Plant Accumulation of Metals from Soils Impacted by the JSC Qarmet Industrial Activities, Central Kazakhstan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Soil Sampling, Processing, and Basic Characteristics

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Cultural Practices

2.4. Plant Biomass Measurement and Processing

2.5. Total Metal Concentrations in Shoot Biomass

2.6. Total Metal Concentrations in Soil

2.7. Analysis of Soil Baseline Properties

2.8. Quality Assurance/Quality Control

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Initial Metal Concentrations in Soil

3.2. Plant Biomass Production

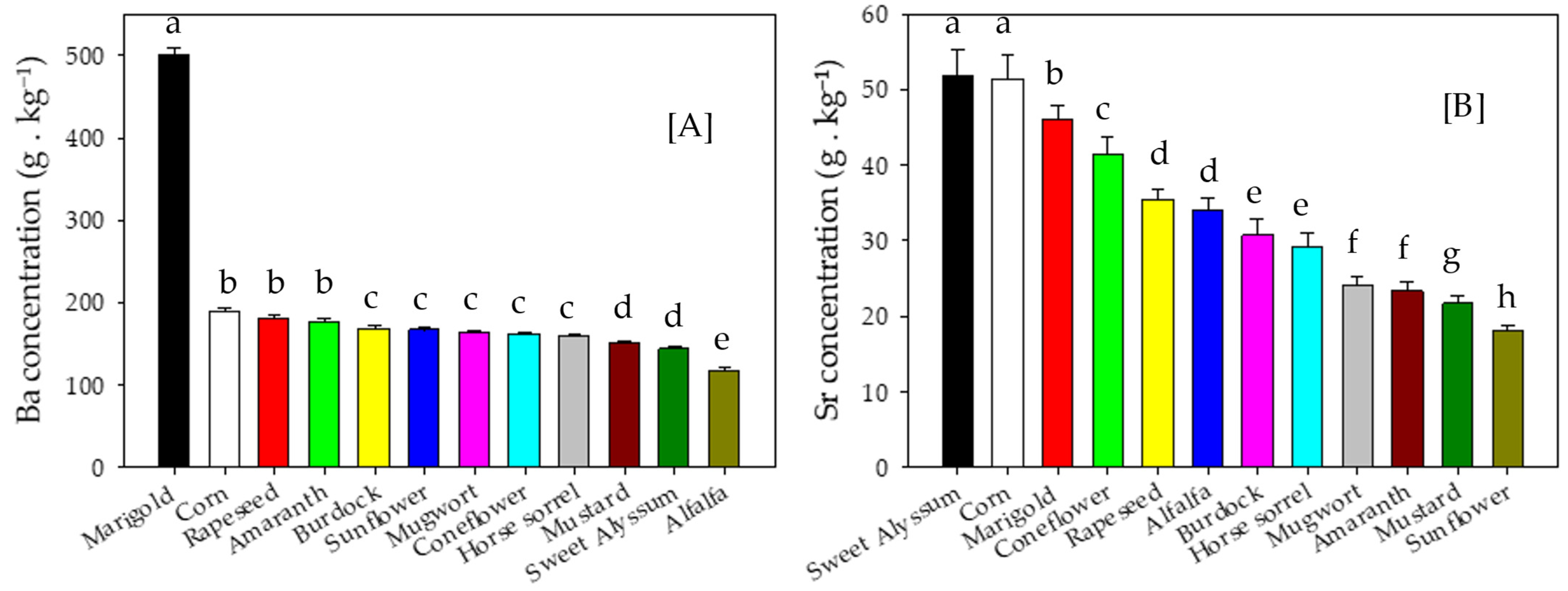

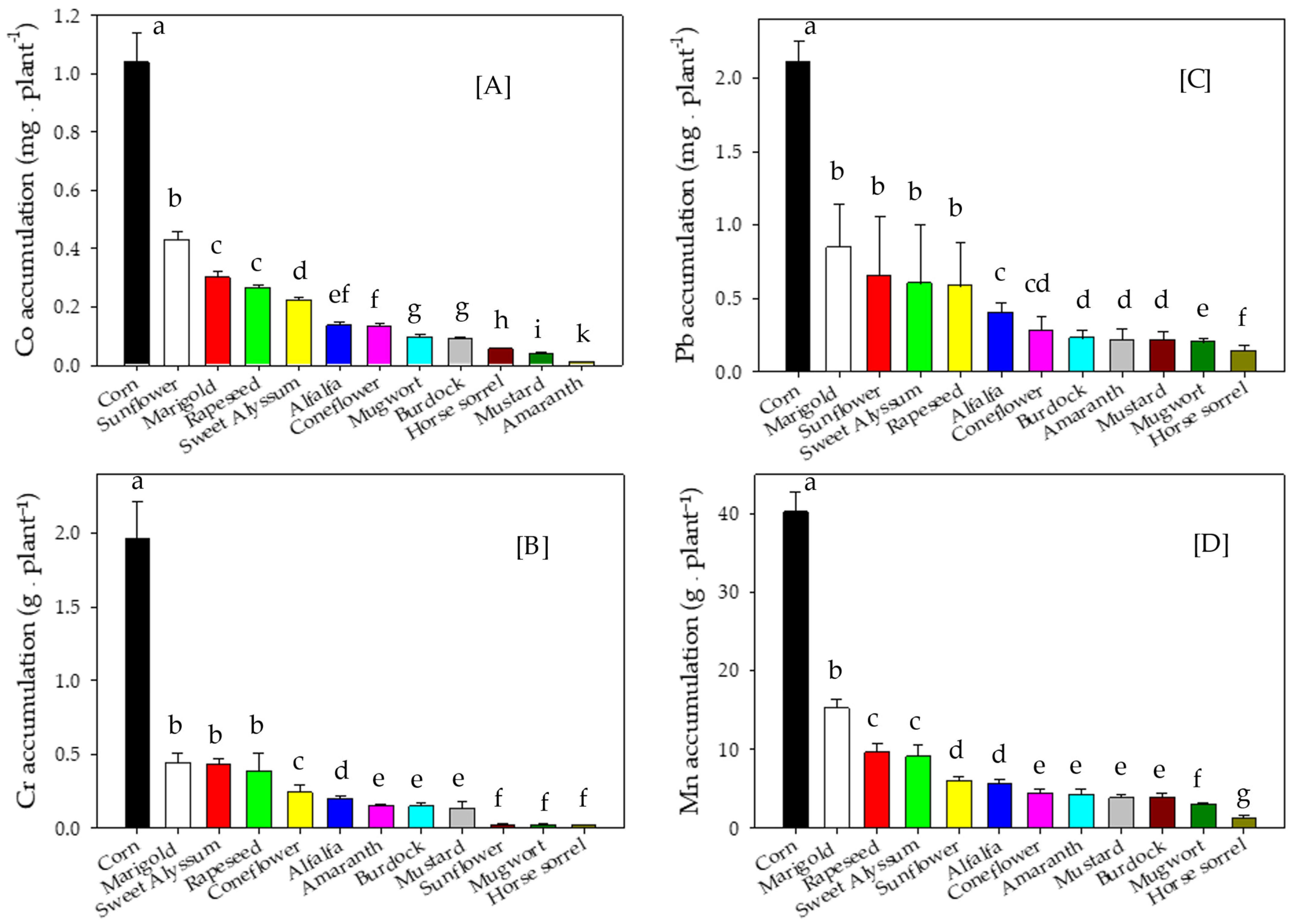

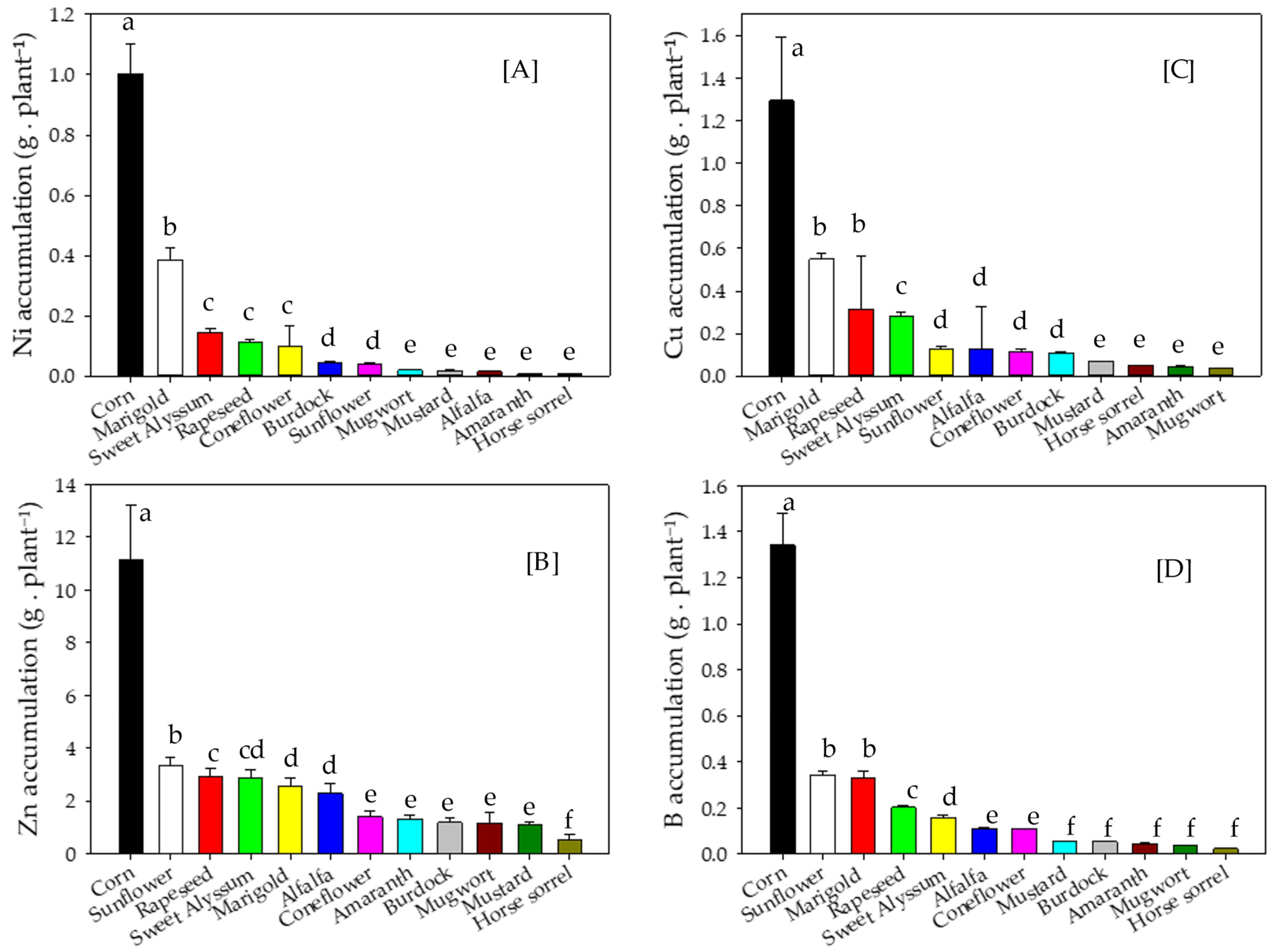

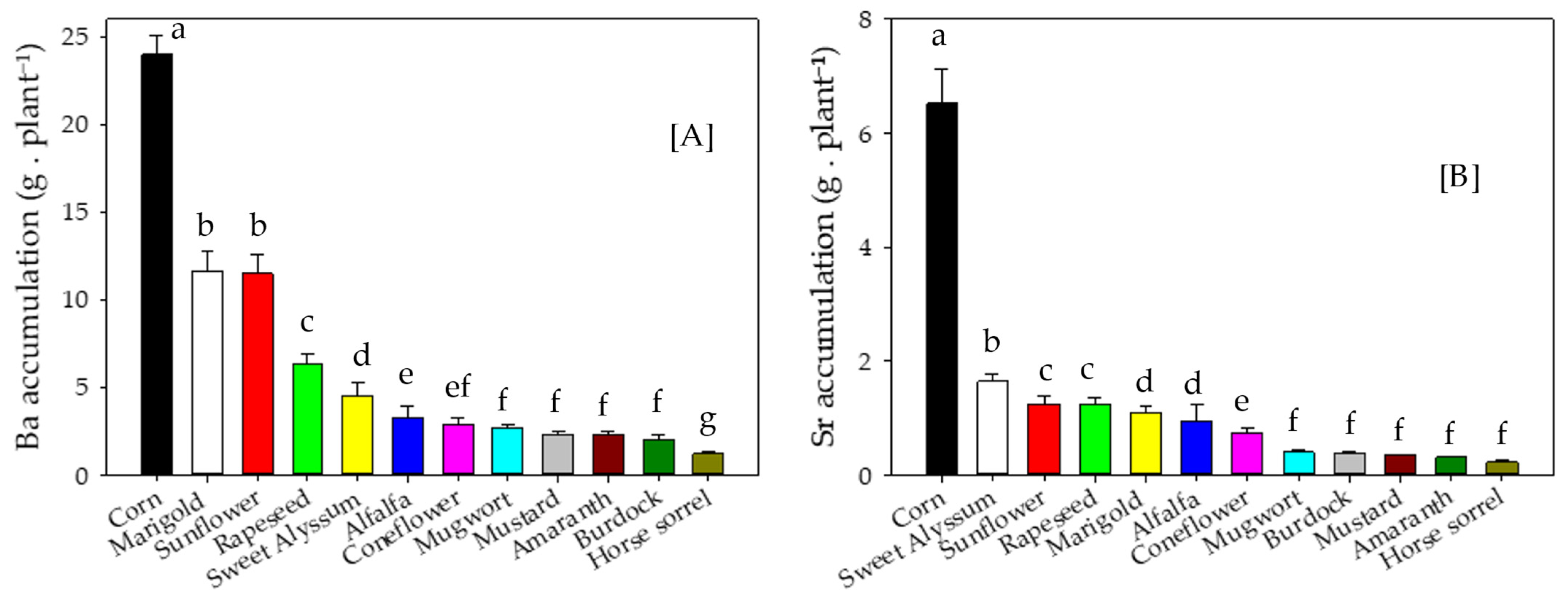

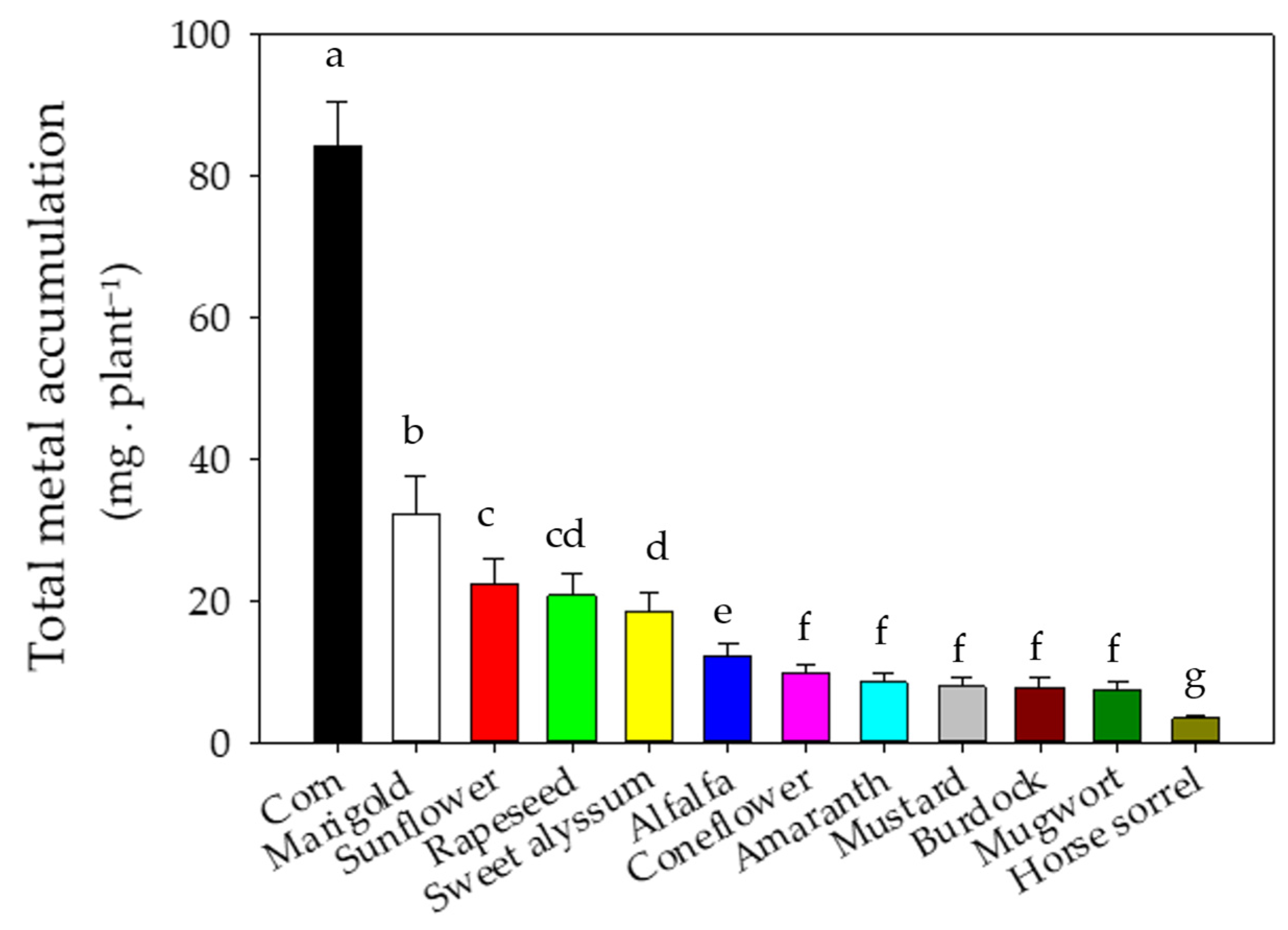

3.3. Metal Concentrations and Accumulation in Shoot Biomass

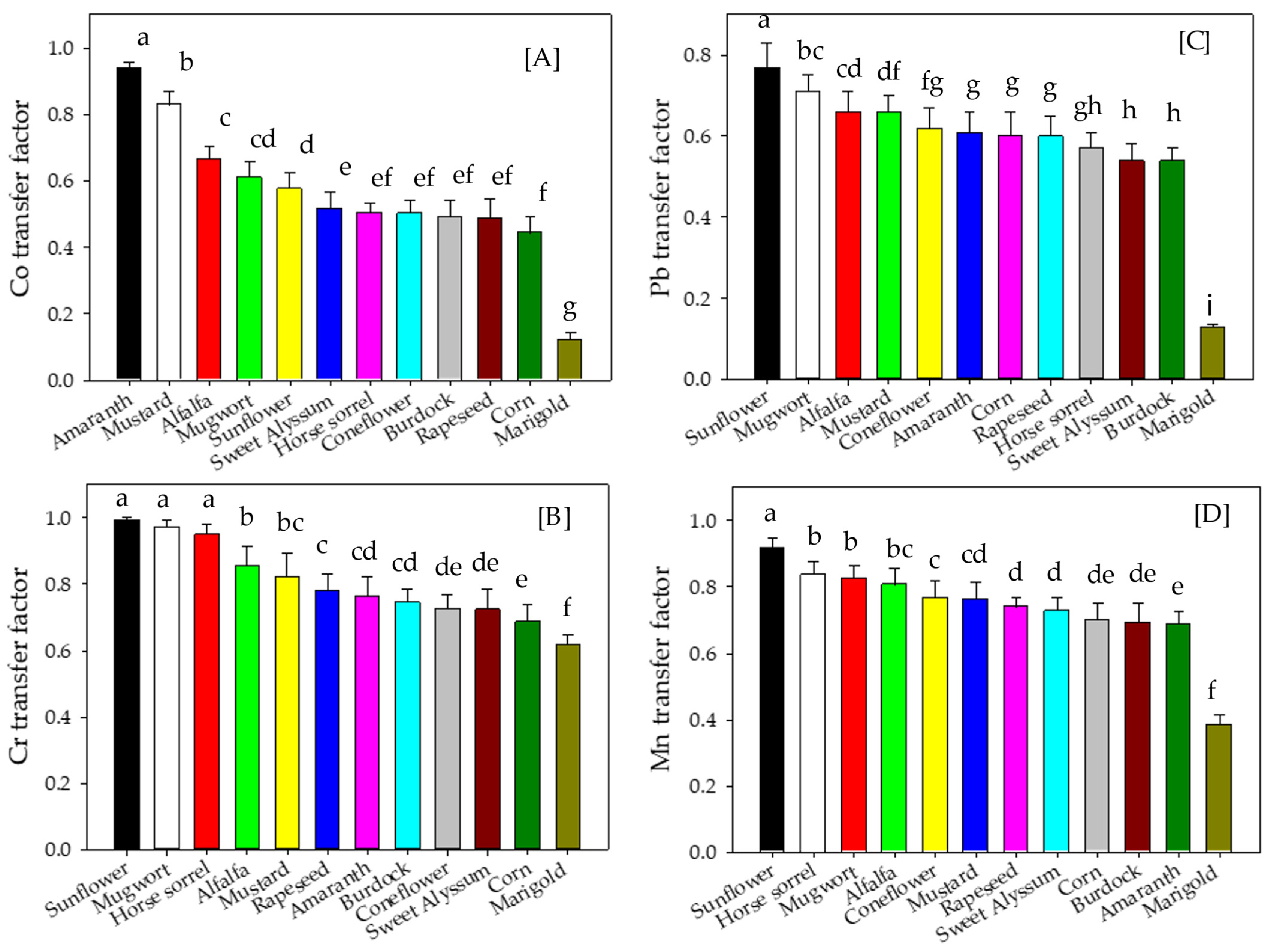

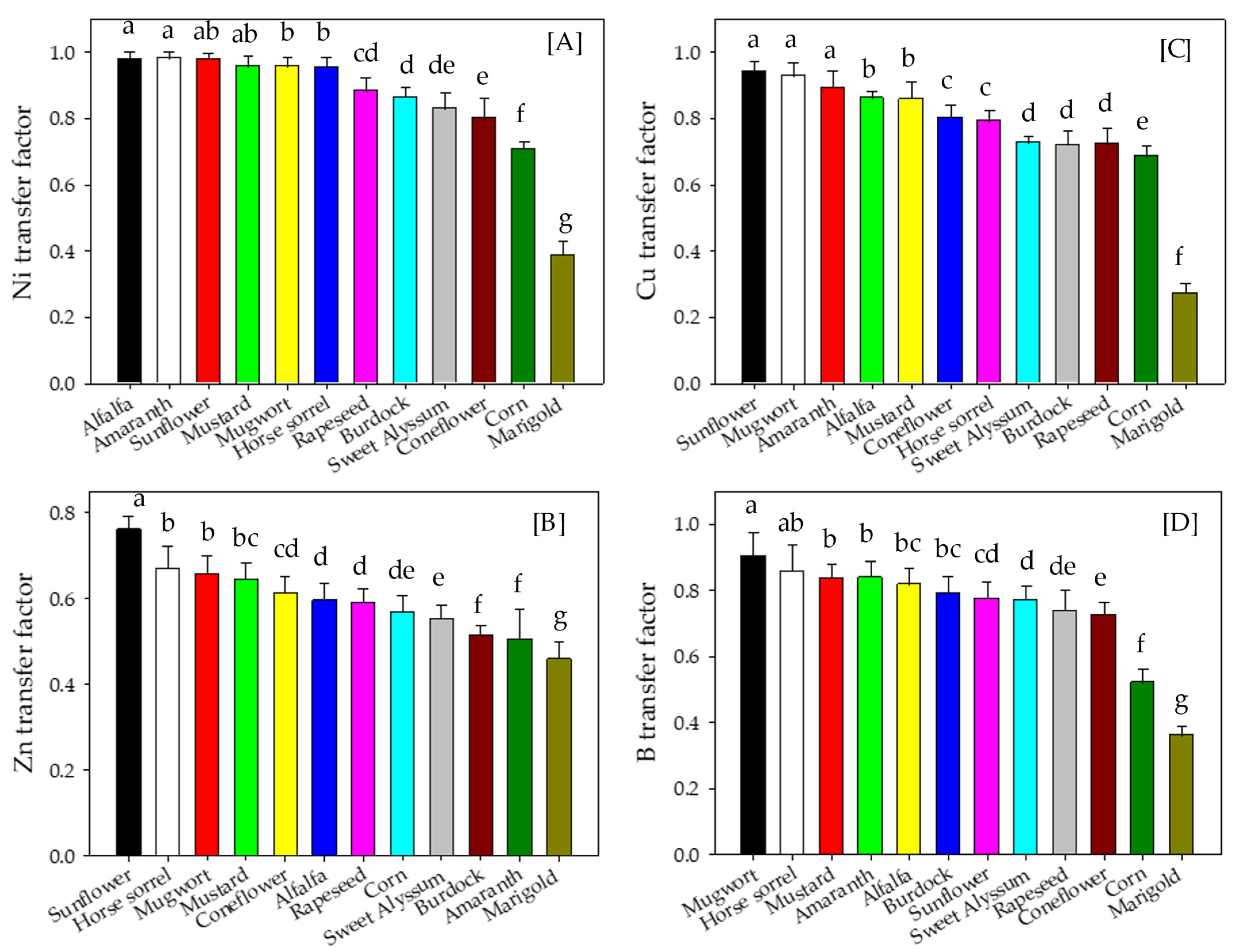

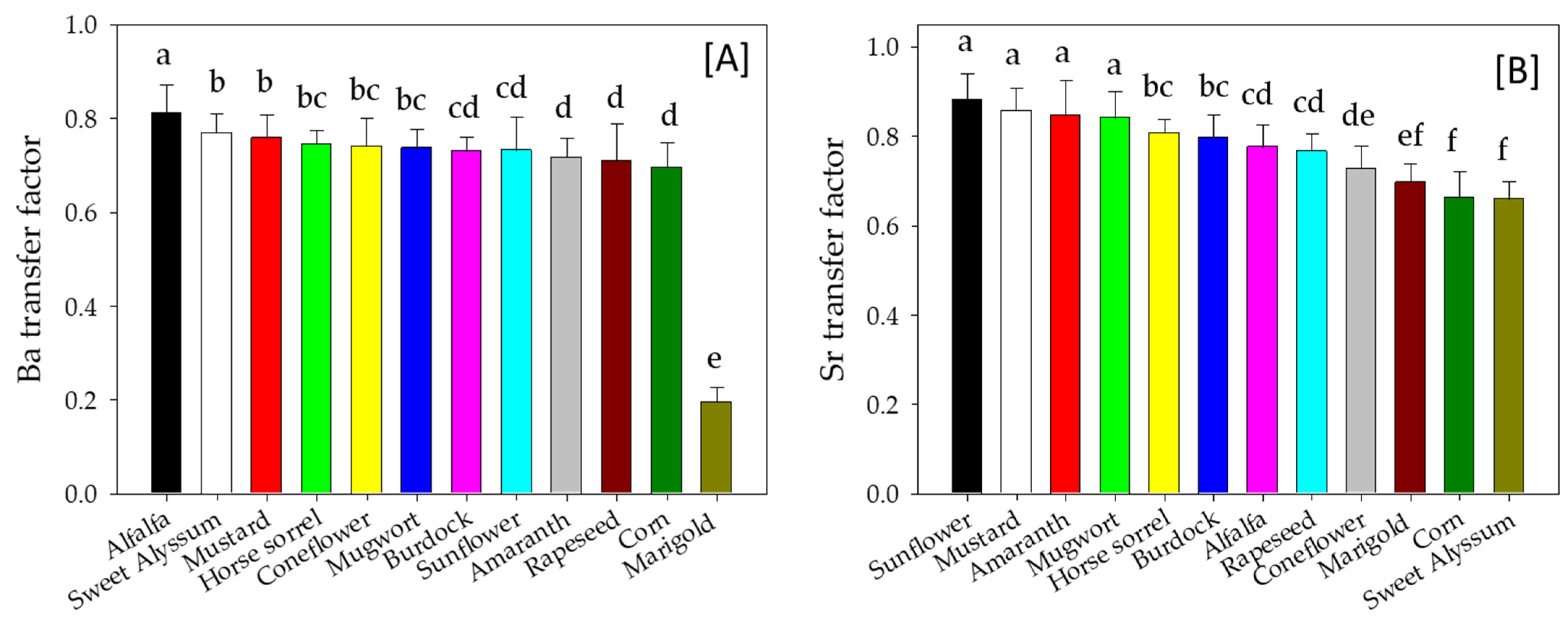

3.4. Metal Transfer Factor of Plants

4. Discussion

4.1. Metal Concentrations in Soil

4.2. Plant Biomass Production

4.3. Metal Concentrations and Accumulation in Shoot Biomass

4.4. Metal Transfer Factor of Plants

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ondrasek, G.; Shepherd, J.; Rathod, S.; Dharavath, R.; Rashid, M.I.; Brtnicky, M.; Shahid, M.S.; Horvatinec, J.; Rengel, Z. Metal contamination—A global environmental issue: Sources, implications & advances in mitigation. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 3904–3927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, B.; Linsheng, Y. A review of heavy metal contaminations in urban soils, urban road dusts and agricultural soils from China. Microchem. J. 2010, 94, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woszczyk, M.; Spychalski, W.; Boluspaeva, L. Trace metal (Cd, Cu, Pb, Zn) fractionation in urban-industrial soils of Ust-Kamenogorsk (Oskemen), Kazakhstan—Implications for the assessment of environmental quality. Environ. Monit. Assess 2018, 190, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minkina, T.; Mandzhieva, S.; Motusova, G.; Burachevskaya, M.; Nazarenko, O.; Sushkova, S.; Kızılkaya, R. Heavy metal compounds in a soil of technogenic zone as indicate of its ecological state. Eurasian J. Soil Sci. 2014, 3, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doabi, S.A.; Karami, M.; Afyuni, M.; Yeganeh, M. Pollution and health risk assessment of heavy metals in agricultural soil, atmospheric dust, and major food crops in Kermanshah province, Iran. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 163, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramazanova, E.; Bulgakova, G.; Lee, W.; Tsatsakis, A.; Koptyug, A. Stochastic risk assessment of urban soils contaminated by heavy metals in Kazakhstan. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 750, 141535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, H.F.; Silva, N.F.; Oliveira, C.M.; Matos, M.J. Heavy Metals contamination of urban soils—A decade study in the city of Lisbon, Portugal. Soil Syst. 2021, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhakypbek, Y.; Rysbekov, K.; Lozynskyi, V.; Mikhalovsky, S.; Salmurzauly, R.; Begimzhanova, Y.; Kezembayeva, G.; Yelikbayev, B.; Sankabayeva, A. Geospatial and correlation analysis of heavy metal distribution on the territory of integrated steel and mining company Qarmet JSC. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrekidan, A.; Weldegebriel, Y.; Hadera, A.; Van der Bruggen, B. Toxicological as-sessment of heavy metals accumulated in vegetables and fruits grown in Ginfel river near Sheba Tannery, Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2013, 95, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoakwah, E.; Ahsan, S.; Rahman, M.A.; Asamoah, E.; Essumang, D.K.; Ali, M.; Islam, K.R. Artisanal gold mining impacts on heavy metals pollution of soil-water-vegetative ecosystems. J. Soil Sed. 2020, 29, 788–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Sun, G.X.; Ren, Y.; Luo, X.S.; Zhu, Y.G. Urban soil, and human health: A review. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2018, 69, 196–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diacono, E.; Faye, B.; Meldebekova, A.; Konuspayeva, G. Plant, water, and milk pollution in Kazakhstan. In Impact of Pollution on Animal Products; Sinyavskiy, Y., Faye, B., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 107–116. [Google Scholar]

