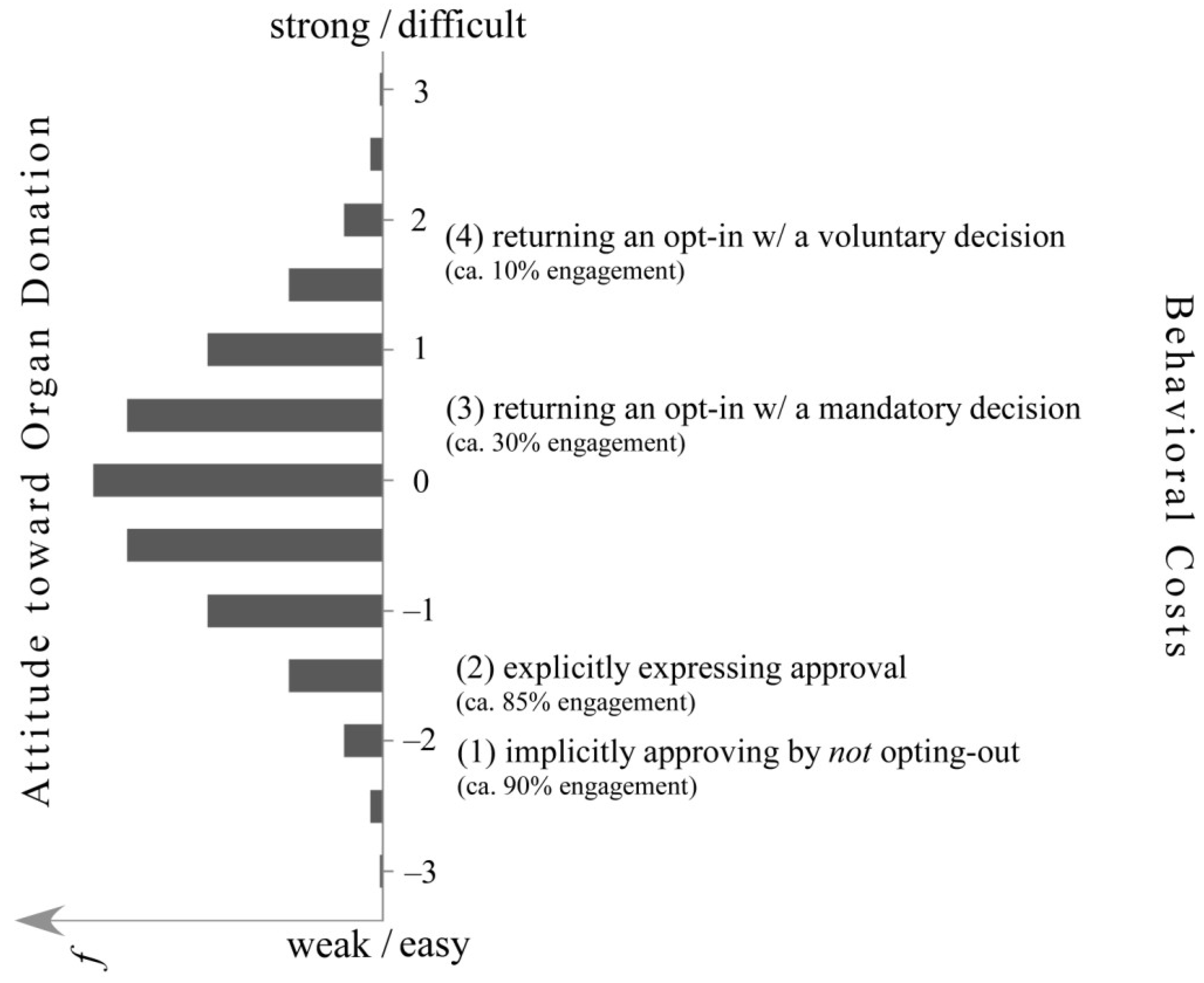

In this view, an individual's attitude represents his or her particular esteem for organ donation (see

Figure 1), and it is equated with the personal engagement likelihoods of the behaviors representing the very attitude [

