Resilience, Life Satisfaction, and Well-Being in Portuguese Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Mental Health Continuum–Short Form

2.3.2. Escala de Avaliação do Eu Resiliente (Resilient Self-Assessment Scale, RSAS)

- (a)

- External supports or “I have” (four items that analyze external resources, e.g., “I have people around me I trust and who love me, no matter what”; α total scale = 0.82);

- (b)

- Inner strengths or “I am” (three items that assess internal personal strengths, e.g., “I am a person people can like and love”; α total scale = 0.73);

- (c)

- Social skills or “I can” (five items that encompass the interpersonal skills that allow individuals to discuss their concerns and find solutions to their problems, e.g., “I can talk to others about things that frighten me or bother me”; α total scale = 0.86); and

- (d)

- Willingness to act or “I am willing” (two items that assess the individual’s level of responsibility and self-confidence; α total scale = 0.69).

2.3.3. Multidimensional Life Satisfaction Scale for Adolescents (MLSSA)

- (a)

- Family: It measures satisfaction with the family environment and includes ten items that describe a healthy, harmonious, affectionate family environment with satisfying relationships (α total scale = 0.89).

- (b)

- Self: It measures satisfaction (nine items) with positive personal characteristics, such as self-esteem, sense of humor, ability to relate to others, ability to show affection, and overall enjoyment of life (α total scale = 0.91).

- (c)

- School: It measures satisfaction with the school environment (six items), including perceived importance of the school itself, the interpersonal relationships at school, and overall satisfaction with school (α total scale = 0.88).

- (d)

- Compared self: It assesses satisfaction based on social comparisons with their peers. The six items relate to topics such as leisure activities, friendships, and fulfilling desires and affections (α total scale = 0.93).

- (e)

- Nonviolence: It assesses the desire not to get involved in aggressive situations (six items), such as fights and arguments (α total scale = 0.80).

- (f)

- Self-efficacy: It measures (seven items) satisfaction with the ability and competence to achieve goals. The items in this dimension relate to autonomy, leisure, material satisfaction, and fulfilling desires (α total scale = 0.85).

- (g)

- Friendship: It assesses satisfaction with friendships (eight items), support received, and enjoyment (α total scale = 0.90).

2.3.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Resilience, Life Satisfaction and Well-Being Evaluation and Differences According to Educational Attainment

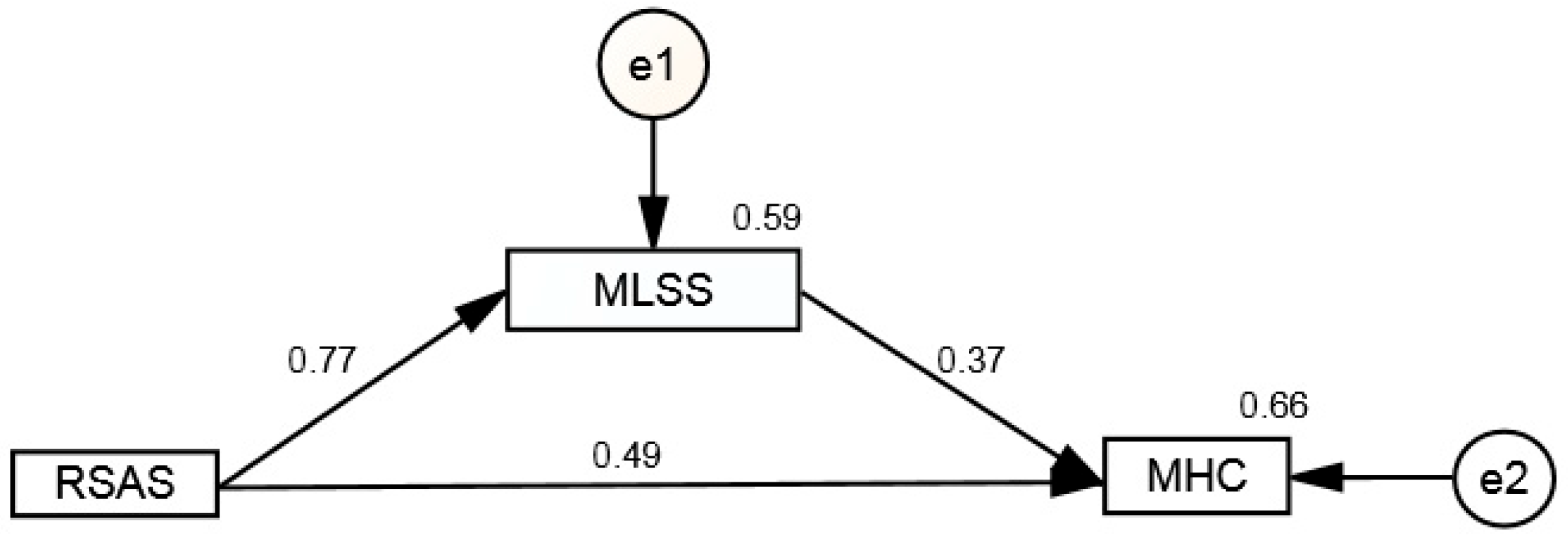

4.2. Variable Relations and Causal Model

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CCA | Canonical Correlation Analysis |

