Conceptual Design of an Urban Pocket Park Located in the Site of the Occurrence of a Nineteenth-Century Chapel Using Representatives of Local Xerothermic Vegetation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Natural Conditions of the Study Area

2.2. Brief Overview of the History of the Site

2.3. Basic Data on Xerothermic Vegetation

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Basic Characteristic of Area to Be Developed

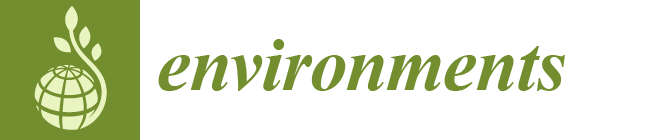

3.2. A Dendrological Inventory

3.3. Basic Analysis of the Communication System

3.4. Basic Analysis of Functional Zones

3.5. Compositional and Visual Analysis

3.6. Analysis of the Social Survey

4. Results

4.1. Results of Social Survey

4.2. Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats—SWOT Analysis of the Area in Question

4.3. The Valorization and Basic Guidelines

4.4. The Guidelines for Development and Small Architecture

4.5. The Guidelines for the Functional and Compositional Layout

4.6. Concept of Design

4.7. Planting Guidelines

4.8. Projected Functions of Development Area

4.9. Some Additional Details of Design

4.10. The Small Architecture

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Castaldo, V.L.; Pisello, A.L.; Pigliautile, I.; Piselli, C.; Cotana, F. Microclimate and air quality investigation in historic hilly urban areas: Experimental and numerical investigation in central Italy. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 33, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, M.C.; Flucher, J.M.; McKeon, T.; Branas, C. Urban Green Space and Its Impact On Human Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aerts, R.; Honnay, O.; van Nieuwenhuyse, A. Biodiversity and human health: Mechanisms and evidence of the positive health effects of diversity in nature and green spaces. Br. Med. Bull. 2018, 127, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semeraro, T.; Scarano, A.; Buccolieri, R.; Santino, A.; Aarrevaara, E. Planning of Urban Green Spaces: An Ecological Perspective on Human Benefits. Land 2021, 10, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alakavuk, E.; Cinar Umdu, D. Urban Open Therapy Gardens in EU Cities Mission: Izmir Union Park Proposal. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikin, K.; Beaty, R.M.; Lindenmayer, D.V.; Knight, E.; Fisher, J.; Manning, A.D. Pocket parks in a compact city: How do birds respond to increasing residential density? Landsc. Ecol. 2013, 18, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordh, H.; Østby, K. Pocket parks for people—A study of park design and use. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdy, M.; Plaku, R. Pockect Parks: Urban Living Rooms for Urban Regeneration. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2021, 9, 747–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzysztofik, S.; Galoch, A. Pocket Parks in Łódź as an element of improving urban resilience in the city centre. Build. Sci. 2022, 10, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, F.; Pioppi, B.; Pisello, A.L. Pocket parks for human-centered climate change resilience: Microclimate field tests and multi-domain comfort analysis through portable sensing techniques and citizens’ science. Energy Build. 2022, 260, 111918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornal-Pienak, B.; Bihuňová, M. Evaluation of current landscape architecture approaches in chosen cities in Poland and Slovakia. Acta Hortic. Regiotec. 2022, 25, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, F.; Cappa, F.; Spitzmiller, R.; Ferrero, M. Pocket parks towards more sustainable cities. Architectural, environmental and legal considerations towards an integrated framework: A cases study in the Mediterranean region. Envron. Chall. 2022, 7, 100402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Xie, M.; Zhao, J.; An, Y. What Affects the Use Flexibility of Pocket Parks? Evidence from Nanjing, China. Land 2022, 11, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surma, M. Green Infrastucture Planning as a part of Sustainable Urban Development − case studies of Copenhagen and Wroclaw. Proc. Lat. Univ. Agric. Landsc. Archit. Art 2013, 3, 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Labuz, R. Pocket Park—A New Type of Green Public Space in Kraków (Poland). IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 471, 11218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbisz, A.; Urbisz, A.; Błażyca, B. Rock vascular plant species of The Kraków-Częstochowa Upland. Thaszisza J. Bot. 2011, 21, 207–2014. Available online: https://www.upjs.sk/ (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Bomanowska, A.; Rewicz, A.; Krycinska, A. The transformation of vascular flora of limestone monadnocks by rock climbing. Life Sci. J. 2014, 11, 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Boroń, M.; Ociepińska, M.; Żeber-Dzikowska, I.; Gworek, B.; Kondzielski, I.; Chmielewski, J. Xerotermic pavements—A medow biodiversity richness. Jawarzno case study. Environ. Prot. Nat. Res. 2019, 30, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochman, A.; Matyszkiewicz, J.; Wasilewski, M. Siliceous rocks from the southern part of the Kraków-Częstochowa Upland (Southern Poland) as potential raw materials in the manufacture of stone tools—A characterization and possibilities of identification. J. Arch. Sci. Rep. 2020, 3, 102195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudniak, J. Comparison of local solar radiation parameters with the data from a typical meteorological year. Therm. Sci. Eng. Progress 2000, 16, 100465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żemła-Siesicka, A.; Myga-Piątek, U. Persistence Assessment of Czestochowa Upland: A Case Study of Ogrodzieniec, Poland. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staszczak, J. Operating Opencast Mines of selected groups in the Silesian Voivodeship Agaist a Background of Water Environments and Possibilities of Waste Placing. J. Pol. Mineral Eng. Soc. 2020, 12, 147–152. [Google Scholar]

