient for the delegation of formal authority to this type of network (i.e., to organizations and consultants). Indeed, the independence of OPAs to hire a consulting firm was only a question of compliance with formal requirements. The most interesting aspect is what happened under this requirement, and it was rather the possibility that networks could establish “aggregation rules” [43], that is, structures to comply with the non-state stakeholders’ expectations and objectives. The latter was part of an informal authority and explains in part how the relationships of the inter-organizational networks were sustained. A quarter of all AMERBs (504) had never changed their consultants during the period after their establishment. Therefore, these networks serve as examples of stable coordination, which makes use of the compliance with the bureaucratic requirements of the regime. Additional informal entities supported this network stability and occurred in parallel to the AMERB system. This is what Schumann [88] refers to in the AMERB system as “quality of interaction through contextual issues”, where there is a series of interactions based on the consultant’s technical contribution to the productive and organizational development of OPAs. Based on our interviews, two lines of argument emerged, which we considered to be components of the central object of governance. On one hand, there was the perception of the relevance of the consultancy as an organizing element of the organizations’ activities, and on the other hand, the assessment of the associated transaction costs that coordinating agents associate in order to execute the biological assessments as well as the process of obtaining the legal quotas allowed.

The first component refers to the idea that organizations require integral support beyond the execution of the monitoring reports. Representatives of the OPAs mentioned that generating reports was not their only argument for maintaining the link with their consultants because they also evaluated how the consultant could provide them with support in the generation, formulation, and/or execution of projects to promote fishery production. This declaration was made by both organizations that maintained stable relationships with consultants as well as by those who had changed consultants in the past. In both cases, they appreciated the consultants who they had worked with (on site) in the fishing coves. According to the consultants, the networks they had developed with the organizations were based on the extent to which they could establish close collaborative ties, which they called the “fishers’ loyalty way”. In fact, they had to demonstrate that they were capable of providing advice beyond the evaluations, and thus of ensuring their contractual relationship and even legitimacy in the face of OPAs. This is a crucial agency for governance at this level because it explains the role of the consulting sphere that informally leads to the AMERB system (Table 3m).

In interviews, fishers’ organizations often perceived the consulting firms as the channel for communicating with and receiving information from the government [88]. Furthermore, they argued that this link was vital because it was a way of “organizing” OPAs, not only in the sense of managing the AMERB, but even with other tasks that they entrusted to their consultants. This collaboration was even demonstrated in the repeated verbal expressions of the leaders in some coves in which they characterized their consultants with the appellation of “our advisor” or “our professional” (Table 3n). Despite this, it was not possible to verify in the fieldwork with the organizations that all the members of the organizations agreed with the presence of this external party. The effect of this linkage is also related to the connection that consulting firms can provide to OPAs with public and/or private entities that promote the development of small-scale fishing (Table 3o). The leaders of the organizations maintained that without an entity to act as a link, in this case, the consultant, their access to the co-management system would be restricted or complex due to the asymmetries of information and power that they perceived when referring to public entities.

The second component refers to the possible low cost of elaboration offered by certain consultants to execute the evaluations of the reports that could affect the quality of data reported to the authorities [67,89]. The transaction (monitoring) cost plays an important role in the object of governance. At the time of study, a monitoring report had a value ranging from US$ 1300 to US$ 5200. Organizations typically internally coordinated to cover the value of the report, either by members themselves or by requesting support from public or private entities through project funding. However, in our observations, we found that the cost of a report would not be the main factor of the low quality of the results. Consultants reported that the evaluation costs also depended on the provider of the funds (OPA or third party), whether the fishers accompanied the consultants to the sampling tasks (in diving), or even on the years of linkage that the consultant had established with the organizations.