6]. In other words, the engagement likelihoods of the four specific behaviors depict the typical prevailing attitude toward organ donation in a given society. Hence, these likelihoods indicate that the mean organ donation attitude of people is pronounced enough that about 90% of the population will take no action—not even an action as small as sending back an opt-out card—to avoid being identified as an organ donor, provided that everybody else is assigned as well. However, if this assignment requires active engagement—when the opt-in alternative is applied—the situation changes dramatically. This becomes apparent in the drop to about 10% of the population who agree to be donors. Obviously, people's attitude toward organ donation is, in this example, on average not strong enough to even overcome the apparently marginal costs that accompany an opt-in default.

4.1. Recognizing Effective Costs

The choices to either opt-in or not opt-out apparently do not carry the same actual costs and, thus, do not reflect identical structural forces—although the two behaviors appear quite similar. In their attempt to explain the observed differences in organ donation rates in societies with opt-in as opposed to opt-out defaults, Johnson and Goldstein [

1] also came up with three cost-based explanations: effort, loss aversion or reference dependence, and implied endorsement.

Effort refers to the mental pain that may be involved when a person makes up his or her mind or to the physical labor (i.e., seeking a mailbox) that is required when a person mails a response-card using the postal service. In other words, in their first explanation, Johnson and Goldstein focused on the personal aspects that correspond with structural costs (i.e., environmental demands). These consist of the presumed personal expenditures that are involved when a person switches away from the default, that is, mental and physical effort.

Loss aversion, the second explanation, also refers to behavioral costs. In this explanation, a default and its presumed costs represent the cognitive reference. Any alternative (

i.e., the nondefault) has to be profitable by comparison. In other words, the departure from the benchmark has to promise some benefits or substantively fewer costs than the default; otherwise, people’s aversion to loss—through not gaining anything—results in the persistence of the default [

14].

The implied endorsement, the third explanation, refers to a specific set of behavioral costs. In this explanation, a default represents the normative reference with regard to the expected course of action (e.g., [

15]). Any alternative (the nondefault) implies a departure from the majority position and, thus, the risk of social stigma. According to this perspective, we would expect a person’s attitude toward social conformity—provided such an attitude exists—to fuel the significance of defaults.

If behavioral costs are so crucial, empirically uncovering behavioral costs and detecting potentially behavior-effective boundary conditions becomes indispensable. In line with Johnson and Goldstein [

1], we also suggest systematically comparing engagement likelihoods across different cities, regions, or societies as the measure of choice (see e.g., [

10,

16]). For example, turning off one's car at red traffic lights appeared to be relatively demanding—with a 2% likelihood—in Eindhoven, The Netherlands, compared with two German cities (with a 12–15% likelihood) and Zürich, Switzerland (with a likelihood of 41%; see [

17]). From these numbers and from studying the locations, we learned that one effective nudge in The Netherlands might be to introduce a yellow warning light before traffic lights turn green, which is standard in Germany and Switzerland but was not in The Netherlands at the time of our study. An effective nudge to make people switch off their engines at red lights in Germany might, by contrast, consist of prompts to remind drivers to switch off their engines as found in Switzerland and originally introduced in a massive public campaign.

4.2. Insurmountable Attitudes

Sometimes nudges will not work. Children, for example, could not be nudged into replacing French fries with apples by making fries less and apples more accessible (see [

18]). Increasing the behavioral costs of French fries by making them hard to reach cannot surmount the preexisting food preferences of most children. Likewise, OECD employees opposed decreased temperature defaults of 18 or 17 °C but tolerated defaults of 19 °C in their offices. Apparently, a reduction from 20 to 19 °C does not impinge on the thermal comfort preferences of most employees enough to draw counteraction, but a reduction to 18 or 17 °C, by contrast, makes a majority of employees rebel against the change [

19].

