Cognitive Remediation Therapy for Adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa—Treatment Satisfaction and the Perception of Change

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. The Intervention—Cognitive Remediation Therapy

2.4. Assessment—The CRT Treatment Evaluation Questionnaire

2.5. Analyses

3. Results

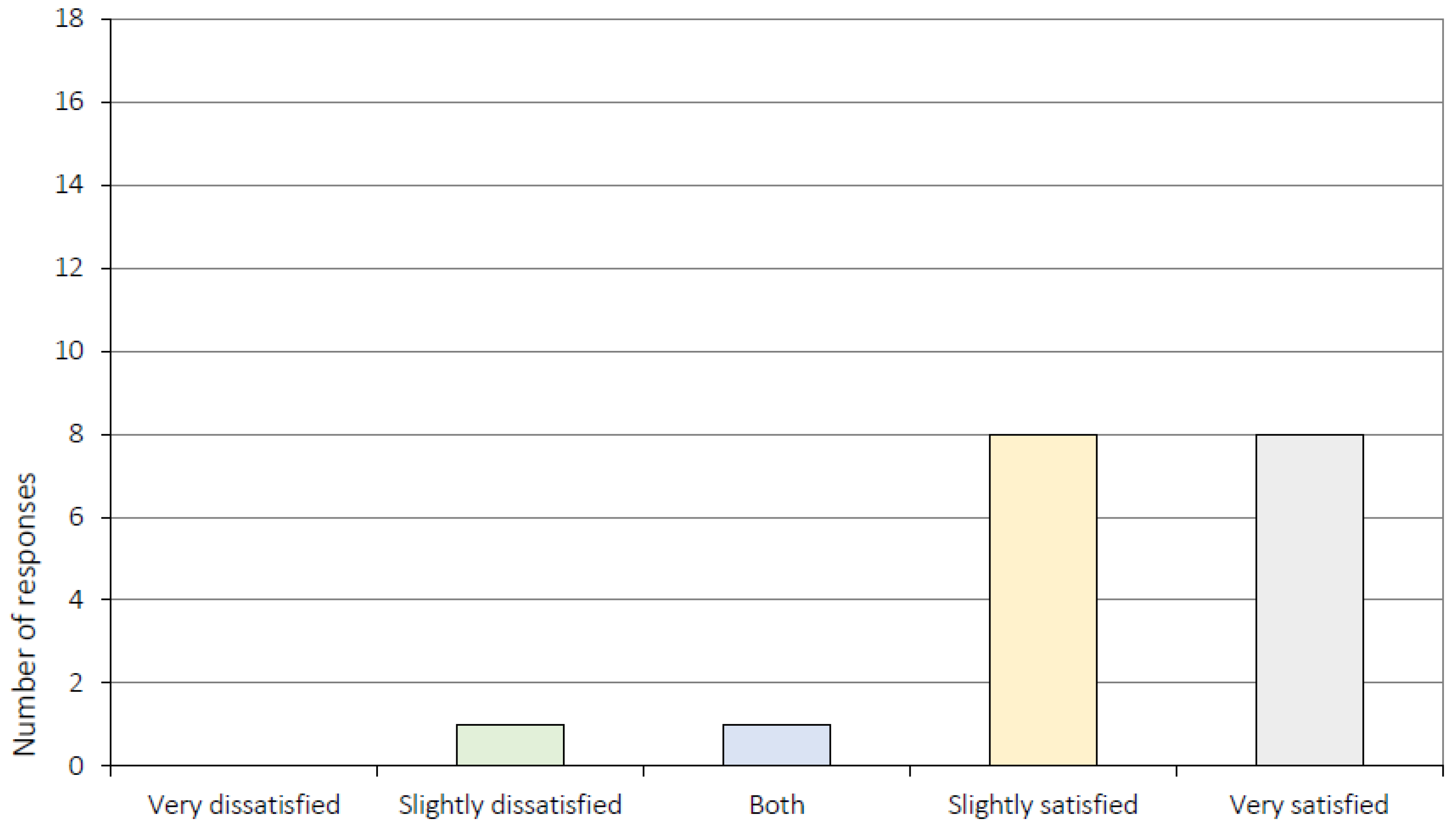

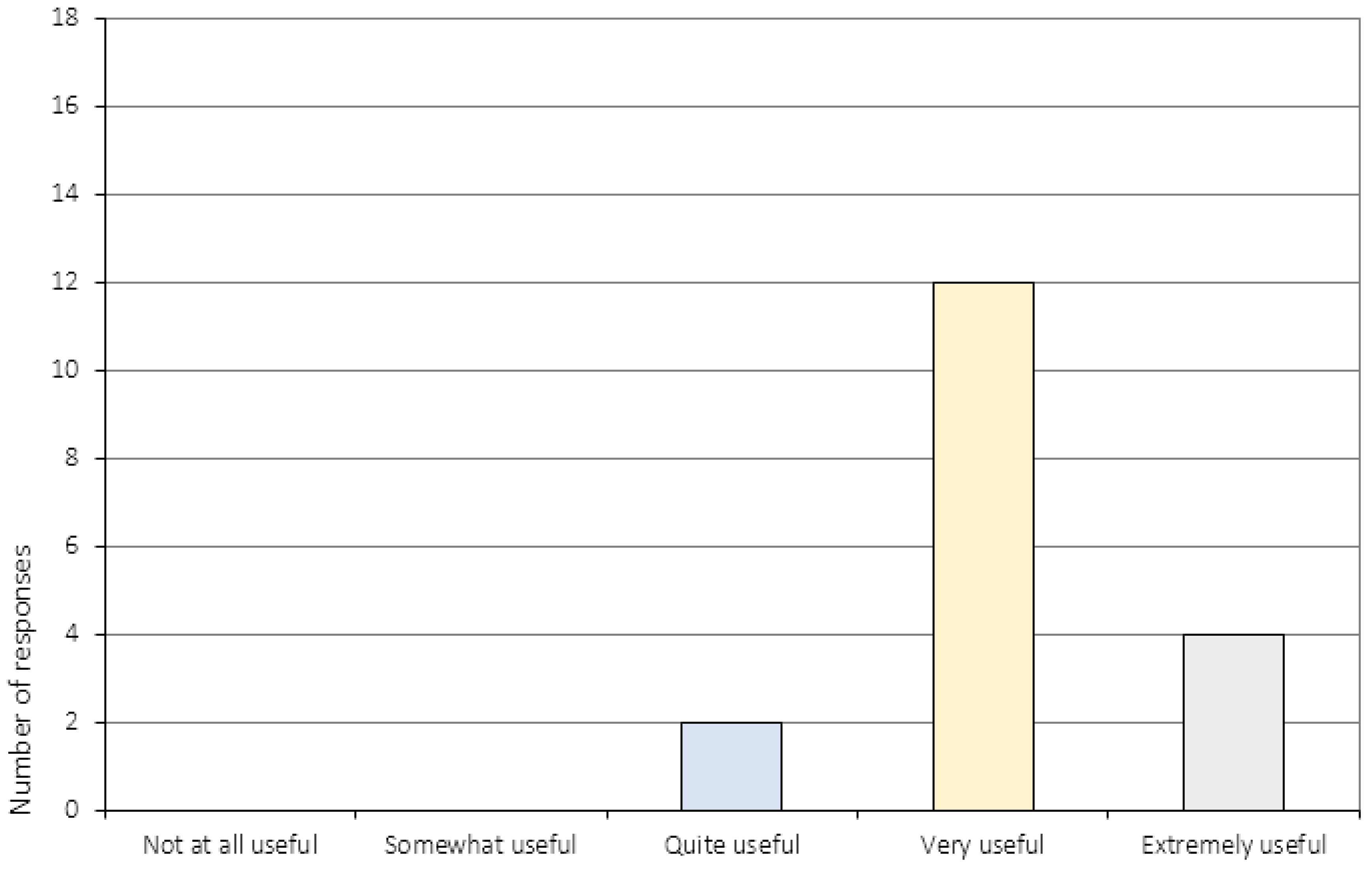

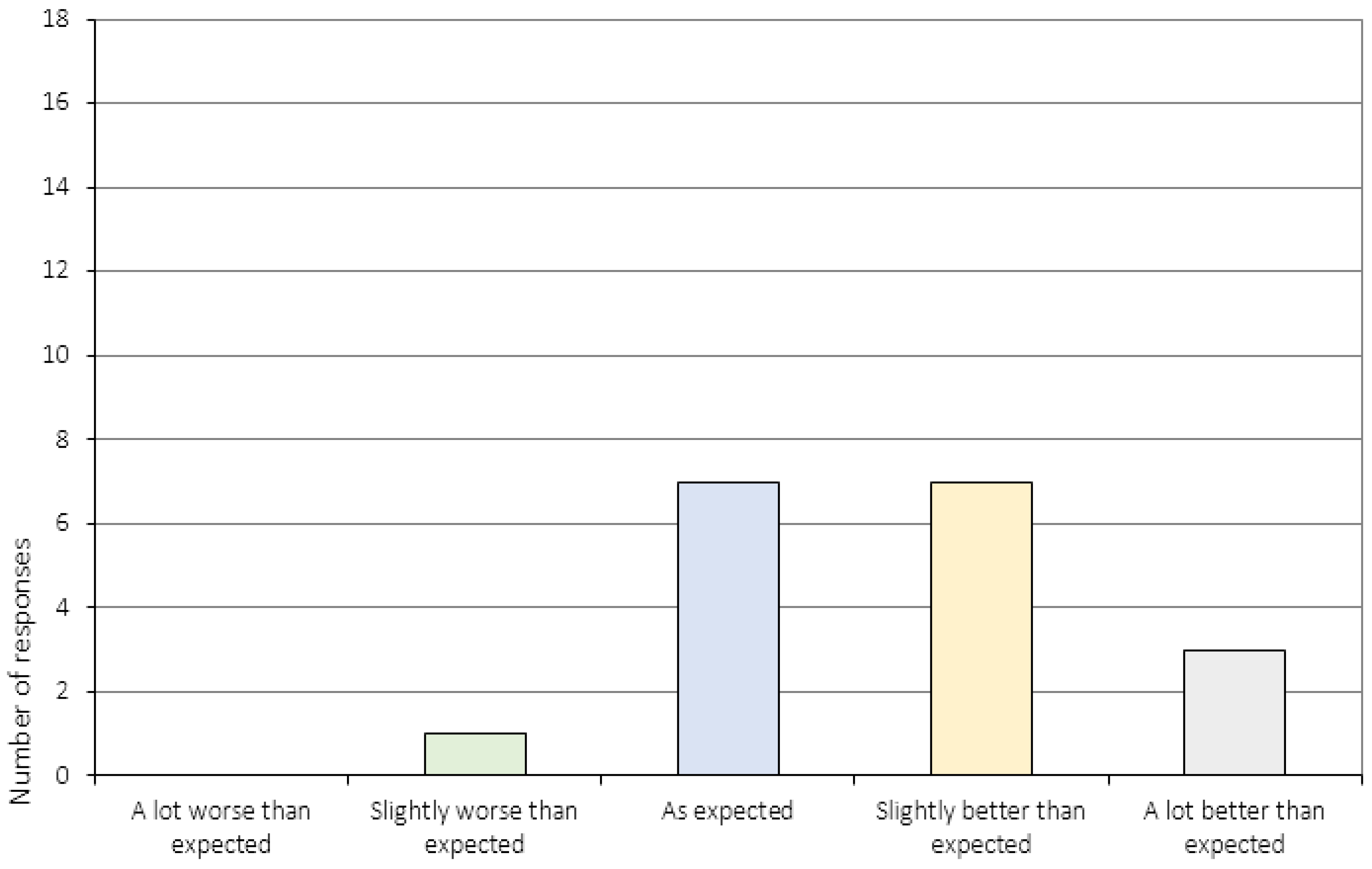

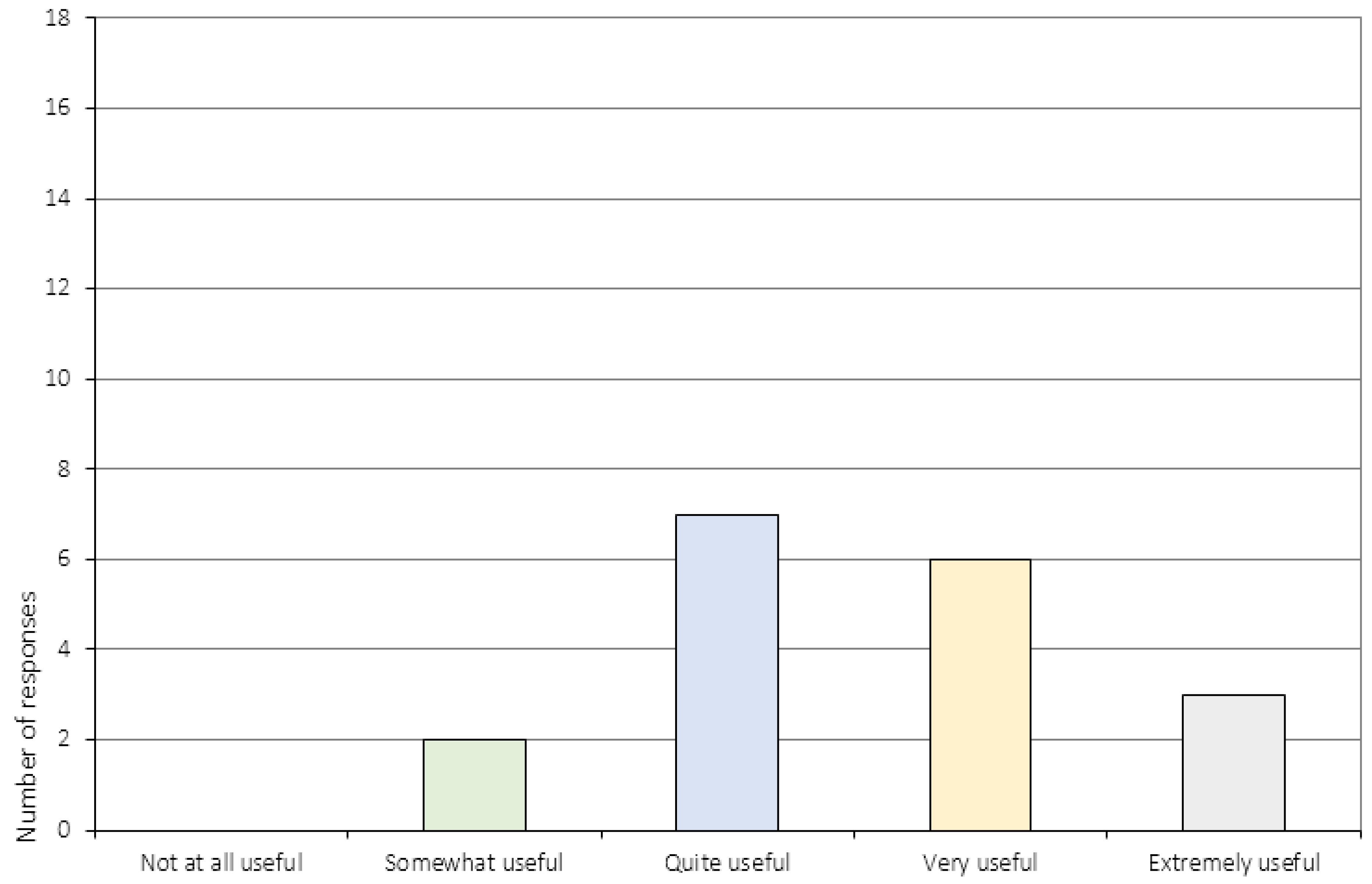

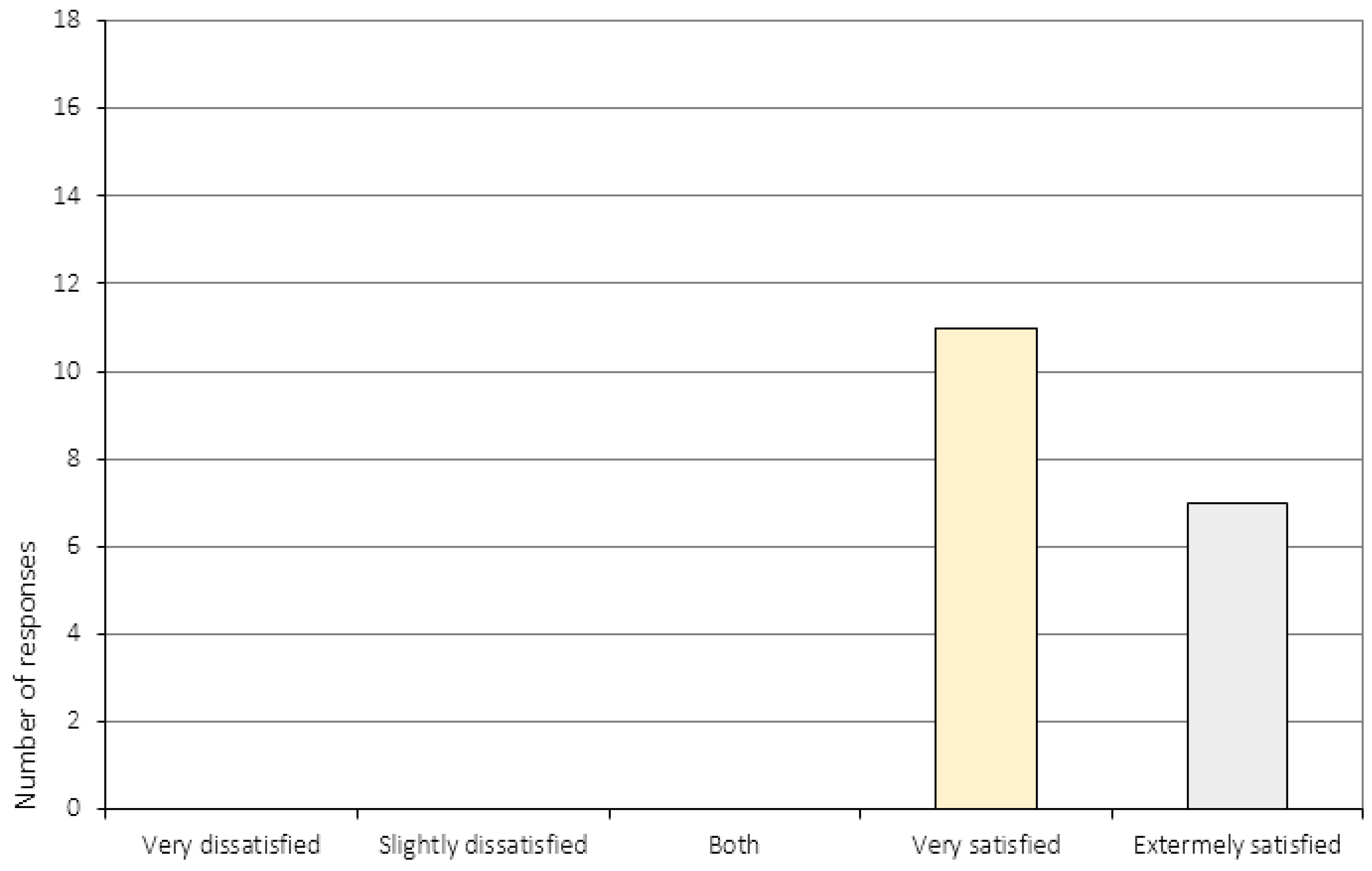

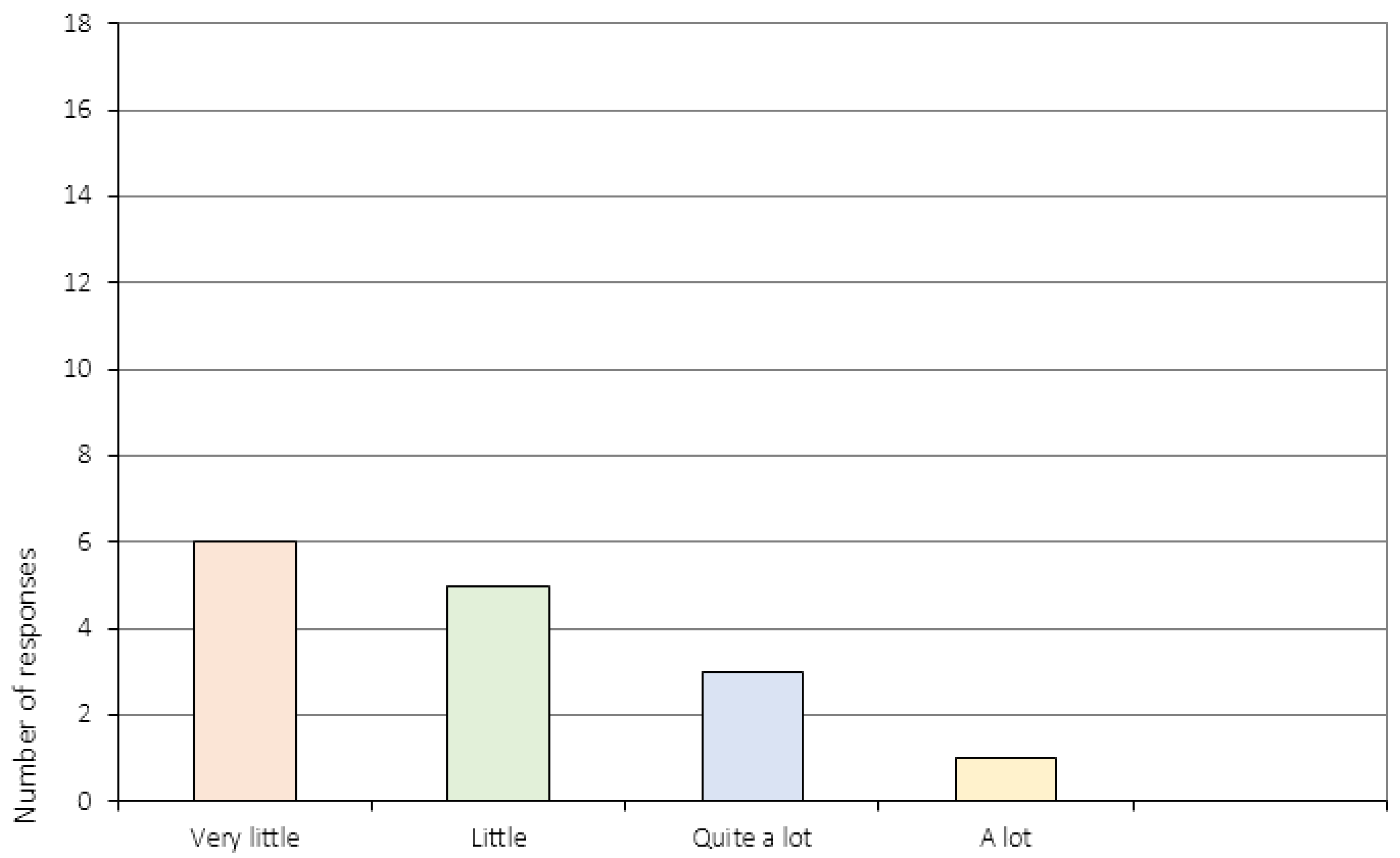

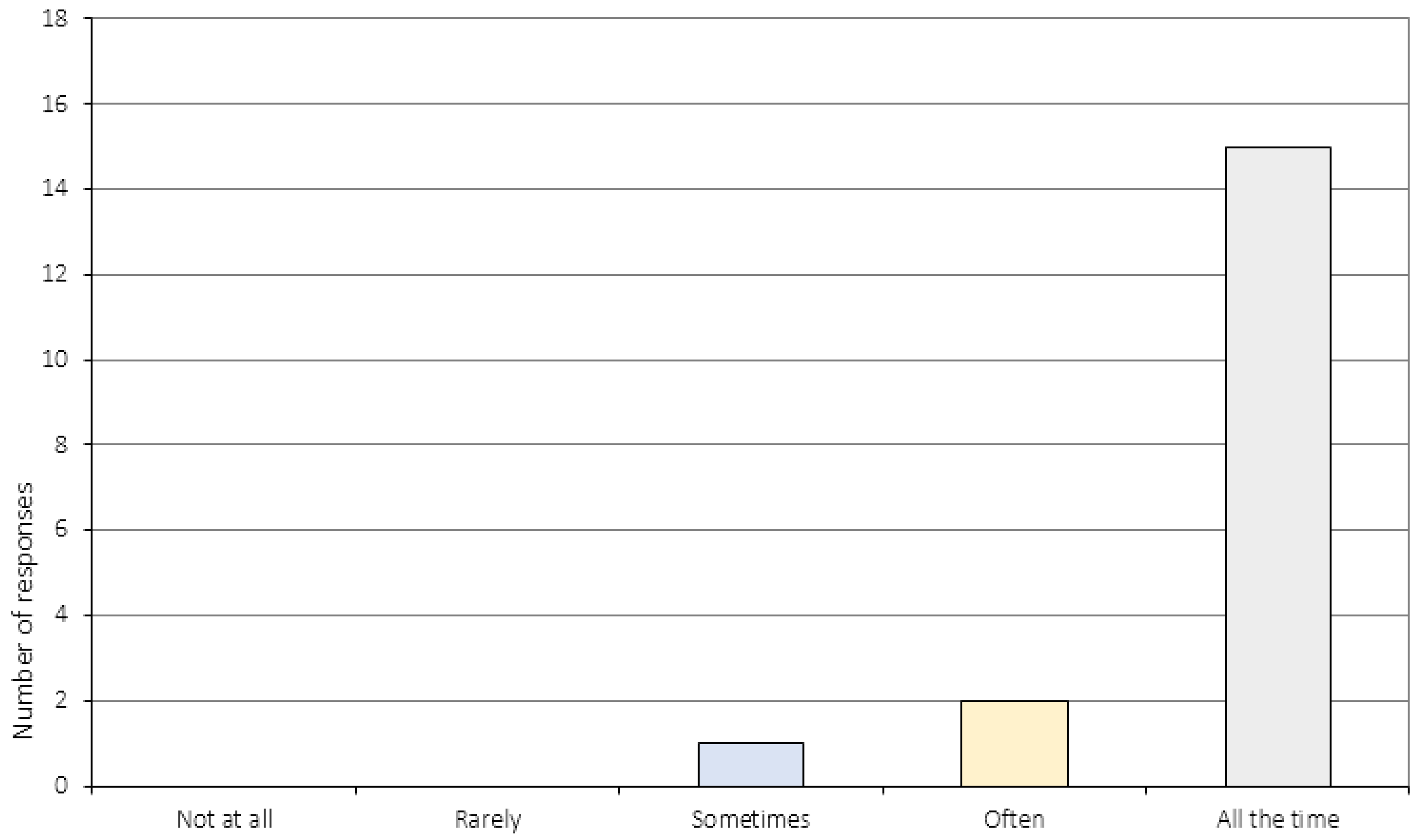

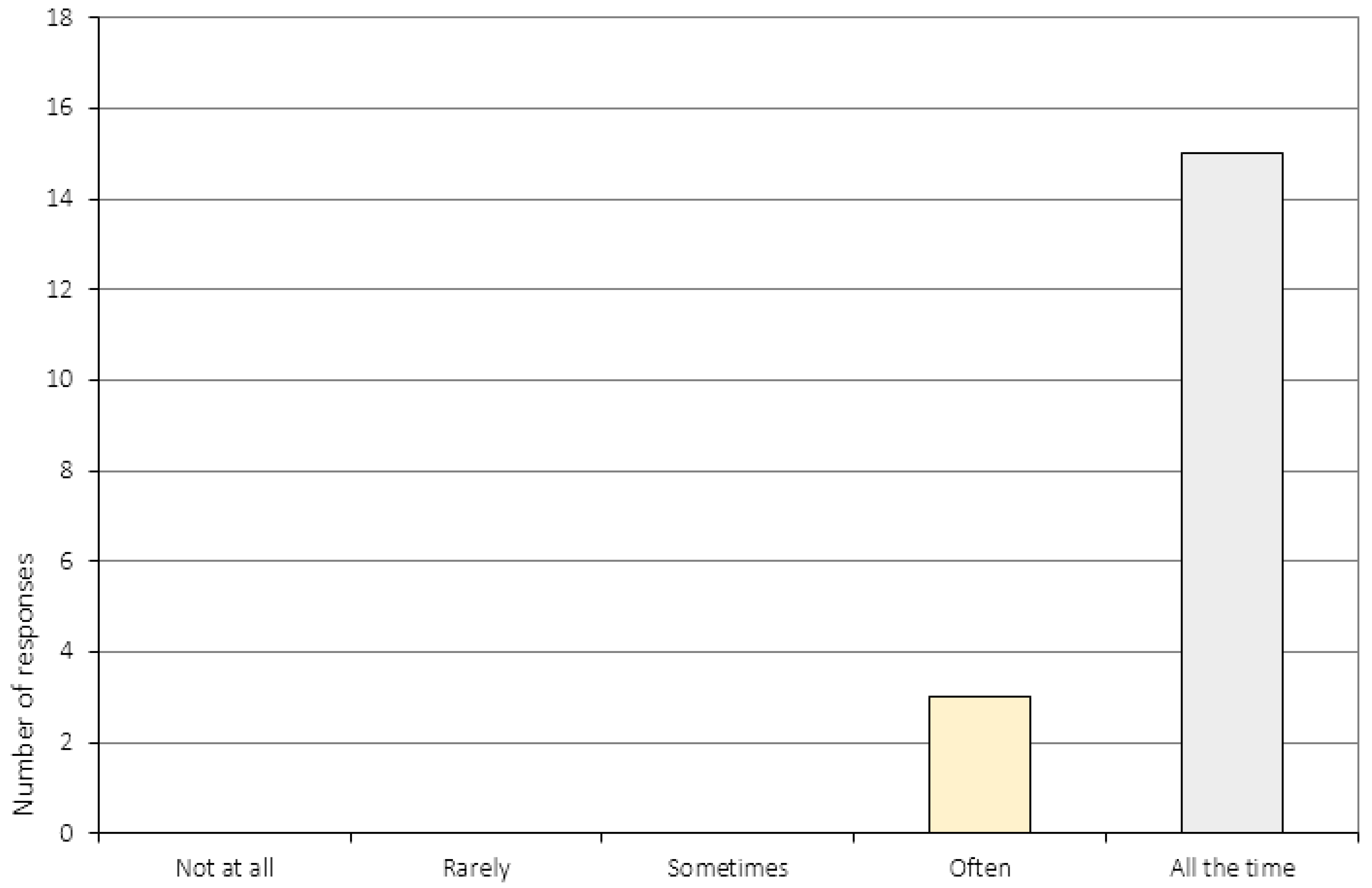

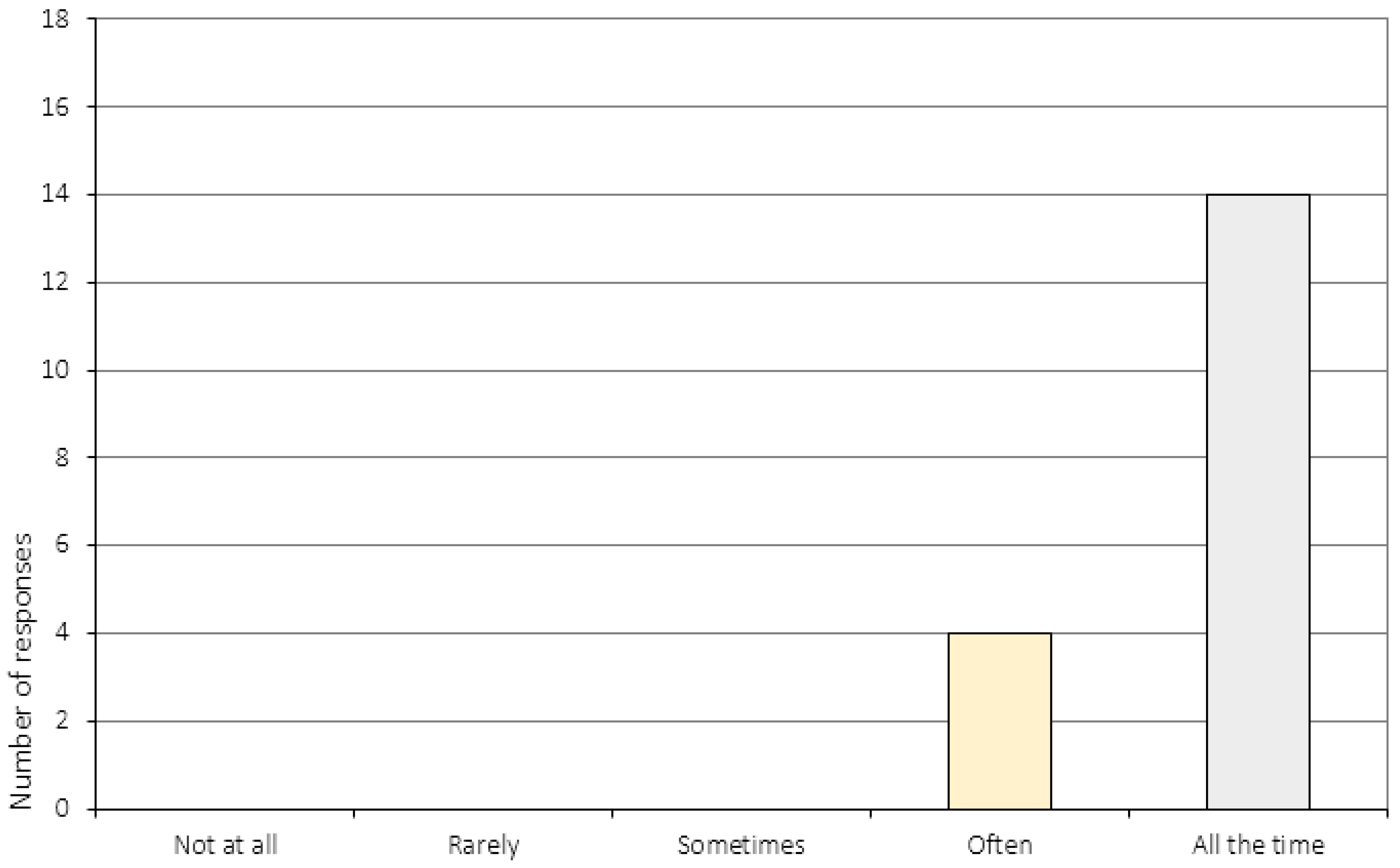

3.1. Treatment Satisfaction

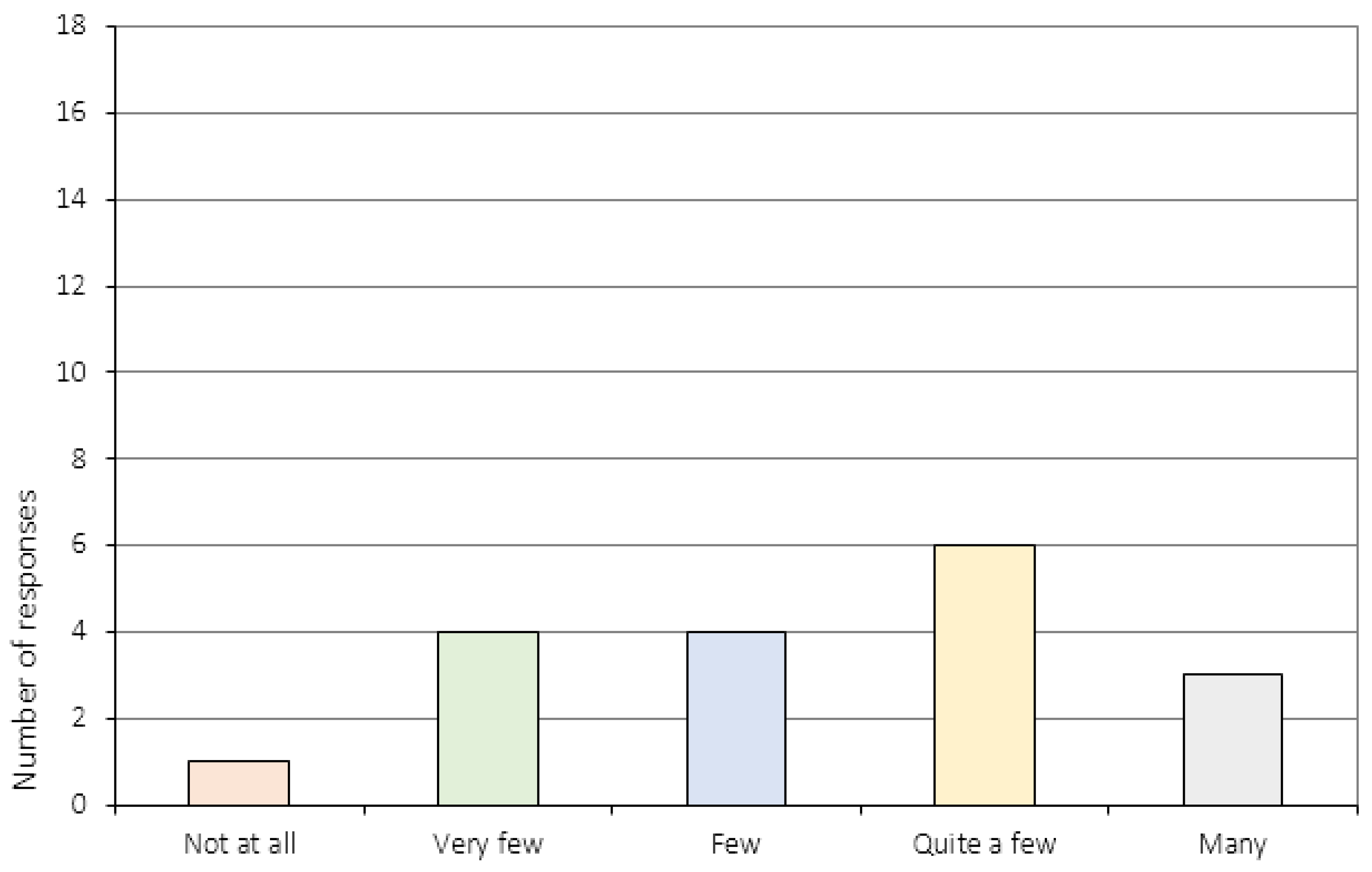

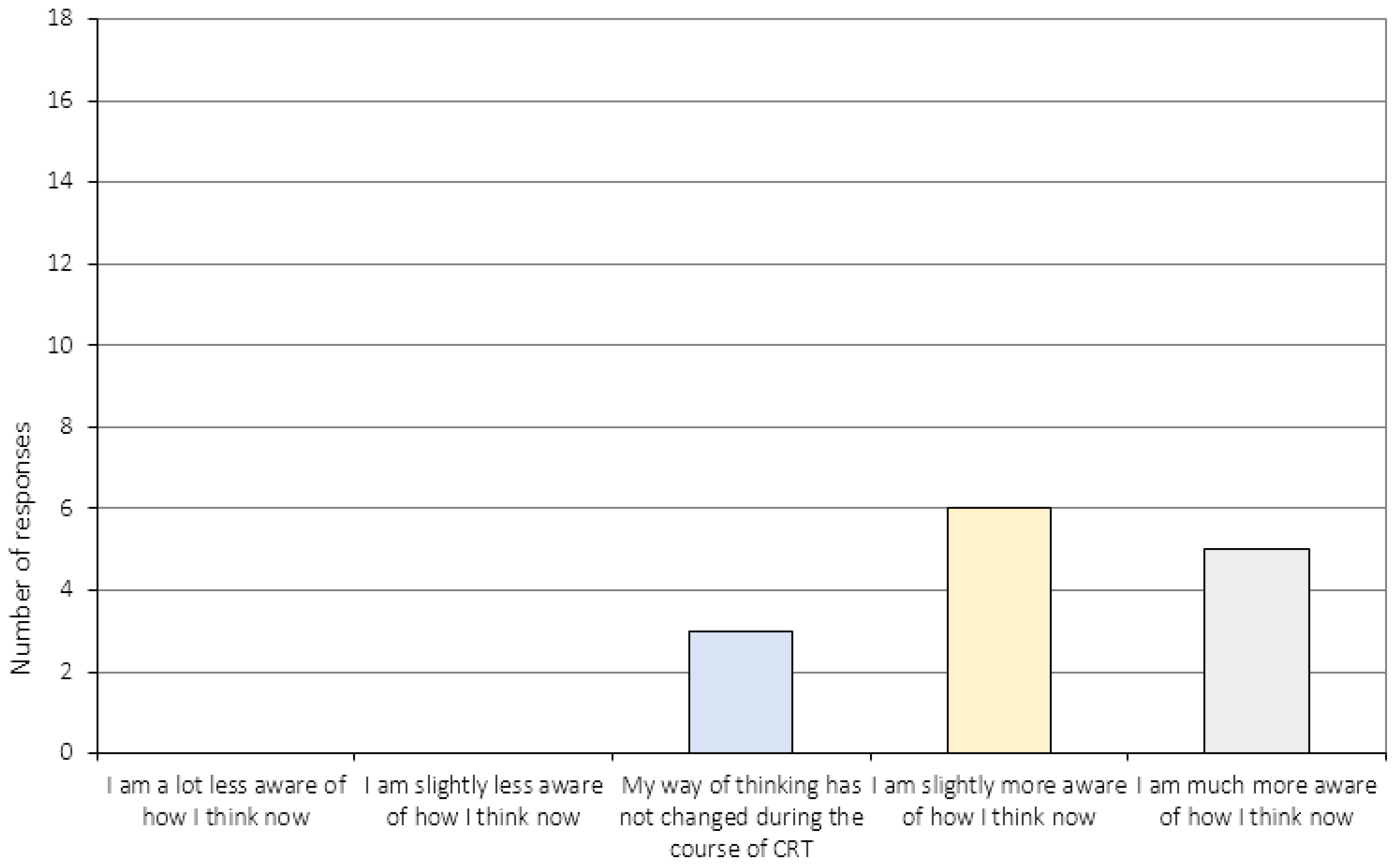

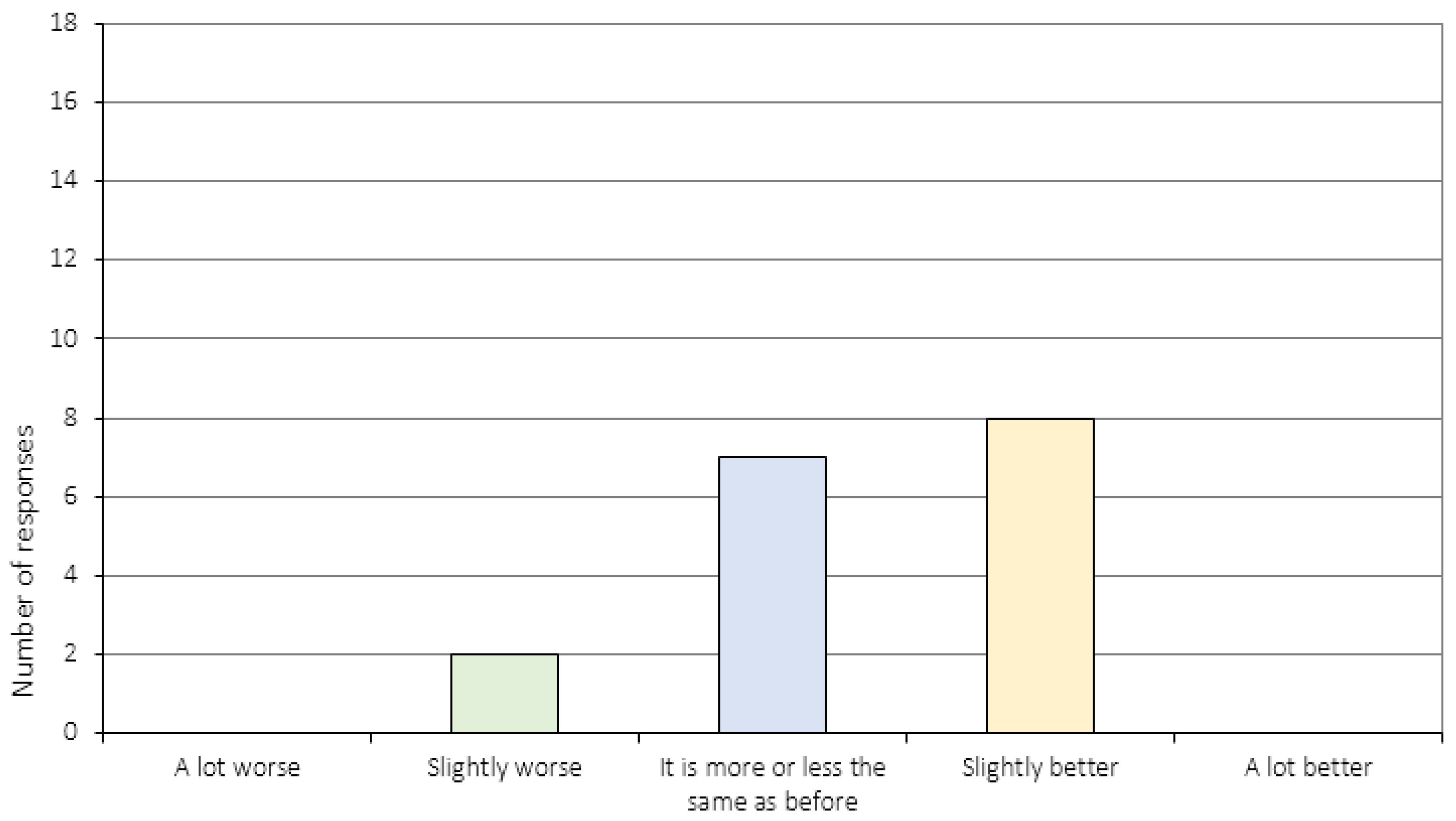

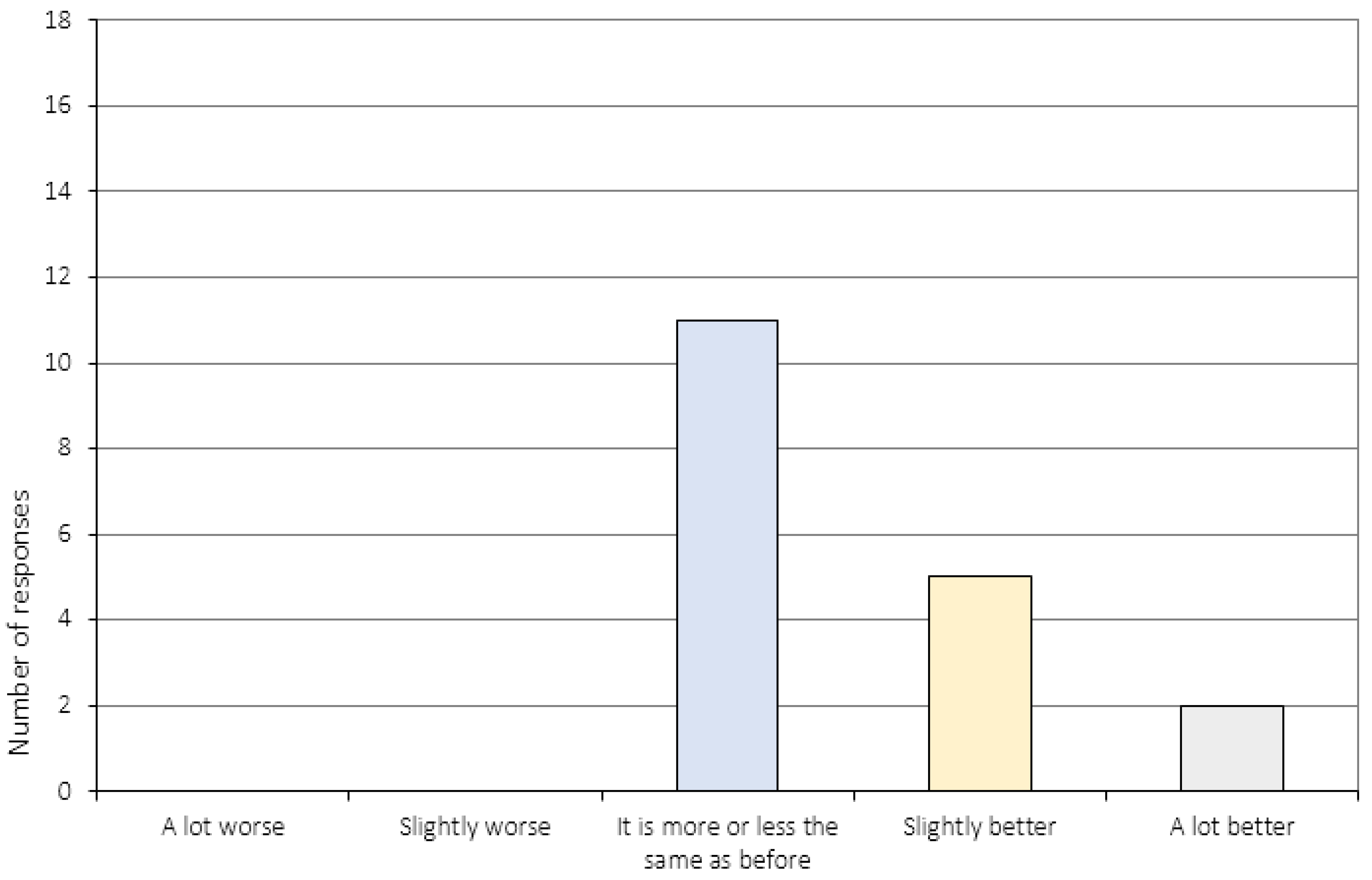

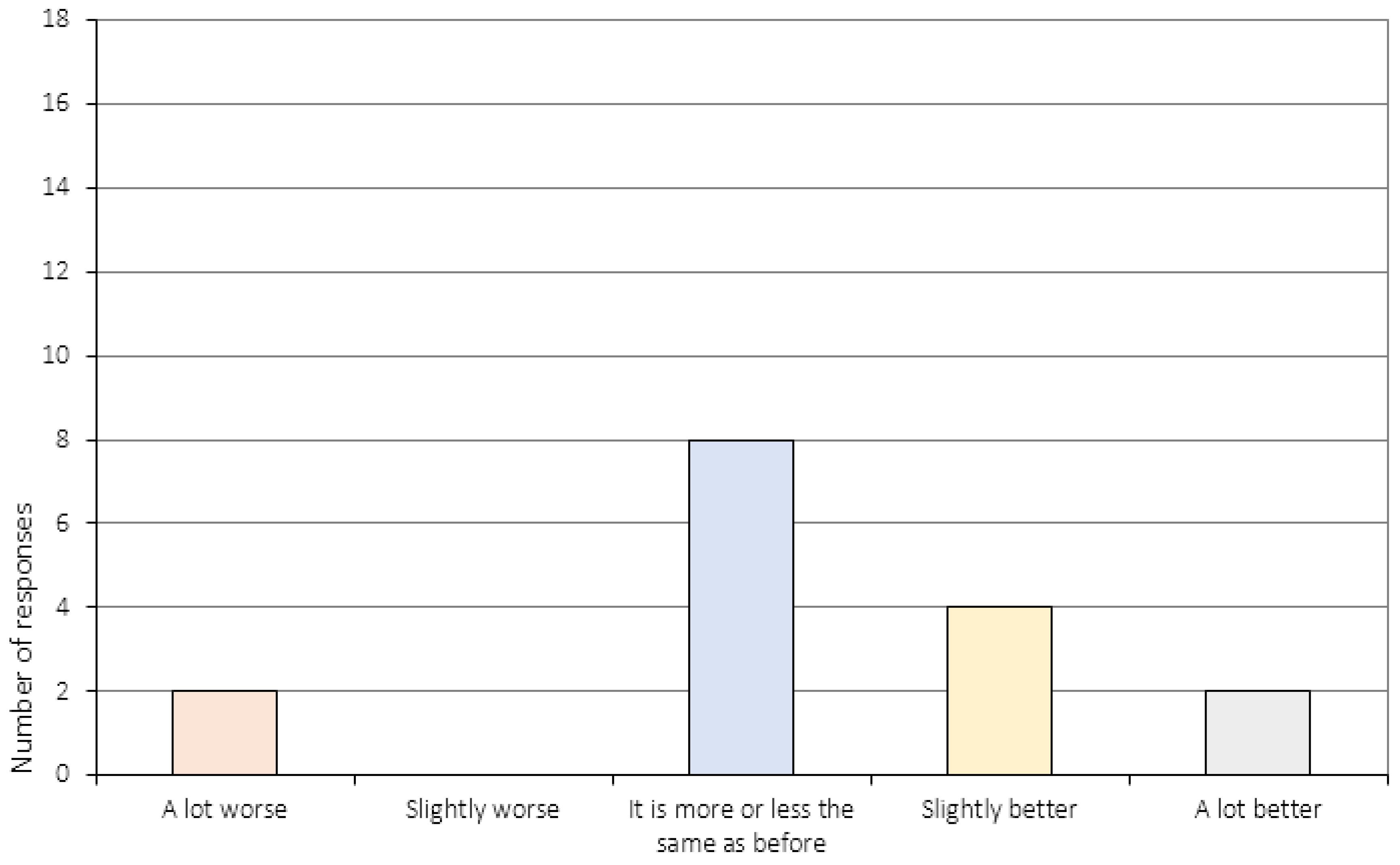

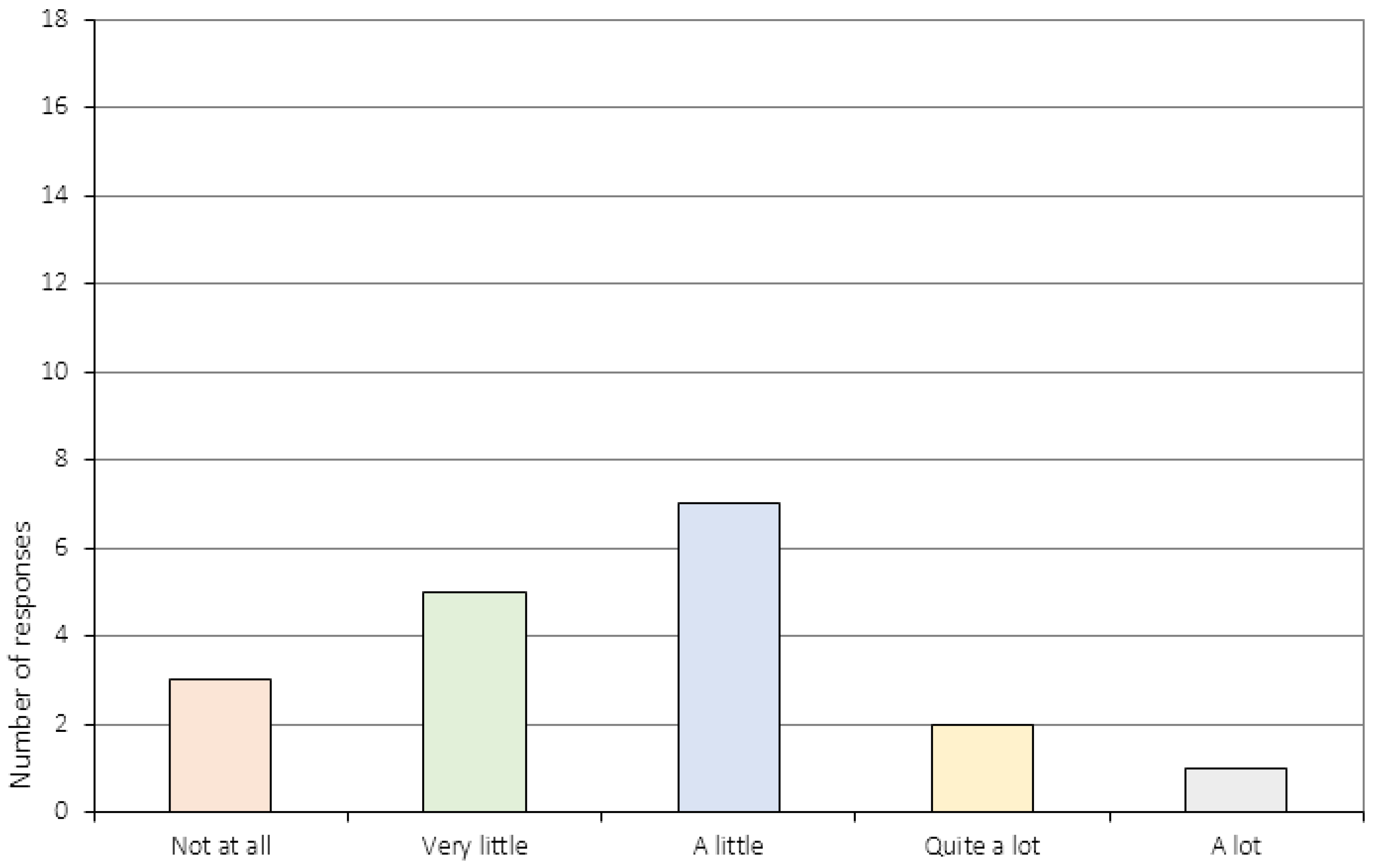

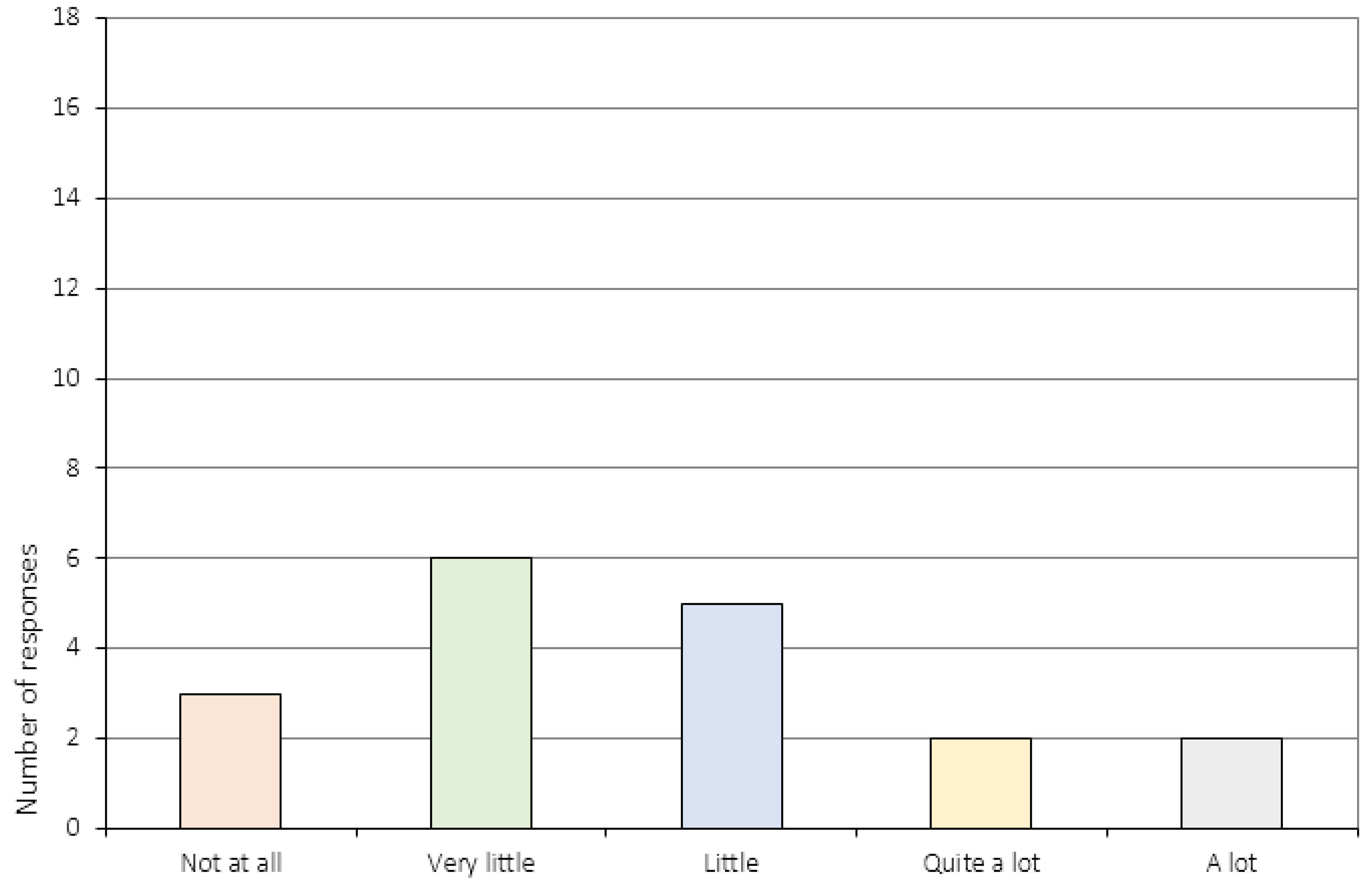

3.2. The Perception of Change

4. Discussion

4.1. Treatment Satisfaction

4.2. Perception of Change

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. General Attitudes towards Treatment (Item 1–5)

Appendix A.2. Treatment Specific Items (Item 7–10)

Appendix A.3. The Perception of Change (Item 6 and 11–16c)

Appendix A.4. The Relationship to the CRT Therapist (Item 17–20)

References

