Correcting a Longstanding Misconception about Social Roles and Personality: A Case Study in the Psychology of Science

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Famous but Incorrect Fels Interpretation of Sex Differences in Personality Stability

2.1. Historical Significance of the Fels Study

2.2. The Fels Interpretation of Sex Differences in Personality Stability

“Passive and dependent behavior are subjected to consistent cultural disapproval for men but not for women. … It is not surprising, therefore, that childhood passivity and dependency were related to adult passive and dependent behavior for women, but not for men” [12] (p. 268) and “the individual’s desire to mold his overt behavior in concordance with the culture’s definition of sex-appropriate responses is a major determinant of the patterns of continuity and discontinuity in his development”.[12] (p. 269)

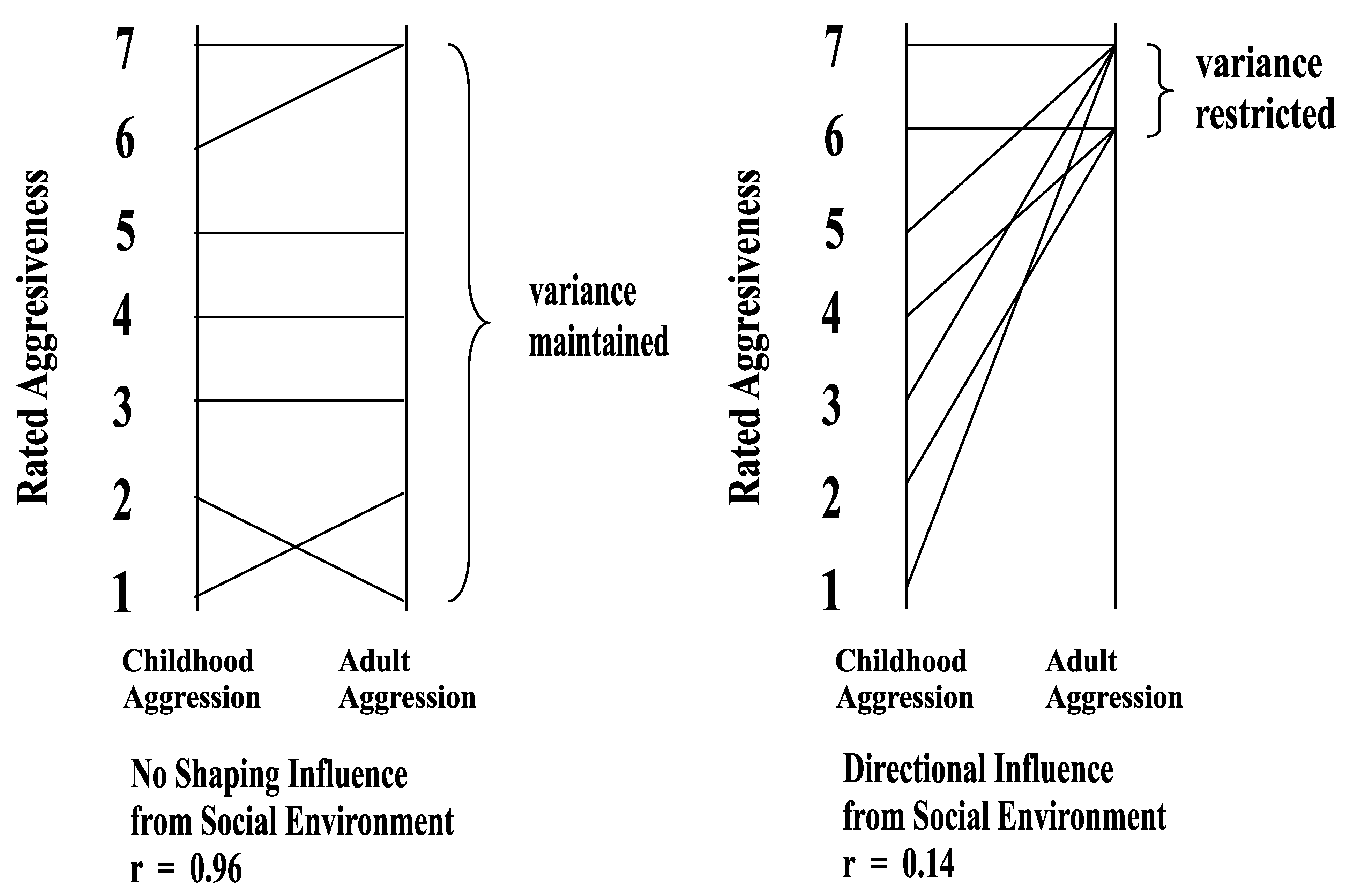

2.3. Why the Fels Conclusion Is a Misinterpretation of the Data

3. Why Did Kagan and Moss Get It Wrong?

Theory-Laden Confusion of the Two Meanings of Stability

4. The Promulgation of the Erroneous Fels Conclusion

4.1. The Staying Power of the Erroneous Fels Conclusion

4.2. Failure of the Fels Finding to Replicate

4.3. Desire for Freedom as a Motive for Continued Acceptance of the Kagan-Moss Misinterpretation

4.4. Social Constructivists’ Political Arguments against Biology

5. Conclusions: The Truth about Biological Stability and Change

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Simon, P. The boxer. In Bridge over Troubled Waters; [vinyl record]; Columbia: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Kunda, Z. The case for motivated reasoning. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 108, 480–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruner, J.S. Personality dynamics and the process of perceiving. In Perception—An Approach to Personality; Blake, R., Ramsy, G.V., Eds.; Ronald Press: New York, NY, USA, 1951; pp. 94–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hastorf, A.H.; Cantril, H. They saw a game; a case study. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psych. 1954, 49, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, J.S.; Postman, L. On the perception of incongruity: A paradigm. J. Pers. 1949, 18, 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allport, G.W. Personality: A Psychological Interpretation; Holt, Rinehart and Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1937; ASIN B0006D662C. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, J.S.; Goodman, C.C. Value and need as organizing factors in perception. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psych. 1947, 42, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitayama, S.; Duffy, S.; Kawamura, T.; Larsen, J.T. Perceiving an object and its context in different cultures: A cultural look at the New Look. Psychol. Sci. 2003, 14, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, N.R. Patterns of Discovery: An Inquiry into the Conceptual Foundations of Science; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1958; ISBN 978-0-521-05197-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, T.S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, 1st ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1962; LCCN 62019621. [Google Scholar]

