Abstract

This viewpoint article examines Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) practices in developed and transitioning nations, identifies weaknesses, and proposes a new quantitative approach. The literature indicates that there exists little to no standardization in EIA practice, transitioning nations rely on weak scientific impact analyses, and the establishment of baseline conditions is generally missing. The more fundamental issue is that the “receptor”-based approach leads to a qualitative and subjective EIA, as it does not adequately integrate the full measure of the complexity of ecosystems, ongoing project risks, and cumulative impacts. We propose the application of a new framework that aims to ensure full life cycle assessment of impacts applicable to any EIA process, within any jurisdictional context. System-Based EIA (SBEIA) is based on modeling to predict changes and rests on data analysis with a statistically rigorous approach to assess impacts. This global approach uses technologies and methodologies that are typically applied to characterize ecosystem structure and functioning, including remote sensing, modeling, and in situ monitoring. The aim of this approach is to provide a method that can produce quantifiable reproducible values of impact and risk and move EIA towards its substantive goal of sustainable development. The adoption of this approach would provide a better evaluation of economic costs and benefits for all stakeholders.

1. Introduction

It has been nearly half a century since Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) became part of US federal legislation as an integral part of their environmental management program. The passage of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) legislation in 1969 fixed as objectives to “prevent or eliminate damage to the environment” and “enrich our understanding of the ecological systems and natural resources” (NEPA 42 US Code § 4321). One of the ways US NEPA legislation accomplishes this is by requiring EIAs to be performed by all federal agencies involved in projects, which could have significant human environmental health impacts, risk to ecological health, and changes to nature’s services []. EIA is thus one of the public policy instruments dedicated to sustainability. EIA is a decision-making tool intended to contribute to the economic development of societies, while limiting the impact on the environment. However, the production and use of EIA in its various forms is not self-evident and deserves improvement as new methods in natural and engineering sciences become available. In addition, an investigation through the prism of the social sciences of politics is necessary in order to understand how the EIA process and methodology can be improved on a practical level.

Environmental quality issues and natural resource management were never considered merely “local” or “national” problems. By the end of the 19th century, early nature protection movements recognized that environmental protection is both a global issue and a universal concern, albeit in the context of colonial administrations []. It was, however, not until the 1960s and 1970s that broad legal frameworks were negotiated and ratified by international community. An important step in this process was the 1972 United Nations Conference on the Environment in Stockholm, when the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) was established. During the next 20 years, many other countries followed the US and UN initiatives, including: Australia (1974), Thailand (1975), France (1976), Philippines (1978), Israel (1981) and Pakistan (1983), who all passed environmental legislation requiring environmental impact assessment []. As of 2012, more than 100 countries have instituted EIA systems [].

Even if there is a consensus about the purpose of an EIA, there is no international legislation that defines the content. EIA aims to determine what potential changes in the environment occur from economic development, utilizing, when possible, statistically robust tests inferring changes in certain receptors from consecutive (i.e., before and after) or simultaneous (i.e., paired) samplings carried out in impacted and non-impacted conditions []. Nevertheless, professional organizations, such as the International Association for Impact Assessment (IAIA), define an EIA as being strictly an a priori process:

“ […] the process of identifying, predicting, evaluating and mitigating the biophysical, social and other relevant effects of proposed development proposals prior to major decisions being taken and commitments made.”[]

EIAs are thus-based primarily on evaluating specific criteria that predict whether an impact is “significant” or not []. Currently, the significance of an impact is based on the “best professional judgement” of the EIA team: a process that relies on individual expertise and is applicable only in the context of particular projects, even if other approaches exist [,,]. Because of this commonly admitted practice, quantitative measures of impact rarely support an EIA, and very few impact analyses rely on an ecosystem-based assessment [,,,,]. The notion of “significant impact” has relied mainly on qualitative impact methodologies that were proposed as a stop-gap measure in the early 1970s, such as Leopold’s methods [], when US regulators were overwhelmed with EIA reports []. These stop-gap measures have likely contributed to hindering the development, testing and adoption of quantitative techniques, while also having the effect of reassuring elected officials who felt quantitation eroded their decision-making power []. Thus, the effectiveness of EIA can be questioned, not only regarding decision-making [], but whether it has a substantive benefit to environmental sustainability. This is an objective that has been stated as the real goal of NEPA and other major environmental legislative actions around the world [,,]. The principal objective of EIA is to ensure decisions made regarding policies and legislation are transparent and informed by the best possible evidence that can help avoid or reduce negative effects for government, industry and for society as a whole, while making it more likely that their aims are met.

In an examination of the European Union’s Impact Assessment process for member states, Jacob (2010) [] notes that the ex-ante Impact Assessment (IA) of policies is a powerful tool for integrating concerns of sustainable development as well as other cross-cutting strategies into sectoral policy-making in theory. However, there are only a few countries that explicitly refer to issues of sustainability in their guidelines for IA, notably the United Kingdom, Ireland, Switzerland and Belgium []. This can lead to shortfalls in EIA in the EU. Although all EU countries pursue the common goal to ensure coherence of new legislation with issues of sustainable development, the systems and practices of Sustainability Impact Assessment differ considerably. There is ongoing work in the EU to incorporate a tiered approach to EIA with the implementation of the strategic environmental assessment (SEA). Using both an EIA and SEA allows for the delineation of different tiers of decision making, something the NEPA guidelines do not outline as clearly. The EIA and SEA method can systematically assess environmental impact at all tiers and ultimately supporting more transparent, rigorous and systematic decision framework [,,,].

In this viewpoint article, our goal is to examine the ways in which quantification of impacts and risks to ecosystems would not only benefit decision makers for the determination of whether an impact is “significant”, but also how it would allow all stakeholders (e.g., planners, managers, economists, engineers, contractors, industrialists) to make use of data-driven modeling of the effects of project activities to predict impact on different aspects of the ecosystem in terms of a probability with a quantifiable error, as suggested by Coston-Guarini et al. (2017) []. Achieving this within the EIA framework would be moving a step closer to meeting the original intent of environmental legislation: operating with natural systems in a more sustainable manner.

2. Approach to Problem

We review the background of the EIA process and how this legislation has been implemented in specific countries. Weaknesses in EIA application in developing nations and marine environments are then discussed. We then examine the role of scientific expertise and research in the process and the increasing importance of risk assessment. We close this viewpoint by suggesting a new possibility for renewing the EIA process by integrating data from new technologies with ecosystem-based modeling and moving away from the current reliance on receptor-oriented, qualitative assessments, to an analysis of receptors in a system in which they are quantitatively linked. This viewpoint contends that movement toward a quantitative ecosystem-based EIA (SBEIA) is a viable alternative to subjective impact assessments that can be implemented worldwide, even in transitioning nations, as quantified impacts provide a means to estimate possible costs associated with project impacts and risks. We contend this type of SBEIA approach is pertinent to lenders, project proponents, and other stakeholders.

