Development and Validation of the Adolescent Bystander Intervention Barrier Perception Scale in School Bullying

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- What are the structural dimensions of adolescent bystander intervention barriers in school bullying?

- (2)

- Does the developed scale demonstrate measurement invariance across different age groups of adolescents?

- (3)

- What is the relationship between bystander intervention barrier perceptions and theoretically related variables?

2. Method

2.1. Research Procedure

2.2. Qualitative Interview Study

2.2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2.2. Interview Data Analysis and Results

2.3. Initial Scale Development

- (1)

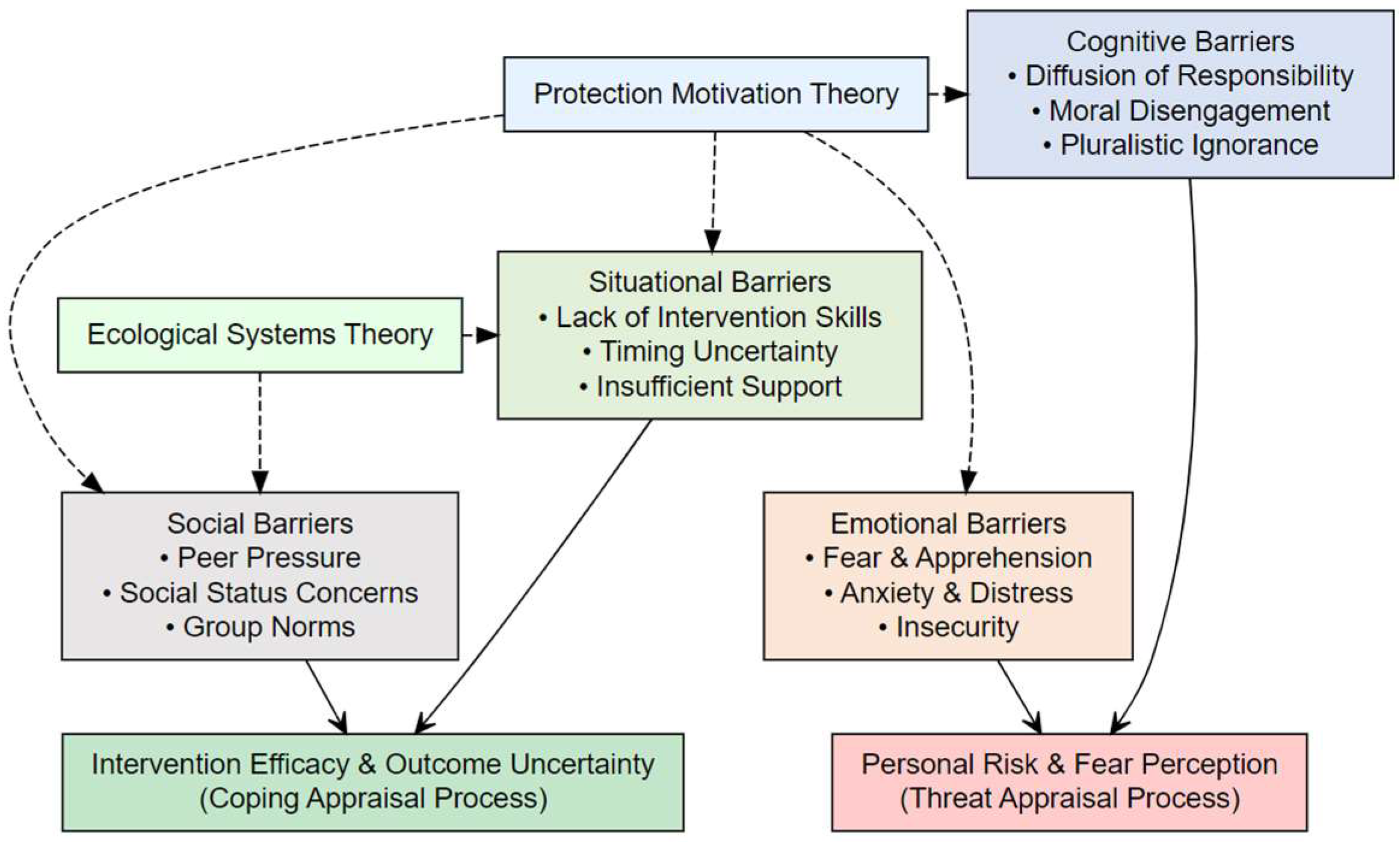

- Theme-to-theory mapping: We systematically mapped the six themes identified in interviews to core constructs in Protection Motivation Theory and Ecological Systems Theory. For example, “personal safety concerns” and “social evaluation worries” themes corresponded to the “threat appraisal” process in Protection Motivation Theory; “intervention efficacy doubts” and “situational uncertainty” themes corresponded to the “coping appraisal” process; “lack of support systems” and “culture-specific barriers” were explained through different levels of Ecological Systems Theory (microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem).

