DNA Metabarcoding of Soil Microbial Communities in a Postvolcanic Region: Case Study from Băile Lăzărești, Romania

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Field Campaigns

Atmospheric Gas Composition

2.3. DNA Extraction and Sequencing

2.4. Bioinformatics

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Data Analysis

- ○

- Bacteria: Proteobacteria

- ○

- Fungi: Ascomycota

- ○

- Bacteria: kingdom Bacteria

- ○

- Fungi: order Thelebolales

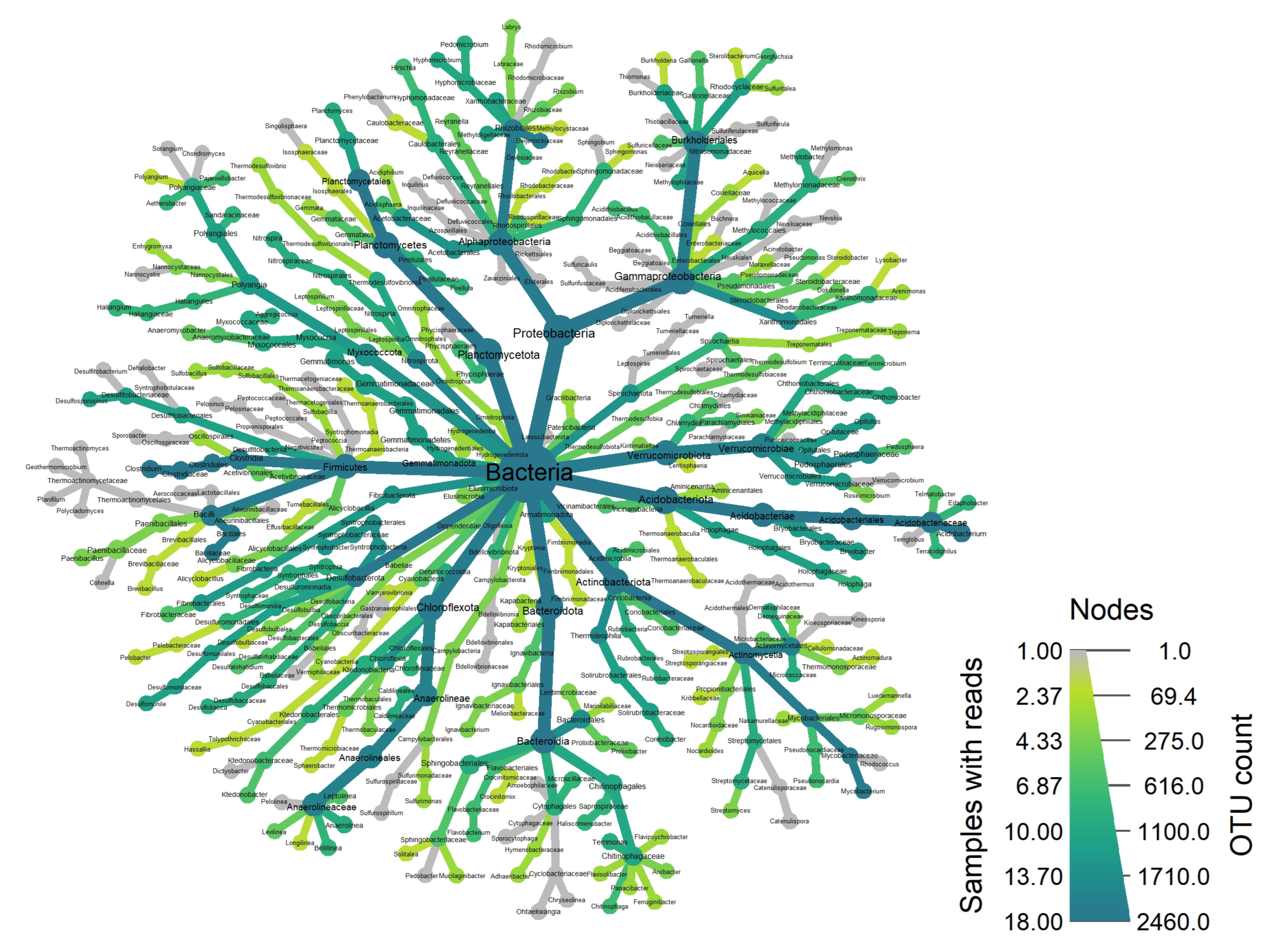

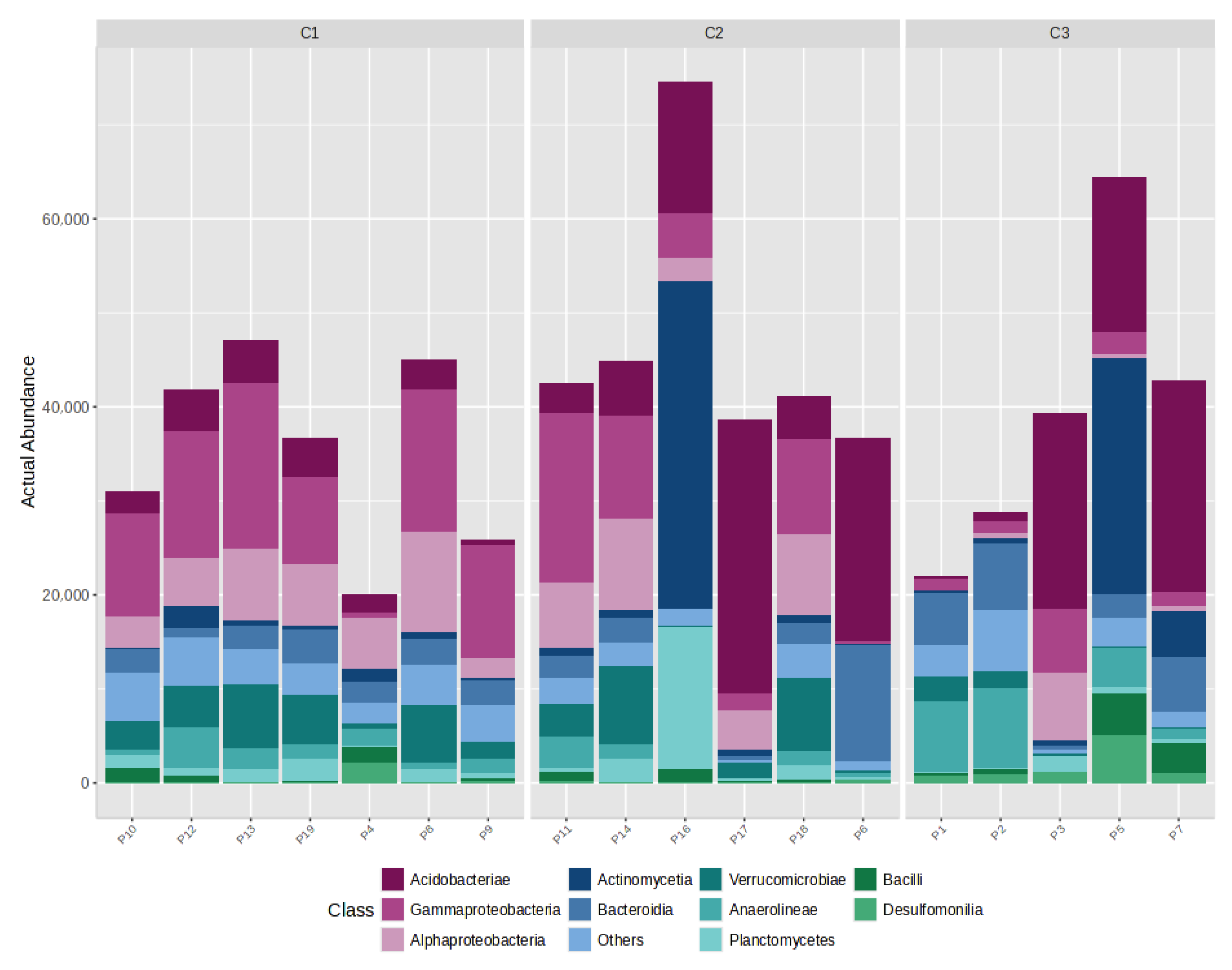

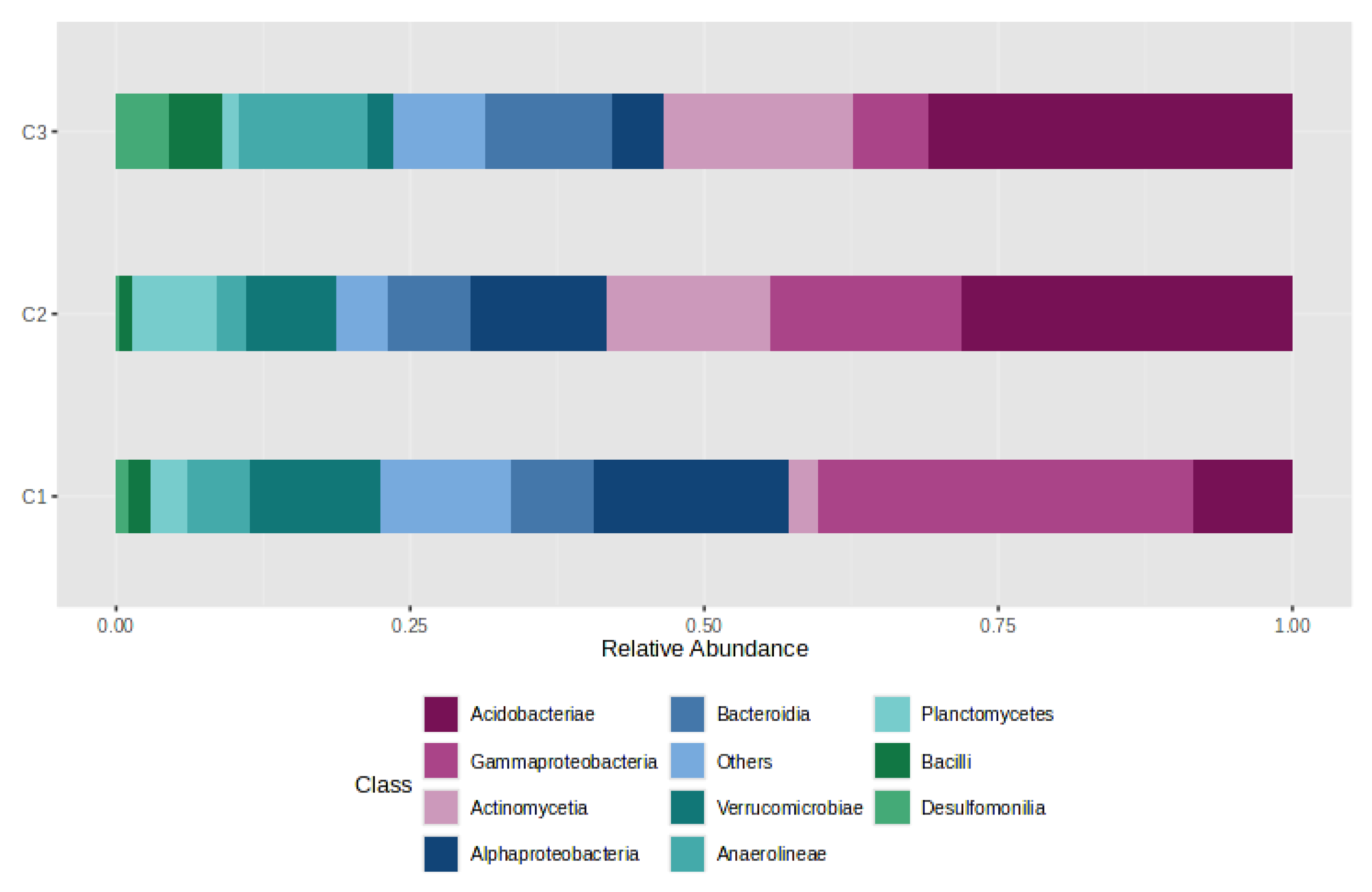

