Resident-Led Peer Support Groups in Emergency Medicine: A Pilot Framework for Peer Leader Training

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EM | Emergency Medicine |

| EM/P | EM/Pediatrics |

| RSC | Resident Stress Checklist |

| Y1 | Year One |

| Y2 | Year Two |

| ACGME | Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education |

| PGY | Post-Graduate Year |

| NAMI | National Alliance on Mental Illness |

References

- Abrams, M. P. (2017). Improving resident well-being and burnout: The role of peer support. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 9(2), 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. (2023). ACGME data resource book: Academic year 2022–2023. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Available online: https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/publicationsbooks/2022-2023_acgme_databook_document.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- ACGME. (2025, January 22). Summary of proposed changes to ACGME common program requirements section VI. Available online: https://www.acgme.org/programs-and-institutions/programs/common-program-requirements/summary-of-proposed-changes-to-acgme-common-program-requirements-section-vi/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Calder-Sprackman, S., Kumar, T., Gerin-Lajoie, C., Kilvert, M., & Sampsel, K. (2018). Ice cream rounds: The adaptation, implementation, and evaluation of a peer-support wellness rounds in an emergency medicine resident training program. CJEM, 20(5), 777–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connors, J. N., Thornsberry, T., Hayden, J., Kroenke, K., Monahan, P. O., Draucker, C., Wasmuth, S., Kelker, H., Whitehead, A., & Welch, J. (2023). The use of peer support groups for emergency physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American College of Emergency Physicians Open, 4(1), e12897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haan, S., Lamprecht, H., Howlett, M. K., Fraser, J., Sohi, D., Adisesh, A., & Atkinson, P. R. (2018). A comparison of work stressors in higher and lower resourced emergency medicine health settings. CJEM, 20(5), 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doehring, M. C., Strachan, C. C., Haut, L., Crevier, K., Heniff, M., Crittendon, M., Connors, J. N., & Welch, J. L. (2023). Establishing a novel group-based litigation peer support program to promote wellness for physicians involved in medical malpractice lawsuits. Clinical Practice and Cases in Emergency Medicine, 7(4), 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grech, M. (2021). The effect of the educational environment on the rate of burnout among postgraduate medical trainees—A narrative literature review. Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development, 8, 23821205211018700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodkinson, A., Zhou, A., Johnson, J., Geraghty, K., Riley, R., Zhou, A., Panagopoulou, E., Chew-Graham, C. A., Peters, D., Esmail, A., & Panagioti, M. (2022). Associations of physician burnout with career engagement and quality of patient care: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ, 378, e070442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.-Y. (2012). Physicians’ needs in coping with emotional stressors: The case for peer support. Archives of Surgery, 147(3), 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, A., Tabatabai, R., Schreiber, J., Vo, A., & Riddell, J. (2022). “Everybody in this room can understand”: A qualitative exploration of peer support during residency training. AEM Education and Training, 6(2), e10728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J., & Chaudhari, A. (2023, June 27). Creating a peer support program [Broadcast]. Available online: https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/audio-player/18794745 (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Kimo Takayesu, J., Ramoska, E. A., Clark, T. R., Hansoti, B., Dougherty, J., Freeman, W., Weaver, K. R., Chang, Y., & Gross, E. (2014). Factors associated with burnout during emergency medicine residency. Academic Emergency Medicine: Official Journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, 21(9), 1031–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruczaj, K., Krawczyk, E., & Piegza, M. (2023). Medical malpractice stress syndrome in theory and practice—A narrative review. Medycyna Pracy, 74(6), 513–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacy, B. E., & Chan, J. L. (2018). Physician burnout: The hidden health care crisis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 16(3), 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G. S., Dizon, S. E., Feeney, C. D., Lee, Y.-L. A., Jordan, M., Galanos, A. N., & Trinh, J. V. (2023). Caring for each other: A resident-led peer debriefing skills workshop. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 15(2), 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichstein, P. M., He, J. K., Estok, D., Prather, J. C., Dyer, G. S., & Ponce, B. A. (2020). What is the prevalence of burnout, depression, and substance use among orthopaedic surgery residents and what are the risk factors? A collaborative orthopaedic educational research group survey study. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 478(8), 1709–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, Z. X., Yeo, K. A., Sharma, V. K., Leung, G. K., McIntyre, R. S., Guerrero, A., Lu, B., Sin Fai Lam, C. C., Tran, B. X., Nguyen, L. H., Ho, C. S., Tam, W. W., & Ho, R. C. (2019). Prevalence of burnout in medical and surgical residents: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(9), 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, B. A., Fowler, W. K., Thakkar, M., & Fahy, B. G. (2022). The BUDDYS system: A unique peer support strategy among anaesthesiology residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Turkish Journal of Anaesthesiology and Reanimation, 50(Suppl.1), S62–S67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K. A., O’Brien, B. C., & Thomas, L. R. (2020). “I wish they had asked”: A qualitative study of emotional distress and peer support during internship. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35(12), 3443–3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, H., Cobucci, R., Oliveira, A., Cabral, J. V., Medeiros, L., Gurgel, K., Souza, T., & Gonçalves, A. K. (2018). Burnout syndrome among medical residents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 13(11), e0206840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. The American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto, J. T., Lee, J., Lu, D. W., Sundaram, V., Bird, S. B., Blomkalns, A. L., & Alvarez, A. (2022). Factors driving burnout and professional fulfillment among emergency medicine residents: A national wellness survey by the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. AEM Education and Training, 6(S1), S5–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, J. (Director). (n.d.-a). AMA webinar: Peer support in the time of COVID-19 [Video recording]. Available online: https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/physician-health/using-power-peer-support-positively-impact-medicine (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Shapiro, J. (Director). (n.d.-b). Pioneering peer support programs: Full webcast [Video recording]. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GNZ7Huv3CB8 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Shapiro, J. (2024, October 15). Peer support programs for physicians: Mitigate the effects of emotional stressors through peer support. AMA STEPS Forward. Available online: https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/module/2767766?linkId=93545854 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Tavakol, M. (2019). Making sense of meta-analysis in medical education research. International Journal of Medical Education, 10, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vongsachang, H., & Jain, A. (2022). Virtual open house: Incorporating support persons into the residency community. The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 24(1), 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watling, C. J., & Lingard, L. (2012). Grounded theory in medical education research: AMEE guide No. 70. Medical Teacher, 34(10), 850–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webber, S., Schwartz, A., Kemper, K. J., Batra, M., Mahan, J. D., Babal, J. C., & Sklansky, D. J. (2021). Faculty and peer support during pediatric residency: Association with performance outcomes, race, and gender. Academic Pediatrics, 21(2), 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Peer Support Educational Method | Educational Materials and Content |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 1 + Year 2 | ||||||||||