Public authorities considered the cost of monitoring reports to be a secondary issue. Instead, they held that the problem of the data quality reported was due to the lack of standardization of the sampling methodology, which subjects all consultants to comply. According to them, standardization would allow them to perform analysis for the adoption of public policies in the area of fisheries, beyond the mechanism of authorization of the requested quotas. This has led Subpesca to request the Research Institute for Fisheries Development (IFOP—Instituto de Fomento Pesquero) to formulate a standardization manual for data sampling in the management areas (Table 3p). Public entities have included consultants in this process. Despite this, in the interviews with the consultants, arguments against this approach prevailed because they felt that they were not considered in an effective space for dialogue and decision-making where they could establish their points of view and collaborate in the standardization according to their experiences in empirical sampling (Table 3q).

Finally, it is important to note that by examining the internal procedures of the fisheries authority, it was possible to find a formal governance mechanism, which is also relevant for the formal stability of the networks. This has to do with the evaluation that the Undersecretariat makes of the reported data. Evidently, the success does not lie in the control that they make, but in the fact that this public entity has the bureaucratic power to grant or reject the “legal resolution” for the extractions of the quotas requested by the OPAs. However, in the event that a report is rejected by an administrative entity, it previously urged the consulting firms to clarify or modify the inconsistent information. In the interviews that we conducted with Subpesca, they claimed that they would normally contact the consultants to request amendments. They themselves acknowledged that the rejection of a report had only occurred on rare occasions. What is important about this process is that it has allowed authorities to distinguish between the quality of data reported by one consultant and another, which in turn implies a mechanism based on institutions such as the prestige and trust given to certain consultants (Table 3r). If the authorities constantly questioned the reports of their consultants, the local AMERBs would run the risk of obtaining their legal resolution late and not being able to harvest during the legal season (Table 3s). This last argument is often associated with organizations that commonly exploit and depend on the yields of their fisheries.

6. Conclusions

The Chilean TURF regime is an initiative promoted by the state that has rendered co-management a claim for a hierarchical control structure rather than a delegation of power and responsibility to local stakeholders. We have demonstrated that it is difficult to include the pluralism of local rules into the formal framework. Moreover, we have portrayed informal governance mechanisms that local stakeholders have developed during or even before the establishment of the legal framework for TURFs. Decision-making among stakeholders has been restricted to a formal compliance framework such as the generation of periodic AMERB monitoring reports, but does not include the stable relationships between actors and social institutions that end up underpinning the rights regime. Likewise, the AMERB system has failed to delegate authority to the support required locally to ensure the stability of surveillance networks. Illegal fishing has been viewed as an externality and is not included in the governance mechanisms that would encourage stakeholders to protect and monitor the management areas. In practice, neither small-scale fishers’ organizations nor fisheries consulting units are part of the collective decision-making processes and structures with government entities. Therefore, if this top-down co-management structure is maintained, necessary adjustments to the TURF regime are unlikely to occur.

The two objects of governance examined in this article are closely linked to a critical component of any sustainable management system, namely the effective monitoring capacity of local users. In a rights regime such as AMERB co-management, this should be reflected in the authority and responsibilities delegated to fishers so that they are both the overseers of fisheries biology and active agents monitoring and evaluating the conditions of their fisheries resources. This requires a formal structure of the delegation of powers and competences as well as a framework of regular subsidies. Such re-organization of the governance structure might stimulate the social incentives necessary to enforce crucial governance objects effectively at the local level. This necessarily implies a collective learning process that integrates the experience of fishers, consultants, and authorities into regular decision-making structures, and that gives them a relevant role so that they themselves can collaborate in future adaptations required by this co-management model.

Our analysis reflects the need to further investigate how localized governance among actors at the local level may support and compensate for the shortcomings of rights regimes such as the TURF in Chile. More knowledge is needed about how local networks of actors actually organize governance practices in order to elaborate on a transformative perspective of natural resource management. We have contributed by including both formal and informal aspects of the governance processes and structures.