- American Psychological Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stedal, K.; Frampton, I.; Landrø, N.I.; Lask, B. An Examination of the Ravello Profile—A Neuropsychological Test Battery for Anorexia Nervosa. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2012, 20, 175–181. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlgren, C.L.; Lask, B.; Landrø, N.I.; Rø, Ø. Patient and Parental Self-reports of Executive Functioning in a Sample of Young Female Adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa Before and After Cognitive Remediation Therapy. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2014, 22, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perpina, C.; Segura, M.; Sanchez-Reales, S. Cognitive flexibility and decision-making in eating disorders and obesity. Eat Weight Disord. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloi, M.; Rania, M.; Caroleo, M.; Bruni, A.; Cauteruccio, M.A.; De Fazio, P.; Segura-Garcia, C. Decision making, central coherence and set-shifting: a comparison between Binge Eating Disorder, Anorexia Nervosa and Healthy Controls. BMC Psychiatr. 2015, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, K.; Lopez, C.; Stahl, D.; Tchanturia, K.; Treasure, J. Central Coherence in Eating Disorders: A Synthesis of Studies Using the Rey Osterrieth Complex Figure Test. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, K.; Tchanturia, K. A systematic review of central coherence in children and adolescents with anorexia nervosa. J. Child. Adolesc. Behav. 2014, 2, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, H.; Tchanturia, K. Cognitive Remediation Therapy as an Intervention for Acute Anorexia Nervosa: A Case Report. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2005, 13, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlgren, C.; Rø, Ø. A systematic review of cognitive remediation therapy for anorexia nervosa-development, current state and implications for future research and clinical practice. J. Eat. Disord. 2014, 2, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Brockmeyer, T.; Ingenerf, K.; Walther, S.; Wild, B.; Hartmann, M.; Herzog, W.; Bents, H.; Friederich, H.C. Training cognitive flexibility in patients with anorexia nervosa: A pilot randomized controlled trial of cognitive remediation therapy. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2013, 47, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lock, J.; Agras, W.S.; Fitzpatrick, K.K.; Bryson, S.W.; Jo, B.; Tchanturia, K. Is outpatient cognitive remediation therapy feasible to use in randomized clinical trials for anorexia nervosa? Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2013, 46, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brockmeyer, T.; Ingenerf, K.; Walther, S.; Wild, B.; Hartmann, M.; Herzog, W.; Bents, H.; Friederich, H.C. Training cognitive flexibility in patients with anorexia nervosa: A pilot randomized controlled trial of cognitive remediation therapy. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2014, 47, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dingemans, A.E.; Danner, U.N.; Donker, J.M.; aardoom, J.J.; van Meer, F.; Tobias, K.; van Elburg, A.A.; van Furth, E.F. The effectiveness of cognitive remediation therapy in patients with a severe or enduring eating disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Psychother. Psychosom. 