| Leaders | Sessions Led | Sessions Led Average | Attrition | New Trained Leaders | Leaders | Sessions Led | Sessions Led Average | Total Leaders | Unique Leaders | Sessions Led | Sessions Led Average | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (min−max) | n (%) | n | n (%) | n (%) | n (min–max) | n | n | n (%) | n (min–max) | |

| Total | — | |||||||||||

| 6 | 20 | 3.3 | 4 | 10 | 12 | 26 | 2.2 | * | 16 | 46 | 2.9 (0–13) | |

| PGY | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0%) | 0 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0–0) | 0 | * | 0 (0%) | 0 (0–0) |

| 2 | 1 (17%) | 4 (20%) | 4 (4–4) | 0 (0%) | 7 | 7 (58%) | 19 (73%) | 2.7 (0–13) | 11 | 23 (50%) | 2.1 (0–13) | |

| 3–5 | 5 (83%) | 16 (80%) | 3.2 (2–4) | 4 (67%) | 3 | 5 (42%) | 7 (27%) | 1.0 (0–2) | 10 | 23 (50%) | 2.3 (0–4) | |

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Male | 3 (50%) | 10 (50%) | 3.3 (2–4) | 2 (50%) | 4 | 5 (42%) | 6 (23%) | 1.2 (0–2) | 8 | 7 | 16 (35%) | 2 (0–4) |

| Female | 3 (50%) | 10 (50%) | 3.3 (3–4) | 2 (50%) | 6 | 7 (58%) | 20 (77%) | 2.9 (0–13) | 10 | 9 | 30 (65%) | 3 (0–13) |

| URM | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 2 (33%) | 7 (35%) | (3–4) | 2 (50%) | 4 | 4 (33%) | 4 (15%) | 1.0 (0–2) | 6 | 6 | 11 (28%) | 1.8 (0–4) |

