Youth Engagement in School Mental Health Teaming: Structure, Processes, and Outcomes of a Youth Leadership Academy to Promote Emotional Well-Being in Schools

Abstract

1. Introduction

Current Study Aims

2. YLA Program Delivery

2.1. YLA Background, Purpose, & Structure

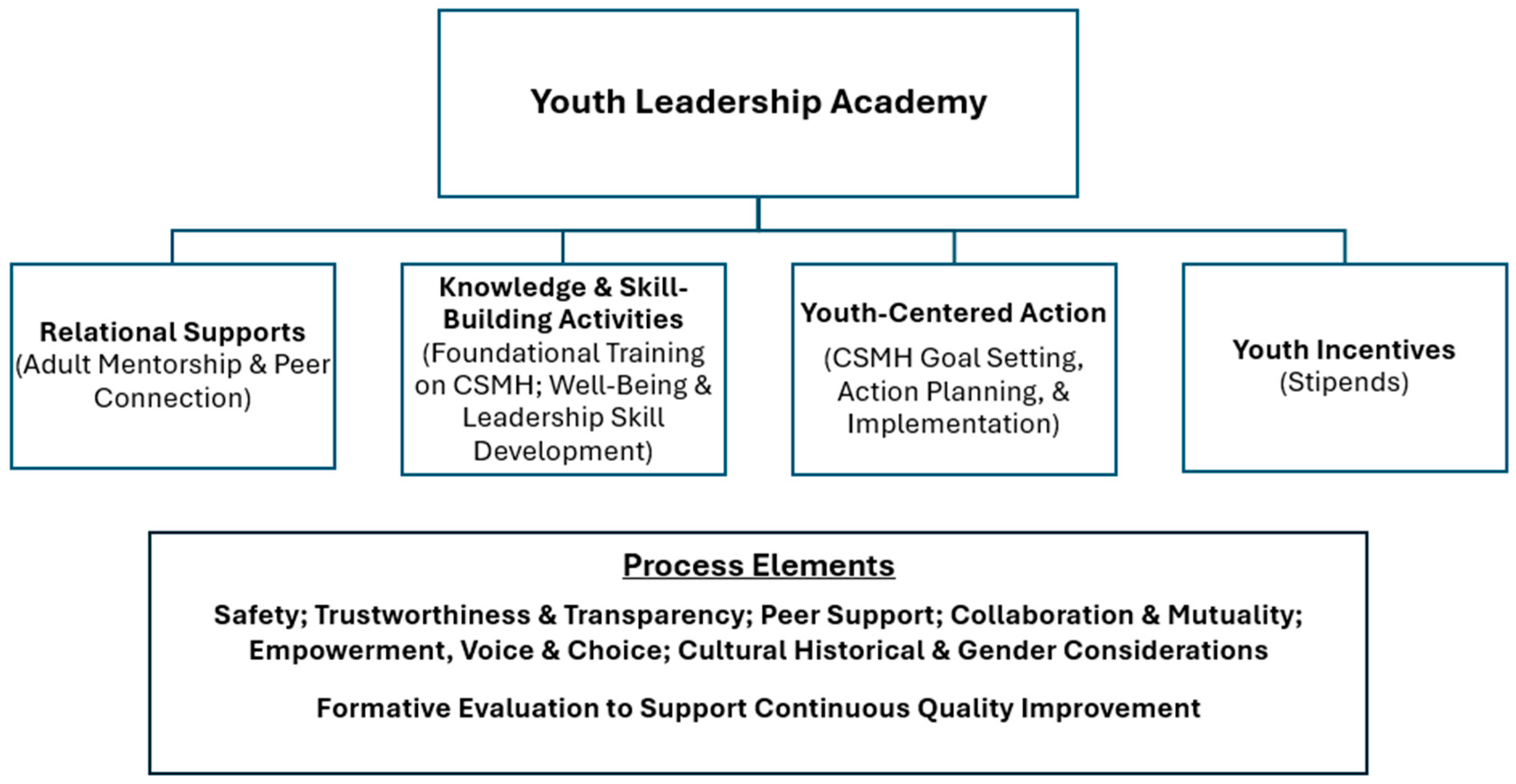

2.2. YLA Program Components

2.2.1. Relational Supports

2.2.2. Knowledge- and Skill-Building Activities

2.2.3. Youth-Centered Action

2.2.4. Youth Incentives

2.2.5. The YLA Process of Engagement

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Recruitment

3.3. Procedures

3.4. Ethical Considerations

3.5. Measures

3.5.1. Youth SMART Goal Questionnaire

3.5.2. Core Social and Emotional Skills Survey

4. Results

4.1. Youth Leader Multi-Tiered System of Support Contributions

4.1.1. Thematic Analysis of Youth-Driven MTSS Goals

4.1.2. Mental Health Literacy

4.1.3. School Climate

4.1.4. Educator Professional Development

4.1.5. Social and Emotional Learning

4.1.6. Educator Well-Being

4.1.7. Small Group Counseling

4.1.8. Peer Mentoring

4.2. Youth Leader Positive Youth Development

5. Discussion

5.1. Youth Contributions to MTSS

5.2. Youth Positive Development

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CSMH | Comprehensive School Mental Health |

| LC | Learning Collaborative |

| DYL | District Youth Liaison |

| MHL | Mental Health Literacy |

| MTSS | Multi-Tiered System of Support |

| NCSMH | National Center for School Mental Health |

| PD | Professional Development |

| SEL | Social and Emotional Learning |

| RISE | Supportive, responsive Relationships; Intentional learning experiences and interventions; Skills development; and Emotionally supportive environments that promote belonging |