| CV | Coefficient of variation |

| HBSC | Health Behavior in School-aged Children |

| M | Mean |

| MA | Mediation analyses |

| Max. | Maximum |

| Md | Median |

| MH | Mental Health |

| MHC-SF | Mental Health Continuum–Short Form |

| Min. | Minimum |

| MLSSA | Multidimensional Life Satisfaction Scale for Adolescents |

| RSAS | Resilient Self-Assessment Scale |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SK | Skewness |

| WB | Well-being |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| WL | Wilks’ lambda |

References

- Arslan, G. (2021). School belongingness, well-being, and mental health among adolescents: Exploring the role of loneliness. Australian Journal of Psychology, 73(1), 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aymerich, M., Cladellas, R., Castelló, A., Casas, F., & Cunill, M. (2021). The evolution of life satisfaction throughout childhood and adolescence: Differences in young people’s evaluations according to age and gender. Child Indicators Research, 14(6), 2347–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azpiazu Izaguirre, L., Fernández, A. R., & Palacios, E. G. (2021). Adolescent life satisfaction explained by social support, emotion regulation, and resilience. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 694183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, M., Branquinho, C., Moraes, B., Cerqueira, A., Tomé, G., Noronha, C., Gaspar, T., Rodrigues, N., & Matos, M. G. d. (2024). Positive Youth development, mental stress and life satisfaction in middle school and high school students in Portugal: Outcomes on stress, anxiety and depression. Children, 11(6), 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaspar, T., Guedes, F., & Equipa Aventura Social. (2022). A saúde dos adolescentes PORTUGUESES em contexto de Pandemia–Dados nacionais do estudo HBSC 2022. Equipa Aventura Social. Available online: https://aventurasocial.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/HBSC_Relato%CC%81rioNacional_2022.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Goldbeck, L., Schmitz, T. G., Besier, T., Herschbach, P., & Henrich, G. (2007). Life satisfaction decreases during adolescence. Quality of Life Research, 16(6), 969–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haidt, J. (2024). A geração ansiosa. Como a grande reconfiguração da infância está a provocar uma epidemia de doença mental (4th ed.). D. Quixote. [Google Scholar]

- Iasiello, M., van Agteren, J., Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Lo, L., Fassnacht, D. B., & Westerhof, G. J. (2022). Assessing mental wellbeing using the Mental Health Continuum—Short Form: A systematic review and meta-analytic structural equation modelling. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 29(4), 442–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardim, J., & Pereira, A. (2006). Competências pessoais e sociais: Guia prático para a mudança positiva. Asa Editores. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes, C. L., Wissing, M., Potgieter, J. P., Temane, M., Kruger, A., & van Rooy, S. (2008). Evaluation of the mental health continuum-short form (MHC-SF) in Setswana-speaking South Africans. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 15(3), 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibovich, N., Schmid, V., & Calero, A. (2018). The Need to Belong (NB) in adolescence: Adaptation of a scale for its assessment. Psychology and Behavioral Science International Journal, 8(5), 555747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, L., Santos, J., & Loureiro, C. (2025). Mental health continuum—short form: Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) of competing models with adolescents from Portugal. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(4), 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marôco, J. (2021). Análise de equações estruturais: Fundamentos teóricos, software & aplicações. ReportNumber. [Google Scholar]

