Factors Influencing Telemedicine Adoption Among Healthcare Professionals in Geriatric Medical Centers: A Technology Acceptance Model Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Telemedicine: Definition and Benefits

1.2. Challenges in Telemedicine Adoption

1.3. Theoretical Framework: Technology Acceptance Model (TAM)

1.4. Behavioral Factors Influencing Telemedicine Adoption

1.5. Study Aims and Hypotheses

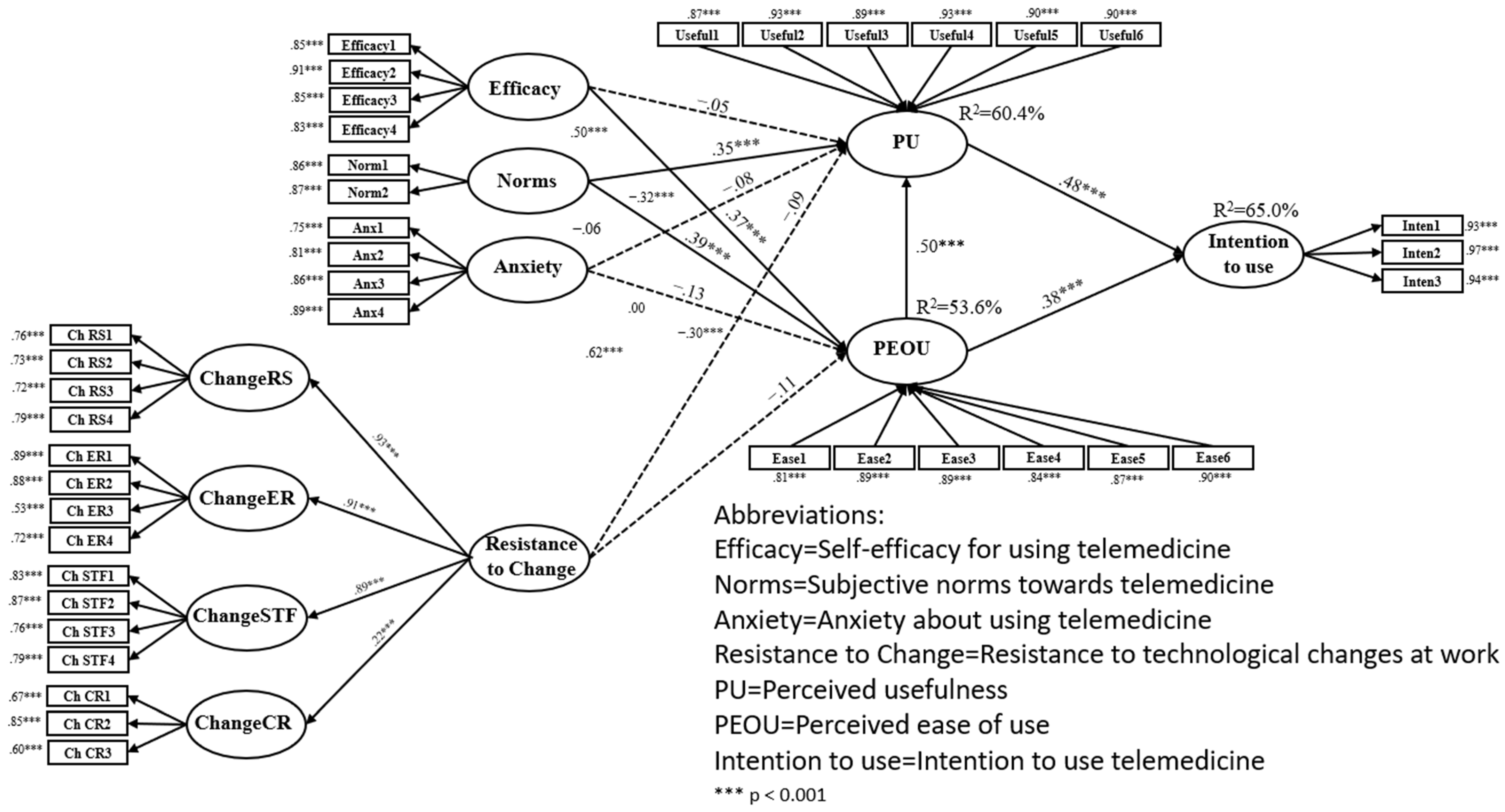

- Perceived ease of use of telemedicine will mediate the relationship between self-efficacy for using telemedicine and the PU of telemedicine in the geriatric care context.Following studies showing that subjective norms positively affect technology acceptance through PEOU (Lazarus et al., 2021; Schepers & Wetzels, 2007) in healthcare professional communities we hypothesize that:

- Perceived ease of use of telemedicine will mediate the relationship between subjective norms towards telemedicine and the PU of telemedicine among interdisciplinary geriatric care teams.Given findings that technology anxiety negatively impacts PEOU (Guo et al., 2013; Tsai et al., 2020), we hypothesize

- Perceived ease of use of telemedicine will mediate the relationship between anxiety about using telemedicine and PU in the specialized geriatric care environment.Based on evidence that resistance to change correlates negatively with PEOU (Guo et al., 2013; Liao et al., 2016), we hypothesize that:

- Perceived ease of use of telemedicine will mediate the relationship between resistance to technological changes at work and the PU of telemedicine in government geriatric medical centers.Consistent with TAM’s core proposition that PU mediates between PEOU and intention to use (Chavoshi & Hamidi, 2019; Davis, 1989) and extending this to the unique demands of geriatric care where efficiency must balance with relationship-centered care we hypothesize that:

- PU of telemedicine will mediate the relationship between PEOU of telemedicine and intention to use telemedicine in government geriatric medical centers.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Instrument