3.1.1. Bacteria

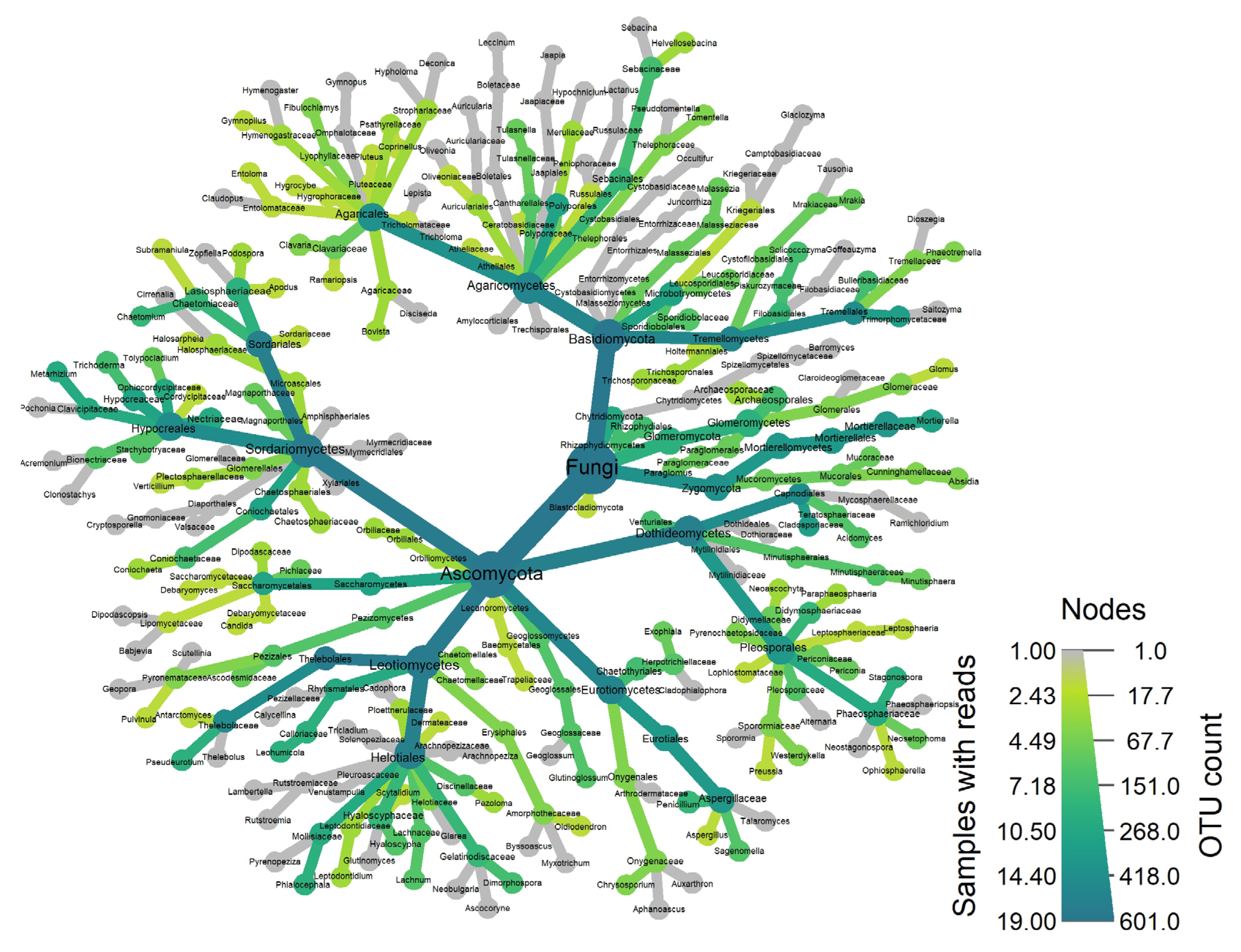

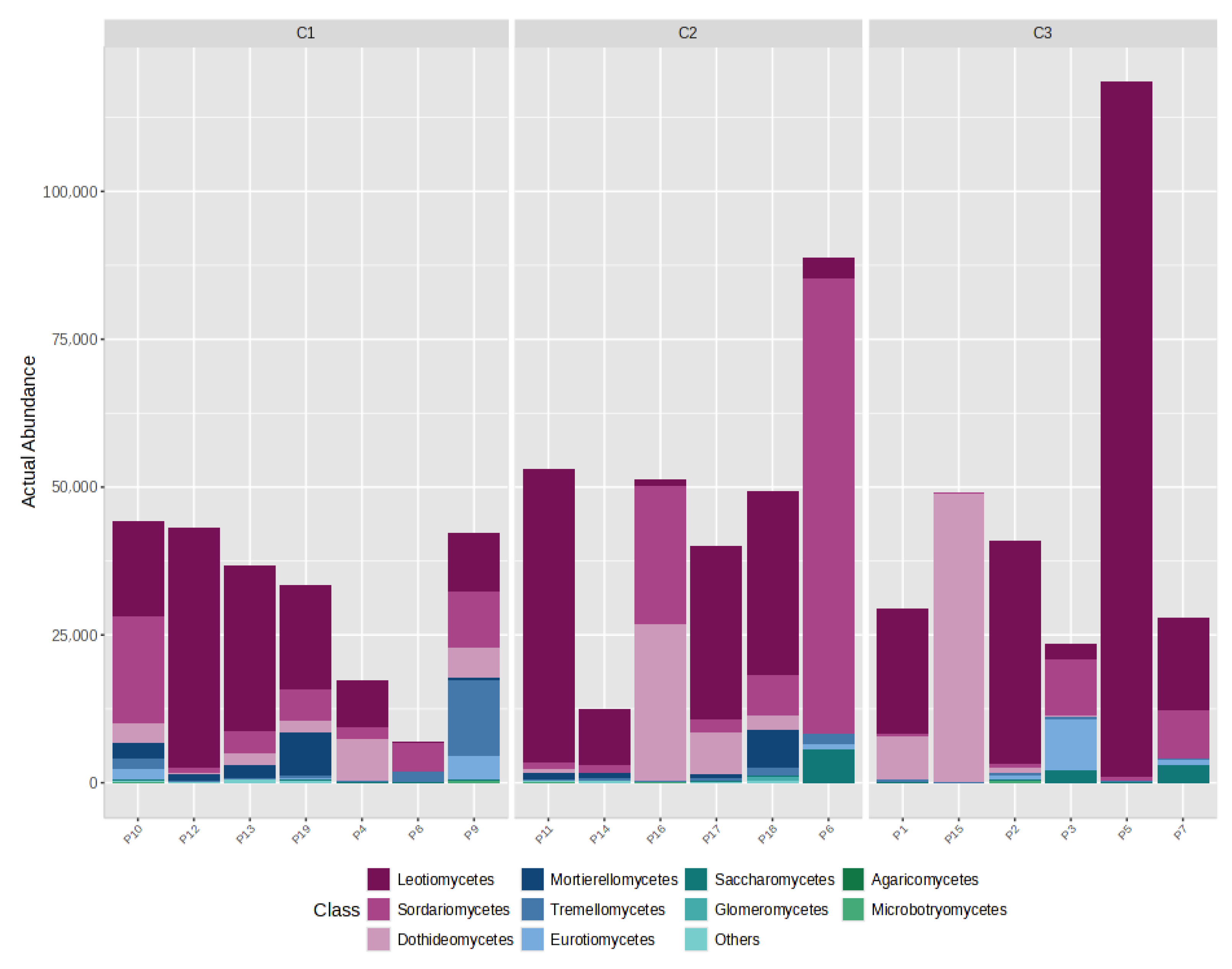

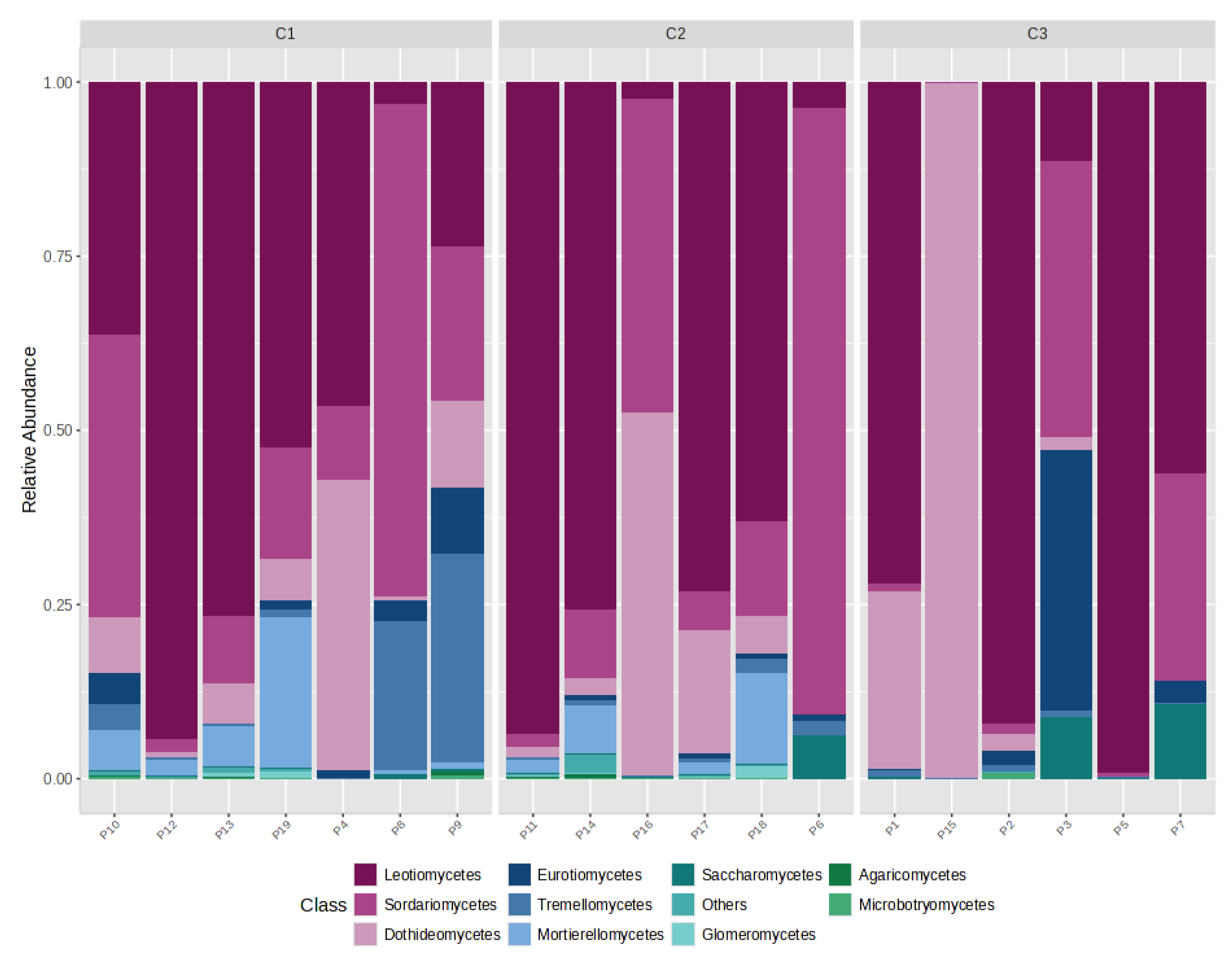

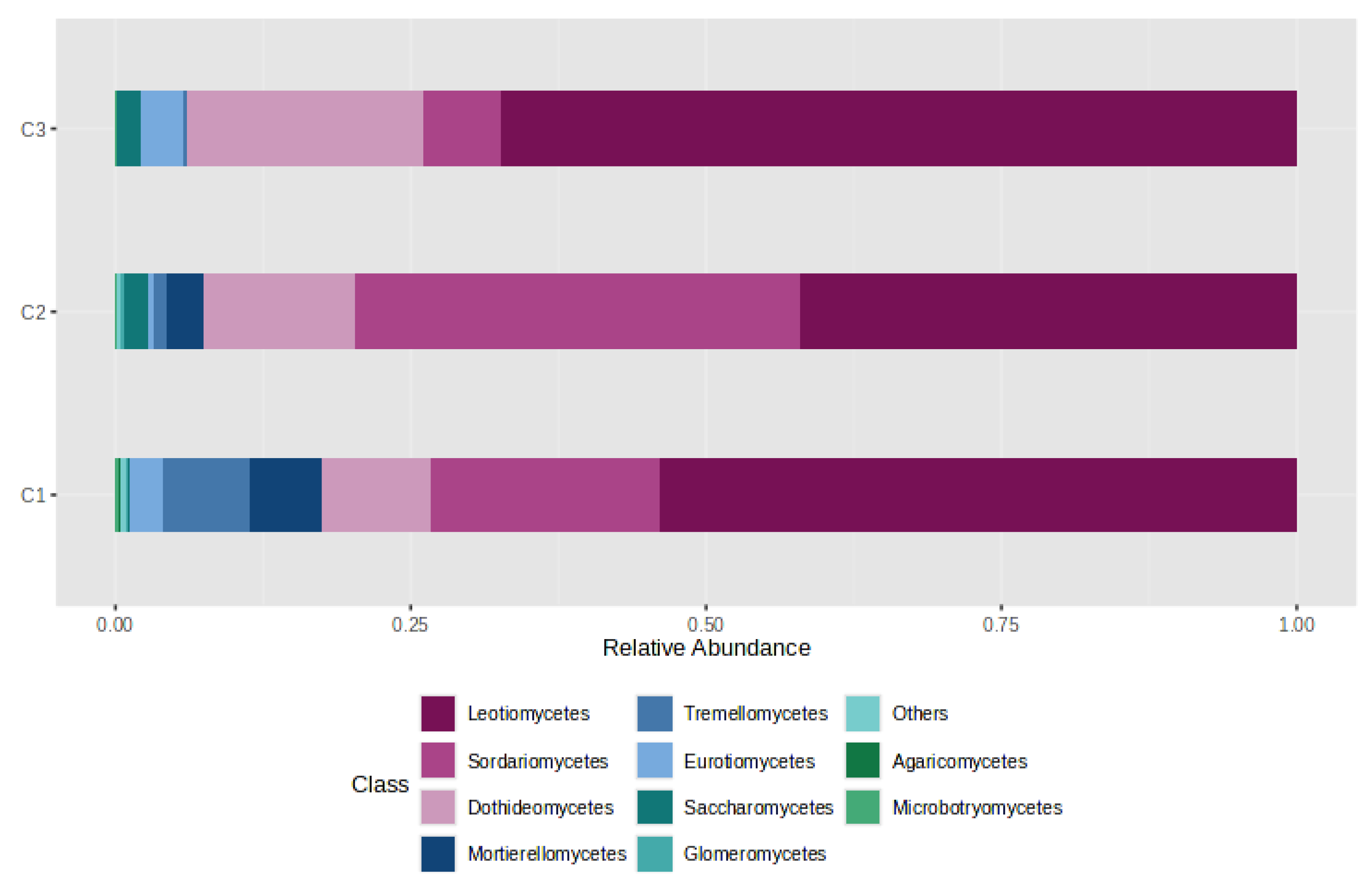

3.1.2. Fungi

4. Discussion

4.1. Quantitative Synthesis of the eDNA Set

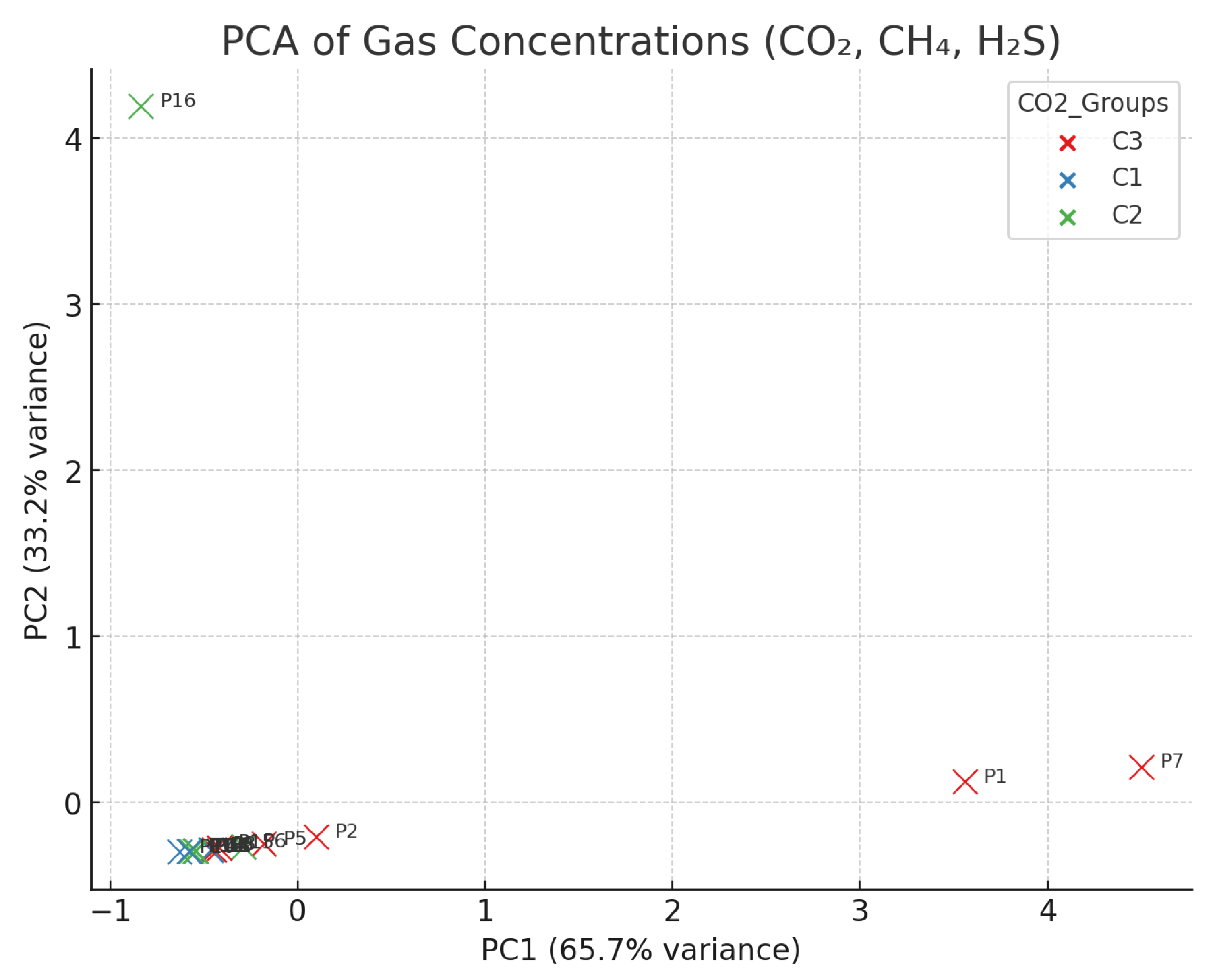

