Temporal Associations Between Sport Participation, Dropout from Sports, and Mental Health Indicators: A Two-Year Follow-Up Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Results

3.2. Results from the Latent Change Score Analyses

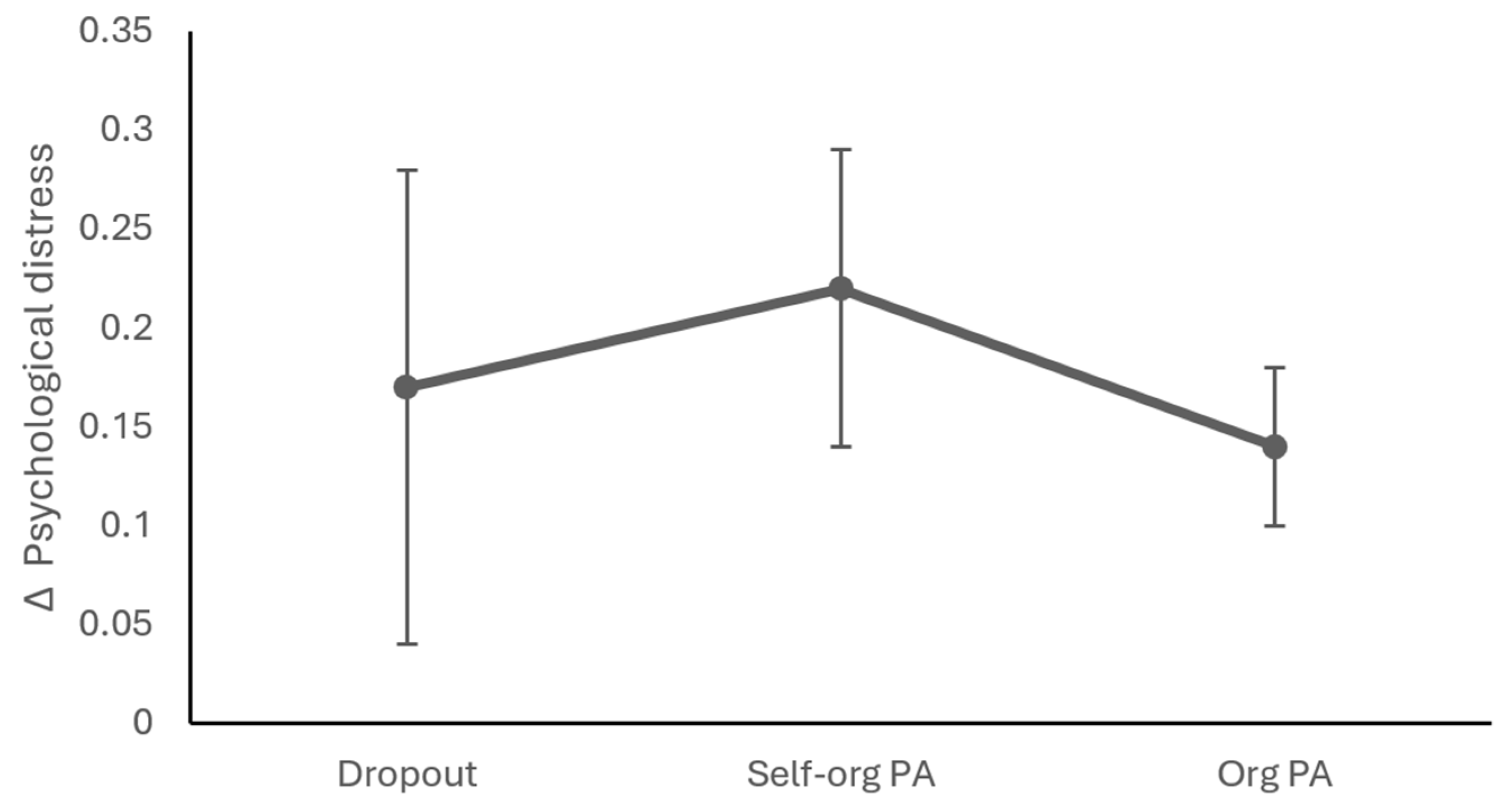

3.2.1. Psychological Distress Symptoms

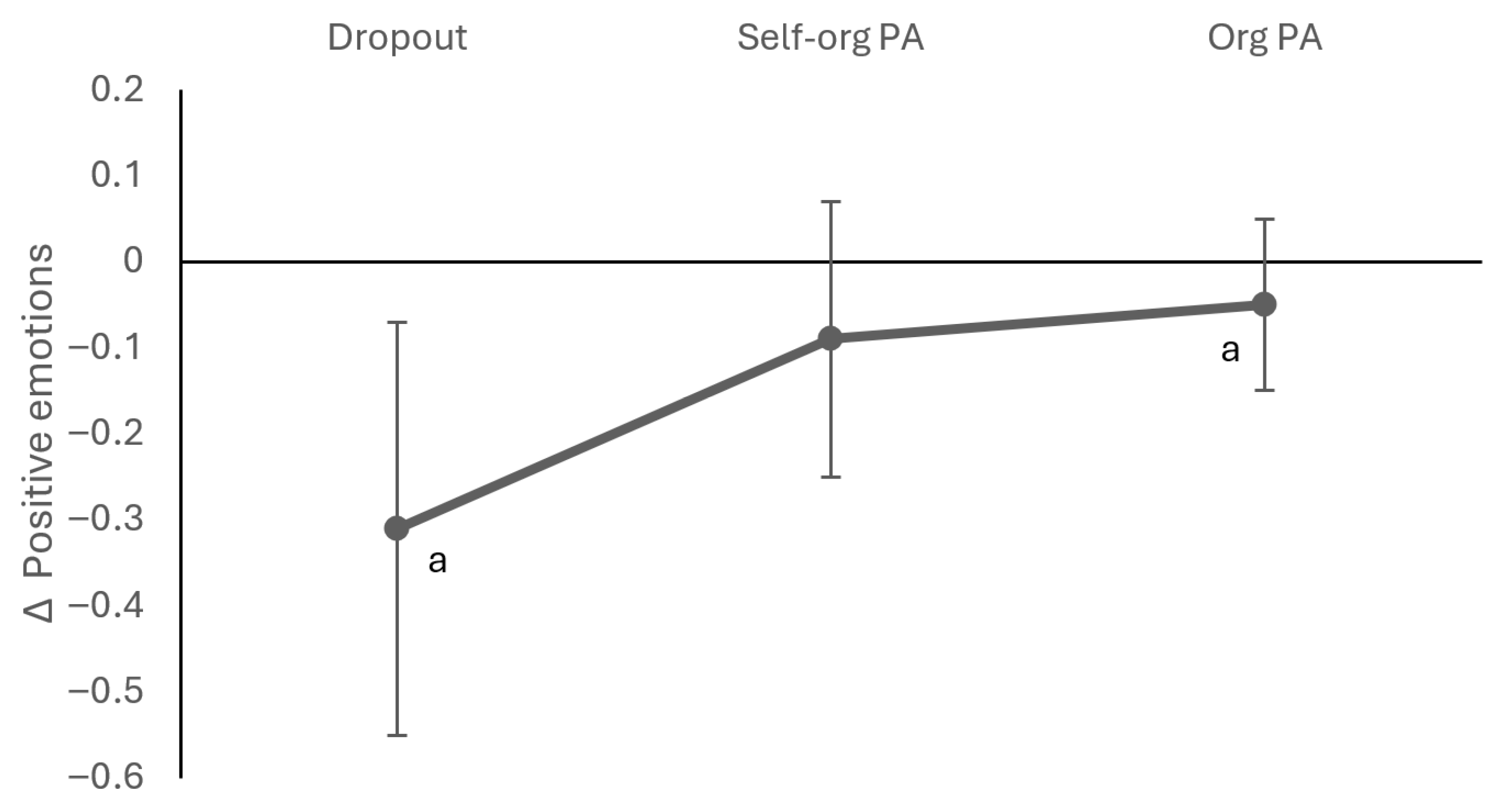

3.2.2. Positive Emotions

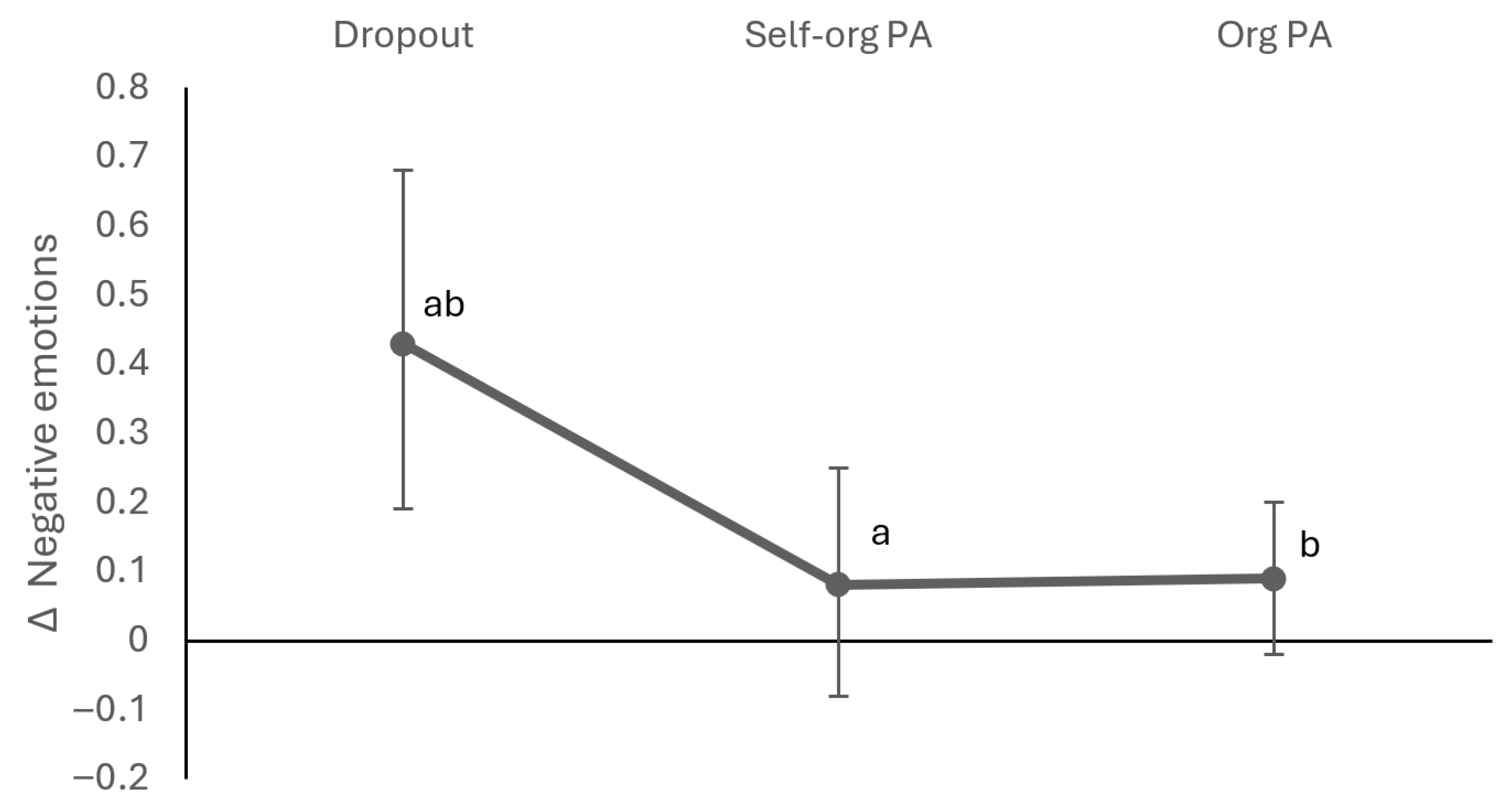

3.2.3. Negative Emotions

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Implications

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LCS | latent change score |

| PSRF | potential scale reduction factor |

| MCMC | Markov chain Monte Carlo |

| PPp | posterior predictive p |

| CI | Credibility Interval |

Appendix A

References

- Agnafors, S., Barmark, M., & Sydsjö, G. (2020). Mental health and academic performance: A study on selection and causation effects from childhood to early adulthood. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 56(5), 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bean, C., McFadden, T., Fortier, M., & Forneris, T. (2021). Understanding the relationships between programme quality, psychological needs satisfaction, and mental well-being in competitive youth sport. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 19(2), 246–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bean, C. N., Fortier, M., Post, C., & Chima, K. (2014). Understanding how organized youth sport may be harming individual players within the family unit: A literature review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11(10), 10226–10268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botha, F., Morris, R. W., Butterworth, P., & Glozier, N. (2023). Generational differences in mental health trends in the twenty-first century. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(49), e2303781120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, A. I., Davidsen, M., Koushede, V., & Juel, K. (2020). Mental health and the risk of negative social life events: A prospecti ve cohort study among the adult Danish population. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 50(2), 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derogatis, L. R., Lipman, R. S., Rickels, K., Uhlenhuth, E. H., & Covi, L. (1974). The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): A self-report symptom inventory. Behavioral Science, 19(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eather, N., Wade, L., Pankowiak, A., & Eime, R. (2023). The impact of sports participation on mental health and social outcomes in adults: A systematic review