- Self-efficacy for using telemedicine: This variable was measured using a 4-item scale adapted from Venkatesh et al. (2003). Example item: “I could complete a job or task using telemedicine if there was no one around to tell me what to do as I go.” Participants rated their self-efficacy on a scale from 1 to 10, with 1 indicating “not at all confident,” 5 indicating “moderately confident,” and 10 indicating “completely confident” (Venkatesh et al., 2003). The internal consistency reliability found was 0.87.

- Subjective norms towards telemedicine: This variable was measured using a 2-item scale from Venkatesh et al. (2003). Example item: “People who influence my behavior think that I should use telemedicine in my work.” A 7-point Likert scale was used, ranging from 1 “strongly disagree” to 7 “strongly agree” (Venkatesh et al., 2003). The internal consistency reliability found was above 0.70.

- Anxiety about using telemedicine: This variable was measured using a 4-item scale from Venkatesh et al. (2003). Example item: “I feel apprehensive about using telemedicine in my work.” A 6-point Likert scale was used, ranging from 1 “strongly disagree” to 6 “strongly agree” (Venkatesh et al., 2003). The internal consistency reliability was 0.82.

- Resistance to technological changes at work: This variable was measured using a 17-item scale developed by Oreg et al. (2008), consisting of four categories: routine seeking, emotional reaction to change, short-term focus, and cognitive rigidity. Example item: “When my work procedures change, it seems like a real hassle to me.” A 6-point Likert scale was used, ranging from 1 “strongly disagree” to 6 “strongly agree.”. The internal consistency reliability was 0.85.

- PU of telemedicine: This variable was measured using a 6-item scale adapted from Davis (1989). Example item: “Using telemedicine would be useful in my job.” A 7-point Likert scale was used, ranging from 1 “strongly disagree” to 7 “strongly agree” (Davis, 1989). The internal consistency reliability found was above 0.70.

- Perceived ease of use of telemedicine: This variable was measured using a 6-item scale adapted from Davis (1989). Example item: “I would find it easy to use telemedicine in my work.” A 7-point Likert scale was used, ranging from 1 “strongly disagree” to 7 “strongly agree” (Davis, 1989). The internal consistency reliability was above 0.70.