| SMART | Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, Time-Bound |

| WSCC | Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child |

| YLA | Youth Leadership Academy |

References

- Bohnenkamp, J., Robinson, P., Connors, E., Carter, T., Orenstein, S., Reaves, S., Hoover, S., & Lever, N. (2024). Improving school mental health via national learning collaboratives with state and local teams: Components, feasibility, and initial impacts. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 47(4), 402–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). About the Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child (WSCC) model. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/whole-school-community-child/about/ (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Cheryan, S., Ziegler, S. A., Plaut, V. C., & Meltzoff, A. N. (2014). Designing classrooms to maximize student achievement. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 1(1), 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colomeischi, A. A., Duca, D. S., Bujor, L., & Rusu, P. P. (2022). Impact of a school mental health program on children’s and adolescents’ socio-emotional skills and psychosocial difficulties. Children, 9(11), 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copeland, W. E., Wolke, D., Angold, A., & Costello, E. J. (2013). Adult psychiatric outcomes of bullying and being bullied by peers in childhood and adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(4), 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolaty, S., Midouhas, E., Deighton, J., & Somerville, M. P. (2025). Public participation in mental health programming: Insights into the ways young people are involved in the development, delivery, and evaluation of mental health initiatives in school and community spaces. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 30(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, G. T. (1981). There’s a SMART way to write management’s goals and objectives. Management Review, 70(11), 35–36. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, L. J., Jackson, D., Woods, C., & Usher, K. (2019). Rewriting stories of trauma through peer-to-peer mentoring for and by at-risk young people. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 28(3), 744–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fein, E. H., Agbangnin, G., Murillo-León, J., Parsons, M., Sakai-Bismark, R., Martinez, A., Gomez, P. F., Chung, B., Chung, P., Dudovitz, R., Inkelas, M., & Kataoka, S. (2023). Encouraging “positive views” of mental illness in high schools: An evaluation of Bring Change 2 Mind youth engagement clubs. Health Promotion Practice, 24(5), 873–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felter, J., Chung, H. L., Guth, A., & DiDonato, S. (2023). Implementation and outcomes of the Trauma Ambassadors Program: A case study of trauma-informed youth leadership development. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 41, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golberstein, E., Wen, H., & Miller, B. F. (2023). Effects of school-based mental health services on youth outcomes. Journal of Human Resources, 59(S), S256–S281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Moreno, A., & Molero Jurado, M. d. M. (2024). Intervention programs for the prevention of bullying and the promotion of prosocial behaviors in adolescence: A systematic review. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 10, 100954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardino, C. A., & Fullerton, E. (2010). Changing behaviors by changing the classroom environment. Teaching Exceptional Children, 42(6), 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, R. A. (1992). Children’s participation: From tokenism to citizenship. UNICEF International Child Development Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Hello Insight. (2021). HI SEL: Technical report summary. Available online: https://ins.gt/drDY6F (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Hoover, S., & Bostic, J. (2021). Schools as a vital component of the child and adolescent mental health system. Psychiatric Services, 72(1), 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoover, S., Lever, N., Sachdev, N., Bravo, N., Schlitt, J., Acosta Price, O., Sheriff, L., & Cashman, J. (2019). Advancing comprehensive school mental health: Guidance from the field. National Center for School Mental Health, University of Maryland School of Medicine. Available online: https://www.schoolmentalhealth.org/media/som/microsites/ncsmh/documents/bainum/Advancing-CSMHS_September-2019.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Jankowska-Tvedten, A., & Wiium, N. (2023). Positive youth identity: The role of adult social support. Youth, 3(3), 869–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, E., Kindler, C., Saint Amour, A. T., Locus, K., Hosaka, K. R. J., Leslie, M. C., & Patel, N. A. (2024). Youth engagement synergy in mental health legislation and programming. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 33(4), 741–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, S., Sharma, V., Fortune, S., Wadman, R., Churchill, R., & Hetrick, S. (2022). Adapting a codesign process with young people to prioritize outcomes for a systematic review of interventions to prevent self-harm and suicide. Health Expectations, 25(4), 1393–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutcher, S., Wei, Y., & Coniglio, C. (2016). Mental health literacy: Past, present, and future. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 61(3), 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, R. M., Lerner, J. V., Almerigi, J. B., Theokas, C., Phelps, E., Gestsdottir, S., Naudeau, S., Jelicic, H., Alberts, A., Ma, L., Smith, L. M., Bobek, D. L., Richman-Raphael, D., Simpson, I., Christiansen, E. D., & von Eye, A. (2005). Positive youth development, participation in community youth development programs, and community contributions of fifth-grade adolescents: Findings from the first wave of the 4-H study of positive youth development. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 25(1), 17–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lever, N., Orenstein, S., Jaspers, L., Bohnenkamp, J., Chung, J., & Hager, E. (2024). Using the whole school, whole community, whole child model to support mental health in schools. Journal of School Health, 94(2), 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawn, L., Welsh, P., Stain, H. J., & Windebank, P. (2015). Youth Speak: Increasing engagement of young people in mental health research. Journal of Mental Health, 24(5), 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, E., Amarbayan, M. M., Rabi, S., Mendoza, J., Naqvi, S. F., Thapa Bajgain, K., Zwicker, J. D., & Santana, M. (2023). Youth engagement in mental health research: A systematic review. Health Expectations, 26(1), 30–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, S., Teie, S., McCutchen, J., & Geller, E. S. (2016). Actively caring to prevent bullying in an elementary school: Prompting and rewarding prosocial behavior. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 44(3), 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, M. W. (2000). Community counts: How youth organizations matter for youth development. Public Education Network. [Google Scholar]