Finally, we would like to propose a research agenda to further explore relational practices within resource governance by using methods of social network analysis as well as identifying the specific attributes of these networks, which ultimately support the development of sustainable natural resource management. In both cases, we argue that there is a need for an interpretive analysis that specifies the content of networks and the role of social institutions in the development of linkages among and between members of the OPAs, consultants, public authorities, and other stakeholders. We also consider it appropriate to specify how it would be possible to do a structural analysis of the way in which the various parties legitimize the formal arrangements for the development of the AMERB system within the network.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3298/7/12/104/s1, Table S1: List of interviews conducted in the research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.A. and J.G.; Methodology, C.A. and J.G.; Fieldwork, C.A.; Software, C.A.; Formal analysis, C.A. and J.G.; Writing—original draft preparation, CA.; Writing—review and editing, C.A. and J.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), grant number 91609001 and the Kurt-Hiehle Foundation

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the people belonging to the small-scale fisher’s organizations, public entities, and consultants who collaborated in this research. At the same time, we extend our gratitude to the anonymous reviewers as well as to the reviews and comments provided by Maximilian Benner, Michael Handke, Xuan Hu, Regina Lenz, Robert Panitz, Claudia Sandoval López, Juan José Sanz Donaire, and José Julian Soto Lara.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ostrom, E. Beyond markets and states: Polycentric governance of complex economic systems. Transnatl. Corp. Rev. 2010, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen, E.; Torfing, J. Introduction governance network research: Towards a second generation. In Theories of Democratic Network Governance; Sørensen, E., Torfing, J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2007; pp. 1–21. ISBN 978-0-230-22036-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ayers, A.L.; Kittinger, J.N. Emergence of co-management governance for Hawai‘i coral reef fisheries. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 28, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F.; George, P.; Preston, R.J. Co-management: The evolution in theory and practice of the joint administration of living resources. Alternatives 1991, 18, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Marín, A.; Berkes, F. Network approach for understanding small-scale fisheries governance: The case of the Chilean coastal co-management system. Mar. Policy 2010, 34, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cundill, G.; Fabricius, C. Monitoring the governance dimension of natural resource co-management. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F. Cross-scale institutional linkages: Perspectives from the bottom up. Drama Commons 2002, 15, 293–321. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes, F. Commons in a multi-level world. Int. J. Commons 2008, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D. Principles and Practice of Forest Co-Management: Evidence from West-Central Africa; European Union Tropical Forestry; Overseas Development Institute (ODI): London, UK, 1999; p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Klooster, D. Institutional choice, community, and struggle: A case study of forest co-management in Mexico. World Dev. 2000, 28, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollenberg, E.; Edmunds, D.; Buck, L. Using scenarios to make decisions about the future: Anticipatory learning for the adaptive co-management of community forests. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2000, 47, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matose, F. Co-management options for reserved forests in Zimbabwe and beyond: Policy implications of forest management strategies. For. Policy Econ. 2006, 8, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumbe, C.B.; Angelsen, A. Forest dependence and participation in CPR management: Empirical evidence from forest co-management in Malawi. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 62, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, E.J. Indian tribal sovereignty and water resources: Watersheds, ecosystems and tribal Co-management. J. Land Resour. Environ. Law 2000, 20, 185–222. [Google Scholar]