2014, 83, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlgren, C.L.; Lask, B.; Landrø, N.I.; Rø, Ø. Developing and evaluating cognitive remediation therapy (CRT) for adolescents with anorexia nervosa: a feasibility study. Clin. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2014, 19, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tchanturia, K.; Lounes, N.; Holttum, S. Cognitive remediation in anorexia nervosa and related conditions: A systematic review. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2014, 22, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Noort, B.M.; Kraus, M.K.A.; Pfeiffer, E.; Lehmkuhl, U.; Kappel, V. Neuropsychological and Behavioural Short-Term Effects of Cognitive Remediation Therapy in Adolescent Anorexia Nervosa: A Pilot Study. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2016, 24, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tchanturia, K.; Davies, H.; Reeder, C.; Wykes, T. Cognitive Remediation Therapy for Anorexia Nervosa. 2010. Available online: www.katetchanturia.com (accessed on 2 March 2017).

- Owen, I.; Lindvall, C.L.; Lask, B. Cognitive Remediation Therapy. In Eating Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence; Lask, B., Bryant-Waugh, R., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 301–318. [Google Scholar]

- Giombini, L.; Moynihan, J.; Turco, M.; Nesbitt, S. Evaluation of individual cognitive remediation therapy (CRT) for the treatment of young people with anorexia nervosa. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giombini, L.; Turton, R.; Turco, M.; Nesbitt, S.; Lask, B. The use of cognitive remediation therapy on a child adolescent eating disorder unit: Patients and therapist perspectives. Clin. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2017, 22, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Noort, B.M.; Pfeiffer, E.; Ehrlich, S.; Lehmkuhl, U.; Kappel, V. Cognitive performance in children with acute early-onset anorexia nervosa. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2016, 25, 1233–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Noort, B.M.; Pfeiffer, E.; Lehmkuhl, U.; Kappel, V. Cognitive Remediation Therapy for Children with Anorexia Nervosa. Z. Kinder. Jugendpsychiatr. Psychother. 2015, 43, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doran, D.; Smith, P. Measuring service quality provision within an eating disorders context. Int. J. Health. Care Qual. Assur. Inc. Leadersh. Health Serv. 2004, 17, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newton, T. Consumer involvement in the appraisal of treatment for people with eating disorders: A neglected area of research? Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2001, 9, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, L. What can we learn from consumer studies and qualitative research in the treatment of eating disorders? Eat. Weight Disord. 2003, 8, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Rie, S.; Noordenbos, G.; Donker, M.; van Furth, E. Evaluating the treatment of eating disorders from the patient's perspective. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2006, 39, 667–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wechsler, D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Third Edition (WAIS-III); Harcourt Assessment: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, D. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI); NCS Pearson Inc.: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, D. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Third Edition (WISC-III); The Psychological Corporation Europe: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn, C.G.; Beglin, S.J. Assessment of Eating Disorders, Interview or Self-Report Questionnaire. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1994, 16, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Brown, G.K. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II; Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Goursuch, R.; Lushene, R. Manual for the State Trait Anxiety Inventory; Consulting Psychologists Press: Mountain View, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlgren, C.L. Cognitive Remediation Therapy for Young Female Adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa—Assessing the Feasibility of a Novel Eating Disorder Intervention; Oslo University Hospital: Oslo, Norway, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lindvall, C.; Owen, I.; Lask, B. The CRT Resource Pack for Children and Adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa; Oslo University Hospital: Ullevål HF, Oslo, Norway, 2010; Available online: http://www.researchgate.com (accessed on 1 April 2016).

