Relationship Between Food Selectivity, Adaptive Functioning and Behavioral Profile in Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Enrollment of Participants

2.2. Clinical Data

2.2.1. Cognitive Skills

2.2.2. Adaptive Functioning

2.2.3. ASD Symptoms Severity

2.2.4. Behavioral Profile

2.2.5. Food Selectivity

2.3. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Demographical and Food Selectivity Profiles

3.2. Participants’ Clinical Symptoms, Adaptive Skills, and Behavioral Profile

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2000). Manual for ASEBA preschool forms and profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Bandini, L. G., Anderson, S. E., Curtin, C., Cermak, S., Evans, E. W., Scampini, R., Maslin, M., & Must, A. (2010). Food selectivity in children with autism spectrum disorders and typically developing children. The Journal of Pediatrics, 157(2), 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buie, T., Campbell, D. B., Fuchs, G. J., Furuta, G. T., Levy, J., Vandewater, J., Whitaker, A. H., Atkins, D., Bauman, M. L., Beaudet, A. L., Carr, E. G., Gershon, M. D., Hyman, S. L., Jirapinyo, P., Jyonouchi, H., Kooros, K., Kushak, R., Levitt, P., Levy, S. E., … Winter, H. (2010). Evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment of gastrointestinal disorders in individuals with ASDs: A consensus report. Pediatrics, 125(1), S1–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, N., Wu, K., & Zhang, Y. (2022). Relationships between autistic traits, taste preference, taste perception, and eating behaviour. European Eating Disorders Review, 30(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtin, C., Hubbard, K., Anderson, S. E., Mick, E., & Must, A. (2015). Food selectivity, mealtime behaviour problems, spousal stress, and family food choices in children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(10), 3308–3315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominick, K. C., Davis, N. O., Lainhart, J., Tager-Flusberg, H., & Folstein, S. (2007). Atypical behaviours in children with autism and children with a history of language impairment. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 28(2), 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esler, A. N., Bal, V. H., Guthrie, W., Wetherby, A., Weismer, S. E., & Lord, C. (2015). The autism diagnostic observation schedule, toddler module: Standardized severity scores. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(9), 2704–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, M., Marano, M., & Testa, V. (2023). Food selectivity in children with autism: Guidelines for assessment and clinical intervention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6), 5092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, R., Iovino, L., Ricci, L., Avallone, A., Latina, R., & Ricci, P. (2025). Food selectivity and autism: A systematic review. World Journal of Clinical Pediatrics, 14(3), 101974. Available online: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v14/i3/101974.htm (accessed on October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Frigerio, A., Cattaneo, C., & Nobile, M. (2006). La valutazione dei problemi emotivo-comportamentali in un campione italiano di bambini in età prescolare attraverso la CBCL. Infanzia e Adolescenza, 5(2), 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Gesundheit, B., Rosenzweig, J. P., Naor, D., Lerer, B., Zachor, D. A., Procházka, V., Melamed, M., Kristt, D. A., Steinberg, A., Shulman, C., Hwang, P., Koren, G., Walfisch, A., Passweg, J. R., Snowden, J. A., Tamouza, R., Leboyer, M., Farge-Bancel, D., & Ashwood, P. (2013). Immunological and autoimmune considerations of Autism Spectrum Disorders. Journal of Autoimmunity, 44, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotham, K., Pickles, A., & Lord, C. (2009). Standardizing ADOS scores for a measure of severity in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39(5), 693–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, E. S., Stroud, L., Bloomfield, S., & Cronje, J. (2016). Griffiths scales of child development: Part 1 manual: Overview, development and psychometric properties (3rd ed.). Hogrefe. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, H., Fealko, C., & Soares, N. (2019). Autism spectrum disorder: Definition, epidemiology, causes, and clinical evaluation. Translational Pediatrics, 8(5), 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hus, V., Gotham, K., & Lord, C. (2014). Standardizing ADOS domain scores: Separating severity of social affect and restricted and repetitive behaviours. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(10), 2400–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, S. H., Voigt, R. G., Katusic, S. K., Weaver, A. L., & Barbaresi, W. J. (2009). Incidence of gastrointestinal symptoms in children: A population-based study. Pediatrics, 124(2), 680–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledford, J. R., & Gast, D. L. (2006). Feeding problems in children with autism spectrum disorder: A review. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 21(3), 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, E. A., Legere, C. H., Philip, N. S., Dickstein, D. P., & Radoeva, P. D. (2025). Relationship between food selectivity and mood problems in youth with a reported diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Biological Psychiatry Global Open Science, 5(4), 100481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lord, C., Rutter, M., DiLavore, P. C., Risi, S., Gotham, K., & Bishop, S. (2012). Autism diagnostic observation schedule, second edition (ADOS-2). Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Margari, L., Marzulli, L., Gabellone, A., & de Giambattista, C. (2020). Eating and mealtime behaviours in patients with autism spectrum disorder: Current perspectives. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 16, 2083–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mirizzi, P., Esposito, M., Ricciardi, O., Bove, D., Fadda, R., Caffò, A. O., Mazza, M., & Valenti, M. (2025). Food selectivity in children with autism spectrum disorder and in typically developing peers: Sensory processing, parental practices, and gastrointestinal symptoms. Nutrients, 17, 2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadon, G., Feldman, D. E., Dunn, W., & Gisel, E. (2011). Mealtime problems in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and their typically developing siblings: A comparison study. Autism, 15(1), 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakland, T. (2011). Adaptive behaviour assessment system (J. S. Kreutzer, J. DeLuca, & B. Caplan, Eds.; 2nd ed.). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Postorino, V., Sanges, V., Giovagnoli, G., Fatta, L. M., De Peppo, L., Armando, M., Vicari, S., & Mazzone, L. (2015). Clinical differences in children with autism spectrum disorder with and without food selectivity. Appetite, 92, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapin, I., & Tuchman, R. F. (2008). Autism: Definition, neurobiology, screening, diagnosis. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 55(5), 1129–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roid, G. H., & Miller, L. J. (1997). Leiter international performance scale–revised. Stoelting. [Google Scholar]