- Falkenmark, M.; Folke, C.; Wallace, J.S.; Acreman, M.C.; Sullivan, C.A. The sharing of water between society and ecosystems: From conflict to catchment–based co–management. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2003, 358, 2011–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susilowati, I.; Budiati, L. An introduction of co-management approach into Babon River management in Semarang, Central Java, Indonesia. Water Sci. Technol. 2003, 48, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghorbani, M.; Ebrahimi, F.; Salajegheh, A.; Mohseni_saravi, M. Social network analysis of local stakeholders in action plan for water resources Co-management (case study: Jajrood River in Latian watershed, Darbandsar village). Iran. J. Watershed Manag. Sci. Eng. 2014, 8, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Pomeroy, R.S. Community-based and co-management institutions for sustainable coastal fisheries management in Southeast Asia. Ocean Coast. Manag. 1995, 27, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilla, J.C.; Fernandez, M. Small-scale benthic fisheries in chile: On co-management and sustainable use of benthic invertebrates. Ecol. Appl. 1998, 8, S124–S132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauck, M.; Sowman, M. Coastal and fisheries co-management in South Africa: An overview and analysis. Mar. Policy 2001, 25, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yandle, T. The challenge of building successful stakeholder organizations: New Zealand’s experience in developing a fisheries co-management regime. Mar. Policy 2003, 27, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makino, M.; Matsuda, H. Co-management in Japanese coastal fisheries: Institutional features and transaction costs. Mar. Policy 2005, 29, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkerton, E.W. Local fisheries co-management: A review of international experiences and their implications for salmon management in British Columbia. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schurman, R.A. Snails, southern hake and sustainability: Neoliberalism and natural resource exports in Chile. World Dev. 1996, 24, 1695–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, R.; Fitzgibbon, J. Co-management of natural resources: A proposed framework. Environ. Manag. 2004, 33, 876–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plummer, R.; Baird, J. Adaptive co-management for climate change adaptation: Considerations for the Barents region. Sustainability 2013, 5, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J.R.; Degnbol, P.; Viswanathan, K.K.; Ahmed, M.; Hara, M.; Abdullah, N.M.R. Fisheries co-management—An institutional innovation? Lessons from South East Asia and Southern Africa. Mar. Policy 2004, 28, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jentoft, S. Fisheries co-management as empowerment. Mar. Policy 2005, 29, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jentoft, S.; Bavinck, M.; Johnson, D.S.; Thomson, K.T. Fisheries co-management and legal pluralism: How an analytical problem becomes an institutional one. Hum. Organ. 2009, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, L.G.; Berkes, F. Co-management: Concepts and methodological implications. J. Environ. Manag. 2005, 75, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pita, C.; Pierce, G.J.; Theodossiou, I. Stakeholders’ participation in the fisheries management decision-making process: Fishers’ perceptions of participation. Mar. Policy 2010, 34, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semitiel-García, M.; Noguera-Méndez, P. Fishers’ participation in small-scale fisheries. A structural analysis of the Cabo de Palos-Islas Hormigas MPA, Spain. Mar. Policy 2019, 101, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, K.L.; Schoeman, D.S. Incorporating the spatial access priorities of fishers into strategic conservation planning and marine protected area design: Reducing cost and increasing transparency. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2015, 72, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, A.P.; Nielsen, E. Indigenous people and co-management: Implications for conflict management. Environ. Sci. Policy 2001, 4, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieraccini, M.; Cardwell, E. Towards deliberative and pragmatic co-management: A comparison between inshore fisheries authorities in England and Scotland. Environ. Polit. 2016, 25, 729–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castello, L.; Viana, J.P.; Watkins, G.; Pinedo-Vasquez, M.; Luzadis, V.A. Lessons from integrating fishers of arapaima in small-scale fisheries management at the Mamirauá Reserve, Amazon. Environ. Manag. 2009, 43, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancaster, D.; Haggarty, D.; Ban, N. Pacific Canada’s rockfish conservation areas: Using Ostrom’s design principles to assess management effectiveness. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boelens, R.; Vos, J. Legal pluralism, hydraulic property creation and sustainability: The materialized nature of water rights in user-managed systems. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2014, 11, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jentoft, S.; Bavinck, M. Interactive governance for sustainable fisheries: Dealing with legal pluralism. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2014, 11, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, K.L. View from the wheelhouse: Perceptions on marine management from the fishing community and suggestions for improvement. Mar. Policy 2014, 48, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990; ISBN 0-521-40599-8. [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis, M.D. Networks of adjacent action situations in polycentric governance. Policy Stud. J. 2011, 39, 51–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Understanding Institutional Diversity; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-1-4008-3173-9. [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson, L.G.; Sandström, A.C. Network governance of the commons. Int. J. Commons 2008, 2, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bixler, R.P.; Wald, D.M.; Ogden, L.A.; Leong, K.M.; Johnston, E.W.; Romolini, M. Network governance for large-scale natural resource conservation and the challenge of capture. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 14, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glückler, J.; Herrigel, G.; Handke, M. On the reflexive relations between knowledge, governance, and space. In Knowledge and Governance; Glückler, J., Herrigel, G., Handke, M., Eds.; Knowledge and Space; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–21. ISBN 978-3-030-47149-1. [Google Scholar]