- Marquez, J., Francis-Hew, L., & Humphrey, N. (2023). Protective factors for resilience in adolescence: Analysis of a longitudinal dataset using the residuals approach. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 17(1), 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslak, M. A. (2022). Working adolescents: Rethinking education for and on the job. In Global perspectives on adolescence and education. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesman, E., Vreeker, A., & Hillegers, M. (2021). Resilience and mental health in children and adolescents: An update of the recent literature and future directions. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 34(6), 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Núñez-Regueiro, F., & Núñez-Regueiro, S. (2021). Identifying salient stressors of adolescence: A systematic review and content analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(12), 2533–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orban, E., Li, L. Y., Gilbert, M., Napp, A. K., Kaman, A., Topf, S., Boecker, M., Devine, J., Reiß, F., Wendel, F., Jung-Sievers, C., Ernst, V. S., Franze, M., Möhler, E., Breitinger, E., Bender, S., & Ravens-Sieberer, U. (2024). Mental health and quality of life in children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1275917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, Z., Moosajee, F., & Van Wyk, B. (2022). Measuring mental wellness of adolescents: A systematic review of instruments. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 835601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, Z., & van Wyk, B. (2022). Rethinking mental wellness among adolescents: An integrative review protocol of mental health components. Systematic Reviews, 11(1), 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Fernández, A., Ramos-Díaz, E., Fernández-Zabala, A., Goñi, E., Esnaola, I., & Goñi, A. (2016). Contextual and psychological variables in a descriptive model of subjective well-being and school engagement. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology: IJCHP, 16(2), 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J. C., Erse, M. P., Simões, R. P., Façanha, J. N., Marques, L. A., Matos, M. E., Loureiro, C. R., & Quaresma, M. H. (2021). Guia mais contigo educadores. Mais Contigo. Available online: http://eb23carlosteixeira.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Guia_Educadores_Contigo.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Segabinazi, J. D., Giacomoni, C. H., Dias, A. C. G., Teixeira, M. A. P., & Moraes, D. A. D. O. (2010). Desenvolvimento e validação preliminar de uma escala multidimensional de satisfação de vida para adolescentes. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 26, 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Usán, P., Salavera, C., Quílez-Robres, A., & Lozano-Blasco, R. (2022). Behaviour patterns between academic motivation, burnout and academic performance in primary school students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usán Supervía, P., Salavera Bordás, C., & Quílez Robres, A. (2022). The mediating role of self-esteem in the relationship between resilience and satisfaction with life in adolescent students. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 15, 1121–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivas-Fernandez, M., Garcia-Lopez, L.-J., Muela-Martinez, J. A., Piqueras, J. A., Espinosa-Fernandez, L., Jimenez-Vazquez, D., & del Mar Diaz-Castela, M. (2024). Exploring the role of resilience as a mediator in selective preventive transdiagnostic intervention (PROCARE+) for adolescents at risk of emotional disorders. European Journal of Psychology Open, 83, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willroth, E. C., Atherton, O. E., & Robins, R. W. (2021). Life satisfaction trajectories during adolescence and the transition to young adulthood: Findings from a longitudinal study of Mexican-origin youth. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 120(1), 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. (2018a). Guidelines on mental health promotive and preventive interventions for adolescents: Helping adolescents thrive. Available online: https://iris.who.int/server/api/core/bitstreams/1cba1d3a-29b6-407e-9b3e-250753af02ae/content (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- World Health Organization. (2018b). Strategy and plan of action on adolescent and youth health: Final report. Available online: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/51633 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- World Health Organization. (2022). World mental health report 2022: Transforming mental health for all. Geneva. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240049338 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- World Health Organization. (2025). Mental health of adolescents. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Xu, Y., Qi, K., Meng, S., Dong, X., Wang, S., Chen, D., & Chen, A. (2025). The effect of physical activity on resilience of Chinese children: The chain mediating effect of executive function and emotional regulation. BMC Pediatrics, 25(1), 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z., Sang, B., Liu, J., Zhao, Y., & Liu, Y. (2025). Associations between emotional resilience and mental health among chinese adolescents in the school context: The mediating role of positive emotions. Behavioral Sciences, 15(5), 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scales | Min. | Max. | M | SD | Md | CV | SK | Ku |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| External supports | 8.00 | 24.00 | 17.58 | 2.42 | 18.00 | 0.14 | −1.15 | 1.59 |

| Inner strengths | 4.00 | 18.00 | 13.24 | 1.72 | 14.00 | 0.13 | −1.20 | 2.45 |

| Willingness to act | 3.00 | 12.00 | 8.23 | 1.38 | 8.00 | 0.17 | −0.67 | 0.26 |

| Social skills | 6.00 | 30.00 | 20.20 | 3.74 | 21.00 | 0.18 | −0.81 | 0.82 |

| Total of RSAS | 23.00 | 84.00 | 59.12 | 7.99 | 61.00 | 0.14 | −0.98 | 1.79 |

| Emotional well-being | 0.00 | 5.00 | 3.95 | 0.93 | 4.00 | 0.23 | 1.30 | 165 |

| Social well-being | 0.00 | 5.00 | 3.25 | 1.22 | 3.60 | 0.38 | −0.73 | −0.40 |

| Psychological well-being | 0.17 | 5.00 | 3.71 | 1.01 | 4.00 | 0.27 | −1.13 | 1.08 |