- (2)

- Item development: Based on the theoretical importance of each dimension and frequency mentioned in interviews, we preliminarily determined two core dimensions: “Personal Risk and Fear Perception” and “Intervention Efficacy and Outcome Uncertainty.” For each dimension, we planned to develop 12–15 items to ensure content coverage and space for subsequent selection. Item distribution covered all sub-themes.

- (3)

- Item writing: Specific items were written based on original interview expressions. For example, one student’s expression “I’m afraid that standing up to protect might make the bully more crazy” was transformed into the scale item “I worry that helping a bullied classmate might make the bully angrier and do worse things.”; another student’s mention of “I worry there’s no appropriate timing to protect others” was transformed into the scale item “I don’t know when is the best time to help.”

- (4)

- Expert review and revision: Three psychology professors and three psychology doctoral students participated in item evaluation as independent expert reviewers, none of whom were authors of this study, ensuring objectivity of the assessment. Evaluation content included item content representativeness, clarity of expression, age appropriateness, and theoretical relevance.

- (5)

- Cognitive interviews and language optimization: Participants in cognitive interviews were 10 students in the target age range (10–14 years), including 5 boys and 5 girls, all from schools different from the formal sample. These students had diversity in academic performance, family background, and socioeconomic status, ensuring item applicability to students from different backgrounds. Cognitive interviews employed the “think-aloud” technique, requiring students to verbally express their thinking process when answering each item, to assess item comprehensibility and the answering process.

2.4. Participants

2.5. Measures

2.5.1. Adolescent Bystander Intervention Barrier Perception Scale (Self-Developed)

2.5.2. Criterion-Related Variable Measurement Tools

- (1)

- (2)

- Positive Youth Development Scale (PYD-VSF). We used the very short form of the Positive Youth Development Scale Chinese version, revised by Huang et al. (2022), covering competence, confidence, character, caring, and connection. Dimension scores are the average of the items in each dimension, and the PYD total score is the average of all items, with higher scores indicating higher overall PYD levels. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale.

- (3)

- Intentional Self-Regulation Scale. We used the Intentional Self-Regulation Questionnaire developed by Gestsdóttir and Lerner (2007) and revised by W. Z. Dai et al. (2010). This questionnaire contains three dimensions: goal selection, goal optimization, and goal compensation, with a total of 9 items. It uses a 5-point scale (1 = “not at all like me,” 5 = “very much like me”), with higher total scores indicating better intentional self-regulation ability.

- (4)

- Self-Esteem Scale. Self-esteem was measured using the Chinese version of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965), with the Chinese version from the Commonly Used Psychological Assessment Manual (3rd edition) provided by X. Y. Dai et al. (2023). It consists of 10 items with a 4-point rating scale, with higher total scores indicating higher self-esteem levels.

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Item Analysis

3.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

3.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.3.1. Structural Validity

3.3.2. Criterion-Related Validity

3.4. Age Measurement Invariance of the Adolescent Bystander Intervention Barrier Perception Scale

3.5. Gender Measurement Invariance of the Adolescent Bystander Intervention Barrier Perception Scale

4. Discussion

4.1. Dimensional Structure and Theoretical Significance of Adolescent Bystander Intervention Barriers in School Bullying

4.2. Psychometric Properties and Application Value of the Adolescent Bystander Intervention Barrier Perception Scale

4.3. Relationships Between Adolescent Bystander Intervention Barrier Perceptions and Related Variables and Their Theoretical Implications

4.4. Theoretical Contributions and Practical Implications

4.4.1. Theoretical Contributions

- (1)

- By integrating Protection Motivation Theory and Ecological Systems Theory, this study offers a multi-level framework of bystander intervention barriers, moving beyond single-perspective models and capturing the complexity of bystander behavior (Salmivalli, 2014).