- Kaliaskarova, Z.; Aliyeva, Z.; Ikanova, A.; Negim, E. Soil pollution with heavy metals on the land of the Karasai landfill of municipal solid waste in Almaty city. News Acad. Sci. Repub. Kaz. Ser. Geol. Tech. Sci. 2019, 6, 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baubekova, A.; Akindykova, A.; Mamirova, A.; Dumat, C.; Jurjanz, S. Evaluation of environmental contamination by toxic trace elements in Kazakhstan based on reviews of available scientific data. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 43315–43328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toishimanov, M.; Abilda, Z.; Daurov, D.; Daurova, A.; Zhapar, K.; Sapakhova, Z.; Kanat, R.; Stamgaliyeva, Z.; Zhambakin, K.; Shamekova, M. Phytoremediation properties of sweet potato for soils contaminated by heavy metals in South Kazakhstan. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iztileu, A.; Grebeneva, O.; Otarbayeva, M.; Zhanbasinova, N.; Ivashina, E.; Dui-senbekov, B. Intensity of soil contamination in industrial centers of Kazakhstan. CBU Int. Conf. Proc. 2013, 1, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiman, N.; Gulnaz, S.; Alena, M. The characteristics of pollution in the big industrial cities of Kazakhstan by the example of Almaty. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2018, 16, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzychenko, I.; Jamalova, G.; Mussina, U.; Kazulis, V.; Blumberga, D. Case study of lead pollution in the roads of Almaty. Energy Procedia 2017, 113, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naimanova, A.; Akhmetova, S.; Issayeva, A.; Vyrakhmanova, A.; Alipbekova, A. Phytoaccumulation of heavy metals in South Kazakhstan Soils (Almaty and Turkestan Regions): An evaluation of plant-based remediation potential. Int. J. Des. Nat. Ecodyn. 2024, 19, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghighizadeh, A.; Omid, R.; Arman, N.; Zahra, H.; Mina, H.; Soheila, H.; Soheila, D.A.; Ali, A.B. Comprehensive analysis of heavy metal soil contamination in mining environments: Impacts, monitoring techniques, and remediation strategies. Arab. J. Chem. 2024, 17, 105777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozma, P.; Mihaela, R.; Mariana, M.; Maria, G. Phytoremediation: A sustainable and promising biobased approach to heavy metal pollution management. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 1001, 180458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Ent, A.; Baker, A.J.M.; Reeves, R.D.; Pollard, A.J.; Schat, H. Hyperaccumulators of metal and metalloid trace elements: Facts and fiction. Plant Soil 2013, 362, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, R.D.; Baker, A.J.M.; Jaffré, T.; Erskine, P.D.; Echevarria, G.; van der Ent, A. A global database for plants that hyperaccumulate metal and metalloid trace elements. New Phytol. 2017, 218, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manara, A.; Elisa, F.; Antonella, F.; Giovanni, D. Evolution of the metal hyperaccumulation and hyper-tolerance traits. Plant Cell Environ. 