- Secrets of the Chapel in Stradom District of Czestochowa City. Available online: http://historia.blachownia.com/2018/01/10/tajemnice-kapliczki-na-stradomiu/ (accessed on 25 November 2022). (In Polish).

- Roleček, J.; Dřevojan, P.; Hájková, P.; Hájek, M. Report of new maxima of fine-scale vascular plant species richness recorded in East-Central European semi-dry grasslands. Tuxenia 2019, 39, 423–431. [Google Scholar]

- Willner, W.; Roleček, J.; Korolyuk, A.; Dengler, J.; Chytrý, M.; Janišova, M.; Lengyel, A.; Aćić, S.; Becker, T.; Ćuk, M.; et al. Formalized classification of semi-dry grasslands in central and eastern Europe. Preslia 2019, 91, 25–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pietro, R.; Fortini, P.; Misano, G.; Terzi, M. Phytosociology of Atractylis cancellata and Micromeria microphylla communities in Southern Italy with insights on the xerotermic steno-Mediteranean grasslands high-rank syntaxa. Plant Sciol. 2021, 58, 133–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chytry, K.; Prokešová, H.; Duchoň, M.; Grulich, V.; Chytry, M.; Divíšek, J. Substrate associated biogeographical patterns in the north-western Pannonian forest-steppe. Preslia 2022, 94, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmanov, O.; Cabała, J.; Krzysztofik, R. Vegetation and Environmental Changes on Contaminated Soil Formed on Waste from an Historic Zn-Pb Ore-Washing Plant. Biology 2021, 10, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, P. Basaltic Outcrops as Centers of Diversity for Xerothermic Plants in the Sudetes Mountains (Central Europe). Diversity 2021, 13, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzwonko, Z.; Loster, S. Changes in plant species composition in abandoned and restores limestone grasslands-the effect of tree and shrub cutting. Act. Soc. Bot. Pol. 2008, 77, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cwener, A.; d Chmielowski, P. Factors determining changes of flora of xerotermic habitats in Skierbieszów Landscape Park (SE Poland). Ann. Univ. Marie Curie-Skłodowska 2012, LXII, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Łuszczyński, K.; Adamska, E.; Czerwik-Marcinkowska, J. Diversity Patterns of Macrofungi in Xerotermic Grasslands from the Nida Bassin (Małopolska Uppland, Southern Poland): A Case Study. Biology 2022, 11, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbisz, A. Why are some plant becoming extinct while others spreading? Pak. J. Bot. 2022, 54, 249–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesień, M.; Denisow, B. The share of nectariferous and polleniferous taxons in chosen patches of thermophilous grasslands of the Lublin Upland. Acta Agrobot. 2006, 59, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futa, B.; Kuklik, M.; Kajtoch, Ł.; Mazur, M.A.; Jaźwa, M.; Ścibior, R.; Wielgos, J. Enzymatic Activity of Soil on the Occurrence of the Endangered Beetle Cheilotoma musciformis (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) in Xerothermic Grasslands. Insects 2024, 15, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podgórka, M.; Łazarski, G. Impact of Secondary Succesion in the Xerotermic Grassland on the population of Eastern Pasque Flower (Pulsatilla patens)−Preliminary Studies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misztal, A.; Zarzycki, J.; Bedla, D. Habitat conditions of Sysimbrio-Stipetum capillate and Koelerio-Festucetum sulcate steppe plant association in the Ostoja Nidzińska specially protected area. Infrasruct. Ecol. Rur. Areas 2015, IV, 1363–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