- (2)

- Empirical support for a two-factor structure—Personal Risk Perception and Efficacy Uncertainty—clarifies distinct yet interactive cognitive–affective processes underpinning bystander decisions, strengthening the psychological mechanism evidence base.

- (3)

- Mapping links between barrier perceptions and developmental indicators (e.g., positive youth development, self-regulation) extends theory connecting bystander behavior to adolescent development, aligning with calls to embed bullying intervention within a PYD framework (Espelage, 2014). This suggests moving beyond narrow skills training toward broader developmental promotion.

- (4)

- Establishing measurement invariance enables examination of developmental trajectories in intervention barriers and supports future longitudinal work.

4.4.2. Practical Implications

- (1)

- Multidimensional intervention strategies:

- (i)

- For Personal Risk and Fear Perception: establish safety-support systems; encourage collective (vs. solo) intervention; teach safe/indirect strategies and help-seeking.

- (ii)

- For Efficacy and Outcome Uncertainty: offer clear stepwise guidance on when/where/how to act; present successful cases to build confidence; use role-play to strengthen skills for uncertain situations.

- (2)

- Measurement invariance supports comparable assessment across ages and genders, enabling tailored, data-driven programming for different subgroups.

- (3)

- Integrative development approach: pair barrier reduction with resource building (e.g., self-esteem, social skills, moral education, self-regulation), consistent with PYD principles emphasizing holistic asset development (Lerner et al., 2005).

- (4)

- School ecological change: beyond individual-level training, modify the broader school ecology—clear anti-bullying norms, supportive peer culture, teacher intervention support, and a safe climate—consistent with social–ecological models (Swearer & Hymel, 2015).

- (5)

- Assessment-guided intervention: use the scale for needs assessment and iterative evaluation—pretest to identify barriers, mid-course monitoring to adjust strategies, and posttest to appraise effects—aligning with evidence-based psychosocial intervention standards (Durlak et al., 2011).

4.5. Research Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Grounded in Protection Motivation Theory and Ecological Systems Theory, this study is the first to develop a reliable and valid instrument from the perspective of perceived barriers, thereby shifting the research lens and providing a new theoretical framework and practical tool for bullying research. The measure establishes a two-factor structure comprising “Personal Risk and Fear Perception” and “Intervention Efficacy and Outcome Uncertainty.” Specifically, “Personal Risk and Fear Perception” corresponds to the threat appraisal process in Protection Motivation Theory, reflecting bystanders’ perception of personal safety threats and social costs that intervention might bring; “Intervention Efficacy and Outcome Uncertainty” corresponds to the coping appraisal process, reflecting bystanders’ judgment of the effectiveness of intervention behaviors and personal implementation capacity.

- (2)