| No | 4 (67%) | 13 (65%) | (2–4) | 2 (50%) | 6 | 8 (67%) | 22 (85%) | 2.8 (0–13) | 12 | 10 | 35 (76%) | 2.9 (0–13) |

| Year 1 (Y1) (n = 13 Responses) | Year 2 (Y2) (n = 24 Responses) | |

|---|---|---|

| Peer Leader Post-Session Survey Question | Did you feel prepared or unprepared as the group leader? | I felt prepared to lead this peer support session. |

| Prepared/Yes | 13 (100%) | 24 (100%) |

| Unprepared/No | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

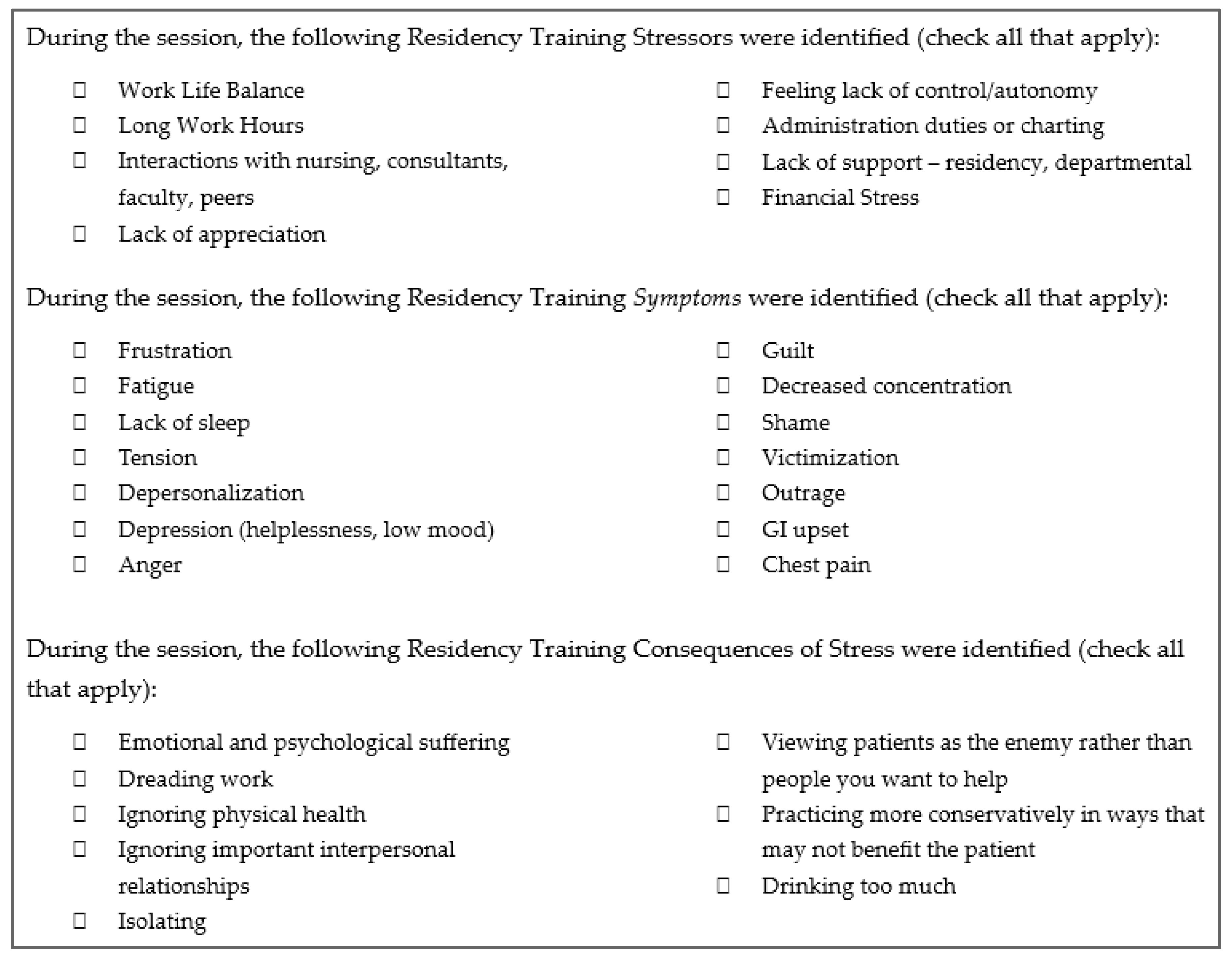

| Residency Training Stressor: “During the Session, the Following Residency Training Stressors Were Identified (Check All That Apply):” | |||