- Dahlgren, C.L.; Lask, B.; Landrø, N.I.; Rø, Ø. Neuropsychological functioning in adolescents with anorexia nervosa before and after cognitive remediation therapy: A feasibility trial. Int. J. Eat. Disord 2013, 46, 576–581. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlgren, C.L.; van Noort, B.M.; Lask, B. The Cognitive Remediation Therapy (CRT) Resource Pack for Children and Adolescents with Feeding and Eating Disorders, 2nd ed.; Oslo University Hospital: Oslo, Norway, 2015; Available online: http://www.rasp.no/ (accessed on 1 January 2017).

- Holmboe, O.; Groven, G.; Olsen, R.V. Brukererfaringer med poliklinikker for voksne i det psykiske helsevernet 2007; PasOpp-rapport nr 6-2008 fra Kunnskapssenteret; Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services: Olso, Norway, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lago, C.; Norring, C.; Engström, I. Enkät om behandlingstillfredsställelse: RIKSÄT: Nationellt Kvalitetsregister för Ätstörningsbehandling. Available online: http://kcp.se/kvalitetsregister/riksat/arbetsmaterial-dokument/ (accessed on 15 January 2010).

- Pretorius, N.; Dimmer, M.; Power, E.; Eisler, I.; Simic, M.; Tcanturia, K. Evaluation of a cognitive remediation therapy group for adolescents with anorexia nervosa: Pilot study. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2012, 20, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, L.; Al-Khairulla, H.; Lask, B. Group cognitive remediation therapy for adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2011, 16, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halvorsen, I.; Heyerdahl, S. Treatment perception in adolescent onset anorexia nervosa: Retrospective views of patients and parents. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2007, 40, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roux, H.; Ali, A.; Lambert, S.; Radon, L.; Huas, C.; Curt, F.; Berthoz, S.; Godart, N. Predictive factors of dropout from inpatient treatment for anorexia nervosa. BMC Psychiatr. 2016, 16, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Towell, D.B.; Woodford, S.; Reid, S.; Rooney, B.; Towell, A. Compliance and outcome in treatment-resistant anorexia and bulimia: A retrospective study. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2001, 40, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lask, B.; Roberts, A. Family cognitive remediation therapy for anorexia nervosa. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatr. 2015, 20, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, K.; Treasure, J.; Tchanturia, K. Acceptability and feasibility of self-help Cognitive Remediation Therapy for anorexia nervosa delivered in collaboration with carers: A qualitative preliminary evaluation study. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 225, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graves, T.A.; Tabri, N.; Thompson-Brenner, H.; Franko, D.L.; Eddy, K.T.; Bourion-Bedes, S.; Brown, A.; Constantino, M.J.; Fluckiger, C.; Forsberg, S.; et al. A meta-analysis of the relation between therapeutic alliance and treatment outcome in eating disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 50, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaitsoff, S.; Pullmer, R.; Cyr, M.; Aime, H. The role of the therapeutic alliance in eating disorder treatment outcomes: A systematic review. Eat. Disord. 2015, 23, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulliksen, K.S.; Espeset, E.M.; Nordbø, R.H.; Skårderud, F.; Geller, J.; Holte, A. Preferred therapist characteristics in treatment of anorexia nervosa: The patient’s perspective. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2012, 45, 932–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Easter, A.; Tchanturia, K. Therapists’ experiences of cognitive remediation therapy for anorexia nervosa: Implications for working with adolescents. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatr. 2011, 16, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giombini, L.; Nesbitt, S.; Waples, L.; Finazzi, E.; Easter, A.; Tchanturia, K. Young people’s experience of individual cognitive remediation therapy (CRT) in an inpatient eating disorder service: A qualitative study. Eat. Weight Disord. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, J.; Easter, A.; Tchanturia, K. Service users’ feedback on cognitive training in the treatment of anorexia nervosa: A qualitative study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2008, 41, 542–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strober, M. Personality and symptomatological features in young, nonchronic anorexia nervosa patients. J. Psychosom. Res. 1980, 24, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amianto, F.; Abbate-Daga, G.; Morando, S.; Sobrero, C.; Fassino, S. Personality development characteristics of women with anorexia nervosa, their healthy siblings and healthy controls: What prevents and what relates to psychopathology? Psychiatr. Res. 2011, 187, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| N | Mean (SD) | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 20 | 15.9 (1.6) | 13.1–18.7 |

| BMI Percentile | 20 | 10.2 (17.2) | 0.0–28.0 |

| Duration of illness 1 | 19 | 2.7 (2.1) | 1–7 |

| Global EDE-Q 2 | 20 | 3.4 (1.4) | 0.6–5.4 |

| BDI | 20 | 32.2 (15.1) | 7–58 |

| STAI | 20 | 58.6 (9.7) | 43–78 |

| Item no. | Question |

|---|---|

| 1. | Overall, how satisfied or dissatisfied are you with the course of CRT you have received? 1 |

| 2. | Before you initiated CRT, you were informed about the treatment. Was this information useful? 1 |

| 3. | How did your CRT experiences match the expectations you had prior to treatment initiation? 1 |

| 4. | To what extent did you feel that the CRT sessions were useful to you? 1 |

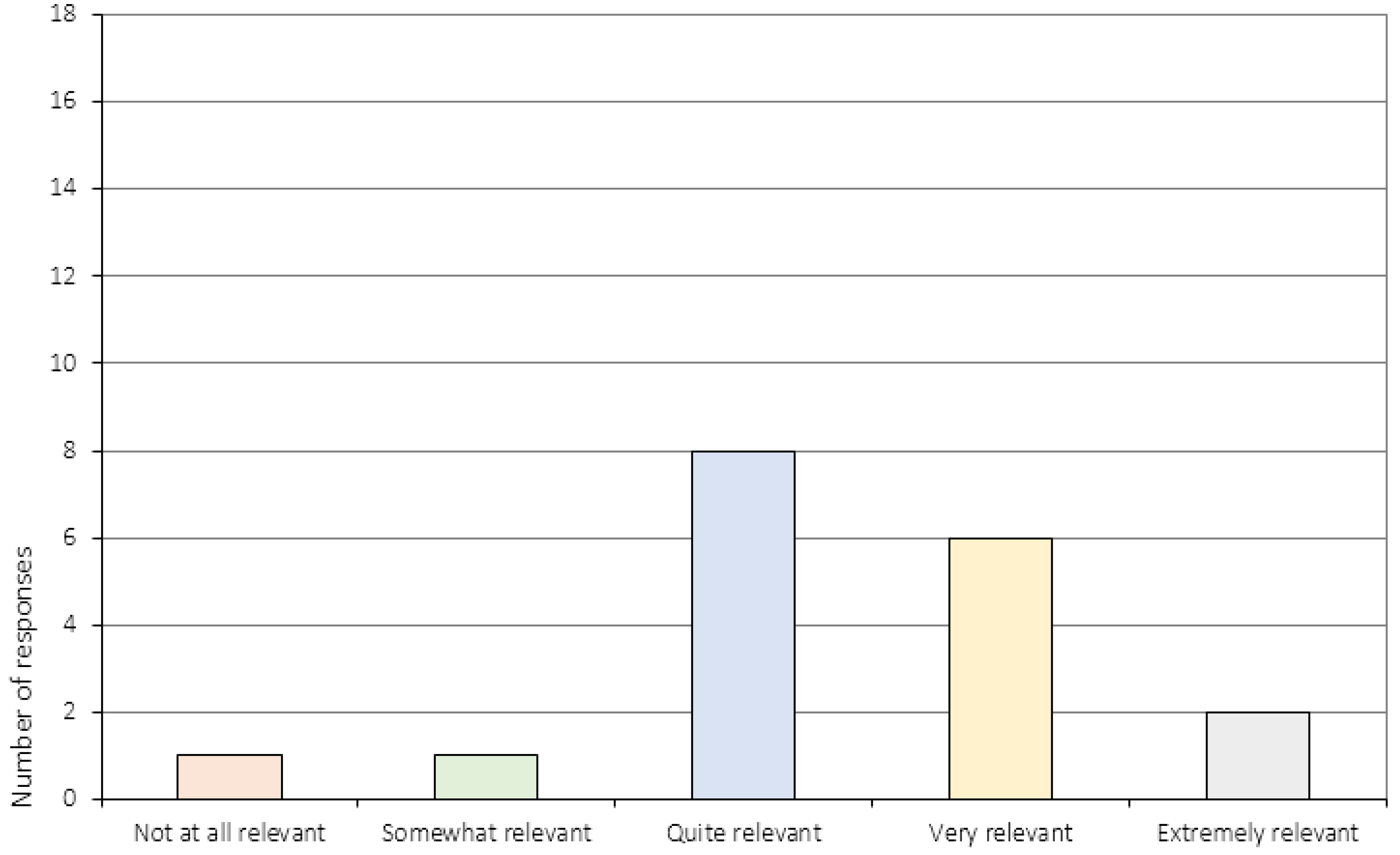

| 5. | Did you experience CRT as being relevant to your situation? 1 |

| 6. | Did you acquire any skills during CRT that might be useful in your everyday life? 3 |