4.2. Geochemical Context

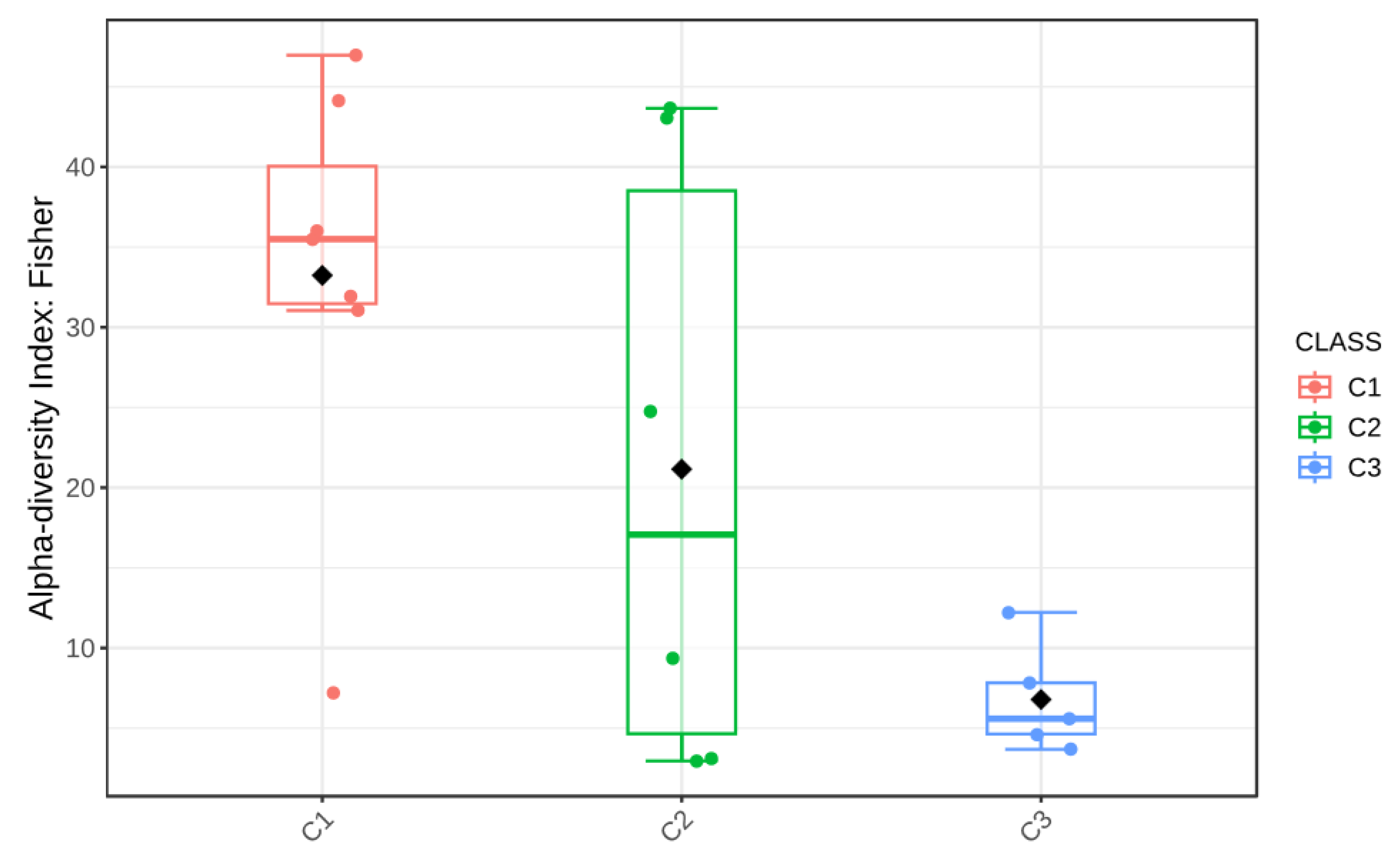

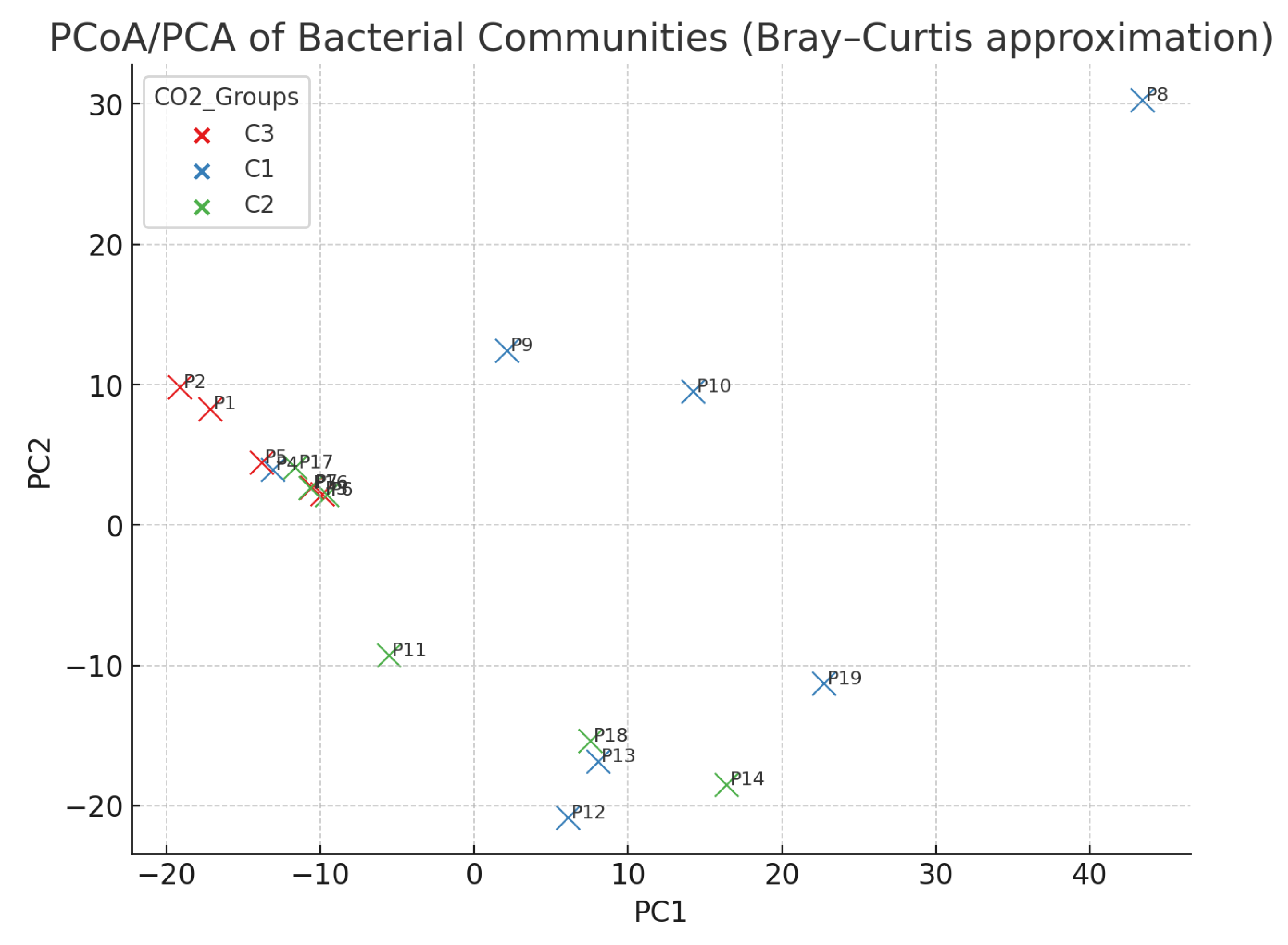

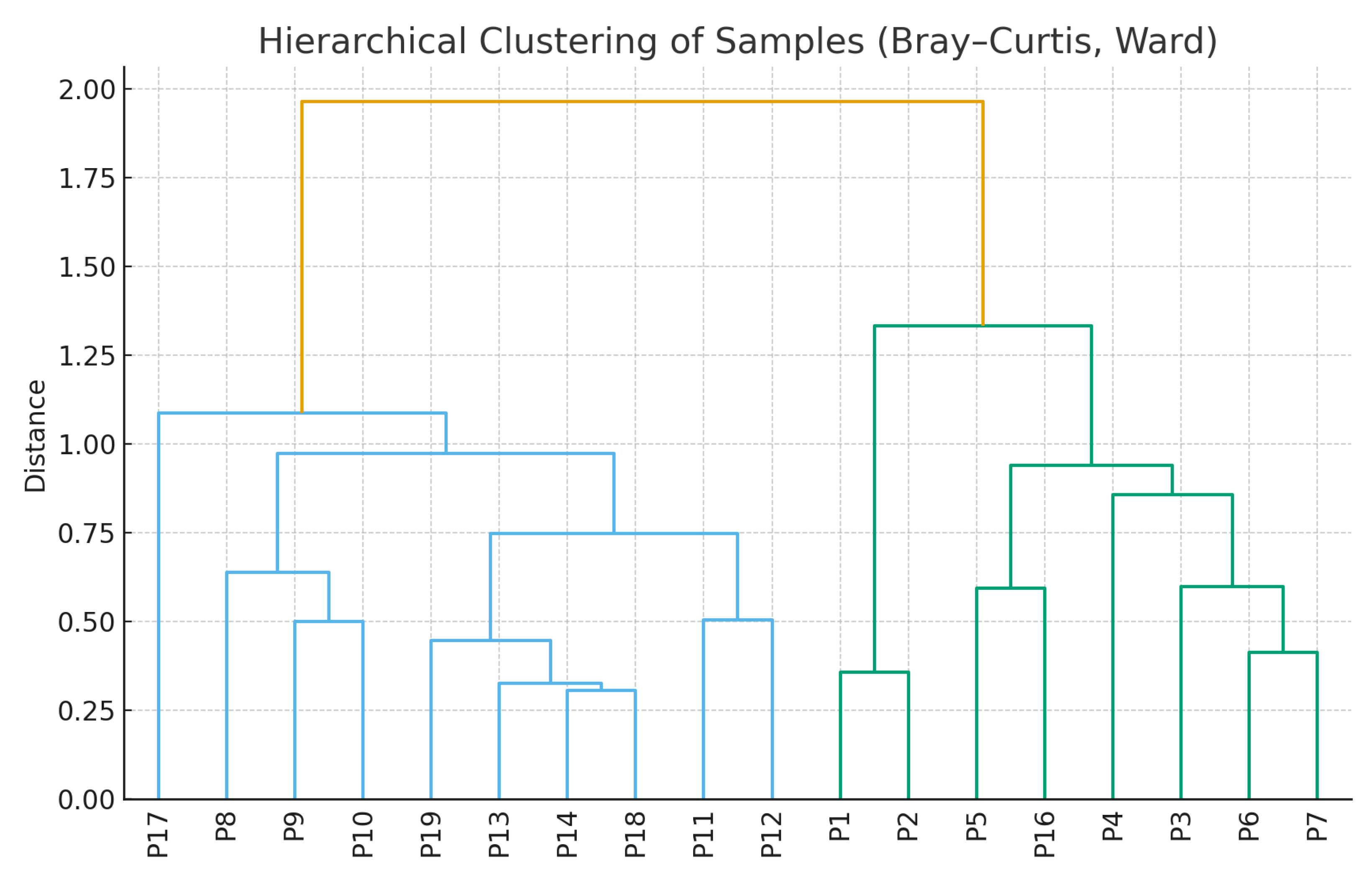

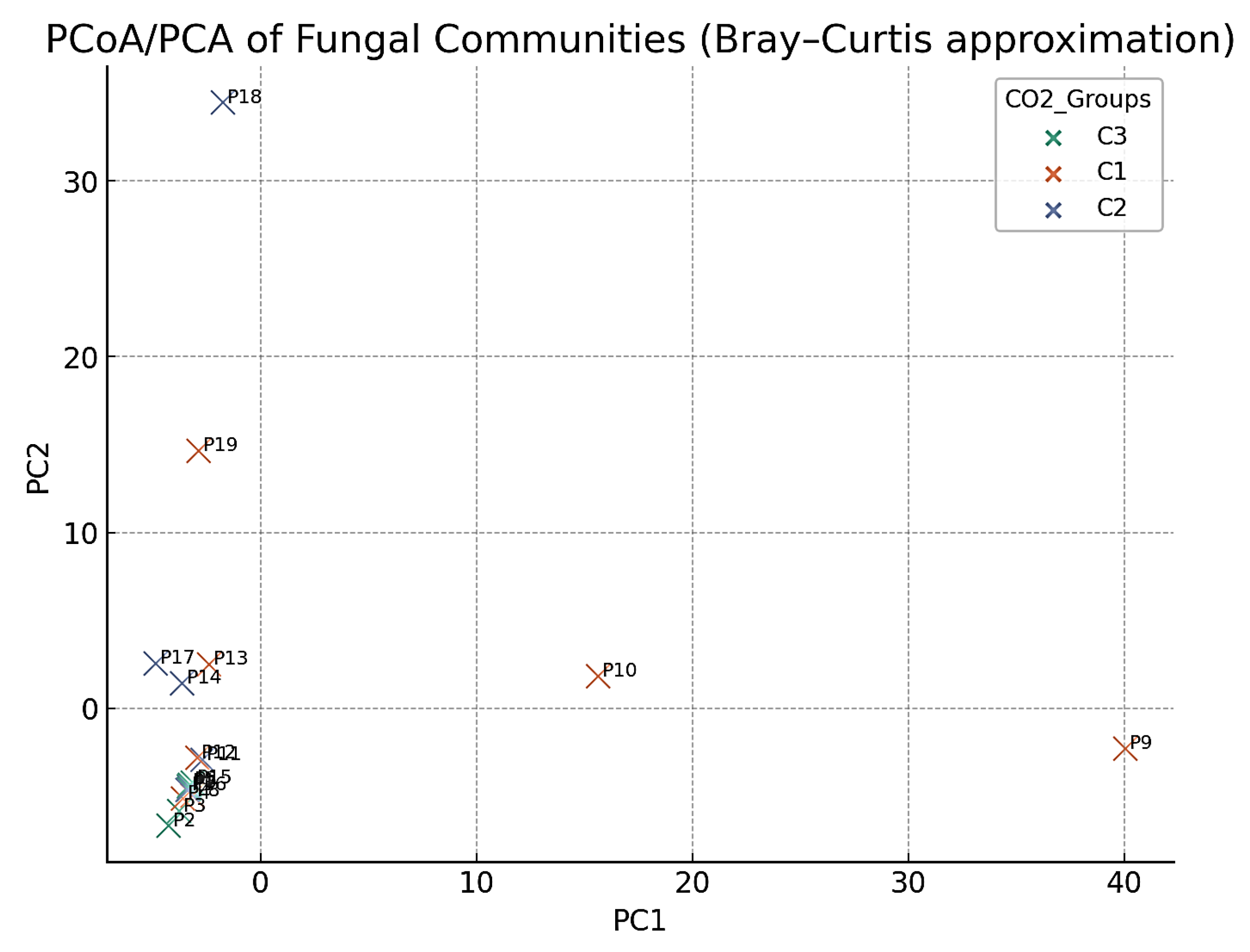

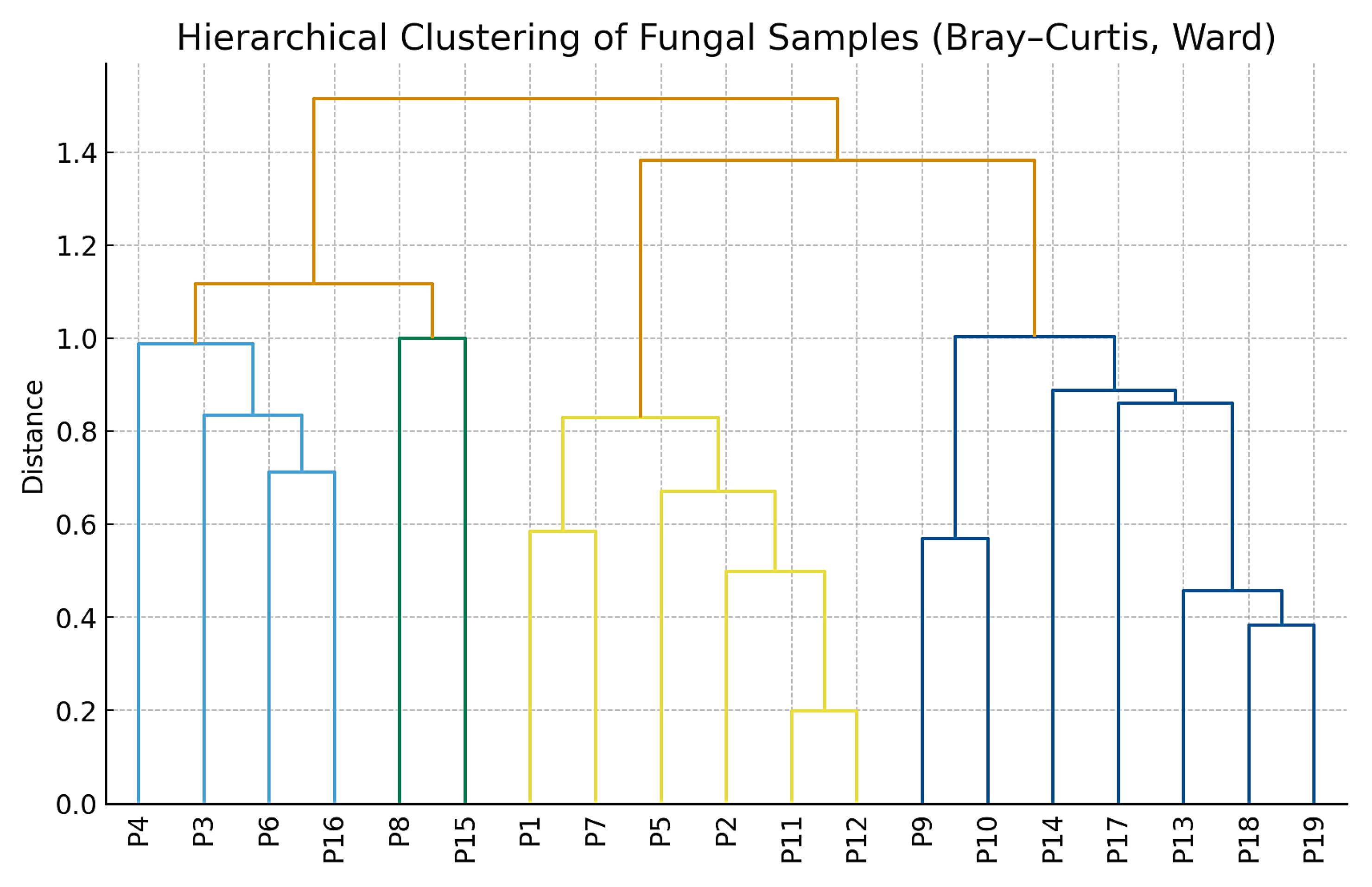

4.3. Distribution of Gases by CO2 Category (C1/C2/C3)