- The scale demonstrates strong reliability, validity, and measurement invariance, offering an effective tool for assessing adolescents’ cognitions about bystander intervention barriers. At the practical level, the scale can be used to inform school-based bullying prevention efforts and practices that promote positive youth development. Specifically, educators can utilize this scale for needs assessment to identify the primary barrier types in student populations, thereby designing targeted intervention strategies: for students with high “Personal Risk and Fear Perception,” interventions can focus on establishing safety-support systems, encouraging collective intervention, and teaching indirect help-seeking strategies to reduce their perceived risk; for students with high “Intervention Efficacy and Outcome Uncertainty,” interventions can focus on providing clear intervention guidance, presenting successful cases, and conducting role-play training to enhance their intervention confidence. Furthermore, this scale can be used to track intervention effects and evaluate the effectiveness of anti-bullying programs, supporting evidence-based school practices.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W.H. Freeman and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, C. P., Cohen, J., Espelage, D. L., & Nation, M. (2021). Addressing school safety through comprehensive school climate approaches. School Psychology Review, 50(2–3), 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1994). Ecological models of human development. International Encyclopedia of Education, 3(2), 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bussey, K., Luo, A., Fitzpatrick, S., & Allison, K. (2020). Defending victims of cyberbullying: The role of self-efficacy and moral disengagement. Journal of School Psychology, 78, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(3), 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 9(2), 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, W. Z., Zhang, W., Li, D. P., Yu, C. F., & Wen, C. (2010). Stressful life events and adolescent problem behavior: The role of gratitude and intentional self-regulation. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 18(6), 796–798, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X. Y., Wang, M. C., & Liu, T. (2023). Handbook of commonly used psychological assessment scales (3rd ed.). Beijing Science and Technology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Darley, J. M., & Latané, B. (1968). Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8(4), 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSmet, A., Veldeman, C., Poels, K., Bastiaensens, S., Van Cleemput, K., Vandebosch, H., & De Bourdeaudhuij, I. (2016). Determinants of self-reported bystander behavior in cyberbullying incidents amongst adolescents. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17(4), 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doramajian, C., & Bukowski, W. M. (2015). A longitudinal study of the associations between moral disengagement and active defending versus passive bystanding during bullying situations. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 61(1), 144–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y. S., Kou, J. H., Wang, X. L., Xia, L. M., & Zou, R. H. (2006). Study on the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Psychological Science, 6, 1419–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., & Spinrad, T. L. (2006). Prosocial development. In N. Eisenberg, W. Damon, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development (pp. 646–718). John Wiley & Sons Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espelage, D. L. (2014). Ecological theory: Preventing youth bullying, aggression, and victimization. Theory Into Practice, 53(4), 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espelage, D. L., Green, H. D., & Polanin, J. R. (2012). Willingness to intervene in bullying episodes among middle school students: Individual and peer-group influences. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 32(6), 776–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrigar, L. R., Wegener, D. T., MacCallum, R. C., & Strahan, E. J. (1999). Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychological Methods, 4(3), 272–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gestsdóttir, S., & Lerner, R. M. (2007). Intentional self-regulation and positive youth development in early adolescence: Findings from the 4-h study of positive youth development. Developmental Psychology, 43(2), 508–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gestsdóttir, S., & Lerner, R. M. (2008). Positive development in adolescence: The development and role of intentional self-regulation. Human Development, 51(3), 202–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gini, G., Pozzoli, T., & Hauser, M. (2008). Bullies have enhanced moral competence to judge relative to victims, but lack moral compassion. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(5), 887–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, W. J. (2017). The effectiveness of policy interventions for school bullying: A systematic review. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 8(1), 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, D. L., Pepler, D. J., & Craig, W. M. (2001). Naturalistic observations of peer interventions in bullying. Social Development, 10(4), 512–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J. S., & Espelage, D. L. (2012). A review of research on bullying and peer victimization in school: An ecological system analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17(4), 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L. Y., Liang, K. X., Chen, S. Y., Kang, W., & Chi, X. L. (2022). Validity and reliability test of the Chinese version of the Very Short Form of the Positive Youth Development Scale. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 36(5), 445–450. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, L. N., & Nickerson, A. B. (2019). Bystander intervention in bullying: Role of social skills and gender. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 39(2), 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvonen, J., & Galván, A. (2008). Peer influence in involuntary social groups: Lessons from research on bullying. In M. J. Prinstein, & K. A. Dodge (Eds.), Understanding peer influence in children and adolescents (pp. 225–244). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, R. M., Lerner, J. V., Almerigi, J. B., Theokas, C., Phelps, E., Gestsdottir, S., Naudeau, S., Jelicic, H., Alberts, A., Ma, L., Smith, L. M., Bobek, D. L., Richman-Raphael, D., Simpson, I., Christiansen, E. D., & von Eye, A. (2005). Positive youth development, participation in community youth development programs, and community contributions of fifth-grade adolescents: Findings from the first wave of the 4-H study of positive youth development. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 25(1), 17–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Chen, P. Y., Chen, F. L., & Chen, Y. L. (2015). Preventing school bullying: Investigation of the link between anti-bullying strategies, prevention ownership, prevention climate, and prevention leadership. Applied Psychology, 66(4), 577–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z., Yang, Y., & Jiang, Y. (2025). The effect of adolescents’ ego-identity on problematic short video use in an online learning environment: The role of psychological resilience and academic procrastination. Youth & Society, 57, 1346–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellor, D., & Moore, K. A. (2014). The use of Likert scales with children. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 39(3), 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S., van Stralen, M. M., & West, R. (2011). The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, A. B., Aloe, A. M., Livingston, J. A., & Feeley, T. H. (2014). Measurement of the bystander intervention model for bullying and sexual harassment. Journal of Adolescence, 37(4), 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermann, M. L. (2011). Moral disengagement among bystanders to school bullying. Journal of School Violence, 10(3), 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olweus, D. (1994). Bullying at school: Basic facts and effects of a school based intervention program. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 35(7), 1171–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, S. B., Rutland, A., & Cameron, L. (2015). The development of bystander intentions and social-moral reasoning about intergroup verbal aggression. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 33(4), 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozzoli, T., & Gini, G. (2010). Active defending and passive bystanding behavior in bullying: The role of personal characteristics and perceived peer pressure. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(6), 815–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozzoli, T., & Gini, G. (2013). Why do bystanders of bullying help or not? A multidimensional model. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 33(3), 315–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzoli, T., Gini, G., & Vieno, A. (2012). The role of individual correlates and class norms in defending and passive bystanding behavior in bullying: A multilevel analysis. Child Development, 83(6), 1917–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, C. C., & Colman, A. M. (2000). Optimal number of response categories in rating scales: Reliability, validity, discriminating power, and respondent preferences. Acta Psychologica, 104(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigdon, E. E. (2012). Rethinking partial least squares path modeling: In praise of simple methods. Long Range Planning, 45(5–6), 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R. W. (1975). A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change. The Journal of Psychology, 91(1), 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmivalli, C. (2010). Bullying and the peer group: A review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15(2), 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmivalli, C. (2014). Participant roles in bullying: How can peer bystanders be utilized in interventions? Theory Into Practice, 53(4), 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmivalli, C., Lagerspetz, K., Björkqvist, K., Österman, K., & Kaukiainen, A. (1996). Bullying as a group process: Participant roles and their relations to social status within the group. Aggressive Behavior, 22(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmivalli, C., Voeten, M., & Poskiparta, E. (2011). Bystanders matter: Associations between reinforcing, defending, and the frequency of bullying behavior in classrooms. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 40(5), 668–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandstrom, M., Makover, H., & Bartini, M. (2013). Social context of bullying: Do misperceptions of group norms influence children’s responses to witnessed episodes? Social Influence, 8(2–3), 196–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R. (2008). Modeling health behavior change: How to predict and modify the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors. Applied Psychology, 57(1), 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjögren, B., Thornberg, R., & Hong, J. S. (2024). Moral disengagement and defender self-efficacy as predictors of bystander behaviors in peer victimization in middle school: A one-year longitudinal study. Journal of School Psychology, 107, 101400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swearer, S. M., & Hymel, S. (2015). Understanding the psychology of bullying: Moving toward a social-ecological diathesis-stress model. American Psychologist, 70(4), 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornberg, R., & Jungert, T. (2013). Bystander behavior in bullying situations: Basic moral sensitivity, moral disengagement and defender self-efficacy. Journal of Adolescence, 36(3), 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornberg, R., Tenenbaum, L., Varjas, K., Meyers, J., Jungert, T., & Vanegas, G. (2012). Bystander motivation in bullying incidents: To intervene or not to intervene? Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 13(3), 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | Factor Loading | Communality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Personal Risk and Fear | Intervention Efficacy and Outcome Uncertainty | ||

