Mechanization of Conservation Agriculture for Smallholders: Issues and Options for Sustainable Intensification

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Mechanization of CA

2.1. Power Sources and Tasks to Be Mechanized

- Retention of crop residues for soil cover. Soil tillage is restricted to the rip lines where the crop is to be sown.

- Shallow (hoe) weeding to avoid major soil disturbance. Rip lines are first opened in the dry season, they will then concentrate the first, light, rains and facilitate the second ripping pass at the required depth.

- Crops are sown with the first effective rains.

- Crop rotations are practised with the inclusion of nitrogen-fixing legumes and other crops such as cotton and sunflower.

- Inter-row ripping of the legume crops in the rotation when the soil is still moist can mean that preparations are well on schedule for planting the next grain crop in the coming rainy season.

2.2. Availability of Mechanization

| Equipment | Price (USD) |

|---|---|

| Jab planter for seed and fertilizer (Fitarelli) | 40 |

| Animal-drawn, single-line, long-beam no-till planter and fertilizer (Fitarelli) | 500 |

| Tractor-mounted 3-row, no-till planter and fertilizer (Fitarelli) | 7000 |

| Animal-drawn 2-row no-till planter and fertilizer (also adaptable to 2WTs) (Fitarelli) | 2600 |

| Tractor-mounted 5-row no-till planter and fertilizer (Fitarelli) | 10,000 |

| Chinese-made 10 hp 2WT | 1000 |

2.3. Creating Demand for Mechanization

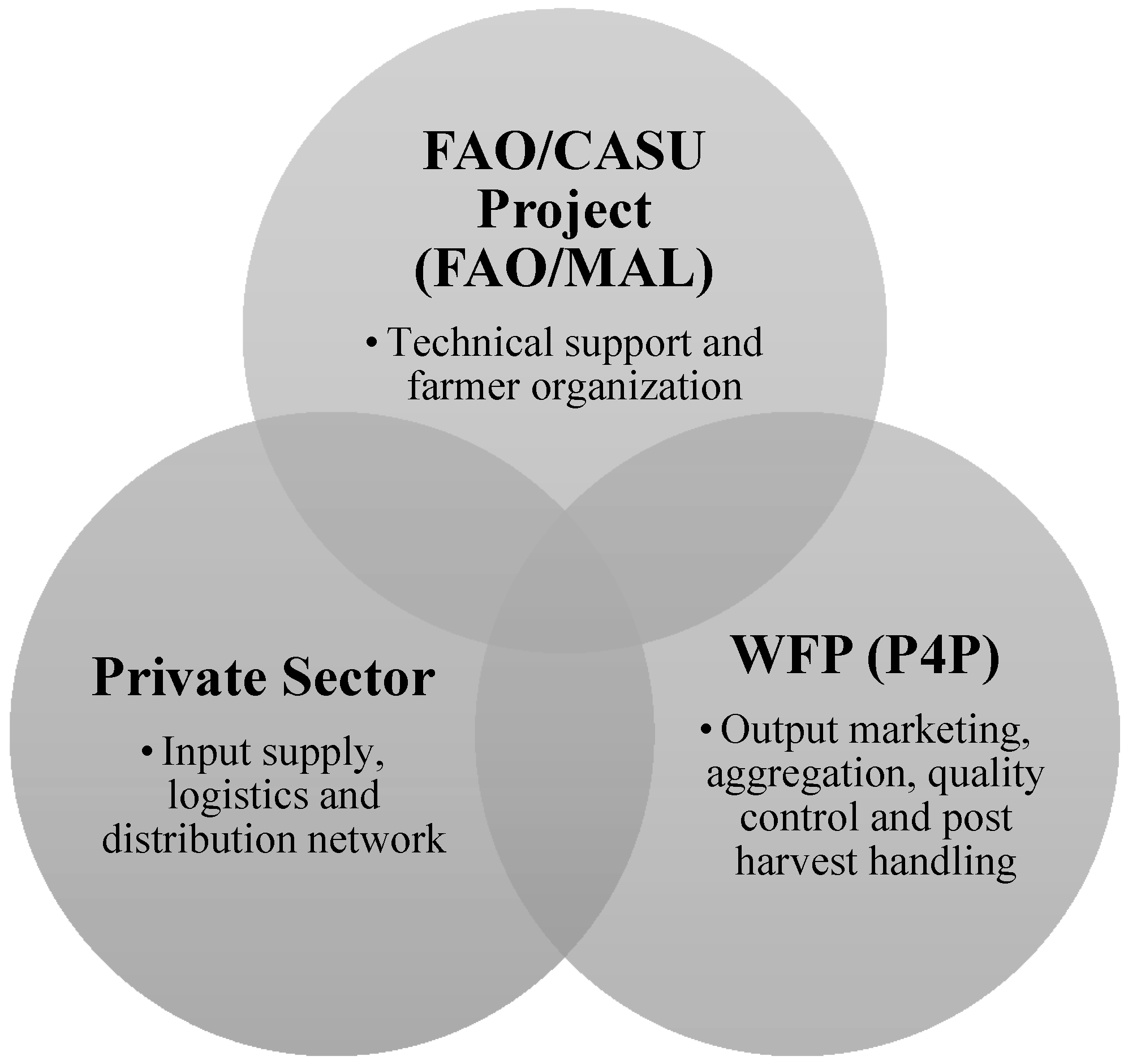

2.4. CA Mechanization Supply Chain

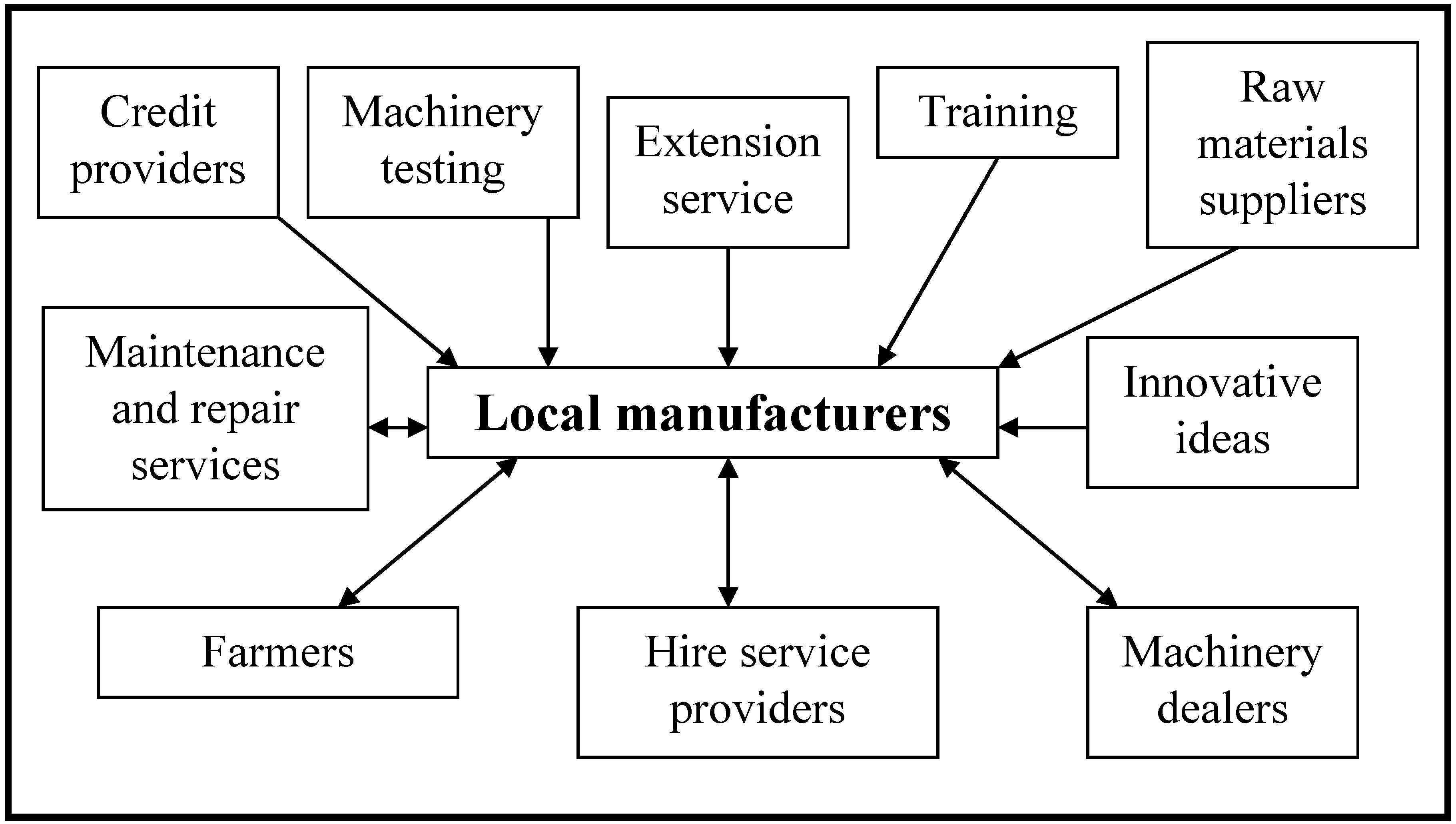

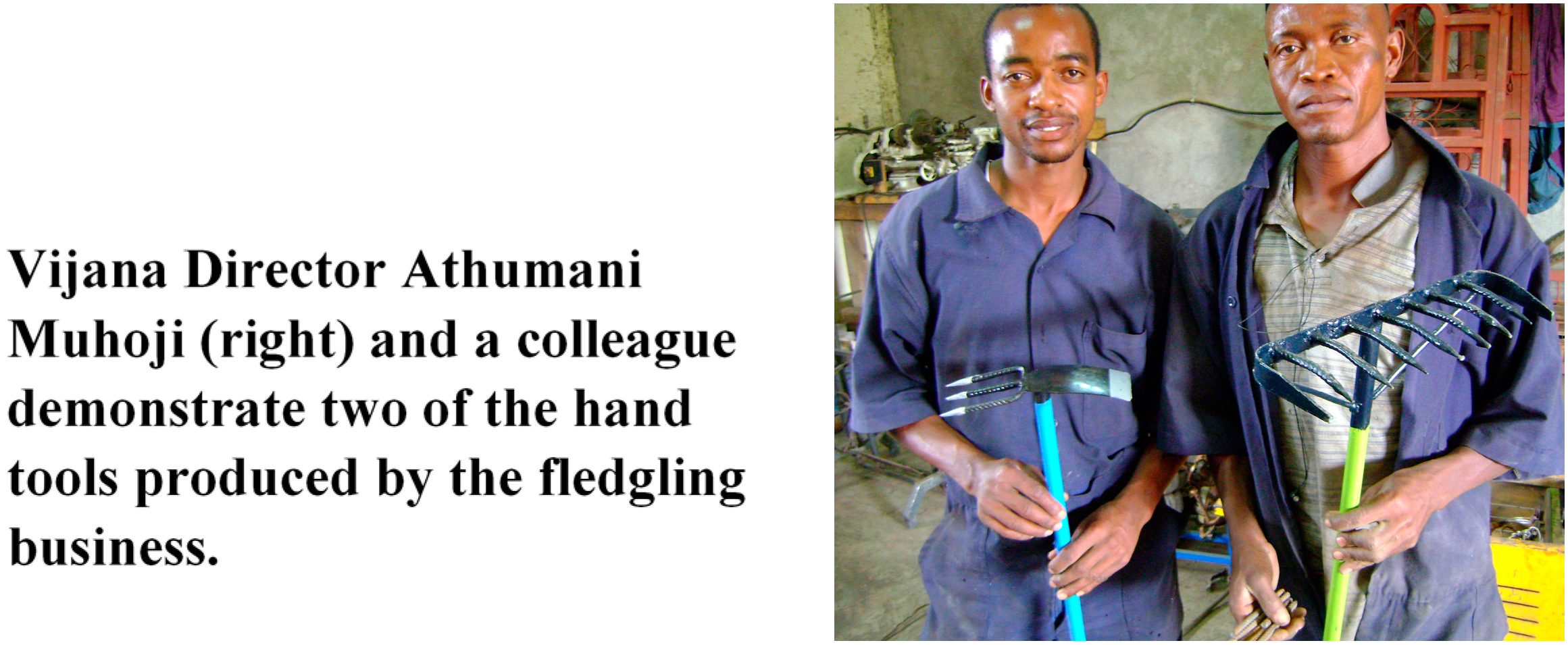

3. Local Manufacture

- Creation of a nurturing environment for the incubation of CA manufacturing capability. There are lessons to be learned in this regard from the Brazilian experience. From the 1980s the Brazilian government has been concerned to develop and disseminate CA equipment for smallholder farmers. This public sector support has been crucial to the success of CA for this farming sector. Appropriate machinery has been developed by consortia of private and public sector expertise and the farming community. Finance for machinery acquisition has been made available to smallholder farmers at very advantageous rates and this has stimulated the manufacturing industry to become self-sufficient. This is in stark contrast to the situation in many SSA countries where public sector investment in agricultural sector development is often very low compared to other developing regions of the world.