3. Background of the EIA Process

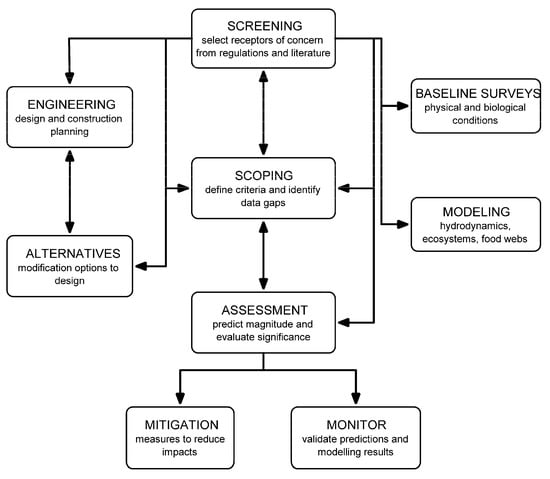

Glasson asserts that the EIA procedures adopted by the US, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), The World Bank, the European Union (EU), and other organizations and countries move through three preparatory phases prior to the start of the actual EIA [] (Figure 1). These are:

Figure 1.

Classic Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Workflow Chart. Based upon a summary of Glasson [], Wathern [], and Petts [].

- Consideration of Alternatives. This step evaluates various alternatives and approaches for the proposed action, such as different locations, scales, and designs. Many times, however, this step is neglected in both developed and transitioning nations.

- Screening. This step answers the question: does the project require an EIA? Environmental legislation or governmental authority usually governs this. Projects that might require EIA are those which might produce a significant change in a renewable resource, such as water resource projects, oil extraction, infrastructure and industrial projects, coastline development projects, mineral extraction, energy plants, and waste management. Most countries require screening of all public and private projects that require government approval.

- Scoping. Scoping is a phase that determines of the most important receptors for analysis, i.e., the ones susceptible to undergo the largest impacts. This step is intended to occur preferably before, or at least during, project development and it is also intended to develop a scientifically expert-based identification of receptors of impacts (biotic, abiotic, social, and economic). This step is usually given equal attention in both developing countries and transitioning countries [].

The actual EIA study (Assessment, sensu stricto) begins with the selection of receptors and the description of baseline conditions (Figure 1). This is also associated with the determination of the likelihood and magnitude of impacts and their significance relative to the baseline description, and the proposition of mitigation measures, if deemed necessary. Each step has several additional considerations:

- Description of baseline conditions. The baseline identification process often starts in the scoping phase by identifying gaps in available data and existing local knowledge. Baseline surveys are then completed with the aim of filling data gaps and, ideally, providing information at scales relevant to the impact assessment. Nonetheless, the definition of “baseline” appears to vary in EIA development, with some practitioners defining baseline as strictly the condition/trends in the existing environment they determine are likely to be significantly impacted. This usually consists of an analysis of receptors and the environmental processes that influence them, which include biotic or abiotic receptors and processes. However, the use of a “receptor-based” approach usually leads to baseline studies that only investigate those features that might be significantly impacted by the project, which fails to fully capture ecosystem processes and dynamics [,].

- Selection of receptors. The development of objective criteria for the selection of receptors has been an issue in EIA for decades. In general, the rationale for the selection of receptors rests on a comprehensive analysis of the landscape, the project activities, the receptors that subject matter experts consider most likely to be negatively impacted, public opinion, the realistic ability to gather baseline and monitoring data, and coordination with other sustainability efforts in the region []. Donnelly et al. (2007) [] reviewed existing criteria for receptor selection with a multi-disciplinary team and concluded that receptor selection should include: relevance to project plan, prioritization in accordance with economic, social, and environmental significance, and the ability to identify conflicts with other environmental objectives for the region. Other authors have suggested using landscape vulnerability evaluations, resources of interest, or the selection of receptors based on the likelihood of impact during construction phases of the project or operation phases [,].

- Determination of impact likelihood and magnitude. This relies on the baseline conditions. Predicting impact likelihood and magnitude are some of the key tasks of EIA because these determine the significance of a particular impact. When possible, sensitivity analyses are done on these estimates, providing a basis for qualifying any expert input []. Canter and Sadler (1997) [] performed the most recent comprehensive review of impact analyses methods used in EIA, which to date has not been updated nor replicated in the literature. Methods ranged from basic analog project comparative methods to the development of environmental indices used to qualitatively compare pre-and post-project conditions, and the use of statistical models for air and water quality parameter predictions. However, they noted that the mathematical modeling techniques available at the time did not comprehensively describe the baseline conditions, nor post-project conditions, and that they were prohibitive in most instances due to the need for extensive data input and calibration []. Indeed, most impact predictions have relied on expert, yet predominantly, subjective opinions.

- Impact significance is determined by the magnitude, duration, and extent of the predicted impacts. However, it can also be subjective and intertwined with values and inputs from various stakeholders. An impact at a large regional scale may be considered insignificant, but at a smaller, local scale could be highly significant. There have been attempts to quantify significance [], but this requires appropriate statistical analysis of available data []. The matrix published in Leopold et al. (1971) [] that listed 8800 interactions as a result of project actions is still widely used today because it has the advantage of formalizing educated, but still subjective, reasoning []. They also noted that only a few of those 8800 interactions would have significant likelihood and magnitude.

- Mitigation. If impacts are found to be significant, mitigation measures must be proposed. Compensation is also an option when mitigation is deemed not possible and alternatives can be costed and compared. An “environmental management plan” is then developed to identify actions to be taken.

Nearing the end of the EIA process, results and recommendations are presented to the stakeholders in a variety of forms intended for different audiences. A critical step that must be observed is that this is presented not as a final decision but as a recommendation that monitoring and evaluation of project activities should continue. There is then a review of the study, which is sometimes, but not always, completed by an independent third party. The EIA process can however end here, but two additional steps may appear: first the addition of a long-term monitoring program, and second, a post-project audit may be done. These steps are intended to validate the initial conclusions of the EIA, but are rarely assessed in this context. These two steps, often recommended in the EIA documents, do not appear to be widely applied in practice, making any evaluation of the impact prediction impossible to perform.