- Meissel, K., & Yao, E. S. (2024). Using Cliff’s delta as a non-parametric effect size measure: An accessible web app and R tutorial. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 29(1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, J., Espiritu, R. C., Horen, N., Sebian, J., & Waetzig, E. (2010). A public health approach to children’s mental health: A conceptual framework. Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development, National Technical Assistance Center for Children’s Mental Health. Available online: https://gucchd.georgetown.edu/products/PublicHealthApproach.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2019). The promise of adolescence: Realizing opportunity for all youth. National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for School Mental Health (NCSMH). (2023a). School mental health quality guide: Mental health promotion services and supports (tier 1). NCSMH, University of Maryland School of Medicine. Available online: https://www.schoolmentalhealth.org/media/som/microsites/ncsmh/documents/quality-guides/Tier-1.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- National Center for School Mental Health (NCSMH). (2023b). School mental health quality guide: Early intervention and treatment services and supports (tiers 2 and 3). NCSMH, University of Maryland School of Medicine. Available online: https://dm0gz550769cd.cloudfront.net/shape/4e/4e4b6e2ceedead1d62c06197e75f5768.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- O’Connor, C. A., Dyson, J., Cowdell, F., & Watson, R. (2018). Do universal school-based mental health promotion programmes improve the mental health and emotional wellbeing of young people? A literature review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(3–4), e412–e426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozer, E. J., & Douglas, L. (2013). The impact of participatory research on urban teens: An experimental evaluation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 51(1–2), 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonert-Reichl, K. A. (2017). Social and emotional learning and teachers. The Future of Children, 27(1), 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4884. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Available online: https://scholarworks.boisestate.edu/covid/7/ (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Weist, M. D., Eber, L., Horner, R., Splett, J., Putnam, R., Barrett, S., Perales, K., Fairchild, A. J., & Hoover, S. (2018). Improving multi-tiered systems of support for students with “internalizing” emotional/behavioral problems. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 20(3), 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Subtheme (MTSS Domain) | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Tier 1: Universal Mental Health Promotion/Prevention | |

| Mental Health Literacy | 30 |

| School Climate | 25 |

| Educator PD | 2 |

| Social and Emotional Learning | 2 |

| Educator Well-Being | 1 |

| Tier 2: Early Intervention | |

| Small Group Counseling | 1 |

| Peer Mentoring * | 1 |

| Tier 3: Treatment | |

| Not applicable | - |

| Domain | Pre-Test M | Post-Test M |

|---|---|---|

| Core Emotional and Social Skills | 83.88 | 86.81 |

| Academic Self-Efficacy | 90.39 | 93.37 |

| Contribution | 78.08 | 81.36 |

| Positive Identity | 81.46 | 86.72 |

| Self-Management | 80.22 | 83.42 |

| Social Skills | 90.78 | 90.24 |

| Domain | Pre-Test M | Post-Test M | z | p | δ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core Emotional and Social Skills * | 83.38 | 86.81 | 2.34 | 0.02 | 0.22 |

| Academic Self-Efficacy | 90.52 | 93.37 | 1.50 | 0.13 | 0.22 |

| Contribution * | 77.51 | 81.36 | 2.06 | 0.04 | 0.20 |

| Positive Identity * | 80.26 | 86.72 | 1.98 | 0.04 | 0.28 |

| Self-Management | 79.34 | 83.42 | 1.49 | 0.14 | 0.28 |

| Social Skills | 90.96 | 90.24 | −0.11 | 0.91 | −0.09 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Beason, T.S.; Ladhani, Z.; Robinson, P.; Trainor, K.M.; Russo, J.E.; Bernstein, J.; Bohnenkamp, J.H. Youth Engagement in School Mental Health Teaming: Structure, Processes, and Outcomes of a Youth Leadership Academy to Promote Emotional Well-Being in Schools. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1563. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111563

Beason TS, Ladhani Z, Robinson P, Trainor KM, Russo JE, Bernstein J, Bohnenkamp JH. Youth Engagement in School Mental Health Teaming: Structure, Processes, and Outcomes of a Youth Leadership Academy to Promote Emotional Well-Being in Schools. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1563. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111563

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeason, Tiffany S., Zahra Ladhani, Perrin Robinson, Kathryn M. Trainor, Jenna E. Russo, Jessica Bernstein, and Jill H. Bohnenkamp. 2025. "Youth Engagement in School Mental Health Teaming: Structure, Processes, and Outcomes of a Youth Leadership Academy to Promote Emotional Well-Being in Schools" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1563. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111563

APA StyleBeason, T. S., Ladhani, Z., Robinson, P., Trainor, K. M., Russo, J. E., Bernstein, J., & Bohnenkamp, J. H. (2025). Youth Engagement in School Mental Health Teaming: Structure, Processes, and Outcomes of a Youth Leadership Academy to Promote Emotional Well-Being in Schools. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1563. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111563