2020, 43, 2969–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Ent, A.; Rylott, E.L. Inventing hyperaccumulator plants: Improving practice in phytoextraction research and terminology. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2024, 26, 1379–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoikou, V.; Andrianos, V.; Stasinos, S.; Kostakis, M.G.; Attiti, S.; Thomaidis, N.S.; Zabetakis, I. Μetal uptake by sunflower (Helianthus annuus) irrigated with water polluted with chromium and nickel. Foods 2017, 6, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedi, T.; Gavanji, S.; Mojiri, A. Lead and Zinc uptake and toxicity in maize and their management. Plants 2022, 11, 1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, S.; Mrmošanin, J.; Arsić, B.; Pavlović, A.; Tošić, S. Uptake of some heavy metal(oid)s by sunflower. Chem. Naissensis 2023, 5, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelikbayev, B.; Imanbek, F.; Jamalova, G.; Kalogerakis, N.; Islam, K. Phytoremediation of contaminated urban soils spiked with heavy metals. Eurasian J. Soil. Sci. 2024, 13, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storozhenko, D.M. Soils of the Kazakh SSR. Issue 8. Karaganda Region; Publisher Nauka (Science): Alma-Ata, Kazakhstan, 1967; 331p. (In Russian)

- US-EPA Method 3051A. Microwave Assisted with Acid Digestion of Sediments, Sludges, Soils, and Oils. Revision 1. 2007. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-12/documents/3051a.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2007).