4. How Does the EIA Process Compare in Different Nations?

The literature regarding the application of EIA globally is disparate and dated, however there do exist several studies that illustrate the challenges facing developed and transitioning nations. Briffett (1999) [] identified differences in both developed and transitioning countries where “there are considerable variations in the EIA systems used, particularly in relation to the scope (public or private), scale (national, local) and content (physical, biological and social parameters).” Lee and George (2000) [] described differences in the extent to which the guidelines were followed as due to broader issues, such as “… resources and administrative systems, social and cultural systems, and the level and nature of economic development.” Donnelly et al. (1998) [], produced the most comprehensive directory of the state of EIA across the world in 1998, and which to date there has not been another comprehensive review. However, other authors have examined differences in the state of EIA and SEA practices between various countries, only with a smaller scope, such as differences between two or three countries or the challenges in developing nations. They have found similar results as Donnelly, such as lack of studies to evaluate the application of guidelines and lack of scientific rigor in impact analyses [,,,,]. Donnelly et al. (1998) [], statements still definitively summarize the discrepancies between countries in the practical application of EIA via various legislative tools, guidance documents for EIA production, and the governmental authorities that are responsible for the decision-making resulting from the EIA. They note that “[…] where guidelines exist, they are often not used;” and interviews showed between 49–60% of policy makers, advisors, and consultants only occasionally used them []. Still, there have are very few studies on various guidelines, and this is an area that has been noted as lacking sufficient evaluation by UNEP []. In addition, Donnelly et al. (1998) [], and others have found that EIAs failed to use the best available science and that they reflected the needs of administrations rather than those of practitioners [,,].

A decade later Li (2008) [], writing for the Foundation for Environmental Security & Sustainability (FESS) and USAID, reported that EIAs throughout the developing world “fall short of international standards” and “[…] suffer from insufficient consideration of impacts, alternatives, and public participation. In a worst-case scenario, they are not conducted at all”. The author reported that the countries with the strongest EIA procedures are: USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the Netherlands [] (see Appendix A and Appendix B for details).

Example of the Nigerian Case

African countries are cited as particularly lacking in guideline instructions for EIAs, even if most nations have environmental legislation in place requiring EIAs; in practice, there seems to be no effective implementation [,,]. Nigeria is a case in point. Prior to 1970, agriculture was the primary economic activity in the country, then the oil industry burst on the scene []. Rapid urbanization and industrialization as a result of revenues from oil exploration led to increasing and unregulated environmental degradation. After the dumping of toxic waste in Koko Port in 1988, the country jumpstarted a series of environmental legislative policies, including the eventual requirement for an EIA []. The “knee jerk” legislative efforts led to the development of three EIA systems: the EIA Decree 86 (1992), the Town and Country Planning Decree 88 (1992) and the Petroleum Act (1969) [,]. Several evaluations of the state of EIA in Nigeria have concluded that the system duplicates efforts due to similar requirements found in these legislative acts: there are too many conflicts of interest among EIA governing authorities, there exist important oversights in the quality of execution at all stages, there is a severe lack of public participation at all stages, and deficiencies in the competence of EIA practitioners. These contribute to generally poor EIA study quality [,]. Specifically, there exists no code of conduct or certification for consultants. This can increase the potential for third-party consultants to evaluate impacts based on subjective criteria, with the outcome sometimes being minimized in favor of the project proponent. In addition, multi-disciplinary teams are rarely used and in most cases the practitioners are uni-disciplinary, usually with a degree in biology and some evaluation tools (such as Leopold’s matrix []), which are then rarely utilized in the process []. In essence, the impact analysis is limited to subjective guesswork by underqualified individuals hired by project proponents.

The World Bank Group has funded 14.2 billion Nigerian dollars since 1958 for several infrastructure projects in the country []. With the recent decease in oil market values, Nigeria has again turned to the African Development Fund and World Bank for more funding to boost infrastructure projects and buffer the national economy. Considering these funding sources and their need to hedge against risk, a quantitative impact and risk analysis in both private and public-sector projects would be highly desirable.

5. Criticisms of Existing Approaches: What Role for Science?

Comparative studies done on the state of EIA highlight numerous political, economic, legislative, administrative and, most pointedly, scientific weaknesses in the impact analysis itself. According to Cashmore (2004) [], there has been no standardized requirements for EIA practitioners, other than expertise in biology or ecology, but no certifications or other proof of expertise are required. This is still true today in a majority of countries. Training programs exist in most developed nations, but there are no requirements for their fulfillment to write the document [].

Many countries follow the EIA process described above (Section 3). Nonetheless, when Canter and Sadler (1997) [] examined EIA methodologies, they found that, while some EIA guidelines and directives do specify acceptable methods, in other places, it is left to the discretion of the practitioner [,,]. This creates a potential conflict of interest because the practitioner is, in many cases, being hired directly as a consultant by the project proponent or promoter. For instance, since the proponent wishes to have a cost-effective EIA, the practitioner can be pressured to rationalize a lower standard of analysis [,].

It is generally agreed within the EIA community, that quantifiable and predictive impact assessments are desirable, but lacking. Some authors have examined the role a more scientific method would play in the decision-making process of an EIA [,,]. Several authors have proposed a broader model for EIA which would serve to shift the focus to a substantive role—a change that would require using quantitative scientific approaches, statistically tested hypotheses, and verifications at each step of the process [,,,]. We believe that working toward an evidence-based and testable impact assessment is central to achieving this aim.

One recurring criticism is that impact predictions employ an informal method of cause and effect deduced from analogy and precedent without incorporating recent scientific advances [,,]. Morrison-Saunders [] interviewed experts in Western Australia and found that they had varying expectations for the role of science in EIA depending on the type of project, its location, and the stage of the EIA process. For example, most practitioners found more science/scientific analysis was involved in baseline and impact predictions than in the mitigation and monitoring stages. However, even the sampling methods for establishing baselines have been found unreliable in many instances. This concerns not just data collection, but also the definition and characterization of what a defensible baseline condition(s) is and the identification of suitable reference sites remain fundamental challenges when dynamic processes are involved []. In the EIA community, there seems to be a consensus regarding the need for quantification, but there is a lack of normalized practices that would incorporate and transmit such changes.

In 2015 Leung et al. [], examined how uncertainty was treated in EIAs. They found only 134 journal papers (published between 1970 and 2013) discussed uncertainty in impact assessments and the majority (75%) were published after 2005. One of the themes emphasized by these authors was that uncertainties regarding impact predictions were not fully disclosed and, therefore, not being included in the decision-making process. In 2006, Tennoy and Kvaerner [] examined 22 case studies and concluded that uncertainty regarding the limitations of predictions was not only not disclosed to decision makers, but also the underlying assumptions and input data quality were not discussed in EIA. We can only conclude that while the EIA community understands the limitations inherent in impact predictions, and critical information regarding impact, risk, and uncertainty are apparently not being communicated sufficiently, or at all. This is not necessarily the fault of the EIA practitioner, but can be limited by the amount of funding allocated to data gathering efforts. Conventional methods of data collection, particularly when confronted with large spatial and long temporal scales, are very costly. Consequently, when confronted with expensive monitoring efforts developers tend to keep these funds for the project itself, rather than allocate for further environmental investigation.