- C1 (n = 7): CO2 ≈ 99.66%, CH4 ≈ 0.27%, H2S ≈ 0.06%;

- C2 (n = 6): CO2 ≈ 54.13%, CH4 ≈ 45.85%, H2S ≈ 0.02%;

- C3 (n = 6): CO2 ≈ 99.34%, CH4 ≈ 0.64%, H2S ≈ 0.02%.

4.4. Gas–Bacteria Relationship

4.5. Gas–Fungi Relationship

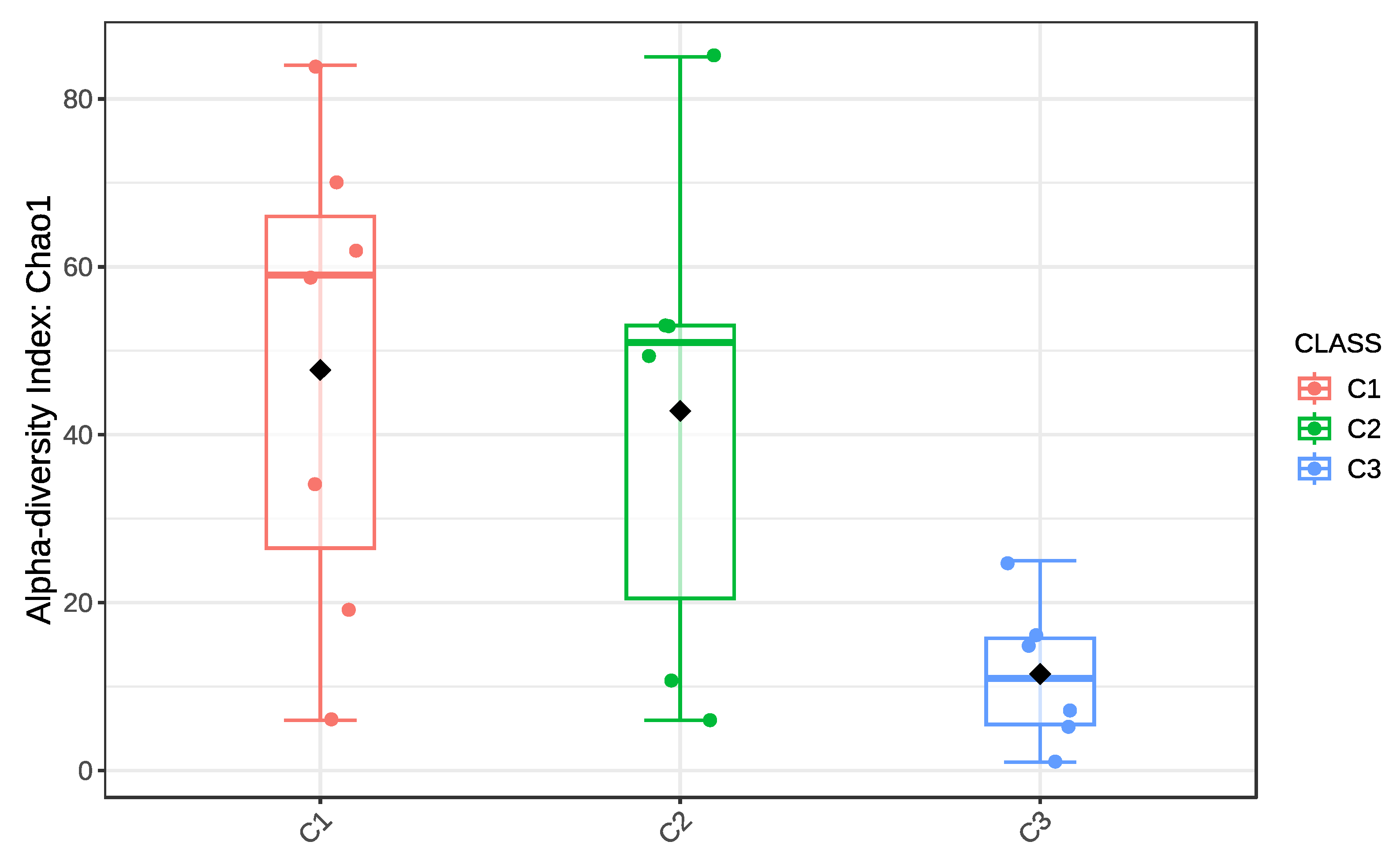

4.6. Statistical Significance of Diversity Patterns

4.7. Site-Scale Ecological Implications

4.8. Integration of Tracers

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; p. 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pachauri, R.K., Meyer, L.A., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; p. 151. [Google Scholar]