- Shadish, W.R.; Fuller, S.; Gorman, M.E.; Amabile, T.; Kruglanski, A.; Rosenthal, R.; Rosenwein, R.E. Social psychology of science: A conceptual and empirical research program. In Social Psychology of Science; Shadish, W.R., Fuller, S., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 3–123. ISBN 978-0-898-62021-4. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan, J.; Moss, H.A. Birth to Maturity: A Study in Psychological Development, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Block, J. Lives through Time; Bancroft Books: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer, D.R. Developmental Psychology: Childhood and Adolescence, 4th ed.; Thomson Brooks/Cole: Belmont, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lueptow, L.B.; Garovich, L.; Lueptow, M.B. The persistence of gender stereotypes in the face of changing sex roles: Evidence contrary to the sociocultural model. Ethol. Sociobiol. 1991, 16, 509–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggins, J.S. Agency and communion as conceptual coordinates for the understanding and measurement of interpersonal behavior. In Thinking Clearly about Psychology: Essays in Honor of Paul E. Meehl; Grove, W., Cicchetti, D., Eds.; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1991; Volume 2, pp. 89–113. ISBN 978-0-816-61918-4. [Google Scholar]

- McNemar, W. Psychological Statistics, 4th ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1969; ISBN 978-0-471-58708-8. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, P.T., Jr.; McCrae, R.R. Longitudinal stability of adult personality. In Handbook of Personality Psychology; Hogan, R., Johnson, J., Briggs, S.R., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1997; pp. 269–290. ISBN 978-0-121-34646-1. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social learning through imitation. In Nebraska Symposium on Motivation; Jones, M.R., Ed.; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 1962; pp. 211–274. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A.; Walters, R.H. Adolescent Aggression; Ronald Press: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A.; Walters, R.H. Social Learning and Personality Development; Holt, Rinehart & Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, R.M.; Hultsch, D.F. Human Development: A Life-Span Perspective; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald, J.M. Lifespan Human Development; Wadsworth: Belmont, CA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Santrock, J.W.; Bartlett, J.C. Developmental Psychology: A Life-Cycle Perspective; Wm. C. Brown: DuBuque, IA, USA, 1986; ISBN 978-0-697-00719-3. [Google Scholar]

- Sigelman, C.K.; Shaffer, D.R. Life-Span Human Development; Brooks/Cole: Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 1991; ISBN 978-0-534-12282-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hetheringon, E.M.; Parke, R.D. Child Psychology: A Contemporary Viewpoint, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill: Boston, MA, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0-072-82014-0. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, J. Sex differences in social behavior: Are the social role and evolutionary explanations compatible? Am. Psychol. 1996, 51, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parke, R.D.; Slaby, R.G. The development of aggression. In Handbook of Child Psychology, 4th ed.; Mussen, P.H., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1983; Volume 4, pp. 547–642. ISBN 978-0-471-05194-7. [Google Scholar]