6. What about Risk Assessment?

While most EIAs evaluate a project’s possible alternative impacts, surprisingly they do not examine the inherent risks involved with various specific activities [,]. Risk is generally defined as the “likelihood that a harmful consequence will occur as the result of an action or condition” []. The risk assessment process involves analyzing agents and exposure potential, characterizing the potential for adverse effects, defining uncertainties, generating options to minimize risks identified, and communicating information about these risks. This process provides a technical basis for evaluating current environmental conditions and forecasting future conditions under selected scenarios []. Advanced risk assessments can incorporate large amounts of technical information and even societal values.

The separation of risk analysis from the EIA does not make economic sense for project proponents who need to have quantifiable predictions of risks. Today both the risk and impact assessment process are a component of corporate and institutional lending. Lending institutions, such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and regional banks have a strong incentive to understand the environmental implications of their lending decisions. If the EIA considers only project level actions and does not examine other activities (either already existing in the area, or subsequent projects that may be a result from this project in the future) the sustained and comprehensive impact on the environment is neglected. Thus, the risks of missing the real environmental impact of such an operation are unappreciated by decision makers.

In addition, there are other risks that many times are not addressed in this “project development stage” approach to EIA. For example, in fracking and offshore oil drilling, many times the transport risks of such resources are neglected altogether []. Do we need to consider in a risk analysis the possible impacts of the transport of petroleum during shipping, as in the Exxon Valdez instance? Should the impact(s) of a possible well leak, as in Deep Water Horizon, be included? We note that the Deep-Water Horizon project was given a “categorical exemption” under NEPA in the US and was not required to even produce an EIA []. This type of impact would not likely have been evaluated in the EIA, as it is not considered a “stage” of project development.

Finally, risks are not static concepts but evolve as societies, technologies, and environments change. For example, today we could add the general category of climate change and all accompanying effects, such as: increasing insect damages to crops, increasing severe weather events, rising sea levels…etc. Other “new” risks not often mentioned are: acid rain, ozone depletion, urban sprawl, the effects of genetically engineered organisms, and radioactive waste disposal []. Public concern about the state of the natural environment poses risks for the state of a funding institution’s lending portfolio, which has generated a need for more precise and quantitative analyses of potential impacts that are linked directly to risk.

7. A Roadmap to Change: System-Based Environmental Impact Assessment (SBEIA)

It is the assertion of this viewpoint that EIA remains a strong foundational tool. It has the advantage of already being in place, but there needs to be discussion about how to move towards a statistically relevant impact and risk analysis that can be applied in both developed and transitioning nations. We argue that this is necessary in all environments, but particularly in the marine realm, because of the nature of oceanic environments that make containing negative outcomes (like contaminant release or alien species or pathogens) extremely difficult and costly. In addition, the complications in Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (ABNJ) add another difficult element to impact and risk assessments. Therefore, a new approach has become urgent.

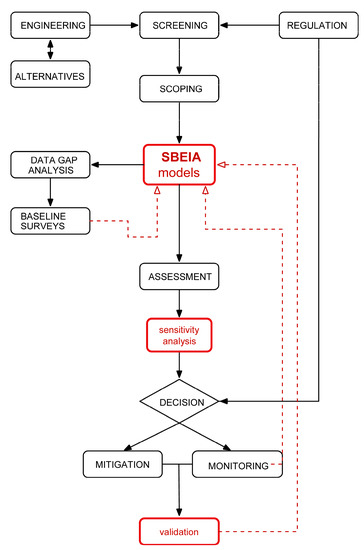

We therefore propose a new approach to EIA, that we call a System-Based EIA (SBEIA; Figure 2), which is inspired by the technical definition of an “Ecosystem” within ecological theory. From this point of view, the fundamental property of an ecosystem is that all organisms find the condition for their co-existence in their environment (both abiotic and biotic). This means that the model must encompass in the same conceptual framework living organisms, ecological interactions, and physical factors (including environmental conditions and resources), ensuring that living organisms can persist under the defined “environmental” conditions. The framework moves System-Based modelling, sensitivity analyses, and validation to the center of the IA process (Figure 2), but does not guaranty an internal condition for the coexistence of living organisms, rather defined general conditions for their presence within the EIA domain. It aims to provide policy makers, funding institutions, companies, and the public a comprehensive, data-driven picture of the eco-systemic, economic, and societal costs and benefits of a particular project design, alternative scenarios, as well as daily operations. In addition, we assert that the adoption of an SBEIA type framework would constitute an economic rationality for project proponents and lenders. This could provide an added impetus for more accurate impact assessments in transitioning nations, where large, international institutions, such as the IMF and World Bank fund many infrastructure projects.

Figure 2.

System-Based EIA (SBEIA) Workflow Chart.

Earlier in 2017, the authors published a technical article [] defining the SBEIA method both theoretically and technically. This article outlines the mathematical modelling theory of the SBEIA method as well as the statistical analyses used for determining impact thresholds. This article also used as a case study an actual development project in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea, and applied the SBEIA method. This case study provided quantitative results of impact on primary productivity based on the published data. The following text summarizes the theoretical methods and application of the SBEIA, and the implications for EIAs on a global scale.

The SBEIA framework we propose means implementing a statistically rigorous framework to evaluate project impacts []. The SBEIA process can help establish what the most significant factors and processes are in the surrounding environment by modeling, to elucidate the sensitivity of certain variables. The SBEIA process starts with understanding the physical-chemical changes caused by a project, associating those changes with ecosystem function changes, and then applying those changes to understanding impacts on receptors. SBEIA promotes data input under different project scenarios and at different stages, making the methodology dynamic, repeatable and adaptable (Figure 2). For instance, new engineering solutions, mitigation actions, and other new survey and monitoring data can provide a continuous input into the model and re-assessment of the results and regulatory actions and financial assessments can be incorporated into the process to ensure stakeholder goals are met. A comparison between the conventional EIA framework and the proposed SBEIA method is summarized below in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparing Conventional and System-Based Environmental Impact Assessment (SBEIA).

For the SBEIA framework to become truly quantitative, it must be built upon a numerical and statistical framework, where variables are allowed to interact and manipulate one another, and the resulting states can be expressed numerically. SBEIA is based on a modeling platform that can predict the physical processes that dominate an ecosystem and their associated impacts on the chemical and biological spheres within the system for both the project area and its surroundings. Allowing the foundation of the EIA to evolve from qualitative screening and conceptualization to a numerical and statistically driven approach gives the SBEIA the power to be quantitative in both the prediction of impact, and the level of confidence of the predictions. SBEIA provides for the precise repetition of the methodology. In more qualitative EIA methods, the determination of receptors and impacts has the potential to be subjectively chosen based on the inherent biases of a client, consultant, agency, and/or cultural importance. An SBEIA approach rooted in mathematical relationships enforces a clear methodology that can be recreated by another user.