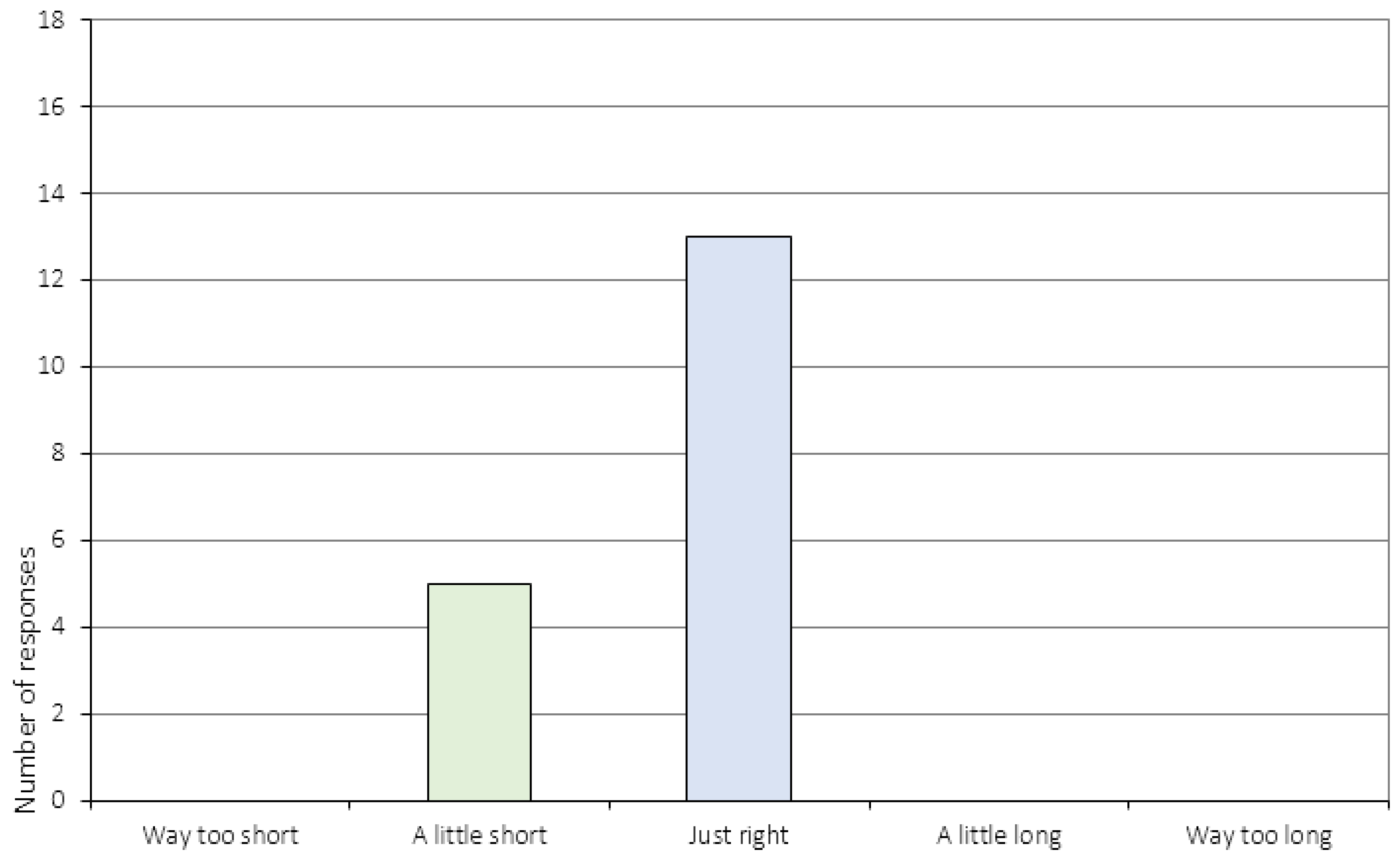

| 7. | How do you feel about the length of the sessions? 2 |

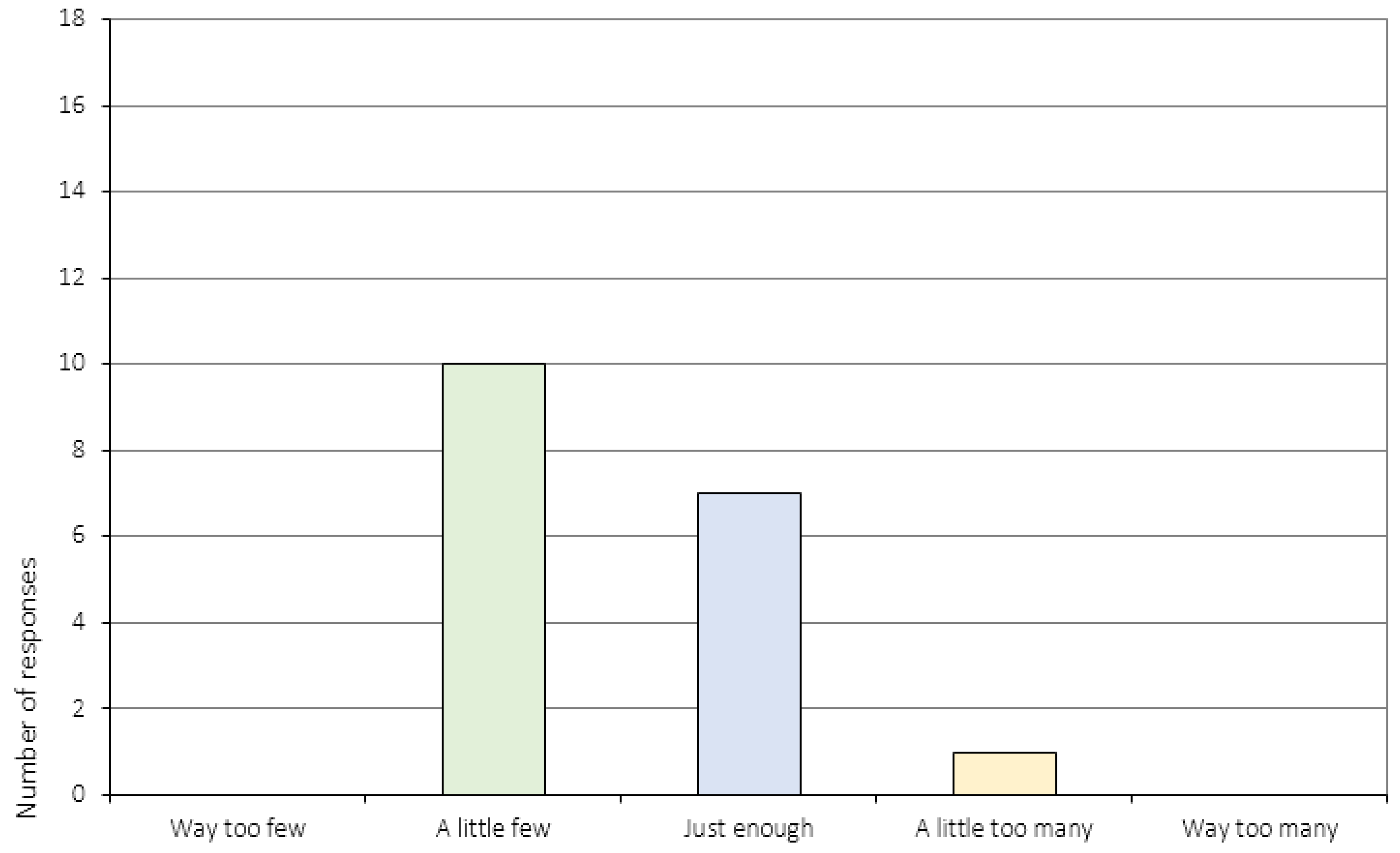

| 8. | How do you feel about the number of sessions? 2 |

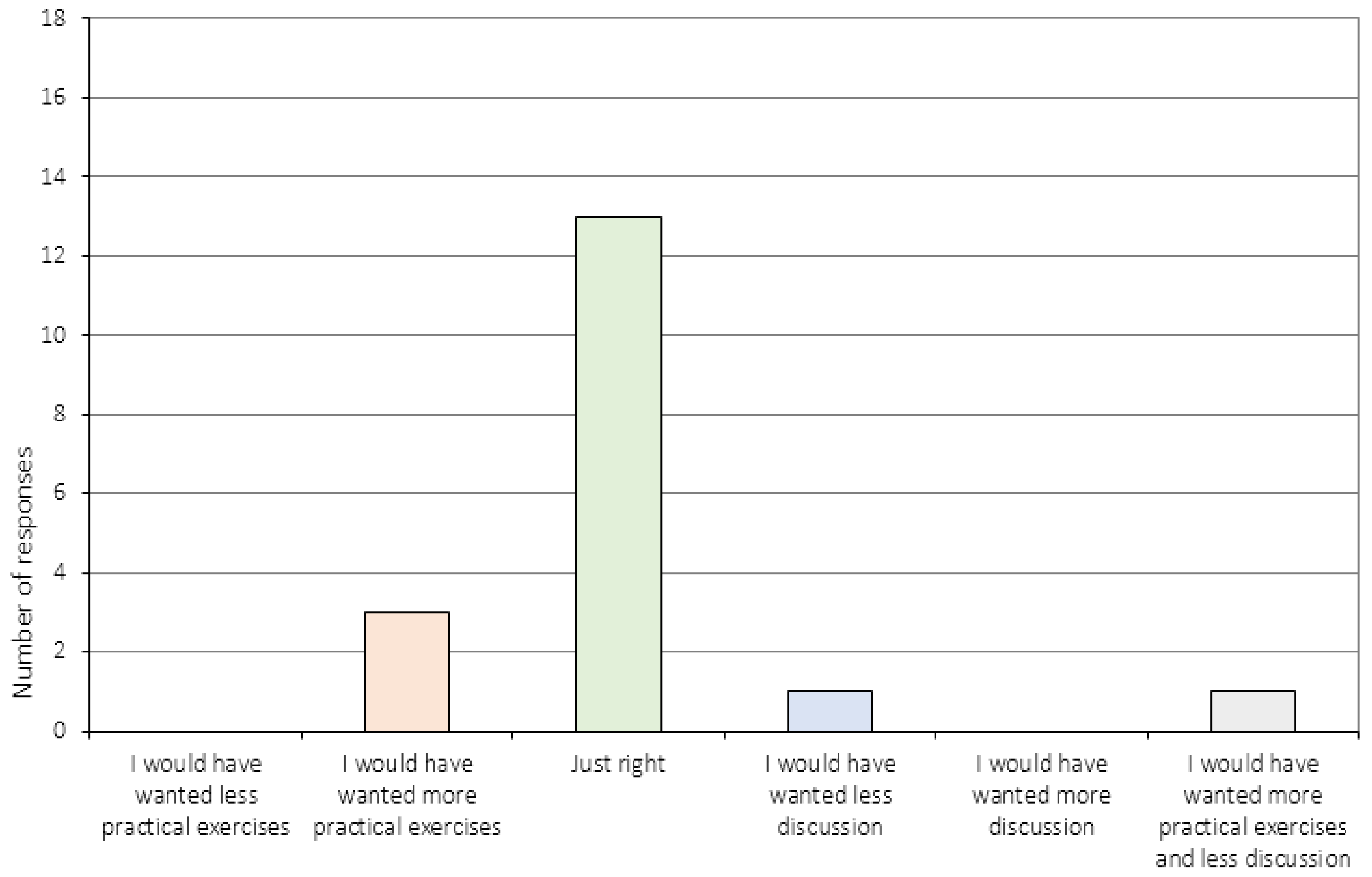

| 9. | How did you experience the division between practical exercises and discussion during the session (you can check as many boxes as you like)? 2 |

| 10. | What is your opinion on the tasks used during the sessions? 2 |

| 11. | How has the way you reflect on your own thinking changed during the course of CRT? 3 |

| 12. | To what extent do you experience distress in relation to your eating disorder now, compared to before you started the CRT treatment program? 3 |

| 13. | Are there other areas in your life which have become more or less difficult now, compared to before you started the CRT program? a) Example no. 1, b) Example no. 2 |

| 14. | What is your relationship to your family like now compared to before you started the CRT program? 3 |

| 15. | How are things working out in your everyday life now, compared to before you entered the CRT treatment program? a) School/work? b) Leisure time/friends? 3 |

| 16. | Do you think the CRT sessions have had an impact on your ability to change with regards to: a) Your eating disorder? b) School/work? c) Leisure time/friends? 3 |

| 17. | How did you experience the collaboration between you and your CRT therapist? 4 |

| 18. | Did you feel that you were treated with respect during the course of CRT? 4 |

| 19. | Did the CRT therapist listen to you? 4 |

| 20. | Did your therapist explain the tasks in a way that was easy to understand? 4 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dahlgren, C.L.; Stedal, K. Cognitive Remediation Therapy for Adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa—Treatment Satisfaction and the Perception of Change. Behav. Sci. 2017, 7, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs7020023

Dahlgren CL, Stedal K. Cognitive Remediation Therapy for Adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa—Treatment Satisfaction and the Perception of Change. Behavioral Sciences. 2017; 7(2):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs7020023

Chicago/Turabian StyleDahlgren, Camilla Lindvall, and Kristin Stedal. 2017. "Cognitive Remediation Therapy for Adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa—Treatment Satisfaction and the Perception of Change" Behavioral Sciences 7, no. 2: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs7020023

APA StyleDahlgren, C. L., & Stedal, K. (2017). Cognitive Remediation Therapy for Adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa—Treatment Satisfaction and the Perception of Change. Behavioral Sciences, 7(2), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs7020023