- West, J.M.; Pearce, J.M.; Bentham, M.; Maul, P. Environmental issues and the geological storage of CO2. Eur. Environ. 2005, 15, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- West, J.M.; Pearce, J.M.; Bentham, M.; Rochelle, C.; Maul, P.; Lombardi, S. Environmental Issues and the Geological Storage of CO2—A European Perspective. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Greenhouse Gas Control Technologies, Trondheim, Norway, 19–22 June 2006; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 1281–1286. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11573/417124 (accessed on 20 September 2025).[Green Version]

- Jossi, M.; Fromin, N.; Tarnawski, S.; Kohler, F.; Gillet, F.; Aragno, M.; Hamelin, J. How elevated pCO2 modifies total and metabolically active bacterial communities in the rhizosphere of two perennial grasses grown under field conditions. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2006, 55, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Beaubien, S.E.; Ciotoli, G.; Coombs, P.; Dictor, M.C.; Krüger, M.; Lombardi, S.; Pearce, J.M.; West, J.M. The impact of a naturally occurring CO2 gas vent on the shallow ecosystem and soil chemistry of a Mediterranean pasture (Latera, Italy). Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2008, 2, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppermann, B.I.; Michaelis, W.; Blumenberg, M.; Frerichs, J.; Schulz, H.M.; Schippers, A.; Beaubien, S.E.; Krüger, M. Soil microbial community changes as a result of long-term exposure to a natural CO2 vent. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2010, 74, 2697–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, J.C.; Hering, J.G. Factors affecting the dissolution kinetics of volcanic ash soils: Dependencies on pH, CO2, and oxalate. Appl. Geochem. 2004, 19, 1217–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macek, I.; Pfanz, H.; Francetic, V.; Batic, F.; Vodnik, D. Root respiration response to high CO2 concentrations in plants from natural CO2 springs. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2005, 54, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfanz, H.; Vodnik, D.; Wittmann, C.; Aschan, G.; Batic, F.; Turk, B.; Macek, I. Photosynthetic performance (CO2-compensation point, carboxylation efficiency, and net photosynthesis) of timothy grass (Phleum pratense L.) is affected by elevated carbon dioxide in post-volcanic mofette areas. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2007, 61, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, O.R.; Qafoku, N.P.; Cantrell, K.J.; Lee, G.; Amonette, J.E.; Brown, C.F. Geochemical implications of gas leakage associated with geologic CO2 storage—A qualitative review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humez, P.; Négrel, P.; Lagneau, V.; Lions, J.; Kloppmann, W.; Gal, F.; Millot, R.; Guerrot, C.; Flehoc, C.; Widory, D.; et al. CO2–water–mineral reactions during CO2 leakage: Geochemical and isotopic monitoring of a CO2 injection field test. Chem. Geol. 2014, 368, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lions, J.; Devau, N.; de Lary, L.; Dupraz, S.; Parmentier, M.; Gombert, P.; Dictor, M.C. Potential impacts of leakage from CO2 geological storage on geochemical processes controlling fresh groundwater quality: A review. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2014, 22, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, M.F.; Altman, S.J.; Santillan, E.-F.U.; Bennett, P.C. Interplay between microorganisms and geochemistry in geological carbon storage. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2016, 47, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beulig, F.; Urich, T.; Nowak, M.; Trumbore, S.E.; Gleixner, G.; Gilfillan, G.D.; Küsel, K. Altered carbon turnover processes and microbiomes in soils under long-term extremely high CO2 exposure. Nat. Microbiol. 2016, 1, 15025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, J.B.; Thomas, B.C.; Alvarez, W.; Banfield, J.F. Metagenomic analysis of a high carbon dioxide subsurface microbial community populated by chemolithoautotrophs and bacteria and archaea from candidate phyla. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 1686–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Probst, A.J.; Castelle, C.J.; Singh, A.; Brown, C.T.; Anantharaman, K.; Sharon, I.; Hug, L.A.; Burstein, D.; Emerson, J.B.; Thomas, B.C.; et al. Genomic resolution of a cold subsurface aquifer community provides metabolic insights for novel microbes adapted to high CO2 concentrations. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 19, 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pricăjan, A. Mineral and Thermal Waters from Romania; Ed. Tehnica: Bucharest, Romania, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Pricăjan, A. Therapeutic Mineral Substances from Romania; Scientific and Encyclopedic Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Karátson, D.; Veres, D.; Gertisser, R.; Magyari, E.K.; Jánosi, C.; Hambach, U. Ciomadul (Csomád), The Youngest Volcano in the Carpathians; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Berner, Z.; Jánosi, C.; Péter, É. A Kelemen-Görgényi-Hargita vonulat ásványvizei [Mineral Waters of Călimani-Gurghiu-Harghita Mountain Chain]; Report for Harghita County Council; The Official Gazette of Romania: Harghita County, Romania, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Szakács, A.; Seghedi, I.; Pécskay, Z.; Mirea, V. Eruptive history of a low-frequency and low-output rate Pleistocene volcano, Ciomadul, South Harghita Mts., Romania. Bull. Volcanol. 2015, 77, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bálint-Bálint, L.; Magyari-Sáska, Z.; Irimuş, I.A.; Peteley, A.; Niţă, A. The Valuation of the Urban Ecotourism Potential of the Volcanic Geomorphohydrosite Băile Tuşnad in Harghita County, Romania. Mod. Geograph. 2024, 19, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kis, B.M.; Szalay, R.; Aiuppa, A.; Bitetto, M.; Palcsu, L.; Harangi, S. Compositional measurement of gas emissions in the Eastern Carpathians (Romania) using the multi-GAS instrument: Approach for in situ data gathering at non-volcanic areas. J. Geochem. Explor. 2022, 240, 107051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tămaș, D.M.; Kis, B.M.; Tămaș, A.; Szalay, R. Identifying CO2 Seeps in a Long-Dormant Volcanic Area Using Uncrewed Aerial Vehicle-Based Infrared Thermometry: A Qualitative Study. Sensors 2022, 22, 2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnár, K.; Czuppon, G.; Palcsu, L.; Benkó, Z.; Lukács, R.; Kis, B.-M.; Németh, B.; Harangi, S. Noble gas geochemistry of phenocrysts from the Ciomadul volcanic dome field (Eastern Carpathians). Lithos 2021, 394–395, 106152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOAA. Global Monitoring Laboratory—Annual Greenhouse Gas Index. 2023. Available online: https://gml.noaa.gov/ccgg/ (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Anderson, M.J.; Gorley, R.N.; Clarke, K.R. PERMANOVA+ for PRIMER: Guide to Software and Statistical Methods; PRIMER-E Ltd.: Plymouth, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.T.; Ryan, P.D. PAST: Paleontological Statistics Software Package for Education and Data Analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001, 4, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Dhariwal, A.; Chong, J.; Habib, S.; King, I.L.; Agellon, L.B.; Xia, J. MicrobiomeAnalyst: A web-based tool for comprehensive statistical, visual and meta-analysis of microbiome data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W180–W188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Deng, H.; Wang, W.; Han, F.; Li, C.; Zhang, H.; Dai, Z. Impact of naturally leaking carbon dioxide on soil properties and ecosystems in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ham, B.; Choi, B.-Y.; Chae, G.-T.; Kirk, M.F.; Kwon, M.J. Geochemical influence on microbial communities at CO2-leakage analog sites. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beulig, F.; Heuer, V.B.; Akob, D.M.; Viehweger, B.; Elvert, M.; Herrmann, M.; Küsel, K. Carbon flow from volcanic CO2 into soil microbial communities of a wetland mofette. ISME J. 2015, 9, 746–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Kämpf, H.; Bussert, R.; Krauze, P.; Horn, F.; Nickschick, T.; Alawi, M. Influence of CO2 degassing on the microbial community in a dry mofette field in Hartoušov, Czech Republic (Western Eger Rift). Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhalnina, K.; Dias, R.; de Quadros, P.D.; Davis-Richardson, A.; Camargo, F.A.; Clark, I.M.; Triplett, E.W. Soil pH determines microbial diversity and composition in the Park Grass Experiment. Microb. Ecol. 2015, 69, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhalnina, K.; de Quadros, P.D.; Camargo, F.A.; Triplett, E.W. Drivers of archaeal ammonia-oxidizing communities in soil. Front. Microbiol. 2012, 3, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.T.; Robeson, M.S.; Lauber, C.L.; Hamady, M.; Knight, R.; Fierer, N. A comprehensive survey of soil acidobacterial diversity using pyrosequencing and clone library analyses. ISME J. 2009, 3, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Ka, J.O.; Cho, J.C. Members of the phylum Acidobacteria are dominant and metabolically active in rhizosphere soil. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2008, 285, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, G.T.; Bates, S.T.; Eilers, K.G.; Lauber, C.L.; Caporaso, J.G.; Walters, W.A.; Knight, R.; Fierer, N. The under-recognized dominance of Verrucomicrobia in soil bacterial communities. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 1450–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosser, J.I.; Bohannan, B.J.M.; Curtis, T.P.; Ellis, R.J.; Firestone, M.K.; Freckleton, R.P.; Green, J.L.; Green, L.E.; Killham, K.; Lennon, J.J.; et al. The role of ecological theory in microbial ecology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007, 5, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Miera, L.E.S.; Arroyo, P.; de Luis Calabuig, E.; Falagán, J.; Ansola, G. High-throughput sequencing of 16S rRNA genes of soil bacterial communities from a naturally occurring CO2 gas vent. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2014, 29, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierer, N.; Jackson, R.B. The diversity and biogeography of soil bacterial communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauber, C.L.; Hamady, M.; Knight, R.; Fierer, N. Pyrosequencing-based assessment of soil pH as a predictor of soil bacterial community structure at the continental scale. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 5111–5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Power, J.F.; Carere, C.R.; Lee, C.K.; Wakerley, G.L.; Evans, D.W.; Button, M.; Stott, M.B. Microbial biogeography of 925 geothermal springs in New Zealand. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousk, J.; Bååth, E.; Brookes, P.C.; Lauber, C.L.; Lozupone, C.; Caporaso, J.G.; Fierer, N. Soil bacterial and fungal communities across a pH gradient in an arable soil. ISME J. 2010, 4, 1340–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Kim, C.Y.; Kirk, M.F.; Chae, G.; Kwon, M.J. Effects of natural non-volcanic CO2 leakage on soil microbial community composition and diversity. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 862, 160754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, M.; Jones, D.; Frerichs, J.; Oppermann, B.I.; West, J.; Coombs, P.; Green, K.; Barlow, T.; Lister, B.; Shaw, R.; et al. Effects of elevated CO2 concentrations on the vegetation and microbial populations at a terrestrial CO2 vent at Laacher See, Germany. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2011, 5, 1093–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, M.; West, J.; Frerichs, J.; Oppermann, B.; Dictor, M.-C.; Jouliand, C.; Jones, D.; Coombs, P.; Green, K.; Pearce, J.; et al. Ecosystem effects of elevated CO2 concentrations on microbial populations at a terrestrial CO2 vent at Laacher See, Germany. Energy Procedia 2009, 1, 1933–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziogou, F.; Gemeni, V.; Koukouzas, N.; de Angelis, D.; Libertini, S.; Beaubien, S.E.; Lombardi, S.; West, J.M.; Jones, D.G.; Coombs, P.; et al. Potential Environmental Impacts of CO2 Leakage from the Study of Natural Analogue Sites in Europe. Energy Procedia 2013, 37, 3521–3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.L.; Steven, M.D.; Jones, D.G.; West, J.M.; Coombs, P.; Green, K.A.; Barlow, T.S.; Breward, N.; Gwosdz, S.; Krüger, M.; et al. Environmental impacts of CO2 leakage: Recent results from the ASGARD facility, UK. Energy Procedia 2013, 37, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feitz, A.; Jenkins, C.; Schacht, U.; McGrath, A.; Berko, H.; Schroder, I.; Noble, R.; Kuske, T.; George, S.; Heath, C.; et al. An assessment of near surface CO2 leakage detection techniques under Australian conditions. Energy Procedia 2014, 63, 3891–3906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwosdz, S.; West, J.M.; Jones, D.; Rakoczy, J.; Green, K.; Barlow, T.; Blöthe, M.; Smith, K.; Steven, M.; Krüger, M. Long-term CO2 injection and its impact on near-surface soil microbiology. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2016, 92, fiw193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Target | Number of OTUs | Phylum | Class | Order | Family | Genus | Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | 2463 | 68.3% | 53.8% | 39.3% | 27.8% | 11.3% | 2.1% |