An SBEIA modelling framework is one that attempts to model the entire system, and not isolate individual receptors. In doing this, one gets a better understanding of the physical and chemical processes that drive the ecosystem they are working in, and how a proposed impact will alter these processes. Identifying the changes in the natural processes of an ecosystem highlights the fundamental drivers of change in an ecosystem and to important receptors. Too often, the EIA process is composed of unidirectional conceptual models that state, for example, the introduction of a Stress A will have an impact on Receptor X. Conversely, the SBEIA approach introduces a network of variables and receptors that are linked numerically in a rigorous statistical framework. When introducing the same stress on the SBEIA model system, the impact is propagated throughout the network providing, in theory, a more accurate evaluation of impact both to the entire system and for specific receptors.

Another alternative to conventional EIA is the Life Cycle Impact Assessment method, which is a part of the more general Life Cycle Analysis framework. Life Cycle Analysis attempts to encompass the entire set of processes and resources that the project will exploit from the beginning to the end of the project. Thus, Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA) formalizes the environmental impact of the successive steps of a project during its lifetime, from implementation to decommissioning. It is, therefore, project oriented and differs from SBEIA, which, on the contrary, is ecosystem oriented, focused on the dynamics of the ecosystem processes. It therefore, does not identify explicitly a beginning or end as the LCIA implies, but implies the project activity is inserted into an existing set of dynamic processes.

In addition, the LCIA rests on an information tool called the Life Cycle Inventory (LCI). The LCI aims to describe exhaustively all components of the project realization, and their effects on the environment at each step, including potential disturbances. This approach is modelled after concepts of organismal life cycle history used in biological research, and suffers from the same weakness regarding ecological analyses: is does not replace the project (or organism) within the ecological system in which it is imbedded, but instead attempts to identify various threats at different stages or steps and their possible consequences on public health []. Absence of adequate data to describe in identical, or even relevant, detail all the processes, transformations and consequences encountered or implicated during a project can render this approach ineffectual. Whereas the process-oriented modelling of SBEIA permits representation of well-known ecosystem processes in scenarios even when little or no data are available.

Finally, in the SBEIA framework, baselines and reference conditions assume a central role. All impacts are determined relative to baseline conditions. These can be environmental variables such as sediment types, current flow, wind velocity, the biomass of primary producers in the system, chemical constituents, and/or temperature. For instance, if a small bay or inlet has been showing increasing signs of oxygen depletion due to harmful algal blooms in recent decades, this trend for a reduction in dissolved oxygen content needs to be considered as an overall trend in the system, and baseline data collection and proceeding impact analyses need to take this into account. The establishment of accurate baseline parameters in the system is critical to establishing whether an impact is statistically significant. The differences in the outcome on the receptor can then be evaluated for statistically significant changes. This adds an element of scientifically rigorous analyses not previously available in traditional EIA practices. It also provides a method to evaluate how sensitive a receptor is to changes, because the greater the change, the more sensitive the receptor is to change [].

Some Suggested Changes to Current Practice

The determination of projects that require an EIA is usually decided by the country’s governing authority or, in some cases, by corporate standards. However, since many of these projects obtain funding from banking institutions, even if the governing authority is vague, it would behoove the project proponent and lender to at least consider the benefits of developing a quantitative EIA to protect lender funds. This could be encouraged during the screening phase, with input from both the governing authority and the proponent.

The scoping phase would then begin after the first modelling results are communicated. Stakeholders and the public would then decide which aspects of the project should be focused upon. A system predictive modeling approach can be adapted in the scoping phase, exploiting existing datasets for parameter estimates. This becomes an exploratory tool for determining where the focus of the EIA should be headed: i.e., if an expert suggests there might be a reduction in primary producers expected, this decrease could be incorporated into a scenario that explores how the stock of a locally fished marine species could be affected, which could put local industries at risk. The outcomes would also be used to identify critical data gaps and refine additional data collection efforts.

The SBEIA process then would continue based on the scoping results. In the case of all projects, and specifically in marine projects, geotechnical data (e.g., sediment structure, bathymetry surveys, etc.) will be required for engineering the proposed structure or structures. The EIA team, after scoping, can either use this data as is, or suggest expanding data collection to minimize impact (and associated risk) for the project proponent and lenders.

After baselines are determined, EIA practitioners can then quantify impacts under different project scenarios, and may incorporate the socio-economic activity as a driver of change [], impacts on other ecosystem parameters, and even landscape-wide impacts could be examined. Project alternatives can then be assessed, thereby providing decision makers with quantifiable data to base project decisions upon and to find the least impactful scenarios, or at least establish “tradeoffs”. For example, if a specific project alternative is found to impact a certain amount of biomass of primary producers, the modeling of that impact would show the extended effects on other ecosystem variables due to this change. The predictive modeling method can give the project proponent valuable information regarding at what point the magnitude of change would have costly effects. This makes the proponent and government/regulatory agency aware of when the proposed activity could generate more impact than is cost effective for them and possibly unsustainable for the ecosystem and local economies. These same modeling tools can be utilized in the mitigation and monitoring stages of EIA to evaluate the effectiveness of mitigating measures.

8. Conclusions

This viewpoint contends that the quantification of impacts and risks to ecosystems can be achieved with an SBEIA approach. This approach benefits decision makers and stakeholders, as it would utilize data-driven modeling of the effects of project activities to predict impacts in terms of a probability with a quantifiable error [].

With recent advances in survey technologies, particularly for the marine environment, such as autonomous vehicles and remote sensing devices, the collection of relevant temporal and spatial environmental data for baseline analysis and impact assessments has become more accessible and affordable. Much of the data required for establishing baseline conditions for the EIA is, many times, collected by the project proponent pre-construction to assist with engineering, especially in marine habitats. In this age of big data, EIA needs to adapt to utilize this data in a statistically rigorous manner. The SBEIA approach, as described further in this publication, will move the aim of EIA from its proximate goal of evaluating social, economic, and ecological impacts from project activities, to its substantive goal of sustainable development. This quantitative framework aims to provide the ability to identify data gaps, design baseline surveys with proper statistical power, and plan effective monitoring for model validation. This system-based modeling can be iteratively run as more accurate measurements are collected, and the company can enhance the accuracy of impact and risk predictions of various scenarios and minimize them and their costs. This approach allows for the simulation of engineering alternatives, the assessment of the success of mitigation, and predictions that are supported by Bayesian statistics that may be required for social or regulatory compliance [].