- Intention to use telemedicine: This variable was measured using a 3-item scale from Davis (1989). Example item: “I intend to use telemedicine technology in my work in the near future” (Davis, 1989). A 7-point Likert scale was used, ranging from 1 “strongly disagree” to 7 “strongly agree.” The internal consistency reliability was 0.89.

- Demographic and Background Data: Demographic and professional background data were collected to contextualize behavioral patterns. Personal demographics included gender, age, marital status, parental status (including number of children), religion, and level of religiosity, capturing personal and cultural factors that may influence technology adoption behaviors. Professional characteristics encompassed job role (physician, nurse, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, social worker, speech therapist, clinical dietitian), years of professional experience, and work schedule patterns (morning only versus rotating shifts), etc. The back-translation process was conducted by professional translators, including one native English speaker who verified the accuracy and linguistic appropriateness of the final English version.

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

Multigroup Analysis Findings

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Future Research Directions

4.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aggelidis, V. P., & Chatzoglou, P. D. (2008). Using a modified technology acceptance model in hospitals. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 8, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almathami, H. K. Y., Win, K. T., & Vlahu-Gjorgievska, E. (2020). Barriers and facilitators that influence telemedicine-based, real-time, online consultation at patients’ homes: Systematic literature review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(2), e16407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R. P. (2007). The legacy of the technology acceptance model and a proposal for a paradigm shift. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 8(4), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1981). Self-referent thought: A developmental analysis of self-efficacy. Social Cognitive Development: Frontiers and Possible Futures, 200(1), 239. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashshur, R., Doarn, C. R., Frenk, J. M., Kvedar, J. C., & Woolliscroft, J. O. (2020). Telemedicine and the COVID-19 pandemic, lessons for the future. Telemedicine and e-Health, 26(5), 571–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacherjee, A., & Hikmet, N. (2007). Physicians’ resistance toward healthcare information technology: A theoretical model and empirical test. European Journal of Information Systems, 16(6), 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, K., Ziewers, S., Brandt, M. P., Sparwasser, P., Haack, M., Willems, F., & Borgmann, H. (2020). Telemedicine online visits in urology during the COVID-19 pandemic—potential, risk factors, and patients’ perspective. European Urology, 78(1), 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bornstein, M. H., Jager, J., & Putnick, D. L. (2013). Sampling in developmental science: Situations, shortcomings, solutions, and standards. Developmental Review, 33(4), 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, L., & Bélanger, F. (2005). The utilization of e-government services: Citizen trust, innovation and acceptance factors. Information Systems Journal, 15(1), 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Global research on coronavirus disease (COVID-19). World Health Organization (WHO). [Google Scholar]

- Chavoshi, A., & Hamidi, H. (2019). Social, individual, technological and pedagogical factors influencing mobile learning acceptance in higher education: A case from Iran. Telematics and Informatics, 38, 133–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, C. (2020). The hidden digital divide: How digital health literacy is associated with socioeconomic status, education, and age in the United Kingdom no title. Capella University. [Google Scholar]

- Compeau, D. R., & Higgins, C. A. (2017). Development of a measure and initial test. MIS Quarterly, 22(19), 189–211. [Google Scholar]