- Rossignol, D. A., & Frye, R. E. (2011). Melatonin in autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 53(9), 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, L., Heiss, C. J., & Campbell, E. E. (2008). A comparison of nutrient intake and eating behaviours of boys with and without autism. Topics in Clinical Nutrition, 23(1), 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, M. A., Nelson, N. W., & Curtis, A. B. (2014). Longitudinal follow-up of factors associated with food selectivity in children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism, 18(8), 924–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuchman, R., & Rapin, I. (2002). Epilepsy in autism. The Lancet Neurology, 1(6), 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wechsler, D. (2002). Wechsler preschool and primary scale of intelligence–third edition (WPPSI-III). The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzell, M. L., Pulver, S. L., McMahon, M. X. H., Rubio, E. K., Gillespie, S., Berry, R. C., Betancourt, I., Minter, B., Schneider, O., Yarasani, C., Rogers, D., Scahill, L., Volkert, V., & Sharp, W. G. (2024). Clinical correlates and prevalence of food selectivity in children with autism spectrum disorder. The Journal of Pediatrics, 269, 114004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

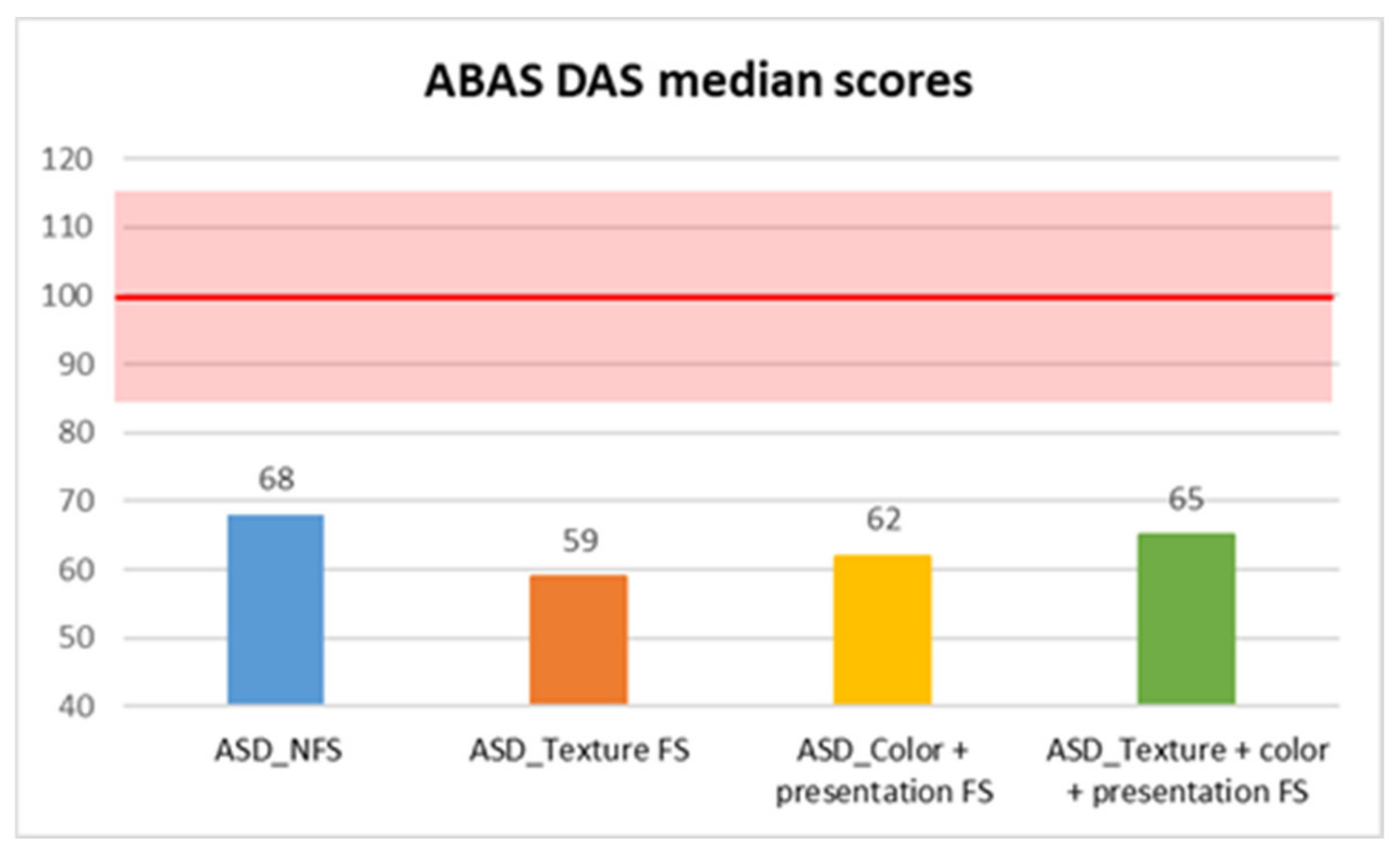

| ABAS DAS | ASD_NFS | Median | 68.00 |

| Standard Deviation | 13.834 | ||

| ASD_FS | |||

| Texture FS | Median | 59.00 | |

| Standard deviation | 14.479 | ||

| Color + presentation FS | Median | 62.00 | |

| Standard deviation | 17.428 | ||

| Texture + color + presentation FS | Median | 65.00 | |

| Standard deviation | 11.222 | ||

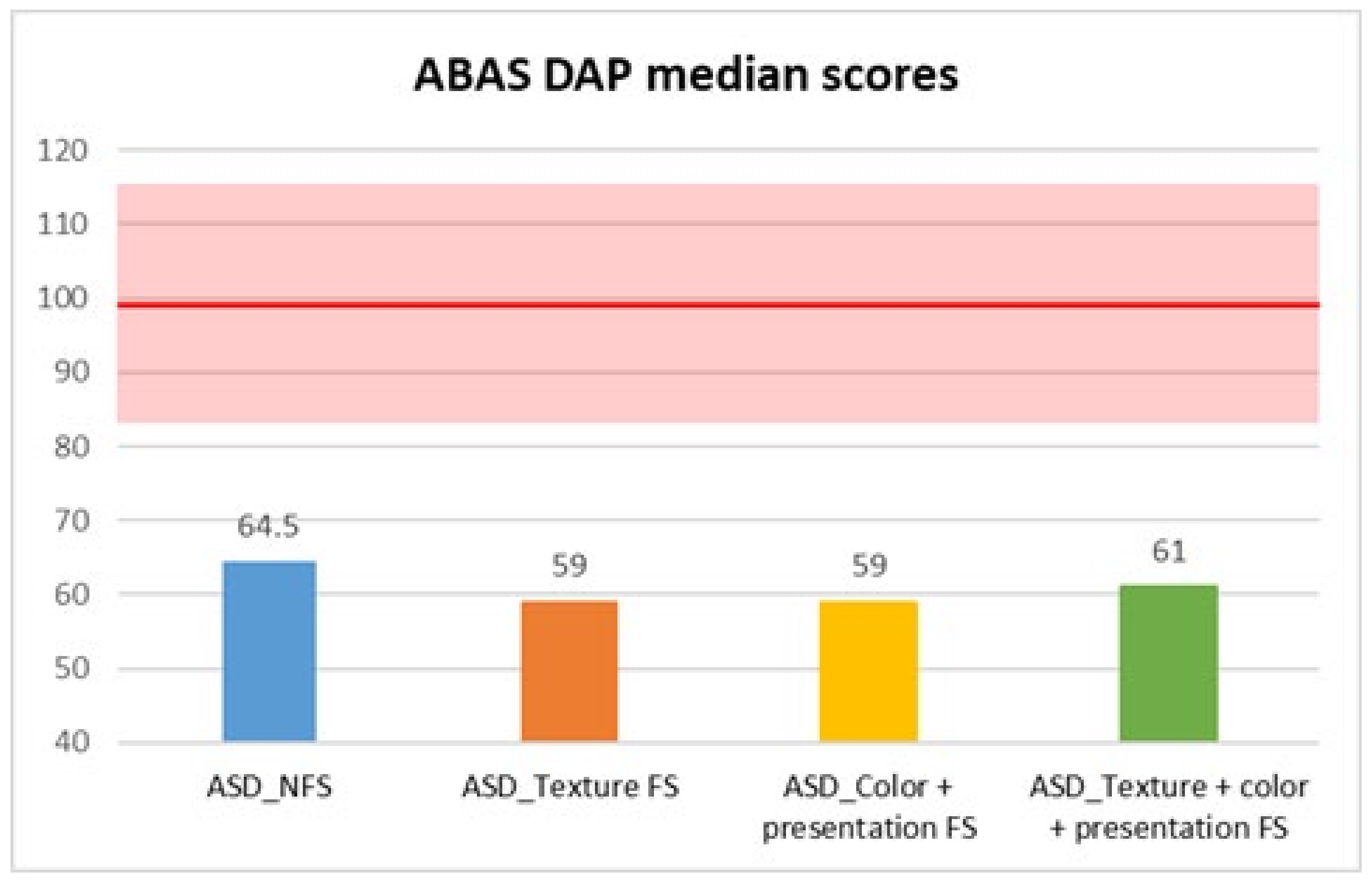

| ABAS DAP | ASD_NFS | Median | 64.50 |

| Standard deviation | 16.179 | ||

| ASD_FS | |||

| Texture FS | Median | 59.00 | |

| Standard deviation | 14.881 | ||

| Color + presentation FS | Median | 59.00 | |

| Standard deviation | 16.793 | ||

| Texture + color + presentation FS | Median | 61.00 | |

| Standard deviation | 10.116 | ||

| Subscale | FS (Median) | NFS (Median) | U | Z | p-Value | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