We acknowledge that the implementation of these changes within the industry, albeit readily possible and an improvement on the current state of EIA, will still require shifts in how regulatory entities communicate and a commitment from political entities. The science and technology is available, yet we acknowledge that political issues can present blockages, as evidenced in our comparative review of EIA for various countries. However, the power of a quantitative EIA is its ability to relate to risk assessments and the associated financial implications, and it is our assertion that this aspect of our viewpoint can create the needed economic incentive for companies, stakeholders, and governments to pursue this methodology. This is particularly applicable to transitioning nations, as infrastructure improvement projects rely on funding from international banks, and these funding institutions would benefit from a thorough SBEIA approach.

EIA remains a valuable mandated tool that is used to evaluate project activities, alternatives, and environmental impacts. This viewpoint presents the argument that current technologies (hydrodynamic computer modeling, remote sensing technologies, autonomous survey technologies) allow EIA practitioners to incorporate a quantitative system-based modeling approach. This will shift the perspective from EIA from a decision-making tool to something that can be used to quantitatively predict impacts, and possible changes to entire systems, including socioeconomic factors as drivers of change. Risk analyses can be easily integrated by incorporating accident scenarios. Accurate data can be collected and shared in the scoping and screening phases to focus EIA.

The shift to this technological and quantifiable methodology can be taught to practitioners and funded by either project proponents or lenders. It is our assertion that the integration of this system-based modeling to quantify impacts and risks into EIA is economically feasible and will not only move EIA towards it “substantive” goal of preserving ecosystem functions, but will also be financially beneficial to the private and public sector.

Acknowledgments

Participation of Jennifer Coston-Guarini was supported by the “Laboratoire d’Excellence” LabexMER (ANR-10-LABX-19) and co-funded by a grant from the French government under the program “Investissements d’Avenir”.

Author Contributions

Jeff Wilson, Shawn Hinz, Jennifer Coston-Guarini, and Jean-Marc Guarini all contributed to the conceptual structure of the SBEIA method. Jeff Wilson and Shawn Hinz wrote the majority of the text and provided project-specific examples from professional experience. Jennifer Coston-Guarini provided extensive input and editing of the manuscript, as well as the historical development of the EIA method and its implications. Jean-Marc Guarini designed the technical SBEIA model, and provided the technical and mathematical guidance. Camille Mazé contributed to the social and political context of the EIA discussion on a global scale. Laurent Chauvaud as director of the BeBest program provided the overall scientific guidance of the manuscript, research support, and provided overall marine ecological guidance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Comparison of EIA practices in the US and the EU [].

Table A1.

Comparison of EIA practices in the US and the EU [].

| Actions | US [] | EU [] |

|---|---|---|

| Types of activities requiring EIA | Public projects that are determined to have a significant impact on the environment require an EIA. However, public projects include any activity financed, assisted, or regulated by a federal agency, many private projects are subject to EIA. Does not apply to policies or programs. | Public and private projects that are likely to have a significant impact. Does not apply to policy or programs, but new SEA directive requires that. Annex 1 projects: mostly large infrastructure projects. Annex II projects: projects that Member states may require EIA and may exempt “in exceptional cases”. National defense projects and projects “the details of which are adopted by a specific act of national legislation” are not covered by the EC EIA directive. |

| Screening | Each federal agency has a list of projects that have been shown to not have significant impacts. For all other projects, a preliminary assessment is performed to determine if EIA is required. | Projects subjected to screening by category. Annex I require EIA, Annex II only require one if Member state determines it is necessary. |

| Who conducts EIA? | NEPA requires federal agency to conduct. Agency may hire consultants. Project proponents are forbidden to partake in the process of who will conduct the EIA. They can prepare preliminary assessments, but EIA is not prepared by project proponents | EC directive requires the project proponent to prepare the EIA, whether that be private or public. |

| Who pays for EIA? | Federal agencies are authorized to recover costs from project proponents, but only a minority of agencies have done so. Therefore, the financial burden falls on the taxpayer. | No guidance in directive. It is left up to Member States to decide. |

| When does EIA begin? | Earliest possible time in project development. | Not specified. |

| Scoping | Public is notified of intent to produce EIA and participation is encouraged in scoping. Agency with jurisdiction determines final scope. Needs to consider “connected actions, cumulative actions, and similar actions”. Also, direct and indirect impacts, and cumulative impacts | Directive does not discuss scoping, but does give some guidance: project description, site description, project size and design, measure used to reduce impacts, and data required. Member States may require more specific information. Alternatives must be analyzed also. |

| What types of impacts? |

| Directive simply states: “identify, describe, and assess direct and indirect impacts on human beings, flora, fauna, soil, water, air, climate, landscape, and the interaction between them, and material assets and the cultural heritage”. |

| Alternative analysis required? | Impacts of all reasonable alternatives must be analyzed | Member states decide whether alternative analysis may be included. If so, the developer decides alternatives to be discussed. |

| Mitigation measures? | Document must include mitigation measures, but agency is not required to adopt them, and, if not, they must explain why not. If adopted, lead agency must ensure they are enacted. | EIA must contain a description of the measures envisaged in order to avoid, reduce and, if possible, remedy significant adverse effects. |

| When must EIA be completed? | No action can be taken until 30 days after publication of EIA and public notification, filing with EPA. | The EC Directive does not specify when the EIA document must be completed, but states that projects must be made subject to EIA before consent to proceed with the project is given. |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Comparing EIA in other developed nations.

Table A2.

Comparing EIA in other developed nations.

| Actions | Canada [,] | Australia [,,] | New Zealand [] | Netherlands [,] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types of activities | Government and private projects, even projects outside the country that are funded by the government. | Government and private project requiring government leases and/or permits. | Government and private projects requiring leases and/or permits. | Government and private projects requiring permits and/or leases. Included EIA for plans in 2006 []. |

| Screening | Government agency conducts screening process. | Government agency guides project proponent for screening. More recently private industry and municipalities have a screening process, sometimes termed a Preliminary Environmental Assessment (PEA) in order to reduce the need for an EIA early on in the process. A limitation of this is that these documents are not required to be reviewed by government and the public is not involved. | Government conducts screening | Ministry of Infrastructure and the Environment regulates and drafts guidance. There is either Direct Obligation as determined by the competent authority, or a decision for a voluntary EIA by the project proponent. |

| Who conducts EIA? | Agency performing or funding project. For private projects, proponent is responsible. Conflict of interest not addressed. | Agency if it is a government project. Project proponent if it is a private project. EIA qualification not addressed in law. Conflict of interest not addressed. | Project proponent with or without a consultant. EIA qualifications not addressed in law. Conflict of interest not addressed in law. | Proponent announces intention to produce EIA, public consultation during scoping, competent authority advises the process to ensure guidelines are followed. Conflict of interest not addressed in law. |

| Who pays for EIA? | Participant funding available for limited financial support to non-profits, individuals, and Aboriginal groups. Cost recovery regulations are in place to recover costs from proponent. | Cost Recovery under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 which provides that ‘those who create the need for regulation should incur the costs. | Not mandated by law, but usually project proponent. Bond may be required by government discretion. | Project proponent pays for EIA. If government project or major government funding is provided, the government agency funds EIA. |