- Materials supply. Manufacturers in SSA frequently point out the uneven playing field on which they are expected to play and compete. There may be import duty on steel and machinery parts but not on imported tractors and agricultural machinery (e.g., in Kenya), which will disadvantage local manufacturers as it might be difficult for them to compete on price with their local products being made with materials subject to tax whilst imported agricultural equipment is tax free. Addressing this apparent injustice is one way that governments can work towards creating the necessary nurturing environment. Scrap steel may be appropriate for small-scale blacksmiths, but not larger scale manufacturers.

- A lack of appreciation of the importance of critical part design and materials considerations. Local manufacturers making an effort to break into the CA machinery market may often be at a disadvantage due to their limited knowledge of the details of design parameters for such machinery. Examples are: jab planter beaks; tine dimensions, attack angles, and materials (use of high carbon spring steel or easier to work alternatives such as Bennox steel); vertical loading on residue cutting discs; seed metering, placement, and covering; seed plates for different crops, fertilizer placement, depth control.

- Creation of demand. Manufacturers are reluctant to manufacture before having firm orders; at the same time farmers complain that CA technologies are not in the marketplace. This highlights the importance of development projects which, as happened in Brazil, can create the demand and maintain the interests of manufacturers until effective farmer demand can take over. Other actions have been seen to be important and these include the creation of dealer networks and their role in promotion through demonstrations and field days. The public sector’s role in providing subsidies and credit in the initial stages is also important. A specific targeted subsidy system (e.g., with vouchers—see Section 4) that supports the use of CA equipment would help. However, the public sector should not attempt short cuts by offering procurement programmes without a clear plan for equipment distribution and use including capacity building for users or service providers. Such entirely public sector driven tractor and equipment procurement programmes, and subsequent public sector driven mechanization hire stations, almost entirely failed and led to the closure of these schemes and a lack of interest in mechanization development programmes by donors, international financial institutions and the UN including FAO [27].

- Need for training to improve the skills base. Skills need to be improved at both the user and manufacturer levels in order for equipment to be effectively designed and properly operated and maintained. Important areas are calibration, field operation, maintenance, and business skills (especially for manufacturers and hire service providers). This theme is expanded and discussed in Section 4.

4. Service Provision

4.1. Technical Training

- Field operation of rippers, seeders and sprayers (Figure 17)

- Routine maintenance

- Servicing, e.g., of 2WT engines and transmissions

4.2. Management Training

- Feasibility studies

- ○

- Market research

- ○

- Partial budgets

- ○

- Supply chains

- ○

- Credit supply [31]

- Record keeping

- Accounting (balance sheets, profit and loss accounts, cash flow) [32]

- Costing of CA equipment use [33]

- Income assessment

- Business planning

- Marketing

- A tractor-drawn trailer for all year round transport services of all types of goods

- A tractor-powered maize sheller or harvester (Figure 18)

- A tractor-driven water pump for water lifting and irrigation

4.3. The Profitability of Service Provision

| Costs | USD |

|---|---|

| Annual Fixed Costs | |

| Depreciation (purchase price – residual value) ÷ useful life | 112.5 (a) |

| Interest (purchase price + residual value) ÷ 2 × i%) | 66.0 (b) |

| Sub-total (a + b) | 178.5 |

| Annual variable costs [34] | |

| Repairs and maintenance (130% of purchase price over useful life) | 162.5 (c) |

| Fuel (10% × engine hp = l/h) (l/h × annual use × diesel price = annual cost) | 500.0 (d) |