| Total of MHC-SF | 0.29 | 5.00 | 3.60 | 0.99 | 3.86 | 0.27 | −0.93 | 0.39 |

| Family | 10.00 | 50.00 | 43.58 | 7.25 | 46.00 | 0.17 | −1.55 | 2.34 |

| Self | 9.00 | 45.00 | 34.49 | 7.58 | 36.00 | 0.22 | −0.85 | 0.22 |

| School | 6.00 | 30.00 | 22.74 | 4.68 | 23.00 | 0.21 | −0.68 | 0.44 |

| Compared Self | 6.00 | 30.00 | 20.57 | 5.30 | 20.00 | 0.26 | −0.16 | −0.50 |

| Non-violence | 11.00 | 30.00 | 23.19 | 3.89 | 23.00 | 0.17 | −0.48 | 0.03 |

| Self-efficacy | 7.00 | 35.00 | 25.93 | 4.42 | 26.00 | 0.17 | −0.66 | 0.92 |

| Friendship | 10.00 | 40.00 | 34.01 | 4.81 | 35.00 | 0.14 | −1.45 | 3.13 |

| Total of MLSSA | 78.00 | 258.00 | 205.34 | 29.15 | 205.39 | 0.14 | −0.87 | 0.80 |

| Total Scores | 5th–6th Grades | 7th–9th Grades | 10th–12th Grades | F | η2 | Post Hoc Tests § | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ab | ac | bc | |||

| MHC-SF | 4.15 a | 0.74 | 3.57 b | 0.98 | 3.20 c | 0.97 | 38.685 *** | 0.12 | * | * | * |

| RSAS | 61.63 a | 6.60 | 58.74 b | 8.55 | 57.68 c | 7.66 | 10.287 *** | 0.03 | * | * | ns |

| MLSSA | 219.25 a | 22.95 | 203.28 b | 29.46 | 197.86 c | 29.45 | 20.174 *** | 0.08 | * | * | ns |

| Canonical Function | r | Eigenvalue | WL | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.873 | 3.190 | 0.190 | 24.193 | 0.000 |

| 2 | 0.374 | 0.163 | 0.796 | 4.082 | 0.000 |

| 3 | 0.224 | 0.053 | 0.926 | 2.277 | 0.003 |

| 4 | 0.158 | 0.025 | 0.975 | 1.699 | 0.107 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Set A | ||||

| Emotional well-being | −0.806 | −0.052 | 0.082 | −0.273 |

| Social well-being | −0.811 | 0.053 | −0.192 | −0.283 |

| Psychological well-being | −0.897 | −0.033 | 0.160 | −0.210 |

| Family | −0.806 | 0.276 | 0.197 | 0.293 |

| Self | −0.874 | −0.278 | −0.101 | 0.062 |

| School | −0.726 | 0.157 | −0.170 | −0.045 |

| Compared Self | −0.472 | 0.098 | 0.185 | 0.376 |

| Non-violence | −0.570 | −0.397 | −0.189 | 0.435 |

| Self-efficacy | −0.829 | −0.147 | 0.115 | −0.223 |

| Friendship | −0.794 | 0.281 | −0.364 | 0.063 |

| Set B | −0.800 | 0.584 | 0.019 | −0.134 |

| External supports | −0.832 | 0.154 | −0.274 | 0.456 |

| Inner strengths | −0.832 | −0.336 | −0.324 | −0.300 |

| Willingness to act | −0.915 | −0.151 | 0.372 | 0.053 |

| Social skills | −0.800 | 0.584 | 0.019 | −0.134 |

| Canonical Variable | Set A by Self | Set A by Set B | Set B by Self | Set B by Set A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.592 | 0.450 | 0.715 | 0.545 |

| 2 | 0.045 | 0.006 | 0.125 | 0.018 |

| 3 | 0.036 | 0.002 | 0.080 | 0.004 |

| 4 | 0.067 | 0.002 | 0.080 | 0.002 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Loureiro, L.; Loureiro, C.; Santos, J. Resilience, Life Satisfaction, and Well-Being in Portuguese Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1743. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121743

Loureiro L, Loureiro C, Santos J. Resilience, Life Satisfaction, and Well-Being in Portuguese Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1743. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121743

Chicago/Turabian StyleLoureiro, Luís, Cândida Loureiro, and José Santos. 2025. "Resilience, Life Satisfaction, and Well-Being in Portuguese Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 12: 1743. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121743

APA StyleLoureiro, L., Loureiro, C., & Santos, J. (2025). Resilience, Life Satisfaction, and Well-Being in Portuguese Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study. Behavioral Sciences, 15(12), 1743. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121743