| When does EIA begin? | Very early on when screening determines an EIA required. | After screening by agency determines significant impact. | After screening by agency determines significant impact. | Begins in scoping phase after EIA is announced by Competent Authority. |

| Scoping | Agency conducting project or proponent. Public comments are encouraged during scoping. | Scoping document (ESD) prepared by project proponent with guidance of govt may or may not be presented to public for a two week review period after it is completed. | Done by project proponent with input from public comment. | Public notice published by Competent Authority. Proponent begins scoping with public participation. Guidelines for the specific project are issued by the Competent Authority and consultation with the independent Netherlands Commission for EIA. |

| What types of impacts? | Direct, indirect, cumulative, economic, social, cultural, and regional impacts. | Direct, indirect, cumulative, economic, social, cultural, and regional impacts. | Direct, indirect, cumulative, economic, social, cultural, and regional impacts. | Direct, indirect, cumulative, economic, social, cultural, and regional impacts. |

| Alternative analysis required? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Mitigation measures? | Yes and monitoring where impacts have been identified | Yes and monitoring where impacts have been identified | Yes and monitoring where impacts have been identified. | Yes and monitoring where impacts have been identified. |

| When must EIA be completed? | Within 365 days, and 24 months with review panel. | Unique to each proposal. | No specified. | Not specified for screening. No official requirement for approval of scoping document, only recommendations. The National Commission for Environmental Assessment must publish advisory report on the quality of the EIA and get public comment within 6 weeks, Comments must be responded to within 3 weeks. |

| Governing authority | Government Agency or a Review panel of individuals appointed by Minister of the Environment. | Government Agency. In Western Australia, the Department of Environment | Governing agency. | Ministry of Infrastructure and the Environment |

References

- Holder, J. Environmental Assessment: The Regulation of Decision Making; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 9780199207589. [Google Scholar]

- Coston-Guarini, J.; Guarini, J.-M.; Hinz, S.; Wilson, J.; Chauvaud, L. A roadmap for a quantitative ecosystem-based environmental impact assessment. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2017, 74, 2012–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasson, J.; Therival, R.; Chadwick, A. Introduction to Environmental Impact Assessment, 4th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-0415664707. [Google Scholar]

- Wathern, P. Environmental Impact Assessment: Theory and Practice, 4th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2004; ISBN 9780415078849. [Google Scholar]

- International Association of Impact Assessment (IAIA). What Is Impact Assessment? Available online: http://www.iaia.org/uploads/pdf/What_is_IA_web.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2017).

- Thompson, M. Determining Impact Significance in EIA: A Review of 24 Methodologies. J. Environ. Manag. 1990, 30, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petts, J. (Ed.) Handbook of Environmental Impact Assessment: Volume 2: Impact and Limitations; John Wiley & Sons: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0-632-04771-0. [Google Scholar]

- Jay, S.; Jones, C.; Slinn, P.; Wood, C. Environmental impact assessment: Retrospect and prospect. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2007, 27, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, D. The need for EIA theory-building. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 1997, 17, 79–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinemann, A. Improving alternatives for environmental impact assessment. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2001, 21, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arts, J.R. The effectiveness of EIA as an instrument for environmental governance: Reflecting on 25 years of EIA practice in the Netherlands and the UK. J. Environ. Assess. Policy Manag. 2012, 14, 1250025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozema, J.; Bond, A.J. Framing effectiveness in impact assessment: Discourse accomodation in controversial infrastructure development. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2015, 50, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopold, L.; Clarke, F.E.; Hanshaw, B.B.; Balsey, J.R. A Procedure for Evaluating Environmental Impact; Geological Survey Circular 645; U.S. Department of Interior: Washington, DC, USA, 1971. Available online: https://eps.berkeley.edu/people/lunaleopold/(118)%20A%20Procedure%20for%20Evaluating%20Environmental%20Impact.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2017).

- Lawrence, D.P. PROFILE: Integrating Sustainability and Environmental Impact Assessment. Environ. Manag. 1999, 21, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Improving the Practice of Impact Assessment. Available online: http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/ffu/evia/EVIA_Policy_Paper.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2017).

- Fischer, T.B. Strategic envrionmental assessment in post-modern times. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2003, 23, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, K. Regulatory Impact Assessment and sustainable development: Towards a common framework. Eur. J. Risk Regul. 2010, 1, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, S.; Fischer, T. Towards sustainability: Is integrated appraisal a step in the right direction? Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2007, 25, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaza, H.B. Environmental Impact Statement and Strategic Environmental Assessment: Towards and Integrated Approach; United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP): Geneva, Switzerland, 2004; ISBN 92-807-2429-0. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.C. Environmental Impact Assessments in Developing Countries: An Opportunity for Greater Environmnetal Security; Working Paper No. 4; United States Agency of International Development (USAID), Foundation for Environmental Security & Sustainability (FESS): Washington, DC, USA, 2008. Available online: http://research3.fit.edu/sealevelriselibrary/documents/doc_mgr/470/Global_EIAs_in_Developing_Countries_-_Li_2008.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2017).

- Wright, G. Strengthening the role of science in marine governance through environmental impact assessment: A case study of the marine renewable energy industry. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2014, 99, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujikura, R.N. Factors leading to an erronous impact assessment: A postproject review of Calaca power plant, unit two. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2001, 21, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, A.; Jones, M.; O’Mahony, T.; Bryne, G. Selecting environmental indicator for use in strategic environmental assessment. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2007, 27, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, D.R.; Canter, L. The Use of Environmental Indicators for Impact Assessment in Compliance with the National Environmental Policy Act; Nuclear Regulatory Commission: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2008. Available online: https://www.nrc.gov/docs/ML0814/ML081410838.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2017).

- Bojórquez-Tapia, L.A.; Sanchez-Colon, S.; Florez, A. Building consensus in environmental impact assessment through multicriteria modeling and sensitivity analysis. Environ. Manag. 2005, 36, 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canter, L.; Sadler, B. A Tool Kit for Effective EIA Practice-Review of Methods and of Methods and Perspectives on Their Application: A Supplementary Report on the International Study of the Effectiveness of Environmental Impact Assessment; International Association for Environmental Impact Assessment: Norman, OK, USA, 1997; Available online: http://www.iaia.org/pdf/Training/SRPEASEIS01.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2017).