- Coppini, V., Ferraris, G., Ferrari, M. V., Monzani, D., Dahò, M., Fragale, E., Grasso, R., Pietrobon, R., Machiavelli, A., & Teixeira, L. (2025). The Beacon Wiki: Mapping oncological information across the European Union. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 25(1), 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems, 13(3), 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driggin, E., Madhavan, M. V., Bikdeli, B., Chuich, T., Laracy, J., Biondi-Zoccai, G., Brown, T. S., Der Nigoghossian, C., Zidar, D. A., Haythe, J., Brodie, D., Beckman, J. A., Kirtane, A. J., Stone, G. W., Krumholz, H. M., & Parikh, S. A. (2020). Cardiovascular considerations for patients, health care workers, and health systems during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 75(18), 2352–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, C. M., & Jones, N. (2020). Impact of IoT on geriatric telehealth. Working with Older People, 24(3), 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T., Wherton, J., Papoutsi, C., Lynch, J., Hughes, G., Hinder, S., Fahy, N., Procter, R., & Shaw, S. (2017). Beyond adoption: A new framework for theorizing and evaluating nonadoption, abandonment, and challenges to the scale-up, spread, and sustainability of health and care technologies. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(11), e8775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossman, Z., Chodick, G., Reingold, S. M., Chapnick, G., & Ashkenazi, S. (2020). The future of telemedicine visits after COVID-19: Perceptions of primary care pediatricians. Israel Journal of Health Policy Research, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X., Sun, Y., Wang, N., Peng, Z., & Yan, Z. (2013). The dark side of elderly acceptance of preventive mobile health services in China. Electronic Markets, 23(1), 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gücin, N. Ö., & Berk, Ö. S. (2015). Technology acceptance in health care: An integrative review of predictive factors and intervention programs. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 195, 1698–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haimi, M., & Gesser-Edelsburg, A. (2022). Application and implementation of telehealth services designed for the elderly population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Health Informatics Journal, 28(1), 14604582221075560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harst, L., Lantzsch, H., & Scheibe, M. (2019). Theories predicting end-user acceptance of telemedicine use: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(5), e13117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igbaria, M., Parasuraman, S., & Baroudi, J. J. (1996). A motivational model of microcomputer usage. Journal of Management Information Systems, 13(1), 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J. D., Yi, M. Y., & Park, J. S. (2013). An empirical test of three mediation models for the relationship between personal innovativeness and user acceptance of technology. Information and Management, 50(4), 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, C., Sanchez-Vazquez, A., & Ivory, C. (2020). Social, organizational, and technological factors impacting clinicians’ adoption of mobile health tools: Systematic literature review. JMIR MHealth and UHealth, 8(2), e15935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killikelly, C., He, Z., Reeder, C., & Wykes, T. (2017). Improving adherence to web-based and mobile technologies for people with psychosis: Systematic review of new potential predictors of adherence. JMIR MHealth and UHealth, 5(7), e94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuan, P. X., Chan, W. K., Fern Ying, D. K., Rahman, M. A. A., Peariasamy, K. M., Lai, N. M., Mills, N. L., & Anand, A. (2022). Efficacy of telemedicine for the management of cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Digital Health, 4(9), e676–e691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layfield, E., Triantafillou, V., Prasad, A., Deng, J., Shanti, R. M., Newman, J. G., & Rajasekaran, K. (2020). Telemedicine for head and neck ambulatory visits during COVID-19: Evaluating usability and patient satisfaction. Head & Neck, 42(7), 1681–1689. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, J. V., Ratzan, S. C., Palayew, A., Gostin, L. O., Larson, H. J., Rabin, K., Kimball, S., & El-Mohandes, A. (2021). A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nature Medicine, 27(2), 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, B., & Davidovitch, N. (2022). The healthcare system in Israel: An overview. In State of the Nation Report: Society, Economy and Policy. Taub Center for Social Policy Studies in Israel. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, C., Huang, Y.-J., & Hsieh, T.-H. (2016). Factors influencing internet banking adoption. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 44(9), 1443–1455. [Google Scholar]

- Maurer, M. M., & Simonson, M. (1984, February). Development and validation of a measure of computer anxiety [Paper presentation]. Annual Meeting of the Association for Educational Communications and Technology, Dallas, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Oreg, S., Bayazit, M., Vakola, M., Arciniega, L., Armenakis, A., Barkauskiene, R., Bozionelos, N., Fujimoto, Y., González, L., & Han, J. (2008). Dispositional resistance to change: Measurement equivalence and the link to personal values across 17 nations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(4), 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, J. C., & Simpson, D. C. (2022). Telemedicine and health disparities. Clinical Liver Disease, 19(4), 144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabaa’i, A. A. (2016). Extending the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to assess students’ behavioural intentions to adopt an e-learning system: The case of moodle as a learning tool. Journal of Emerging Trends in Engineering and Applied Sciences, 7(1), 13–30. [Google Scholar]