| Lubricants (1.5% × hourly fuel consumption) × annual use) | 7.5 (e) |

| Sub-total (c + d + e) | 670.0 |

| Total hourly costs | 1.7 |

| Costs | USD |

|---|---|

| Annual Fixed Costs | |

| Depreciation (purchase price – residual value) ÷ useful life | 292.5 (a) |

| Interest (purchase price + residual value) ÷ 2 × i%) | 171.6 (b) |

| Sub-total (a + b) | 464.1 |

| Annual variable costs [34] | |

| Repairs and maintenance (150% of purchase price over useful life) | 487.5 |

| Sub-total | 487.5 |

| Total hourly costs | 9.5 |

| Costs | USD |

|---|---|

| Annual Fixed Costs | |

| Depreciation (purchase price – residual value) ÷ useful life | 144.0 (a) |

| Interest (purchase price + residual value) ÷ 2 × i%) | 52.8 (b) |

| Sub-total (a + b) | 196.8 |

| Annual variable costs [34] | |

| Repairs and maintenance (250% of purchase price over useful life) | 400.0 |

| Sub-total | 596.8 |

| Total hourly costs | 2.0 |

| Costs of the investment | Benefits from the investment |

|---|---|

| Annual costs of: | Annual benefits: |

| 2WT | ‘x’ hours of no-till planting |

| No-till planter | ‘y’ tonnes of maize shelling |

| Maize sheller | ‘z’ tonne-kilometres of transport |

| trailer | etc. |

| Annual cost of labour hired for machinery operation | |

| TOTAL: A | TOTAL: B |

4.4. E-Vouchers

- Selection and verification of agro-dealers to be registered for the scheme. These will be dealers holding a certificate to indicate that the eligible products meet FAO’s technical standards.

- E-vouchers will carry the farmer’s name and ID number to ensure that only the intended beneficiaries are able to redeem inputs.

- The value of the voucher is not meant to pay the full cost of production of a crop or contractor service, but is a subsidy towards that cost. For LFs, the original vouchers were split into two, each valued at USD50 the first for seed and fertilizer, while the second was meant for the purchase of equipment such as chaka hoes, ox-drawn rippers (or parts for them) and knapsack sprayers. Beneficiary farmers were expected to top-up the voucher value with their own cash. The vouchers give farmers a choice in what they should buy and from whom. The voucher system provided a major boost for the business of agricultural input supply in Zambia.

- The electronic cards and associated mobile transaction system are procured from a technical provider, Mobile Transactions Zambia Limited (MTZL), which at the beginning was the only supplier of such services in Zambia. Now several companies provide similar services. The responsibilities of the technical service provider are to design the electronic card, to oversee the printing of the card and to provide software and suitably modified mobile phones for use as point-of-sale devices at agro-dealers’ outlets. MTZL also provided training for Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock (MAL) extension staff and the staff of agro-dealers. The cost of training of agro-dealers was charged at USD100 for each attendee in 2012. MTZL staff were always available to deal with any technical problems that arose during the operation of the e-voucher exchange.

- Selection of the implementing partner. This will normally be the Ministry of Agriculture (MAL in the case of Zambia).

- Selection of beneficiaries will be according to agreed criteria and priorities. In the case of Zambia LFs are selected by MAL field staff and they are responsible for disseminating CA technology in their camps.

- The distribution of the cards to the identified beneficiaries is the responsibility of MAL via its field extension staff network. Cards are issued against a signature to ensure that beneficiaries are bona fide.

- Redemption of the cards is accompanied by the recipient’s ID card number to ensure that only the designated beneficiary can use the voucher.

- Payment for inputs is instantaneous through the use of the point-of-sale electronic card readers. FAO needed to open and fund a bank account for this purpose.

5. Conclusions

- Sustainable intensification. The smallholder farming sector is key to producing the food requirements of an increasing, and increasingly urban, population. Increased production must be accompanied by natural resource conservation if mankind is to have a future on this planet. SCPI will include CA as a standard practice and CA requires specific mechanization inputs. Smallholder farmers are not often in a position to invest in expensive farm machinery and the best vehicle to provide them with the required services is via well trained and well equipped private sector entrepreneurial CA service providers.

- Local manufacture. Local manufacture of CA equipment is a desirable goal as it not only helps to stimulate the local economy, but also provides the opportunity to adapt technologies to local conditions be they crops, soils, climate, production systems, technical knowledge, manufacturing skills or material supply, amongst other factors.