- Pavlickova, K.; Monkia, V. A method proposal for cumulative environmental impact assessment based on the landscape vulnerability evaluation. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2015, 50, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briffett, C. Environmental impact assessment in Southeast Asia: Fact and fiction? Geology 1999, 49, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.; George, C. Environmental Assessment in Developing and Transitional Countries: Principles, Methods and Practice; World Scientific Publishing Co., Inc.: Singapore, 2000; ISBN 978-0-471-98557-0. [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly, A.; Dalal-Clayton, B.; Hughes, R. A Directory of Impact Assessment Guidelines, 2nd ed.; International Institute for Environment and Development: Nottingham, UK, 1998; Available online: http://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/7785IIED.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2017).

- Stampe, J.W. Lessons Learned from Environmental Impact Assessments: A Look at Two Widely Different Approaches—The USA and Thailand. J. Transdiscipl. Environ. Stud. 2009, 8, 3. [Google Scholar]

- El-Fadl, K.; El-Fadel, M. Comparative assessment of EIA systems in MENA countries: Challenges and prospects. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2004, 24, 553–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, C. Environmental impact assessment in developing countries: An overview. In Proceedings of the Conference on New Directions in Impact Assessment for Development: Methods and Practice, Manchester, UK, 24–25 November 2003; EIA Centre, School of Planning and Landscape, University of Manchester: Manchester, UK, 2003. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/3420793/Environmental_impact_assessment_in_developing_countries_an_overview (accessed on 4 June 2016).

- Chaker, A.; El-Fadl, K.; Chamas, L.; Hatjian, B. A review of strategic environmental assessment in 12 selected countries. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2006, 26, 15–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Environmental Impact Assessment Training Resource Manual, 2nd ed.; UNEP: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002; Available online: https://unep.ch/etb/publications/EIAman/IntroManual.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2017).

- Kakonge, J.O. Environmental Planning in Sub-Saharan Africa: Environmental Impact Assessment at the Crossroads; Working Paper #9; Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies: New Haven, CT, USA, 2006; Available online: https://environment.yale.edu/publication-series/documents/downloads/v-z/wp_9_africa_eia.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2017).

- Nwokeji, G. The Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation and the Development of the Nigerian Oil and Gas Industry: History, Strategies and Current Directions; James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy, Rice University: Houston, TX, USA, 2007; Available online: https://www.bakerinstitute.org/media/files/page/9b067dc6/noc_nnpc_ugo.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2017).

- Environmental Impact Assessment in Nigeria: Regulatory Background and Procedural Framework. Case Study 7. UNEP EIA Training Resource Manual. 2002. Available online: https://www.iaia.org/pdf/case-studies/EIANigeria.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2017).

- Nwoko, C.O. Evaluation of Enivornmental Impact Assessment System in Nigeria. Greener J. Environ. Manag. Public Saf. 2013, 2, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olokesusi, F. Legal and institutional framework of environmental impact assessment in Nigeria: An initial assessment. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 1998, 18, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunba, O.A. EIA systems in Nigeria: Evolution, current practice and shortcomings. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2004, 24, 643–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. Projects and Programs. 2017. Available online: http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/nigeria/projects (accessed on 27 April 2017).

- Cashmore, M. The role of science in environmental impact assessment: Process and procedure verses purpose in the development of theory. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2004, 24, 403–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.K. Environmental impact assessment: The state of the art. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2012, 30, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, R. A note on the use of the analytic hierarchy process for environmental impact assessment. J. Environ. Manag. 2001, 63, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Percival, R.V.; Schroeder, C.H.; Miller, A.S.; Leape, J.P. Environmental Regulation: Law, Science, and Policy, 6th ed.; Wolters Kluwer Law & Business: New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-1454822288. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison-Saunders, A.J. EIA Practitioner Perceptions on the Role of Science in Impact Assessment. In Proceedings of the 21st Annual Meeting of the IAIA’01 Impact Assessment in the Urban Context Conference, Caragena, Columbia, 26 May–1 June 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, W.; Noble, B.; Gunn, J.; Jaeger, J.A.G. A review of uncertainty research in impact assessment. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2015, 50, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennoy, A.; Kvaerner, J. Uncertainty in environmental impact assessment predictions: The need for better communication and transparency. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2006, 24, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suter, G.W., II. Ecological Risk Assessment in the United States Environmental Protection Agency: A Historical Overview. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2008, 4, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardenas, M.L. Environmental Risk Assessment (EnRA); United Nations Environment Programme Division of Technology, Industry and Economics: Paris, France, 2017; Available online: http://www.unep.or.jp/ietc/publications/techpublications/techpub-14/1-EnRA1.asp (accessed on 3 July 2017).

- Gromley, A.; Pollard, S.; Rocks, S. Guidelines for Environmental Risk Assessment. Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs; Cranfield University: Bedfordshire, UK, 2011.; Available online: http://www.fwr.org/WQreg/Appendices/Green_Leaves_3_pb13670-green-leaves-iii-1111071.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2017).

- Meng, Q.S. Distance: A critical aspect for environmental impact assessment of hydraulic fracking. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2014, 1, 124–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilperin, J.U.S. Exempted BP’s Gulf of Mexico Drilling from Environmental Impact Study. Available online: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/05/04/AR2010050404118.html (accessed on 5 May 2017).

- Kasperson, J.X.; Kasperson, R.E. Global Environmental Risk; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 92-808-1027-8. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y.H.; Ng, S.T.; Kumaraswamy, M.M. Critical analysis of the life cycle impact assessment methods. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2016, 14, 879–890. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency. Basics of Environmental Assessment. 2016. Available online: http://www.ceaa.gc.ca/default.asp?lang=en&n=B053F859-1#ceaa03 (accessed on 27 June 2016).

- Government of Canada. Canada Gazette. 2012. Available online: http://www.gazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p2/2012/2012-07-18/html/sor-dors147-eng.html (accessed on 4 February 2017).

- Thomas, I. Impact Assessment in Australia: Theory and Practice, 6th ed.; The Federation Press: Annandale, Australia, 2015; ISBN 978-1-86287-945-4. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Govenment: Department of the Environment. Cost Recovery under the Environment Protection and Biodiveristy Conservation Act 1999. 2016. Available online: http://www.environment.gov.au/epbc/cost-recovery (accessed on 12 December 2016).

- Environmental Protection Authority Western Australia. Environmental Assessment Guidelines for Scoping Proposal. Available online: http://www.epa.wa.gov.au/sites/default/files/Environmental_scoping_document/Cooljarloo%20West%20ESD%20300813.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2016).

- ELAW. EIA Country Report for New Zealand. 2016. Available online: http://eialaws.elaw.org/eialaw/new-zealand (accessed on 20 June 2016).

- Netherlands Commission for Envrionmental Assessment. Netherlands EIA Profile. 2016. Available online: http://www.eia.nl/en/countries/eu/netherlands/eia (accessed on 28 June 2017).

- Koornneef, J.F. The screening and scoping of Environmental Impact Assessment and Strategic Environmental Assessment of Carbon Capture and Storage in the Netherlands. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2008, 28, 392–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).