and the ‘Mental Health through Sport’ conceptual model. Systematic Reviews, 12(1), 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eime, R. M., Young, J. A., Harvey, J. T., Charity, M. J., & Payne, W. R. (2013). A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for children and adolescents: Informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 10(1), 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdvik, I. B., Haugen, T., Ivarsson, A., & Säfvenbom, R. (2019). Global self-worth among adolescents: The role of basic psychological need satisfaction in physical education. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 64(5), 768–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galderisi, S. (2024). The need for a consensual definition of mental health. World Psychiatry, 23(1), 52–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graupensperger, S., Sutcliffe, J., & Vella, S. A. (2021). Prospective associations between sport participation and indices of mental health across adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(7), 1450–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, M. D., Barnes, J. D., Tremblay, M. S., & Guerrero, M. D. (2022). Associations between organized sport participation and mental health difficulties: Data from over 11,000 US children and adolescents. PLoS ONE, 17(6), e0268583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, D., & Depaoli, S. (2012). Bayesian structural equation modeling. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Handbook of structural equation modeling (pp. 650–673). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kleppang, A. L., & Hagquist, C. (2016). The psychometric properties of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-10: A Rasch analysis based on adolescent data from Norway. Family Practice, 33(6), 740–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krokstad, S., Weiss, D. A., Krokstad, M. A., Rangul, V., Kvaløy, K., Ingul, J. M., Bjerkeset, O., Twenge, J., & Sund, E. R. (2022). Divergent decennial trends in mental health according to age reveal po orer mental health for young people: Repeated cross-sectional populati on-based surveys from the HUNT Study, Norway. BMJ Open, 12(5), e057654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamers, S. M. A., Westerhof, G. J., Kovács, V., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2012). Differential relationships in the association of the Big Five personality traits with positive mental health and psychopathology. Journal of Research in Personality, 46(5), 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layous, K., Chancellor, J., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2014). Positive activities as protective factors against mental health conditions. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 123(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, I. (2020). Analysing policy change and continuity: Physical education and school sport policy in England since 2010. Sport, Education and Society, 25(1), 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Barrado, A. D., & Gomez-Baya, D. (2024). A scoping review of the research evidence of the developmental assets model in Europe [Original Research]. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1407338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McArdle, J. J., & Nesselroade, J. R. (2014). Longitudinal data analysis using structural equation models. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Merkel, D. L. (2013). Youth sport: Positive and negative impact on young athletes. Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine, 4, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthén, B., & Asparouhov, T. (2012). Bayesian structural equation modeling: A more flexible representation of substantive theory. Psychological Methods, 17(3), 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Occhipinti, J.-A., Hynes, W., Geli, P., Eyre, H. A., Song, Y., Prodan, A., Skinner, A., Ujdur, G., Buchanan, J., Green, R., Rosenberg, S., Fels, A., & Hickie, I. B. (2023). Building systemic resilience, productivity and well-being: A Mental We alth perspective. BMJ Global Health, 8(9), e012942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, J., Jeanes, R., Magee, J., Spaaij, R., Penney, D., & Miyashita, S. (2025). What is informal sport? Negotiating contemporary sporting forms. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 49(2–3), 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orben, A., Lucas, R. E., Fuhrmann, D., & Kievit, R. A. (2022). Trajectories of adolescent life satisfaction. Royal Society Open Science, 9(8), 211808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panza, M. J., Graupensperger, S., Agans, J. P., Doré, I., Vella, S. A., & Evans, M. B. (2020). Adolescent sport participation and symptoms of anxiety and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 42(3), 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Säfvenbom, R., Geldhof, G. J., & Haugen, T. (2014). Sports clubs as accessible developmental assets for all? Adolescents’ assessment of egalitarianism vs. elitism in sport clubs vs. school. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 6(3), 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Säfvenbom, R., Strittmatter, A.