- Thagard, P. The passionate scientist: Emotion in scientific cognition. In The Cognitive Basis of Science; Carruthers, P., Stich, S., Siegal, M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002; pp. 235–250. ISBN 978-0-521-01177-8. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.A.; Germer, C.K.; Efran, J.S.; Overton, W.F. Personality as the basis for theoretical predilections. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 55, 824–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eagly, A.H. Bridging the gap between gender politics and the science of gender. Psychol. Inq. 1994, 5, 83–85. [Google Scholar]

- Eagly, A.H. The science and politics of comparing women and men. Am. Psychol. 1995, 50, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, R.K. Sex, gender, and epistemology. In Gender and Thought: Psychological Perspectives; Crawford, M., Gentry, M., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: New York, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 17–35. ISBN 978-1-4612-8168-9. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae, R.R.; Costa, P.T., Jr. The stability of personality: Observations and evaluations. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1994, 3, 173–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mischel, W. On the interface of cognition and personality: Beyond the person-situation debate. Am. Psychol. 1979, 34, 740–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mischel, W. Convergences and challenges in the search for consistency. Am. Psychol. 1984, 39, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.A. Some Hypotheses Concerning Attempts to Separate Situations from Personality Dispositions. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Personality Traits and Situations, de Raad, B. (Chair). 6th European Congress of Psychology, Rome, Italy, 7 July 1999; Available online: http://www.personal.psu.edu/~j5j/papers/ConferencePapers/1999ECP.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2018).

- Kenrick, D.T.; Funder, D. Profiting from controversy: Lessons from the person-situation debate. Am. Psychol. 1988, 43, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, J.A. Wrong and right questions about persons and situations. J. Res. Pers. 2009, 43, 251–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mischel, W. A social-learning view of sex differences in behavior. In The Development of Sex Differences; Maccoby, E.E., Ed.; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1966; pp. 56–81. ISBN 978-0-8047-0308-6. [Google Scholar]

- Mischel, W. Toward a cognitive social learning theory reconceptualization of personality. Psychol. Rev. 1973, 80, 252–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantor, N.; Mischel, W. Prototypicality and personality: Effects on free recall and personality impressions. J. Res. Pers. 1979, 13, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H.; Crane, M.; Bernstein, S.; Siladi, M. Self-schemas and gender. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1982, 42, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H.; Smith, J. The influence of self-schemata on the perception of others. In Personality, Cognition, and Social Interaction; Cantor, N., Kihlstrom, J.F., Eds.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1981; pp. 233–262. ISBN 978-0-8985-9057-9. [Google Scholar]

- Marecek, J. Gender, politics, and psychology’s ways of knowing. Am. Psychol. 1995, 50, 162–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruble, D.N.; Martin, C.L. Gender development. In Handbook of Child Psychology, 5th ed.; Damon, W., Eisenberg, N., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2000; Volume 3, pp. 933–1014. ISBN 978-0-4713-4981-5. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E.O. Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge; Alfred A. Knopf: New York, NY, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0-6794-5077-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, R.; Emler, N.P. The biases in contemporary social psychology. Soc. Res. 1978, 45, 478–534. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, R.; Schroeder, D. Seven biases in psychology. Psychol. Today 1981, 15, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, B.D. The moralistic fallacy. Nature 1970, 272, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, C. Evolutionary psychology: Counting babies or studying information-processing mechanisms. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2000, 907, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, B. Moralistic Fallacy. Available online: https://www.logicallyfallacious.com/tools/lp/Bo/LogicalFallacies/128/Moralistic-Fallacy (accessed on 11 May 2018).

- Horgan, J. Darwin was Sexist, and so are Many Modern Scientists. [Sci. Am. blog post], 18 December 2017. Available online: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/cross-check/darwin-was-sexist-and-so-are-many-modern-scientists/# (accessed on 14 May 2018).