| Topic | Year 1 (Y1) (n = 18) n (%) | Year 2 (Y2) (n = 24) n (%) | Total Y1 + Y2 (n = 42) n (%) |

| Work Life Balance | 11 (61%) | 15 (63%) | 26 (62%) |

| Long Work Hours | 6 (33%) | 18 (75%) | 24 (57%) |

| Interactions with nursing, consultants, faculty, peers | 11 (61%) | 12 (50%) | 23 (55%) |

| Lack of appreciation | 5 (28%) | 5 (21%) | 10 (24%) |

| Feeling lack of control/autonomy | 4 (22%) | 5 (21%) | 9 (21%) |

| Administration duties or charting | 4 (22%) | 5 (21%) | 9 (21%) |

| Lack of support—residency, departmental | 5 (28%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (12%) |

| Financial Stress | 2 (11%) | 1 (4%) | 3 (7%) |

| Residency Symptoms of Stress: “During the session, the following Residency Training Symptoms of Stress were identified (check all that apply):” | |||

| Frustration | 14 (78%) | 18 (75%) | 32 (76%) |

| Fatigue | 12 (67%) | 18 (75%) | 30 (71%) |

| Lack of sleep | 7 (39%) | 13 (54%) | 20 (48%) |

| Tension | 7 (39%) | 8 (33%) | 15 (36%) |

| Depersonalization | 6 (33%) | 6 (25%) | 12 (29%) |

| Depression (helplessness, low mood) | 5 (28%) | 5 (21%) | 10 (24%) |

| Anger | 6 (33%) | 3 (13%) | 9 (21%) |

| Guilt | 5 (28%) | 2 (8%) | 7 (17%) |

| Decreased concentration | 3 (17%) | 2 (8%) | 5 (12%) |

| Shame | 3 (17%) | 1 (4%) | 4 (10%) |

| Victimization | 3 (17%) | 1 (4%) | 4 (10%) |

| Outrage | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| GI upset | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Chest pain | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Residency Consequences of Stress: “During the session, the following Residency Training Consequences of Stress were identified (check all that apply):” | |||

| Emotional and psychological suffering | 8 (44%) | 14 (58%) | 22 (52%) |

| Dreading work | 11 (61%) | 10 (42%) | 21 (50%) |

| Ignoring physical health | 9 (50%) | 8 (33%) | 17 (40%) |

| Ignoring important interpersonal relationships | 5 (28%) | 6 (25%) | 11 (26%) |

| Isolating | 4 (22%) | 4 (17%) | 8 (19%) |

| Viewing patients as the enemy rather than people you want to help | 3 (17%) | 2 (8%) | 5 (12%) |

| Practicing more conservatively in ways that may not benefit the patient | 3 (17%) | 1 (4%) | 4 (10%) |

| Drinking too much (alcohol) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Reed, K.D.; Weston, A.P.; Serpe, A.E.; Folk, D.D.; Destrampe, J.M.; Kelker, H.P.; Humbert, A.J.; Pettit, K.E.; Welch, J.L. Resident-Led Peer Support Groups in Emergency Medicine: A Pilot Framework for Peer Leader Training. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1744. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121744

Reed KD, Weston AP, Serpe AE, Folk DD, Destrampe JM, Kelker HP, Humbert AJ, Pettit KE, Welch JL. Resident-Led Peer Support Groups in Emergency Medicine: A Pilot Framework for Peer Leader Training. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1744. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121744

Chicago/Turabian StyleReed, Kyra D., Alexandria P. Weston, Alexandra E. Serpe, Destiny D. Folk, Jacob M. Destrampe, Heather P. Kelker, Aloysius J. Humbert, Katie E. Pettit, and Julie L. Welch. 2025. "Resident-Led Peer Support Groups in Emergency Medicine: A Pilot Framework for Peer Leader Training" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 12: 1744. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121744

APA StyleReed, K. D., Weston, A. P., Serpe, A. E., Folk, D. D., Destrampe, J. M., Kelker, H. P., Humbert, A. J., Pettit, K. E., & Welch, J. L. (2025). Resident-Led Peer Support Groups in Emergency Medicine: A Pilot Framework for Peer Leader Training. Behavioral Sciences, 15(12), 1744. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121744