As we presume, the behavior-effective driving forces behind people's behavioral decisions are individual attitudes (e.g., food-, thermal comfort-, or environmental protection preferences). In other words, structural influences, such as nudges, depend on the driving force of supportive attitudes (see

Figure 1) even when the structural influences appear to control behavioral decisions or seem to yield behaviors as incentives or disincentives (see [

2]). In other words, structural measures can aggravate or alleviate behavior as its costs, but they cannot instigate individual performance.

4.3. Offsetting Behavioral Costs with Attitudes

From knowledge of the behavioral costs people endure, we can stochastically (

i.e., for large groups of people, such as societies) derive the specifically required strength of the attitude. Thus, we have to presume that persons who voluntarily opt-in (

i.e., the comparatively most costly behavior #4 in

Figure 1) hold much stronger attitudes toward organ donation than persons who exclusively do not actively opt-out (

i.e., the comparatively cost-free behavior #1). By raising the behavioral costs substantially relative to the not-opt-out condition (#1), about 80% of potential donors would be lost—the ones with a weaker attitude strength than the strength required by the specific behavioral costs involved—with the voluntary opt-in condition (#4). With fewer behavioral costs relative to the voluntary opt-in condition given by a mandatory opt-in decision (#3), only about 60% would be lost. This prediction is based on the fact that the average attitude toward organ donation in most societies is not strong enough to make the majority explicitly donate their organs—on the basis of voluntary or mandatory decisions (see

Figure 1). Thus, to eventually understand the efficacy of nudges, we need to understand the inherent connection between attitudes and costs, that is, the connection between the psychological factor and the structural factor.

According to

Figure 1, neither behavioral costs (

i.e., the structural factor) nor attitudes (

i.e., the psychological factor) can be understood in an absolute sense. They are relative to each other; they are interdependent. Attitudes become manifest in the behavioral obstacles they help people overcome, and conversely, costs become manifest in the strength of the attitude they require to be offset. If organ donation was inherently more important for most, we would find less resistance than the resistance represented by the opt-in conditions, resulting in more donors than only 10%–30%. Thus, with increasing costs, progressively stronger attitudes are required for a behavior to be actualized. Mathematically, the relation between behavioral costs and attitudes can be depicted by the following formula (for more details, see [

7]):

Formula 1 captures the natural logarithm of the ratio of the probability (

pki) that person k will engage in a specific behavior i relative to the probability that person k will not engage in behavior i (1-

pki) as a function of the arithmetic difference between the strength of k’s attitude (θ

k) and the composite of the costs involved in realizing the specific behavior i (δ

i). Note that here, people are distinguishable by the strength of their attitude (left side of

Figure 1)—given the specific costs involved in realizing the attitude-relevant behaviors. Behaviors, by contrast, are distinguishable by how difficult they are to implement (right side of

Figure 1)—given the attitude differences in a certain population. In other words, our conceptual understanding of attitudes fueling behavior in the presence of the obstructive and supportive forces depicted in

Figure 1 represents a

compensatory model of personal and structural forces. Thus, excessive impediments against a particular behavior can and must be compensated for by strong attitudes, whereas weak attitudes can still be overcome with even further reductions in behavioral costs. However and although the Campbell paradigm seems to provide a suitable conceptual framework for understanding the efficacy of structural interventions (e.g., in the form of nudges) and their failures, we have to be aware that the paradigm contradicts the dominant view of

conjunctively effective personal and structural forces in social and much of environmental psychology.

Whereas the Campbell paradigm describes behavioral costs and, thus, structural interventions as generically effective (at least within socio-cultural contexts such as societies; see [

7]), modern-day psychology expects attitudes and costs to interact in a statistical sense when conceptualizing the origins of behavior (e.g., [

20]). In other words, attitudes and costs are thought to moderate each other's behavioral relevance (see e.g., [

21]). The implication of this generally assumed interaction hypothesis is that people are expected to respond rather inconsistently (

i.e., not uniformly) to structural interventions such as nudges or even economic incentives. Effectively controlling behavioral decisions with structural measures, however, requires their effectiveness to be more or less uniform. Thus, the Campbell paradigm would be a promising alternative to the currently dominant conjunctive model of personal and structural forces in social and much of environmental psychology.