- Policy guidelines. Governments will often need guidance on how to provide the best environment for nurturing a local CA equipment manufacturing industry. Financial support to the smallholder farming sector to assist farmers in the purchase of CA equipment will directly stimulate the local supply chain. The correction of anomalies affecting local manufacture, such as the existence of import duty on machine components and raw materials, but not on imported agricultural machinery, will need to be removed to provide an equitable environment for local industry. Training of CA equipment design and manufacturing techniques may be required (e.g., SIDO in Tanzania).

- Demand creation. Efforts at creating demand for CA should be on-going. Although the public sector has a major role to play (for example in organizing field days and improving extension efforts), the private sector should also be encouraged through demonstration plots, out-grower technical support, machinery fairs and the formation and consolidation of CA farmer mutual support groups.

- Service provision. Given the problems of affordability and availability of CA equipment, including power sources, a promising solution is to equip and train entrepreneurial CA service providers. Equipment can be centrally procured and delivered on credit to would-be service providers. Loan payments are repaid from the resulting business activity. E-voucher systems can be employed to stimulate initial demand for the services but they should be withdrawn as soon as demand is sufficiently high.

- Training. Service providers not only need good CA equipment, but will also often need training in the technical aspects of its correct use, calibration and maintenance, as well as training on the managerial skills of identifying and running a successful service provision model.

Acknowledgements

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture. Innovation in Family Farming; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2014; p. 139. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Cash Transfers: Promoting Sustainable Livelihoods in Sub Saharan Africa. Available online: http://www.fao.org/resources/infographics/infographics-details/en/c/178851/ (accessed on 16 February 2015).

- Ngwira, A.R.; Thierfelder, C.; Lambert, D.M. Conservation agriculture systems for Malawian smallholder farmers: Long-term effects on crop productivity, profitability and soil quality. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2013, 28, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Save and Grow. A Policymaker’s Guide to the Sustainable Intensification of Smallholder Crop Production; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2011; p. 102. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Mechanization for Rural Development. A Review of Patterns and Progress from around the World; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2013; p. 336. [Google Scholar]

- Kienzle, J.; Sims, B.G. Agricultural mechanization strategies for sustainable production intensification: Concepts and cases from (and for) sub-Saharan Africa. 2014. Available online: http://www.clubofbologna.org/ew/documents/3_1b_KNR_Kienzle_mf.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2015).

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Fifth Assessment Report (AR5). 2014. Available online: www.ipcc.ch (accessed on 22 April 2015).

- Lal, R. Managing soil carbon through sustainable intensification of agro-ecosystems. Agric. Dev. 2015, 24, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- FAO Conservation Agriculture website. Available online: www.fao.org/ag/ca/ (accessed on 22 April 2015).

- Baker, J.C. Seeding openers and slot shape. In No Tillage Seeding in Conservation Agriculture, 2nd ed.; Baker, C.J., Saxton, K.E., Eds.; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and CAB International: Rome, Italy and Wallingford, UK, 2007; pp. 34–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, F.; Justice, S.E.; Hobbs, P.R.; Baker, J.C. No-tillage drill and planter design—Small-scale machines. In No Tillage Seeding in Conservation Agriculture, 2nd ed.; Baker, C.J., Saxton, K.E., Eds.; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and CAB International: Rome, Italy and Wallingford, UK, 2007; pp. 204–225. [Google Scholar]

- Sims, B.G. Labour saving technologies for smallholder farmers; An initiative of the Gates Foundation. Agric. Dev. 2014, 21, 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Jat, M.L.; Kapil; Kamboj, B.R.; Sidhu, H.S.; Singh, M.; Bana, A.; Bishnoi, D.; Gathala, M.; Saharawat, Y.S.; Kumar, V.; et al. Operational Manual for Turbo. Happy Seeder—Technology for Managing Crop Residues with Environmental Stewardship; International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR): New Delhi, India, 2013; p. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Baudron, F.; Blackwell, J.; Sims, B.; Justice, S.; Kahan, D.G.; Rose, R.; Mkomwa, S.; Kaumbutho, P.; Sariah, J.; Mogesi, G.; et al. Re-examining appropriate mechanization in Africa: Two-wheel tractors, conservation agriculture, and private sector involvement. Food Secur. Sci. Sociol. Econ. Food Prod. Access Food 2015, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell, J.; Charles Sturt University, Wagga Wagga, New South Wales, Australia. Personal communication, 2015.