| I worry that helping bullied classmates might make the bullies angrier and do worse things. | 0.83 | 0.02 | 0.74 |

| I’m afraid that helping bullied classmates might make other students unwilling to play with me. | 0.82 | 0.16 | 0.79 |

| I’m a bit scared and prefer not to get involved in other people’s troubles. | 0.79 | 0.10 | 0.81 |

| I feel that if I help, it might make the situation worse. | 0.79 | 0.08 | 0.76 |

| I don’t know when would be the best time to offer help. | 0.07 | 0.85 | 0.74 |

| I worry that if I help, those bullies might bully others even more. | 0.02 | 0.83 | 0.75 |

| If no one supports me, I would feel lonely and unsure of what to do. | 0.05 | 0.79 | 0.78 |

| If I’m uncertain about what happened, I might not know whether I should help or not. | 0.11 | 0.79 | 0.7 |

| I worry that my help might be useless, or others might think I’m meddling in their business. | 0.10 | 0.78 | 0.78 |

| If the bullied classmate doesn’t want my help, I would feel confused and sad, not knowing what to do. | 0.11 | 0.76 | 0.79 |

| Internal Consistency Reliability | 0.90 | 0.94 | |

| x2 | df | RMSEA | CFI | TLI | SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Middle School (Sample 2) | 76.041 | 34 | 0.051 | 0.976 | 0.969 | 0.027 |

| Upper Elementary (Sample 3) | 110.296 | 34 | 0.064 | 0.965 | 0.954 | 0.027 |

| Items | Perceived Personal Risk and Fear | Intervention Efficacy and Outcome Uncertainty | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I worry that helping bullied classmates might make the bullies angrier and do worse things. | 0.75 | 0.81 | ||