Along these lines, Kaiser and Schultz [

21] tested three different conjunctive models previously proposed in the literature. All three speak of a moderating influence of behavioral costs on the environmental attitude-ecological behavior relation: a positive linear model—where the strength of the attitude-behavior relation increases with behavioral costs; a negative monotonic model; and a curvilinear model with a marked drop in the strength of the attitude-behavior relation for easy and difficult behaviors. Contrary to all three models, behavioral engagement turned out to be an unmoderated, thus, unconditional function of environmental attitude (

r = 0.54) in a pooled sample of

N = 3338 participants (as long as the behaviors were not too easy (

i.e.,

p > 0.95) or too difficult (

i.e.,

p < 0.05) and, thus, their distributions remained within technically sensible boundaries for parametric statistics). Kaiser and Schultz’s findings simultaneously challenge the assumption of conditional effectiveness of either attitudes depending on structural forces or of structural forces depending on attitudes. By contrast, however, the conditional effectiveness of structural forces as depending on weak attitudes is commonplace in the literature on nudging (see, e.g., [

1]).

Note that any systematic influence not accounted for by the model—such as moderators, alternative attitudes (e.g., [

15]), or differentially effective behavioral costs—statistically reduces the fit of the model and, thus, eventually falsifies the model. So far, our research on environmental attitudes (

i.e., the attitude toward environmental protection: see e.g., [

8]) has demonstrated that the Campbell paradigm holds true for approximately 95% of the people in a given society in this behavioral domain at least. In other words, anticipating engagement in a specific behavior—on the basis of a compensatory relation between rather uniformly effective behavioral costs and individual attitudes—has turned out to be erroneous in only negligible proportions of individuals.

4.4. Three Examples of the Cost-Attitude Relation

If the Campbell paradigm provides a suitable framework for understanding individual behavior, we should be able to stochastically derive the specifically required strength of the attitude from the behavioral costs that people are willing to overcome. In our own research, we expectedly found that the cost of being a vegetarian—a highly effective, but in most Western societies (with a 5%–10% likelihood), quite a costly way to protect the environment—had to be offset by progressively more favorable attitudes toward protecting the environment. As it turned out, nonvegetarians held significantly weaker environmental-protection attitudes than vegetarians (see [

7]).