- Rotenberg, D. K., Stewart-Freedman, B., Søgaard, J., Vinker, S., Lahad, A., & Søndergaard, J. (2022). Similarities and differences between two well-performing healthcare systems: A comparison between the Israeli and the Danish healthcare systems. Israel Journal of Health Policy Research, 11(1), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadé, R. G., & Kira, D. (2009). Computer anxiety in e-learning: The effect of computer self-efficacy. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 8(1), 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schepers, J., & Wetzels, M. (2007). A meta-analysis of the technology acceptance model: Investigating subjective norm and moderation effects. Information and Management, 44(1), 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedgwick, P. (2013). Convenience sampling. BMJ, 347, f6304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiferaw, K. B., & Mehari, E. A. (2019). Modeling predictors of acceptance and use of electronic medical record system in a resource limited setting: Using modified UTAUT model. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked, 17, 100182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, D. M., Dishaw, M. T., & Bandy, D. B. (2006). Extending task technology fit with computer self-efficacy. ACM SIGMIS Database: The DATABASE for Advances in Information Systems, 37(2–3), 96–107. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, T., Lin, W., Chang, Y., & Chang, P. (2020). Technology anxiety and resistance to change behavioral study of a wearable cardiac warming system using an extended TAM for older adults. PLoS ONE, 15(1), e0227270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesh, V., & Davis, F. D. (2000). Theoretical extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four longitudinal field studies. Management Science, 46(2), 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems, 27(3), 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y. L., & Xu, X. (2012). Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Quarterly, 36(1), 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verfürth, M. (2020). Design and validation of a questionnaire to measure the Acceptance of Telemedicine by Healthcare Professionals in Germany. Research Square, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2021). Decade of healthy ageing: 2021–2030. Available online: https://www.who.int/initiatives/decade-of-healthy-ageing (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Xue, Y., Liang, H., Mbarika, V., Hauser, R., Schwager, P., & Getahun, M. K. (2015). Investigating the resistance to telemedicine in Ethiopia. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 84(8), 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zander, A. (1950). Resistance to change—Its analysis and prevention. Advanced Management Journal, 15(1), 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zulfiqar, A. A., Hajjam, A., Talha, S., Hajjam, M., Hajjam, J., Ervé, S., & Andrès, E. (2018). Telemedicine and geriatrics in France: Inventory of experiments. Current Gerontology and Geriatrics Research, 2018(1), 9042180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Categories | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Women | 253 | 62.3 |

| Men | 127 | 31.3 | |

| Marital Status | Single | 72 | 17.5 |

| Married/In a relationship | 264 | 65.0 | |

| Divorced | 40 | 9.9 | |

| Widowed | 5 | 1.2 | |

| Level of Religiosity | Secular | 150 | 36.9 |

| Traditional | 133 | 32.8 | |

| Religious | 74 | 18.2 | |

| Very Religious | 9 | 2.2 | |

| Religion | Jewish | 186 | 45.8 |

| Muslim | 156 | 38.4 | |

| Christian | 19 | 4.7 | |

| Druze | 2 | 0.5 | |

| Other/non | 3 | 0.7 | |

| Children | Yes | 272 | 67.0 |

| No | 104 | 25.6 | |

| Number of Children (if any) | 1–2 | 149 | 36.7 |

| 3–4 | 99 | 24.4 | |

| 4 and above | 11 | 2.9 | |

| Job Description | Physician | 42 | 10.3 |

| Nurse | 225 | 55.4 | |

| Social Worker | 13 | 3.2 | |

| Physiotherapist | 32 | 7.9 | |

| Speech Therapist | 11 | 2.7 | |

| Occupational Therapist | 15 | 3.7 | |

| Clinical Dietitian | 12 | 3.0 | |

| Work in Shifts | Morning | 139 | 34.2 |

| Evening/Night Shifts | 222 | 54.7 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Self-efficacy for using telemedicine | 0.857 | ||||||