- Harris, J.R. The Nurture Assumption: Why Children Turn Out the Way They Do; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0-684-84409-1. [Google Scholar]

- Begley, S. The parent trap. Newsweek 1998, 132, 52–59. [Google Scholar]

- Atwood, G.E.; Tomkins, S.S. On the subjectivity of personality theory. J. Hist. Behav. Sci. 1976, 12, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coan, R.W. Psychologists: Personal and Theoretical Pathways; Irvington: New York, NY, USA, 1979; ISBN 978-0-4702-6785-1. [Google Scholar]

- Conway, J.B. A world of differences among psychologists. Can. Psychol. 1992, 33, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elms, A.C. Allport’s personality and Allport’s personality. In Fifty Years of Personality Psychology; Craik, K.H., Hogan, R., Wolfe, R.N., Eds.; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 39–55. ISBN 978-1-4899-2311-0_3. [Google Scholar]

- Feist, G.J.; Gorman, M.E. The psychology of science: Review and integration of a nascent discipline. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1998, 2, 3–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, J.J. Psychology of the scientist: XLVI: Correlation between theoretical orientation in psychology and personality type. Psychol. Rep. 1982, 50, 795–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasner, L.; Houts, A.C. A study of the “value” systems of behavioral scientists. Am. Psychol. 1984, 39, 840–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, B.G. Toward a psychology of science. Am. Psychol. 1971, 26, 1010–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCain, G.; Segal, E.M. The Game of Science, 5th ed.; Brooks/Cole: Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 1988; ISBN 978-0-5340-9072-2. [Google Scholar]

- Pinker, S. The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature; Viking: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-0-6700-3151-1. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, D.C. Genetics, temperament, and personality. In Handbook of Personality Psychology; Hogan, R., Johnson, J., Briggs, S.R., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1997; pp. 367–386. [Google Scholar]

- Geary, D.C. Male, Female: The Evolution of Human Sex Differences; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-1-4338-0682-7. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyenga, K.B.; Hoyenga, K.T. Gender Related Differences: Origins and Outcomes; Allyn & Bacon: Needham Heights, MA, USA, 1993; ISBN 978-0-2051-4084-8. [Google Scholar]

- Lippa, R.A. Gender, Nature, and Nurture, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-0-8058-5345-2. [Google Scholar]

- Lippa, R.A.; Hershberger, S.L. Genetic and environmental influences on individual differences in masculinity, femininity, and gender diagnosticity: Analyzing data from a classic twin study. J. Pers. 1999, 67, 127–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DilLalla, L.F.; Kagan, J.; Reznick, J.S. Genetic etiology of behavioral inhibition among 2-year-old children. Infant Behav. Dev. 1994, 17, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, J.; Reznick, J.S.; Clarke, C.; Snidman, N.; Garcia-Coll, C. Behavioral inhibition to the unfamiliar. Child Dev. 1984, 55, 2212–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, J.; Snidman, N. Infant predictors of inhibited and uninhibited behavioral profiles. Psychol. Sci. 1991, 2, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.T., Jr.; Terracciano, A.; McCrae, R.R. Gender differences in personality traits across cultures: Robust and surprising findings. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 81, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, B.P.; Duberstein, P.R.; Sörensen, S.; Lyness, J.M. Gender differences in five factor model personality traits in an elderly cohort: Extension of robust and surprising findings to an older generation. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2007, 43, 1594–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, D.P.; Realo, A.; Voracek, M.; Allik, J. Why can’t a man be more like a woman? Sex differences in big five personality traits across 55 cultures. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 94, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kajonius, P.J.; Johnson, J. Sex differences in 30 facets of the Five Factor Model of personality in the large public (N = 320,128). Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2018, 43, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.A. Preferences Underlying Women’s Choices in Academic Economics. Econ. J. Watch. 2008, 5, 219–226. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, B.W.; DelVecchio, W.F. The rank-order consistency of personality traits from childhood to old age: A quantitative review of longitudinal studies. Psychol. Bull. 2000, 126, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, B.W.; Walton, K.E.; Viechtbauer, W. Patterns of mean-level change in personality traits across the life course: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 132, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buss, D.M. Psychological sex differences: Origins through sexual selection. Am. Psychol. 1995, 50, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Johnson, J.A. Correcting a Longstanding Misconception about Social Roles and Personality: A Case Study in the Psychology of Science. Behav. Sci. 2018, 8, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs8060057

Johnson JA. Correcting a Longstanding Misconception about Social Roles and Personality: A Case Study in the Psychology of Science. Behavioral Sciences. 2018; 8(6):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs8060057

Chicago/Turabian StyleJohnson, John A. 2018. "Correcting a Longstanding Misconception about Social Roles and Personality: A Case Study in the Psychology of Science" Behavioral Sciences 8, no. 6: 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs8060057

APA StyleJohnson, J. A. (2018). Correcting a Longstanding Misconception about Social Roles and Personality: A Case Study in the Psychology of Science. Behavioral Sciences, 8(6), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs8060057