- Glückler, J. Lateral network governance. In Knowledge and Governance; Glückler, J., Herrigel, G., Handke, M., Eds.; Knowledge and Space; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 243–265. ISBN 978-3-030-47149-1. [Google Scholar]

- Lazega, E. Rule enforcement among peers: A lateral control regime. Organ. Stud. 2000, 21, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayntz, R. Modernization and the logic of interorganizational networks. Knowl. Policy 1993, 6, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börzel, T.A.; Panke, D. Network governance: Effective and legitimate? In Theories of Democratic Network Governance; Sørensen, E., Torfing, J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2007; pp. 153–166. ISBN 978-0-230-22036-2. [Google Scholar]

- Jentoft, S. Legitimacy and disappointment in fisheries management. Mar. Policy 2000, 24, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J.R. An analytical framework for studying: Compliance and legitimacy in fisheries management. Mar. Policy 2003, 27, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauck, M. Small-scale fisheries compliance: Integrating social justice, legitimacy and deterrence. In Small-Scale Fisheries Management: Frameworks and Approaches for the Developing World; Pomeroy, R.S., Andrew, N.L., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2011; pp. 196–215. ISBN 978-1-84593-607-5. [Google Scholar]

- Jentoft, S.; Bavinck, M. Reconciling human rights and customary law: Legal pluralism in the governance of small-scale fisheries. J. Leg. Plur. Unoff. Law 2019, 51, 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavinck, M. Legal pluralism, governance, and the dynamics of seafood supply chains—Explorations from South Asia. Marit. Stud. 2018, 17, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.A.W. The new governance: Governing without government. Polit. Stud. 1996, 44, 652–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayntz, R.; Scharpf, F.W. Gesellschaftliche Selbstregelung und politische Steuerung; Campus Verlag: Frankfurt/Main, Germany, 1995; ISBN 978-3-593-35426-2. [Google Scholar]

- Jessop, R.D. The Future of the Capitalist State; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 2002; ISBN 978-0-7456-2273-6. [Google Scholar]

- Priddat, B.P. Zur Governancealisierung der Politik: Delegation, Führung, Governance, Netzwerke. In Governance in einer sich wandelnden Welt; Schuppert, G.F., Zürn, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 352–379. [Google Scholar]

- Glückler, J. Gobernanza lateral de redes: Legitimidad y delegación relacional de la autoridad decisoria. Rev. Geogr. Norte Gd. 2019, 74, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kooiman, J. Governing as Governance; Sage: London, UK, 2003; ISBN 0-7619-4035-9. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, M.T. Network governance in fisheries. Mar. Policy 2008, 32, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provan, K.G.; Fish, A.; Sydow, J. Interorganizational networks at the network level: A review of the empirical literature on whole networks. J. Manag. 2007, 33, 479–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provan, K.G.; Kenis, P. Modes of network governance: Structure, management, and effectiveness. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 229–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazega, E.; Krackhardt, D. Spreading and shifting costs of lateral control among peers: A structural analysis at the individual level. Qual. Quant. 2000, 34, 153–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, E. Qué paso con el loco: Crónica de un colapso anunciado. Rev. Chile Pesq. 1986, 36, 143–145. [Google Scholar]

- San Martín, G.; Parma, A.M.; Orensanz, J.M. The Chilean experience with territorial use rights in fisheries. In Handbook of Marine Fisheries Conservation and Management; Grafton, R.Q., Hilborn, R., Squires, D., Williams, M., Tait, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; Volume 24, pp. 324–337. ISBN 978-0-19-537028-7. [Google Scholar]