-M., & Bernhardsen, G. P. (2023). Developmental outcomes for young people participating in informal and lifestyle sports: A scoping review of the literature, 2000–2020. Social Sciences, 12(5), 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamnes, C. K., Bekkhus, M., Eilertsen, M., Nes, R. B., Prydz, M. B., Ystrom, E., Aksnes, E. R., Andersen, S. N., Ask, H., Ayorech, Z., Baier, T., Beck, D., Berger, E. J., Bjørndal, L. D., Boer, O. D., Bos, M. G. N., Caspi, A., Cheesman, R., Chegeni, R., … von Soest, T. (2025). The nature of the relation between mental well-being and ill-being. Nature Human Behaviour, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vella, S. A. (2019). Mental health and organized youth sport. Kinesiology Review, 8(3), 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, S. A., Cliff, D. P., Magee, C. A., & Okely, A. D. (2015). Associations between sports participation and psychological difficulties during childhood: A two-year follow up. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 18(3), 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, S. A., Swann, C., Allen, M. S., Schweickle, M. J., & Magee, C. A. (2017). Bidirectional associations between sport involvement and mental health in adolescence. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 49(4), 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittersø, J., Dyrdal, G. M., & Røysamb, E. (2005, June 16–18). Utilities and capabilities: A psychological account of the two concepts and their relation to the idea of a good life. 2nd Workshop on Capabilities and Happiness, Milan, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- von Simson, K., Brekke, I., & Hardoy, I. (2021). The impact of mental health problems in adolescence on educational att ainment. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 66(2), 306–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Soest, T., Kozák, M., Rodríguez-Cano, R., Fluit, D. H., Cortés-García, L., Ulset, V. S., Haghish, E. F., & Bakken, A. (2022). Adolescents’ psychosocial well-being one year after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in Norway. Nature Human Behaviour, 6(2), 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zyphur, M. J., & Oswald, F. L. (2015). Bayesian estimation and inference: A user’s guide. Journal of Management, 41(2), 390–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Full Sample M (SD) | Dropouts Group 1 M (SD) | Convertors Group 2 M (SD) | Stayers Group 3 M (SD) | Correlation (r) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |||||