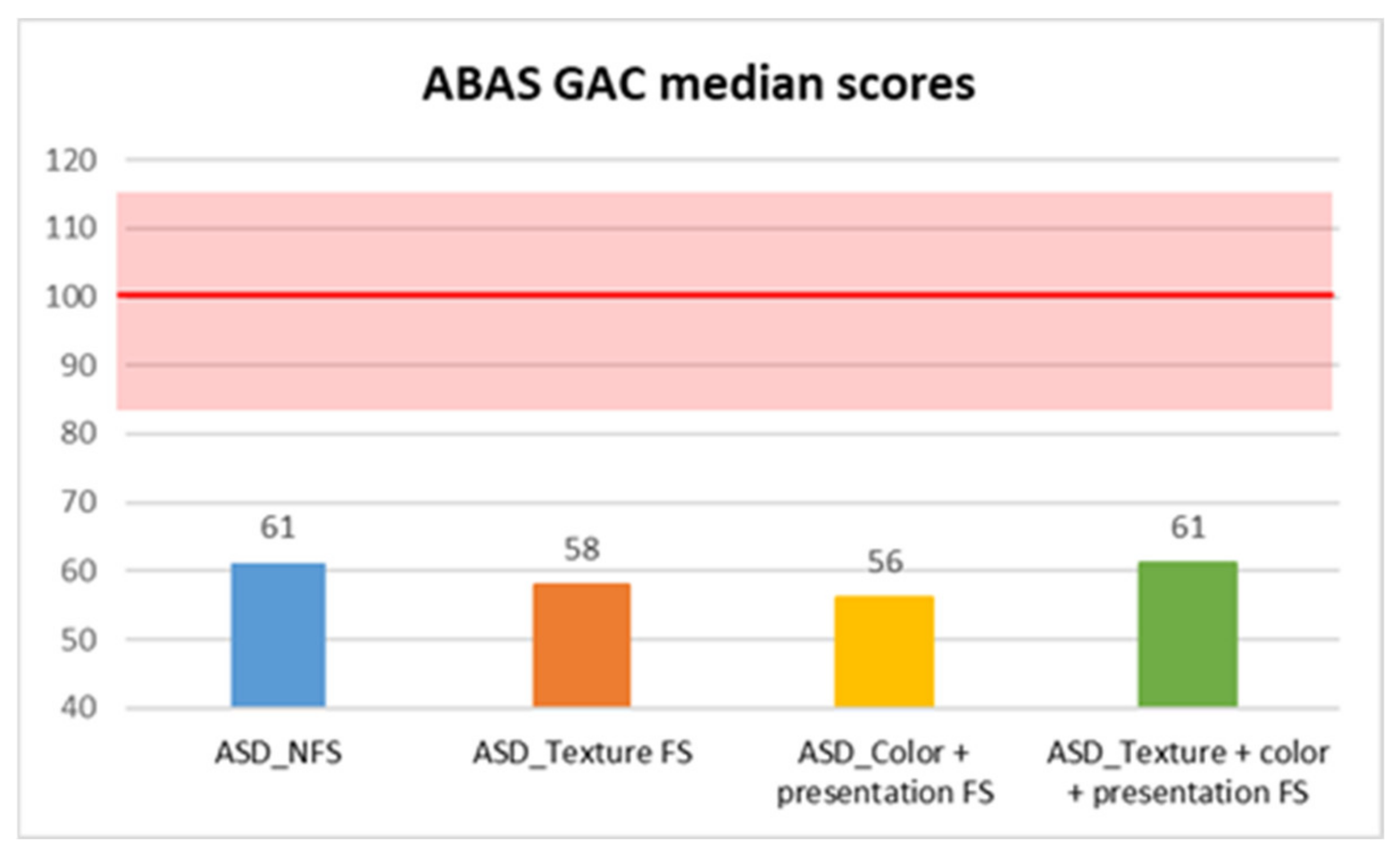

| GAC | 61 | 57 | 8070.5 | −2.85 | 0.004 ** | 0.17 |

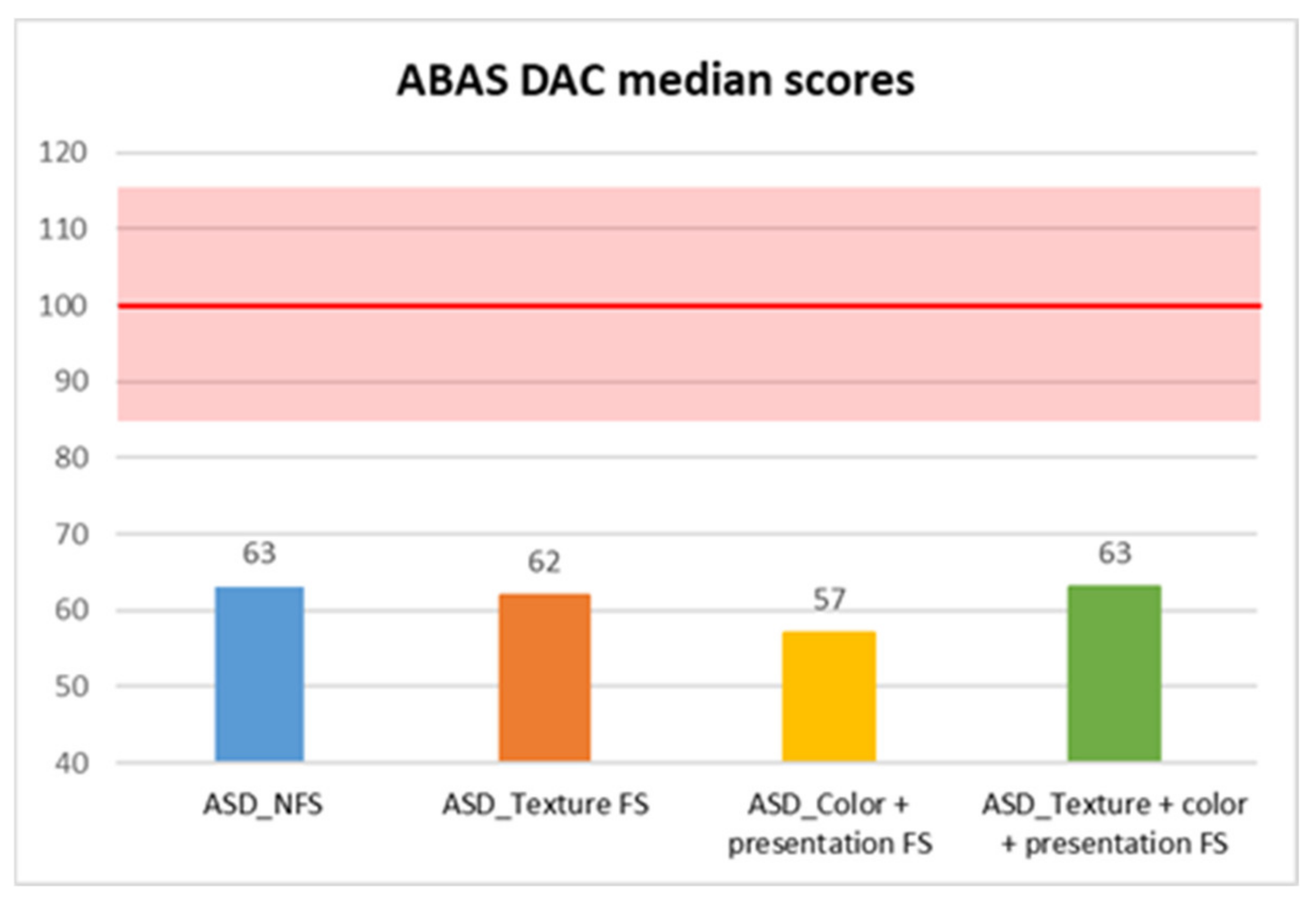

| DAC | 63 | 61 | 8634.5 | −2.04 | 0.042 * | 0.12 |

| DAS | 68 | 62 | 7942.5 | −3.04 | 0.002 ** | 0.18 |

| DAP | 64.5 | 59 | 7566.0 | −3.58 | <0.001 *** | 0.21 |

| Subscale | χ2 | df | p-Value | Post Hoc Pairwise Comparisons | Post Hoc p-Value | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAC | 5.343 | 3 | 0.148 | — | ||

| DAC | 1.123 | 3 | 0.772 | — | ||

| DAS | 8.265 | 3 | 0.041 | Color + Presentation FS vs. NFS | 0.004 ** | 0.480 |

| DAP | 10.770 | 3 | 0.013 | Color + Presentation FS vs. NFS | 0.002 ** | 0.566 |