|

|

| Opportunities | Threats |

|

|

| No. | Latin Name | National Name | Plant Height[cm] | Flower Color | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant material intended for the establishment of a flower meadow | |||||

| Plants that bloom from spring to summer | |||||

| 1 | Anthylis vulneraria L. | Przelot pospolity | 15–30 | yellow | [17,18] |

| 2 | Anthemis tinctoria L. | Rumian żółty | 20–30 | yellow | [17,18] |

| 3 | Alyssum montanum L. | Smagliczka pagórkowa | 20–35 | yellow | [17,18] |

| Plants that bloom from summer to autumn | |||||

| 4 | Achillea collina Becker ex Rchb | Krwawnik pagórkowy | 45–50 | white | [17,18] |

| 5 | Achillea millefolium subsp. pannonica | Krwawnik pannoński | 40–50 | white | [17,18] |

| 6 | Arabis hirsuta (L.) Scop | Gęsiówka szorstkowłosista | 15–30 | white | [17,18] |

| 7 | Galium cynanchicum (L.) Scop | Marzanka pagórkowa | 15–25 | white | [17,18] |

| 8 | Centaurea scabiosa L. | Chaber driakiewnik | 50–100 | pink | [18,24] |

| 9 | Dianthus cartusianorum L. | Goździk kartuzek | 20–40 | pink | [18,24] |

| 10 | Galium verum L. | Przytulia właściwa | 60–80 | yellow | [18,24] |

| 11 | Scabiosa ochroleuca L. | Driakiew żółta | 25–40 | yellow | [24,25] |

| 12 | Scabiosa canescens Walds&Kit | Driakiew wonna | 30–40 | pink | [24,25] |

| 13 | Thymus pulegioides L. | Macierzanka zwyczajna | 25–35 | pink | [24,25] |

| 14 | Veronica spicata L. | Przetacznik kłosowy | 20–45 | blue | [11,16] |

| 15 | Stachys recta L. | Czyściec prosty | 15–30 | yellow | [18,21] |

| Mix of grasses | |||||

| 16 | Avenula pratensis (L.) Dumort | Owsica łąkowa | 90–100 | green | [24,25] |

| 17 | Bromus erectus Huds | Stokłosa prosta | 45–100 | green | [25,26] |

| 18 | Bromus inermis Leyss | Stokłosa bezostna | 100–110 | green | [26,29] |

| 19 | Festuca rubra L. | Kostrzewa czerwona | 30–40 | green/red | [30,31] |

| 20 | Melica ciliata L. | Perłówka otrzęsiona | 45–80 | green/white | [30,31] |

| 21 | Stipa Joannis Čelak | Ostnica Jana | 50–80 | green/white | [31,33] |

| 22 | Stipa pulcherrima Köch | Ostnica powabna | 75–85 | green/white | [24,31] |

| 23 | Stipa capillata L. | Ostnica włosowata | 35–100 | green/white | [34,36] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kopeć, W.; Hanus-Fajerska, E.; Bylina, L. Conceptual Design of an Urban Pocket Park Located in the Site of the Occurrence of a Nineteenth-Century Chapel Using Representatives of Local Xerothermic Vegetation. Environments 2024, 11, 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments11110252

Kopeć W, Hanus-Fajerska E, Bylina L. Conceptual Design of an Urban Pocket Park Located in the Site of the Occurrence of a Nineteenth-Century Chapel Using Representatives of Local Xerothermic Vegetation. Environments. 2024; 11(11):252. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments11110252

Chicago/Turabian StyleKopeć, Weronika, Ewa Hanus-Fajerska, and Leszek Bylina. 2024. "Conceptual Design of an Urban Pocket Park Located in the Site of the Occurrence of a Nineteenth-Century Chapel Using Representatives of Local Xerothermic Vegetation" Environments 11, no. 11: 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments11110252

APA StyleKopeć, W., Hanus-Fajerska, E., & Bylina, L. (2024). Conceptual Design of an Urban Pocket Park Located in the Site of the Occurrence of a Nineteenth-Century Chapel Using Representatives of Local Xerothermic Vegetation. Environments, 11(11), 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments11110252