| 1. Distress Symptoms T1 | 1.51 (0.53) | 1.56 (0.61) | 1.57 (0.53) | 1.42 (0.47) | 0.53 * | 0.49 * | 0.36 * | −0.25 * | −0.17 * | |

| 2. Distress Symptoms T2 | 1.64 (0.67) | 1.72 (0.73) | 1.79 (0.73) | 1.56 (0.62) | 0.33 * | 0.54 * | −0.13 * | −0.22 * | ||

| 3. Negative affects T1 | 2.96 (1.19) | 2.79 (1.01) | 3.10 (1.16) | 2.81 (1.12) | 0.36 * | −0.06 | −0.11 * | |||

| 4. Negative affects T2 | 3.03 (1.33) | 3.20 (1.38) | 3.19 (1.36) | 2.91 (1.29) | −0.14 * | −0.07 | ||||

| 5. Positive affects T1 | 5.11 (1.13) | 4.89 (1.22) | 4.91 (1.14) | 5.28 (1.05) | 0.41 * | |||||

| 6. Positive affects T2 | 5.06 (1.22) | 4.60 (1.26) | 4.83 (1.27) | 5.23 (1.17) | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Säfvenbom, R.; Haugen, T.; Sandsaunet Ulset, V.; Ivarsson, A. Temporal Associations Between Sport Participation, Dropout from Sports, and Mental Health Indicators: A Two-Year Follow-Up Study. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1665. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121665

Säfvenbom R, Haugen T, Sandsaunet Ulset V, Ivarsson A. Temporal Associations Between Sport Participation, Dropout from Sports, and Mental Health Indicators: A Two-Year Follow-Up Study. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1665. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121665

Chicago/Turabian StyleSäfvenbom, Reidar, Tommy Haugen, Vidar Sandsaunet Ulset, and Andreas Ivarsson. 2025. "Temporal Associations Between Sport Participation, Dropout from Sports, and Mental Health Indicators: A Two-Year Follow-Up Study" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 12: 1665. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121665

APA StyleSäfvenbom, R., Haugen, T., Sandsaunet Ulset, V., & Ivarsson, A. (2025). Temporal Associations Between Sport Participation, Dropout from Sports, and Mental Health Indicators: A Two-Year Follow-Up Study. Behavioral Sciences, 15(12), 1665. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121665