| All_FS vs. NFS | 0.020 ** | 0.319 |

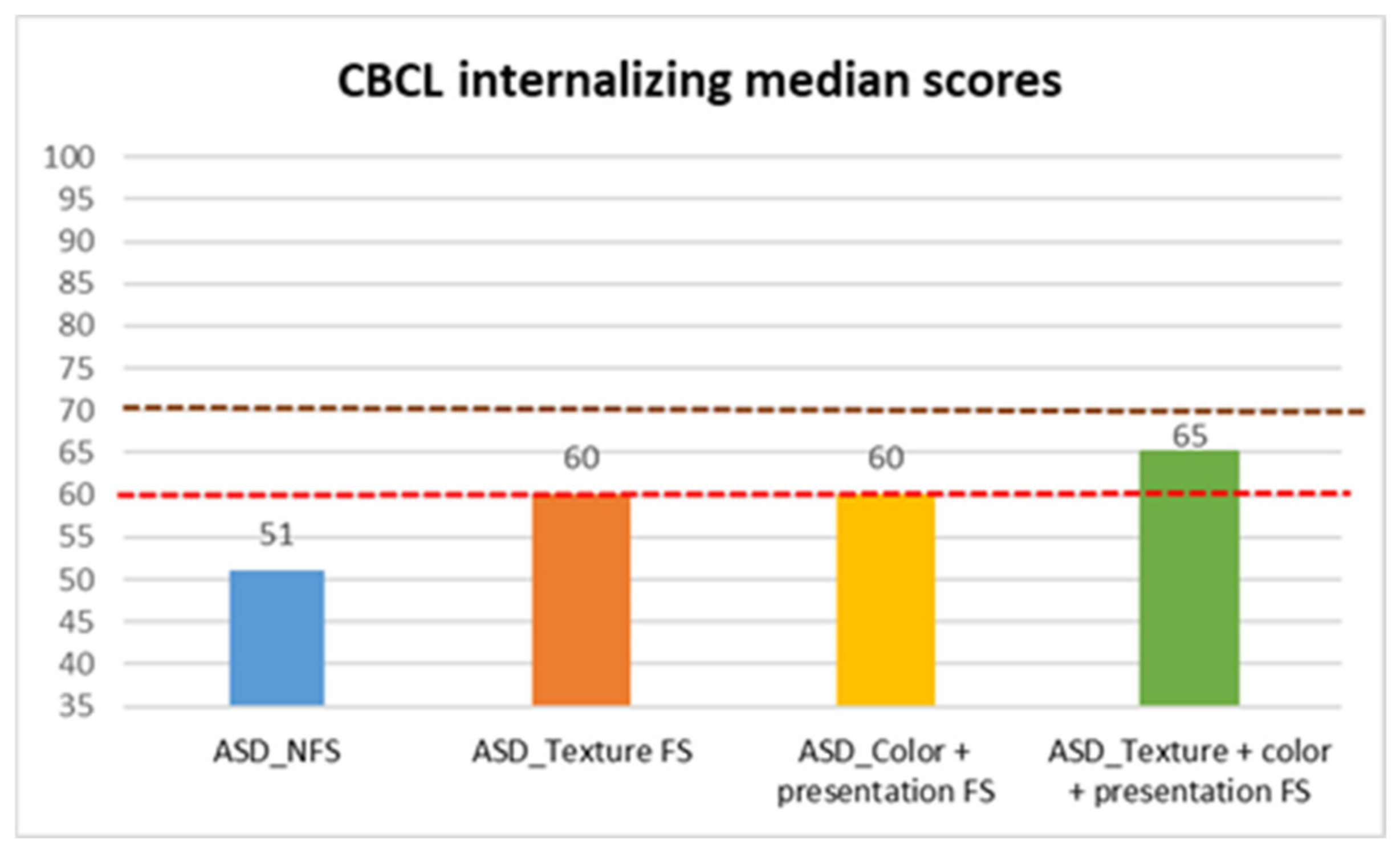

| CBCL internalizing | ASD_NFS | Median | 51.00 |

| Standard Deviation | 9.879 | ||

| ASD_FS | |||

| Texture FS | Median | 60.00 | |

| Standard deviation | 9.464 | ||

| Color + presentation FS | Median | 60.00 | |

| Standard deviation | 9.869 | ||

| Texture + color + presentation FS | Median | 65.00 | |

| Standard deviation | 7.369 | ||

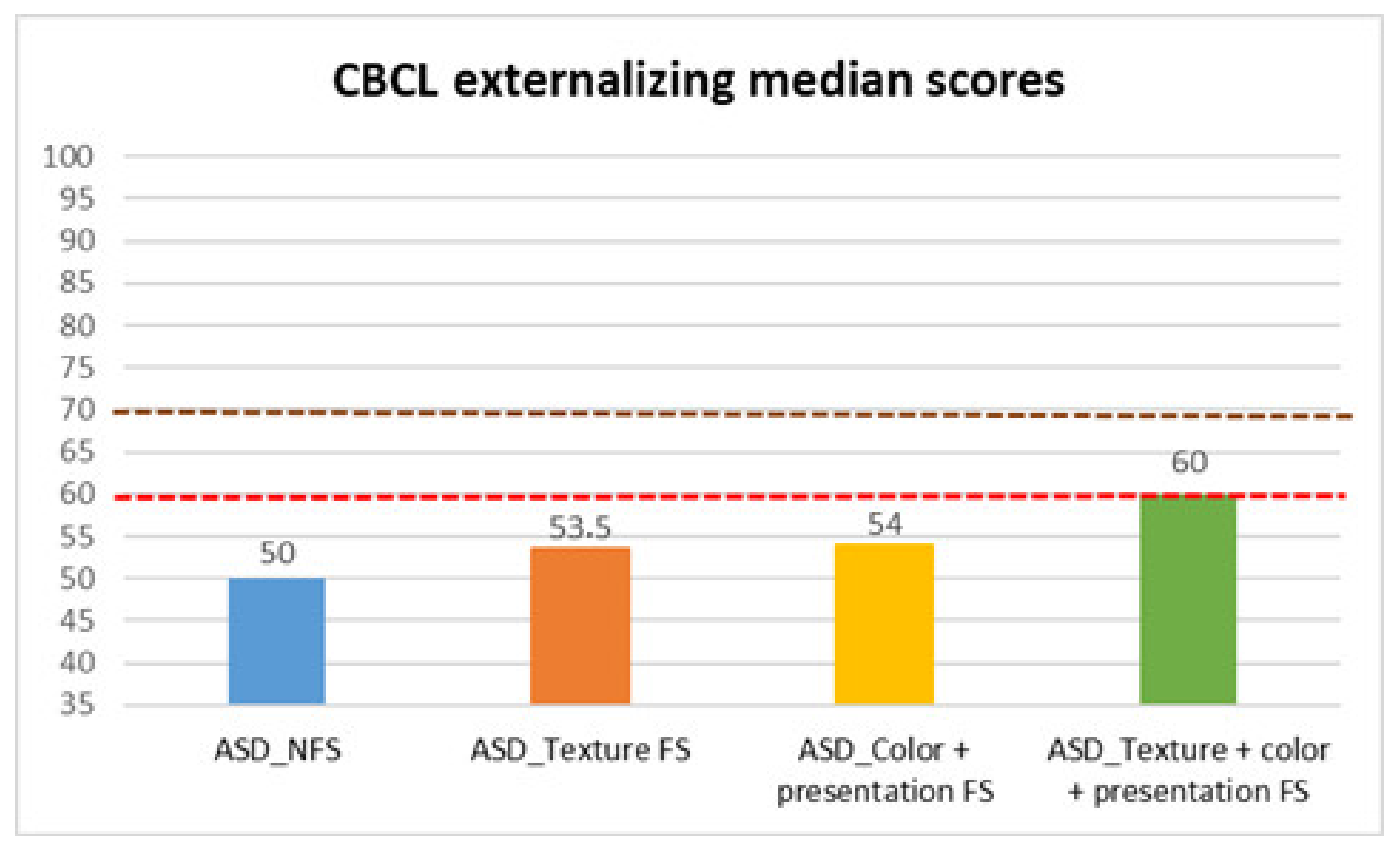

| CBCL externalizing | ASD_NFS | Median | 50.00 |

| Standard deviation | 9.109 | ||

| ASD_FS | |||

| Texture FS | Median | 53.50 | |

| Standard deviation | 8.706 | ||

| Color + presentation FS | Median | 54.00 | |

| Standard deviation | 7.829 | ||

| Texture + color + presentation FS | Median | 60.00 | |

| Standard deviation | 8.469 | ||

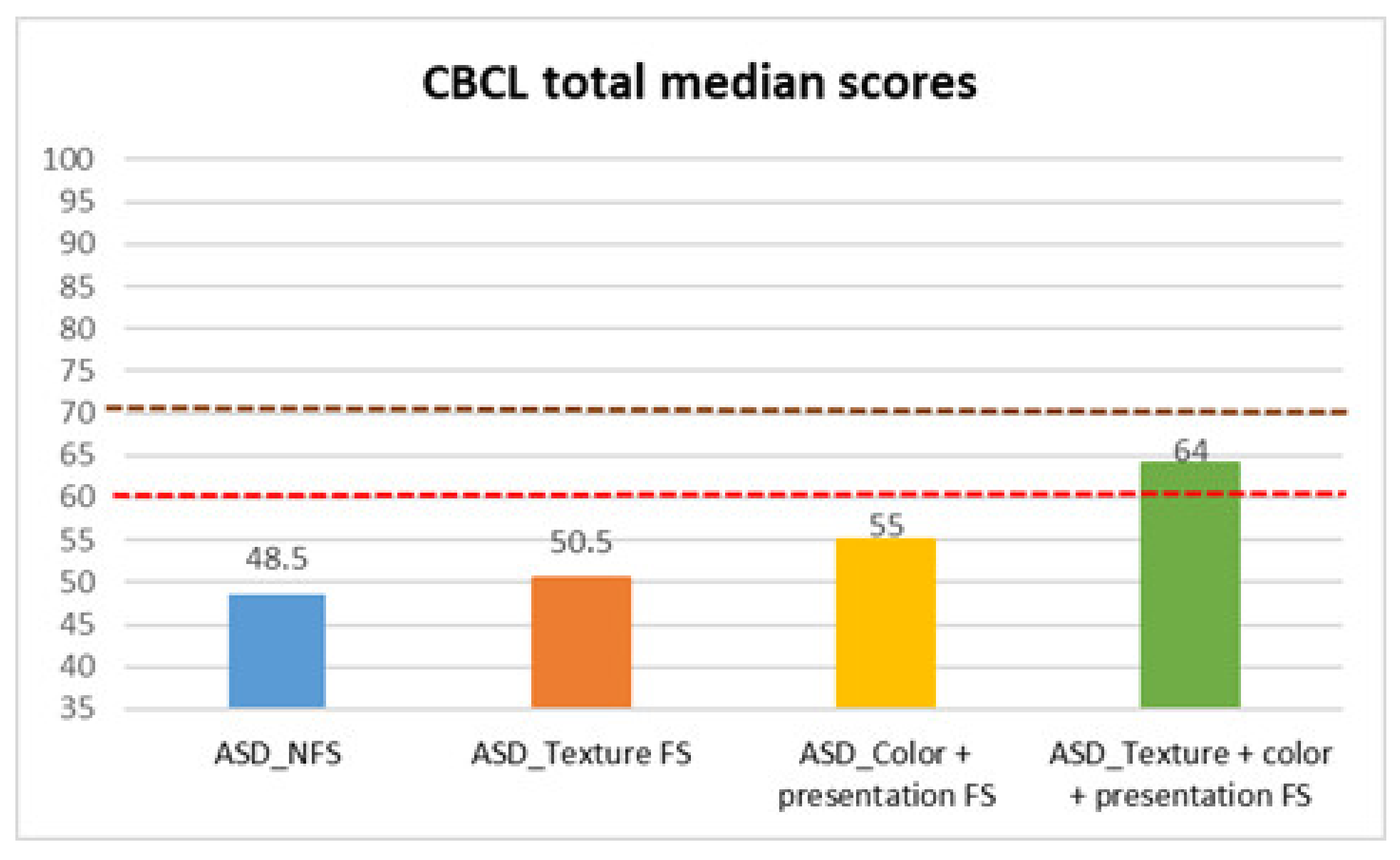

| CBCL total | ASD_NFS | Median | 48.50 |

| Standard deviation | 8.935 | ||

| ASD_FS | |||

| Texture FS | Median | 50.50 | |

| Standard deviation | 10.333 | ||

| Color + presentation FS | Median | 55.00 | |

| Standard deviation | 9.94 | ||

| Texture + color + presentation FS | Median | 64.00 | |

| Standard deviation | 9.715 | ||

| Subscale | NFS (Median) | FS (Median) | U | Z | p | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internalizing | 51 | 61 | 13,758.5 | 5.37 | <0.001 *** | 0.23 |

| Externalizing | 50 | 54.5 | 12,714.5 | 3.86 | <0.001 *** | 0.32 |

| Total | 48.5 | 55 | 12,782.0 | 3.95 | <0.001 *** | 0.23 |

| Subscale | χ2 | df | p | Post Hoc Pairwise Comparisons | p-Value | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBCL Internalizing | 31.947 | 3 | <0.001 | Texture FS vs. All FS | 0.035 * | 0.263 |

| Color + Presentation vs. All FS | 0.044 * | 0.241 | ||||

| NFS vs. Texture FS | <0.001 *** | 0.849 | ||||

| NFS vs. All FS | <0.001 *** | 0.936 | ||||

| CBCL Externalizing | 10.261 | 3 | 0.016 | NFS vs. All FS | <0.001 *** | 0.679 |