- Prabasiwi, D.S.; Murniasih, S.S.; Rozana, K. Transfer factor as indicator of heavy metal content in plants around adipala steam power plant. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1436, 012133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, Z.U.; Khan, S.; Shah, M.T.; Brusseau, M.I.; Khan, S.A.; Mainhagu, J. Transfer of heavy metals from soils to vegetables and associated human health risks at selected sites in Pakistan. Pedosphere 2018, 28, 666–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GOST 26423-85; Soils—Methods for Determination of Specific Electric Conductivity, pH, and Solid Residue of Water Extract. 2024. USSR State Standards Committee, USSR Ministry of Agriculture: Moscow, Russia, 1985. Available online: https://www.russiangost.com/p-16105-gost-26423-85.aspx (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Jankauskas, B.; Jankauskiene, G.; Slepetiene, A.; Fullen, M.A.; Booth, C.A. International comparison of analytical methods of determining the soil organic matter content of Lithuanian Eutric albeluvisols. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2006, 37, 707–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GOST 27821-88; Soils. Determination of Base Absorption Sum by Kappen Method. 1988. Available online: https://www.russiangost.com/p-49750-gost-27821-88.aspx (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- GOST 12536-2014; Soils—Methods of Laboratory Granulometric (Grain-Size) and Microaggregate Distribution. USSR State Standards Committee, USSR Ministry of Agriculture: Moscow, Russia, 2014. Available online: www.russiangost.com/p-138335-gost-12536-2014.aspx (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- FAO; WHO. ALINORM 01/12A; Food Additives and Contaminants—Joint Codex Alimentarius Commission, FAO/WHO Food Standards Program. FAO: Rome, Italy; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; p. 1289.

- CX/CF 21/14/13; Discussion Paper on Cadmium and Lead in Quinoa—Joint FAO/WHO Food Standard Programme Codex Committee on Contaminants in Foods, 14th Session, 3–7 and 13 May 2021, Agenda Item 15. FAO: Rome, Italy; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/sh-proxy/en/?lnk=1&url=https%253A%252F%252Fworkspace.fao.org%252Fsites%252Fcodex%252FMeetings%252FCX-735-14%252FWDs-2021%252Fcf14_13e.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Koshim, A.; Karatayev, M.; Clarke, M.L. Industrial pollution, and environmental degradation in Central Kazakhstan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 12345–12358. [Google Scholar]

- Beisenova, R.; Issanova, G.; Abuduwaili, J. Heavy metal pollution in industrial cities of Kazakhstan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5678. [Google Scholar]

- Alloway, B.J. Heavy Metals in Soils: Trace Metals and Metalloids in Soils and Their Bioavailability, 4th ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kabata-Pendias, A. Trace Elements in Soils and Plants, 5th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Querol, X.; Alastuey, A.; Moreno, N. Environmental impact of coal combustion residues. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2008, 75, 77–96. [Google Scholar]

- Csavina, J.; Field, J.; Taylor, M.P. Metal contamination from smelters. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 424, 38–54. [Google Scholar]

- Mielke, H.W.; Reagan, P.L. Soil is an important pathway of human lead exposure. Environ. Health Perspect. 1998, 106, 217–229. [Google Scholar]

- Issanova, G.; Jilili, R.; Abuduwaili, J. Legacy pollution in post-Soviet industrial regions. Environments 2019, 6, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Rizwan, M.; Ali, S.; Rehman, M.Z.U.; Malik, S.; Adrees, M.; Qayyum, M.F. Effect of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles on growth and physiology of plants: A critical review. Chemosphere 2020, 260, 127521. [Google Scholar]

- Atta, M.I.; Zehra, S.S.; Ali, H.; Ali, B.; Abbas, S.N.; Aimen, S.; Sarwar, S.; Ahmad, I.; Hussain, M.; Al-Ashkar, I.; et al. Assessing the effect of heavy metals on maize (Zea mays L.) growth and soil characteristics: Plants-implications for phytoremediation. PeerJ. 2023, 11, e16067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samal, S.K.; Datta, S.P.; Dwivedi, B.S.; Meena, M.C.; Nogiya, M.; Choudhary, M.; Golui, D.; Raza, M.B. Phytoextraction of nickel, lead, and chromium from contaminated soil using sunflower, marigold, and spinach: Comparison of efficiency and fractionation study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 50847–50863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelova, V.; Ivanova, R.; Todorov, G.; Ivanov, K. Potential of sunflower for phytoremediation of contaminated soils. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2010, 12, 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Elik, Ü.; Gül, Z. Accumulation potential of lead and cadmium metals in maize (Zea mays L.) and effects on physiological-morphological characteristics. Life 2025, 15, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, P.; Ye, Z.H.; Lan, C.Y.; Xie, Z.W.; Shu, W.S. Chemically assisted phyto-extraction of heavy metal contaminated soils using three plant species. Plant Soil 2005, 276, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Waraich, E.A.; Nawaz, F.; Ashraf, M.Y.; Khalid, M. Performance of maize cultivars under cadmium stress. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2015, 17, 133–140. [Google Scholar]

- Tóth, G.; Hermann, T.; Da Silva, M.R.; Montanarella, L. Heavy metals in agricultural soils of the European Union with implications for food safety. Environ. Int. 2016, 88, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnár, E.; Bobek-Nagy, J.; Juzsakova, T.; Kurdi, R.; Rauch, R. Tagetes erecta as a nickel phytore-mediator: Insights into accumulation and growth response. Circ. Econ. Sust. 2025, 5, 6483–6498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, S.; Pandey, V.C. Phytoremediation potential of ornamental plants grown in multi-metal contaminated soils. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 41875–41890. [Google Scholar]