- Conservation Farming Unit (CFU). Conservation Farming Handbook for Ox Farmers in Agro-Ecological Regions I & II; Conservation Farming Unit, National Farmers’ Union, FAO: Lusaka, Zambia, 2006; p. 47. [Google Scholar]

- Casão Junior, R.; de Araújo, A.G.; Fuentes Llanillo, R. No-Till Agriculture in Southern Brazil; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and Agricultural Research Institute of Paraná State (IAPAR): Rome, Italy and Londrina, Brazil, 2012; p. 61. [Google Scholar]

- Sims, B.G.; Thierfelder, C.; Kienzle, J.; Friedrich, T.; Kassam, A. Development of the conservation agriculture equipment industry in sub-Saharan Africa. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2012, 28, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassam, A.; Friedrich, T.; Derpsch, R.; Kienzle, J. Worldwide adoption of Conservation Agriculture. In Proceedings of 6th World Congress on Conservation Agriculture, Winnipeg, Canada, 22–25 June 2014.

- FAO. Hire Services by Farmers for Farmers; FAO Diversification Booklet 19; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2011; p. 83. [Google Scholar]

- FAO Regional Office for Africa. Zambia, EU and FAO Launch Conservation Agriculture Project. Available online: http://www.fao.org/africa/news/detail-news/en/c/215584/ (accessed on 28 March 2015).

- Sustainable Agricultural Information Initiative (SUSTAINET EA). Technical Manual. Farmer Field School Approach; Sustainable Agriculture Information Initiative: Nairobi, Kenya, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chabata, I.; de Wolf, J. The Lead Farmer Approach: An Effective Way of Agricultural Technology Dissemination? Available online: http://www.n2africa.org/sites/n2africa.org/files/images/N2Africa%20Poster%20Isaac%20.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2015).

- Harald, M.; Head of Programme WFP, Zambia. Personal communication, 2015.

- Rusiga, A.; P4P Support Officer, WFP, Zambia. Personal communication, 2015.

- Kienzle, J.; Hollinger, F. Back to Office Report from Tanzania Mission; Rural Infrastructure and Agro-Industries Division and Investment Center Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Investment in Agricultural Mechanization in Africa, Conclusions and Recommendations from a Round Table Meeting of Experts; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2011; p. 76. [Google Scholar]

- Small Industries Development Organization (SIDO), Tanzania. Available online: www.sido.go.tz (accessed on 22 April 2015).

- Selam Awassa Business Group. Available online: www.selamawassa.org (accessed on 22 April 2015).

- FAO. Testing and Evaluation of Agricultural Machinery and Equipment: Principles and Practices; FAO Agricultural Services Bulletin 110; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1994; p. 102. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Explaining How to Use Financial Services; Talking About Money 6; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2011; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Explaining Cash Flow and Savings; Talking About Money 1; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome Italy, 2005; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Explaining the Finances of Machinery Ownership; Talking About Money 3; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2009; p. 38. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Agricultural Engineering in Development: Selection of Mechanization Inputs; Agricultural Services Bulletin 84; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1990; p. 105. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. E-Vouchers in Zimbabwe: Guidelines for Agricultural Input Distribution; Emergency, Rehabilitation and Coordination Unit (Zimbabwe), Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sims, B.; Kienzle, J. Mechanization of Conservation Agriculture for Smallholders: Issues and Options for Sustainable Intensification. Environments 2015, 2, 139-166. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments2020139

Sims B, Kienzle J. Mechanization of Conservation Agriculture for Smallholders: Issues and Options for Sustainable Intensification. Environments. 2015; 2(2):139-166. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments2020139

Chicago/Turabian StyleSims, Brian, and Josef Kienzle. 2015. "Mechanization of Conservation Agriculture for Smallholders: Issues and Options for Sustainable Intensification" Environments 2, no. 2: 139-166. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments2020139

APA StyleSims, B., & Kienzle, J. (2015). Mechanization of Conservation Agriculture for Smallholders: Issues and Options for Sustainable Intensification. Environments, 2(2), 139-166. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments2020139