| CBCL Total | 10.658 | 3 | 0.014 | Color + Presentation FS vs. NFS | 0.004 ** | 0.308 |

| Texture FS vs. All FS | 0.009 ** | 0.402 | ||||

| Color + Presentation FS vs. All FS | 0.025 * | 0.298 |

| Model | R2 | Predictor | B | SE | β | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABAS_GAC | 0.176 | FS_Type | −2.386 | 0.806 | −0.161 | −2.961 | 0.003 ** |

| Gender | −4.652 | 2.019 | −0.125 | −2.304 | 0.022 * | ||

| Age_months | −0.373 | 0.076 | −0.277 | −4.924 | <0.001 *** | ||

| IQ | −7.965 | 1.807 | −0.264 | −4.409 | <0.001 *** | ||

| CSS_ADOS-2 | −1.178 | 0.607 | −0.114 | −1.941 | 0.053 | ||

| ABAS_DAC | 0.164 | FS_Type | −1.311 | 0.911 | −0.079 | −1.439 | 0.151 |

| Gender | −4.442 | 2.282 | −0.107 | −1.947 | 0.053 | ||

| Age_months | −0.379 | 0.086 | −0.251 | −4.427 | <0.001 *** | ||

| IQ | −9.594 | 2.042 | −0.284 | −4.699 | <0.001 *** | ||

| CSS_ADOS-2 | −1.623 | 0.686 | −0.14 | −2.366 | 0.019 * | ||

| ABAS_DAS | 0.187 | FS_Type | −1.407 | 0.775 | −0.098 | −1.815 | 0.071 |

| Gender | −4.193 | 1.942 | −0.117 | −2.159 | 0.032 * | ||

| Age_months | −0.373 | 0.073 | −0.286 | −5.122 | <0.001 *** | ||

| IQ | −6.577 | 1.738 | −0.225 | −3.785 | <0.001 *** | ||

| CSS_ADOS-2 | −2.084 | 0.584 | −0.208 | −3.571 | <0.001 *** | ||

| ABAS_DAP | 0.143 | FS_Type | −2.701 | 0.872 | −0.172 | −3.099 | 0.002 ** |

| Gender | −3.138 | 2.184 | −0.08 | −1.437 | 0.152 | ||

| Age_months | −0.387 | 0.082 | −0.271 | −4.733 | <0.001 *** | ||

| IQ | −6.148 | 1.954 | −0.192 | −3.146 | 0.002 ** | ||

| CSS_ADOS-2 | −1.308 | 0.656 | −0.119 | −1.992 | 0.047 * | ||

| CBCL_Internalizing | 0.126 | FS_Type | 3.101 | 0.567 | 0.307 | 5.467 | <0.001 *** |

| Gender | −0.863 | 1.421 | −0.034 | −0.608 | 0.544 | ||

| Age_months | 0.059 | 0.053 | 0.064 | 1.113 | 0.267 | ||

| IQ | 1.402 | 1.272 | 0.068 | 1.102 | 0.271 | ||

| CSS_ADOS-2 | 0.882 | 0.427 | 0.125 | 2.066 | 0.040 * | ||

| CBCL_Externalizing | 0.065 | FS_Type | 2.203 | 0.525 | 0.243 | 4.197 | <0.001 *** |

| Gender | −0.589 | 1.315 | −0.026 | −0.448 | 0.654 | ||

| Age_months | −0.024 | 0.049 | −0.029 | −0.487 | 0.627 | ||

| IQ | 0.512 | 1.177 | 0.028 | 0.436 | 0.664 | ||

| CSS_ADOS-2 | 0.216 | 0.395 | 0.034 | 0.547 | 0.584 | ||

| CBCL_Total | 0.100 | FS_Type | 2.876 | 0.56 | 0.292 | 5.137 | <0.001 *** |

| Gender | −0.346 | 1.403 | −0.014 | −0.246 | 0.805 | ||

| Age_months | 0.019 | 0.053 | 0.022 | 0.367 | 0.714 | ||

| IQ | 0.603 | 1.255 | 0.03 | 0.481 | 0.631 | ||

| CSS_ADOS-2 | 0.636 | 0.422 | 0.092 | 1.509 | 0.132 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sarnataro, R.; Siracusano, M.; Campanile, R.; Marcovecchio, C.; Babolin, S.; Riccioni, A.; Arturi, L.; Mazzone, L. Relationship Between Food Selectivity, Adaptive Functioning and Behavioral Profile in Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1664. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121664

Sarnataro R, Siracusano M, Campanile R, Marcovecchio C, Babolin S, Riccioni A, Arturi L, Mazzone L. Relationship Between Food Selectivity, Adaptive Functioning and Behavioral Profile in Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1664. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121664

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarnataro, Rachele, Martina Siracusano, Roberta Campanile, Claudia Marcovecchio, Silvia Babolin, Assia Riccioni, Lucrezia Arturi, and Luigi Mazzone. 2025. "Relationship Between Food Selectivity, Adaptive Functioning and Behavioral Profile in Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 12: 1664. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121664

APA StyleSarnataro, R., Siracusano, M., Campanile, R., Marcovecchio, C., Babolin, S., Riccioni, A., Arturi, L., & Mazzone, L. (2025). Relationship Between Food Selectivity, Adaptive Functioning and Behavioral Profile in Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Behavioral Sciences, 15(12), 1664. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121664