- Ghori, N.H.; Ghori, T.; Hayat, M.Q.; Imadi, S.R.; Gul, A.; Altay, V.; Ozturk, M. Heavy metal stress and responses in plants. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 16, 1807–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuypers, A.; Plusquin, M.; Remans, T.; Jozefczak, M.; Keunen, E.; Gielen, H.; Vangronsveld, J. Cadmium stress: An oxidative challenge. Biometals 2010, 23, 927–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheetal, K.R.; Singh, S.D.; Anand, A.; Prasad, S. Heavy metal accumulation and effects on growth, biomass and physiological processes in mustard. Indian J. Plant Physiol. 2016, 21, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tőzsér, D.; Yelamanova, A.; Sipos, B.; Magura, T.; Simon, E. A meta-analysis on the heavy metal uptake in Amaranthus species. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 85102–85112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, A.J.M.; Whiting, S.N. In search of the Holy Grail—A further step in understanding metal hyperaccumulation? New Phytol. 2002, 155, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, P.; Guo, Z.; Xiao, X.; Peng, C. Uptake, translocation, and accumulation of heavy metals by Tagetes species in contaminated soils. Int. J. Phytoremed. 2023, 25, 1035–1046. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yeh, K.-C. Rhizosphere processes and metal uptake in plants exposed to mixed-metal contamination. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 268, 115860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, Q.; Wei, S. Organic acid-mediated chelation and translocation of heavy metals in plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 185, 152–161. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Huang, G.; An, C.; Xin, X. Biomass-driven phytoextraction efficiency of maize in industrially contaminated soils. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 336, 122523. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Sharma, R.K.; Agrawal, M.; Marshall, F. Sunflower as a potential candidate for metal uptake under environmental stress conditions. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 287. [Google Scholar]

- van der Ent, A.; Echevarria, G.; Tibbett, M. Delimiting nickel hyperaccumulation: Implications for phytomining and soil chemistry. Plant Soil 2023, 476, 67–82. [Google Scholar]

- Broadhurst, C.L.; Chaney, R.L. Growth and metal accumulation of an alyssum murale nickel hyperaccumulator ecotype o-cropped with alyssum montanum and perennial ryegrass in Serpentine soil. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, M.; Ali, S.; Zia ur Rehman, M.; Adrees, M.; Arshad, M.; Qayyum, M.F. Mechanisms of metal exclusion and tolerance in crop plants grown on contaminated soils. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 402, 123535. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, W.; Aamer, M.; Chattha, M.U.; Haiying, T.; Shahzad, B. Plant strategies for metal tolerance and exclusion under contaminated environments. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 249, 114396. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H. Uptake and translocation of barium and strontium in plants: Mechanisms and environmental implications. Chemosphere 2022, 291, 133003. [Google Scholar]

- White, P.J. The pathways of calcium movement to the xylem. J. Exp. Bot. 2001, 52, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nepal, A.; Antonious, G.F.; Bebe, F.N.; Webster, T.C.; Gyawali, B.R.; Neupane, B. Heavy metal accumulation in three varieties of mustard grown under five soil management practices. Environments 2024, 11, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.; Shamshad, S.; Rafiq, M.; Khalid, S.; Bibi, I.; Niazi, N.K.; Dumat, C.; Rashid, M.I. Chromium speciation, bioavailability, uptake, toxicity and detoxification in soil–plant system: A review. Chemosphere 2017, 178, 513–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.; Cao, X.; Zhou, Q.; Ma, L.Q. Accumulation of Pb, Cu, and Zn in native plants growing on a contaminated Florida site. Sci. Total Environ. 2006, 368, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, D.; Kumar, C. Biotechnological advances in bioremediation of heavy metals contaminated ecosystems: An overview with special reference to phytoremediation. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 11, 843–872. [Google Scholar]

- Rizwan, M.; Ali, S.; Rizvi, H.; Rinklebe, J.; Tsang, D.C.W.; Meers, E.; Ok, Y.S.; Ishaque, W. Phytomanagement of heavy metals in contaminated soils using sunflower: A review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 46, 1498–1528. [Google Scholar]

- Seregin, I.V.; Kozhevnikova, A.D. Nickel toxicity and tolerance in higher plants. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2006, 53, 257–277. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, J.L. Cellular mechanisms for heavy metal detoxification and tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Initial Metal Conc. in Soil | Unit | Values | CV (%) | FAO/WHO Limit (mg·kg−1) [38,39] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cobalt | mg·kg−1 | 14.7 ± 1.4 | 19 | 50 |

| Total lead | mg·kg−1 | 41.6 ± 3.8 | 18.3 | 50–85 |

| Total chromium | mg·kg−1 | 49.8 ± 8.2 | 32.9 | 75–100 |

| Total manganese | mg·kg−1 | 1059 ± 125 | 23.6 | 2000 |

| Total nickel | mg·kg−1 | 27.1 ± 3.1 | 22.9 | 50 |

| Total zinc | mg·kg−1 | 203.8 ± 17.2 | 16.9 | 300–1000 |

| Total copper | mg·kg−1 | 32.5 ± 3.3 | 20.3 | 100–300 |

| Total boron | mg·kg−1 | 22.1 ± 3.1 | 28.1 | NA |

| Total barium | mg·kg−1 | 620.3 ± 41 | 13.2 | 100 |

| Total strontium | mg·kg−1 | 152 ± 4.9 | 6.4 | NA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yelikbayev, B.K.; Rysbekov, K.; Sankabayeva, A.; Baltabayeva, D.; Islam, R. Plant Accumulation of Metals from Soils Impacted by the JSC Qarmet Industrial Activities, Central Kazakhstan. Environments 2026, 13, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010064

Yelikbayev BK, Rysbekov K, Sankabayeva A, Baltabayeva D, Islam R. Plant Accumulation of Metals from Soils Impacted by the JSC Qarmet Industrial Activities, Central Kazakhstan. Environments. 2026; 13(1):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010064

Chicago/Turabian StyleYelikbayev, Bakhytzhan K., Kanay Rysbekov, Assel Sankabayeva, Dinara Baltabayeva, and Rafiq Islam. 2026. "Plant Accumulation of Metals from Soils Impacted by the JSC Qarmet Industrial Activities, Central Kazakhstan" Environments 13, no. 1: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010064

APA StyleYelikbayev, B. K., Rysbekov, K., Sankabayeva, A., Baltabayeva, D., & Islam, R. (2026). Plant Accumulation of Metals from Soils Impacted by the JSC Qarmet Industrial Activities, Central Kazakhstan. Environments, 13(1), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010064