| 2. Subjective norms towards telemedicine | 0.486 | 0.863 | |||||

| 3. Anxiety about using telemedicine | −0.328 | −0.074 | 0.831 | ||||

| 4. Resistance to technological changes at work | −0.320 | −0.007 | 0.627 | 0.797 | |||

| 5. Perceived usefulness | 0.495 | 0.618 | −0.343 | −0.302 | 0.903 | ||

| 6. Perceived ease of use | 0.633 | 0.569 | −0.367 | −0.328 | 0.722 | 0.867 | |

| 7. Intention to use telemedicine | 0.482 | 0.518 | −0.307 | −0.272 | 0.762 | 0.734 | 0.947 |

| B | SE | LLCI, ULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived usefulness -> intention to use telemedicine | 0.48 | 0.06 | 0.35, 0.61 |

| Perceived ease of use -> intention to use telemedicine | 0.46 | 0.08 | 0.30, 0.63 |

| Perceived ease of use -> perceived usefulness | 0.61 | 0.08 | 0.44, 0.78 |

| Self-efficacy for using telemedicine -> perceived usefulness | −0.04 | 0.05 | −0.14, 0.05 |

| Subjective norms towards telemedicine -> perceived usefulness | 0.37 | 0.06 | 0.24, 0.51 |

| Anxiety about using telemedicine -> perceived usefulness | −0.08 | 0.04 | −0.17, 0.01 |

| Resistance to technological changes at work -> perceived usefulness | −0.11 | 0.07 | −0.26, 0.02 |

| Self-efficacy for using telemedicine -> perceived ease of use | 0.29 | 0.05 | 0.18, 0.39 |

| Subjective norms towards telemedicine -> perceived ease of use | 0.34 | 0.05 | 0.24, 0.45 |

| Anxiety about using telemedicine -> perceived ease of use | −0.10 | 0.05 | −0.212, 0.00 |

| Resistance to technological changes at work -> perceived ease of use | −0.12 | 0.07 | −0.26, 0.01 |

| Self-efficacy for using telemedicine -> perceived ease of use -> perceived usefulness | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.09, 0.25 |

| Subjective norms towards telemedicine -> perceived ease of use -> perceived usefulness | 0.21 | 0.03 | 0.14, 0.28 |

| Anxiety about using telemedicine -> perceived ease of use -> perceived usefulness | −0.06 | 0.03 | −0.13, 0.00 |

| Resistance to technological changes at work -> perceived ease of use -> perceived usefulness | −0.07 | 0.04 | −0.163, 0.01 |

| perceived ease of use -> perceived usefulness -> intention to use telemedicine | 0.29 | 0.05 | 0.19, 0.39 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Porat-Packer, T.; Green, G.; Sharon, C.; Tesler, R. Factors Influencing Telemedicine Adoption Among Healthcare Professionals in Geriatric Medical Centers: A Technology Acceptance Model Approach. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1367. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101367

Porat-Packer T, Green G, Sharon C, Tesler R. Factors Influencing Telemedicine Adoption Among Healthcare Professionals in Geriatric Medical Centers: A Technology Acceptance Model Approach. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1367. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101367

Chicago/Turabian StylePorat-Packer, Tammy, Gizell Green, Cochava Sharon, and Riki Tesler. 2025. "Factors Influencing Telemedicine Adoption Among Healthcare Professionals in Geriatric Medical Centers: A Technology Acceptance Model Approach" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1367. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101367

APA StylePorat-Packer, T., Green, G., Sharon, C., & Tesler, R. (2025). Factors Influencing Telemedicine Adoption Among Healthcare Professionals in Geriatric Medical Centers: A Technology Acceptance Model Approach. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1367. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101367