| I’m afraid that helping bullied classmates might make other students unwilling to play with me. | 0.84 | 0.83 | ||

| I’m a bit scared and prefer not to get involved in other people’s troubles. | 0.89 | 0.86 | ||

| I feel that if I help, it might make the situation worse. | 0.88 | 0.89 | ||

| I don’t know when would be the best time to offer help. | 0.79 | 0.87 | ||

| I worry that if I help, those bullies might bully others even more. | 0.80 | 0.85 | ||

| If no one supports me, I would feel lonely and unsure of what to do. | 0.85 | 0.78 | ||

| If I’m uncertain about what happened, I might not know whether I should help or not. | 0.87 | 0.76 | ||

| I worry that my help might be useless, or others might think I’m meddling in their business. | 0.87 | 0.86 | ||

| If the bullied classmate doesn’t want my help, I would feel confused and sad, not knowing what to do. | 0.84 | 0.72 | ||

| CR | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.92 |

| AVE | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.65 |

| Criterion | Prosocial Behavior | PYD | Intentional Self-Regulation | Self-Esteem |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABIBP | −0.24 *** | −0.23 *** | −0.19 *** | −0.33 *** |

| Personal Risk and Fear Perception | −0.25 *** | −0.24 *** | −0.19 *** | −0.30 *** |

| Intervention Efficacy and Outcome Uncertainty | −0.23 *** | −0.22 *** | −0.19 *** | −0.35 *** |

| Model | x2 | df | c | RMSEA | CFI | TLI | SRMR | |ΔCFI| | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement invariance | configural | 185.99 | 68 | 1.94 | 0.058 | 0.970 | 0.961 | 0.027 | |

| metric | 213.35 | 76 | 1.84 | 0.060 | 0.965 | 0.959 | 0.038 | 0.005 | |

| scalar | 235.51 | 84 | 1.76 | 0.059 | 0.962 | 0.959 | 0.040 | 0.003 | |

| residual | 268.97 | 94 | 1.84 | 0.060 | 0.956 | 0.958 | 0.040 | 0.006 | |

| Structural invariance | variance | 275.68 | 96 | 1.81 | 0.06 | 0.955 | 0.958 | 0.043 | 0.001 |

| covariance | 303.67 | 97 | 1.82 | 0.065 | 0.948 | 0.952 | 0.047 | 0.007 | |

| latent | 334.16 | 99 | 1.80 | 0.068 | 0.941 | 0.946 | 0.086 | 0.007 |

| Model | x2 | df | c | RMSEA | CFI | TLI | SRMR | |ΔCFI| | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement invariance | configural | 185.338 | 68 | 1.749 | 0.058 | 0.970 | 0.961 | 0.025 | |

| metric | 198.963 | 76 | 1.660 | 0.056 | 0.969 | 0.963 | 0.027 | 0.001 | |

| scalar | 213.985 | 84 | 1.600 | 0.055 | 0.967 | 0.965 | 0.030 | 0.002 | |

| residual | 214.745 | 94 | 1.665 | 0.050 | 0.970 | 0.971 | 0.031 | 0.003 | |

| Structural invariance | variance | 219.128 | 96 | 1.643 | 0.050 | 0.969 | 0.971 | 0.033 | 0.001 |

| covariance | 218.026 | 97 | 1.651 | 0.049 | 0.969 | 0.972 | 0.033 | 0.000 | |

| latent | 240.395 | 99 | 1.639 | 0.053 | 0.964 | 0.968 | 0.073 | 0.005 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mao, Z.; Yang, Y. Development and Validation of the Adolescent Bystander Intervention Barrier Perception Scale in School Bullying. Behav. Sci. 2026, 16, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010055

Mao Z, Yang Y. Development and Validation of the Adolescent Bystander Intervention Barrier Perception Scale in School Bullying. Behavioral Sciences. 2026; 16(1):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010055

Chicago/Turabian StyleMao, Zheng, and Yisheng Yang. 2026. "Development and Validation of the Adolescent Bystander Intervention Barrier Perception Scale in School Bullying" Behavioral Sciences 16, no. 1: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010055

APA StyleMao, Z., & Yang, Y. (2026). Development and Validation of the Adolescent Bystander Intervention Barrier Perception Scale in School Bullying. Behavioral Sciences, 16(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010055