- Meltzoff, S.K.; Lichtensztajn, Y.G.; Stotz, W. Competing visions for marine tenure and Co-management: Genesis of a marine management area system in Chile. Coast. Manag. 2002, 30, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, E. Pesca clandestina y contrabando industrial de locos. Chile Pesq. 1990, 56, 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- González, E. Territorial use rights in chilean fisheries. Mar. Resour. Econ. 1996, 11, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stotz, W. Las áreas de manejo en la ley de pesca y acuicultura: Primeras experiencias y evaluación de la utilidad de esta herramienta para el recurso loco. Estud. Ocean. 1997, 16, 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- González, J.; Stotz, W.; Garrido, J.; Orensanz, J.M.; Parma, A.M.; Tapia, C.; Zuleta, A. The Chilean TURF system: How is it performing in the case of the loco fishery? Bull. Mar. Sci. 2006, 78, 499–527. [Google Scholar]

- Cancino, J.P.; Uchida, H.; Wilen, J.E. TURFs and ITQs: Collective vs. individual decision making. Mar. Resour. Econ. 2007, 22, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, S. A tenuous triumvirate: The role of independent biologists in Chile’s co-management regime for shellfish. Mar. Policy 2010, 34, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilla, J.C.; Gelcich, S.; Defeo, O. Successes, lessons, and projections from experience in marine benthic invertebrate artisanal fisheries in Chile. In Fisheries Management: Progress Towards Sustainability; McClanahan, T.R., Castilla, J.C., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2007; pp. 23–42. ISBN 978-0-470-99607-2. [Google Scholar]

- Gelcich, S.; Hughes, T.P.; Olsson, P.; Folke, C.; Defeo, O.; Fernández, M.; Foale, S.; Gunderson, L.H.; Rodríguez-Sickert, C.; Scheffer, M.; et al. Navigating transformations in governance of Chilean marine coastal resources. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 16794–16799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marín, A.; Gelcich, S. Gobernanza y capital social en el comanejo de recursos bentónicos en Chile: Aportes del análisis de redes al estudio de la pesca artesanal de pequeña escala. Cult. Hombre Soc. 2012, 22, 131–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.J.; Kragt, M.; Gelcich, S.; Schilizzi, S.; Pannell, D. Accounting for enforcement costs in the spatial allocation of marine zones. Conserv. Biol. 2015, 29, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palma, M.; Chávez, C. Normas y cumplimiento en áreas de manejo de recursos bentónicos. Estud. Públicos 2006, 103, 237–276. [Google Scholar]

- Santis, O.; Chávez, C. Extracción de recursos naturales en contextos de abundancia y escasez: Un análisis experimental sobre infracciones a cuotas en áreas de manejo y explotación de recursos bentónicos en el centro-sur de Chile. Estud. Econ. 2014, 41, 89–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFOP. Informe Final Actividad 5: Pesquerías Bajo Régimen de Áreas de Manejo 2010–2011; Instituto de Fomento Pesquero: Valparaíso, Chile, 2011; p. 651. [Google Scholar]

- Gelcich, S.; Cinner, J.; Donlan, C.J.; Tapia-Lewin, S.; Godoy, N.; Castilla, J.C. Fishers’ perceptions on the Chilean coastal TURF system after two decades: Problems, benefits, and emerging needs. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2017, 93, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, S. Navigating the knowledge interface: Fishers and biologists under co-management in Chile. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2011, 24, 1174–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, D.M. Research and Evaluation in Education and Psychology: Integrating Diversity with Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Methods; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4522-4027-5. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-5063-3618-3. [Google Scholar]

- Glückler, J.; Panitz, R.; Hammer, I. SONA: A relational methodology to identify structure in networks. Z. Für Wirtsch. 2020, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandin, R.M.; Quiñones, R.A. Impacto de la captura ilegal en pesquerías artesanales bentónicas bajo el régimen de co-manejo: El caso de Isla Mocha, Chile. Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res. 2014, 42, 547–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, S. ¿Colaboración o colisión? La relación entre los pescadores artesanales y sus consultoras técnicas, y su relevancia para las Áreas de Manejo en Chile; Federación Regional de Pescadores Artesanales de la Región del Biobío: Valparaíso, Chile, 2008; p. 146. [Google Scholar]

- Schumann, S. Co-management and “consciousness”: Fishers’ assimilation of management principles in Chile. Mar. Policy 2007, 31, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).