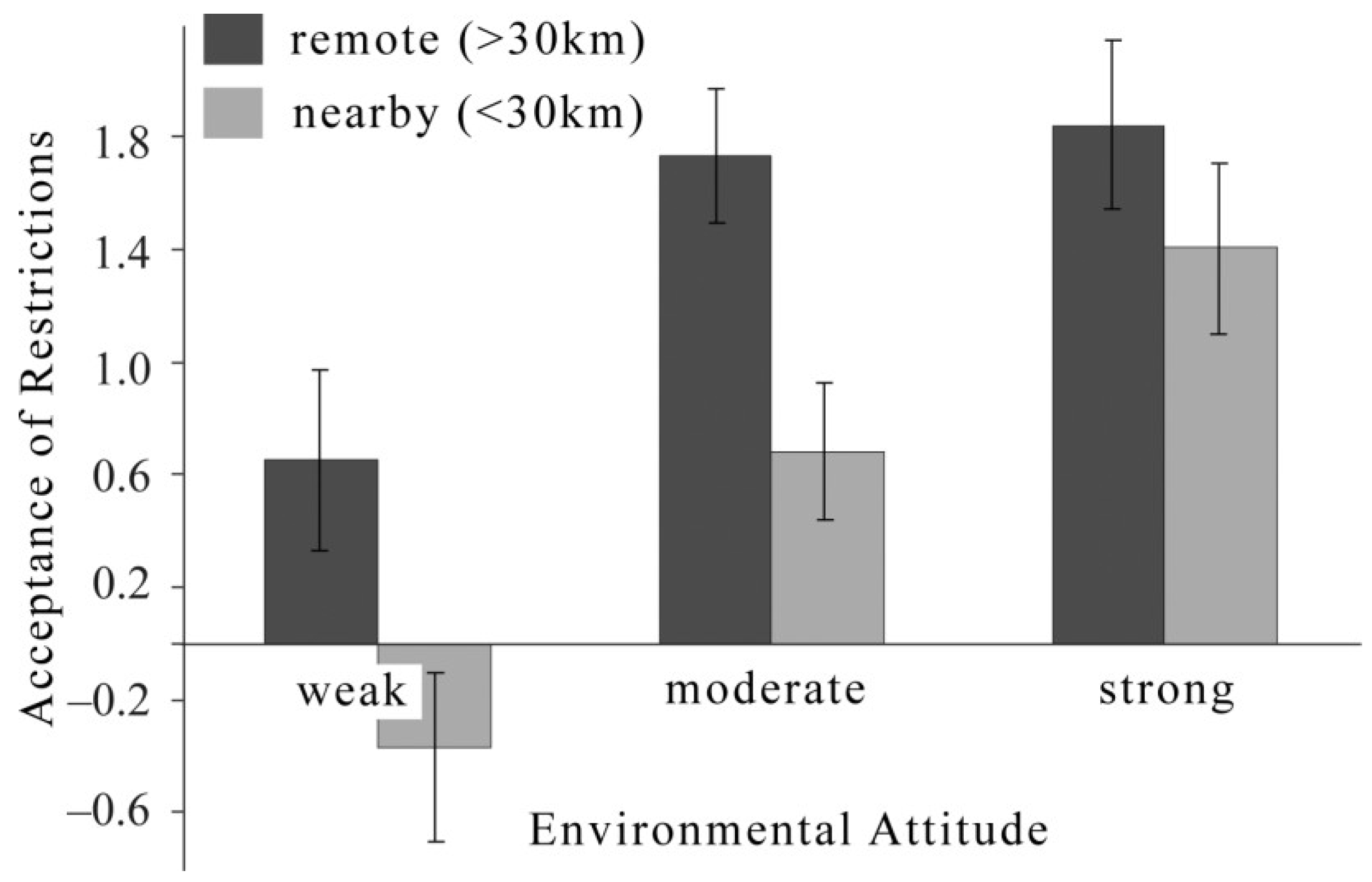

In another study, we explored the NIMBY—not-in-my-backyard—phenomenon (see [

22]). NIMBY indicates that people are better prepared to accept the restrictions and regulations (

i.e., costs) that come with nature preserves the further they live from any preserve. When

not at risk of being affected—by living more than 30 kilometers from any preserve—people generally accept the related restrictions (

i.e., costs) unless they have comparatively weak attitudes toward environmental protection. When at risk of being affected—with increasing behavioral costs—restrictions are accepted with progressively increasing environmental-protection attitudes. Hence, people who are affected by restrictions need rather pronounced environmental-protection attitudes to accept preserve restrictions to an extent that is similar to those of people who are not at risk of being affected (see

Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Remoteness-dependent acceptance of nature-preserve-related restrictions (NIMBY) moderated by people’s attitudes toward environmental protection (i.e., environmental attitude). Vertical bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 2.

Remoteness-dependent acceptance of nature-preserve-related restrictions (NIMBY) moderated by people’s attitudes toward environmental protection (i.e., environmental attitude). Vertical bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Such survey-based examples of the compensatory relation of a person’s attitude strength and the involved behavioral costs were corroborated in still another study that involved overt behavioral engagement in a laboratory experiment [

23]. Claims for an attitude-irrelevant (

i.e., points) compared with an attitude-relevant (

i.e., energy) common resource turned out to be a function of a person’s environmental attitude. Specifically, Kaiser and Byrka [

23] found higher claims for the attitude-irrelevant resource, irrespective of attitude strength (see

Figure 3). Conversely, they also found that persons with strong—as compared with weak—environmental protection attitudes removed relatively less of the common resources.

Figure 3.

Points/kWatt claimed as a function of people’s environmental attitude and of the attitudinal relevance of the common resource. Vertical bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 3.

Points/kWatt claimed as a function of people’s environmental attitude and of the attitudinal relevance of the common resource. Vertical bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.