| Fungi | 601 | 98.8% | 89.7% | 79.7% | 62.6% | 31.4% | 11.3% |

| Sample | Profile | CH4 (ppm) | H2S (ppm) | CO2 (ppm) | CO2 Categories |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 1P | 275.2008 | 7.37361 | 42,653.92 | C3 |

| P2 | 1P | 82.63361 | 0.453123 | 13,162.42 | C3 |

| P3 | 1P | 4.494262 | 0.393549 | 3199.084 | C3 |

| P4 | 1P | 2.43252 | 0.542659 | 601.6707 | C1 |

| P5 | 1P | 36.94797 | 0.939593 | 5396.768 | C3 |

| P6 | 1P | 15.77377 | 1.096336 | 2531.079 | C2 |

| P7 | 1P | 318.7418 | 10.11688 | 46,220.71 | C3 |

| P8 | 1P | 2.33252 | 0.765073 | 992.7963 | C1 |

| P9 | 1P | 2.1416 | 0.829536 | 631.2909 | C1 |

| P10 | 1P | 2.135075 | 0.250425 | 485.4114 | C1 |

| P11 | 2P | 1.963934 | 0.374443 | 1505.181 | C2 |

| P12 | 2P | 2.024793 | 0.366752 | 929.5848 | C1 |

| P13 | 2P | 1.887705 | 0.344893 | 977.153 | C1 |

| P14 | 2P | 2.447934 | 0.336711 | 1608.869 | C2 |

| P15 | 2P | 19.968 | 0.44908 | 3447.992 | C3 |

| P16 | 2P | 8271.474 | 0.384769 | 1456.66 | C2 |

| P17 | 2P | 3.504132 | 0.33995 | 1173.752 | C2 |

| P18 | 2P | 1.856911 | 0.349366 | 1520.143 | C2 |

| P19 | 2P | 1.858537 | 0.382748 | 785.9752 | C1 |

| Analysis | Test | Result | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha diversity (Bacteria, Chao1) | Welch’s ANOVA + post hoc | Significant | 0.017 |

| Alpha diversity (Bacteria, Fisher) | Welch’s ANOVA + post hoc | Significant | 0.023 |

| Alpha diversity (Fungi, Chao1) | Welch’s ANOVA | Not significant | 0.11 |

| Alpha diversity (Fungi, Fisher) | Welch’s ANOVA | Not significant | 0.09 |

| Beta diversity (Bacteria) | PERMANOVA (Bray–Curtis, 999 permutations) | Significant | 0.001 |

| Beta diversity (Fungi) | PERMANOVA (Bray–Curtis, 999 permutations) | Significant (weak) | 0.045 |

| Domain | Genus | Trend Under High CO2 | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Acidobacterium, Granulicella | ↑ Enriched in acidic, CO2-rich soils | [37,38] |

| Bacteria | Streptomyces, Nocardia | ↑ Tolerant, degrade complex OM | [39] |

| Bacteria | Flavobacterium, Chitinophaga | ↑ Adapted to C-rich, anoxic niches | [40] |

| Bacteria | Rhizobium, Pseudomonas | ↓ Sensitive to acidity/anoxia | [33,35] |

| Fungi | Thelebolus | ↑ Ubiquitous in mofettas | [33,34] |

| Fungi | Mortierella | ↓ Reduced under high CO2 | [31] |

| Fungi | Cladosporium | ↑ Tolerant, stress-adapted | [32] |

| Fungi | Cryptococcus, Vishniacozyma | ↓ Sensitive, aerobic niches | [41] |

| Site (Reference) | Max CO2 Flux/Conc. | Vegetation Response |

|---|---|---|

| Latera, Italy [6] | >2000–3000 g m−2 d−1, >95% soil CO2 | No vegetation in vent core; transition zone with grasses/clover |

| Laacher See, Germany [47,48] | Up to 95% soil CO2 | Vegetation absent directly above vents |

| Florina, Greece [49] | Localized vents with high soil CO2 (>20%) | Grassland degraded; plant diversity reduced near vents |

| ASGARD, UK [50] | Injected 2–50% soil CO2 | Crop stress, reduced biomass at >15% CO2 |

| Australia [51] | Fluxes >10,000 g m−2 d−1 | Vegetation death in high flux zones |

| Daepyeong, Korea [46] | 29% soil CO2‚ in high flux group | Lower pH soils, vegetation stress and reduced cover |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dudu, A.-C.; Pavel, A.B.; Avram, C.; Iordache, G.; Dragoș, A.-G.; Dobre, O.; Sava, C.-Ș.; Stelea, L. DNA Metabarcoding of Soil Microbial Communities in a Postvolcanic Region: Case Study from Băile Lăzărești, Romania. Environments 2025, 12, 344. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments12100344

Dudu A-C, Pavel AB, Avram C, Iordache G, Dragoș A-G, Dobre O, Sava C-Ș, Stelea L. DNA Metabarcoding of Soil Microbial Communities in a Postvolcanic Region: Case Study from Băile Lăzărești, Romania. Environments. 2025; 12(10):344. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments12100344

Chicago/Turabian StyleDudu, Alexandra-Constanța, Ana Bianca Pavel, Corina Avram, Gabriel Iordache, Andrei-Gabriel Dragoș, Oana Dobre, Constantin-Ștefan Sava, and Lia Stelea. 2025. "DNA Metabarcoding of Soil Microbial Communities in a Postvolcanic Region: Case Study from Băile Lăzărești, Romania" Environments 12, no. 10: 344. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments12100344

APA StyleDudu, A.-C., Pavel, A. B., Avram, C., Iordache, G., Dragoș, A.-G., Dobre, O., Sava, C.-Ș., & Stelea, L. (2025). DNA Metabarcoding of Soil Microbial Communities in a Postvolcanic Region: Case Study from Băile Lăzărești, Romania. Environments, 12(10), 344. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments12100344